Early Twenty-First-Century Literary Images from the Margins of the Russian (Orthodox) World

The paper analyzes two artistic artefacts, one graphic reportage and one novel from and about post-Soviet Georgia, focusing on the problem of religious difference within Orthodox Christianity. In imperial history, the fact that Georgia is an Orthodox Christian country was employed by the Russian side to legitimate the Georgian Church’s inclusion into the Russian ecclesiastic hierarchy and, what is more, of Georgia into the Russian empire. Georgian Orthodoxy was thus at least partly and in certain periods denied its religious autonomy. This parallels other strategic renouncements of differences from the Russian side, as for instance in the contemporary usage of the concept “Russian World” that combines the claim of “unity in faith” with language use and cultural consciousness into a mobilizing nationalist trope. The analysis of Viktoria Lomasko’s travel feature about Georgia and of Lasha Bugadze’s documentary novel “A Small Country” shows how contemporary artists and writers reassess the question of Georgia’s religious heritage and its difference from the Russian religious heritage. Whereas Lomasko is critical of the Georgian Church’s moral authority, she also gives ample room for presenting Georgian Orthdoxy’s difference as advantageous with regard to the Russian Church. Bugadze, by contrast, scrutinizes the Georgian Church’s fatal entanglement with the state that engendered both, nationalism and an uncanny allegiance with Russia.

Russia, Georgia Orthodoxy, The Russian World, religious difference, artistic representation, gender

Introduction

Russia has a strained relationship with a number of its neighboring countries, among them Georgia, which was one of the first republics to declare independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.1 Across this historical cleavage both countries are connected by an ambiguous religious commonality, based on their Orthodox Christian faith, that forms the background of both Georgian strivings for independence and Russia’s contestation of its neighbor’s difference, expressing a hegemonic attitude, even legitimizing colonial aggression. This article delves into the contemporary cultural and religious aspect of this complex entanglement as present in two exemplary literary and graphic works, one from Russia, one from Georgia. It analyses how contemporary artists reflect on the Russian-Georgian interdependence in the religious realm and how they critically reassess the nationalist, colonialist and patriarchal constituents of this relationship. Both authors, albeit in different ways, reflect on the entanglement of their respective government and the Orthodox Church.

One of the key questions against the backdrop of which this discussion unfolds is whether Orthodox Christianity is a unity under Russian guidance or a pluralistic union of equal yet diverse churches and believers. It is thus a peculiar case of religious contact that is under scrutiny here: some participants deny the rift altogether. Moreover, both countries’ and their churches’ relations are asymmetrical with regard to power, and yet they share values, ecclesiastical structures and theological dogmata. This situation evolved in a complex imperial context that I will outline at the outset in order to be able to elucidate the many ways in which it still governs modern artistic production.

Religious Differences in a Multiethnic Arena

The Caucasus region is ethnically diverse and has for centuries been at the crossroads of religions, among which Islam and Christianity are the most globally visible. Yet we must be careful not to reduce the interreligious constellation into which Russian-Georgian relations are embedded to a blunt conflict of the Cross and the Half Moon, as the Russian imperial conquerors did (Layton 1994, 194). In the Caucasus, various Christian traditions coexist, the Muslim communities are in part Shiites, in part Sunnites, and the region is home to a once large Sephardic Jewish community. Moreover, the various religious groups‘ sacred spaces overlap and form a palimpsest with “pagan” local cults, producing a hybrid and highly complex spiritual topography (Darieva, Tuite, and Kevin 2018, 1–17). While in the Caucasus, religion has for centuries been a more important identity marker than other components of modern nationality, such as language and culture, certain cultural patterns are shared across religious divides (Manning 2012, 147–49)2. These are often also grounded on or refer to gender roles and therefore, as I will show, have a special significance in the cultural self-reflection of Georgians and other nationalities in the region as well as in their complicated relationship with Russia.

It needs mention, though, that in a longue durée perspective the problem of religious difference or unity between Russia and Georgia became significant only relatively late, with the onset of Russian domination in the eighteenth century, hence “unity in faith,” a concept explained below, resembles a colonialist trope designed to govern loyalties. Importantly, the complex network of other religious and ethnic relations, taken together with the integration into and disintegration from other empires, most importantly the Persian and Ottoman, predated the Russian-Georgian alliance and in many instances complicated it. Starting in the twentieth century, western European and U.S. American players entered the scene, bringing along a Western liberal discourse that too has left its mark on Georgian discussions about religion and gender.

In the post-Soviet Caucasus, cultural processes of appropriation and delimitation—most, but not all of which include a Russian element—are still highly acute. Moscow-centered knowledge systems and their associated regimes of governing differences, also regarding religion, persist and still determine mechanisms of inclusion or exclusion of certain groups from political or ideological communities. If we understand decolonization with Madina Tlostanova (Tlostanova 2012, 133–34) as reflecting and ultimately overcoming (sometimes unconsciously reproduced) colonial or imperial knowledge systems as well as mental and cultural patterns that by means of ontological marginalization govern attitudes towards fellow citizens and neighboring countries, decolonizing Russia clearly is a task yet to be achieved. But my examples from both Russian and Georgian cultural reflection about the religious element in their uneven relationship shed light on an ongoing reconsideration of differences in the Orthodox community that can be considered steps into that direction, even if they are marginal and uncapable of opposing the Russian state’s aggression. The first is the Russian graphic artist Viktoria Lomasko’s travel feature on Georgia that was published in 2016. The other is the 2017 Georgian documentary novel A Small Country by Lasha Bugadze. I will show that Viktoria Lomasko questions the Russian hegemonic understanding of “unity in faith” and eventually deconstructs the associated concept of the “Russian World.” Lasha Bugadze, by contrast, sees not so much “unity in faith” but rather complicity in power. He focuses on the eminent yet problematic significance of the Georgian Orthodox Church in the country’s society and shows its fatal involvement with the (Soviet and later independent Georgian) state that paradoxically results in a situation in which an attack on the (Georgian) Orthodox Church can be perceived as an attack on Russia.

Russia and Georgia—Orthodox Brothers

In the past decades, the Russian Orthodox Church has played an important role in forging a patriarchal state ideology and promoting ethnic nationalism in Russia and beyond, as manifest in its support of the concept of Russkii mir, to be translated as the Russian World or the Russian Peace (Bremer 2015). The contemporary concept of Russkii mir is an adaptation of a nineteenth-century Slavophile ideal: the local self-organization of Russian peasants, called mir or obshchina, that intellectuals like Aleksandr Gertsen considered a Russian indigenous form of socialism and an alternative to Western models of popular sovereignty and democratic representation (Gertsen 1858). Today the term is employed to refer to people who speak Russian and adhere to Russian cultural values (Laruelle 2015; Cheskin and Kachuyevski 2019, 9–10; Caffee 2013, 22–24). It plays a key role in the nationalist legitimation of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, claiming eastern Ukraine as Russian space. But moreover, the Russian World is to a large degree a religious concept, implying a belonging to the Russian Orthodox Church together with the respective Moscow-centered messianistic historical consciousness (Zabirko 2015, 114–16). Orthodoxy, language and historical belonging are presented as constituents of the Russian nation in an emphatic Herderian sense and are importantly not only found within Russia’s confines but also beyond its borders, making Russians “one of the most numerable divided nations on earth”, as leading Russian politicians have it (T.A.S.S. 2019). Russkii mir thus is a concept that negates Russia’s inner multiplicity with regard to language, ethnicity and religion. But it denies difference more generally and also strategically, coupling religious identities with politics, expressing imperialist or at least hegemonic ambitions.

