Leaving Javanese Shadow Theatre (Wayang Kulit) Religiously Unlabelled

The Challenge of Presenting Non-European Art in a European Museum

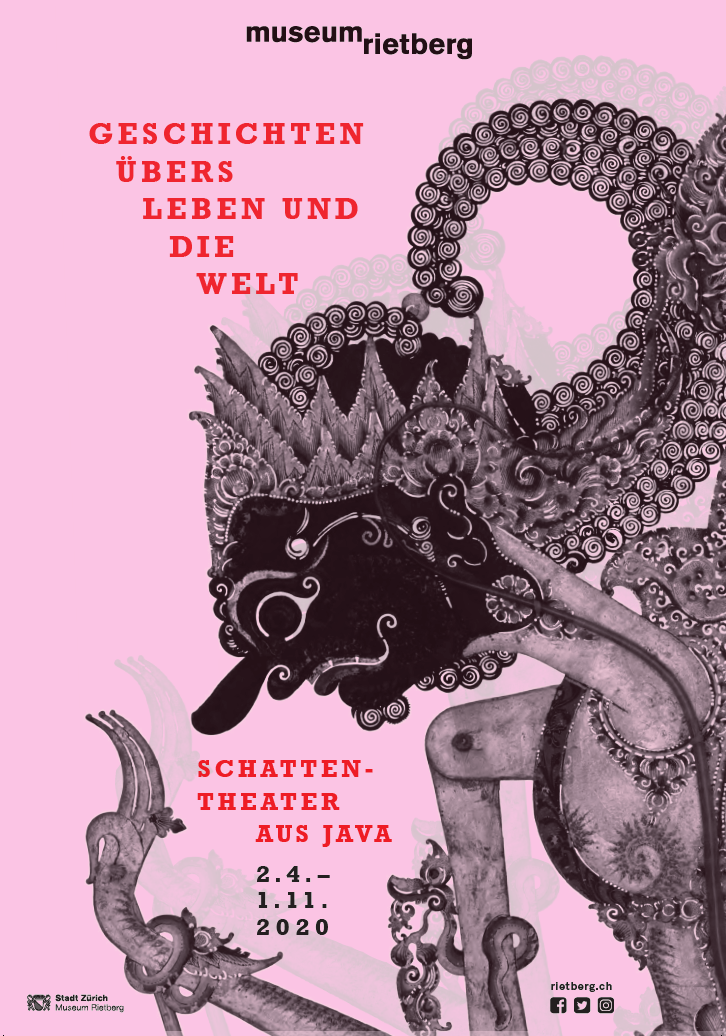

Wayang Kulit, the shadow theatre tradition on the island of Java, combines ancient Javanese and Indian myths in a Muslim context and therefore poses as a wonderful example of how religious traditions intertwine with works of art. This article explores the religious appropriation and acculturation at work in the history of Javanese shadow theatre. It also grants a behind-the-scenes look at the curatorial challenges involved in preparing a Wayang Kulit exhibition at the Museum Rietberg in Zurich, in particular how to convey the complex intermingling of cultures and religions so that audiences can understand it. Finally, we call into question some narratives and concepts traditionally used in Western museums to tell the story of Southeast Asian art.

Indonesia, Java, museum collections, curating religions, performing arts, Hinduism, Islam, Wayang Kulit, Indianization, Islamization, acculturation, shadow theatre

Introduction1

The Museum Rietberg was founded in 1952 by the City of Zurich to showcase non-European art. Its founding collection was donated by Eduard von der Heydt (1882–1964), who had bought numerous works of Asian, African, American and Oceanic art on the Western art market during the 1920s and 1930s (Illner 2013). Today, his collection of Southeast Asian art forms only a small part of the museum’s holdings (2,000 pieces of a total of 67,509 artworks). Another important donor of Southeast Asian art was the Swiss art dealer Toni Gerber (1932–2010), who acquired a huge collection of Burmese pieces on his numerous trips to Thailand. Missing from the galleries and collections of the Museum Rietberg are objects related to the Islamic and colonial history of Southeast Asia. This is because the Rietberg receives most of its artworks from donors, which has led to a certain eclecticism. Instead of applying a systematic and encyclopaedic acquisition strategy, the museum has been guided by the individual tastes and passions of its donor-collectors.

