Conjuring Planetary Spirits in the Twenty-First Century: Textual-Ritual Entanglements in Contemporary ‘Magic(k)’

This article illustrates textual-ritual entanglements in Western learned magic across almost two millennia through an analysis of Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience. Frater Acher is a contemporary practitioner of ‘magic(k)’ who, between 2010 and 2013, performed a series of conjurations of six planetary spirits inspired by an early modern manual of learned magic named Arbatel. Frater Acher combined the Arbatel with ritual techniques from numerous further contexts, among them the late ancient Greek Magical Papyri, the Clavicula Salomonis tradition, Paracelsianism, Hermeticism, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, theurgy, modern imagination techniques, as well as chaos ‘magic(k)’. As a consequence, Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience—as he frames his ritual diaries published online—reveals a strikingly entangled ritual that illustrates the breadth, depth, and complexity of Western learned magic, as well as its manifold entanglements across time and space. His diaries also demonstrate that, even while following largely formalistic premodern scripts of learned magic, contemporary practitioners may nonetheless display a high degree of flexibility, creativity, and innovation. The article closes by reflecting on whether it is likely that such strategies were also present in premodern practitioner scenarios. In doing so, it calls for taking the—extensive but hitherto almost completely neglected—data of experience reports by contemporary practitioners of ‘magic(k)’ into account when interpreting premodern sources of learned magic. As a consequence, this is the first systematic attempt to compare and juxtapose premodern and modern interpretations and mindsets of practitioners of learned magic. It is thus also the first scholarly article that aims at elucidating a premodern manual of learned magic through reading and analysing the experience report of a contemporary practitioner.

Magic, rituals, entangled history, history of magic, grimoires, Arbatel, conjuring spirits, occultism, Hermeticism, contemporary esotericism, Frater Acher

Introduction

Contemporary ‘magic(k)’1 is a vast, highly complex, and unexpectedly heterogeneous, but also extremely fascinating, field of research. At the time of writing, we lack even a tentative overview of its multitudinous currents, its diverse groups and sub-groups, its manifold ritual techniques, its hundreds of thousands of protagonists (including both the recognizable leaders and authors as well as its ‘invisible’ practitioners), its enormous textual output, its ongoing appropriation and production of ritual sites and artefacts, its use of media and hence its public (in)visibility, its political struggles and agendas (consider the recent Bind Trump movement),2 its moral and legal implications, and its ongoing tendency to change and innovate. If we wish to squeeze contemporary magic(k) into established categories of the study of religion, and thus look at it in the sense of ‘contemporary esotericism’ or a ‘new religious movement,’3 while at the same time acknowledging its enormous textual output, it seems obvious that magic(k) is a strikingly understudied topic in the study of religion. The scholarly community is only slowly becoming aware of the depth and complexity of both contemporary magic(k) and the broader tradition to which it belongs, that of Western learned magic. Similarly, scholarship has only recently begun to take modern practitioners of magic(k) seriously beyond frames of reference drawn from well-worn master narratives or age-old stereotypes (these are often related to polemical characterisations of ‘occultism’ that associate it with unverified and unverifiable pseudo-knowledge, neurotic escapism, naïve self-delusion, or egocentric megalomania).

The present essay cannot, of course, compensate for this lacuna in the modern study of religion. Its main purpose is to present a single but telling case study from the twenty-first century that ties well to the other articles in this special issue. It does so by highlighting textual, conceptual, and ritual continuities from many of the sources presented in the other articles of this issue, but also by discussing interesting innovations, re-configurations, and re-interpretations of the art by a contemporary practitioner. The article also demonstrates the value in studying premodern manuals of learned magic as more than just dry, dead texts. Instead, we can usefully view them through the lens of the experiences of modern practitioners who have, much like experimental archaeologists, given these ritual manuals a trial and tested what works (for them) and what does not, often charting their observations in a systematic manner. Studying modern practitioners of premodern texts of learned magic also allows for interesting analytical juxtapositions of the original contexts and mind-sets of these texts (if we are able to reconstruct them) and the—obviously—very different circumstances and mind-sets of their (post-)modern practitioners.

The case study at the centre of the present article is a series of conjurations of planetary spirits performed by an informant of mine between the years 2010 and 2013. The informant followed—while also reinterpreting and expanding upon—an early modern ritual script of learned magic commonly known as Arbatel. The informant is an experienced German practitioner of magic(k) who has published several books and e-books under the pseudonym “Frater Acher” and also runs a much-frequented website named theomagica.com. I had several in-person and email conversations with Frater Acher, but my main sources for this article are the excerpts of his ritual diaries—published online—in which he recalls and narrates his experiences before, during and after the aforementioned series of conjurations. Frater Acher’s Arbatel conjurations demonstrate several interesting ambivalences inevitably faced by contemporary practitioners of magic(k). These include the oscillation between traditionalist or creative/innovative approaches towards the ritual art, between psychological or spiritual interpretations of evoked entities, and between identifying the purposes of magic(k) as oriented towards either inner-worldly benefits or self-transformation.

The article is structured as follows. In order to tie properly to the other articles in this special issue, section 1 will first discuss contemporary magic(k) as a distinct and promising field of research, outlining the criteria that allow for the delineation of the field and tying it to the longue durée tradition of Western learned magic. The section will then go on to provide a brief glimpse into Frater Acher’s biography, his career and motivations as a contemporary practitioner of magic(k), and my personal acquaintance with him. Section 2 presents a description of the original Arbatel, based on the first printed edition of 1575, outlining its history, ritual structure, and purpose. Section 3 describes and analyses Frater Acher’s conjuration of Phul, Ophiel, Hagith, Och, Phaleg, and Bethor (he omitted the conjuration of the seventh spirit ascribed to Saturn for reasons outlined below) and discusses some of the insights that he claims to have gathered during and after these conjurations. Section 4 concludes by discussing the dynamics and textual-ritual entanglements of Western learned magic as a living tradition that extends from late Antiquity to the twenty-first century, and provides some tentative answers to a question that might emerge while reading this article: Why conjure planetary spirits in the twenty-first century by following a ritual script that is more than 400 years old?

Contemporary Magic(k)

Delineating the Field

As has already been mentioned, the notion of contemporary magic(k) used in this article is tied to my conceptualisation of Western learned magic (Otto 2016). Accordingly, I argue here that the main criterion for gathering research data outlined in my Aries article on historizing Western learned magic—“I will only focus on […] sources that include an etymological derivate, linguistic equivalent or culturally established synonym of ‘magic’ as a self-referential and thus identificatory term” (2016, 173)—can also be applied to delineate the field of contemporary magic(k). Countless contemporary practitioners make frequent use of the term (spelled either with or without the ‘k’), so the criterion seems to work perfectly well for collecting and studying practitioner discourses from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.4

There are two advantages and two disadvantages to applying this discursive strategy5 to delineate the field of contemporary magic(k) when compared to, for example, using a mono- or polythetic working definition with a fixed set of defining criteria. The most important advantage is that contemporary magic(k) can be interpreted as being part and parcel of the textual-ritual tradition of Western learned magic. As this tradition is characterized by both continuity and changeability from late Antiquity to the present day (see Otto 2016, 183–99), contemporary magic(k) can fruitfully be analysed for its use of and reliance upon premodern texts of learned magic, its re-interpretations, adaptations, and transformations of these texts, its ritual entanglements (on ‘entangled rituals’ in Western learned magic, see ibid., 201f.), as well as a large number of modern innovations. What is more, a longue durée perspective on contemporary magic(k) allows for the systematic comparison of contemporary magic(k) and the learned magic of previous centuries, thus illuminating both through juxtaposition (see Freiberger 2018, 10). Such a comparison sheds light on changing ritual techniques, concepts of ritual efficacy, practitioner milieus, and moral considerations, as well as further textual and ritual entanglements across time and space. The present article is an example of precisely such an approach.