While this concerns a number of former Soviet republics (Ukraine and Belarus, to name but two), Georgia is a particularly interesting case of clashing national and religious group constructions since Georgia clearly does not qualify for membership in the Russian nation with regard to language, culture or historical consciousness. But concerning Orthodoxy, it is affected by the Russian inclusive and homogenizing view on neighboring cultures, the concept employed for this being edinoverie (unity in faith), an emotionally charged Russian term that refers to Christian Orthodoxy, implicitly meaning Russian Orthodoxy, headed by the Russian patriarch. But Georgia, unlike Ukraine, for instance, historically did not belong to the Russian Orthodox Church. Georgia was christianized long before the Eastern Slavs had even ethnically consolidated (in the fourth century AD) (Grdzelidze, George, and Vischer 2006, 20). Moreover, its religious difference is underscored by the fact that Georgia gained its ecclesiastic independence—autocephaly—from the ancient Antiochian patriarchy, not from Constantinople, as Russia did. In the Russian view, Georgian Orthodoxy never enjoyed the prestige of byzantine Greek Orthodoxy because it was the latter that for centuries functioned as Russia’s “mother-church,” the theological and administrative authority for the Russian Church. With the Tractate of Georgievsk (1783) that marked Georgia’s inclusion into the Russian Empire, the Georgian Orthodox Church was successively incorporated into the Russian Synod.3 In this process the ambiguity of the concept edinoverie (unity in faith) is significant. Underlining the meaning of the church Slavonic edinyi as “one and the same” or “one and only,” edinoverie can be interpreted as the identity of Georgian and Russian Orthodoxy. However, the concept also allows for a pluralistic and inclusive understanding (White 2020, 1–22), like the no less contested Russian concept of sobornost’ (collegiality) that locates religious truth in a collective that is not necessarily homogenous.

In spite of the forced Russification (Von Lilienfeld 1993, 222–23) as well as dogmatic and (temporary) ecclesiastic unity, the Georgian Church’s administration and religious traditions deviate from its Russian counterpart. Grdzelidze (2006, 114) stresses the absence of state interference in the Georgian Church, but differences also pertain to cultural forms in religious practice, most importantly the use of the Old Georgian language in liturgy instead of Church Slavonic, and gendered social behavior rules (Grdzelidze, George, and Vischer 2006, 114). Thus, Georgian Orthodoxy compared with Russian Orthodoxy is “almost the same, but not quite,” to quote Homi Bhabha’s (1994, 123) famous phrase. However, this similarity does not bring about aesthetic effects like colonial mimicry, let alone mockery, that would potentially lead to decolonization. The Georgian-Russian religious similarities or affinities that allow for differences are typical for decentralized Orthodox Christianity (Metreveli 2021, 20). They emerged prior to and outside of the imperial encounter, and only later both churches’ unequal interaction became legitimized with “unity in faith” and alleged religious brotherhood (Chkhaidze 2018), while, as Susan Layton has shown, paradoxically the Russian Romantic cultural image of Georgia is one of an oriental, potentially Muslim female (1994, 191–211).

The Russian policy of claiming the Georgians’ faith to be identical and thus fully absorbable into Russian Orthodoxy was neither uninterrupted nor consistent. The Soviet Union was militantly atheist. Since the outbreak of World War II, and most palpably with Brezhnev’s stagnation, however, the Soviet authorities showed a certain tolerance towards religion, including the Georgian Church as spiritual backbone (Grdzelidze, George, and Vischer 2006, 220–21). Religion was reinterpreted as national tradition or folklore and politically approved as morally uplifting (Dragadze 1988, 73), typically practiced by elderly females in the private sphere (Gurchiani 2021, 105). But this was also true for Russia and other parts of the Soviet Union, and can be explained with the social position of aged women in the USSR who became virtuosos in the spiritual realm (Gurchiani 2021, 102) while their belief could conveniently be taken as a remnant from the past. Regarding popular religiosity, tolerance in Georgia was more pronounced than in Russia—in this case, the USSR’s center-periphery relations brought about weaker pressure at the fringes, which among other factors can be explained with the established Soviet regime of governing nationalities. Even though the Bolsheviks’ utopian aim was a classless, atheist, internationalist society, they considered national consolidation an indispensable if evil step on the path to communism and therefore tolerated certain expressions of nationality. Among them could be elements taken from religious culture, sublimated as expressions of popular spirit (Slezkine 1994, 424, 429). Thus the religious heritage withstood the socialist period and was charged with a conservative dissident tinge that attracted certain factions of the elites.

As a result, after the collapse of the USSR, the Orthodox Church became a powerful actor, successfully claiming to be the core and defender of the Georgian nation (Zviadadze 2021, 211–13), as post-Soviet Georgia suffered from deep economic crisis and several separatist wars as well as territorial losses, induced by Russia. In the social arena, however, both Churches, the Russian and Georgian, opposed emancipation, the right of abortion, non-heterosexual relations and other liberal political pursuits side by side. Particularly since the breaking off of diplomatic relations in 2008, both Churches try to mitigate their countries’ political confrontations (Ifact 2020).

Viktoria Lomasko’s Georgian Travel Feature

Viktoria Lomasko is a prominent graphic artist. She started her career with graphic reportages (graficheskii reportazh), a genre which combines journalism with spontaneous, documentary drawings and is akin to documentary comics. Viktoria Lomasko’s work of the 2000s was an integral part of the Russian artistic movement of social graphics (sotsial’naia grafika). Her specific genre evolved from her graphic documentation of court hearings in the trial against the curators of the 2004 art exhibition entitled “Watch Out: Religion!” (Осторожно, религия!). Christian Orthodox activists had violently attacked the exhibition for its alleged blasphemy and engendered one of the first religiously motivated trials in post-Soviet Russia, holding the liberal organizers of the exhibition responsible for hurting their religious feelings.4 In court, photography and video-taping, perceived by many as media more suitable for objectively capturing reality, are prohibited, hence Viktoria Lomasko documented the trial hearings with her drawings, for which she was first welcomed and later harassed by Orthodox activists (Deutsche Welle 2013)5. Thus, right from the start, Lomasko dedicated her work to reflecting about the antiliberal turn Russian politics have taken since the early 2000s. Many of her drawings contain speech balloons and resemble comics. But she only occasionally arranges the pictures in sequences of frames, as comic authors usually do. The graphic elements in Lomasko’s works are more often accompanied by captions and journalistic or documentary text, written after direct observation and sometimes interviews. Thus, Lomasko’s graphic reportage complements the mass media’s (missing or manipulative) coverage of politically controversial events with hand-made, openly subjective drawings that are embedded in a recognizable setting and give the graphic artist the authority of a witness. When presenting her work, Lomasko explains her peculiar artistic form as a continuation of early Soviet reportage.6 But her work also resonates with contemporary Western, particularly U.S. American documentaries and journalistic pieces in graphic form, which Rocco Versaci (Versaci 2008, 109–38) terms comic reportages and which he links to the by the early 2000s exhausted genre of new journalism that has metamorphosed into an artistically more credible, more individual form, “anti-‘official’ and anti-corporate” (Versaci 2008, 111). While graphic reportage gains its credibility by stressing its subjectivity (Versaci 2008, 116) and marginal status, its ostensibly hand-made outlook seemingly contradicts the means of its distribution: Viktoria Lomasko’s work is brought to the audience via electronic media, mostly the internet and social media. Only in the West are Viktoria Lomasko’s works palpably present beyond the electronic sphere: collected in printed book editions (2017 Other Russias, 2019 in German Die Unsichtbaren und die Zornigen and French D’autres Russies) and numerous exhibitions, for instance in Bochum, Manchester, London and Bale. She has frequently received fellowships as artist in residence and other honors.