The permanent display of Southeast Asian artworks at the Museum Rietberg reveals some conceptual paradoxes and challenges. One source of confusion results from the fact that these objects have been divided into two groups: the Rietberg Beyond India (Rietberg Hinterindien, or RHI) collection, which includes all artworks from mainland Thailand, Cambodia, and the Malaysian peninsula (Fontein 2007); and the Rietberg Indonesia (RIN) collection, which includes ‘tribal’ and artisanal objects that did not fit into the category of ‘high art’. The first curator of the Beyond India collection specialised in Chinese art; the second was a curator of African and Oceanian art. A conceptual framing was thus imposed on the objects: Southeast Asian pieces were subsumed into larger collections of either Indian and Chinese ‘high’ art or Oceanic ‘tribal’ art. This framing is still manifest in the permanent galleries, which are arranged according to geography and region. The ground floor of the Villa Wesendonck houses Indian and Tibetan sculptures, while the first floor is dedicated to ‘tribal arts’ from the Malayan peninsula, Oceania, and the Americas. The spectacular objects from mainland Southeast Asia, such as those from Angkor, are placed in between. Visitors can admire them along the beautiful staircase of the villa. Interestingly, the display on the staircase to the second floor can be interpreted as a metaphor for transition, because the objects originate from locations between South Asia and the islands of Oceania.2

Over the last decades, the arts of the Malay Archipelago have been highlighted in several special exhibitions at the Rietberg. In 1982, the museum mounted an exhibition called Materials on Javanese Rod Puppets, curated by Walter Gamper, one of the major collectors of Indonesian Wayang Golek puppets. It featured loans from his private collection, one of the largest in Switzerland, which has now been given to the Museum der Kulturen in Basel (Gamper and Guéménée 1982). In 1996, using the collection of Eduard von der Heydt, the museum produced an exhibition on Indonesian ritual daggers (Jav. keris), with a special focus on their elaborate hilts (Kerner 1996). In 2002, some beautiful Wayang Topeng masks from the museum’s collection were prominently displayed as part of the comparative cultural exhibition Masks: Faces from Other Worlds (Langer 2003). In the following years, however, the art of Indonesia remained rather a marginal topic at the Museum Rietberg.

This was to change in 2016 when the museum received a first-class collection of Javanese shadow theatre puppets as a gift from Tina Stohler (Museum Rietberg 2016, 6, 2017, 49–51). The collection, assembled by and belonging to her late husband, Paul, consisted of forty-two extraordinary figures, some of them more than 150 years old. An IT analyst by profession, Paul Stohler (1941–2016) devoted much of his free time to art in the broadest sense and became a passionate collector. He came to know Indonesian shadow puppets through his school friend Walter Angst (1942–2014), a Swiss zoologist who spent several months each year in Indonesia and managed to collect over twenty thousand Wayang Kulit figures (Angst 2007). It is the largest Wayang theatre puppet collection worldwide and was given to the Yale University Art Gallery after Walter Angst passed away. Once the Museum Rietberg had received the Paul Stohler collection, it was clear that this new acquisition would to be presented to the public in an exhibition (Fig. 1). Loans from the Ethnological Museums of Zurich and Burgdorf complemented the show.

Javanese shadow theatre puppets are made of dried, untanned buffalo hide, and have been widely collected for generations as travel souvenirs. They are now present in numerous Western museums and private collections. During the preparation of our exhibition, we realised that Javanese Wayang Kulit has integrated both Hindu and Muslim traditions, and that it has been appropriated by various actors for political, religious, and social purposes. Within this context neither Hinduism nor Islam appeared as clear-cut entities or homogeneous (Hirst and Zavos 2011; Ranganathan 2022). Instead, they were revealed to us as rather vague and fuzzy traditions that are more often associated with ethnic identity.3 Focussing on the interpretations of Wayang Kulit by those involved in this cultural practice, such as artists, craftsmen, and audiences, it was brought to our attention that Javanese shadow theatre should be considered neither Hindu nor Islamic, nor even Hindu-Islamic. These insights were gathered prior to the exhibition during field research in Java by guest curator Eva von Reumont, and then strengthened through the course of our display due to an active exchange with our contacts in Java, Martha Seyowati and her team, who created a series of short film clips with interviews portraying local stakeholders. Our analysis of these interviews shows that according to many contemporary Javanese Muslims, this theatre tradition is not perceived as religious at all, despite its mythological and religious content. This case study invites readers to rethink Western models of interpretation such as Indianisation and Islamisation as they are applied to Javanese history and to challenge essentialist discourses in the public display of Wayang Kulit puppets. Having understood that there is a mismatch between our Western point of view and the self-understanding of Javanese stakeholders, we consciously refrain from applying Western nomenclature to define or determine either the historical-indigenous or contemporary religious sentiments on Java. Before describing our case study, the exhibition, it is necessary to introduce the history and cultural-religious context of the Javanese Wayang Kulit tradition.

