The Meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in Ancient Greek Texts: A Quantitative Approach Using Computer-Driven Methods and Tools

This article analyzes the use and meaning of central Greek terms related to images in ancient Greek texts collected in the Diorisis Ancient Greek Corpus (Alessandro Vatri and McGillivray 2018). In contrast to the existing literature on the (religious) status of images in Greco-Roman Antiquity, Judaism, and Christianity, this article applies a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and computer-driven examinations with a qualitative analysis of selected sentences. The examination of the use and meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn considers various religious contexts (Jewish and Christian as well as Greco-Roman polytheistic), thereby embedding this article in the larger framework of comparative religious research on synchronic inter-religious contact.

an/iconism, terminology, Ancient Greek Religion, corpus linguistics, digital humanities, Christianity, Judaism

Introduction

The goal of this article is to analyze the use and meaning of central Greek terms related to images1 in ancient Greek texts. Different from the existing literature on the (religious) use and meaning of images in Greco-Roman Antiquity and Judaism/Christianity,2 this article applies a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and computer-driven examinations with a qualitative analysis of selected sentences.3

The examination of the use and meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn considers various religious contexts (Jewish and Christian vs. Greco-Roman polytheism), thereby embedding this article in the larger framework of comparative religious research on synchronic inter-religious contact.4 In this context, special attention is paid to the “relatedness to matter and media in [the] material aspects [of images]” (see the introduction of this special issue) and the differences (and similarities) between the Greco(-Roman) and the Jewish and Christian relations towards images. These two research foci and the corresponding analyses will hopefully shed new light on the overarching topic of an-iconic, anti-iconic, and iconic attitudes of religions towards images.

The data basis of this inquiry consists of the Diorisis Ancient Greek Corpus (Vatri and McGillivray 2018a, 2018b) that includes over 820 Greek texts from the eighth century BCE to late Antiquity (approximately fifth century CE). The texts in the Diorisis corpus are analyzed in this article using Python scripts and existing software solutions from the field of corpus linguistics (particularly LancsBox, see Brezina, Weill-Tessier, and McEnery 2020; 2018). To account for the comparative interest of this article, the 820 texts in the Diorisis corpus are split into two subcorpora according to their religious affiliation (Jewish and Christian texts and Greco-Roman polytheistic texts).

The methods applied during the examination of the distribution, use, and meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in Jewish, Christian, and Greco-Roman polytheistic texts include:

- The quantitative analysis of the absolute and relative frequencies of the lemmas5 of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in both subcorpora (Jewish and Christian vs. Greco-Roman polytheistic).

- The quantitative analysis of the absolute and relative frequencies of different types6 of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in both subcorpora. This builds an important addition to the previous analysis of lemmas since it enables the study of the distribution of different cases (for instance, if a specific term is mostly used in the genitive plural, etc.).

- The collocation analysis of the lemmas of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in both subcorpora.

- The analysis of the word vectors (Word2Vec) of the lemmas in both subcorpora.

- The qualitative analysis of selected sentences from the above-mentioned quantitative analyses.

Before starting with the analysis of the respective terms, I will first provide a short overview of the current research on the use and meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn.

The Use and Meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in Current Research

The terms agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn have been selected among many other potential terms (such as andrias, stêlê, ksoanon, bretas, etc.) because they are the ideal candidates for a comparative analysis of the Jewish, Christian, and Greco-Roman polytheistic use of terms related to images. All three terms are not only frequently found in both subcorpora but are also extensively used in inter-religious polemics between Jews, Christians, and pagans (see Said 1987). Eidôlon is often pejoratively applied in Christian texts when referring to non-Christian deities and their material representations. Eikôn is the central Christian term for accepted Christian images, not least during the image struggles in the Byzantine Empire between the eighth and ninth centuries CE (see Brubaker and Haldon 2011). Furthermore, the eikôn also has a long (intellectual) history in Greco-Roman Antiquity. Agalma is a term often applied in Greco-Roman polytheistic texts to signify (divine) statues of great value in temples and is less frequently used in Jewish and Christian texts, thereby rendering it an interesting example of a more ‘exclusive’ terminology of images that is later dropped in favor of other expressions.

In the following parts, all three terms will be introduced in more detail.

eidôlon

The term eidôlon is etymologically related to eid-, eidos (lit. “that what is seen,” shape) and conveys the notion of visibility (see Said 1987, 310). Eidôlon typically denotes a likeness of the surface or of the material form of an object, almost like a ghost or phantom (see Od. 11, 476), but it can also be used more broadly for a statue (see the golden statue of a woman, γυναικὸς εἴδωλον χρύσεον [gynaikos eidôlon chryseon], in Herodotus 1, 517). Eidôlon and eikôn both have a long and rich history in Platonism (and other philosophical traditions) (see Kunz, n.d.; Meyer-Schwelling, n.d.; Donohue, n.d.). In Platonism, an eidôlon represents the artificial imitation of the visible appearance of something, thereby pointing to its surface and not its real being (which already conveys a rather negative associative context in the sense of a trompe-l’œil, see Said 1987, 326–27; Steiner 2001, 5).

In a Christian context, the delusive character of an eidôlon already found in certain Greco-Roman polytheistic philosophical traditions is maintained, and the term eidôlon becomes the central term to pejoratively denote pagan (divine) images and their worship (eidô(lo)latria, see Tertullian, De idololatria). This ambiguous or even negative association of an eidôlon is perceivable until today, for instance in the English term “idol” or German Idol (particularly with worship: ‘idolatry’).8

eikôn

Just like eidôlon, the term eikôn signifies an appearance/representation resembling something else. However, eikôn has the connotation of a more general (symbolic) resemblance (see the adjective eikelos meaning “like” in a more symbolic or metaphorical sense)9. The eikôn can also signify a concrete object, such as a statue. However, the term eikôn is more sophisticated in the sense of a likeness of something that does not necessarily need to have a visible shape or material form (eikôn tinos), for example the Platonic ideas (see again Meyer-Schwelling, n.d.; Horn, Müller, and Söder 2017, 219, 227). The eikôn—from a philosophical and particularly Platonic perspective—is thus closer to representing the assumed reality of an object because it is not restricted to imitating its surface, but it refers to what is beyond the material representation (see Said 1987, 326–27; Steiner 2001, 5).

From a religious perspective, the potential to represent or point to invisible and abstract ‘objects’ makes this term naturally more suitable for the representation of transcendence. Not least due to this (Neo-)Platonic history (for the even more positive use of eikones in Plotin’s Enneads, see Said 1987, 327), the eikôn later becomes the term for Christian images10 in contrast to the negatively connotated eidôlon.

agalma

[…] agalma, an object that through its high quality and craftsmanship inspires delight in its viewer and should prompt the goddesses’ own reciprocal gift of charis (CEG 414). (Steiner 2001, 16)

The term agalma commonly denotes statues and images (of ancient gods) set up in temples. The term agalma underlines the honorable character of these images as a “pleasing gift” (LSJ). Due to its frequent use in Greco-Roman polytheistic Greek texts, for instance in Pausanias, and its sparse use in Jewish and Christian contexts, I have decided to add agalma as a complement to the analysis because “unlike the eidôla critiqued by later philosophers, these representations do not set out to mask their ‘factural’ nature, nor do they seek to dupe their audiences by persuading them of the reality of the pictured scene” (Steiner 2001, 20). The agalmata thus add an interesting layer to the analysis, namely that of impressive man-made artifacts to honor and to remember the gods in the sense of valuable votive offerings void of discussions about their representative qualities. In addition, they will hopefully help to further examine the material dimension of images in both Greco-Roman polytheistic and Jewish as well as Christian texts.

Data and Methodology

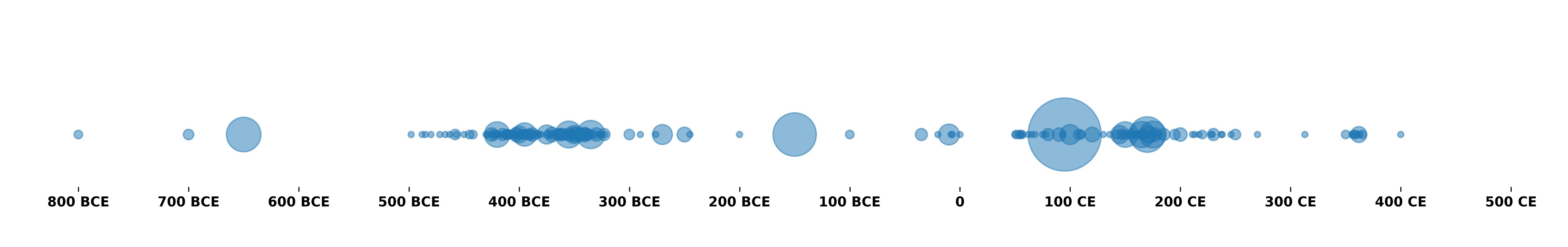

Since large parts of the analysis will be based on quantitative approaches, it is of central importance for this article to rely on a well-structured, digitized, and ideally large data set. Particularly the latter poses a problem when dealing with historical sources that are often scarce and without any realistic potential of being easily expanded. Considering these constraints, the Diorisis corpus, its shortcomings notwithstanding11, builds a promising basis for a quantitative analysis of ancient Greek words because it includes a wide range of texts from several historical periods (see figure 1) in a well-structured and digitized form. In the following parts, I will briefly introduce the Diorisis corpus and further elaborate on the methods and tools applied during the analysis.

Diorisis Ancient Greek Corpus

The Diorisis Ancient Greek Corpus is a digital collection of ancient Greek texts (from Homer to the early fifth century AD) compiled for linguistic analyses, and specifically with the purpose of developing a computational model of semantic change in Ancient Greek. The corpus consists of 820 texts sourced from open access digital libraries. The texts have been automatically enriched with morphological information for each word. (Vatri and McGillivray 2018b)

Besides providing a relatively large and diverse text basis, the rich annotations of the texts in the Diorisis corpus are another crucial factor for the examination of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn. On a word level, these annotations include (among others) lemmas and Part-of-Speech tagging (POS). On a document level, the genre and additional author/date information are provided for each text, which makes it relatively easy to subdivide the corpus during the analysis, for instance, when examining the use and meaning of the three terms in philosophical treatises or religious texts. The annotation of this information in XML format facilitates the processing of the corpus with Python and LancsBox.

For this article’s comparative focus on the use and meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in Greco-Roman polytheistic and Jewish as well as Christian texts, the Diorisis corpus has been subdivided into two subcorpora.

- The first subcorpus includes 91 texts from a primarily Jewish and Christian background. Most of these texts stem from the Greek New Testament and the Septuaginta. Yet, texts from other authors, such as Flavius Josephus, Clement of Alexandria, and Eusebius of Caesarea, are also included. Note that some of the texts have a Jewish background (such as Flavius Josephus and the Septuagint). The relation between early Christianity and Judaism is a complex topic which is beyond the scope of this article (Fialová, Hoblík, and Kitzler 2022; Schäfer and Peterson 2015; Boyarin 2004), not least regarding their views towards images. Consequently, the inclusion of Jewish and Christian texts as part of the same corpus is to some extent problematic. Yet, Jewish texts, their reception in early Christianity, and the “Jewish background” of Christianity (as problematic as this topic is) are still relevant for the shaping of the meaning of the terms in question (the Septuaginta in particular), which is why I have decided to include them in the same corpus.

- The second subcorpus consists of the remaining 729 texts of the Diorisis corpus, which are consequently classified as “Greco-Roman polytheistic” (often abbreviated as GRP in the following diagrams and charts).

The distribution of the texts between the two subcorpora has a considerable bias. Instead of manually adding additional (particularly Jewish and early Christian) texts, I have decided to restrict the analysis to texts in the Diorisis corpus to keep the data basis consistent. Adding additional texts, for instance from Greek church fathers, or adding a third subcorpus with Jewish texts only would have meant to preprocess and annotate these texts similarly as the creators of the Diorisis corpus did, which was not possible for me. Thus, adding more (preferably Jewish-Christian) texts to the analysis remains a desideratum.

From the rich annotation of the texts in the Diorisis corpus, the analysis in this article considers the following fields. On a word level, the annotated lemmas and the morphological information are added to the data set. On a document level, the information about the text genre and the creation date of the texts are collected.

The collocation analysis and the word vector analysis are based on the lemmatized version of the texts, which I have manually created from the annotation in the XML file with the help of a Python script. The lemmatized texts have also been stripped from stop words (such as articles).12 Stop words are words that are commonly used in a language but have little meaning on their own. These words are typically filtered out of natural language processing tasks, such as information retrieval and text mining, because they don’t contain useful information and can often hinder the performance of the algorithm.

Methods

The mixed-methods approach in this article applies three quantitative and computer-driven methods:

- Word distributions (lemmas and types).

- Collocation analysis (lemmas only).

- Word vectors (lemmas only).

The distribution analysis of the types and the creation of word vectors was done in Python using Jupyter notebooks (and gensim for word vectors). The collocation analysis and the analysis of word distributions (lemmas) was conducted with LancsBox (Brezina, Weill-Tessier, and McEnery 2020; Brezina 2018).

A qualitative close reading of selected sentences will complement and evaluate the results of the quantitative analysis. In the following parts, each of these methods will be introduced in more detail.

Word Distribution (Frequency Lists)

The analysis of the word distribution is the most straight-forward quantitative approach applied in this article. It consists of the examination of the absolute and relative frequencies of each term in both subcorpora.

To receive a more detailed insight into the distribution among text genres deemed particularly important for the examination of the meaning and use of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn, the Greco-Roman polytheistic as well as the Jewish and Christian subcorpora are further subdivided into the “full” corpora and two subcorpora including “philosophical” and “religious” texts only (according to the metadata in the Diorisis corpus).