Viktoria Lomasko has repeatedly traveled to former Soviet republics, among them Georgia. During these journeys she was usually hosted by activists who organized creative workshops with Lomasko about the emancipation of women and minority rights issues. Afterwards, Viktoria Lomasko produced graphic features of these trips. Her Georgia feature is available online on colta.ru, where it was published in 2016.7

Viktoria Lomasko is highly aware of the various traditions that inform her perception and representation of society. While, as mentioned above, she is artistically indebted to Soviet documentary drawing, she is one of the few Russian artists who publicly address the deeply rooted imperialism and racism in Russian society that permeates Russian images of Asian Soviet republics and other peripheries of the Soviet realm.8 With her reductionist drawing style and selection of motifs, she displays critical distance to colonial iconographic traditions and reflects on Soviet education and social practice with this regard: “It seems to me that already in Soviet times people felt an unspoken hierarchy. The Russians were the titular nation. Belarusians and Ukrainians – their younger brothers. Then the Caucasian peoples. They are not Slavic, they are more remote, but they have an ancient culture, the sun, the sea and delicious food. And finally, the peoples of Central Asia, whose territory was violently included in colonial wars and divided into republics quite arbitrarily in Soviet times.”9 While Viktoria Lomasko ironically states that she is the last Soviet artist (Youtube 2020) (even though she was only 13 years old when the USSR dissolved), it is interesting to delve more deeply into how she critically reassesses the Soviet legacy and its persistence in post-Soviet Russia.

The Georgian Orthodox Church

Viktoria Lomasko’s critical view of Russia’s relationship with the former Soviet republics is also reflected in her Georgian travel feature, in which she devotes a significant amount of attention to issues connected with religion, religious practice, gender, sexual orientation and culture. In this respect the Georgia feature is typical of her travel writing, in which the religiously legitimated social oppression of women is always a topic of paramount significance. Lomasko writes and draws about female circumcision, polygamy, abortion, virginity, domestic violence as well as underage forced marriages.

In her text about Georgia, she describes the generally strong presence of the Orthodox Church in Georgian society and repeatedly mentions its active role in the enforcement of a conservative worldview with traditional family values and patriarchal gender roles,10 her focus being on those people who in her view suffer from the enforced Christian order of things, mainly women and people who conform to the heterosexual norm. In her workshops with Georgian women, Lomasko felt the urgency to address the social control over females exerted by the family and the Church, stressing that women are dispossessed of their bodies in the name of Christianity. She describes in detail how homosexuals and LGBTQ activists are harassed by Orthodox clergy and believers who do not shy away from physical abuse, be it on the occasion of demonstrations (2013) or in everyday life. Lomasko moreover reports about the activists’ critique of restrictions of free speech and the freedom of the arts on the grounds of religious arguments, which connects well to her own previous work on the “Watch Out, Religion!” case, in which the freedom of the arts (artists and curators) was eventually subordinated to the protection of religious feelings and “honor.”11 Lomasko in this passage compares the Georgian and the Russian legislation about hate speech and blasphemy, pointing out the absence of respective laws in Georgia—a result of the Western liberal influence on the constitution. This is tantamount to a preference for liberty and rebuff for the protection of moral values in Georgia, yet the incidents of aggression against women and sexual minorities point in another direction, one that resembles the Russian Orthodox rather intolerant stance. The latter is shared by the Georgian Orthodox Church that—unsuccessfully—opposed the passing of an antidiscrimination law for Georgia that included sexual orientation as prohibited ground of discrimination.12

From these descriptions we can infer that Viktoria Lomasko speaks from a Western liberal perspective, in which men and women have equal rights, the individual should have full control over his/her body and sexual minorities should not be discriminated against. However, against the backdrop of Soviet atheism and leftist progressive convictions, it deserves mention that Lomasko’s feminist emancipatory verve has deep roots in socialism and, until well into the 1930s, was a cornerstone of Soviet anti-religious social politics, brutally implemented in allegedly backward regions such as the Caucasus and Central Asia. Lomasko explicitly places herself in that tradition. This became obvious in a comment to an exhibition in 2017 when she affirmatively referred to the sentence that in today’s patriarchic post-Soviet countries the most progressive family members were the grandmothers (Lomasko 2016, 35). Non-heterosexual desire, by contrast, was taboo in Soviet times, at best denied or ignored but also often attempted to be “cured” by means of psychiatric treatment. With their homophobic tendencies, hence, the Russian and Georgian Orthodox Churches connect well with Soviet discrimination policies.

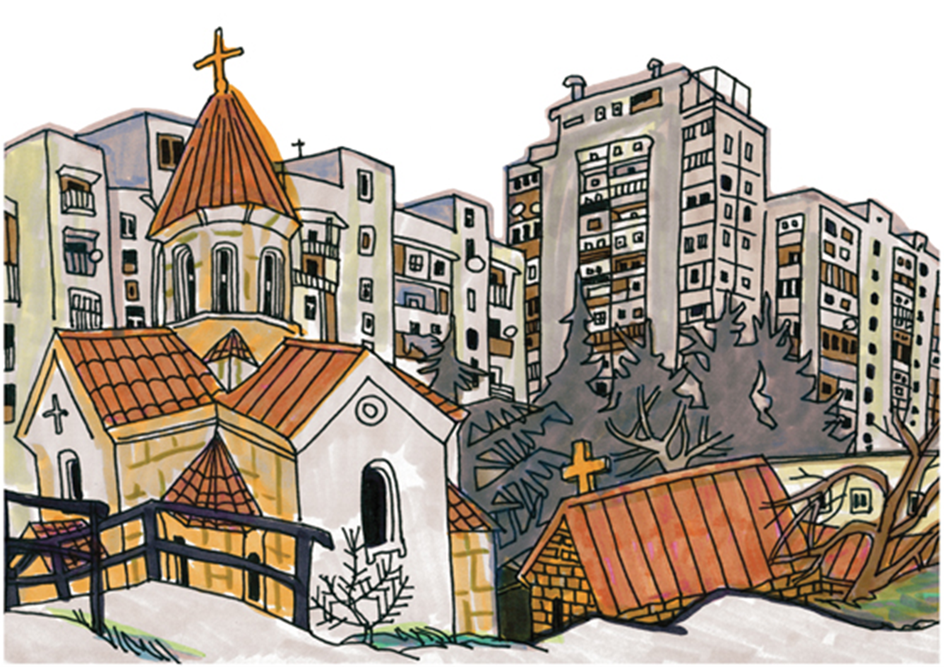

Another of Lomasko’s observations refers to the Georgian Orthodox Church’s massive building of new places of worship in the capital Tbilisi.