The second advantage is that the puzzling heterogeneity of contemporary magic(k)—which makes it impossible to delineate the field by means of a substantive definition—remains unproblematic from an analytical perspective. Admittedly, the field encompasses a large number of non-uniform currents (e.g., the Golden Dawn current, the Martinism current, the Thelema current, the Satanic current, the Chaos magic(k) current, the Wicca current, and various neo-pagan and neo-shamanic currents such as the Sweet Medicine Sundance Path, etc.), ritual techniques (e.g., astral magic(k), sigil magic(k), rune magic(k) such as F/Uthark, sexual magic(k), Enochian magic(k), Cthulhu magic(k), Draconian magic(k), Cyber magic(k), Hoodoo, etc.), groups and sub-groups (e.g., The Ordre Martiniste and its offshoots; the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and its offshoots; the Ordo Templi Orientis and its offshoots, the Astrum Argenteum, AMORC, the Fraternity of the Inner Light, the Fraternitas Saturni, the Servants of the Light, the Church of Satan, the Temple of Set, the Illuminates of Thanateros, Amookos, the Dragon Rouge, the Grey School of Wizardry, etc.), a plethora of individual authors and practitioners, an enormous amount of written sources in numerous languages, as well as ritual tools and other aspects of the material culture of learned magic. The heterogeneity of these currents, techniques, groups and sub-groups, authors and practitioners, and textual sources is not problematic from an analytical perspective because the discursive strategy outlined here simply maps the emic use of the concept of magic(k) by contemporary practitioners who, quite naturally (due to certain implications of the conceptual history of magic), continue to subsume a large variety of things under the concept. As Western learned magic has been an entangled tradition and a multifaceted ritual art since its earliest days (see Otto 2016, 199–203), it is as necessary as it is rewarding to map these manifold nuances and entanglements without falling prey to the temptation to look for a unifying core.

Whereas the analytical foci of continuity, changeability, heterogeneity, and hybridity provide important methodological advantages of the discursive strategy proposed here for delineating the field of contemporary magic(k), there are also two methodological consequences that we might perceive as disadvantages. The first disadvantage relates to the thematic boundaries of the field. Things not considered magic(k) by modern practitioners will automatically fall outside the research field, even though we may have reasons to include them. For example, advocates of the New Thought Movement teach basic visualisation techniques for individual wish-fulfilment, often focused on the acquisition of wealth (consider the book and documentary The Secret). There is today in fact a huge market for such self-help techniques, partly inspired by New Age interpretations of the Human Potential Movement, as is clearly shown by examples such as the online self-improvement curriculum Mindvalley (https://www.mindvalley.com/; accessed February 05, 2023). Many of the techniques propagated here are also applied in contemporary magic(k), but protagonists of the New Thought movement or of Mindvalley typically avoid the term ‘magic’ for strategic reasons. We might also think of contemporary esoteric practitioners who believe in and instrumentalise archangels for all sorts of inner-worldly purposes—similar to, say, contemporary practitioners of Enochian magic(k) (see Asprem 2012)—but who deliberately avoid the term ‘magic’ or even use it as a pejorative label to refer to other practitioners only. Since this type of boundary work is part of the game and as we are applying a discursive rather than a substantive criterion to delineate the field, these things will, however interesting, necessarily fall outside the horizon of our analysis, initially at least. Yet, in a second step, it may also be viable and fruitful from a discursive perspective to trace the magic(k)al roots of practices and ideas that eventually came to penetrate discourses on neurolinguistic programming or visualisation techniques, even though the latter would not belong to the field of contemporary magic(k) in a strict sense. Even though some interesting cases will have to be neglected for the moment, the discursive approach suggested here still yields more than enough data to ponder.

The second disadvantage relates to the geographical, cultural, and linguistic boundaries of the field.6 Where does it begin and where does it end, given that the world is today largely interconnected through global markets, brands, technologies, media, and the internet? Do we only include Europeanist practitioners, or also Crowley-readers from China, India, or Tanzania? What about synonyms for magic(k) in languages such as Hebrew or Arabic? Should we include contemporary Israeli practitioners of qabālā maʿăśīt (practical kabbalah) or a contemporary Egyptian saḥir who fabricates wufuq (numerological talismans)? What about syncretistic currents such as Haitian Vodou or Brazilian Umbanda, which have been inspired in part by the textual-ritual tradition of Western learned magic but have also been shaped by other trajectories? There are no easy answers to these questions, but my own strategy will be to decide pragmatically on a case-by-case basis. Given our contemporary focus, the field is alive, ever-changing, and its boundaries continue to shift and blur. The discursive strategy proposed here works precisely by acknowledging these floating boundaries. The field is obviously there, however amorphous, and scholars of contemporary magic(k) have every right to make strategic yet pragmatic decisions about what to include in the scope of their studies.

The Case of Frater Acher

Despite the complex questions relating to the inclusion of edge cases when considering the field as a whole, the example discussed in the following falls rather straightforwardly within our area of focus. Frater Acher readily admits that he “has studied Western Ritual Magic in theory and practice at I.M.B.O.L.C. and has been actively involved in magic as a lone practitioner for more than twenty years.”7 Frater Acher8 is a middle-aged German national currently residing near Munich, Germany. According to his self-description, he “holds an MA in Communications Science, Intercultural Communications and Psychology as well as certifications in Systemic Coaching and Gestalt Therapy.”9 I.M.B.O.L.C. (Internationale magische Bildungsstätte für okkulte Lebenskunst und Credo: https://www.magielernen.de/; accessed February 05, 2023), where Frater Acher underwent his training, currently offers one of the most elaborate and demanding distance learning courses on magic(k) in the German-speaking world.10 Its curriculum consists of seven modules and 33 ‘didactic letters’ (Lehrbriefe), each of which takes a minimum of 3 months to complete. The entire curriculum thus requires a time investment of roughly 10 years, based on 1–2 hours of daily practice.11 The person responsible for I.M.B.O.L.C. is another German national who has run this educational establishment since the early 1990s under the pseudonym of Agrippa. Agrippa dedicated much of his early career as a practitioner of magic(k) to a London-based branch of the Golden Dawn, but pursued his own trajectory from 1992 onwards by founding I.M.B.O.L.C. His training covers the conjuring of spirits, kabbalah, Tarot, astrology, numerology, alchemy, concentration and imagination techniques, yoga, dream interpretation and control, language training (e.g., Latin, Hebrew), astral projection, and numerous other ritual and mind-oriented techniques. In an interview I conducted in September 2018, Agrippa claimed that I.M.B.O.L.C. emerged in the late 1990s as one of the first internet-based distance learning courses on magic(k) in the German-speaking world, and that he had trained circa 500 students over the past three decades.12 Agrippa never entered the public sphere as an author (apart from his course website), in stark contrast to Frater Acher, who passed through large parts of the I.M.B.O.L.C. curriculum over the course of roughly the first decade of the new millennium.

Frater Acher is now a fairly well-known name in contemporary magic(k) due to his website www.theomagica.com, on which he regularly publishes essays, experience reports, practical tips and exercises, and historical speculations. He also offers a number of downloadable electronic tools that facilitate the practice of magic(k)—such as excel tables that calculate numerological squares, gematria results of random words based on the Sepher Sephirot, or the possible name of one’s own genius (“holy guardian angel”: see Bogdan’s chapter in this issue for further details on this concept, 2023) based on one’s birth horoscope. Frater Acher’s opening remarks on the website run as follows:

Welcome to theomagica.com, on the safe side of Frater Acher’s temple. As a service to our community, I offer here things I have found of value in the course of my mago-mystical explorations, may these be goêtic or theurgic in nature. In particular, you can find on this page free ebooks, in-depth essays, and my regular blog updates. […] Today, I have been actively involved in magic for more than twenty years. I am a German national, and after several years of living abroad, returned to Munich, Germany in 2009.13

At the time of writing, Frater Acher is also the author of two e-books (In search of a holy magic;14 On the order of the Asiatic brethren15) and eight printed books (Cyprian of Antioch: A Mage of many faces [2017]; Speculum Terræ: A Magical Earth-Mirror from the 17th Century [2018]; Holy Daimon (2018]; Black Abbot: White Magic [2020]; Rosicrucian Magic: A Reader of Becoming alike to the Angelic Mind [2021]; Clavis Goêtica: Keys to Chthonic Sorcery [2021; co-written with José Gabriel Alegría Sabogal]; Ingenium—Alchemy of the Magical Mind [2022]; and Holy Heretics [2022]), all published in English. Theomagica.com also includes a blog where Frater Acher posts occasional reflections on his current practice.16 To my knowledge, Frater Acher has not been the subject of any previous academic study.