Besides the examination of the distribution of the lemmas, this article also considers the distribution of the morphological variance of each term. Examining the distribution of types helps to discover specific use cases (and thus meanings) of the terms in question. For instance, if one word frequently appears in dative or genitive plural in one subcorpus and in nominative singular in the other corpus, the word could mainly be used for an abstract quantity of objects (that is related to other objects, such as in “the beauty of the statues”) in the first case and as an individual ‘subject’ in the other (“the eikôn of Christ caused an uprising among the monks”).

Collocation Analysis

Collocations are combinations of words that habitually co-occur in texts and corpora. (Brezina 2018, 67)

The collocation analysis attempts to identify which other words (and thus semantic fields) commonly appear in the context of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon. An association measure is applied to evaluate whether certain words only appear in the context of the search terms due to their high frequency in the full text.13 The association measure used in this article is log-likelihood (LL) (see Brezina 2018, 72). The collocation window in this article is L5-R5, meaning that the five words left and right of the search term are considered.

This article adopts the “collocation parameters notation” (CPN) proposed by Brezina in the already cited work (Brezina 2018, 75), which looks like in the following example:

(6-LL, 3, L3-R4, C5-NC5; stop words removed)

This notation represents the parameters used in the collocation analysis and displays the following information: a) statistic ID, b) statistic name, c) statistic cut-off value, d) L and R span, e) minimum collocate frequency (C), f) minimum collocation frequency (NC), and g) optional filters, such as “no stop words.”

The CPN above reads as follows: The association measure log-likelihood was applied (with the ID 6). The statistic cut-off value was 3.14 The collocation analysis considered three words left of the search term and four words right of the search term. The collocate needed to appear at least five times in the whole document and five times in the defined collocation window (L3-R4) of the search term to be considered in the analysis. Stop words such as articles were ignored (or not even part of the text, as in the case of this article, where the processed lemmatized texts have already been stripped from stop words).

Word Vectors (Word2Vec)

Word vectors are representations of words in a text (or corpus) as word vectors of real numbers, created by analyzing the word embeddings of each word. These vectors can be used to compare words with the help of basic algebraic operations. As a result, word vectors that are close to each other (or point into the same direction in the multi-dimensional vector space) represent words with a similar meaning since they have a similar vector representation of their word embeddings. There are different ways to generate word vectors based on word embeddings, among which one of the most popular methods is Word2Vec.15

Besides using Word2Vec to find similar word vectors indicating related semantics in a multi-dimensional vector space, Word2Vec also enables the application of basic semantic calculations. A popular example is that an appropriately trained Word2Vec model is able to deliver the vector of “queen” as a result when subtracting the vector “man” from the vector “king” and adding the vector of “woman.” Even though such semantic equations are tempting for the research question of this article, the word vector analysis only applies Word2Vec (Skip-Gram) to get an impression of the closest words to the terms agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in the Diorisis corpus by using the Word2Vec (Skip-Gram) implementation in gensim.16 Overall, the results of the Word2Vec analysis must be treated with caution due to the relatively small size of the text corpus. Still, it delivered interesting insights into the data, which is why I kept it as part of the examination.

Analysis

The following parts will discuss the results of the quantitative methods introduced above. Each part is complemented with a qualitative close reading of single sentences that relate to the results of the quantitative examination. The analysis will start with an overview of the distribution of the words agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in the various subcorpora.

Word Distribution—Overview

The tables and figures in this section display the distribution of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in the following subcorpora:

- The full Greco-Roman polytheistic text corpus (word count: 8,634,297; text count: 729).

- The Greco-Roman polytheistic text corpus with philosophical texts only (word count: 1,292,595; text count: 56).

- The Greco-Roman polytheistic text corpus with religious texts only (word count: 17,022; text count: 41).

- The Jewish and Christian text corpus (word count: 1,418,531; text count: 91).17

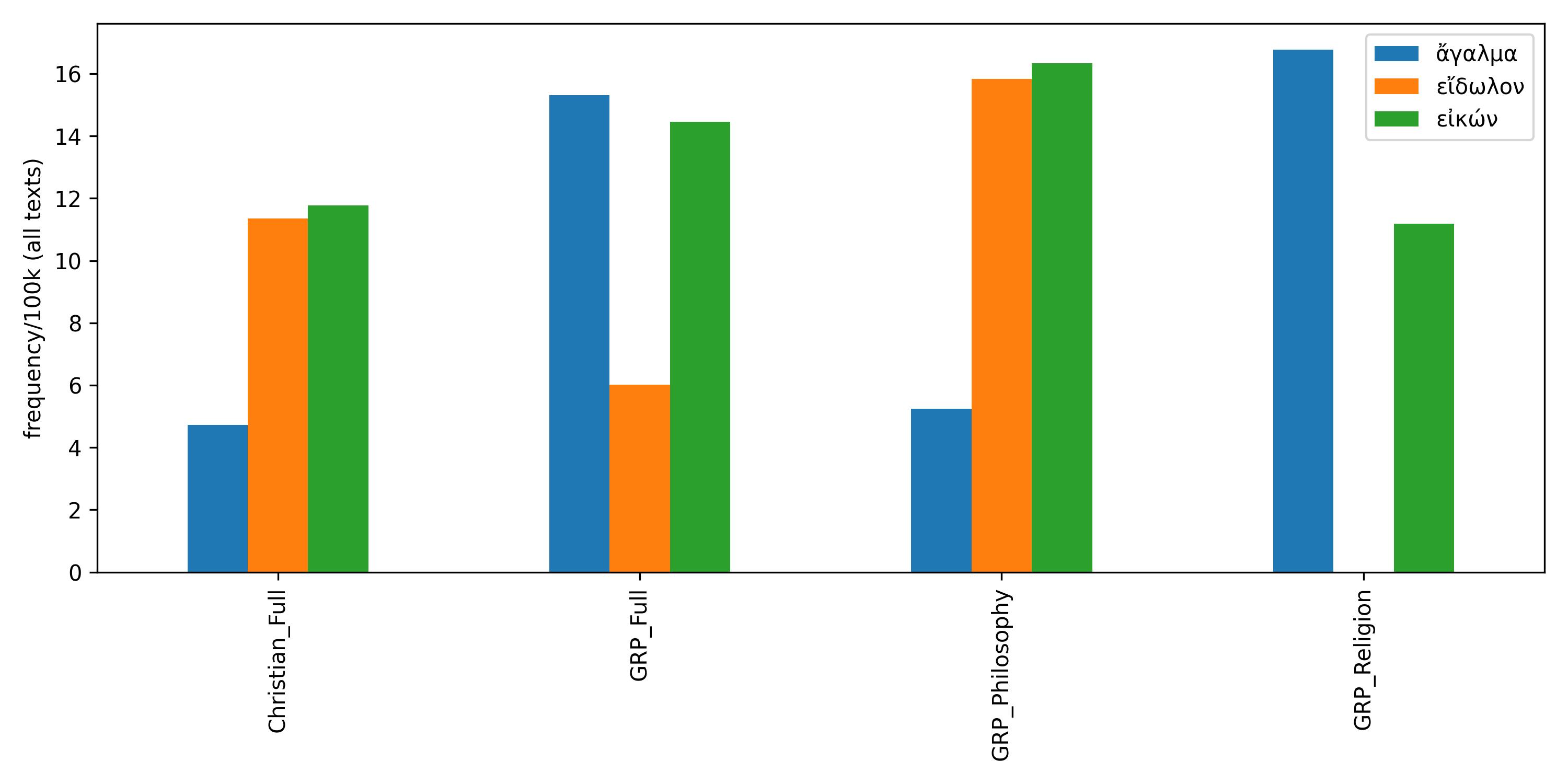

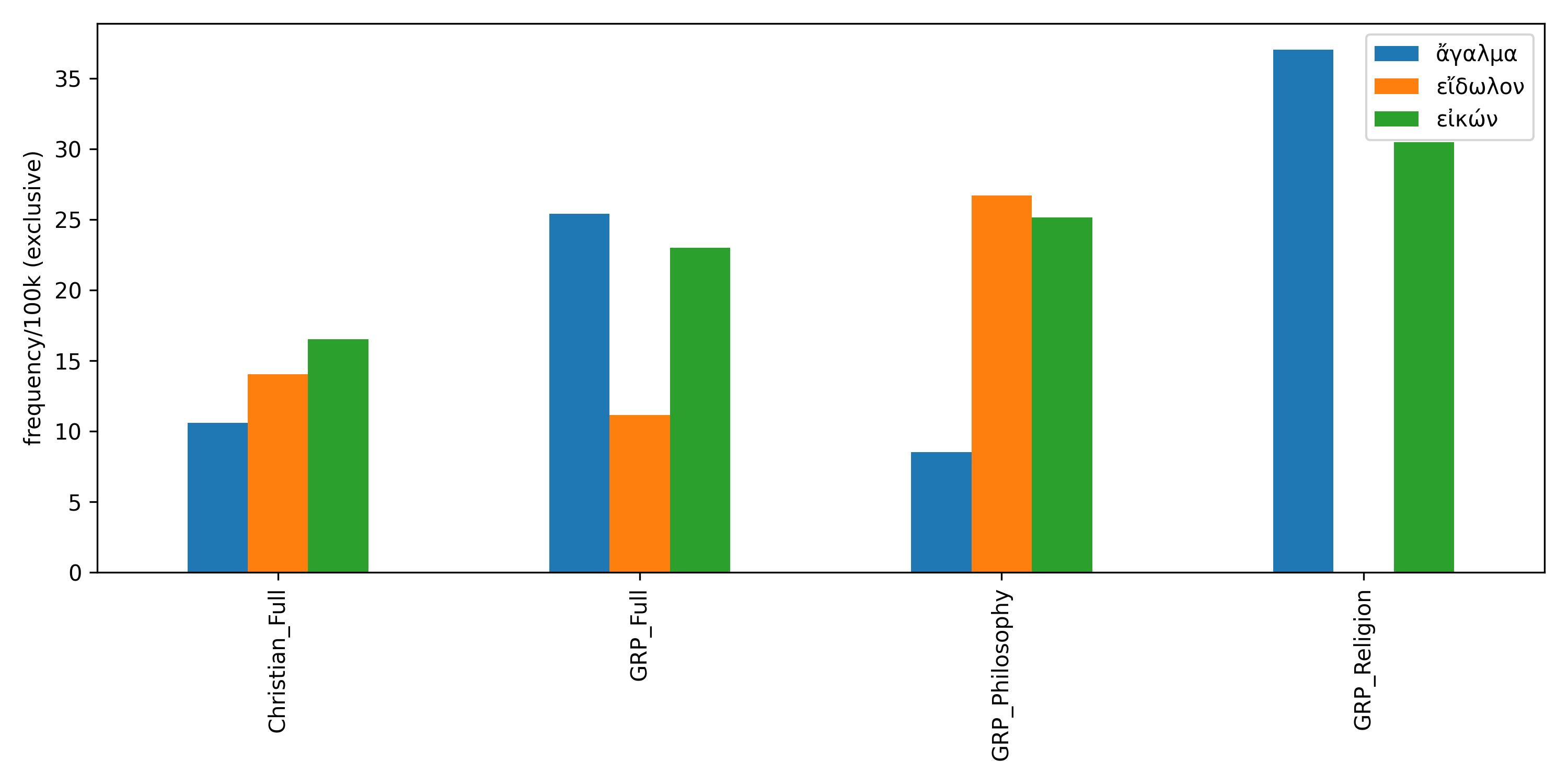

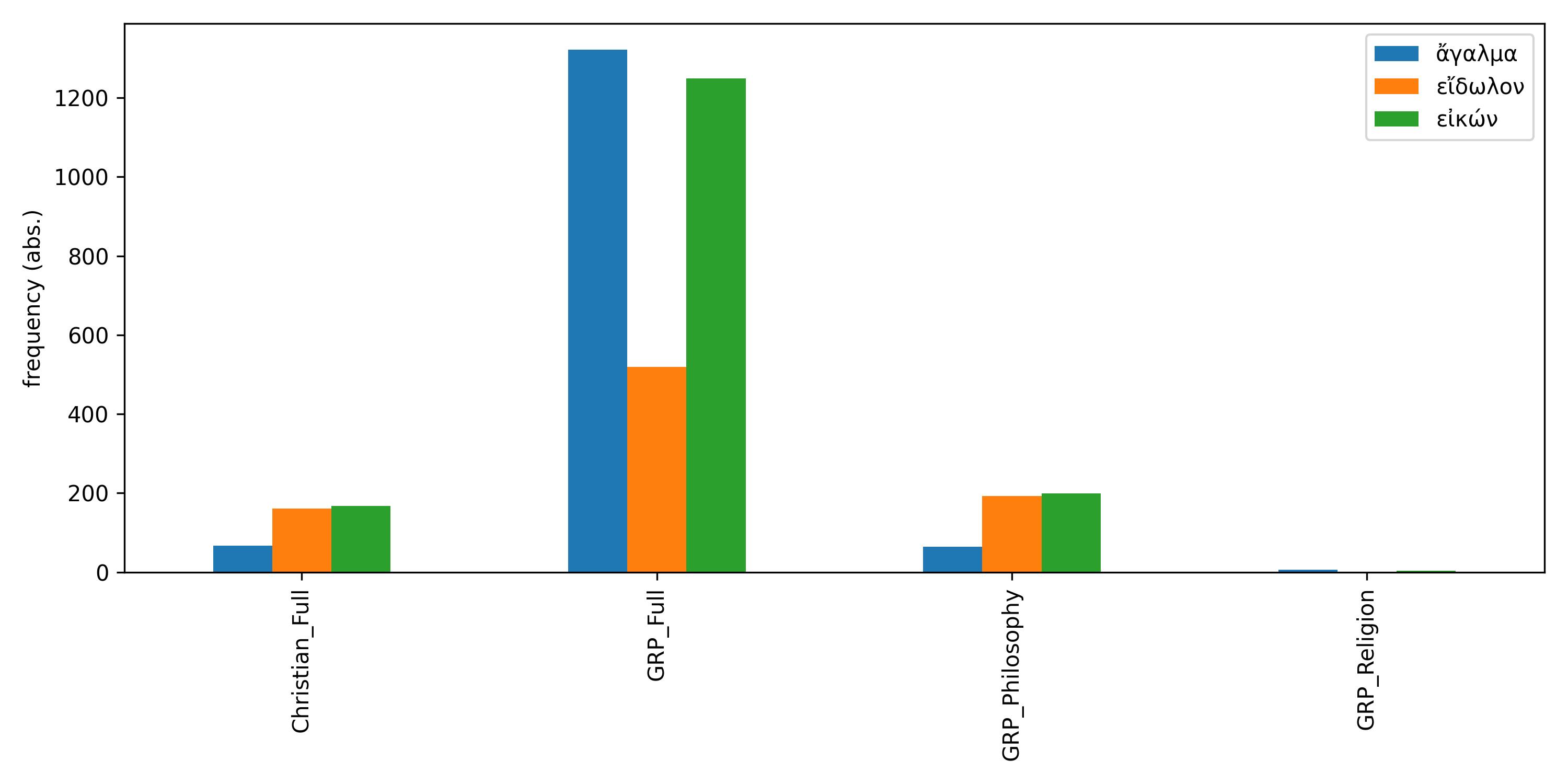

The visualizations in figures 1, 4, and 7 display:

- The relative frequency of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in each subcorpus per 100,000 words, including all texts in the subcorpus (figure 1).