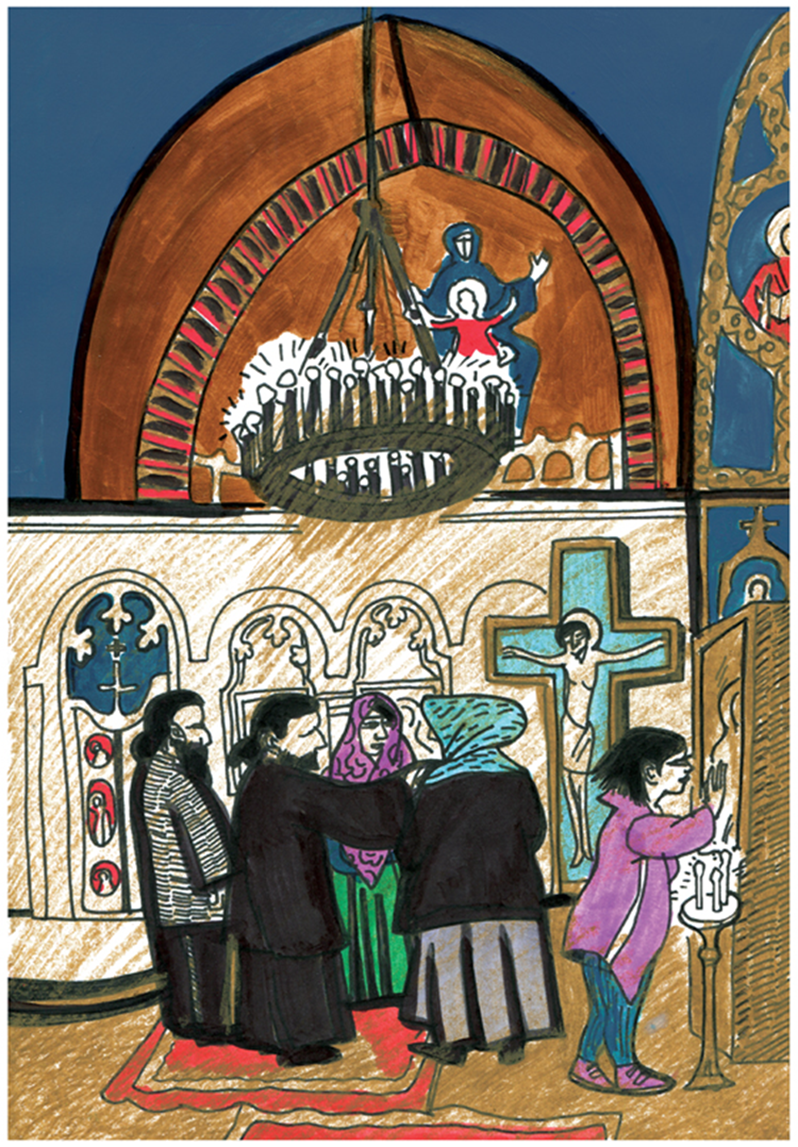

Lomasko includes one drawing in which she poignantly juxtaposes the architectural style of high-rising Soviet apartment blocks with the traditional sacral architectural style that is predominantly used for new churches. In the accompanying text she stresses the space consumed by the new constructions that arise on former playgrounds and other public spaces, thus threatening the city’s already delicate social equilibrium. But most striking are Lomasko’s thoughts about religion and politics in Georgia, particularly the Church’s place in society, which she observes through the Russian prism. The Georgian Orthodox church, she claims, is more remote from the state than the Russian Orthodox Church, which for her is undoubtedly positive. She also appreciates its loser attitude in customs that express hierarchies by means of regulating the believers’ behavior in the church: In contrast to Russia, in Georgia the members of the parish are allowed to sit down during worship and women may attend service in pants and without scarves, both unthinkable in a contemporary Russian Orthodox service. A less hierarchical relationship is also detectable among priests and their parishes. Lomasko finds Georgian clergy to be more easily approachable and expresses this in a separate drawing of a priest standing close to two women with bare heads, wearing trousers.

According to the information that Lomasko provides about her working process, she was allowed to draw inside the church, which she did not expect against the backdrop of her Russian experience, but she does not delve into possible reasons for this treatment, potentially her privileged status as a Russian Orthodox sister-in-faith and artist. Generally speaking, Lomasko acknowledges differences and prefers Georgian Orthodoxy to its Russian counterpart. In this valuation Viktoria Lomasko can be considered a typical post-Soviet Russian intellectual. She embraces the Soviet era’s progressive feminism and combines it with a liberal attitude in questions of sexual orientation. However, she prefers Georgian Orthodoxy to Russian Orthodoxy mainly because it is less palpable. Overall, she is critical of the rise of the Georgian Church and its alliance with nationalism, which in Lomasko’s case is due to her sympathy with marginalized women and LGBTQ people, even though ironically her stance resonates with the imperial and Soviet Russian view of the Georgian Church as cradle of nationalism.13

Georgians – Armenians – Azerbaijanis

Another important topic of Lomasko’s feature is her reassessment of religious differences and nationalities in Tbilisi. She juxtaposes Armenians and Georgians, both predominantly Christian nations that draw on their ancient Christian traditions in constructing their identities. But whereas Russian and Georgian Orthodoxy belong to the Byzantine Greek tradition, the Armenian Apostolic Church has a separate tradition and was historically more loosely connected with Byzantium.

Lomasko reports the family history of the Armenian Yana, whose family has lived in Tbilisi for four generations, representing the once large, even dominant ethnic group in the Georgian capital that has diminished significantly since the collapse of the USSR. Yana is nostalgic about the pre-1990s insignificance of national belonging in Tbilisi’s social life. Lomasko quotes Georgians who dislike Armenians for their involvement in business and commerce, but also because they feel historically dispossessed of their own country by Armenians, whose presence beyond Armenia’s confines they interpret as illegitimate dwelling on “foreign soil.” The quest for a monoethnic populace, in turn, is a relic of the Soviet past. As mentioned above, the Soviet nationality policy took nationalism as a given and strove to create Soviet republics with respective autonomous subdivisions that would be linguistically, ethnically and culturally homogenous—a mission impossible, not least in view of the often dominant religious self-identification that was not at ease with secular Soviet categories. The by now 100 year-old demarcations provoke wars until the present day (e.g. the autumn 2020 and 2022 wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan).

Lomasko writes and draws elaborately about Armenian, Georgian and Muslim Azerbaijani inhabitants of Tbilisi and their complicated relations. She closely describes Seimur Baidzhan, a writer from Azerbaijan who in his novel Gugark talks about the beginning of the Azerbaijanian-Armenian war around 1990. But she also quotes his descriptions of the widespread domestic violence among Azeris, not all of whom are foreign citizens, since Georgia is home to a significant Azeri minority. Through Seimur Baidzhan’s mediation, Lomasko got in contact with other exile intellectuals from Azerbaijan. She quotes the blogger Günel Mövlud, who critically writes about the situation of women in the Southern Caucasus, stressing the difficult situation of Azeri women in Georgia caused by patriarchal family structures that lead to violence, a lack of education for girls, arranged underage marriages and social isolation. Here Viktoria Lomasko puts forth a generalizing thesis about gender and morality in Caucasian societies. Rather than diverse religions, she asserts, a shared local culture is paramount for morality, which she shows in the notion of namus / namusi (honor and chastity).

