Neither Zarathushtra nor Pope

Anti-Catholic Polemical Fragments in the Early Study of Zoroastrianism

This paper scrutinizes how three seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century authors associated with the Anglican Church—Henry Lord, Thomas Hyde, and Humphrey Prideaux—inserted their understanding of the teachings of Zoroaster and the religion of the Parsis into the argumentative arsenal they regularly employed against what they perceived as the rigidity, excessive ritualization, and incomprehensible language found in contemporary Roman Catholic practices. These authors are tied to and reflect the consolidation of the Anglican Church and British colonial expansion. The two processes not only overlapped for a considerable period, but were also entangled, indirectly leading to an increase in scholarly knowledge about different cultures and religious communities, while in the long term also providing discursive ammunition against the Catholic Church and the Pope. This enquiry seeks to contribute to a better understanding of an often-neglected middle ground between inter- and intra-religious debates, on one hand, and missionary activity, on the other.

Anglican Authors, Zoroastrianism, Anti-Catholic Polemics, Colonialism

Introduction

To the sensibilities of a contemporary reader, a build-up like “Zoroaster and the Pope walk into a bar” might sound like the pretentious premise for a crude joke with a predictably unsatisfying punch line. Yet, in the world of religious polemics, where there have always been few limits to how one can discredit one’s religious opponents, nothing is sacred—pun intended. Comparisons between Zoroastrians and Catholics have, at a few points during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, found their way into the Church of England’s discursive repertoire. Prior to this, the Zoroastrian creed was primarily known because of the reputation of its eponymous founder, Zarathushtra or Zoroaster. Whether admired or despised, scholars on the European continent had known of him since Classical Antiquity, although his reputation was never paralleled by any precise knowledge about his teachings. Furthermore, scholarly admiration for the ancient sage rarely extended to the living practitioners of his faith. This is illustrated by the following quote from Voltaire’s Dictionnaire philosophique portatif, in which the Parsis, the Zoroastrians of India, are condescendingly called ignorant for still preserving ‘pagan’ rituals and the worship of fire:

If it was Zoroaster who first announced this beautiful maxim: “When in doubt whether an action is good or bad, abstain” then Zoroaster was the first of men after Confucius. […] Travellers […] have taught us some things of this great prophet, by means of the Gabrs or Parsis, who are still spread in India and Persia, and who are excessively ignorant. […] For my part, I confess that I have found nothing more curious about their ancient rites than these two Persian verses by Sadi […]:

Should a Gabr kindle the sacred fire a hundred years,

The poor man is burnt when he falls in. (Voltaire 1822)1

Representatives of both humanist and Enlightenment scholarship showed a deep admiration for Zarathushtra, for different reasons. For the luminaries of the Renaissance, he was Zoroaster the sage, the ancient hermetic magician, second in fame only to Hermes Trismegistus, while for Voltaire’s own ‘Enlightened’ contemporaries he was Zoroaster the wise, who taught a universal form of ethics (Rose 2000, 57–84).

Voltaire’s entry mentions travellers bringing information from faraway lands about the actual teachings of Zoroaster: reports of direct encounters with living practitioners of the faith in Iran and India. Indeed, much of the information about Zoroaster and his teachings available in eighteenth-century Europe stemmed from travelogues. One particularly early description from a travelogue compares the followers of Zoroaster to the followers of the Roman pontiff, and this comparison found its way into more scholarly texts.

This article examines some of these comparisons in an attempt to make sense of the way they fit into the broader scholarly and colonial context of their time. The examples under scrutiny originated in the works of three loosely connected authors from the seventeenth and early eighteenth century. They are the Anglican chaplain Henry Lord (fl. 1620–1630, possibly born as early as 1563), the Oxonian librarian Thomas Hyde (1636–1703), and his younger, more traditionalist contemporary, the Hebrew scholar and churchman Humphrey Prideaux (1648–1724). As illustrated by the texts they authored, their approaches vary—as one might expect with regard to their different social positions and professional roles: Lord, serving as a chaplain to the East India Company, wrote an account of his stay in India, Hyde produced a rigorously researched scholarly work, and Prideaux wrote an entertaining text for a wider readership. What these books have in common is the fact that they explored the Zoroastrian religious tradition in juxtaposition to the Roman Catholic faith, often to the detriment of the latter. This enquiry examines these parallels in their historical context and, in turn, offers insight into the previously neglected facets of the period’s scholarly exchanges, especially those with a polemical edge. The language and internal textual logic are essential for the endeavour, but only insofar as they reveal the performative function of the texts and the associated social implications for the authors and their intended audiences. This is, therefore, not so much a study of these key characters as it is a microhistorical analysis of their reasons and motivations (Ginzburg, Tedeschi, and Tedeschi 1993).

The first part of the paper will focus on Lord, his encounter with the Zoroastrians (and also the Hindus), and the work he penned following his stay in Surat, and discusses how this work echoes some of the larger theological and political disputes of the day. The second part turns to the debates around the interpretation of ancient sources. Bridging and connecting both these parts is the culture of transmission and translation within the Protestant cultural world, and how opposition to the Pope indirectly facilitated the transmission of knowledge.

It needs to be emphasized, from the outset, that the passages under scrutiny here constitute fairly brief parts of their respective works. Nevertheless, they are representative of something more than a merely random fad in the long history of anti-Catholic literature. Travelogues are not collections of ethnological observations: their authors often introduce themselves into the narratives, either as characters or as interpreters of what is happening. The scholarly works that they inspired have their own biases. Just like there is no monolithic Oriental ‘Other,’ there is no unitary European colonial authority, but rather a diversity of actors, either individuals or factions, who position themselves over space and time within various cultural configurations. Behind each report or study of the Zoroastrians, one can almost feel how the author constantly keeps one eye on the Zoroastrian community in question and the other on the religious conflicts and struggles of the time (in the most general understanding of these terms possible).2

Anglican doctrine and authority were consolidated at virtually the same time as the empire’s colonial expansion, if we take the alleged coining of the term ‘British Empire’ by John Dee (1527–1609)—also one of the long line of scholars fascinated with Zoroaster—as a starting point for the construction of an imperial mindset (Parry 2006). Thus, the intrusion of Portuguese, Dutch, British, and other European powers into Asia provided an immense body of knowledge about thriving cultures and religions, few of which were already known from ancient sources or the vague descriptions given by mediaeval travellers. The Parsis were one such community that the Western Europeans learnt about during this time.

Finally, it should be stressed that these interactions and cultural exchanges did not and could not take place under equal material conditions and power dynamics. The texts described in this article were published at a time when European powers, be they Portuguese, Dutch, or British, were slowly but firmly imposing themselves as new rulers over different regions of India, to the detriment of the local or Middle Eastern authorities.3 This imbalance of power led to a twisted logic of inversion, meaning that the wretched material conditions imposed upon the non-Europeans came to be regarded as a perennial element of their moral and intellectual inferiority rather than a direct outcome of the aggressive politics displayed in the pursuit of imperial power.4 Our understanding of Oriental encounters and the scholarship it produced in the West only benefited from the fact that historians have become increasingly aware of the inherent biases found in their recreations of the Oriental ‘Other.’5

Henry Lord—“Two Sects schismatically violating the diuine law”

The first European to write an extensive first-hand account of the Zoroastrians was Henry Lord. In the service of the East India Company, he served as a chaplain in its factory in Surat, on the Indian West Coast, in the area commonly known as Gujarat. Apart from his two-volume work, A display of two forraigne sects in the East Indies,6 published in 1630, little is known about his life, except for the unusual and possibly incorrect detail that he was already in his sixties when he embarked on the trip to India.7

Lord’s work is a two-part account of what he thought were the major ethnic and religious groups of Surat. The first part discusses the Hindus, or “Banians,” as they were known to the Europeans at the time.8 However, judging by his description and the geographic location where he was stationed, Lord was most likely unable to distinguish the Hindus from the closely coexisting Jains.9 The second, shorter half describes the Parsis, the Zoroastrians of India. In the opening passages of the book, the dedicatory epistle to the Archbishop of Canterbury, George Abbot (1562–1633), Lord explicates his mission and motivations for preparing the text:

When any person violateth the Lawes of our dread soueraigns most excellent Maiesty, […] it belongeth to some body to attach the criminous and bring him before the higher Power, there to receiue censure and sentence according to his crime. As it is thus in causes secular, so mee thinks it seemeth but reason in causes diuine. Hauing therefore in the forrainge parts of the East Indies espyed two Sects rebelliously, and schismatically violating the diuine law of the dread Majesty of Heauen, and with notable forgery coyning Religion according to the Minte of their owne Tradition, abusing that stampe which God would haue to passe currant in the true Church: I thought it my bounden duty to apprehend them and bring them before your Grace, to receiue both censure and Iudgement. (Lord 1630, A2–A3 [The Epistle Dedicatorie])

Yet, how common was this type of dedicatory epistle, in terms of language and metaphors, for the period? A brief, selective survey suggests that it was not a necessity. The similar travelogue by one of Lord’s contemporaries, Edward Terry (1589/1590–1660), published in 1625, has a preface far less humble in tone, for example. Terry had been a chaplain in India roughly a decade before Lord10 and was a more well-established figure, so one should keep in mind that Lord’s decision may have been a matter of etiquette reflecting his social position. On the other hand, the (likely) older chaplain may simply have opted for a more ceremonious style.