- The relative frequency of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in each subcorpus per 100,000 words, including only texts in the subcorpus in which the term appeared (figure 4).

- The absolute frequency of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in each subcorpus (figure 7).

This threefold analysis helps to evaluate the relative and absolute frequencies of each term in the full text (sub)corpora, while also visualizing the importance of each term in the texts they appear in. For instance, a high number of one of the terms in the latter distribution could prove that the term plays a central role in those texts it is mentioned in. The last distribution including the absolute values provides an overview of the raw distribution of each term in all four subcorpora.

In addition to the visualizations in the figures, the corresponding numbers are also shown in distribution tables in the following parts, where I will discuss the distribution of each term in more detail.

Word Distribution agalma

| full_GRP | philosophy_GRP | religious_GRP | jewish_christian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| word_count_exclusive | 5,202,792 | 751,026 | 16,202 | 632,269 |

| word_count_full | 8,634,297 | 1,218,487 | 35,770 | 1,418,531 |

| texts_including_ἄγαλμα | 161 | 18 | 5 | 7 |

| ἄγαλμα_word_count | 1,322 | 64 | 6 | 67 |

| frequency/100k_exclusive | 25.41 | 8.52 | 37.03 | 10.56 |

| frequency/100k_full | 15.31 | 5.25 | 16.77 | 4.72 |

| text_counter | 729 | 56 | 41 | 91 |

The distribution of agalma in both the visualizations and the table shows that this term is much more important in Greco-Roman polytheistic than in Jewish and Christian texts, although it appears relatively seldom in the Greco-Roman polytheistic texts as well (~15/100k words). Agalma is also more present in Greco-Roman polytheistic religious texts than in Greco-Roman polytheistic philosophical texts, which underlines the assumption in section 2 that eikôn and eidôlon have a rich history in philosophical thought, whereas agalma is mostly used as a descriptive term for votive statues. Yet, the rather high distribution of agalma in Greco-Roman polytheistic religious texts should be treated with caution, since the text basis and thus word counts of these religious texts are rather low.

The distribution of agalma in the subcorpora is also reflected in the following overview of the top texts in each subcorpus in which the term most frequently appears (based on relative frequency per 10k words):

- Full (GRP)

-

Pausanias – Description of Greece (‘word_count’: 215,792; ‘ἄγαλμα’: 694; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 32.16).

- Philosophy (GRP)

-

Plato – Critias (‘word_count’: 4,942; ‘ἄγαλμα’: 3; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 6.07).

- Religious (GRP)

-

Homeric Hymn to Dionysus (‘word_count’: 139; ‘ἄγαλμα’: 1; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 71.94).

- Jewish and Christian

-

Clement of Alexandria – Protrepticus (‘word_count’: 23,015; ‘ἄγαλμα’: 54; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 23.46).

The high relative frequency of agalma in the Homeric Hymn to Dionysos is due to the short character of the text, in which the term only appears once. However, the concrete use of agalma in this short hymn underlines what was stated in section 2 about the votive nature of agalma and its strong focus on materiality, which is why I have kept it despite the term appearing only once:

… καί οἱ ἀναστήσουσιν ἀγάλματα πόλλ᾽ ἐνὶ νηοῖς

… and men will lay up […] many offerings in […] shrines. (Homeric Hymn to Dionysos; transl. by Evelyn-White)

Regarding the Jewish Christian subcorpus, the high frequency of agalma in the Protrepticus is noteworthy (54), particularly considering the rather low frequency of agalma in the rest of the Jewish and Christian corpus (67). This demonstrates that the text by Clement of Alexandria includes a major part of the occurrences of agalma (~81%). Consequently, agalma is only rarely used in the remaining 90 texts in the Jewish and Christian corpus.

That agalmata are extensively mentioned in Pausanias Description of Greece also fits into the overall picture of agalmata as precious votive offerings in temples, because large parts of Pausanias’ work are dedicated to the description of temples, shrines, sanctuaries, and their interiors. The use of agalma in these contexts is almost exclusively applied in the description of the history and material appearance of statues, for example in the following passage:

θέας δὲ ἄξιον τῶν ἐν Πειραιεῖ μάλιστα Ἀθηνᾶς ἐστι καὶ Διὸς τέμενος: χαλκοῦ μὲν ἀμφότερα τὰ ἀγάλματα, ἔχει δὲ ὁ μὲν σκῆπτρον καὶ Νίκην, ἡ δὲ Ἀθηνᾶ δόρυ.

The most noteworthy sight in the Peiraeus is a precinct of Athena and Zeus. Both their images [agalmata] are of bronze; Zeus holds a staff and a Victory, Athena a spear. (Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.1.3; transl. Jones et al.)