“In the Caucasus there is an expression that signifies the right conduct of a person in society. In the Azerbaijani and Armenian language namus, in Georgian namusi. For men, namus means honor, conscience. For women, namus refers exclusively to sexual behavior, to their unattainability.”14

Consequently, Lomasko considers the three south Caucasian societies to be similar in their normative gender models and ideas of respectability, their dominant religious self-description as Muslim or Christian and their innate hatred notwithstanding. She thus on the one hand extrapolates the Soviet era’s transformations of religious customs into the national tradition (Gurchiani 2021, 108), while on the other hand questioning the religion-culture-nexus that reemerged—not least due to the Soviet nationality policy and widespread stereotypes about natsional’nyi kharakter—in the relationship of post-Soviet national groups. Subsequently, Lomasko quotes Seimur Baidzhan with the observation that the rigid norms of namus are tied to social status—for the poor, namus is to be achieved exclusively by means of social conduct, whereas particularly women from the economic elites can allow themselves to disregard namus rules without consequences. The Russian graphic artist gives examples for how namus is enforced by males and how their actions depend on their own and the woman’s socio-economic status. But Lomasko also reports about a countermovement against namus that she clearly sympathizes with. Young activists, organized in an ethnically mixed group of “Caucasians” from Georgia and Azerbaijan, resist social pressure and offer lectures for their peers that are intended to educate “thinking citizens”. In her discussion of namus, Lomasko takes a position that is rooted in enlightenment discourse, and here again traces of the Soviet heritage can be felt as she provides a Marxist interpretation of religious norms as “super structure” that reflect economic power relations and presents the activists’ circle as a transnational progressive initiative, united in a struggle against irrational forces that limit the female’s freedom and individual self-expression. In this context it should be mentioned that not only is namus a concept shared in larger parts of the Caucasus, but also that the kidnapping of young women for marriage would be a case in point that however remains beyond the travelogue’s scope (Grant 2009, 77–82).

In a comparative view of other former Soviet republics, though, revivals of gendered constraints based on religious culture can be observed as well. One illustrative example is the discussion of uyat (female shame) in contemporary Kazakh society. As Kudaibergenova (2019, 363–80) shows in her study of female bloggers opposing male attacks on their alleged shamelessness in Kazakhstan, some males seek to restrict women’s rights of self-determination. Kudaibergenova, however, draws a different picture of the ways in which the neo-religious cultural pressure is countered: her female protagonists act out as individuals with a credible, since electronically documented personal story and employ cross-medial strategies to claim their freedom. These women operate on a performative level in social media rather than by means of real-life rational discussion, as the group Lomasko describes seems to do.

From these descriptions of Lomasko’s travel feature it becomes clear that she can indeed be located in an established perceptional scheme — that of the Russian intellectual who travels to the imperial lands and appropriates them for his/her culture. Russian and Soviet knowledge production about the Caucasus provide an elaborate set of ideological tropes expressed in literary and iconographic traditions (Layton 1994; Maisuradze and Thun-Hohenstein 2015; Chkhaidze 2018). Lomasko strives to avoid these schemes, their imperial connotations and implicit hierarchies, displaying genuine interest for Georgia as a different country, especially in terms of religion. What remains from the Russian and Soviet intellectual tradition, though, are indiscriminate attributions such as “Caucasian cultures” towards which the intellectual takes a progressive stance, the wish to overcome “outdated” religious and social structures and to achieve equality. In post-soviet decolonial studies, similar positions have raised sharp criticism. In particular, the universalist heritage of the Enlightenment that makes us assume, for instance, that a modern and civilized society can only be secular was criticized as once more projecting specific western norms onto non-western societies. As Vika Kravtsova has shown, in the post-Soviet realm this pattern is particularly pertinent with regard to feminism, when Russian feminists speak out for Central Asian women, for instance (Kravtsova 2019). One may wonder, though, whether there would at all be a way in which a Russian female activist could display interest in other post-Soviet societies without tapping into the (post)colonial pitfall. Lomasko deserves credit for searching for new, less binary approaches to describing the Caucasus and, what is more, for critically reflecting on Russia’s colonial heritage, although in her graphic travelogue about Georgia, Russia is present rather implicitly by means of topics that are relevant for both societies. Regarding religion, Georgia and Russia appear similar in terms of the Church’s intolerance of sexual minorities as well as promotion of popular conservatism along with its impact on women and their bodies. But at the same time, Lomasko accepts the Georgian Orthodoxy and in fact presents it positively as culturally different.

How does this resonate with “unity in faith” (edinoverie) and the concept of the Russian World (Russkii mir)? A more recent exhibition (opened in May 2019 in London) of Viktoria Lomasko contained a composition that she herself called Russkii mir and that she described with the following words:

Against the backdrop of ancient ruins, in the midst of weeds there are communists, prerevolutionary characters, a girl with a flag, symbolizing new patriotic sentiments, and also the figures of my parents. Daddy is holding his painting “The Clownade” in his hands that is critical of Putin’s regime and that he carries to a demonstration in Serpukhov. The ruins of a church and the weeds represent the abandonment of contemporary Russia.15

For Lomasko, the Russian World refers to Russia’s inner condition and is associated with abandonment. The contrast to the officially hailed Russian World could not be bigger. The idea of community is absent, the Church—symbol of Orthodoxy—is destroyed, but more strikingly a leader or landlord is missing—which is expressed in the Russian word bezkhoznost’, abandonment, literally “lordlessness.” As becomes clear from this quotation, Lomasko’s cautious praise of Georgian Orthodoxy as different from Russian Orthodoxy is a strategic statement showing that the way out of Russia’s crisis would encompass the recognition of plurality and difference within and outside of its own territory.

Lasha Bugadze’s First Russian

Who would a contemporary Georgian writer, born 1977, call the “first Russian”?16 It is the medieval historical figure of Iuri Bogoliubskii, a nobleman from Novgorod that married the Georgian queen-to-be Tamar. As Bugadze asserts, “after two years he was kicked out of Georgia and thereupon invaded the country twice to win back the throne and his wife” (Bugadze 2018, 264). In the course of the centuries, this medieval historical event gained iconic status for the political liaison between Russia and Georgia. Bugadze’s fictional prince Bogoliubskii, however, turns out to be impotent when with his wife but does have sex with animals. In Bugadze’s version of the story, this is the reason why Queen Tamar has their marriage invalidated. Thus, in his novella of 2002, Lasha Bugadze transforms the dynastic episode into a political satire, even travesty, while deconstructing the common principle of chronological presentation in historiography. The narrator comments, “The allegory is obvious: the first Russian and Georgia’s first disappointment, the first abuse, the first cruelty, the beginning of Georgian collaborationism” (Bugadze 2018, 453).