Regardless of his stated intention, Lord rarely conducted himself as the textual inquisitor he purported to be, at least not in regard to the Parsis, and religious invectives are only to be found at the very end of his work. While his overall analysis of the two religious groups contains an element of moderation, it oozes with the type of European exceptionalism one might expect (see Sen and Singh 2013).11 Judging by his observations and by the fact that he was able to converse directly with the religious authorities of the two groups, we can assume that he did not cause any real trouble in Surat, nor did he disturb the locals too much with his enquiries.12

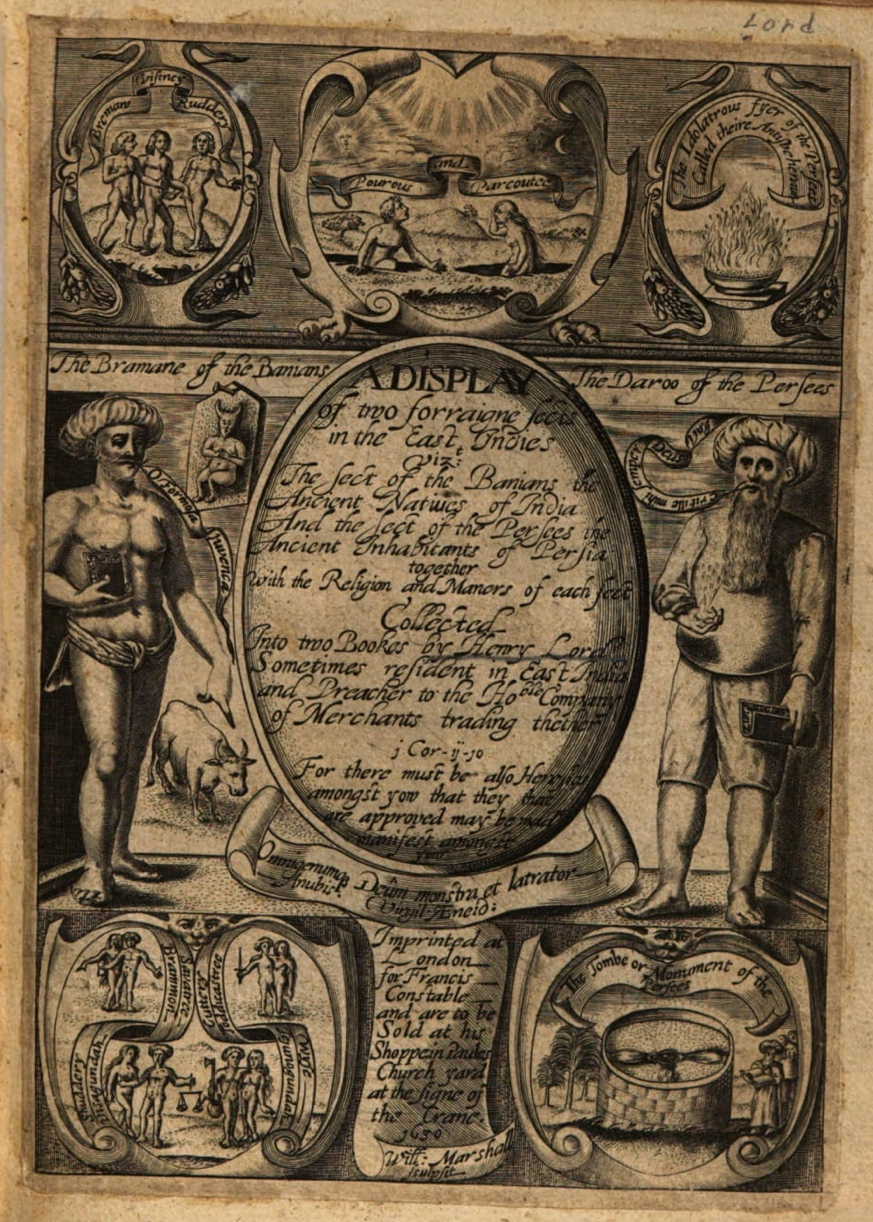

The most violent condemnation of the two sects is, perhaps, conjured by the illustrated title-page of the work itself. On the sides of the cartouche displaying the work’s title stand depicted the religious authorities of the two religions, the Hindu Brahman and the Zoroastrian Mobad, surrounded by scenes from their religious texts and traditions, including the Brahmanic creation myth and the Zoroastrian fire worship. Corresponding to Lord’s description, the Brahman appears bare-chested, pointing towards a heifer behind him, while the Mobad, dressed but bare-footed, holds the holy fire in his palm (Lord 1630, title page). Both carry their respective religious books and wear the ‘Turkish’ turban, a symbolic piece of clothing that immediately indicates that they do not belong to the Christian world (Kalmar 2005; Tischler 2015, esp 3–4). The two are surrounded by floating excerpts from their religious texts, but the selections are clearly meant to straw-man their core beliefs. The whole ensemble is framed by passages from the First Pauline Epistle to the Corinthians and a quote from Virgil, both of which explicitly condemn heretical and pagan practices.

The cover illustrates the ‘display’ aspect of the title very well, but another, slightly more subtle form of othering is implicit in the book’s name. The term ‘sects’ is demeaning to the communities described therein, since it projects an image of them as erratic religious groups, on the fringes of society and unworthy of serious consideration. Using the term ‘sect’ is not equivalent to referring to them as the secta christiana of earlier times.13 The term tended to have a negative connotation (Zinser et al. 2002; Tischler 2015, esp 7–8). In Middle English, sect denoted a non-Christian group,14 and by Lord’s time it was usual even in Latin to use the word to single out a group as less worthy of consideration, as in the merism “Christianorum fide et Turcorum secta.”15 Lord or some anonymous editor’s decision to use it in this title is obviously deliberate, as the chaplain had no problem describing them as “religions” or “faiths” elsewhere in the text (Lord 1630, The Banians: 39, 43, The Parsees: 1, 10, 52, to name only a few). The intended message was conveyed not only linguistically, but also graphically, as the title itself formed the centrepiece of the book’s frontispiece (see figure 1).

What about the use of the term ‘religion’ throughout Lord’s work? A telling example of how Lord employed this term is also found in the passage quoted above in the interesting metaphor comparing the creation of religion by the Hindus and Parsis to the minting and circulating of fake currency. The argument that they “produced” religion according to their own traditions implies that, for these groups, tradition precedes religion. While their customs might thus date back to ancient times, the religious traditions they fashioned out of them are a more recent invention, created according to the human mind and therefore not divinely sanctioned. This allows Lord to scrutinize their teachings in order to discover more about the two archaic communities, while still avoiding attributing any merit to their theology, religious ethics or institutions.

Going even further, what does ‘religion’ entail in this context, and how is it different from ‘tradition’ or other, similar concepts, such as ‘faith’? Lord wrote his book during a time when the evolution of the term ‘religion,’ in its modern sense, was still in progress and represented the object of countless debates—not that there is a definitive, clear-cut and uncontroversial definition today. In order to understand what religion entailed for Lord and his readers, we have to consider, above all, how it was correlated with salvation as this was what made a religion ‘true’ according to mainstream Anglicanism at the time (Harrison 1990, 3, 19–25). In fact, Lord’s passage seems to clearly echo the definitive word on matters of doctrine during his times found, at least for someone ranking in the lower half of the Church hierarchy: the Thirty-nine Articles of 1571. The eighteenth article states:

They also are to be had accursed that presume to say, That every man shall be saved by the law or sect which he professeth, so that he be diligent to frame his life according to that law and the light of nature. For Holy scripture doth set out to us only the name of Jesus Christ, whereby men must be saved. (Ferrell and Cressy 2005, 74)

This is a clear repudiation of the contemporary defenders of ‘natural religion’ and those who argued that it could be possible for pious non-Christians to attain salvation (Harrison 1990, 5–18, 19–22).

However, as previously mentioned, Lord’s text itself never reaches this level of explicit hostility towards either of the communities. The volume on the Hindus offers a few disparaging remarks in passing, but the one on the Parsis is never directly judgemental. In fact, the only point where Lord felt the need to ‘correct’ the people of India was when he described the interconnected prohibition that the Hindus observed with regards to killing or eating living creatures and the consumption of alcohol or wine.