Major Cultural Encounters in Java and Their Impact on Wayang Kulit

Java, the most populous island of Indonesia, has a complex cultural, political, and religious history. Indeed, this history goes back thousands of years and is replete with multiple ethnical and religious encounters, interactions, and entanglements. Our focus lies on the diverse imported religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. It is believed that Hindu Shaivism arrived at Java’s courts in the first century CE, finding a “well-established indigenous Javanese social and political culture based on irrigated rice” (Irvine 2005, 3). Archaeological evidence of a Hindu-Buddhist kingdom, located in East Java, dates back to the fifth century, and stone reliefs carved into the Prambanan Temple of Central Java and dating to around 856 show scenes from the Ramayana. The Buddhist monumental stupa of Borobudur was built in the eighth century (Kulke and Rothermund 1998, 203; MacGregor 2012, 447–53). And the largest Hindu-Buddhist4 kingdom, the Majapahit Empire, lasted for just over two centuries, from 1293 to 1517; based in Central Java, it spanned an enormous area from Sumatra to New Guinea. The first Muslim traders may have arrived in Java as early as the eighth century, though it was not until the fourteenth century that the first Muslim kingdom was established there, along the north coast of the island (Ricklefs 2008). These religions arrived from the mainland via maritime trading and commercial exchanges. The autochthonous native traditions they came into contact with were labelled “animistic” by European Christian scholars (Schröter 2021, 137).

The question as to where the particular art form of Wayang Kulit originated may be impossible to answer. So far, no material evidence has been found that pinpoints the beginnings of shadow theatre anywhere else in the world. According to a Chinese legend manifested in the Records of the Grand Historian finished by Sima Qian (†86 B.C.E.), the first Chinese shadow puppet is said to have been created for an emperor in the appearance of his deceased wife (Wang) to help him overcome his sorrow (Psota 1993, 32; Kaminiski and Unterrieder 1988, 18). This legend indicates that the tradition of shadow theatre is expected to be much older than what factual evidence is able to define. Javanese sources reveal that Wayang Kulit was being performed on the island as an integral part of local religious traditions at least as early as the tenth century.5

The Arrival of Hinduism and Buddhism

One of the most influential but also controversial concepts scholars use to understand this early history is the notion of Indianisation, meaning a one-sided export of culture from India towards the East via sea trade and commerce (Schulze 2015, 40–41). For a long time, Southeast Asian culture was explained by Western scholars simply as the result of India’s expansion. The so-called Indianisation of Southeast Asia was even considered to be one of India’s major legacies: Under her impact several kingdoms and temple complexes—Pagan in Burma, Angkor in Cambodia, and Borobodur in Java—came into being. And among her exports were a range of cultural systems, including writing, art, architecture, mythologies, and ritual practices as well as ideas of governance, administration, and divine kingship. As Indian rulers expanded their territories, traders and religious authorities such as Brahmins and Buddhist monks settled throughout Southeast Asia. This major impact seems to testify to the existence of a “Greater India” within the region. However, this theory is open to criticism. Is it not a one-sided perspective? What role did the people of Southeast Asia play in this process? It is perhaps more reasonable to argue that what has been referred to as Indianisation was actually a reciprocal cultural exchange, never a simple one-way movement (Kulke and Rothermund 1998, 195–206).

In fact, Javanese shadow theatre offers an example of how Indian lore underwent some degree of Javanisation upon its arrival on the island. Both Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, became a central part of the Wayang Kulit repertoire: The Ramayana was adapted into Old Javanese during the reign of King Dyah Balitung (898–910), while the Mahabharata was adapted during the reign of King Dharmawangsa Teguh (991–1016).6 These versions, it must be stressed, were not simply copies but differed significantly from their Indian “originals” (Sears 1994).7 The locations, for example, were replaced with Javanese landmarks—the Indian Kingdom of Hastinapura became Ngastina, and Indraprastra became Ngamarta (Sears 1994, 97–98)—while the events reflected local history (Sears 2000, 19), politics, and heroes as well as ancient or recent kings of Java. In the process of appropriation, several of the main protagonists received different names, and some of the spellings were assimilated. Arjuna is also known as Janaka (pronounced Janoko). His elder brother Yudhistira (Skt. Yudhisthira) is primarily referred to as Puntadewa, and Bima (pronounced Bimo, Skt. Bhima) is most often identified as Werkudara or Bratasena depending on which stage he has arrived at in his life (Sudjarwo, Wiyono, and Samurai 2010).