Lasha Bugadze’s version of Tamar’s story clearly is a post-imperial phenomenon, as it re-arranges discursive material from the period of subjugation. The motif of Georgia or the Caucasus as a sexually desired and subdued female and the Russian as her male conqueror has been firmly rooted in Russian culture since the early nineteenth century (Layton 1994; Sahni 1997). The tale has affected Georgian models of self-description well into the late twentieth century by means of the Russian-centered Soviet educational system. Bugadze transforms this material in such a way that he presents Tamar’s and Iurii’s marriage as an outcome of the bride and bridegroom’s surrounding’s strategic rationale. The Georgian nobility supports Iurii as prospective spouse even though they know he is an inadequate choice, and thus Tamar’s Georgian fellow countrymen, by playing the Russian card, betray their queen. As the above-quoted passage shows, this is presented as the Georgian elite’s “primordial sin,” a blueprint for the later entanglement of Russians and Georgians. On behalf of Bugadze this interpretation of history is in many respects provocative, first and foremost with regard to gendered national discourse. In Georgia, Tamar is considered a strong woman; she was canonized as a saint. Along with Saint Nino, who baptized Georgia, she is the only female figure that acquired a place in the thoroughly masculine popular historical and religious consciousness. Both women are figures from the remote past, hence attributes ascribed to them are archaic and idealized and mirror traditional expectations towards female Christian behavior that in turn exert influence on conceptualizations of a Georgian woman’s alleged nature. All the more remarkably, though, Bugadze’s Tamar does not comply with idealized Georgian womanhood, for which purity and unlimited motherly dedication are paramount. His Tamar has desires of her own and she disentangles herself from the wishes and dynastic considerations of her surroundings. But most importantly Bugadze presents Tamar as a physical creature with a female body, which is unheard of when addressing a Saint, whose body is by definition the site of transcendental processes. This violation enraged Georgian society even beyond the reading audience when the text was published in a journal in 2002. Bugadze was accused of blasphemy and the desecration of a national saint.

The scandal around this text in turn became the subject of Bugadze’s 2017 documentary novel A Small Country. The narrator and protagonist of this novel is an author, a character that shares many traits with Lasha Bugadze. Having published his Tamar travesty and received death threats on its grounds, he recounts the way in which the national media, friends and family all become involved in the affair that for him lays bare the interaction of religion and politics in a small country. In the course of the turbulent events, the author comes into contact with the highest representatives of state, Eduard Shevardnadze, former Soviet Secretary of State and then president of Georgia, and Ilia II., the patriarch of the Georgian Orthodox Church, who urges him to recant, promising him under that condition that he would be granted forgiveness.

A Small Country shows Georgia in the process of reconstructing a Christian Orthodox religious identity after decades of decreed atheism as well as compromised Church activity that coexisted with oppositional nationalist projections. The alleged offence against Saint Tamar displays the intricate connection of religion, gender, the nation and traditionalist understandings of social coexistence as outlined above, Bugadze’s main focus being crude radicalism and the absurd social side effects of this revival of Orthodoxy under the auspices of nationalism. The book is also instructive with regard to the role of religion and the Church in Georgia’s relationship to Russia, hence with the question of “unity in faith,” religious difference and their role in the Georgian-Russian decolonization process. Especially in the passages that deal with the war of 2008, in which the province of South Ossetia was occupied by Russia, the latter is presented as an ever-interfering superpower neighbor that invades and occupies territories as it desires, using the Orthodox Christian affinities strategically—and with the active support of Georgian clergy—to ease the enragement about the territorial offence. Bugadze exemplifies this in a funeral ceremony in which the Russian troops celebrate themselves as brothers in the Orthodox faith with their generously treated Georgian enemies:

The [Georgian, ML] patriarch solemnly enters the city of Gori [Stalin’s birthplace, ML] that is occupied by the Russians and celebrates the mass in an occupied church. The [Russian, ML] general is bareheadedly standing aside him. Afterwards the patriarch walks down the stairs holding on to the general’s arm. This means, Russia does not fight against the Georgian people, but against the Georgian government. This means, the great Orthodox country stays friends with the minuscule Orthodox country (Bugadze 2018, 434–35).

This thoroughly staged scene, in which religious and military hierarchies are deliberately blurred and entangled, represents a typical case of the employment of “unity in faith” as an ideological tool to exert control over Georgia, but notably not only by the Russian side, but also by the Georgian Orthodox authority. But this fact is stated rather soberly and certainly does not represent the novel’s main concern. In A Small Country, Russia is rather used as the key word for the encrusted economic and social structures that certain parts of Georgian society—namely the Western-oriented liberal elite that the author as well as his alter ego in the novel are part of—desperately want to overcome.

In order to show the younger generation’s criticism, Bugadze’s narrator proceeds as iconoclast in the literal sense, and his choice of a female saint is hardly coincidental but shows the pertinence of a chauvinist worldview in which female bodies are subject to the male gaze and male judgement. He refers to a number of famous icons of Tamar which depict a woman with strongly visible eyebrows. Instead of perceiving the icon in what Clifford Geertz calls a “religious perspective,” as a manifestation of a transcendental truth, he beholds it like a photo of somebody with a cosmetic abnormity and consecutively reflects about whether describing Tamar’s monobrow is blasphemous and under what conditions artists may at all touch up national saints. Moreover, Bugadze reflects on the fatal entanglement of the Georgian elites with established and in tendency self-contained power structures, be they Soviet or post-Soviet, nationalist or ecclesiastical. In crucial passages of the novel the eminent influence and power of the patriarch, an undisputed fact in Georgia’s political reality (Gurchiani 2021, 104), are described as ambivalent, as a game with expectations, really. “At once I understood, no I discovered: If anybody here was waiting for something, then it was not for my answer […], but for which questions the patriarch would ask and how determined he presented himself. All eyes were on him, not me” (Bugadze 2018, 410). The patriarch’s power and his authority do not originate in himself or in some higher religious truth, they are only ascribed to him by his Georgian Christian followers, which makes him a slave of his own popularity. Notably, like Viktoria Lomasko, Lasha Bugadze hence treats church and religion as a secular force; transcendental questions generally remain beyond their scope. Instead, for Bugadze the patriarch is symbiotically tied to the government, which ironically means the Orthodox-turned Communist Eduard Shevardnadze who was in fact baptized by Ilia II. himself (Metreveli 2021, 63). This reflects the ambiguous stance of Church authorities towards the various wings of the early post-Soviet nationalist movement and the government (Metreveli 2021, 60), to which the church was at times closely related, resulting in the conclusion of the 2002 concordat that among other things privileged the Georgian Orthodox Church in restitution claims (Metreveli 2021, 63; Kekelia 2015, 127, 131). The novel contains the description of a pompous and tasteless ceremony in which the Georgian patriarch and Shevardnadze preside over the cornerstone ceremony for the new Holy Trinity (Sameba) Cathedral in Tbilisi, the biggest donor for which was a Jew (Bugadze 2018, 206). In the novel, a few zealous clerics are presented as members of organized crime or connected with the Secret Service, including its ties to the former Soviet KGB. Once people of such a background protested against the travesty “The First Russian,” the stumbling block of the affair, their reaction may just as well have been motivated by the wish to defend Russia (Bugadze 2018, 362). The enragement about Bugadze’s alleged slander of Tamar in that case could have been a smoke screen for the rehabilitation of the humiliated prince Iurii Bogoliubskii, who prefigured the imperial Russian Romantic scheme of desiring and attaining the Caucasian woman. After all, Tamar would not contend with Iurii’s impotence, in other words his inability to satisfy her sexual and dynastic desires, which in a patriarchic view would be “shameless” on her behalf and an unbearable humiliation on his. The offence against Russia total is no less blatant: unable to satisfy Georgia / the Caucasus, it instead turns to sodomy! To make things worse, Tamar’s defenders in Bugadze’s A Small Country are exactly those people who in the name of the holy nation call for censorship and stand united under the first and foremost “Russian,” Eduard Shevardnadze, the incarnation of Soviet Georgia (Bugadze 2018, 258).