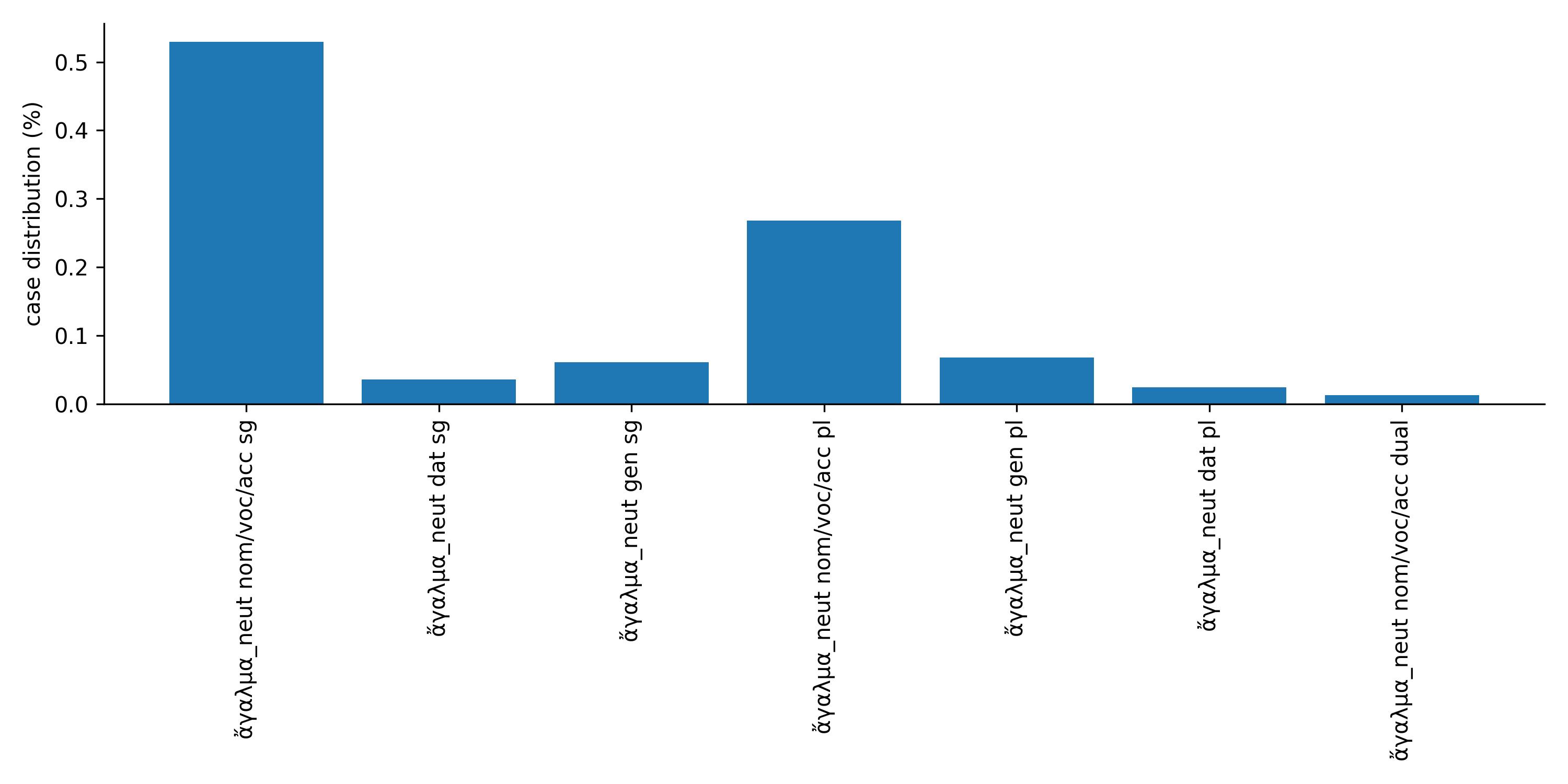

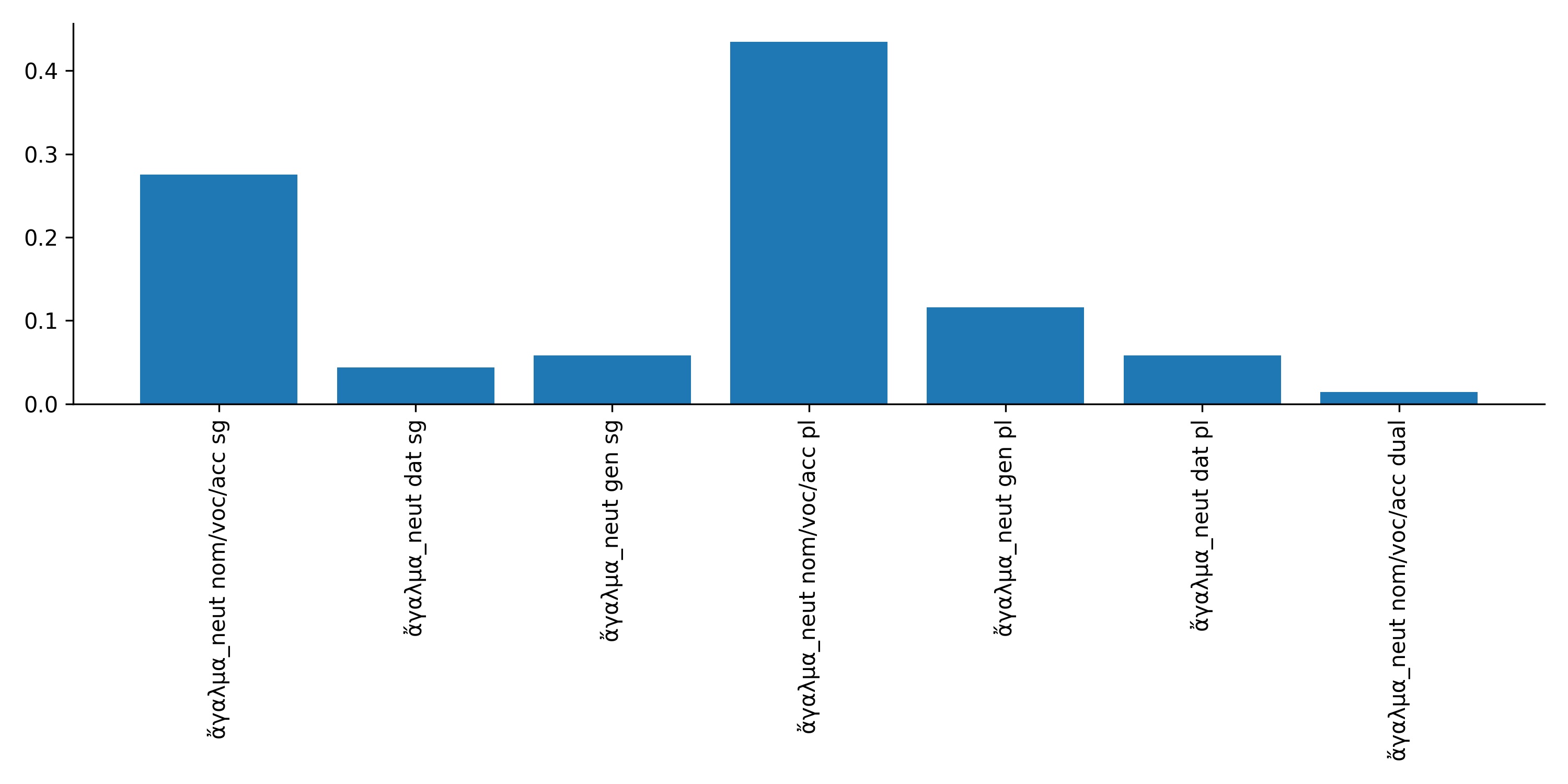

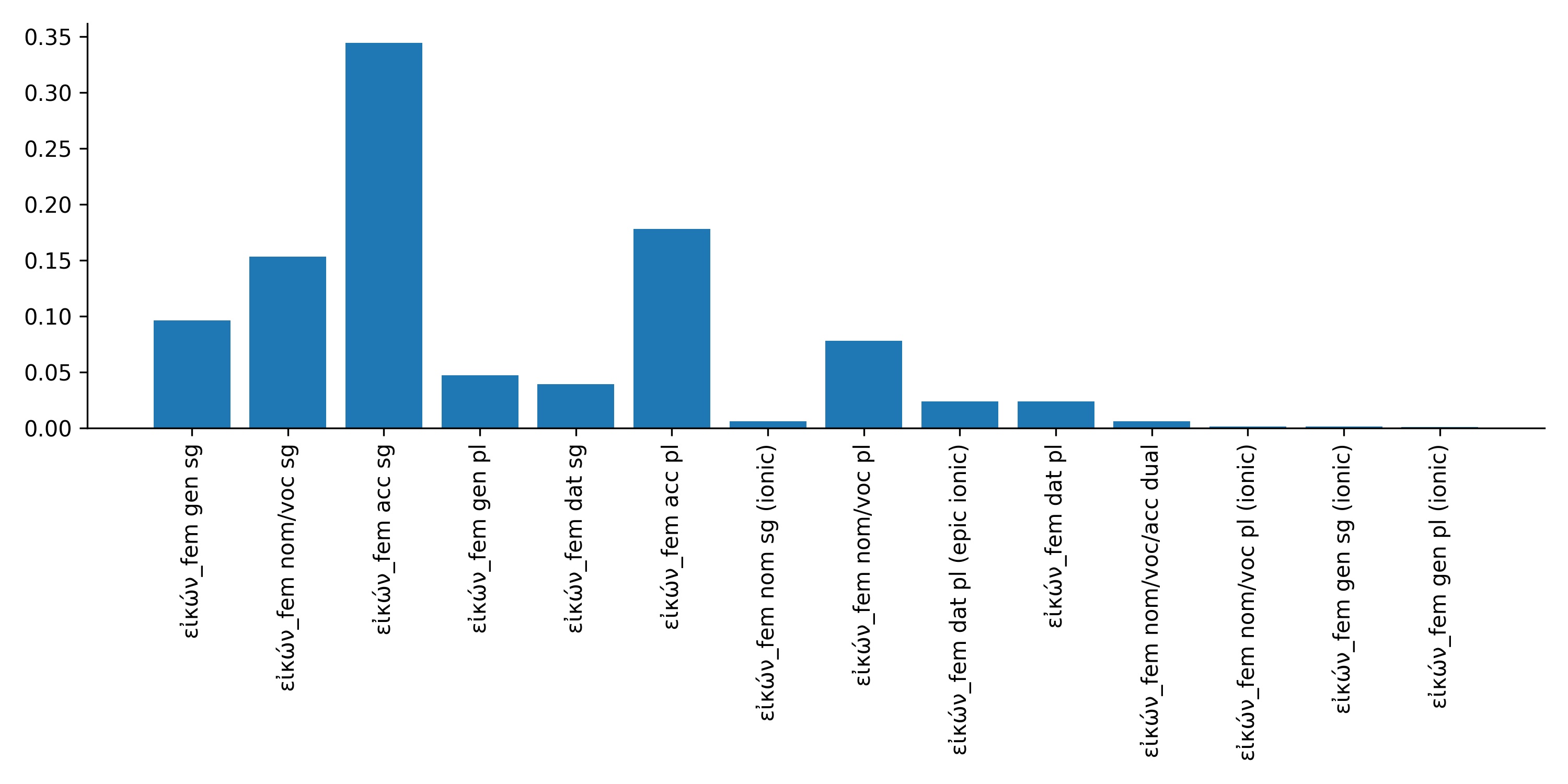

Type Distribution of agalma

The type distribution of agalma in the pagan full corpus is shown in figure 2, whereas the distribution in the Jewish and Christian corpus is displayed in figure 3.

In both the Greco-Roman polytheistic and the Jewish and Christian subcorpora, the term agalma is mostly used in the nominative/accusative cases; however, in the Jewish and Christian corpus, the term frequently occurs in the plural form, thereby referring to multiple images, whereas the focus in the Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus lies on individual agalmata in the singular form. This can be explained considering the previous examinations and shows that an agalma in the Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus often denotes precious individual statues (made by well-known artists such as Praxiteles), whereas the use of agalma in the Jewish and Christian subcorpus refers to a more abstract quantity of agalmata (pl.) in the (often polemical) sense of “all pagan images.”

Word Distribution eidôlon

| full_GRP | philosophy_GRP | religious_GRP | jewish_christian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| word_count_exclusive | 4,661,689 | 722,931 | 0 | 1,148,192 |

| word_count_full | 8,634,297 | 1,218,487 | 0 | 1,418,531 |

| texts_including_εἴδωλον | 128 | 18 | 0 | 42 |

| εἴδωλον_word_count | 519 | 193 | 0 | 161 |

| frequency/100k_exclusive | 11.13 | 26.70 | 0 | 14.02 |

| frequency/100k_full | 6.01 | 15.84 | 0 | 11.35 |

| text_counter | 729 | 56 | 0 | 91 |

The distribution of the term eidôlon shows significant differences compared to the examination of the distribution of agalma. First of all, eidôlon does not appear in the Greco-Roman polytheistic religious corpus (which must be interpreted with caution, since there were only few texts annotated as “religious” in the Diorisis corpus). Yet, the term has a relatively high presence in few philosophical texts (with an exclusive frequency of ~27 words per 100k) and is also mentioned in almost 50% of the Jewish and Christian texts. Thus, eidôlon can be considered to play an important role in some philosophical discussions and to have a relatively widespread use in Jewish and Christian texts.

A closer look at the top texts in each subcorpus supports this assumption:

- Full (GRP)

-

Aristotle – De divinatione per somnum (‘word_count’: 1,199; ‘εἴδωλον’: 5; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 41.70).

- Philosophy (GRP)

-

Plato – Sophist (‘word_count’: 16,018; ‘εἴδωλον’: 13; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 8.12).

- Religious (GRP)

-

-

- Jewish and Christian

-

Septuaginta – Bel et Draco (‘word_count’: 840; ‘εἴδωλον’: 1; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 11.91).

The top texts in the full Greco-Roman polytheistic and the philosophical Greco-Roman polytheistic text corpus are philosophical treatises. Of particular interest is the text by Aristotle, since it deals with a religious topic (divination or “prophetic dreams”) from a philosophical perspective. The following quotes from this text demonstrate that eidôla, in this text, are regarded as ephemeral reflections of an object that cause dreams:

[…] τοιόνδ΄ ἂν εἴη μᾶλλον ἢ ὥσπερ λέγει Δημόκριτος εἴδωλα καὶ ἀποῤῥοίας αἰτιώμενος.

[…] the following would be a better explanation of it than that proposed by Democritus, who alleges ‘images’ [eidôla] and ‘emanations’ as its cause. (transl. by J. I. Beare)

λέγω δὲ τὰς ὁμοιότητας͵ ὅτι παραπλήσια συμβαίνει τὰ φαντάσματα τοῖς ἐν τοῖς ὕδασιν εἰδώλοις͵[…]

But, speaking of ‘resemblances’ [homoiotêtas], I mean that dream presentations [phantasmata] are analogous to the forms [eidôlois] reflected in water, […]

The use of eidôlon in Plato’s Sophist is of a similar kind and mainly designates a (negatively) connotated illusion or phantasma (eidôlon is often used synonymously with phantasma in the Sophist). Plato’s Sophist also includes the important differentiation between “representative art” (technê eikastikê) and “imitating art” (technê mimêtikê), which are both important for Plato’s understanding of images. The first (technê eikastikê) is positively attributed and concerned with the representation of the archetypes (paradeigmata) and attributed to the eikôn, whereas the latter (technê mimêtikê) is an imitation of a representation and thus a work of eidôla.

The top text in the Jewish and Christian subcorpus, which stems from the Septuaginta, is another example of a short text in which the term eidôlon only appears once, thereby causing its high relative frequency.

καὶ ἦν εἴδωλον τοῖς Βαβυλωνίοις, ᾧ ὄνομα Βηλ, καὶ ἐδαπανῶντο εἰς αὐτὸν ἑκάστης ἡμέρας σεμιδάλεως ἀρτάβαι δώδεκα καὶ πρόβατα τεσσαράκοντα καὶ οἴνου μετρηταὶ ἕξ. καὶ ὁ βασιλεὺς ἐσέβετο αὐτὸν καὶ ἐπορεύετο καθ᾽ ἑκάστην ἡμέραν προσκυνεῖν αὐτῷ· Δανιηλ δὲ προσεκύνει τῷ θεῷ αὐτοῦ.

Now the Babylons had an idol [eidôlon], called Bel, and there were spent upon him every day twelve great measures of fine flour, and forty sheep, and six vessels of wine. And the king worshipped it and went daily to adore it: but Daniel worshipped his own God. (transl. King James Bible)

The text with the highest absolute number of appearances of eidôlon is once more the Protrepticus by Clement of Alexandria (24) followed by Eusebius’ Church History (20).