The principall part of their Law admitting nothing prodigious to opinion, we passe ouer, onely that which commeth into exception […]. First, that no liuing creature should be killed. Next, that they should not taste wine, or the flesh of liuing creatures. Concerning the first […] the reason by which they confirme this precept, is because it is endued with the same soule that man is. (Lord 1630, The Banians: 45)

Lord’s problem with this is not the practice of vegetarianism itself (Gilheany 2010, iii–xiii), although this had long been associated with the type of extreme asceticism that might lead to one being labelled a heretic, as was, for example, the case with the Cathars several centuries earlier (Feuchter 2017). It should be pointed out that scholars have attempted, rather unconvincingly, to trace European Catharism back to ancient Persia for centuries, via Manicheism and its connection to Zoroastrianism.16 At the same time, there exist considerable differences between the vegetarian practice ascribed to the Cathars and that described in Manichean sources (BeDuhn 2001). Yet Lord does not find anything similar to criticize in the nutritional habits of the Parsis and it appears that his issue with Hindu vegetarianism was not the moral fibre of those who abstain from certain foods and drinks. Rather, he was troubled by what he perceived to be the consideration behind these dietary restrictions, namely their belief in the transmigration of souls. As such, he focuses on dispelling this belief and to this end invokes page after page of witnesses, even Pythagoras and Seneca, in his attempt to demonstrate that the ancestors of the Hindus did, in fact, consume meat (Lord 1630, The Banians: 45–56).

Apart from these contentious passages condemning the nutritional habits of the Hindus and the submissive, personal tone of the dedicatory epistles, Lord’s work is mostly a descriptive, almost ethnographic, account: The prose flows from one topic to the next, covering diverse matters such as dress habits, rituals, festivals, myths, and beliefs without the author explicitly intervening and telling his readers how they should think and feel about what is being depicted. The only other time Lord engages critically with the subject matter is near the very end of his volume on the Parsis. He opens the concluding passages by inviting his reader to be the one that judges the religious teachings and traditions of the Zoroastrians of India:

Such in summe (worthy Reader) is the Religion which this Sect of the Persees professe, I leave it to the censure of them that reade, what to think of it. This is the curiosity of superstition, to bring in Innovations into Religious worshippe, rather making devises of their owne braine, that they may be singular, then following the example of the best in a solid profession. What seeme these Persees to be like in their religious fire? but those same Gnats, that admiring the flame of fire, surround it so long, till they prove ingeniosi in suam ruinam, ingenious in their own destruction. (Lord 1630, The Parsees: 53)

This rhetorical device empowers Lord: he does not pass judgment on the heathens directly, but rather acts as a guardian of faith and offers his readers the hollow choice of scrutinizing the Parsi religion. It also serves as a defence before his fellow churchmen or potential rivals, allowing him to claim that he had returned from his journey to India unscathed, steadfast in his orthodoxy. Along with the dedicatory epistles, this final passage can be seen as safeguarding his reputation for any future employment or, if he was indeed venerably old at the time, for a peaceful retirement.

This latter function becomes especially evident in the second part of his conclusion, in which Lord extends the literary trial to include the Hindus. Only then does he awkwardly present a new target for his invectives, one that he most likely perceived as a more immediate threat, the Roman Catholic Church:

And if the Papists would hence gather ground for Purgatory, and prayers for the dead, and many other superstitions by them used, to bee found in these two Sects, wee can allow them without any shame to our Profession, to gather the weedes of superstition out of the Gardens of the Gentile Idolaters. But the Catholike Christian indeed, will make these Errours as a Sea marke to keep his faith from shipwracke. To such I commend this transmarine collection, to beget in good Christians the greater detestation of these Heresies, and the more abundant thanksgiving for our Calling, according to the aduise of the Apostle […]. (Lord 1630, The Parsees: 53–54)17

This convoluted metaphor likens the beliefs of the Hindus and Parsis to the alleged superstitions observed by the followers of the Papacy, going as far as to imply that the latter might even consider adopting some of them. But who is the ‘Catholike Christian’ in this context? Lord remains ambiguous, as he is most likely not referring to the Roman Catholic Church (whose adherents are addressed as “Papists”) but to his fellow countrymen in the Church of England and all those who embraced the Reformation in any of its forms. In other words, he uses Catholic in its original meaning, therefore addressing all righteous Christians. This could arguably also include those Roman Catholics who refused to take part in the ‘cult of the Papacy,’ or at least the straw man depiction of such a cult as it was fashioned by the Church of England. The mention of purgatory and prayers for the dead had little to do with Zoroastrianism or any of the other religions of India (although obvious parallels and similarities can, of course, be analysed from the point of comparative religious study). Rather, they were symptomatic of the Church of England’s own existential dilemmas during its formative years.

To better understand this point, it would help to think of the Church of England more as an institution than a confession, one for which dissent over the matter of Purgatory constituted a formational feature. The first doctrinal steps towards separation from the Roman Catholic Church were taken in 1536, with the adoption of the Ten Articles as a rushed compromise between the Catholic and the reformist camp (Douglas 2011, 1: The Reformation to the 19th century:234–35; Marshall 2010, 64–68; Ferrell and Cressy 2005, 19). The belief in Purgatory and the concept of prayers for the dead were still present in this document, although their validity was deemed uncertain:

Of purgatory: […] it is a very good and a charitable deed to pray for souls departed […] and […] it standeth with the very due order of charity […] but forasmuch as the place where they be, the name thereof, and kind of pains there, also be to us uncertain by scripture; […] Wherefore it is much necessary that such abuses be clearly put away, which under the name of purgatory hath been advanced, as to make men believe that through the Bishop of Rome’s pardons souls might clearly be delivered out of purgatory […]. (Ferrell and Cressy 2005, 25)

This solution was short-lived, and the problem of Purgatory would be more decisively settled in a document which is, ironically, otherwise infamous for its conservative nature, the King’s Book of 1543 (Marshall 2010, 77–79).18 The small differences between the book’s final chapter and the tenth article carried a heavy doctrinal weight. The title, for instance, was changed from Of purgatory to Of prayers for soules departed, and the closing passage stated that:

it is moch necessary, that all such abuses as heretofore have been brought in, by supporters and maintainers of the papacye of Rome, and their complicies, concerning this matter, be clearly put awaye, and that we therfore abstain from the name of purgatory, and no more dispute or reason thereof. (The King’s Book: A Necessary Doctrine and Erudition for Any Christen Man 1543, 232–34 [unnumbered])

This position is more vehemently affirmed in what can be considered the definitive version of the articles of faith, the aforementioned Thirty-nine Articles, which stated:

Of purgatory: The Romish doctrine concerning purgatory, pardons, worshipping and adoration, as well as of Images as of relics, and also invocation of saints, is a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of scripture, but rather repugnant to the word of God. (Ferrell and Cressy 2005, 75)

In spite of this, the promulgation of the Articles was not the final word on the matter, at least not in practice. One can still find prayers for the dead in works by Church officials, for instance in Bishop Lancelot Andrewers’s (1555–1626) popular collection of Private Prayers (Dorman 1998).

The complete purge of Purgatory from the Church of England’s theological body, it needs to be emphasized, was not a linear, gradual, or, for that matter, a definitive process (Marshall 2010, 139–41). The issue becomes even more complex if we attempt to trace a similar evolution of the changing attitudes towards prayers for the dead (Korpiola and Lahtinen 2015), which was not explicitly condemned in any major document. Suffice it to say that by the time of Lord’s stay in Surat, both the belief in Purgatory and prayers for the dead were commonly associated with support for the Papacy. If Lord was indeed born as early as 1563, he would have been part of the first few generations of clergymen schooled in the definitive version of the Anglican doctrine. In turn, as we have seen, the influence of this doctrine was strengthened in the fragments of his work that deal with Purgatory by the echoes of the Thirty-nine Articles and the more discreet references to the impossibility that other creeds could lead to salvation. By the time Lord travelled to India in 1620, few if any of the people that experienced the long and troubled rupturing of relations between the Church of England and the Papacy would have still been alive. As such, Lord’s role as a chaplain made him more than a public servant for the divine. He was a rank-and-file propagandist for the Anglican Church and, as such, he needed to safeguard its doctrines, whatever they might have been at the time.