Throughout the centuries of rule by the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms, local Javanese beliefs retained a place in the repertoires of Wayang Kulit. Though the largest repertoire comprises stories taken from the two great Indian epics, ancient myths such as the story of Dewi Sri, the ancestor (goddess) of rice and fertility, can also be found. Whatever name scholars choose to call this complex exchange, the result is a symbiosis and a synthesis of Indian and Indonesian cultures.

Appropriating Hinduism not only enriched and strengthened native beliefs; it also brought political advantages to the reigning kings. The understanding of an ancestral lineage elevated their significance. By integrating Hindu ancestry into their own interpretations of the connection between the past and the present, the kings themselves became representations or incarnations of the famous heroes. To this day, popular presidents of Indonesia identify with esteemed figures such as Arjuna due to their excellent character and virtues. Indeed, identifying with a Wayang Kulit character is very common. A key aspect of Wayang Kulit performances is that by recognising themselves within the characters presented, the audience members are educated in moral conduct (Magnis-Suseno 1981, 136): “From the Wayang characters, their actions and their destinies, the Javanese read the meaning of life” (1981, 137). That is, Wayang Kulit heroes function as role models for human character.

The Arrival of Islam

As noted above, the first Muslim kingdom was established in Java in the fourteenth century. Just two hundred years later, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Muslims conquered the last Hindu-Buddhist kingdom there, the Majapahit Empire. The remaining members of the Hindu kingdoms fled to Bali, where the tradition of Wayang Kulit is practised in a slightly different manner. Although Islam found its way into the Javanese palaces, it did not replace Hindu-Buddhism but rather was added to the existing belief system. The new ideas were absorbed for philosophical and political reasons by the reigning kings, now called sultans.8 Consequently, we argue that the concept of Islamisation, like that of Indianisation, needs to be understood as a complex process of adaptation and exchange rather than a one-way transfer of culture and its automatic, submissive acceptance (Schulze 2015, 43–51).

During the sixteenth century, as the Muslim kingdoms took hold in Java, Wayang Kulit was recognised as a highly elaborated and entertaining medium of communication and therefore as an excellent means to spread the teachings of Islam. Consequently, it flourished (Katz-Harris 2010, 49). A new tradition was created, one that appropriated Sufi philosophical wisdom and ethics and eschewed the depiction of human forms. In turn, the aesthetics of the puppets were altered. While earlier figures likely resembled the human body, as suggested by the stone reliefs on Hindu-Buddhist temples and the Wayang Kulit puppets from Bali, Javanese Wayang Kulit figures became stylised and to some extent abstract (Angst 2007; Brandon 1970; Brinkgreve and Stuart-Fox 2013; Holt 1967; Irvine 2005; Katz-Harris 2010; Platz 1992; Psota 1993; Ulbricht 1970). When they are compared to Balinese figures, the differences are striking (see Fig. 1). According to Susanne Schröter (2021, 139), the continuation of this kind of theatre was justified with the theological argument that the puppets appear behind a screen so the audience does not see real figures but only their shadows—a technique that would not conflict with Islam’s prohibition against figural representations.

The aesthetic changes that took place during this time also enhanced the figures’ symbolic meaning, a point that was emphasised in our exhibition. Features such as the angle of the forehead or the quality and size of the mouth and eyes convey a dense set of information. The different types of noses are categorised by name, as are the different shapes of mouths, eyes, and bodies (Mellema 1954). As will be explained below, these shapes correspond to specific character traits and signal whether a figure is honest, trustworthy, loud-mouthed, deceitful, brave, or timid. In order for the artisans to have enough room to depict all of these meaningful details, the figures’ necks were elongated, opening up the shoulder area and thereby creating unusual proportions. The noses, either pointy or round, are remarkably long, as are the shoulders and arms in comparison to the rest of the body, which looks unnatural. Interestingly, there is also a practical aspect to these over-exaggerated distortions: A pointy nose is easier to differentiate from a round, bulgy one, and longer arms enhance the possibility of fluid movement. As the famous puppeteer Ki Sukasman (1937–2009) explained, the abstract forms also improved the legibility of the characters at a greater distance (Mrázek 2005, 17). Such changes indicate that the artists were—and continue to be—motivated to perfect this performance art tradition.