Bugadze’s novel’s great strength is the nuanced view of the author figure’s religiously offended antagonists. Shevardnadze is not reduced to a scapegoat, incarnating the failures of Sovietization. On the contrary, he is a father figure that almost magically produces loyalty among whatever audience he addresses and who during his presidency draws criticism for the only reason that the religious authorities have become sacrosanct and untouchable. Even those Christians who are enraged by “The First Russian” and consider it blasphemous are shown as a group with diverse motivations and allegiances, naïve religiosity next to hypocrisy, priests in pursuit of an ecclesiastic career next to the instrumentalized mob.

In the scandalous turmoil that the novel describes, “Russia” thus is a mere catchword that serves to externalize conflicts in a society that is fatally self-centered, not least because of its tribal fabric that connects society by family and social onuses, a patriarchic view of women included. What is metaphorically called “Russia” actually is something within Georgian society, a metonymy or rhetorical trope that ties the Georgians together against an abstract enemy: all that is done wrong by Georgians in Georgia, including supporters of Orthodox “unity in faith.” Against this backdrop the Georgian political mantra of a decision between East and West, between the Russian Empire and Europe appears to be a mere rhetorical strategy that is cynically employed to present random political choices as inevitable and forms bonds which prevent the nation from embracing a truly post-Soviet decolonial future as a modern, liberal society that would also have to critically reassess its national traditions.

In the novel, Bugadze’s narrator comments on a film project that resonates with his observations of the functioning of Georgian society. He writes about “a small country that is convicted to eternal flippancy, a great parody on a little country that simulates being a serious nation and a serious country” (Bugadze 2018, 568). While this diagnosis can easily be explained by Georgia’s postcolonial or post-imperial situation that produces behavioral patterns designed for hegemonial outer viewers (be it Russia or “the West”), the function of the religious link (“unity in faith”) between Russia and Georgia in this unequal relationship strikes me as remarkable. Even under Communism the Georgian Orthodox church enjoyed a certain autonomy, and religion, particularly by means of its cherishing in the private sphere, became the cradle of anti-Soviet resistance and nationalism. But this influence came at the price of a close alliance with the state, first the Soviet and then the post-Soviet Georgian state. At the same time, history’s irony, this is a striking similarity with the Russian Orthodox Church that has a long symbiotic history with the Russian state and now willingly supports neo-imperial and nationalist political action, even war against Orthodox brothers in Ukraine.

Conclusion

Viktoria Lomasko’s Georgian travel feature and Lasha Bugadze’s documentary novel, whose struggle with their countries’ specific nationalist discourse and colonial heritage regarding religion I showed in my analysis, share some fundamental insights and argumentative strategies. Both address the fact that Orthodox Christianity, employing the concept of “unity in faith,” functions as a hegemonic discourse not only within Russia and Georgia, but also more generally in Russia’s relation with neighboring countries, where Orthodoxy is claimed as Russian property and used as political and spiritual leverage for promoting political cooperation. In Lomasko’s case the critique of “unity in faith” entails a reconsideration of the imperial-turned-nationalist concept of the Russian World, in which she displays a hybrid set of anti-imperial, Soviet and Western attitudes towards Georgia. Remarkably, situations of religious contact are also conceptualized in similar ways in both works, as they focus on differences within Orthodox Christianity. Budgadze even restricts his view to the Georgian Orthodox Church. The two writers also unanimously stress the exclusive role assigned to Orthodoxy in their respective national discourses that render minorities almost invisible. Moreover, both authors reflect about the traditional gender concepts that the Orthodox Church reinforces as part of the national discourse in the post-Communist realm and take a western liberal stance against it, although Bugadze retains elements of patriarchal views on women. But even though both critical, secular works ponder the functioning of Orthodoxy in the context of the Georgian-Russian colonial relation, their works refrain from clear-cut guilt discourse, let alone of nationalist tinge. When read as complementary works, both works’ fundamental repudiation of the markedly post-Soviet alliance between Church and state is striking. “Unity in faith” connects Russian and Georgian Orthodox antiliberal agendas that bring neo-imperialist Russians and nationalist Georgians in close proximity.

References

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London ; New York: Routledge.

Bremer, Thomas. 2015. “Die Russische Orthodoxe Kirche und das Konzept der ‚Russischen Welt‘.” Russland-Analysen 289: 6–8.

Bugadze, Lasha. 2018. Der erste Russe. Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurter Verlagsanstalt.

Caffee, Naomi. 2013. “Russophonia: Towards a Transnational Conception of Russian-Language Literature.” PhD diss, Los Angeles, CA: University of California.

Cheskin, Ammon, and Angela Kachuyevski. 2019. “The Russian-Speaking Populations in the Post-Soviet Space: Language, Politics and Identity.” Europe-Asia Studies 71 (1): 1–23.

Chkhaidze, Elena. 2018. Politika i literaturnaia traditsiia: Russko-gruzinskie literaturnye sviazi posle perestroiki [Politics and literary tradition: Russian-Georgian literary relations after the Perestroika]. Moscow: NLO.

Darieva, Tsypylma Mühlfried, Florian Tuite, and Kevin. 2018. “Introduction.” In Sacred Places, Emerging Spaces: Religious Pluralism in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, edited by Tsypylma Darieva, Florian Mühlfried, and Kevin Tuite, 1–17. New York / Oxford: Berghahn.

Dragadze, Tamara. 1988. Rural Families in Soviet Georgia: A Case Study in Ratcha Province. London / New York: Routledge.

Gertsen, Aleksandr. 1858. Russkoi Narod I Sotsializm. Pis’mo K I. Mishle Iskandera (Perevod S Frantsuzkogo) [The Russian People and Socialism. Iskander’s Letter to I. Michelet (Translation from French)]. London: Trubner & Co.

Grant, Bruce. 2009. The Captive and the Gift: Cultural Histories of Sovereignty in Russia and the Caucasus. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Grdzelidze, Tamara, Martin George, and Rev Lukas Vischer, eds. 2006. Witness Through Troubled Times. A History of the Orthodox Church of Georgia, 1811 to the Present. London: Bennett and Bloom.

Gurchiani, Ketevan. 2021. “Women and the Georgian Orthodox Church.” In Women and Religiosity in Orthodox Christianity, edited by Ina Merdjanova, 101–28. New York: Fordham University Press.

Ifact, Investigative Journalists’ Team. 2020. “Transfiguration of the Catholicos Patriarch of Georgia.” Ifact. 2020. https://ifact.ge/en/transfiguration-of-the-catholicos-patriarch-of-georgia/.

Kekelia, Tatia. 2015. “Building Georgian National Identity: A Comparison of Two Turning Points in History.” In Religion, Nation and Democracy in the South Caucasus, edited by Alexander Agadjanian, Ansgar Jödicke, and Evert van der Zweerde, 120–34. London / New York: Routledge.

Kudaibergenova, Diana T. 2019. “The Body Global and the Body Traditional: A Digital Ethnography of Instagram and Nationalism in Kazakhstan and Russia.” Central Asian Survey 38 (2): 363–80.

Laruelle, Marlene. 2015. “The ‘Russian World’: Russia’s Soft Power and Geopolitical Imagination.” In Center on Global Interest Papers (May). Washington: Center on Global Interests.