Despite A Display’s apparent domestic commercial failure, it was translated into French in 1667 as Histoire de la religion des Banians: Avec un traité de la religion des anciens Persans ou Parsis (Lord 1667). The translator, Pierre Briot, is even more enigmatic and obscure than Lord, but a few insights can be gleaned from the way he arranged this translation. Unsurprisingly, the concluding passages refuting the Catholic creed were excised in their entirety, since they would have offended many readers, yet no counter-criticism of the Anglican Church was put in its place. In fact, Briot is quite appreciative of Lord and his method:

Mister Lord is the only one who has applied himself with care over the course of eighteen years of stay in Suratte, to know in depth the belief of these people, & of certain other Idolaters, who adore the Fire […] He had all the qualities necessary to accomplish this with dignity; he was learned & curious […]. By his means he had very particular discussions with the Bramanes of the Banjans, & with the Daros of these fire-worshipping Persians. (Lord 1667, ij–iij [Preface])

Was this an honest appreciation or a sleazy sales pitch? Since we know so little about Briot, one can only speculate, but it seems very likely that he might have been a member of France’s declining Huguenot community. This seems particularly likely if we consider some of the other texts he translated into French, especially the book on Ottoman history by Paul Rycaut (1670), the son of a Huguenot refugee in England (whether Rycaut himself identified as such is a different matter). Yet what is even more telling is the fact that this book was republished only a year later in Amsterdam. From that point on, all other translations attributed to Briot were published in the Netherlands, suggesting that he fled France to escape persecution. Another Huguenot refugee in the Netherlands, the proto-Enlightenment philosopher Pierre Bayle (1647–1706), was also familiar with Lord’s book—it is one of only two contemporary works he quotes in his pages on Zoroaster (1702, 3080–3), the other being the work of Hyde. While this does not constitute definitive proof that Lord’s text was circulating in the Huguenot intellectual milieu, it is proof that his work did have a transnational audience.

In the end, what happened to Lord after he published his only known work? Did he enjoy a peaceful retirement or, presuming he was not as old as previously thought, was he promoted to a safe position within the Church of England? Did he even return to England, or did he spend his remaining days in India? The only appropriate answer at this time is that we do not know. He is never mentioned again in any surviving contemporary records.19 However, his book eventually gained recognition within the emerging field of Oriental or Persian studies (which today we would call Iranian studies). The remainder of this paper focuses on the two scholars who made use of Lord’s observations in this context.

Thomas Hyde and Humphrey Prideaux—Oxonian Strife

For a generation, Lord’s travelogue fell into obscurity. Yet it was re-elevated above the status of historical curio eventually, around the turn of the eighteenth century, when it attracted considerable attention, namely from the aforementioned Pierre Bayle and the Oxonian Librarian Thomas Hyde (1636–1703). For better or worse, Hyde, along with his younger colleague and bitter rival, Humphrey Prideaux (1648–1724), both left their mark on the study of ancient Iranian culture and society in their own unique ways.

Hyde’s work represented a step towards the institutionalization of the study of pre-Islamic Iran, while Prideaux echoed Lord’s combative idea of looking for textual ammunition against the Roman Church (and other contemporary religious rivals) in the teachings of the ancient faiths. The two scholars were connected by their Oxonian background and a strong dislike—at least on a textual level—for the Roman Catholic Church.

Within the contemporary Republic of Letters and the emerging intellectual networks of Oriental studies focusing on Iran, Hyde was and remains a divisive figure.20 Judging him solely on the merits of his impressive list of titles, publications, and offices or by the nearly hagiographical depictions passed down by his contemporaries and followers,21 we might be tempted to see him as some sort of Renaissance man at the dawn of the Enlightenment. This image shatters once we remember that the era had no shortage of polymaths as well as quacks, ranging from Bayle or Hyde’s senior supervisor Edward Pococke (1604–1691) to Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) and Thomas Browne (1605–1682), to name only a few (Levitin 2015, 44, 82–89, 95–109).

Hyde’s relationship with the Roman Church was not always one of simple, direct antagonism. In addition to his long tenure as the Bodleian’s Librarian, he was the court interpreter for three kings, including the Roman Catholic monarch James II (r. 1685–1688). While his unique skills might have been the reason why he kept his position, it seems more likely to be the case that Hyde simply avoided courtly intrigue, particularly the type that caused religious tension. The chronology of his texts seems to support this hypothesis, as the earliest work in which he clearly expressed anti-Catholic sentiments was published one year after James I’s deposition. The work in question was a short introduction to his English edition of Alī Ufqī’s explanation of Islam, which Hyde translated under the title, the Turkish Liturgy.22 There, in one swift blow, he repudiated both Islam and Roman Catholicism:

Since therefore we have these Accounts from a Mahometan, we may believe the Relation to be just and true; especially since he discovers their Folly so freely […] and gives us Christians Occasion to laugh at their Mysterys. […] a view of their Nonsense and Folly (as likewise that of the Papists) may be a Means of confirming all others more strongly in the true Religion: for almost all their Ceremonys, especially those of Mecca, are plainly ridiculous and superstitious. (Bobovius 1712, 106–8)

Hyde’s day to day positions were more flexible. For example, in order to pursue his studies, he was more than willing to collaborate with the Jesuits. Thus in 1688, a year before publishing the preface quoted above, he invited Michael Shen Fuzong, a Chinese convert to Roman Catholicism who later joined the Jesuit order, to Oxford, where the two conversed in Latin (Poole 2015). Similarly, Hyde’s attitude towards the Zoroastrian ranged from cautiously optimistic to openly apologetic. For instance, in a letter from 1701, addressed to a captain in service of the East India Company, Hyde wrote:

When any ship is bound for Surat or Bengale, I desire to know it. […] And the same request I have at [the town of] Surat […] to get the old Persees vocabulary by which they do teach their children. But they being very close and not apt to impart anything, this must be done by a little Bribing one of their Priests with a little money, and telling him its for me who is a great lover of their Religion.23

The display of colonial mentality aside, is this pure cynicism on Hyde’s part? Regardless of his scholarly obsessions, he did not hesitate to show his admiration for the Zoroastrian religion, an appreciation which is close to the core of his magnum opus, the Historia religionis veterum Persarum,24 which was published only a year before he sent the above letter.

It is obvious that Hyde spent many years carefully researching the religion and articulating his own theories: he was the first modern scholar to study the religious sources actually produced by the Parsis and not just third-party testimonies. Nevertheless, most of these were relatively recent texts written in Farsi, not the older Pahlavi or Avestan texts. He did make some progress in deciphering the Pahlavi texts in the Avestan script but only on a very rudimentary level. Several manuscripts from India, now in possession of the British Library, still bear his notes and observations or those of his associates on their margins.25

The narrative which he meticulously constructed in his opus magnum is not always internally coherent or unambiguous, as he enriched his own novel translations and interpretations of Zoroastrian texts with biblical passages, classical writings, and mediaeval Persian and Arabic accounts. However, an idea lies at the very core of his book that can be summarized as follows: the teachings of the ancient Persians were, quintessentially, divinely revealed, and therefore close to the primordial Christian faith (Hyde 1760, Praefatio). Yet while this belief was initially perfect, it was corrupted following generations of practice and then eroded by the (Biblical) Sabeans, whom Hyde blames for the institution of fire worship (1760, 3–11). Zoroaster was, therefore, not the original teacher of the faith, but rather its reformer, a learned man who, Hyde suggests, had visions–although he was not a true prophet because his visions were not divinely sanctioned. However, given that his worldview and writings were influenced by his contact with the teachings and prophets of the Old Testament, he superimposed their ideals over his own visions, which led him to reform the religion (which would henceforth carry his name) in a manner that brought it closer to the ancient orthodoxy (1760, Praefatio [esp. unnumbered 5–6]). Hyde also cites testimony from several sources to reinforce the idea that Zoroaster was in contact with some of the Old Testament prophets (1760, 30, 292–94, 318). In other words, Hyde used a form of the centuries-old trope that “God moves in mysterious ways,” meaning that the human mind is not able to comprehend divine reasoning.

In regard to the contemporary status of the faith and its continuity, Hyde quotes several European travellers while giving special attention to Lord, albeit not without challenging some of his observations in order to fit them into his new theological and philosophical narrative (1760, 165, 314, 374, 576–77). The book also provided a lengthy apologetic, defending the Zoroastrian clear-cut separation between good and evil, contrasting it to the condemnable teachings of the Manicheans and other related heretics. For example, he also names the Cathars, although the fact that he mentions them alongside the Macarios [sic] (he most likely meant the Mattarios, as he was referring to the writings of Augustine) implies that he is talking about the ancient heretics rather than the mediaeval group. Hyde coined the term ‘dualistas’ for such groups (“…populum vero, qui credit in Prophetiam Abrahami, esse Dualistas, qui asserunt Lucem et Tenebras…”) (1760, 31, 162, 284, 288), a terminus technicus still used and abused by scholars to this day. Pierre Bayle, in particular, did not find this argument particularly enticing and criticized it a few years later for twisting or neglecting some of the well-known accounts of ancient authors (1702). Although Bayle depended on Hyde for the Persian and Arabic sources, he remained a strong opponent of any law that upholds two primary principles and, therefore, challenged the idea that Zoroaster preached a form of monotheism.