In addition to his publishing activities, Frater Acher is, together with British practitioner Josephine McCarthy, the co-founder of www.quareia.com (accessed February 05, 2023), another extensive, online-based distance learning course in contemporary magic(k). Unlike most other existing teaching curricula in this precarious field of knowledge, all of its 30 modules are available on the website free of charge (“Quareia is a new school of magic for the 21st century. It is open to anyone, everywhere. Its content is entirely free of cost.”).17 Josephine McCarthy is well-known in the scene for her concept of a visionary magic(k) that works predominantly through imagination and mind-based techniques. She has outlined this approach in a trilogy of books entitled Magical Knowledge (re-published 2020 with Quareia Publishing). Quareia furthermore offers a distinct set of Tarot cards (the ‘LXXXI magicians set’) and a corresponding interpretation system.

Frater Acher also runs another project, a website dedicated to the transcription and translation of manuscripts of the Leipzig collection of ‘codices magici’ from the early eighteenth century (www.holydaimon.com, accessed February 20, 2023). This collection was the topic of my book Magical Manuscripts in Early Modern Europe: The Clandestine Trade in Illegal Book Collections, co-authored with Daniel Bellingradt (2017), which led to my first meeting with Frater Acher, who attended a conference in Leipzig where I presented the findings of my work. We remained in contact thereafter. Frater Acher works together with several university-trained people who are able to read and transcribe early modern German handwritings.18 As of today, seven manuscripts of the collection have been transcribed and translated into English on holydaimon.com, where they are presented in a graphically appealing way.

Frater Acher apparently undertook training in a large number of modern currents and techniques of magic(k), from the Golden Dawn to Chaos magic(k) and beyond, but he is probably best characterised as a ‘traditionalist.’ In other words, he is a contemporary practitioner with a particular fondness for premodern texts of learned magic, which he seems to deem more accurate, trustworthy, and inspiring than most of the (post-)modern sources. This is clearly visible in his dedication to the holydaimon.com project, where he relates his underlying intention to trace and uncover an original, unbiased tradition of medieval Christian angel magic (e.g., in the works of Pelagius) that he may eventually use in his own ritual work (see especially his recent work on Trithemius: Black Abbot: White Magic [2020]). Yet, these ‘traditionalist’ interests have not prevented him from combining all sorts of modern—i.e., twentieth and twenty-first-century—ritual techniques of magic(k) with those outlined in premodern sources such as the Arbatel. Hence, before delving into Frater Acher’s re-interpretation of this text and his practical experiences therewith, let us first consider the contents of the original Arbatel.

The Arbatel

Historical Context

The Arbatel is a Latin text of learned magic that was first printed in 1575 in Basel by Peter (or Petrus) Perna under the title ARBATEL DE MAGIA VETERUM. That 1575 was the date of the text’s first appearance has been argued by Carlos Gilly, who has shown that all printed editions that display earlier dates on their title pages (1510, 1531, 1564) are, in fact, later fabrications (2005, 209). Even though the printing of the Arbatel caused a scandal in Basel at the time, the text was sufficiently popular to justify several re-editions and translations in both printed and manuscript form. From 1579 onwards, it was frequently appended to printings of Agrippa of Nettesheim’s Opera Omnia, and an English translation circulated from 1655 onwards as an appendix to Robert Turner’s English edition of Ps.-Agrippa’s spurious Fourth book of occult philosophy (see Davies 2009, 52). The first German translation of the Arbatel was printed by Andreas Luppius in 1686. The Arbatel also circulated widely in manuscript form from the late 1570s onwards, including early German translations that were also re-translated into Latin before the end of the sixteenth century. As a consequence, an ever-larger number of different versions and translations of the Arbatel circulated in early modern Europe, and in the light of its enthusiastic reception, the text can be seen as something of an early modern best-seller of learned magic. This success is somewhat striking, given that the work was published at the height of the European witch persecutions and was one of the first printed texts to outline detailed techniques for the conjuration of spirits.

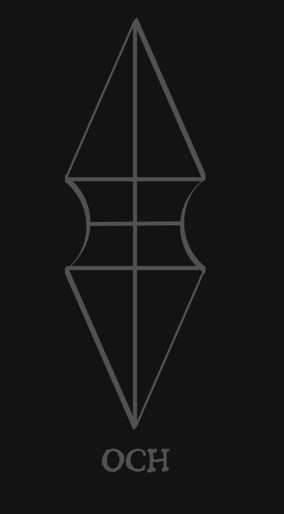

Even though some of the German manuscript translations claim Theophrastus of Hohenheim (Paracelsus) as the Arbatel’s author, an assumption that was also shared by early Rosicrucian sympathisers such as Paul Nagel and Valentin Weigel, its authorship remains unclear today (note that Paracelsus is cited several times in the text). According to Carlos Gilly, the author “was undoubtedly an enthusiastic follower of Hermes Trismegistus and Paracelsus as well as a great expert in Medieval and Renaissance magic” (ibid.). Joseph H. Peterson adds that the author also had “remarkable command of the Bible, which he apparently quoted from memory” (2009, XIV), and offers several convincing arguments for taking the author to be the French Paracelsianist Jacques Gohory (1520–1576). Be this as it may, it is highly likely that the Arbatel was composed after the posthumous publication of Paracelsus’ Philosophia Sagax in 1571, as it draws on that work’s divisions of ‘magic,’19 its unique conceptualisation of ‘magical creatures’ (which include elemental spirits, pygmies, ‘sagani,’ and dryads),20 and particularly its notion of ‘Olympian spirits’—a term that apparently refers to seven spirits ascribed to the seven ‘wandering stars’ of Ptolemaic cosmology which are visible to the unaided eye (Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn).21 The Arbatel furthermore stands in the learned magic manuscript tradition of spirit lists, such as De legionibus angelorum septem planetarum (e.g., Ms. Halle UB, Ms. 14 B 36, 289–296) and De officiis spiritum (e.g., Ms. Coxe 25, fols. 173–87). However, the names that the text’s author ascribes to the seven planetary spirits—ARATRON (Saturn), BETHOR (Jupiter), PHALEG (Mars), OCH (Sun), HAGITH (Venus), OPHIEL (Mercury), and PHUL (Moon)—[see peterson_arbatel_2009, 29f.]22 were a novelty at the time, and they also differ from the list of seven planetary spirits outlined in Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia (book 3, ch. 24).23 The Arbatel was also innovative in its use of the notions of ‘theosophy’ and ‘anthroposophy’ which are here—for the first time—understood as two basic types of positive scientiae of learned magic (see Peterson 2009, 100–101).

The Arbatel is clearly indebted to the humanist discourse on ‘magia naturalis,’ which had been thriving for roughly a century prior to the text’s publication, even though it does not use this particular vocabulary. However, when compared to Marsilio Ficino’s writings on ‘magia naturalis,’ which remained rather cautious regarding its practical application (Ficino outlines the use of herbal medicines, planetary songs, and, rather reluctantly, astrological talismans for healing purposes—see Otto 2011, ch. 10), the Arbatel offers a much more explicit and straight-forward technique for ‘drawing down the power of the stars’24 and thereafter encountering them directly “IN CONVERSATION” (aphorism 16, Peterson 2009, 31),25 either “visibly or invisibly” (aphorism 17; ibid.).

In doing so, the text also ties into much older Islamicate traditions of conjuring planetary spirits, which go back at least as far as the eighth century CE and are usually ascribed to the Sabians of Harran (for further details on this Islamicate trajectory, see Michael Noble’s article in this issue). Some of the planetary conjuration practices of this legendary religious group (which is mentioned three times in the Qurʼān) seem to have survived in the Epistles of the Brethren of Purity (mid-tenth century CE) and particularly in the Ġāyat al-ḥakīm (late tenth century/early eleventh century).26 As is well known, the latter text was translated into Old Castilian and Latin in the mid-thirteenth century under the title Picatrix (see Sophie Page’s article in this issue for further details, (2023)), with the consequence that Islamicate ritual techniques for conjuring planetary spirits were already circulating in medieval and early modern Europe long before the publication of the Arbatel. However, even though such techniques originated in the Arabic-Islamicate world, the Arbatel clearly represents an early modern, heavily Christianised, and decidedly humanist-Paracelsian version of the same basic idea. The text is hence a fine example of longue-durée and trans-religious textual-ritual entanglements in the history of Western learned magic.