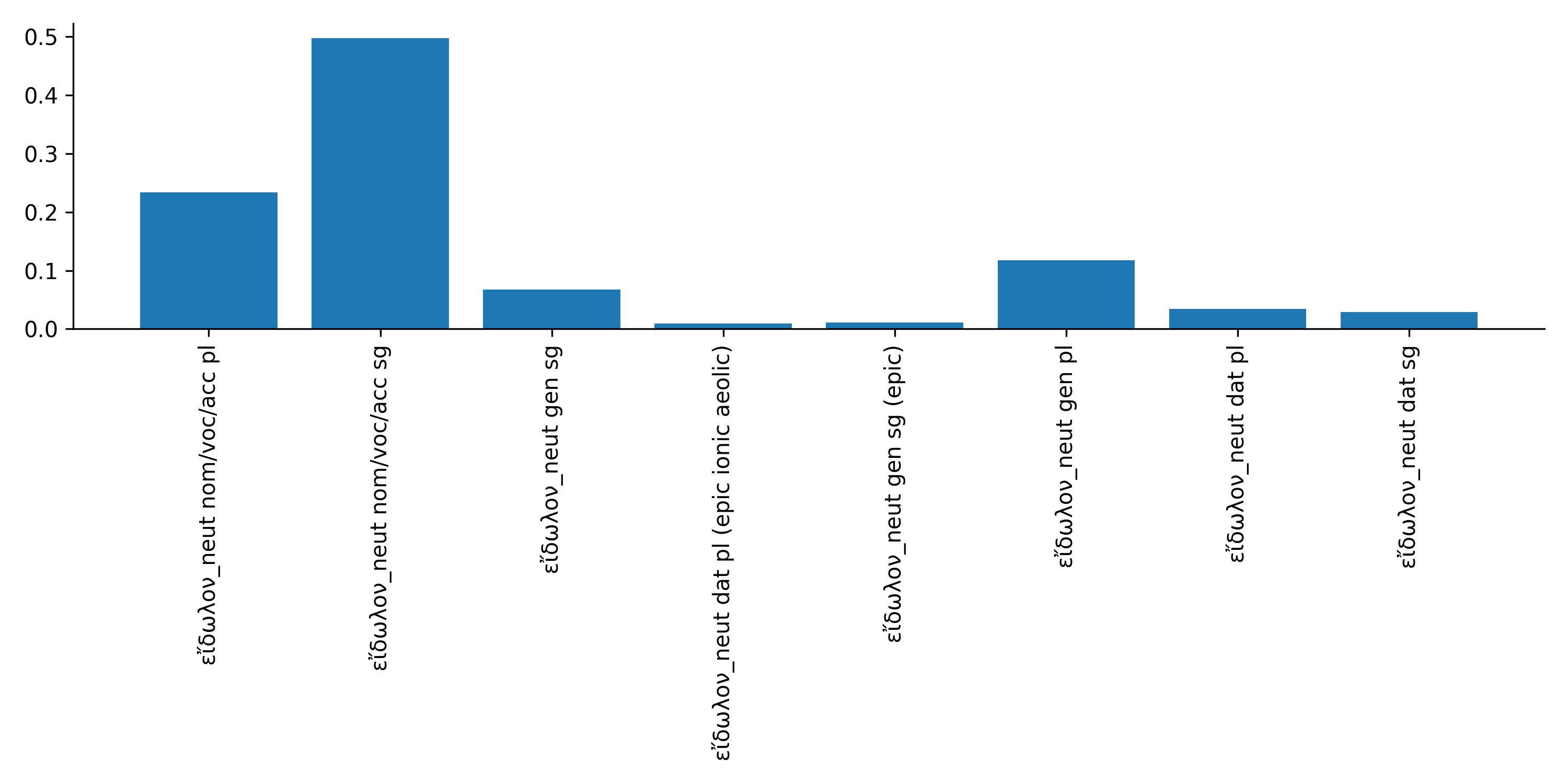

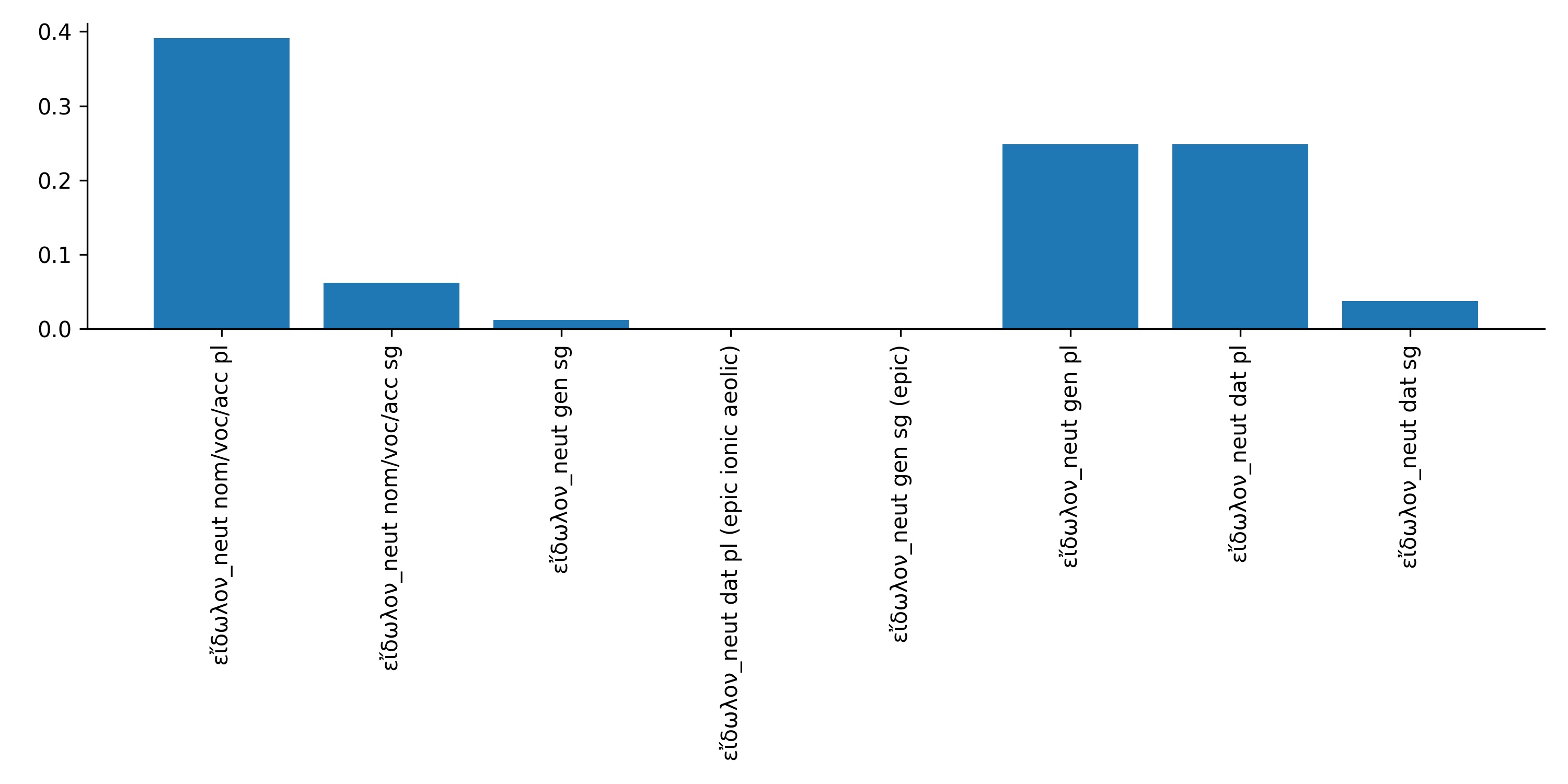

Type distribution eidôlon

The type distribution of eidôlon in the Greco-Roman polytheistic (full) corpus is shown in figure 5, whereas the distribution in the Jewish and Christian corpus is displayed in figure 6.

Similarly to the distribution of agalma, the eidôlon frequently occurs in the nominative/accusative singular in the Greco-Roman polytheistic full corpus. Yet, it also appears in nominative/accusative/genitive plural, although to a lower extent. There is a remarkable difference between the use of eidôlon in the Greco-Roman polytheistic and in the Jewish and Christian corpus. In the latter, the term eidôlon is mostly used in the plural form, including the dative and genitive cases, whereas its singular form is only seldom found.

This observation demonstrates that the eidôla in the Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus, similarly to the agalmata, are regarded as individual phenomena. On the contrary, the use and meaning in the Jewish and Christian corpus conveys a more abstract quality of eidôla by referring to abstract quantities, which can be interpreted as a more general discussion of images as illusions.

Word Distribution eikôn

| full_GRP | philosophy_GRP | religious_GRP | jewish_christian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| word_count_exclusive | 5,433,035 | 791,278 | 13,118 | 1,012,038 |

| word_count_full | 8,634,297 | 1,218,487 | 35,770 | 1,418,531 |

| texts_including_εἰκών | 216 | 21 | 2 | 29 |

| εἰκών_word_count | 1,249 | 199 | 4 | 167 |

| frequency/100k_exclusive | 22.99 | 25.15 | 30.49 | 16.50 |

| frequency/100k_full | 14.47 | 16.33 | 11.18 | 11.77 |

| text_counter | 729 | 56 | 41 | 91 |

The frequencies of eikôn have a similar distribution as those of eidôlon. Yet, the eikôn appears more often in the Jewish and Christian corpus than eidôlon, although in fewer texts (31%). In contrast to the use of eidôlon, the eikôn also occurs in religious Greco-Roman polytheistic texts. It appears to a similar extent as eidôlon in Greco-Roman polytheistic philosophical texts.

The top two texts in each category are:

- Full (GRP)

-

Lucian – Imagines (‘word_count’: 3,183; ‘εἰκών’: 19; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 59.69).

- Philosophy (GRP)

-

Plato – Cratylus (‘word_count’: 17,880; ‘εἰκών’: 21; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 11.75).

- Religious (GRP)

-

Julian the Emperor – Hymn to the Mother of the Gods (‘word_count’: 5,690, ‘εἰκών’: 3, ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 5.27).

- Jewish and Christian

-

Septuaginta – Daniel (‘word_count’: 10,507; ‘εἰκών’: 15; ‘rel_frequency/10k’: 14.28).

Of particular interest in this list is the reappearance of a Platonic dialog in the category of Greco-Roman polytheistic philosophical texts. Furthermore, the text by Julian the Emperor (“Hymn to the Mother of Gods”) is a notable observation since it views a religious cult (that of Cybele and Attis) from a Neo-Platonic perspective and deals with statues and their behavior in various ways. Julian applies several terms to describe the statue of Cybele, among them ksoanon and agalma. Different from material objects, the statue of the Phrygian mother in Julian’s hymn is not lifeless, but her independent behavior demonstrates …

ὡς οὔτε μικροῦ τινος τίμιον ἀπὸ τῆς Φρυγίας ἐπήγοντο φόρτον, ἀλλὰ τοῦ παντὸς ἄξιον, οὔτε ὡς ἀνθρώπινον τοῦτον, ἀλλὰ ὄντως θεῖον, οὔτε ἄψυχον γῆν, ἀλλὰ ἔμπνουν τι χρῆμα καὶ δαιμόνιον.

[…] that the freight they [the Romans] were bringing from Phrygia had no small value, but was priceless, and that this was no work of men’s hands but truly divine, not lifeless clay but a thing possessed of life and divine powers. (transl. by Emily Wilmer Cave Wright)

In the passages where Julian discusses statues as concrete objects, terms such as ksoanon or agalma are applied, whereas the term eikôn is used in a more abstract sense as a philosophical likeness or even a “symbol”18:

κάθαρσις δὲ ὀρθὴ στραφῆναι πρὸς ἑαυτὸν καὶ κατανοῆσαι, πῶς μὲν ἡ ψυχὴ καὶ ὁ ἔνυλος νοῦς ὥσπερ ἐκμαγεῖόν τι τῶν ἐνύλων εἰδῶν καὶ εἰκών ἐστιν.

And the right kind of purification is to turn our gaze inwards and to observe how the soul and embodied Mind are a sort of mould and likeness [eikôn] of the forms that are embodied in matter.

καὶ μὴν καὶ τῶν δένδρων μῆλα μὲν ὡς ἱερὰ καὶ χρυσᾶ καὶ ἀρρήτων ἄθλων καὶ τελεστικῶν εἰκόνας καταφθείρειν οὐκ ἐπέτρεψε καὶ καταναλίσκειν

Moreover in the case of trees it does not allow us to destroy and consume apples, for these are sacred and golden and are the symbols [eikonas] of secret and mystical rewards.

In Plato’s Cratylus, the term eikôn frequently appears in the last third of this treatise that is concerned with the correct naming of objects. Alongside other words for images, such as zôgraphêma, the term eikôn in its relation to the depicted object is applied as an analogy of the word-object relation:

ἆρ᾽ ἂν δύο πράγματα εἴη τοιάδε, οἷον Κρατύλος καὶ Κρατύλου εἰκών, […]

If these only were two distinct objects, just like Cratylus and Cratylus’ image [eikôn], […]

(Pseudo-)Lucian’s dialog eikones about the physical and mental beauty of a certain Panthea from Smyrna is another interesting example of the diverse and complex meaning of eikôn in the texts in the Diorisis corpus. In Lucian’s dialog, the term eikôn is frequently used as a term for statues whose appearance is compared to that of Panthea, thereby once more revealing the ‘referring nature’ of the eikôn.

Turning to the Jewish and Christian corpus, the use of eikôn in Daniel 2:31-34 denotes a concrete statue. It oscillates between underlining its resemblance to physical attributes and its function as a representation that points to something beyond the material object. It also reflects a more pejorative view on images than in most of the other texts discussed so far:

καὶ σύ, βασιλεῦ, ἑώρακας, καὶ ἰδοὺ εἰκὼν μία, καὶ ἦν ἡ εἰκὼν ἐκείνη μεγάλη σφόδρα, καὶ ἡ πρόσοψις αὐτῆς ὑπερφερὴς ἑστήκει ἐναντίον σου, καὶ ἡ πρόσοψις τῆς εἰκόνος φοβερά· καὶ ἦν ἡ κεφαλὴ αὐτῆς ἀπὸ χρυσίου χρηστοῦ, τὸ στῆθος καὶ οἱ βραχίονες ἀργυροῖ, ἡ κοιλία καὶ οἱ μηροὶ χαλκοῖ, τὰ δὲ σκέλη σιδηρᾶ, οἱ πόδες μέρος μέν τι σιδήρου, μέρος δέ τι ὀστράκινον. ἑώρακας ἕως ὅτου ἐτμήθη λίθος ἐξ ὄρους ἄνευ χειρῶν καὶ ἐπάταξε τὴν εἰκόνα ἐπὶ τοὺς πόδας τοὺς σιδηροῦς καὶ ὀστρακίνους καὶ κατήλεσεν αὐτά.

- You saw, O king, and behold, a great image [eikôn]. This image [eikôn], mighty and of exceeding brightness, stood before you, and its appearance was frightening. (32) The head of this image was of fine gold, its chest and arms of silver, its middle and thighs of bronze […] (34) As you looked, a stone was cut out by no human hand, and it struck the image on its feet of iron and clay, and broke them in pieces. (transl. English Standard Version)

This passage from Daniel is of particular interest for the triad of anti-, an-, and iconism mentioned in the introduction of this article. It could be interpreted as an anti-iconic action in which an aniconic object (the mountain) destroys an icon. Even though it might first appear that way, the eikôn in Daniel is more than a mere physical presence or decorative object (such as an agalma), it is the representation and likeness of the king, which is not evoked through any physical resemblance but through genuine functions such as might and awe. This episode about the statue (eikôn) of the king is further elaborated on in Daniel 3, where the Judaeans resist obeying the imperial order to worship the golden image of the king. Overall, this passage demonstrates that the term eikôn, although later more positively connotated in Christian thought, still had a rather negative meaning in various Jewish and Christian contexts depending on the object it represented.