European Colonial Powers and the Writing of History

European traders reached Java at the beginning of the seventeenth century (Schulze 2015, 53–123), a period which saw the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie; hereafter VOC). The earliest traders showed no interest in the local art and culture, nor did they interfere in local politics. During the eighteenth century, however, disputes and wars of succession within the Muslim kingdoms caused the VOC to begin meddling. They invested financially in the factions that pledged to continue granting them trading privileges (Ricklefs 2018). These investments, as well as fraud within the Dutch leadership, drove the VOC into bankruptcy. By the end of that century, the VOC territories had become Dutch property, and would soon be handed over to the British during the Napoleonic wars.

From 1811 to 1816, the former VOC territories in Java were administered by Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (1781–1826). He was the first European to show a scholarly interest in the island’s cultural heritage and the art forms practised there. Soon he discovered the Indian influence within Javanese culture, and from this point on European scholars began studying Javanese art and culture (Scott-Kemball 1970). Raffles made the revolutionary claim that the world’s civilisations were not limited to Europe and the near East. Java became part of a new narrative that named Southeast Asia as another centre of civilisation (MacGregor 2012). However, he saw Java’s contribution mainly in its Buddhist and Hindu past and not in the Islamic period.

In 1816, Dutch colonial rule was re-established in Java, which brought about many hardships for the people of Java. Due to the Java War (1825–1830) and their conceitedness, Dutch scholars marginalised the Muslim influence on Javanese art forms such as Wayang Kulit. Instead, they propagated the story that the “true” Javanese culture was Hindu-Buddhist (Sears 2000, 47). In both English and Dutch colonial historiography, the Buddhist and Hindu periods were highlighted as the “golden age” of Javanese history. The arrival of Islam was equated with a civilisational backslide—a typical argument in the Orientalist discourse that predominated at the time (Said 1995, 59).

Javanese Wayang Kulit Today

Today, Wayang Kulit is a truly widespread phenomenon, equally popular on the islands of Java, Bali and in parts of Malaysia. In Bali the shadow theatre performances are embedded into ritual practices and sometimes take place during the day, regardless of whether there is an audience (Pink-Wilpert 1976, 65). Wayang Kulit in the classical sense of a traditional shadow theatre performance is now considered part of Indonesia’s intangible cultural heritage and national identity.9 The Indian epics still provide the foundation of the figures’ destinies, though nowadays it is more common to depict episodes from stories, which are created by the puppeteers to fit the purpose of the event and its sponsor. These “branch stories” (Jav. carangan) are new inventions that take place within the backdrop of the base stories and recount the birth, marriage, or transformation of a character. They can be humorous or focus on revelation or mysticism. In recent decades, the performances have elaborated their entertainment aspects, including light shows, artificial mist, contemporary music, etc. and it has become common to live stream performances, either on the puppeteer’s personal YouTube channel or on national television. The stories, as well as their lessons, however, continue to be projected onto current events with the aim of informing audiences about how or why something happened and discussing its meaning.

Our research has revealed that Javanese Wayang Kulit is a repository and source of cultural history, nationalism, ethics, philosophy, and social harmony, rather than the expression of an exclusive religion. Wayang Kulit seems to operate within different religious worlds at the same time but is not identified as a religious practice. And it continues to evolve: In the repertoire of Wayang Pulau, created in the city of Yogyakarta, the stories centre around protecting the diversity of Indonesia’s many cultures. “Unity in Diversity” is one of the five principals of the Indonesian state philosophy known as Pancasila. The protagonists of Wayang Pulau carry the outlines of the largest islands: Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Borneo, and West Papua (pulau means island in Indonesian). The hero and saviour is Geruda, a griffin, Indonesia’s national symbol. By calling on the different religions to help him, Geruda manages to defeat the villain threatening the diversity of the islands. The religions are represented by houses of worship—temples, mosques, churches—which turn into mighty robots during the fighting scenes. The story line, written by Wayang Pulau’s creator, Pak Nanang Rakhmad Hidayat (known by the name of Nanang Geruda), conveys to the audience that cultural and religious diversity is the pride of Indonesia and a sign of strength.10

Since it became possible for Javanese Muslims to travel to Medina and to perform the obligatory pilgrimage, a great deal of Arab money is being invested into Java in order to build beautiful and impressive mosques as well as to finance Muslim universities and other educational institutions. As Middle Eastern Islam gains in importance, the Javanese people may have concerns about whether Wayang Kulit is an acceptable cultural practice. There are a range of opinions. A very small minority wishes to ban performing arts altogether. Those who are aware of its use in spreading Islamic teachings and conformance with Muslim law are certain that Wayang Kulit is perfectly permissible. The Wayang Kulit exhibition held at the Museum Rietberg gave voice to these latter individuals, whose views became the point of departure for our investigation. Their opinions will be presented below.