The Arbatel’s Christian dimension is not only visible in its more than 70 biblical quotations, but also in the omnipresence of the term ‘GOD’ throughout the text, which appears over 180 times. In fact, the Arbatel stresses over and over again that practitioners should “Love the Lord your God with all your heart” (aphorism 5, Peterson 2009, 15), that the “‘Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,’ and of the beneficial use of all magic” (aphorism 49, 2009, 99), and that they should use the art “with gratitude for the honor of God, and the benefit of their neighbors” (2009, 5). Accordingly, the Arbatel distinguishes between divine, benevolent ‘magic’ on the one hand, and demonic, malevolent ‘magic’ on the other (see also aphorism 38), sharply distinguishing all those “cacomagi, who with forbidden superstitions associate themselves with demons, and although they can achieve certain things which God permits, they in turn suffer punishment from the devils” (aphorism 26, Peterson 2009, 57, see also aphorism 41). It may be that it was this extremely pious varnish that enabled the Arbatel to be printed and continuously re-printed at the height of the European witch persecutions. In fact, the text is often considered to be one of the first decidedly ‘white magic’ texts.27 Frater Acher, as we will see, practiced the Arbatel for precisely this reason.

The Arbatel’s reception and impact was, in the words of Carlos Gilly, quite “overwhelming” (2005, 213). Of course, the Arbatel quickly prompted polemical, indignant, and condemnatory reactions from the authorities of the time, such as Martin Delrio, Andreas Libavius, and the Basel bishop Simon Sultzer (see Davies 2009, 53f.). Much more interesting, however, is the positive or affirmative reception of the work over the following centuries. It influenced many subsequent texts dedicated to the practice of learned magic, including Großschedel’s Calendarium Naturale Magicum Perpetuum (1614), Ps.-Faust’s Magia naturalis et innaturalis, the Sixth and Seventh Book of Moses, a range of French Grimoires of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Ebenezer Sibly’s Clavis or Key to Unlock the Mysteries of Magic (1792), and Francis Barrett’s The Magus (1801), to name just a few. The Arbatel also influenced, directly or indirectly, various authors who contributed to the emerging discourse about ‘Christian theosophy’—such as Valentin Weigel, Heinrich Khunrath, Adam Haslmayr, Johann Arndt, and Benedikt Figulus—as well as a range of other influential figures of the time, including John Dee, Theodor Zwinger, Wolfgang Hildebrand, and Robert Fludd.28 Several versions of the Arbatel also made it into the Leipzig collection of ‘codices magici’ (on which see Bellingradt and Otto 2017),29 with the names of the seven planetary spirits appearing even more frequently in this particular corpus of manuscripts.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Arbatel was re-printed, re-edited and re-translated several times, and was thus easily accessible to modern practitioners of magic(k). Johann Scheible published the 1686 Luppius version in his Das Kloster (vol. III) in 1846 and then a different German translation in his 1855 edition of Agrippa’s Magische Werke. A few decades later, the Berlin-based publisher Herman Barsdorf Verlag also provided a German translation in its five-volume Agrippa compendium Magische Werke in fünf Theilen (1921). The Arbatel seems to have been of particular importance to Franz Bardon, who was one of the leading German-speaking practitioners during the mid-twentieth century and who dedicated several works to the conjuration of planetary spirits, yet without mentioning the Arbatel by name (e.g., Die Praxis der magischen Invokation, 1956). A French translation was published by Marc Haven in 1946 (see Peterson 2009, 103–04). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century milieus of the Golden Dawn, the Arbatel was first popularised through Arthur Edward Waite’s Book of Black Magic and Pacts (1898), but apparently never achieved the prominence of related early modern manuals for conjuring spirits, such as the Clavicula Salomonis or the Abramelin in the Golden Dawn. Aleister Crowley experimented with invoking planetary spirits, possibly inspired by the Arbatel, in his Rites of Eleusis, a series of seven rituals publicly performed at London’s Caxton Hall in 1910 (see Crowley 1911; and Doyle White 2021). However, in his assessment of pivotal premodern texts of learned magic, Crowley obviously preferred the Abramelin over the Arbatel (see Henrik Bogdan’s article in this issue, (2023)). Nevertheless, through Crowley, the Arbatel may also have inspired Gerald Brousseau Gardner and his conceptualisation of the central Wiccan rite of ‘drawing down the moon’ (see Doyle White 2021 for further details). Turner’s English translation of Agrippa’s Fourth book of occult philosophy was reprinted continuously, most recently by practitioner-scholar Stephen Skinner in 1978, which may have prompted renewed interest among English-speaking practitioners from the 1980s onwards.30 In 2009, Joseph H. Peterson produced a novel ‘semi-critical’ bilingual Latin-English version, based on the original 1575 printing, which is also the edition used here. All in all, the Arbatel is one of many striking examples of textual-ritual entanglements in Western learned magic across time and multiple cultural, religious, and linguistic boundaries.

Ritual Mechanics

The mechanics of the Arbatel ritual are surprisingly simple and straightforward, and much less demanding than those set out in other texts of learned magic from that era, such as those belonging to the Solomonic cycle. Solomon is, in fact, not even mentioned in the Arbatel, even though its author clearly adopted a range of ritual patterns from the Clavicula Salomonis and related texts—such as the use of sigils ascribed to spirits, the observance of their respective timeframes and cardinal directions, the divine revelation of their names, and the acquisition of an assistant or guardian angel. The Arbatel is divided into 49 chapters, or ‘aphorisms,’ and covers some 90 pages in a regular book format. The Arbatel ritual (as outlined in the 1575 version) consists of five steps.

The first and foremost prerequisite for successful Arbatel ‘magic’ is the faith of the practitioner. According to aphorism 2, “you should intend to undertake or accomplish nothing without the invocation of GOD through his only begotten Son” (Peterson 2009, 13). Aphorism 39 stresses that the practitioner “should learn to worship, love, and fear the eternal God, and to honor him in spirit and truth” (2009, 79). There are many similar formulations that run through the text like a red thread, and thus amplify the aforementioned 70 biblical quotations and innumerable praises of ‘GOD.’ Of course, the reason for the Christian God’s omnipresence in the Arbatel is that, according to the author’s frame of reference, all creation is bestowed by God, including all arts and sciences, and hence also the ‘magia veterum’ outlined in the Arbatel. Only by being absolutely faithful and obedient towards God and his spirits will the practitioner succeed in the art, as it “is not delivered unless divinely, to those to whom God is willing to reveal these secrets” (aphorism 11, 2009, 19).

If this basic prerequisite is met, the art is taught “through the instructions of the holy spirits of God: Because true faith comes FROM HEARING” (aphorism 12, 2009, 23). From the perspective of the ritual procedure, this claim is primarily related to knowing the spirit’s correct names: “Your GOAL therefore must be that you master the names of the spirits, that is their office and powers, and how they are subjected to your ministry or service by God” (aphorism 13, 2009, 25). The Arbatel suggests that the practitioner ask for an angelic assistant or transmitter, and for this purpose provides a brief prayer to God, who shall grant the practitioner “one of your spirits, who will teach me whatever you wish me to learn and understand” (aphorism 14; ibid.). In aphorism 26, the Arbatel also suggests “that each one may recognize their guardian spirit, and that he obeys him as if it were the word of God” (2009, 55). As side-prerequisites, the Arbatel also mentions being secretive regarding the art (aphorism 1 and 39), “liv[ing] for yourself and for the Muses,” not mingling too much with others, being “beneficent to all people,” being “diligent in your vocation” (aphorism 3, 2009, 13), and “support[ing] nothing which is wicked, unfair, or unjust, or even entertain such thoughts” (aphorism 39, 2009, 81).

If these prerequisites are met, the Arbatel frequently asserts that “there is nothing that your soul will desire that will not be granted in the future” (aphorism 5, 2009, 15), that “EVERYTHING WILL COME TO A HAPPY AND DESIRED OUTCOME” (aphorism 15, 2009, 29), or, even more promisingly, that “YOU WILL RECEIVE WHATEVER YOU HAVE ASKED FOR” (aphorism 11, 2009, 21). The text is so straightforward with regard to what appears to be blatant wish-fulfilment through Christian faith and prayer alone (further instances: “All things are possible to those who believe and are willing,” aphorism 20, (2009), 43; “whoever incites passionate prayer for what he desires, will not suffer rejection,” aphorism 28, (2009), 63) that it reminds the attentive reader of the modern New Thought Movement. Is there a chance that Phineas Quimby or Emma Curtis Hopkins read the Arbatel? Whatever the case, no further preparatory steps are specified in the Arbatel, with such typical ‘Solomonic’ practices as fasting, washing, or austerity completely absent.