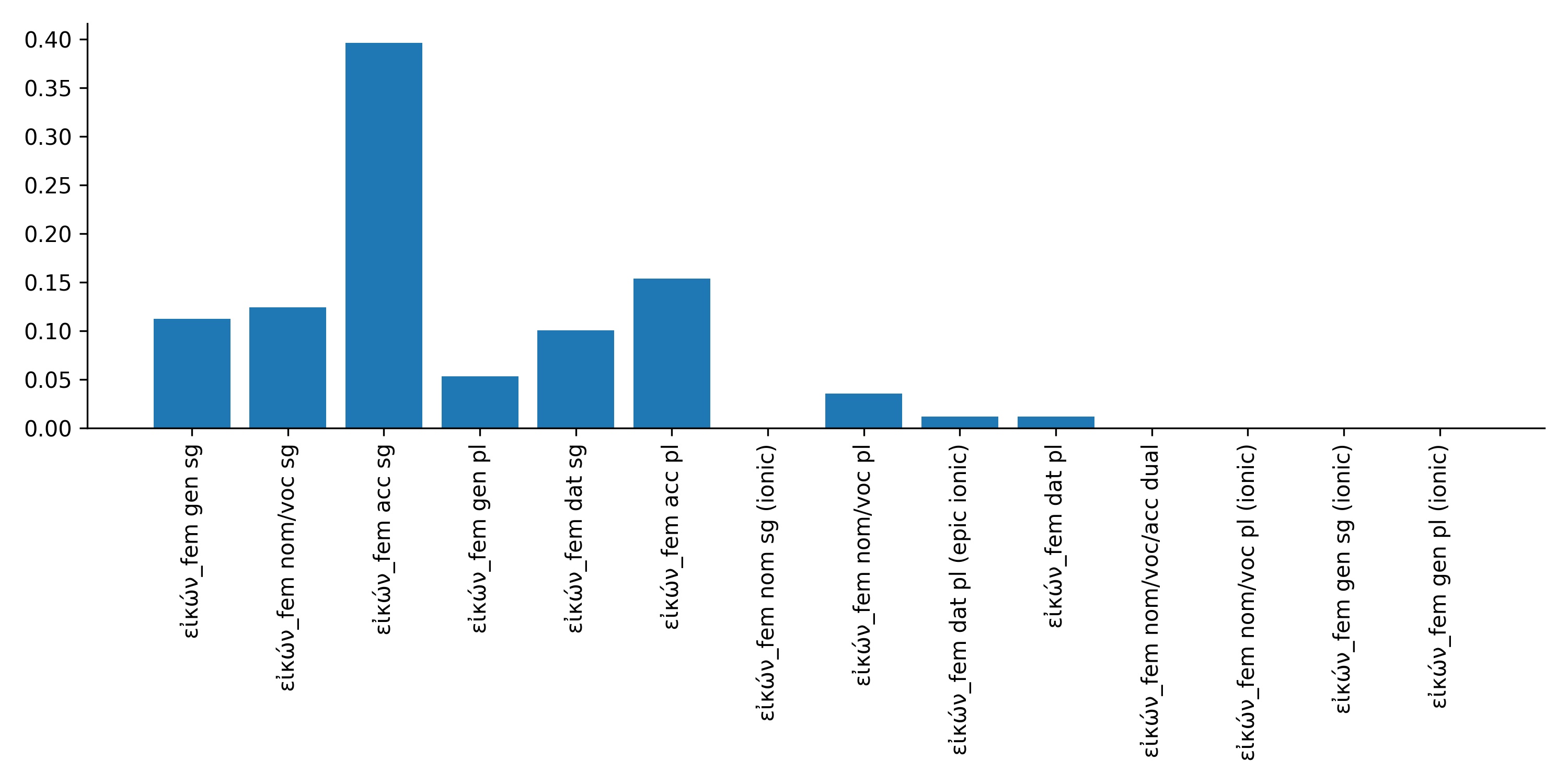

Type distribution eikôn

The type distribution of eikôn in the Greco-Roman polytheistic (full) corpus is shown in figure 8, whereas the distribution in the Jewish and Christian corpus is displayed in figure 9 .

Different from the distributions of types of agalma and eidôlon, the type distribution of eikôn is very similar in the Greco-Roman polytheistic as well as in the Jewish and Christian subcorpora. The term eikôn is mostly used in accusative singular, thereby referring to a single eikôn. This could hint at a continuity in the use and meaning of eikôn in the Greco-Roman polytheistic as well as the Jewish and Christian subcorpora that will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Word Distribution Summary

The distribution of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn revealed important differences between the various subcorpora analyzed in this article. Agalma only appears to a lesser extent in Jewish, Christian, and Greco-Roman polytheistic philosophical texts. Yet, this term is frequently found in the other Greco-Roman polytheistic texts, and to a large extent in those that focus on the description of the materiality of statues and images, such as in the account by Pausanias. Consequently, the examination of the use and meaning of agalma is of central importance for the understanding of the role of materiality in the discussion of images, and its absence in the philosophical as well as most of the Jewish and Christian texts can rightfully be interpreted as a shift from the material to the cognitive dimension in the understanding of images.

Both eidôlon and eikôn are more frequently found in philosophical as well as Jewish and Christian texts than the term agalma. The term eidôlon is very present in Greco-Roman polytheistic philosophical works dealing with dreams or illusions, such as Aristotle’s De divinatione per somnum or Plato’s Sophist. The term eikôn appears to a similar extent in all the subcorpora examined in this article. Its use and meaning covers a wide spectrum, from a more positive (Lucian) to a rather negative perception (Daniel) and from a term that signifies a concrete object (such as the statue of Nebukadnezar in Daniel or Panthea in Lucian’s work) to an abstract understanding in the sense of a “likeness” or “symbol.”

In summary, the analysis of the word frequency lists and selected examples revealed a rather diverse use and meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn both between and within the subcorpora, and particularly in the case of eikôn and eidôlon. For instance, the assumption of a clear distinction between the negatively connotated eidôlon and the eikôn as the term for more accepted images, at least from a Christian perspective, is difficult to maintain since the eikôn could have a negative connotation as well. A good example is the book of Daniel and the chapter of “Bel and the Dragon” where both terms are applied with a negative connotation for divine/royal statues.

Collocation Analysis

Greco-Roman polytheism (Full)

The following collocation analysis will further elaborate on the results from the previous frequency analysis by examining the semantic context in which agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn appear in the documents of the various subcorpora. The first part of the collocation analysis examines the collocation of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in the full Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus.

The top 10 collocates of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in the Diorisis Lemmatized Greco-Roman polytheistic Corpus (No Stop Words) are identified using log-likelihood as an association measure (06 – LogLik (6.63), L5-R5, C: 3.0-NC: 3.0).

agalma

| ID | Position | Collocate | Stat (LogLik) | Freq coll | Freq corpus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L | ναός (temple) | 1900,795 | 203 | 3299 |

| 2 | L | ἀθήνη (Athena) | 1077,964 | 114 | 1710 |

| 3 | R | ποιέω (to make) | 1042,756 | 209 | 30265 |

| 4 | R | λίθος (stone) | 952,191 | 104 | 1798 |

| 5 | L | ἱερόν (sanctuary) | 926,458 | 105 | 2136 |

| 6 | R | ζεύς (Zeus) | 841,753 | 118 | 5569 |

| 7 | L | ἄρτεμις (Artemis) | 741,120 | 74 | 835 |

| 8 | L | θέα (goddess) | 725,237 | 101 | 4625 |

| 9 | L | εἰς (in) | 722,413 | 207 | 65478 |

| 10 | R | ἀπόλλων (Apollon) | 719,981 | 83 | 1801 |

A closer look at the collocates of agalma reveals that most of the associated words refer to:

- Gods and goddesses

- Religious places (temples, sanctuaries)

These findings strongly support the initial assumption that the term agalma is primarily used as a term to designate concrete man-made (indicated by the verb poieô, to make) objects, such as statues, and the context in which they were set up (naos, hieron, temple/sanctuary).

An illustrative example of this common use of agalma as a reference to (a multitude of) statues are the following passages from Herodotus and Pausanias.

δυώδεκά τε θεῶν ἐπωνυμίας ἔλεγον πρώτους Αἰγυπτίους νομίσαι καὶ Ἕλληνας παρὰ σφέων ἀναλαβεῖν, βωμούς τε καὶ ἀγάλματα καὶ νηοὺς θεοῖσι ἀπονεῖμαι σφέας πρώτους καὶ ζῷα ἐν λίθοισι ἐγγλύψαι.

Furthermore, the Egyptians (they said) first used the names of twelve gods (which the Greeks afterwards borrowed from them); and it was they who first assigned to the several gods their altars and images and temples, and first carved figures on stone. (Herodotus 2.4.2; transl. by Godley)

θέας δὲ ἄξιον τῶν ἐν Πειραιεῖ μάλιστα Ἀθηνᾶς ἐστι καὶ Διὸς τέμενος: χαλκοῦ μὲν ἀμφότερα τὰ ἀγάλματα, ἔχει δὲ ὁ μὲν σκῆπτρον καὶ Νίκην, ἡ δὲ Ἀθηνᾶ δόρυ.

The most noteworthy sight in the Peiraeus is a precinct of Athena and Zeus. Both their images are of bronze; Zeus holds a staff and a Victory, Athena a spear. (Pausanias 1.3; transl. by Jones et al.)

eikôn

| ID | Position | Collocate | Stat (LogLik) | Freq coll | Freq corpus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R | χάλκεος (of copper) | 858,225 | 83 | 851 |

| 2 | L | ποιέω (to make) | 548,810 | 132 | 30265 |

| 3 | M | εἰκών (eikôn) | 509,604 | 58 | 1249 |

| 4 | R | ἵστημι (to set up) | 476,273 | 69 | 3800 |

| 5 | L | ὡς (as) | 448,833 | 139 | 52308 |

| 6 | L | ἐπί (on) | 448,527 | 140 | 53429 |

| 7 | R | ἐκεῖνος (that person) | 403,503 | 101 | 24903 |

| 8 | R | εἰς (in) | 372,805 | 135 | 65478 |

| 9 | R | ἀνατίθημι (to dedicate) | 368,993 | 42 | 899 |

| 10 | L | ἔχω (to have) | 360,260 | 116 | 46247 |

The collocates of eikôn in the full Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus include:

- Verbs and prepositions related to the creation or placing of the eikones

- The indication of the materiality of the eikones (chalkeos)

- Interestingly, the term eikôn seems to regularly appear in the context of other eikones.

The term eikôn is often used as a general expression to indicate a likeness, which can but does not necessarily have to be represented in the form of a concrete object (although it is certainly used in this sense, as the close relation with “of copper,” chalkeos, indicates). The application of eikôn to denote a concrete object but with the focus on what is represented is demonstrated in the following example taken from Pausanias, where the eikôn is used together with andrias (another term commonly applied for human statues) to underline the “likeness” of the statue made by Critius:

ἀνδριάντων δὲ ὅσοι μετὰ τὸν ἵππον ἑστήκασιν Ἐπιχαρίνου μὲν ὁπλιτοδρομεῖν ἀσκήσαντος τὴν εἰκόνα ἐποίησε Κριτίας, Οἰνοβίῳ δὲ ἔργον ἐστὶν ἐς Θουκυδίδην τὸν Ὀλόρου χρηστόν:

Of the statues [andriantôn] that stand after the horse, the likeness [eikona] of Epicharinus who practised the race in armour was made by Critius, while Oenobius performed a kind service for Thucydides the son of Olorus. (Pausanias 1.23.9; transl. by Jones et al.)

The use of eikôn in the presence of another eikôn rarely occurs in the sense of an “icon of icons” but mostly due to the dense discussion of (several) eikones. An illustrative example of this application of eikôn can be found in Aristotle’s Rhetoric, where eikones (in the sense of similes) are discussed in the context of metaphors.

ἔστιν δὲ καὶ ἡ εἰκὼν μεταφορά: διαφέρει γὰρ μικρόν: […] καὶ ὡς Ἀντισθένης Κηφισόδοτον τὸν λεπτὸν λιβανωτῷ εἴκασεν, ὅτι ἀπολλύμενος εὐφραίνει. πάσας δὲ ταύτας καὶ ὡς εἰκόνας καὶ ὡς μεταφορὰς ἔξεστι λέγειν, ὥστε ὅσαι ἂν εὐδοκιμῶσιν ὡς μεταφοραὶ λεχθεῖσαι, δῆλον ὅτι αὗται καὶ εἰκόνες ἔσονται, καὶ αἱ εἰκόνες μεταφοραὶ λόγου δεόμεναι.

The simile [eikôn] also is a metaphor [metaphora]; for there is very little difference. […] Antisthenes likened the skinny Cephisodotus to incense, for he also gives pleasure by wasting away. All such expressions may be used as similes [eikonas] or metaphors [metaphoras], so that all that are approved as metaphors will obviously also serve as similes [eikones] which are metaphors without the details. (Aristotle, Rhetoric 3.4.2-4; transl. by Freese)

This passage also illustrates the use of hôs (“like,” “as”) in the context of eikones, which is another word frequently appearing in the context of eikôn according to the collocation analysis. The use of eikôn in Aristotle is a good example of the above-mentioned application of eikones in a philosophical context that adds an interesting layer to the concrete and abstract understanding of an eikôn, namely that of a rhetorical figure.

Overall, the collocation analysis of eikôn in the full Greco-Roman polytheistic subcorpus shows that an eikôn does have a material layer (just like agalma). However, it also expresses the “likeness” of an image, meaning that it refers to what is beyond the image and its material representation. This more abstract layer of eikôn culminates in the application of eikôn in Aristotle’s Rhetoric, where the eikôn is a rhetorical figure, just like a metaphor, denoting a simile.

eidôlon

| ID | Position | Collocate | Stat (LogLik) | Freq coll | Freq corpus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | εἴδωλον (eidolon) | 520,086 | 44 | 519 |

| 2 | L | κάτοπτρον (mirror) | 291,126 | 22 | 131 |

| 3 | L | ψυχή (psyche) | 229,098 | 36 | 6276 |

| 4 | M | σκιά (shadow) | 213,722 | 20 | 399 |

| 5 | L | ἄλλος (other) | 190,954 | 53 | 39077 |

| 6 | R | ἠέ (ah!) | 188,075 | 56 | 47191 |

| 7 | L | ὥσπερ (like) | 181,714 | 36 | 12278 |

| 8 | L | λέγω (to say) | 170,071 | 48 | 36361 |

| 9 | R | ὡς (like) | 157,270 | 52 | 52308 |

| 10 | R | εἰς (in) | 154,420 | 56 | 65478 |

The collocates of eidôlon in the full Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus include:

- Words related to ephemeral phenomena, such as a shadow, psyche, or mirror

- Adverbs such as “like” that are used in comparisons

Similar to the observation in the collocation analysis of eikôn, eidôlon regularly appears in the context of other eidola as well.

The co-occurrence of eidôlon with mirror (katoptron) and psychê is frequently found in (Neo-)Platonic texts, particularly in Plotin’s Enneads.

Ἢ οὐδὲ εἴδωλον κατόπτρου μὴ ὄντος ἤ τινος τοιούτου.

Precisely as in the absence of a mirror, or something of similar power, there would be no reflection [eidôlon]. (Plotin 3.6.14; transl. by MacKenna et al.)