Taken out of context and in purely theological terms, Hyde might appear to be walking a fine line between the acceptable and the heretical. On the other hand, it could be said that he was simply continuing the Renaissance ‘project’ of salvaging the wisdom of Classical Antiquity. By presenting his investigations as scholarly discoveries and connecting them to the field of Old Testament history, he removed most of the elements that could have sounded controversial. Furthermore, Hyde carefully alternated between calling Zoroaster a false prophet, a prophet of the Persians, or their lawgiver, therefore maintaining a distance between the ancient Iranian and canonical prophets.26

The Historia religionis veterum Persarum became a seminal work that was widely read, applauded, and criticized on the Continent. For the next seventy years, French scholars, in particular, engaged critically with it, as in the extreme case of Abbot Foucher, one of Hyde’s fiercest posthumous opponents. Foucher criticized the book in several treatises he wrote for the Histoire de l’Académie royale des inscriptions et belles lettres, disparagingly concluding that “the learned Englishman could not have taken on a worse cause, nor defended it more poorly” (Foucher 1764). Polemics aside, was Hyde personally enamoured with the teachings of the ancient Persian prophet or did his sympathy simply extend to any foreign creed, barring Islam, Judaism, and Catholicism? Would he have been as kind towards any of the Chinese religious systems—given he learnt about them during his meeting with Michael Shen Fuzong? His fragmentary writings are lacking in this regard, yet it should be noted that this issue was a matter of controversy for the Roman Catholic world at the time. The Faculty of Theology in Paris criticized the Chinese rites, and in 1704 (a year after Hyde’s death) Pope Clement XI condemned them against the wishes and petitions of the Jesuits (Liu 2020; Rule 1994).

This transnational scholarly state of affairs provides some much-needed context for all of the attacks that Hyde’s work endured from his posthumous critics, who surreptitiously attacked their religious adversary under the guise of scholarly criticism. Scholars like Bayle, who engaged with Hyde’s work rigorously (1702, esp. 3082), were in the minority and most of the attacks had little-to-nothing to contribute to the subject. This situation persisted until the 1770s at least, when Anquetil Duperron (1731–1805) properly translated the ancient Zoroastrian texts and provided a sound scholarly rebuttal of most of Hyde’s theories, thus rendering all counter-theories proposed by his previous critics superfluous. Anquetil frequently referenced Hyde in his translations, despite contradicting or disagreeing with him, as he considered him the only real authority on the matter at the time (Duperron 1771, 1774).

In contrast to Hyde, his contemporary Humphrey Prideaux was less concerned about the porous borders separating Zoroastrians, Catholics, and the religious systems of China. One might expect Prideaux and the Bodleian Librarian to have been ideologically close, as they were, after all, both men of the Church and Oxonian scholars. Yet contemporary sources, namely Prideaux’s scholarly work and his correspondence with his close friend and confidant John Ellis (1643–1738), a man with some political power and influence, paint a more convoluted picture.27

Prideaux’s earliest mention of Hyde occurs in a letter dated 1675, although there is nothing at this point that suggests the rivalry that was to follow a few years later. It does, however, give an impression of Prideaux’s twisted sense of humour. In a letter that could best be described as miscellaneous Oxonian gossip, he recounts, in his words, a “pleasant” (1875, 44) story that is, in reality, a horrible case of domestic abuse, when Hyde was violently beaten by his wife, who suspected he was becoming intimate with her maid: “to appease his wife (Hyde) took a formal oath on the Bible […], but, this not being sufficient to satisfy the wife, she beat him soe basely that he hath kept his chamber these two months, and is now in danger of looseing his hand, which he made use of only to defend the blows and beg mercy” (1875, 44–47).

Prideaux despised Hyde and is viciously critical of him in his later letters. Things appear to have reached a particularly tense point around 1682, when Edward Pococke fell ill. As Pococke held both the professorship for Arabic studies and the chair of Hebrew, his death or forced retirement would have vacated both, so Prideaux was hoping to gain at least one of the two. Hyde was amongst his main rivals for both positions. In another letter to John Ellis, dated October 1682, he expressed his dissatisfaction with Pococke’s secretary for having sent the Arabic texts that the professor had been translating to Hyde so that he could continue working on them. This angered Prideaux, who thought little of Hyde’s intellectual abilities beyond his skill in the Persian language:

[…] and the indignity appears the greater in that he should imploy soe egregious a donce in it as Hyde; […] for noe one that hath common sense and but the hundreth part of that skill the Dr hath been noted to have in that language but must doe better then Hyde, who doth not understand common sense in his own language, and therefore I cannot conceive how he can make sense of anything that is writ in another. And beside, he hath the least skill in this language of any that pretend to it in the University; in the Persian language he can doe something, as haveing been bred to it when young, to correct as much of the Polyglot bible as is in that language when in the presse. (Prideaux 1875, 132–33)

Pococke recovered and continued to hold both offices until his death almost a decade later. Three years after the previous letter, in November 1685, Prideaux informed Ellis again about the state of the struggle for succession. This time, he appears to have abandoned his tone of angry malcontent for one of whiny resignation: “As to Dr. Pococks place, I have no expectations of it, the Earle of Rochester haveing engaged to get it for his kinsman, and I have now noe friend that hath interest at Court soe much as to ask this for me, much lesse to obtain it against soe great an interest as that of the Lord Treasures” (1875, 144–45). The contemporary Earl of Rochester he is referring to was Laurence Hyde (1642–1711) who, as his name implies, was a relative of Prideaux’s rival.

In the end, following Pococke’s death in 1691, Hyde was offered the chair of Arabic studies, while Prideaux, who by this point had grown disillusioned with academic life and the atmosphere at Oxford, was offered the one for Hebrew, which he declined. As he wrote to Ellis in October of that year: “I nauseate that learning, and am resolved to loose noe more time upon it […] and […] I nauseate Christ Church” (1875, 150–51). By this point, Prideaux appears to have already left Oxford, since the letter was sent from Saham near Watton. Regardless of whether his bitterness towards Hyde fizzled out along with his taste for academia or not, he does not seem to have brought up the former Bodleian Librarian in his private correspondence again, at least as far as we can tell from what has been published so far. The professorship for Hebrew was awarded to Roger Altham, who resigned and was replaced by Hyde in 1697, only to resume it a few years later due to Hyde’s waning health. Thomas Hyde died in 1703. The younger Prideaux outlived him by almost two decades, a period in which he wrote his most successful works.

None of the quarrels described above can be detected when reading Prideaux’s late opus, The Old and New Testament Connected in the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations, first published in 1715 (1823).28 As the author informs his readers, the work relied heavily on Hyde for the passages dealing with Zoroaster:

What I have out of the latter, I am beholden for to Dr. Hyde’s book, De Religione veterum Persarum, for I understand not the Persian language. All that could be gotten out of both these sorts of writers [Zoroaster and Muhammad; IC] concerning him or his religion, that carry with it any air of truth, is here carefully laid together; as also every thing else that is said of either of them by the Greeks, or any other authentic writers; and, out of all this put together is made up that account which I have given of this famous impostor. (Prideaux 1823, 82–83)

A few hundred pages later, when discussing the religion, he laments the fact that Hyde was never able to complete his planned translation of the Avesta,29 the Zoroastrian scripture:

This book Zoroastres feigned to have received from heaven, as Mahomet afterwards (perchance following his pattern) pretended of his Alcoran. […] Dr. Hyde, late professor of the Hebrew and Arabic tongues at Oxford, being well skilled in the old Persic, as well as the modern, offered to have published the whole of it with a Latin translation, could he have been supported in the expenses of the edition. But for want of this help and encouragement, the design died with him, to the great damage of the learned world. (Prideaux 1823, 323)

It is quite clear that Hyde’s reputation as a master of all things Persian was, in the English-speaking world, unchallengeable at this point. However, many of the interpretations in The Old and New Testament are Prideaux’s own. The Zoroastrians are first introduced into the account midway through his reconstruction of the events surrounding the Babylonian captivity, with a mean-spirited short story about the life of Zoroaster:

In the time of his [Darius’s; IC] reign first appeared in Persia the famous prophet of the Magians, whom the Persians call Zerdusht, or Zaratush, and the Greeks, Zoroastres. […] It is certain he was no king, but one born of mean and obscure parentage, who did raise himself wholly by his craft in carrying on that imposture with which he deceived the world. (Prideaux 1823, 310–11)

This tirade was, chronologically, not the first instance of Prideaux bickering with the prophets of Antiquity. Earlier in his life he had written a joint refutatio of Islam and the deism of some of his contemporaries. This was only thinly disguised as a critical enquiry into the life and teaching of Muhammad, entitled The True Nature of Imposture Fully Display’d in the Life of Mahomet (1697).30 This book harkens back to a style of polemical writing in which the scholarly element was secondary as long as one’s target was entirely crushed using a wide range of invectives. It received criticism for adding little scholarly value, most notably from the first translator of the Qur’an into English, George Sale (1697–1736) (1734, iii). The fact that Prideaux is the only Anglican author whom Sale mentions by name and extensively criticizes is a testament to his work’s enduring popularity—this translation was published 12 years after his death.