The second step involves the practitioner deciding upon his ritual goal and identifying the corresponding spirit. ARATRON (Saturn), for instance, “turns treasures into coal, and coal back into treasure […] He gives familiars with definite power […] He makes one invisible […]”; BETHOR (Jupiter) “exposes treasures, and secures the cooperation with aerial spirits […] and provide[s] medicines which are miraculous in their effects” (aphorism 17, 2009, 31–33). Irritatingly, the Arbatel provides a second list in aphorism 24, in which 21 so-called “secrets”—ritual goals in my analytical terminology—are divided into three categories: “greatest secrets” (which include healing, longevity, and “To know God and Christ,” 2009, 49), “medium secrets” (such as the transmutation of metals, natural magic, prophetic visions), and “lesser secrets” (e.g., acquiring wealth, exceling in military matters, or being “a good theologian […] educated in all writers of theology, ancient and modern,” 2009, 51). Aphorism 27 provides a graphical tool, namely a circle with 112 spokes (divisions), with four primary divisions based on the cardinal directions. These are said to help one to determine one’s wishes (or ‘secrets’) and to relate them to the corresponding spirits. However, no further instructions are given regarding the use of this circle, apart from the hint that the spirits responsible for the “greatest secrets” should be invoked while facing towards the East, the spirits of the “medium secrets” while facing towards the South, and the spirits of the “lesser secrets” while facing towards the West and North.31 It seems to me that the author has amalgamated two different sources here—one list of goals ascribed to the Olympian spirits, and another list of 21 goals mapped onto a circle and ascribed to the cardinal directions—which do not fit together properly. The goals ascribed to the Olympian spirits also do not correspond to the goals mentioned in the ‘secrets’ aphorism. However, it is most likely that the intention was for the practitioner to first choose a goal, then look for its cardinal direction in the circle, and then for its corresponding Olympian spirit or sub-spirit.

In the third step, the practitioner identifies the name of the spirit which corresponds to the chosen ritual goal or ‘secret.’ There are, of course, the names of the seven Olympic spirits—who “inhabit the firmament and the stars of the firmament, and their duty is to decide fate, and to administer accidents of fate, inasmuch as God agrees and permits” (aphorism 15, 2009, 27–29)—each of which may be evoked directly.32 However, the practitioner may also, voluntarily or involuntarily, conjure subordinate spirits ascribed to the “governors or different offices of the Olympians” (aphorism 16, 2009, 29). The Arbatel thus specifies the number of ‘offices’ that each Olympic spirit controls (e.g., ARATRON: 49; BETHOR: 42; etc.) and numerous subordinate spirits that reside in these ‘offices’ (e.g., ARATRON: “49 kings, 42 princes, 35 governors, 28 dukes, 21 attendants standing before him, 14 servants, 7 messengers: He commands 36000 legions; a legion numbers 490,” 2009, 33). In fact, “with average magi, the governors will send some of their spirits, who will obey within certain limits” (aphorism 17, 2009, 39). The practitioner may also consciously decide to address a subordinate spirit: “if you covet a lesser office or dignity, magically summon the subordinate of the prince, and your request will be granted” (aphorism 32, 2009, 69).

As mentioned previously, the names of these subordinate spirits are not provided in the text, and we may assume that they are delivered by the guardian or assistant spirit that one has invoked previously.33 The beginner is, however, recommended to “operate without names, but only with the offices of the spirits” (2009, 41–43) and then await further revelations or divine instructions. Indeed, spirits are so crucial to the Arbatel that they determine its very definition of the ‘magician’: “The magus is, for us, one to whom the spiritual essences serve to reveal the knowledge of the whole world and of nature, whether visible or invisible, through divine grace. This definition of the magus applies broadly, and is universal” (aphorism 41, 2009, 85).

Alongside the spirit’s name, the practitioner observes the correct cardinal direction in which the spirit is to be conjured, the correct timeframe (i.e., when they preside, probably on one of the seven days of the week, and preferably during the first hour after sunrise: see aphorism 21), and prepares the respective sigil that is ascribed to the corresponding Olympian spirit (named ‘CHARACTER’ throughout the text). In contrast to contemporaneous texts of learned magic dedicated to the Solomonic art of conjuring spirits, the Arbatel does not properly explain how to actually use the sigil during the conjuration (e.g., by wearing it on the body, holding it in one’s hand, or placing it somewhere).

The description of the fourth step, the conjuration itself, is surprisingly short and simple. The location for the rite is not even specified. No ritual circle needs to be drawn on the ground, and no fabrication of further ritual tools and devices (such as a special cloth, wands, swords and daggers, a trumpet, pens, inks, and paper, etc., as in the case of the Clavicula Salomonis) is required. The invocation reads as follows (aphorism 21):

O GOD ALMIGHTY AND ETERNAL, you who have established all of creation for your praise and honor, and the service of mankind, I beg you to send your SPIRIT N.N. of the solar order, to inform and teach me the things I have asked (or, that disclose to me the cure for edema, etc.), but may your will, not mine be done, through JESUS CHRIST your only begotten son, OUR LORD. Amen. (Peterson 2009, 45)

There are no fumigations involved, no sacrifices, and no recitations of voces magicae.

In the fifth step, the Arbatel recommends that the practitioner “not detain the spirit beyond one hour” (ibid.). The following formula is provided for the dismissal:

BECAUSE YOU CAME PEACEFULLY AND QUIETLY, and answered my petitions, I give thanks TO GOD in whose name you have come, and may you go now in peace to your order, returning to me when I call you by your name, or order, or office, which is permitted by the Creator. Amen. (ibid.)

All in all, the Arbatel reads like a trimmed version of the Clavicula Salomonis, or one of the related early modern ritual texts dedicated to the art of conjuring spirits, that has been heavily simplified (with regard to its ritual complexity) and at the same time made far more pious (with regard to its overflowing theological and biblical lip service). In a way, the author’s background intention may have been the same as that of John of Morigny who, a few centuries earlier, fabricated his own version of the contested Ars notoria ritual in his Flowers of heavenly teaching. As Claire Fanger has demonstrated, John’s attempt to circumvent theological condemnations of his ritual practice by exchanging the dubious notae with worship acts dedicated to the Virgin Mary failed dramatically (the book was publicly burnt in 1323: see Fanger 2015, 2021). We have no further evidence of the intention or fate of the author of the Arbatel, but the pattern seems both fairly similar and also similarly unsuccessful, at least with regard to various later ‘crimen magiae’ trials in which the possession of copies of the Arbatel was not particularly conducive to the longevity of their owners.34

Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience

As mentioned at the outset of this article, Frater Acher claims to have conjured six of the seven planetary spirits35 mentioned in the Arbatel between the years 2010 and 2013, i.e., shortly after having finished 10 years of daily training in magic(k) and having passed through his graduation at I.M.B.O.L.C. (in 2009). What may seem like an unusual choice at first glance becomes less surprising if we quickly browse through the internet, for the Arbatel seems to be a rather popular ritual script among contemporary practitioners of magic(k). There is a (private) Facebook group named “Arbatel & Olympic Spirits Grimoire Magic Group” with currently no fewer than 3.006 members.36 The word “Arbatel” currently (February 20, 2023) prompts ca. 113.000 hits on google, and there are hundreds of videos on youtube.com dedicated to the text, the most watched of which has more than 253.000 views.37 Limited deluxe goat leather editions of the Arbatel go over the counter to the true aficionado for $450.38 If we search for “Arbatel amulet” or “Arbatel talisman,” we encounter a large number of commercial vendors of neat golden or silver emblems with inscriptions of the Arbatel’s spirit names and their sigils.39 There are numerous further blogs and websites providing experience reports and suggestions with regard to practicing the Arbatel. As a contemporary practitioner of magic(k), it thus seems almost impossible to overlook the text. Despite this plenitude, Frater Acher’s Arbatel experiences are analysed here because they are by some margin the most detailed, elaborate, and self-reflective accounts that have so far been made publicly available by a contemporary practitioner.