During the discussion of animals and their souls in the first book of the Enneads, Plotin uses the eidôlon of the soul to refer to something that “is there but not there to them [the animals]” (ἀλλὰ παρὸν οὐ πάρεστιν αὐτοῖς):

Τὰ δὲ θηρία πῶς τὸ ζῷον ἔχει; Ἢ εἰ μὲν ψυχαὶ εἶεν ἐν αὐτοῖς ἀνθρώπειοι, ὥσπερ λέγεται, ἁμαρτοῦσαι, οὐ τῶν θηρίων γίνεται τοῦτο, ὅσον χωριστόν, ἀλλὰ παρὸν οὐ πάρεστιν αὐτοῖς, ἀλλ´ ἡ συναίσθησις τὸ τῆς ψυχῆς εἴδωλον μετὰ τοῦ σώματος ἔχει· σῶμα δὴ τοιόνδε οἷον ποιωθὲν ψυχῆς εἰδώλῳ· εἰ δὲ μὴ ἀνθρώπου ψυχὴ εἰσέδυ, ἐλλάμψει ἀπὸ τῆς ὅλης τὸ τοιοῦτον ζῷον γενόμενόν ἐστιν.

And the animals, in what way or degree do they possess the Animate? If there be in them, as the opinion goes, human Souls that have sinned, then the Animating-Principle in its separable phase does not enter directly into the brute; it is there but not there to them; they are aware only of the image of the Soul [to tês psychês eidôlon] [only of the lower Soul] and of that only by being aware of the body organised and determined by that image. If there be no human Soul in them, the Animate is constituted for them by a radiation from the All-Soul. (Plotin 1.1.11)

The use of an eidôlon as a “shadow” is also frequently found in the Greco-Roman polytheistic subcorpus, among others in Plutarch’s works and Sophocles’ Philoctet. Just like the use of eidôlon in Plotin, its use oftentimes evokes rather negative or imperfect associations, such as “death” or the “underworld”:

[…] κοὐκ οἶδ᾽ ἐναίρων νεκρὸν ἢ καπνοῦ σκιάν, εἴδωλον ἄλλως:

[…] and does not see that he is cutting down a corpse, the shadow of smoke, a mere phantom [eidôlon]. (Sophocles, Philoctet, 945-946; transl. by Richard Jebb)

All these passages indicate that the term eidôlon is indeed related to a specific realm of representations, namely that of reflections and ephemeral phenomena such as phantoms. This relation does not necessarily include a negative connotation in the Greco-Roman polytheistic texts, but its delusive character is underlined, particularly when compared to other kinds of representations (such as the eikôn) or real objects (which the eidôlon only superficially represents).

Jewish and Christian Corpus (Full)

Following up on the discussion of the collocation analysis in the Greco-Roman polytheistic full text corpus, I will now continue with the analysis of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn in the Diorisis Lemmatized Jewish and Christian Corpus (No Stop Words).

The top 10 collocates identified using log-likelihood (06 – LogLik (6.63), L5-R5, C: 3.0-NC: 3.0) are displayed in the following tables.

agalma

| ID | Position | Collocate | Stat (LogLik) | Freq coll | Freq corpus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L | ὕλη (matter) | 79,466 | 7 | 126 |

| 2 | M | ἄγαλμα (agalma) | 73,956 | 6 | 67 |

| 3 | R | ἀφροδίτη (Aphrodite) | 73,313 | 5 | 19 |

| 4 | M | λίθος (stone) | 68,680 | 8 | 569 |

| 5 | M | κύπριος (Cyprian) | 63,742 | 4 | 9 |

| 6 | M | ξύλον (wood) | 51,425 | 6 | 423 |

| 7 | R | ἠέ (ah!) | 49,549 | 9 | 3046 |

| 8 | L | θέα (goddess) | 48,178 | 5 | 206 |

| 9 | L | αἰσθητός (perceptible) | 46,450 | 3 | 8 |

| 10 | L | ἀναισθησία (insensibility) | 44,144 | 3 | 11 |

The collocation analysis of the term agalma includes words that are related to:

- Materiality (“matter,” “stone,” “wood,” etc.).

- (Greco-Roman) deities.

- Terms related to the senses.

Most of the top terms in the collocation analysis appear exclusively in Clement of Alexandria’s Protrepticus (in which the term eidôlon occurs 54 times), thereby demonstrating how important this text is for the overall use of agalma in the Jewish and Christian corpus. Consequently, agalma is only seldomly used in the other texts in the Jewish and Christian subcorpus.

The term hyle (matter) in connection with agalma appears mainly in Book 4 of the Protrepticus and can be regarded as representative for the use of the other material terms as well (such as “wood,” ksylon, or “stone,” lithos).

Ὡς μὲν οὖν τοὺς λίθους καὶ τὰ ξύλα καὶ συνελόντι φάναι τὴν ὕλην ἀγάλματα ἀνδρείκελα ἐποιήσαντο, οἷς ἐπιμορφάζετε εὐσέβειαν συκοφαντοῦντες τὴν ἀλήθειαν, ἤδη μὲν αὐτόθεν δῆλον:

It is now, therefore, self-evident that out of stones and blocks of wood, and, in one word, out of matter, men fashioned statues resembling the human form, to which you offer a semblance of piety, calumniating the truth. (Clement of Alexandria, Protrepticus, Book 4; transl. by Butterworth)

ἄλλων ἀνθρώπων οἱ ἔτι παλαιότεροι ξύλα ἱδρύοντο περιφανῆ καὶ κίονας ἵστων ἐκ λίθων: ἃ δὴ καὶ ξόανα προσηγορεύετο διὰ τὸ ἀπεξέσθαι τῆς ὕλης. ἀμέλει ἐν Ἰκάρῳ τῆς Ἀρτέμιδος τὸ ἄγαλμα ξύλον ἦν οὐκ εἰργασμένον, καὶ τῆς Κιθαιρωνίας Ἥρας ἐν Θεσπείᾳ πρέμνον ἐκκεκομμένον:

Other people still more ancient erected conspicuous wooden poles and set up pillars of stones, to which they gave the name xoana, meaning scraped objects, because the rough surface of the material had been scraped off. Certainly the statue [agalma] of Artemis in Icarus was a piece of unwrought timber, and that of Cithaeronian Hera in Thespiae was a felled tree-trunk. (Clement of Alexandria, Protrepticus, Book 4)

These two quotes illustrate the use of the term agalma and its close connection with the material quality of an object that, in the case of the Jewish and Christian corpus, is regarded as problematic. The materiality of the statues which was formerly considered as a neutral or even positive part of the description of images (such as in Pausanias Description of Greece) turns into one of the central points of critique, namely the delusive worship of “insensible” (anasthêsia) material—albeit precious—objects.

eikôn

| ID | Position | Collocate | Stat (LogLik) | Freq coll | Freq corpus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | εἰκών (eikôn) | 196,386 | 18 | 167 |

| 2 | R | θεός (god) | 182,890 | 39 | 8514 |

| 3 | L | ἄνθρωπος (human) | 168,304 | 28 | 3001 |

| 4 | L | κατά (downwards) | 164,403 | 35 | 7508 |

| 5 | L | προσκυνέω (to worship) | 149,580 | 17 | 437 |

| 6 | R | ποιέω (to make) | 144,568 | 30 | 5945 |

| 7 | L | θηρίον (animal) | 106,630 | 12 | 291 |

| 8 | R | ὁμοίωσις (likeness) | 93,542 | 7 | 21 |

| 9 | R | πᾶς (all) | 85,806 | 27 | 12548 |

| 10 | R | ἵστημι (to put) | 83,535 | 13 | 1077 |

The top terms in the collocation analysis of eikôn in the Jewish and Christian subcorpus include:

- Verbs partly related to religion (“to worship,” “to make,” “to put”)

- Nouns and adjectives from diverse domains (“god,” “likeness,” “animal”)

The terms related to eikôn in the collocation analysis stem to a great extent from the Protrepticus, but they are also present in other texts, such as the Septuaginta and the New Testament.

The importance of god (theos) is of special interest in the collocation analysis of eikôn since theos frequently appears in a very close connection with eikôn in the sense of “(after) the image/likeness of God”:

καὶ ἐποίησεν ὁ θεὸς τὸν ἄνθρωπον, κατ᾽ εἰκόνα θεοῦ ἐποίησεν αὐτόν, ἄρσεν καὶ θῆλυ ἐποίησεν αὐτούς.

So God created man in his own image, in the image [eikona] of God he created him; male and female he created them. (Gen 1:27)

This quote from the Book of Genesis also demonstrates the typical use of the verb “to make” in the context of eikôn in the Jewish and Christian corpus. The eikôn is often applied to express that something is made in view of the eikôn, which is not necessarily an insensible object (as the frequent appearance of “human being,” anthrôpos, demonstrates).

Different from the eikôn as a “likeness,” the verb “to worship” (proskyneô) together with eikôn hints at a concrete material object. This worship of an object is negatively connotated and the worshiped eikôn thus distinguished from the above-mentioned eikôn of god, oftentimes by underlining its material character. Examples are the already-mentioned golden eikôn in Daniel or the animalic eikôn in the book of Revelation:

ὅταν ἀκούσητε τῆς φωνῆς τῆς σάλπιγγος, σύριγγος καὶ κιθάρας, σαμβύκης καὶ ψαλτηρίου, συμφωνίας καὶ παντὸς γένους μουσικῶν, πεσόντες προσκυνήσατε τῇ εἰκόνι τῇ χρυσῇ, ἣν ἔστησε Ναβουχοδονοσορ βασιλεύς·

[…] that when you hear the asound of the horn, pipe, lyre, trigon, harp, bagpipe, and every kind of music, you bare to fall down and worship the golden image [tê eikoni tê xrysê] that King Nebuchadnezzar has set up. (Daniel 3:5)

καὶ ἐδόθη αὐτῷ δοῦναι πνεῦμα τῇ εἰκόνι τοῦ θηρίου, ἵνα καὶ λαλήσῃ ἡ εἰκὼν τοῦ θηρίου καὶ ποιήσῃ [ἵνα] ὅσοι ἐὰν μὴ προσκυνήσωσιν τῇ εἰκόνι τοῦ θηρίου ἀποκτανθῶσιν.

And it was allowed to give breath to the image of the beast [tê eikoni tou têriou], so that the image of the beast might even speak and might cause those who would not worship the image of the beast to be slain. (Rev 13:15)

Overall, the eikôn in the context of the Jewish and Christian corpus denotes two aspects: Firstly, it is positively connotated not as an individual statue or image but as a likeness or representation of god that manifests itself in living human beings and not in “dead” images. Secondly, it is further and explicitly characterized as a “heathen” object of worship by underlining its material form (golden, animalic). Similar to the observations in the context of agalma, it is noteworthy that the former positive or neutral use of material attributes (such as golden) in the Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus is inverted in the Jewish and Christian context.

eidôlon

| ID | Position | Collocate | Stat (LogLik) | Freq coll | Freq corpus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R | θεός (god) | 193,051 | 40 | 8514 |

| 2 | L | πᾶς (all) | 150,693 | 38 | 12548 |

| 3 | R | ποιέω (to make) | 139,910 | 29 | 5945 |

| 4 | L | σύ (you) | 138,947 | 42 | 19909 |

| 5 | L | ἐγώ (I) | 113,899 | 38 | 21006 |

| 6 | L | ἐπί (on) | 112,954 | 33 | 14270 |

| 7 | R | ἔθνος (heathen) | 96,146 | 16 | 1716 |

| 8 | R | θύω (to sacrifice) | 73,677 | 9 | 317 |

| 9 | R | δαίμων (demon/deity) | 70,540 | 7 | 97 |

| 10 | R | λατρεύω (to worship) | 55,201 | 6 | 127 |

The last term examined in the collocation analysis is eidôlon. The top words in the Jewish and Christian subcorpus display notable differences compared to the use in the Greco-Roman polytheistic subcorpus. Besides the top word “god,” which was also among the top words in the collocation analysis of eikôn, there are many words related to religion, such as “demon,” “to sacrifice,” and “to worship.”

In contrast to the use of “god” in the context of eikôn, the “god” in the context of eidôla does not denote the Christian god but Greco-Roman deities, which is often underlined by additional attributions, such as “demons,” or by underlining their material aspects.

πῶς οὖν ἔτι θεοὶ τὰ εἴδωλα καὶ οἱ δαίμονες, βδελυρὰ ὄντως καὶ πνεύματα ἀκάθαρτα, πρὸς πάντων ὁμολογούμενα γήινα καὶ δεισαλέα, κάτω βρίθοντα, ‘περὶ τοὺς τάφους καὶ τὰ μνημεῖα καλινδούμενα,’ περὶ ἃ δὴ καὶ ὑποφαίνονται ἀμυδρῶς ‘σκιοειδῆ φαντάσματα’; ταῦθ̓ ὑμῶν οἱ θεοὶ τὰ εἴδωλα, αἱ σκιαὶ […]

How then can the shadows and daemons any longer be gods, when they are in reality unclean and loathsome spirits, admitted by all to be earthy and foul, weighed down to the ground, and “prowling round graves and tombs” where also they dimly appear as “ghostly apparitions”? These are your gods, these shadows [eidôla] and ghosts; […] (Clement of Alexandria, Protrepticus, Book 4)

ἐγὼ κύριος ὁ θεὸς ὑμῶν. οὐκ ἐπακολουθήσετε εἰδώλοις καὶ θεοὺς χωνευτοὺς οὐ ποιήσετε ὑμῖν· ἐγὼ κύριος ὁ θεὸς ὑμῶν.