Perhaps Prideaux thought that, having ‘refuted’ Muhammad in his earlier work, it was now time to turn to the second in this line of prophetic impostors. In fact, he suggested as much in the preface to this work, in the same passage where he discussed Hyde’s influence: “And if the Life of Mahomet, which I have formerly published, be compared herewith [the account of Zoroaster in Hyde’s work; IC], it will appear hereby, how much of the way, which this latter impostor took for the propagating of his fraud, had been chalked out to him by the other.” As such, he invented this quite peculiar origin story for the Persian prophet:

He was the greatest impostor, except for Mahomet, that ever appeared in the world, and had all the craft and enterprising boldness of that Arab, but much more knowledge; for he was excellently skilled in all the learning of the East that was in his time; whereas the other could neither write nor read; and particularly he was thoroughly versed in the Jewish religion, and in all the sacred writings of the Old Testament that were then extant, which makes it most likely that he was, as to his origin, a Jew […] by birth as well as religion, before he took upon him to be a prophet of the Magian sect. (Prideaux 1823, 310–11)

Pairing Zoroaster and Muhammad was something of an innovation, at least as far as Western Christianity was concerned.31 As mentioned above, a small but influential group of Renaissance artists and scholars had earlier been fascinated by the Persian prophet (Levitin 2015, 33–112) in his role as Zoroaster the sage (Rose 2000, 57–84), but apart from this, he had remained something of a minor malevolent figure in Christian lore, mostly associated with the invention of magic. The widespread use of this image can be traced back to Isidore of Seville’s (c. 560–636) enormously popular and influential Etymologiae (Stausberg 1998, 439–63). As such, one would expect to find him placed alongside figures such as Simon Magus rather than next to the prophet of Islam.

While Prideaux took a few artistic licenses with this story of a Jewish Zoroaster, whom he painted as a disloyal, treacherous assistant to the biblical prophets, the tale was not entirely a product of his imagination. The account was taken from De vetere religione Persarum, where Hyde quotes a similar story given by the Arabic historian al-Bundārī (fl. early thirteenth century) (Hyde 1760, 318). Al-Bundārī was most likely quoting the Perso-Arabic scholar al-Ṭabarī (839-923) (Hyde 1760, 319; Jackson 1899, 96–97), who was, in turn, relying on a now lost work by the Arabic genealogist al-Kalbī (737–819) (Büchner 1927, esp. 98). According to this account, which Hyde discusses only in passing, Zoroaster was the servant of Jeremiah, whom he deceived. As a punishment, he was infected with leprosy. In order to purify himself and cure his disease, Zoroaster went to preach a new religion in Persia, convincing the people to adore the sun instead of the stars (Hyde 1760, 318–19). Prideaux modified the last part slightly and invented an account of how Zoroaster tricked his followers into worshipping fire by claiming he had received it from heaven. Stressing the continuity of this fire worship and comparing the Zoroastrian creed once more with Islam, Prideaux informs his readers that there are still living practitioners of the faith:

He did not found a new religion, as his successor in imposture Mahomet did, but only took upon him to revive and reform an old one, that of the Magians, which had been for many ages past the ancient national religion of the Medes, as well as of the Persians […] And all [religious practices; IC] the remainder of that sect, which is now in Persia and India, do without any variation, after so many ages, still hold even to this day. (Prideaux 1823, 312–14)

Up until this point, the text’s style had no doubt been hostile towards other creeds, but it had remained a more or less scholarly attempt at reconstructing and interpreting the past. Little attention had been given to the present and even less to what was to be expected in the future. Surprisingly, however, Prideaux used this passage to digress and launch a bitter diatribe against the Roman Catholics, focusing specifically on how their contemporary observances and ritual practices created a disconnection between the officiants and the congregation:

[…] the priests themselves never approached this fire, but with a cloth over their mouths, that they might not breath thereon; and this they did […] when they approached it to read the daily offices of their liturgy before it: so that they mumbled over their prayers rather than spoke them, in the same manner as the Popish priests do their masses, without letting the people present articulately hear one word of what they said; and, if they should hear them, they would now as badly understand them; for all their public prayers are, even to this day, in the old Persian language […] of which the common people do not now understand one word: and in this absurdity also have they the Romanists partakers with them. (Prideaux 1823, 317)

Disparagingly describing one’s ritual delivery as mumbling has an older history in anti-Catholic tradition. It was used, for instance, by Dierick Ruiters, a Dutch Protestant who travelled to Western Africa (only a few years before Lord embarked on his trip to India) and wrote about the local customs he observed. Ruiters connected the mumbling officiation of a ceremony to Turkish rituals and through these to the Roman Catholics (Brauner 2017), in a similar way to how Hyde switched the focus of his text in his preface to Bobovius’s work.

Returning now to Prideaux’s paragraph, from the nature of ritual performance, he transitions to the language of the liturgy and how the Catholic Church refused to adapt to the changing socio-linguistic realities:

When Zoroastres composed this liturgy, the old Persic was then indeed the vulgar languages of all those countries where this liturgy was used: and so was the Latin throughout all the western empire when the Latin services was first used therein. But when the language changed, they would not consider that the change which was made thereby, in the reason of the thing, did require a change should be made in their liturgy also, but retained it the same after it ceased to be understood, as it was before. (Prideaux 1823, 317)

In addition to these blows, Prideaux’s polemical tangent goes as far as finding alleviating circumstances for the Persians, to the detriment of the Catholics. While this position is not unusual, it should be taken as a strong indictment of the Catholics rather than a weak excuse for the Zoroastrians. In any case, it offers a more positive outlook on the Persians than the less established Lord was willing to risk a century earlier. The entire subsection is then concluded by emphasizing the importance of vernacular liturgy:

So it was the superstitious folly of adhering to old establishment against reason that produced this absurdity in both of them: though it must be acknowledged, that the Magians have more to say for themselves in this matter than the Romanists; for they are taught that their liturgy was brought to them from heaven, which the others do not believe of theirs, though they stick to it as if it were. […]. And […] should our [English] liturgy be still continued, without any change or alteration, it will then be as much in an unknown language as now the Roman service is to the vulgar of that communion. (Prideaux 1823, 318)

Unlike the similar anti-Catholic passage in Lord’s work, this section is left intact in the French version of Prideaux’s book. This is not surprising since the translation was produced by the exiled French Protestants Moses Solanus and Jean-Baptiste Brutel de la Rivière and published in Amsterdam in 1722, as Histoire des Juifs et des peuples voisins (Prideaux 1722).32

The reference to the need to update the language used for liturgy and religious texts seems to mirror contemporary concerns within the Church of England: At the time of Prideaux’s writing, there was some dissatisfaction with the fact that the King James Version, which was over a century old by this point, had not undergone any considerable update. Its language and spellings were archaic and while printers were taking matters into their own hands and introducing changes, a new standard text would not be sanctioned until 1769 (Norton 2005, 100–102). It is not entirely clear if Prideaux was part of any group advocating for a new version of KJV, but the influence of these loose factions was only marginal at this point, despite boasting some powerful supporters (Daniell 2003, 488–89, 499–517).

Prideaux’s book was a commercial success overall, perhaps even more so than his previous book on the life of Muhammad. Unlike Hyde, he lived to see his ideas receive actual critical feedback from the international community of scholars. Many of the reviews written during his lifetime were positive. A telling example is a book-length review by Jean Le Clerc (1657–1736), a theologian, philosopher, and key figure in the Republic of Letters. Le Clerc’s survey says little about Zoroaster or about the Pope, for that matter. It also says nothing about the polemical or political dimension of Prideaux’s work, since Le Clerc treats it as a purely scholarly contribution. It is, however, representative of a contemporary way of approaching ancient material, an approach similar to how Hyde’s critics dealt with the ancient texts. Le Clerc admired Prideaux’s scholarly achievements: “this work is indeed useful to all Degrees and Conditions of Men, who would know the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations” (1722, 4).33 He also provided some comments that are useful if we want to better understand the contemporary practices of translation. Le Clerc had read the work in the Dutch version, translated by Joannes Drieberge, a Remonstrant preacher who added his own annotations, and points out that the translator “sometimes also subjoins his own Sentiments upon the Subjects handled, and does not always confine himself to subscribe to the Opinion of his Author whom he translates” (1722, 50–51).