Re-interpreting the Arbatel

Given that modern practitioners have sigil magic(k) and sex magic(k) (or combinations of the two) at their disposal—two extremely simple ritual techniques that take little time yet are nonetheless highly effective, according to many practitioners—why bother spending months or even years to conjure planetary spirits by following a centuries-old script? Frater Acher’s explanations are helpful when it comes to answering this question. In the introductory part of his “The Arbatel experience” website, he outlines the advantages and risks offered by the wide availability of premodern manuals of learned magic on the internet. In particular, he points to what he sees as a common misunderstanding:

There is another, much more rarely talked about aspect that is troublesome. Some of the magical grimoires - and the Arbatel certainly is one of them - actually can be utilised as self-initiatory systems and might have even been conceived as such. […] It seems the tradition and art to bring to life such initiatory aspects of the grimoires has almost been lost entirely. Instead it has been replaced by a surface—maintained both online and in print—that makes these books seem like another shortcut towards instant gratification. Something that of course blends well with the spirit of our time.40

Frater Acher goes on to explain that he—and an unnamed friend—decided in 2009 to practice the Arbatel not for its promise of “instant gratification” (i.e., short-term inner-worldly wish-fulfilment), but, rather, precisely as a ritual tool contributing to the spiritual ascension of the practitioner: “We believed that the Arbatel presents a highly practical system that allows the practitioner to ascend on the Hermetic ladder—through each planet’s phase—all the way from Malkuth to Binah.41 Testing this assumption was the goal of our work and we were willing to pay the related price for it” (ibid.). Frater Acher goes on to compare this interpretation of the Arbatel with a practice that had already been performed by members of the Golden Dawn and, in particular, Aleister Crowley, a type of astral projection known as ‘rising on the planes’:

What we have here are two pretty different magical techniques that still aim towards similar ends. The Rising on the Planes elevates the astral body of the practitioner above Earth and then onwards through the seven planetary realms. That is, it pulls the astral energy of the magician upwards into higher realms. The ritual cycle of the Arbatel takes the opposite approach with a similar goal—it opens gateways of planetary forces into the material realm and pulls down their energies one after the other to be grounded within Earth and the physical body of the practitioner. The major difference between the two thus is that the first exercise predominantly works on the astral plane, whereas the latter aims to bring down the planetary forces through all planes and into the material realm.42

Accordingly, Frater Acher considers the Arbatel to be a “method to cathartically re-balance and reintegrate the planetary forces into one’s own psyche, subconscious mind and magical art” (ibid.).

This description nicely illustrates a significant shift of interpretation that happened in the history of Western learned magic from the nineteenth century onwards. As I have shown elsewhere, practitioners at that time tended to devalue the short-term inner-worldly ritual goals that pervaded the premodern literature, and instead began to re-interpret the practice of magic(k) as a tool for personal transformation, spiritual ascension, and self-deification or apotheosis (a process that was fully sparked with the workings of the Golden Dawn, see Otto 2018b, 88–89). The oft-evoked terminology used to describe the practice which aimed at this new goal—the shift being from optimising the outer circumstances of life to perfecting the inner self—was ‘theurgy’ or ‘higher magic.’ Even though there are, as we have seen, no traces of methods in the original Arbatel for rising up the ‘Hermetic ladder’ or the Sephirot of the kabbalistic tree of life, this is exactly how Frater Acher and his ritual partner re-interpreted the text in 2010.

This re-interpretation is mirrored by Frater Acher’s basic motivation for actually conjuring planetary spirits and figuring out what to ‘do’ with them. As we have seen, the Arbatel’s ritual logic is entirely based on choosing a specific (usually short-term, inner-worldly, i.e., purely instrumental) ritual goal and then conjuring the corresponding spirit, who will, the text suggests, quickly fulfil one’s wish or ‘secret’. Frater Acher’s motivation was different, as he explains in the ritual diary that outlines the first invocation of PHUL (moon):

Let me briefly talk about my personal attitude and intention for the acts(s). It was important to me that the successful communion with the respective Olympic Spirit should be the only goal of the rites. Rather than performing the rituals for reasons of personal material gain or spiritual support, my focus should be entirely on understanding the nature of the Olympic Spirits themselves.43

Accordingly, as Frater Acher points out in his OCH diary, his main motivation to conjure a planetary spirit was to “be in his presence for a short while, experience his energy, his qualities and learn about his influence on myself and the world in general.”44 In other words, Acher’s Arbatel practice functioned as an experimental “exploration into the nature of the Olympic Spirits through questions and answers.“45 Taking Acher’s interpretation of the Olympic spirits into account, we can understand that he intended to tap into those basic forces that “create creation itself” and that are hence to be considered more powerful than other intermediary beings such as demons or angels, as he claims retrospectively while pondering the risks and necessities of his practice.46 Interestingly, thus, Acher does not ‘psychologise’ planetary spirits which for him are external entities, due to his ‘traditionalist’ self-understanding as a learned magician. Yet, his aforementioned re-interpretation of the Arbatel as a “method to cathartically re-balance and reintegrate the planetary forces into one’s own psyche, subconscious mind and magical art”47 represents a typically modern strategy of psychologising magic(k) (on this strategy see, among others, Hanegraaff 2003; Asprem 2008; Pasi 2011; or Plaisance 2015) and of using its techniques for quasi-therapeutic and/or self-growth purposes (see on this motif especially Luhrmann 1989, 244–45, 279–80, 287–88).

Re-designing the Ritual Choreography

Alongside this fundamental re-interpretation of the original text, Frater Acher and his ritual partner developed a ritual choreography for conjuring the Olympic spirits that differs markedly from the procedure outlined in the original text. The reason is that, from their perspective, “the actual ritual structure that is supposed to frame the Arbatel prayers” was rather obscure and they thus had to “fill in these blank spots ourselves.”48 They assumed that there existed a missing part of the Arbatel that outlined “instructions on how to actually summon the Olympic Spirits in a ritual setting rather than purely praying for their appearance” (ibid.).49 With this in mind, they developed a ritual choreography that was predominantly oriented towards ritual procedures from the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (the main source of inspiration of Acher’s teacher Agrippa) and hence towards ritual scripts that rather belong to the Solomonic tradition—as these had partly informed the Golden Dawn—50 than to the Arbatel itself (in contrast to the mindset originally underlying the Arbatel, as we have seen above). Accordingly, they chose “the Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram together with a slightly adjusted version of the Ritual of the Hexagram as frame rituals”, and came up with the following basic design for the conjuration of PHUL (Moon):

- Kabbalistic Cross

- Lesser Banishing ritual of the Pentagram

- Welcoming of God in the four quarters of the circle

- Adjusted Hexagram ritual of the Moon

- Gesture of the opening of the veil

- Arbatel prayer for protection of God and consecration of Table of Practice (from Second Septenary, Aphorism 14)

- Arbatel evocation of Phul (from Third Septenary, Aphorism 21)

- Communion with Phul

- Gesture of the closing of the veil

- Lesser Banishing ritual of the Pentagram

- Ritual license to depart. (Ibid.)

Connoisseurs of Golden Dawn rituals will be sure to recognise that most of these ritual elements are derived from the Golden Dawn current, whereas only two prayers are taken from the Arbatel itself.51 Acher in fact concedes that the structure is inspired by previous conjurations of planetary spirits which “had been set up and conducted according to the classic Golden Dawn approach and expanded with more recent techniques for solitary practitioners by my previous teacher or myself.”52 What is more, in contrast to these previous conjurations, which had been invocations (“i.e. I used my body and consciousness as a vessel for the planetary influence and then acted as a personification of the respective divine principle”), Acher and his ritual partner decided that the Arbatel rituals should be of “evocative nature”—they hence fabricated “a version of Trithemius’ Table of Practice as the ‘locus of manifestation’ for the spirits” (ibid.). Acher provides a detailed script for the production of this device—which is essentially a black mirror on a wooden table—on his website (see figure 1).53

During the Arbatel conjurations, Frater Acher installed this mirror in the ritual chamber that he had built into an old barn close to his house, which is situated in a small Bavarian town.54 The mirror was placed on the altar in the middle of a ritual circle (see figure 2), and the evoked planetary spirits were thus meant to ‘appear’ in or above said mirror.