I am the Lord your God. Do not turn to idols [eidôlois] or make for yourselves any gods of cast metal: I am the Lord your God. (Lev 19:3-4)

The several verbs related to “worship” point into a similar direction, namely the negatively connotated worship of the Greco-Roman deities (note the interesting term eidôleion here):

εἶτα πιστὴν γυναῖκα, Κοΐνταν καλουμένην, ἐπὶ τὸ εἰδωλεῖον ἀγαγόντες, ἠνάγκαζον προσκυνεῖν:

Then they carried to their idol temple [eidôleion] a faithful woman, named Quinta, that they might force her to worship. (Eusebius, Church History, 6.41.4)

The same negative connotation is found in the Old Testament:

καὶ οὕτως ἐποίησεν πάσαις ταῖς γυναιξὶν αὐτοῦ ταῖς ἀλλοτρίαις, ἐθυμίων καὶ ἔθυον τοῖς εἰδώλοις αὐτῶν·

And so he did for all his foreign wives, who made offerings and sacrificed to their gods [eidôlois]. (1 Kings 11:7)

In summary, the use of eidôlon in the Jewish and Christian context demonstrates a clear difference compared to its use in the Greco-Roman polytheistic subcorpus. Whereas it was described as an almost natural, sometimes delusive, phenomenon in the latter, its application in the Jewish and Christian context evokes a clearly negative associative context, namely that of material and thus false pagan deities who are the inverse of the Jewish and Christian god.

Collocation Analysis Summary

The collocation analysis of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon has revealed both continuities and differences in the use of each term between the Greco-Roman polytheistic and the Jewish and Christian subcorpora.

The frequent and widespread application of agalma in the Greco-Roman polytheistic texts disappeared in the Jewish and Christian texts. The term was almost exclusively found in Clement of Alexandria’s Protrepticus. The formerly positive attribution of the precious and artistic character of agalmata turned into the opposite: In the Jewish and Christian context, it was precisely this focus on “dead” materials such as wood or gold that made these statues worthless or even dangerous.

Even though it was not immediately visible from the two collocation tables, the use and meaning of eikôn between the Greco-Roman polytheistic as well as the Jewish and Christian subcorpora was more continuous than in the case of the two other terms. In the Greco-Roman polytheistic texts, the use of eikôn was already twofold: It could denote concrete objects, such as images or statues; however, its reference to that what was represented in these images (“likeness”) or even the abstract use of eikôn void of any concrete objects (such as in the context of metaphors in Aristotle) was perceivable as well. This ambiguous meaning oscillating between the object (signans) and that what it refers to (significatum) was also visible in the Jewish and Christian texts. Here, the eikôn in the sense of a material object was often negatively connotated, whereas the more abstract use of eikôn (“man as a likeness of god”) was positively attributed, for instance via a direct connection to the Christian god.

The application and meaning of eidôlon revealed an interesting shift in meaning between the two subcorpora. The partly negative connotation of an eidôlon in the sense of a superficial/incomplete representation in the Greco-Roman polytheistic texts was taken up in the Jewish and particularly Christian subcorpus and established as the pejorative notion for images no longer signifying a visual phenomena (such as reflections) but the entirety of Greco-Roman polytheistic images.

Word Vectors with Word2Vec

The last part of the analysis includes an examination of the closest words to agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon in a word vector comparison via Word2Vec (Skip-Gram). Departing from the approach in the previous section, I will directly compare the word lists of both the Greco-Roman polytheistic as well as the Jewish and Christian subcorpora for each term in this part of the article.

The similarity between the word vectors in the following tables is expressed as cosine similarity. The cosine similarity can take a value between 0 (both vectors are orthogonal) and 1 (they point into the same direction, thereby indicating a strong semantic relation).

agalma

| Term | |

|---|---|

| ξόανον (wooden statue) | 0.8328 |

| ἀνάθημα (votive) | 0.8134 |

| ἀνδριάς (human-like statue) | 0.7774 |

| ἀνάκειμαι (to dedicate) | 0.7288 |

| τέμενος (temple) | 0.7240 |

| βωμός (altar) | 0.7224 |

| ἱερόν (sanctuary) | 0.7186 |

| εἰκών (eikôn) | 0.7068 |

| χάλκεος (of copper) | 0.6960 |

| ἀνατίθημι (to set up) | 0.6776 |

| Term | |

|---|---|

| ἀναίσθητος (without sense) | 0.9838 |

| ἐρεοῦς (woolen) | 0.9812 |

| ἀνδριάς (human-like statue) | 0.9810 |

| κύβος (cube) | 0.9808 |

| στιβαρός (sturdy) | 0.9808 |

| ἀνάθεσις (set up) | 0.9801 |

| ῥυθμός (measure of symmetry) | 0.9790 |

| κάλλιστα (most beautiful) | 0.9780 |

| ἄψυχος (lifeless) | 0.9776 |

| γυναικεῖος (feminine) | 0.9775 |

The comparison of the two word lists displays significant differences between the closest words to agalma according to the word vector analysis. The word list deriving from the Greco-Roman polytheistic corpus mostly includes objects, adjectives related to materiality, and various words related to statues and images, which often have a religious connotation. These words thereby underline the descriptive character of agalma already outlined in the previous parts of this article. The closest word is ksoanon with a cosine similarity of 0.83, which indicates a close semantic relation between both terms.

The word list from the Jewish and Christian corpus also includes words that stem from the semantic field of materiality. Yet, there is a more reflected perspective at play, since the mere materiality is further associated with “lifelessness” and “insensibility.” Particularly the term anaisthêtos is very close with a cosine similarity of almost 1 (0.98). Consequently, the material character of an agalma is also evoked in the Jewish and Christian corpus, but it is interpreted negatively and with a strong emphasis on the lifeless character of material images. Lastly, it is noteworthy that only one other term for statues appears in the Jewish and Christian list, namely andrias. This hints at a more differentiated use of terms related to images than it was the case in the pagan subcorpus, where most of these terms, such as andrias, ksoanon, or anathêma were used interchangeably, at least according to the word vector analysis.

eikôn

| Term | |

|---|---|

| ἀνδριάς (human-like statue) | 0.7655 |

| ἄγαλμα (agalma) | 0.7068 |

| ἐπιγραφή (inscription) | 0.6743 |

| ἐπίγραμμα (inscription) | 0.6709 |

| ἀνατίθημι (to set up) | 0.6378 |

| ἀνάκειμαι (to dedicate) | 0.6363 |

| χάλκεος (of copper) | 0.6339 |

| ἀνάθημα (votive) | 0.6167 |

| γραφεύς (painter/writer) | 0.5934 |

| ξόανον (wooden statue) | 0.5907 |

| Term | |

|---|---|

| εἴδωλον (eidôlon) | 0.9275 |

| μίμημα (copy) | 0.9244 |

| γλυπτός (carved) | 0.9187 |

| θυμία (incense) | 0.9146 |

| μεγαλεῖος (big) | 0.9110 |

| ὁρισμός (limitation) | 0.9094 |

| ὀρθόω (to set upright) | 0.9089 |

| λειτουργικός (ministering) | 0.9087 |

| ἀναστροφή (conversion) | 0.9047 |

| χρυσοχόος (goldsmith) | 0.9017 |

The closest terms to eikôn in the full Greco-Roman polytheistic subcorpus are, similarly to the observations in the case of agalma, related to statues and materiality. However, nouns connected to “to write/draw” (graphein), such as writer or inscription, are present as well. These words did not appear among the top entries of either the collocation analysis or the word frequency lists. They point to the important interplay between images and writing, for instance on the basis of a statue. A typical example of such an epigramma is given in the following quote from Pausanias:

γέγραπται δὲ ἐπὶ τῷ τοίχῳ γράμμασιν Ἀττικοῖς ἔργα εἶναι Πραξιτέλους. τοῦ ναοῦ δὲ οὐ πόρρω Ποσειδῶν ἐστιν ἐφ᾽ ἵππου, δόρυ ἀφιεὶς ἐπὶ γίγαντα Πολυβώτην, ἐς ὃν Κῴοις ὁ μῦθος ὁ περὶ τῆς ἄκρας ἔχει τῆς Χελώνης: τὸ δὲ ἐπίγραμμα τὸ ἐφ᾽ ἡμῶν τὴν εἰκόνα ἄλλῳ δίδωσι καὶ οὐ Ποσειδῶνι.

[Hard by is a temple of Demeter, with images of the goddess herself and of her daughter, and of Iacchus holding a torch.] On the wall, in Attic characters [grammasin Attikois], is written that they are works of Praxiteles. Not far from the temple is Poseidon on horseback, hurling a spear against the giant Polybotes, concerning whom is prevalent among the Coans the story about the promontory of Chelone. But the inscription [epigramma] of our time assigns the statue [eikona] to another, and not to Poseidon. (Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.2.4)

Yet, most of the terms listed in the eikôn table of the Greco-Roman polytheistic subcorpus have a relatively low cosine similarity, at least compared to the cosine similarity in the other tables. This indicates that there is an observable but relatively vague connection between the field of writing and images, which differs in its significance from the strong relation between eidôlon and eikôn in Table 4.

The closest terms to eikôn in the Jewish and Christian subcorpus are more difficult to interpret. The appearance of eidôlon as the closest term is a good example of the necessity of complementary qualitative examinations in a mixed-methods approach. Even though the term eidôlon is indeed used in a close interplay with eikôn, particularly in Clement of Alexandria, both terms have crucial differences in meaning in the Jewish and Christian subcorpus which are not directly visible when only considering the word vector analysis.

Notably, some other words are also related to the materiality of the objects (such as “goldsmith” or “carved”), but most words refer to more abstract concepts, such as mimêma (“copy”), horismos (“limitation”), and anastrophê (“conversion”), indicating the complex use and meaning of the terminology in the Jewish and Christian context (which is, particularly in a Christian context, still based on ancient discussions, since terms such as mimêma were already found in Plato’s discussions of eikôn).

Interestingly, only few of these terms and subjects were part of the collocation analysis or word frequency lists. The word vector analysis thus adds a valuable layer to the overall examination by revealing relations that were otherwise not visible.

eidôlon

| Term | |

|---|---|

| φάντασμα (phantom) | 0.7586 |

| ἀμυδρός (obscure) | 0.7220 |

| κάτοπτρον (mirror) | 0.7193 |

| μορφή (form) | 0.7063 |

| ὅρασις (seeing) | 0.7016 |

| ὁρατός (visible) | 0.6840 |

| μίμημα (copy) | 0.6745 |

| φαντάζομαι (appear) | 0.6715 |

| ἄμορφος (shapeless) | 0.6676 |

| χρῶμα (skin/color) | 0.6650 |

| Term | |

|---|---|

| βδέλυγμα (abomination) | 0.9689 |

| γλυπτός (carved) | 0.9447 |

| μίμημα (copy) | 0.9321 |

| εἰκών (eikôn) | 0.9275 |

| θυμία (incense) | 0.9267 |

| ὀρθόω (to set upright) | 0.9267 |

| ἄφθαρτος (undecaying) | 0.9263 |

| ὑπερηφανία (arrogance) | 0.9255 |

| ἀνεξιχνίαστος (inscrutable) | 0.9249 |

| ἀτιμία (disgrace) | 0.9232 |

The terms in both word lists representing the closest terms to eidôlon in both subcorpora resemble the outcome of the collocation analysis. Yet, they also include words that appeared in neither the frequency lists nor the collocation analysis. Similar to the words in Table 3, the words in Table 5 only have relatively low cosine similarity scores, thereby indicating a more distant connection in meaning (at least according to the Word2Vec analysis).

The words closest to eidôlon in the Greco-Roman polytheistic full text subcorpus are mainly concerned with different modes of visibility, with a dominating connotation of rather negative phenomena such as “shadow” and “obscure.” The words in the list from the Jewish and Christian subcorpus underline the negative character of the eidôla in the Jewish and Christian texts, where words such as “abomination” (bdelygma) or “disgrace” (atimia) are used similarly to eidôlon.

Word2Vec Summary

The comparison of the word lists from the word vector analysis revealed interesting additional insights into the use and meaning of agalma, eikôn, and eidôlon. Most intriguing was the frequent appearance of words related to graphein in the context of eikôn, thereby pointing out an observable interplay between writing and images. This observation that was not visible in the other examinations fits perfectly to the previous hypothesis that the eikones are more concerned with “what is represented” (and thus also referenced through text) than the other terms (such as agalma). It also demonstrates that “what is represented” is not always sufficiently visible in the images but might need to be addressed separately (among others, to avoid ambiguous attributions).

The analysis of the word lists from the word vector examination also resulted in additional words absent in the other examinations. These words, however, pointed into a similar direction as the words from the previous examinations (such as materiality), which can rightfully be taken as a proof that the combination of several quantitative (and qualitative) methods delivers the best results since each method helps to complement the shortcomings of the others.

Conclusion

The results of the quantitative and qualitative analyses of the Diorisis Ancient Greek Corpus in this article were able to relate to central points of the ongoing debates on the use and meaning of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn (see section 2). Particularly the quantitative analysis highlighted important notions and subjects via a transparent and empirically based methodology, thereby complementing and partially also elaborating on the understanding of the terms in question. In addition, the detailed quantitative and qualitative analyses were also able to shed new light on some details often neglected in the existing overviews of the terminology, for instance, the ambiguous application of eikôn in Jewish and Christian texts. Therefore, I hope to have shown that the application of quantitative computer-driven methods is not only useful in the context of new research questions, but that it can also help to rethink and re-evaluate the state-of-the-art of much debated topics.

Regarding the question of inter-religious contact, the results of the examinations in this article have underlined the complex interrelations of the terminologies between different religious traditions. First and foremost, the Christian traditions did not use or invent a new terminology for images, but they built their evolving taxonomy based on existing word fields. The quantitative and qualitative analyses of the various subcorpora resulted in a detailed tracing of semantic changes between the Greco-Roman polytheistic as well as Jewish and Christian uses and meanings of agalma, eidôlon, and eikôn. Among others, these changes concerned the topic of materiality and shifts between anti-iconic and iconic modes.