Some of Prideaux’s interpretations were challenged by Le Clerc, who would intervene by opposing some of the more speculative assumptions and suggesting his own equally imaginative theories instead, often without offering any actual arguments (1722, 15–16). This is a far cry from the more substantive approach of Hyde or Bayle, for whom the reconstruction of Antiquity, while heavily contaminated by their personal speculations, were also heavily dependent on gathering and mastering ancient or foreign sources on the subject.

Conclusions and Avenues for Further Enquiry

If we were to search for a technical term that adequately describes and encompasses the sentiments expressed throughout the quoted fragments, we could turn to the somewhat pretentious ‘paganopapism,’ the belief or rhetorical assertion that there is little difference between paganism and Catholic worship or the attitudes towards the papacy. The term has already been used by Will Sweetman to define the type of attitude present in Lord’s travelogue (Sweetman 2003, 85–86). Since this notion is only incidental, the term does not describe the texts themselves, but rather part of the atmosphere they conjure, regardless of the actual intentions of their authors. While the aim of these scholars (apart from Prideaux, perhaps) was not to primarily attack the Roman, the anti-Papist polemic is present throughout their writings.

At the same time, there is a second possible direction of study, diachronically, approaching these works as part of the evolution of Western European knowledge and discourse about other cultures and religions, both living and dead. All of the texts described or mentioned in passing in this article represent a minuscule fraction of the body of textual material which led to the creation of Western European narratives about religious practices from across the world. In turn, the study of these distant communities is an extension of some of the narratives used when attempting to understand coexisting non-Christian communities closer to home. It would therefore prove interesting to study the tropes, biases, and discursive methods used in constructing the types of arguments found in these works.

Language and terminology are, as we have seen, an essential part of how strongly these considerations are woven into the texts themselves. Henry Lord used ‘sect’ and ‘religion’ interchangeably in his book, knowing full well how to use the imbalance between the terms. The use of ‘sect’ isolated the subject of study, pushing the community or communities described as such into a cold and sterile dimension, worth studying but not deserving an equal treatment, since belonging to a ‘sect’ implied being different and, more importantly, wrong. In the case of these Zoroastrians and the Hindus, it isolated them in a type of ahistoricity in an attempt to portray a sui generis image of the community and its religious beliefs and practices. Lord ironically suggested that the superstitions of the Parsis could be appealing to the Roman Catholics, while Prideaux, with equally bitter irony, found points in which the beliefs and convictions of the Persians were superior to the ones of the Papists. Yet, in both cases, we need to keep in mind that the Parsis are still most often called a sect, a stray religion, without any further consideration. This is opposed to the Catholics who are not as gratuitously labelled as such, so it is safe to assume that in spite of any qualities that the Anglicans might have ascribed to the Zoroastrians, a sort of religious barrier still kept them apart from the followers of Rome, who were closer to Lord and Prideaux on almost every level. Hyde attempted to circumvent this barrier and to pull the teaching of Zoroaster inside the sphere of accepted religion by bestowing merit upon it for drawing from the same source as the Abrahamic God—a merit which he clearly did not seek to claim, for instance, for Islam. At the same time, he remained ambiguous about how to approach the living practitioners of the faith, which he admitted practised a corrupted form of the religion.

The use of invectives, such as when Lord called the Parsis “gnats,” and ad hominem attacks, such as that found in Prideaux’s criticism of the use of Latin during the liturgy, is particularly interesting. Hyde uses a simplistic and unimaginative technique which can best be summed up as “let us laugh at their nonsense, and at the folly of the Papists, since they are so similar” against the Muslims, yet he never uses it against the Zoroastrians. Prideaux and Lord go a step further by inferring from the perceived similarities between Zoroastrians and Catholics a potential for disaster that might ensue if the Catholics continue to walk the same path as the Parsis, a path that would lead them even further astray than the Zoroastrians. One would expect Lord to be more incisive, given his being a chaplain, responsible for maintaining religious order in a foreign, multi-religious environment, yet his rhetorical approach is to play the role of emotionally distant prosecutor. Prideaux, however, did not hesitate to relentlessly draw from the rich Christian polemical tradition of invective tools at his disposal, be it inter- or intra-religious (Steckel 2018): from the classical accusations of false prophecy to the derision of ritual practices and the topical accusation of affiliating oneself with the Jews. In the end, despite trying to make the path of Zoroaster sound better than that of the Pope, Lord, Hyde, and Prideaux walked neither, but rather remained firmly on the safe road of Anglican orthodoxy.

References

Armitage, David. 2004. “Lord, Henry (1563 – ?).” In The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 34:437–38. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bayle, Pierre. 1702. “Zoroastre.” In Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, 3 N–Z:3077–83. Rotterdam: Reinier Leers.

BeDuhn, Jason David. 2001. “The Metabolism of Salvation: Manichean Concepts of Human Physiology.” In The Light and the Darkness, edited by Mirecki Paul and Jason David BeDuhn, 5–37. Leiden / Boston / Köln: Brill.

Bobovius, Albertus. 1712. “A Treatise Concerning the Turkish Liturgy.” In Four Treatises Concerning the Doctrine, Discipline and Worship of the Mahometans, edited by J. Darby, translated by Thomas Hyde. London: Printed for B. Lintoit.

Boyce, Mary. 1979. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London / Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Brauner, Christina. 2017. “Wie die Papisten bei ihrer Meß. Wahrnehmung religiöser Rituale und konfessionelle Polemik im europäischen Diskurs über Westafrika [Like the Papists at Their Mass. Perception of Religious Rituals and Confessional Polemics in the European Discourse on West Africa].” In Intertheatralität. Die Bühne als Institution und Paradigma der frühneuzeitlichen Gesellschaft, edited by Christel Meier and Dorothee Linnemann, 207–30. Münster: Rhema.

Büchner, V. F. 1927. “Mad̲j̲ūs.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed., III:97–102.

Daniell, David. 2003. The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. London: Yale University Press.

Dorman, Marianne. 1998. “Lancelot Andrewes and Prayer.” Project Canterbury. http://anglicanhistory.org/essays/dorman1.html.

Douglas, Brian. 2011. A Companion to Anglican Eucharistic Theology. Vol. 1: The Reformation to the 19th century. Leiden / Boston: Brill.

Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques. 1958. The Western Response to Zoroaster. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duperron, Anquetil. 1771. Zend-Avesta, Ouvrage de Zoroastre [Zend-Avesta, the Work of Zoroaster]. Paris: N.M. Tilliard.

———. 1774. “Exposition Du Système Théologique des Perses, Tiré des Livres Zends, Pehlevis et Parsis [Exposition of the Theological System of the Persians, From the Zend, Pahlavi, and Persian Books].” Mémoires de Littérature, Tirés des Registres de L’Académie Royale Des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 37: 571–754.

Fanon, Frantz. 1952. Peau noire, masques blancs [Black Skin, White Masks]. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Ferrell, Lori Anne, and David Cressy. 2005. Religion and Society in Early Modern England: A Sourcebook. New York: Routledge.

Feuchter, Jörg. 2017. “Mit Ketzern essen. Ernährungsstrategien in einer von Katharern und Waldensern geprägten Stadtgesellschaft (Montauban, Südfrankreich, 13. Jahrhundert) [Eating With Heretics. Nutritional Strategies in an Urban Society Modeled by Cathars and Waldensians. (Montauban, South of France, Thirteenth Century)].” Essen und Fasten: Interreligiöse Abgrenzung, Konkurrenz und Austauschprozesse 81: 23–50.

Firby, Nora. 1988. European Travelers and Their Perceptions of Zoroastrians in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Berlin: Reimer Verlag.

Foucher, L’Abbé. 1764. “Suite Du Traité Historique de La Religion Des Perses. Second Époque. Quatrième Mémoire [Continuation of the Historical Treatise on the Religion of the Persians. The Second Age. The Fourth Thesis].” Histoire de L’Académie Royale Des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 29: 87–141.

Gilheany, John. 2010. Familiar Strangers. The Church and the Vegetarian Movement in Britain (1809–2009). Cardiff: Ascendant Press.

Ginzburg, Carlo, John Tedeschi, and Anne Tedeschi. 1993. “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know About It.” Critical Inquiry 20 (1): 10–35.

Goodwin, Gordon. 1889. “Ellis, John (1643? – 1738).” In Dictionary of National Biography, 17:284–5. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5000 Years. New York: Melville House Publishing.

Grünpeck, Joseph. 1522. Dyalogus epistolaris, in quo Arabs quidam Turcorum imperatoris Mathematicus disputat cum Mamulucho quodam de Christianorum fide et Turcorum secta [Epistolary Dialogue in which a certain Arab mathematician of the Emperor of the Turks disputes against a certain Mamluk about the Christian Faith and the Sect of the Turks]. Landshut: Weyssenburger.