Frater Acher’s and his partner’s ritual choreography for the Arbatel included a few further elements that are not provided in the original text. One concerns purification rites that, as we have seen, are not prescribed in the Arbatel. Nevertheless, Frater Acher’s training demanded various preparatory rites such as “Continued abstinence of meat, alcohol and cigarettes since the beginning of the Arbatel operation,” “consciously focussing on the forthcoming ritual during every day of that week,” “Dedicating the full day of the operation to the work, including several hours of preparatory work (e.g., creating the Lamen) and meditation,” as well as “Ritual cleansing, bath and meditation before the performance of the rite” (ibid.).55 To Acher, these preparations are key to being “able to alter your state of consciousness in order to break through or avoid perceptive filters which normally inhibit direct experience of and communion with spirits” (ibid.). The same goes for the use of various ‘paraphernalia,’ as Frater Acher calls the items used in the ritual, namely a self-made robe, crown, belt, ring, dagger, and sword. Again, the ritual framework here is the Solomonic art of conjuring spirits as handed down via the Golden Dawn tradition, and then interpreted from a personal and contemporary perspective.56

Another important deviation from the original script is the great importance of imagination techniques in Frater Acher’s practice. These techniques are not only used during the ‘communion’ with the Olympic spirits themselves. In his records of the rituals, Acher usually describes what he ‘sees’ with closed eyes. A nice example of this type of what he calls “inner spirit contact” is his description of PHALEG (Mars):

When I felt stable in my magical trance, I closed my eyes and looked upwards. Only at this moment did I realize that the moon had descended right into my circle. It hung over my head like a huge silver cloud. Had I raised my hand I could have touched the round belly of the moon. The entire circle under my closed eyes was filled with silver light.57

In Frater Acher’s Arbatel experiences, imagination techniques are also involved during the various sub-rituals that are derived from the Golden Dawn. For instance, Acher performs the pentagram and hexagram rituals not only physically, i.e., in his ritual chamber, but simultaneously also in his mind through imagination.58 Acher here draws inspiration from the German practitioner Franz Bardon (1909–1958) and his Praxis der magischen Evokation (1956), aiming to create within the ritual circle a ‘vacuum-like’ space that resembles the characteristics of the evoked spirit, for instance through visualising its colors, so that it will be willing to appear and will feel most comfortable.59 The relevance of imagination techniques for Acher’s Arbatel experience became more crucial over time, as he became acquainted with Josephine McCarthy and her concept of ‘visionary magic(k)’ only after the fourth conjuration. As a consequence, the description of the last conjuration of BETHOR, in particular, reads quite differently from those that precede it, as Frater Acher here systematically differentiates between the ‘inner realm’ and the ‘outer realm’ and stresses that it is necessary “to be present in both realms at the same time—inside and outside.”60 Acher thus engages in interesting re-interpretations of his previous practice and the necessity of performing the ‘outer’ rituals at all.61 Today, he claims that the experienced practitioner may produce the same effect with much less ritual effort.62

Frater Acher’s Experimental Approach

This last observation—that Acher continuously changed his ritual procedures and interpretations over the course of the Arbatel conjurations—is crucial for understanding his overall approach. It shows that even traditionalist magic(k), with its lengthy ritual scripts, its multitudinous rules and paraphernalia, and its alleged ritual formalism, is nothing but an experimental enterprise for the practitioner—an enterprise that necessitates open-mindedness, ongoing re-calibration, and creativity (on experimental creativity as a common trait in modern magic(k), see also Luhrmann 1989, e.g., 69-70, 120).

We can see this in, for instance, Acher’s amendment of an additional conjuration formula—taken from a late ancient ritual text, namely PGM IV—before the second conjuration of OPHIEL;63 his change of time-frames before the third conjuration of HAGITH;64 his ‘deep learning’ that consists in properly preparing the ritual site after it has been occupied by physical and ‘astral’ cobwebs;65 his on-going reflections on his spiritual encounters and how they might actually have worked;66 his omission of basic prayers before the fifth conjuration of PHALEG, which he deemed unnecessary or even as hindering the ritual at that point,67 and thus his reflections on how far he actually differs from the Renaissance practitioner;68 and finally, his much more systematic implementation of ‘visionary magic(k)’ during and after the conjuration of OCH.69 Acher’s ritual diaries thus demonstrate that even the use of a seemingly straight-forward and easy-to-use ritual template such as the Arbatel calls for ongoing creativity and innovation.

Acher’s experimental approach is, of course, most visible in his self-proclaimed ‘encounters’ with the Olympic spirits. During these encounters or, in his tongue, ‘communions,’ Acher seems to have followed two different strategies. First, he engaged in what he calls ‘immersion,’ a process through which he identified with the respective spirit in his mind and body. A good example of this type of experience is found in his description of PHALEG (Mars):

And through my being, through the substance I turned into roams the presence, the electrical current of Phaleg. His forces swirl and dance through my expanded consciousness and body like invisible currents through water, like wind through the skies. He is weightless, yet full of living force. If I ever encountered a spirit smiling or in a happy state it is right now. I continue to sing Phaleg’s name and allow his electrical currents to fill everything with vibrant life. All my body has turned into organic, Venusian matter just to balance his immense power.70

During the actual ‘communion,’ i.e., the evocation of the spirits into or onto the black mirror, Acher attempted to ‘receive’ their respective shapes and secret names, in addition to any further information that they were willing to share with him. Hence, all six ritual diaries provide a drawing of the spirit (see figure 3 for the spirit of OCH as an example), a specification of their secret names, and an ‘interview’ that Acher conducted with the spirit during the evocation.71

Repercussions

Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience had a range of more or less significant repercussions on his private life, according to his own narrative. These included long-term effects of the practice which extended beyond Acher’s primary goal to be in the spirit’s “presence for a short while, experience his energy, his qualities and learn about his influence on myself and the world in general.”73 As mentioned at the outset of this article, Frater Acher re-interpreted the Arbatel as a “method to cathartically re-balance and reintegrate the planetary forces into one’s own psyche, subconscious mind and magical art” (ibid.). In fact, Acher is convinced that “any successful spirit communion will express itself in changes in our lives […] The forces of the spirit we work with will take shape and merge into our personality as soon as we allow them to sink into our subconsciousness and become one with who we are underneath our skins.”74 So, what were the long-term effects of Acher’s Arbatel experience, according to his own narrative?

On the one hand, he regularly hints at the repercussions of his communication with a given planetary spirit in his private life, albeit without going into great detail.75 For instance, after the conjuration of HAGITH (Venus), he writes:

One of the most interesting results was physical illness which stemmed from an overload with Hagith’s (i.e. Venusian) energies which again led to a breakthrough of the barriers that I had built around these in my body and mind. As a result Hagith’s qualities became much more predominant—or I should say balanced—in my life since then. The aspects of ‘love as a tool that opens and life as the seed that follows’ established itself as the central theme in my work, private and magical life for several months. Essentially that period lasted for three months, from March until May 2011.76

While this sounds like a rather pleasant experience (physical illness aside), Acher also underwent a severe crisis after the conjuration of OCH (sun). In a blog post entitled “the beast that almost got me,” he concedes that as “a human we are not made to live in the Sun, but to live in its orbit. We are not meant to be the centre of our own universe—but to circle around it in spheres.”77 He goes on to imply that OCH in fact had a rather destructive impact on his life: “Every other life, every other career, every other relationship will suddenly seem in reach. The power to re-imagine and start afresh will be abundant and the ease to destroy what we have built uncannily alluring” (ibid.). Accordingly, he warns the reader that after identifying with the sun itself, “Ego and hunger will be infinite.”78

This corresponds to Acher’s general warnings regarding the practice of the Arbatel. All in all, it does not seem to have been a purely healthy and benign practice. Acher frequently mentions severe exhaustion, particularly after the conjurations.79 In later sections of the conjuration series (from HAGITH onwards), and particularly in texts written in the aftermath, he thus takes a critical perspective towards the entire practice:

The Olympic spirits are not meant to be present in the physical realm unfiltered. They are forces beyond the world of creation that manifested on this planet. Calling them down unfiltered, establishing a physical space for them on earth was a very dangerous act that easily could impact and unbalance creation around it. This was true for their impact on the inner as well as the outer realm; in both realms performing this rite meant for these spirits and their forces to enter a space they weren’t meant to be in. Equally the space they were called into wasn’t intended to hold such capacities of immediate power.80

In a similar vein, Frater Acher claims that it “is because of the nature of these spirits why the mage should never try to manipulate them. In fact it is advisable not to work directly with these spirits at all” (ibid.). He ponders self-critically whether he may have barked up the wrong tree in the first place and concludes with the telling words: “When the magician brings down the Olympic spirits into their temples it should be for one reason only: to enlighten their own mind with better understanding of how this world works. And then to get out alive again” (ibid.).