Layton, Susan. 1994. Russian Literature and Empire: Conquest of the Caucasus from Pushkin to Tolstoy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lomasko, Viktoria. 2016. “Poezdka v Tbilisi [Journey to Tbilisi].” Colta.ru. 2016. https://www.colta.ru/articles/specials/11409-poezdka-v-tbilisi.

Maisuradze, George, and Franziska Thun-Hohenstein. 2015. Sonniges Georgien. Figuren des Nationalen im Sowjetimperium [Sunny Georgia. Figures of the national in the Soviet Empire]. Berlin: Kadmos.

Manning, Paul. 2012. Strangers in a Strange Land. Occidentalist Publics and Orientalist Geographies in Nineteenth-Century Georgian Imaginaries. Boston: Academic Studies Press.

Metreveli, Tornike. 2021. Orthodox Christianity and the Politics of Transition: Ukraine, Serbia and Georgia. London / New York: Routledge.

Ryklin, Mikhail. 2007. Mit dem Recht des Stärkeren: russische Kultur in Zeiten der “gelenkten Demokratie” [The right of the stronger. Russian censorship in the era of “managed democracy”]. Bonn: bpb.

Sahni, Kalpana. 1997. Crucifying the Orient. Russian Orientalism and the Colonization of Caucasus and Central Asia. Bangkok: White Orchid Press.

Slezkine, Yuri. 1994. “The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism.” Slavic Review 53 (2): 414–52.

T.A.S.S. 2019. “Postpred Rossii pri ES nazval russkii narod samym mnogochislennym razdelennym v mire.” 2019. https://tass.ru/politika/7302117.

Versaci, Rocco. 2008. This Book Contains Graphic Language. Comics as Literature. New York: Continuum.

Von Lilienfeld, Fairy. 1993. “Reflections on the Current State of the Georgian Church and Nation.” In Seeking God: The Recovery of Religious Identity in Orthodox Russia, Ukraine, and Georgia, edited by Stephen K. Batalden, 221–31. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

White, James. 2020. “Introduction.” In Unity in Faith? Edinoverie, Russian Orthodoxy and Old Belief, 1800-1918, edited by James White, 1–22. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Zabirko, Aleksandr. 2015. “Literaturnaia genealogiia konceptsii ‘Russkii mir’: ot Bednoi Lisy do polkovnika Girkina [The literary genealogy of the concept ‘Russian World’: from the Poor Lisa to Colonel Girkin].” Forum noveishei vostochnoevropeiskoi istorii i kul’tury 2: 114–37. http://www1.ku-eichstaett.de/ZIMOS/forum/inhaltruss24.html.

Zviadadze, Sophie. 2021. “Religion in the South Caucasus: Tradition, Ambiguity, and Transformation.” Journal of Religion in Europe 14: 204–23.

Research for this article was made possible by a fellowship of the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation.↩︎

The mutual perception of Christian Georgians and Muslim Georgians in the late nineteenth century is a particular case in point; see Paul Manning (2012), 147–149.↩︎

For a detailed history of Georgian autocephaly, see Tamara Grdzelidze et al. (2006), 107 and 192–244.↩︎

For a detailed report and analysis of the case, see Mikhail Ryklin (2007).↩︎

See Lomasko’s interview with the German public radio station Deutsche Welle, published 21.02.2013, DW. “Viktoriia Lomasko: “Risunki uzhe sushchestvuiut, a mne ikh nado tol’ko proiavit’.” [The drawings already exist, I just have to bring them to light]. Accessed April 14, 2021. https://www.dw.com/ru/виктория-ломаско-рисунки-уже-существуют-а-мне-их-надо-только-проявить/a-16617405.↩︎

Lomasko reflects on her work in relation to the Soviet colonial orientalist (in the Saidian sense) tradition in a presentation entitled “I am the Last Soviet Artist” given at Kunsthalle Wien (March 6, 2020), accessible on youtube: Kunsthalle Wien, “Wednesday with… Victoria Lomasko: I am the last Soviet artist,” YouTube Video, 1:04:41, March 6, 2020. Last accessed November 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDyaeUnrtLo.↩︎

An altered English version can be found here: Viktoria Lomasko, “In Tbilisi. “It’s forbidden to be sad in Georgia.”” n+1 27 (winter 2017). Las accessed April 14, 2021. https://nplusonemag.com/issue-27/essays/in-tbilisi/.↩︎

On Central Asia in a feminist decolonial perspective, see Vika Kravtsova. “Chto znachit dekolonizirovat’? Dekolonizatsiia, feminism, postsovetskoe,” [What does decolonizing mean? Decolonization, feminism, the post-Soviet] Krapiva (30 December 2019). Last accessed April 14, 2021. https://vtoraya.krapiva.org/chto-znachit-dekolonizirovat-30-12-2019.↩︎

«Мне кажется, что и в советское время люди чувствовали негласную иерархию. Русские были титульной нацией. Белорусы и украинцы — младшими братьями. Потом кавказские народы — они не славяне, от нас дальше, но у них древняя культура, солнце, море и вкусная еда. И, наконец, народы Средней Азии, чьи территории были насильственно присоединены в ходе колониальных войн, а в советская время достаточно произвольно поделены на республики», — размышляет Виктория.

Ekaterina Krasotkina. “Nevidimye I razgnevannye,” [The invisible and the angry] Takie dela. Last accessed April 14, 2021. https://takiedela.ru/2018/04/nevidimye-i-razgnevannye/↩︎

On women in Georgian Orthodoxy, Soviet and post-Soviet, see Gurchiani (2021).↩︎

For a detailed report and analysis of the case, see Ryklin (2007).↩︎

https://humanrightshouse.org/articles/georgia-passes-antidiscrimination-law/. Last accessed September 14, 2022.↩︎

I am grateful for Jesko Schmoller’s insightful remarks on religion in the post-Soviet realm.↩︎

На Кавказе есть термин, обозначающий правильное поведение человека в обществе: на азербайджанском и на армянском — «намус», на грузинском — «намуси». Для мужчины намус значит честь, совесть. Для женщины намус связан исключительно с сексуальным поведением, с ее недоступностью.↩︎

Dar’ia Radova. “Viktoriia Lomasko: o razdelennom mire I Poslednem sovetskom khudozhnike,” [Viktoria Lomasko: about the divided world and the last Soviet artist] Zima magazine. Last accessed April 14, 2021. https://zimamagazine.com/2019/05/lomasko-separated-world/?fbclid=IwAR11F8L5kyCJnqA-Tp7SkO9wy6HBt\_2l8gBwTopd8QMzBw8oiozUixEHdYI.

С основной композиции, которую сама для себя я назвала «Русский мир»: на фоне странных руин, среди сорных трав стоят коммунисты, дореволюционные персонажи, девочка с флагом, символизирующая новые патриотические настроения, а также фигуры моих родителей. Папа держит в руках свою картину «Клоунада» с критикой путинского режима, с которой он выходит на демонстрации в Серпухове. Руины церкви и сорняки олицетворяют бесхозность современной России↩︎

The Georgian text “The First Russian” was published in a journal in 2002; in 2017 it was followed by a documentary autobiographical novel about its reception, entitled A Small Country. In the German translation that I used for this article the latter bears the title of the first, Der erste Russe (2018).↩︎