Harrison, Peter. 1990. “Religion” and the Religions in the English Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haug, Judith I. 2016. “Being More Than the Sum of One’s Parts: Acculturation and Biculturality in the Life and Works of Ali Ufukî.” Archivum Ottomanicum 33: 179–90.

Herbert, Thomas. 1677. Some Years Travels into Diverse Parts of Africa and Asia the Great. London: R. Everingham.

Hyde, Thomas. 1760. Veterum Persarum et Parthorum et Medorum religionis historia [The History of the Religion of the Ancient Persians and Parthians and Medians]. Oxford: Typographeo Clarendoniano.

Jackson, A. V.Williams. 1899. Zoroaster: The Prophet of Ancient Iran. New York / London: Macmillan.

Kalmar, Ivan. 2005. “Jesus Did Not Wear a Turban: Orientalism, the Jews, and Christian Art.” In Orientalism and the Jews, edited by Ivan Kalmar and Derek Penslar, 3–31. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press.

Kellens, Jean. 1996. “Comment Connaissons-Nous L’Avesta, Le Livre Sacré Des Mazdéens? [How Do We Know the Avesta, the Sacred Book of the Mazdeans?].” Bulletin de La Classe Des Lettres et Des Sciences Morales et Politiques 6 (7): 497–508.

Korpiola, Mia, and Anu Lahtinen. 2015. “Introduction.” In Cultures of Death and Dying in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by Mia Korpiola and Anu Lahtinen, 1–31. Helsinki: Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies.

Le Clerc, John. 1722. Critical Examination of the Reverend Mr. Dean Prideaux’s Connection of the Old and New Testament. Translated by Philalethes. London: Printed for J. Roberts.

Levitin, Dmitri. 2015. Ancient Wisdom in the Age of the New Science: Histories of Philosophy in England, C. 1640–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Liu, Yu. 2020. “Behind the Façade of the Rites Controversy: The Intriguing Contrast of Chinese and European Theism.” Journal of Religious History 44 (1): 3–26.

Lord, Henry. 1630. A Display of Two Forraigne Sects. London: Imprinted for Francis Constable.

———. 1667. Histoire de la religion des Banians: Avec un traité de la religion des anciens Persans ou Parsis [History of the Banian Religion: With a Treatise On the Religion of the Ancients Persians or Parsis]. Translated by Pierre Briot. Paris: Paris: Robert de Ninville, au bout du Pont Saint Michel.

———. 1999. A Discovery of the Banian Religion and the Religion of the Persees: A Critical Edition of Two Early English Works on Indian Religions. Edited by Will Sweetman. New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

Manselli, Raoul. 1975. “C’è davvero una riposte dell’ occidente a Zaratustra nel medioevo? [Is There Really a Western Response to Zaratustra in the Middle Ages?].” In Studi sulle eresie del secolo XII [Studies on the Heresy of the Twelfth Century], edited by Raoul Manselli, 157–72. Rome: Nella Sede dell’ Istituto Palazzo Borromini.

Marshall, Peter. 2010. Beliefs and the Dead in Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norton, David. 2005. A Textual History of the King James Bible. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Orlando, Thomas. 1976. “Roger Bacon and the Testimonia Gentilium de Secta Christiana.” Recherches de Théologie Ancienne et Médiévale 43 (January–December): 202–18.

Parry, Glyn. 2006. “John Dee and the Elizabethan British Empire in Its European Context.” The Historical Journal 49 (3): 643–75.

Poole, William. 2015. “The Letters of Shen Fuzong to Thomas Hyde, 1687–1688.” Electronic British Library Journal. https://www.bl.uk/eblj/2015articles/article9.html.

Prideaux, Humphrey. 1697. The True Nature of Imposture Fully Display’d in the Life of Mahomet with A Discourse Annexed for the Vindication of Christianity from This Charge. Offered to the Consideration of the Deists of the Present Age. London: Printed for William Rogers.

———. 1722. Histoire des Juifs et des peuples voisins [History of the Jews and the Neighbouring Nations]. Translated by Jean-Baptiste Brutel de la Rivière and Moïse Soul. Amsterdam: Henri Du Sauzet.

———. 1823. The Old and New Testament Connected in the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations. Boston: Cummings and Hilliard.

———. 1875. Letters of Humphrey Prideux to John Ellis. Edited by Edward Maunde. Westminster: Printed for the Camden Society.

Rose, Jenny. 2000. The Image of Zoroaster: The Persian Mage Through European Eyes. New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press.

———. 2009. “Zoroaster, Vii. As Perceived by Later Zoroastrians.” In Encyclopædia Iranica. Online Edition. https://iranicaonline.org/articles/zoroaster-vi-as-perceived-by-later-zoroastrians.

———. 2015. “Riding the (Revolutionary) Waves Between Two Worlds: Parsi Involvement in the Transition from Old to New.” In The Zoroastrian Flame: Exploring Religion, History and Tradition from Old to New, edited by Alan Williams, Sarah Stewart, and Almut Hintze, 295–320. London: LB. Tauris.

Rule, Paul. 1994. “Towards a History of the Chinese Rites Controversy.” In The Chinese Rites Controversy: Its History and Meaning, edited by D. E. Mungellor, 249–66. Nettetal: Steyler.

Rycaut, Paul. 1670. Histoire de l’état present de l’Empire ottoman [The Present State of the Ottoman Empire]. Translated by Pierre Briot. Paris: Impr. de Sébastien Mabre-Cramoisy.

Said, Edward. 1983. The World, the Text, and the Critic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sale, George. 1734. The Koran, Commonly Called the Alcoran of Mohammed. London: C. Ackers in St. John’s-Street.

Sen, Amrita, and Jyotsna Singh. 2013. “Classifying the Natives in Early Modern Ethnographies: Henry Lord’s a Display of Two Foreign Sects in the East Indies (1630).” Journeys 14 (2): 69–84.

Sheffield, Daniel J. 2015. “Primary Sources: New Persian.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism, edited by Michael Stausberg and Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina, 529–42. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Sims-Williams, Ursula. 2012. “Zoroastrian Manuscripts in the British Library.” In The Transmission of the Avesta, edited by Alberto Cantera, 173–94. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

———. 2013. “The Revelation of Arda Viraf.” In The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination, edited by Sarah Stewart, 141. London: LB. Tauris.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2010. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea, edited by Rosalind Morris, 21–78. New York: Columbia University Press.

Stausberg, Michael. 1998. Faszination Zarathustra: Zoroaster und die europäische Religionsgeschichte der frühen Neuzeit [Fascinating Zarathustra: Zoroaster and the European History of Religions of the Early Modern Times]. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Steckel, Sita. 2018. “Verging on the Polemical. Towards an Interdisciplinary Approach to Medieval Religious Polemic.” Medieval Worlds 7: 2–60.

Sweetman, Will. 2003. Mapping Hinduism: “Hinduism” and the Study of Indian Religion, 1600–1776. Halle: Verlag der Franckeschen Stiftungen.

Terry, Edward. 1655. A Voyage to East-India. London: Printed by T.W. for J. Martin and J. Allstrye.

The King’s Book: A Necessary Doctrine and Erudition for Any Christen Man. 1543. London: Imprinted at London in Fletestrete.

Tischler, Matthias M. 2015. “‘Lex Mahometi’. The Authority of a Pattern of Religious Polemics.” Journal of Transcultural Medieval Studies 2: 3–63.

Williams, A. V. 2004. “Hyde, Thomas.” Encyclopædia Iranica XII (6): 590–92. https://iranicaonline.org/articles/hyde.

Zinser, Hartmut, Karl Hoheisel, Manfred Hutter, Wolfgang Wassilios Klein, and Ulrich Vollmer. 2002. “Religio, secta, haeresis in den Häresiegesetzen des Codex Theodosianus (16,5,1/66) von 438 [Religio, Secta, Haeresis in The Laws on Heresy of the Codex Theodosianus (16,5,1/66) from 438].” In Hairesis: Festschrift für Karl Hoheisel zum 65. Geburtstag, 215–9. Münster: Aschendorff.

All translations by the author unless indicated otherwise. Voltaire first included this entry in the second edition, published in 1765. The dictionary’s original edition, arguably the only one that was actually portable, named Zoroaster only in passing. The mention of mediaeval Persian poet Saadi (1210–1291/1292) reflects Voltaire’s interest in Persian learned culture and its overarching evolution since the times of Zoroaster, a theme he had explored in his 1747 philosophical novel Zadig (ou la Destinée).↩︎

For the question of audience and the various levels and strata that form a text, see the later works of Edward Said, in which he rejects the earlier Foucauldian approach of Orientalism, especially Said (1983).↩︎

For an anthropological approach to the relation between the European expansion, its methods of economical domination, and the connection with social changes in Europe, see Graeber (2011, 307–60).↩︎