As of today, Frater Acher has not yet practiced the seventh conjuration, that of ARATRON (Saturn). In an email communication from November 11, 2018, he concedes that the practice of the Arbatel, as well as his further practice of magic(k), had such severe consequences that he has hitherto refrained from the final conjuration of the Saturn-spirit (which, given Saturn’s astrological reputation, might also be the most efficacious yet challenging one).81 What is more, in 2013, i.e., shortly after the conjuration of BETHOR (Jupiter), Acher had several critical and life-changing experiences while practicing other types of magic(k), as a result of which he “almost lost my job as well as the wonderful relationship to my wife.”82 Most importantly, he also became severely ill. In hindsight, Acher ascribed this disease to his practice of magic(k) and decided to reduce his commitment for some time.83 However, he also suggests that he did not forget ARATRON and will eventually complete the cycle, as soon as he “gets around to doing it” (ibid.).

Conclusions (or: Why Conjure Planetary Spirits in the Twenty-First Century?)

Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience is perfectly suited as an illustration of this special issue’s overall topic: ‘Western learned magic as an entangled tradition.’ We have here a ritual script—the Arbatel—that was first printed in Basel in 1575, but whose foundational idea can be traced back to the Arabic-Islamicate realm of the eighth century CE. At the time of the Arbatel’s composition, the author picked up this idea—that it is possible and indeed promising to conjure spirits ascribed to the seven ‘wandering stars’ of Ptolemaic astrology—and disguised it with over 70 biblical quotations, adopting in parallel further textual-ritual patterns from both the humanist-Paracelsian discourse on ‘magia naturalis’ and the Solomonic art of conjuring spirits. In other words, the original text already attests various types of religious and ritual hybridity and thus outlines a highly ‘entangled ritual,’ characteristics that are, however, typical of the tradition of Western learned magic at large.

Over the course of the following centuries, the text was repeatedly transmitted, re-edited, and translated, ultimately becoming a much-discussed ‘classical’ script of learned magic in practitioner discourses of the twentieth and twebty-first centuries. Yet, we know little of its practical applications. Was it, in premodern times, ever practiced in the way outlined in the text? Or was it rather an early modern fantasy novel in the shape of a ritual script? That we are not able to answer such questions—due to the notorious lack of trustworthy premodern ego-documents—is one of the fundamental methodological difficulties we face in the study of large parts of Western learned magic. Premodern ritual texts, even though vivid and fascinating, thus appear ‘dead’ to the modern scholar.

However, as this article seeks to demonstrate, it may be both worthwhile and interesting—from a historical as well as an analytical perspective—to tap into the experiences of contemporary practitioners of magic(k) who appropriate these texts. There is a wealth of hitherto neglected experience reports authored by modern practitioners of magic(k) who have—much like experimental archaeologists—given these texts a trial run and described how one might actually succeed in practicing a premodern ritual script such as the Arbatel. However, we have also seen that for a contemporary practitioner of magic(k) such as Frater Acher, such an undertaking is anything but quick and easy. Such a months- or years-long process is no mere fascination-driven self-entertainment, nor is it an effort- and riskless ‘exploration into the spirit realm.’ It requires significant amounts of training, time, resources, and creativity. Even more importantly, for someone who believes that the spirits outlined in such texts actually exist and thus possess the power and efficacy ascribed to them, it will also be a dangerous enterprise that requires commitment, courage, and respect: “In magic, like in many performing arts, the practitioner themselves is the only safety net [sic].”84 It is precisely this belief that may legitimise the analytical comparison of modern and premodern practitioners of learned magic—assuming that premodern practitioners are likely to share this belief (even if they would typically have considered God to be their ‘safety net’)—and thus encourage scholars to take into account contemporary experience reports more systematically in the study of Western learned magic.

However, even if we consider such experience reports to provide legitimate data for the academic study of Western learned magic, we must, of course, take into account the wide array of cultural adaptations, theoretical re-interpretations, ritual re-configurations, and ongoing innovations that underlie these reports. Undoubtedly, the practice of the Arbatel in the twenty-first century will differ significantly from its premodern application. This difference relates to a second type of ritual entanglement that does not concern the text itself but rather the ever-changing mindset, intention, and creativity of its practitioners. In the case of Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience, we have seen that this second type of ritual entanglement—which arises during the practical application of a ritual script—can be at least similarly extensive. Like many other ritual scripts in the history of Western learned magic, the Arbatel can thus be interpreted as a ‘living’ text in two senses of the word: It attests to changeability and textual-ritual entanglements not only on the level of the text itself and its century-long transmission history, but also on the level of its practical application and creative adaptation to ever-changing cultural and religious circumstances, worldviews, and mindsets.

As we have seen, Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience merges (1) a late ancient conjuration formula from the Greek Magical Papyri, (2) the Arabic-Islamicate (ultimately Sabian) art of conjuring planetary spirits, (3) late medieval and early modern ritual techniques for conjuring spirits taken from Solomonic grimoires, (5) early modern Paracelsian motifs and ideas, (6) Christianate prayer patterns taken from the Arbatel, (7) the notion of the spiritual ascension of the magician, here interpreted as a ‘hermetic’ ascent through planetary spheres, (8) various ritual techniques taken from the Golden Dawn current (e.g., the lesser banishing pentagram ritual), (9) imagination techniques taken from twentieth and twenty-first-century authors such as Franz Bardon and Josephine McCarthy, (10) an emphasis on ritual ‘gnosis’ (trance) which might be inspired by modern Chaos magic(k) literature, (11) a strong focus on self-transformation and psycho-spiritual maturation through magic(k), and, finally, (12) a rather ‘mystical’ striving towards temporary communion with planetary spirits.

Frater Acher’s Arbatel experience, even though inspired by the original script, thus points to the construction of an entirely novel, unprecedented, and highly innovative ritual series—in stark contrast to his ‘traditionalist’ self-understanding. Even though Western learned magic has always been subject to all sorts of chrono- and geographical entanglements and thus tended to produce strikingly ‘entangled rituals,’ we might consider Frater Acher’s interweaving of such a large number of ritual techniques and motifs from the past two millennia as a particularly noteworthy illustration of this overall tendency. Acher’s Arbatel experience thus provides a perfect illustration for the argument outlined at the beginning of this paper, namely that it is misleading to “squeeze contemporary magic(k) into established categories of the study of religion, and thus look at it in the sense of ‘contemporary esotericism’ or a ‘new religious movement’.” It is in fact much more reasonable to interpret contemporary magic(k) as being part and parcel of the longue durée textual-ritual tradition of Western learned magic, and thus to analyse contemporary texts and techniques of magic(k) against the backdrop of their manifold inspiring sources, which may go as far back as late ancient Egypt.

Does Acher’s Arbatel experience illustrate a significant rise of ritual entanglements in modern magic(k)—eventually sparked by the internet era, which has facilitated access to and the combination of a large number of ritual scripts and techniques from premodern centuries? Certainly: from reading premodern grimoires, particularly from the Solomonic cycle, we get the impression that learned magic in those centuries was a rather formalistic enterprise: following the script seems to have been of utmost importance. However, this impression might be misleading due to an apparent lack of trustworthy experience reports and ego-documents from those centuries. Instead, it may be more reasonable to assume that oscillating between a formalist-traditional and a creative-innovative approach towards the ritual art may always have been a reasonable, if not necessary, strategy—say, in order to cope with opaque passages or gaps in the script, to make pragmatic decisions in the case of differing ritual templates, or to heighten one’s ritual efficacy after repeated failure. Seen from this perspective, the striking heterogeneity and volatility even among outwardly ‘similar’ manuscripts of the Leipzig ‘Cod. Mag.’ collection (see Bellingradt and Otto 2017) might point to such a strategy of oscillation, wherever deemed necessary, thus bearing witness to a significant degree of creativity and innovation among premodern practitioners of learned magic as well. However, the apparent heterogeneity and volatility in premodern manuscript-based learned magic may have been overlooked or suppressed from the nineteenth century onwards, when some select (few) manuscripts became ‘standardised’ through printed text editions or translations (e.g., those published by members of the Golden Dawn).