Practices of Appropriation

In the ongoing process of appropriation and reinvention, Wayang Kulit’s mythological repertoire in Java changed significantly. In its complexity, the different influences are still visible. The pantheon of ancestors in Wayang Kulit, for example, reveals how closely Javanese, Hindu-Buddhist, and Islamic ideas are entwined. In India, Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva are conceived and interpreted as autonomous individual powers whose strengths—creation, persistence, destruction—are complementary. In Wayang Kulit, Wisnu (Skt. Vishnu) appears only as an incarnation of Kresna (Skt. Krishna); Bhatara Brahma (Bhatara being the title of an esteemed ancestor or demi-god) is one of Siwa’s (Skt. Shiva) numerous sons; and Siwa, known primarily as Bhatara Guru, is King of the Heavens—not the highest god per se but the ancestor who practises the strongest form of meditation. Siwa/Bhatara Guru’s figure has no movable arms; motionless, he sits in constant meditation with a ray of energy surrounding him. This position symbolises that he is a manifestation of great virtue. The pantheon reveals many generations preceding Bhatara Guru, all leading back to Nabi Adam as understood from the viewpoint of Islam (Sudjarwo, Wiyono, and Samurai 2010).

Bhatara Guru has two brothers. These characters are of local Indonesian origin and do not occur in the Indian epics. Due to their mischievous behaviour, they were sent down to earth to live as servants to the noblemen and given the names Togog and Semar. Today, as several conversations during von Reumont’s field research in Java revealed, the Javanese interpret Semar as a Muslim invention. By receiving a function on earth, he builds a bridge between the invisible realm (heaven) and mankind, thereby manifesting the concept of egalitarianism. In heaven, Semar was known as Sang Huang Ismaya, who is understood to be the most revered native Javanese ancestor, the father of many heavenly or immortal sons (Moog 2013, 265). Loving, compassionate, helpful and funny, Semar is a highly esteemed figure, though he was condemned to have a most ugly physiognomy in his appearance on earth. He is respected as the wisest figure of all, exceeding even Kresna in wisdom. His role is to counsel the five Pandawa brothers—Yudhistira, Arjuna, Bima, Nakula and Sahadeva—from the Mahabharata and to help them deal with their hardships in a wise and mature manner. It is believed that without his help, the Pandawas would not have won the war. Semar’s Wayang Kulit figure displays his right hand with a pointing finger, which he constantly uses to scold the humans for their many silly failures.

It is crucial to note that the existence of these so-called gods in heaven does not indicate a practice of polytheism.11 None of them are divine beings; rather, they are ancestors who have attained immortality. They each have problems of their own and are constantly confronted with new challenges, which they are unable to solve.12 For example, they depend on Arjuna’s help when heaven is under attack by a powerful ogre.

The “Religious” Aspects of Wayang Kulit

Before we take a closer look at whether Wayang Kulit can or cannot be regarded as an agent of religion in Java, we need to examine how Islam is understood in Indonesia, where the vast majority of the population is Muslim. It is largely accepted that Islam in Southeast Asia differs from the Islam practised in the Middle East or on the Arabian Peninsula. Indonesian Islam, it has been argued, is by its nature tolerant and inclusive. One of the first Western anthropologists to analyse Islamic beliefs and practices in Indonesia was Clifford Geertz. In The Religion of Java, first published in 1960, he singles out three different worldviews, which he refers to as subtypes, subvariants, or subtraditions of the one all-inclusive Javanese worldview or “religion”, as the title of his book implies. This analysis was criticised by Indonesian scholars such as the anthropologist Parsudi Suparlan and the historian Taufik Abdullah (Firdausi 2006). Geertz had in fact focused his research on one particular region, and the details he describes may not apply to Java as a whole. Additionally, since local variations of social structures develop and evolve constantly, the boundaries between the different practices can be seen as fluid. Therefore, Geertz’s statements may not fully correspond to the situation that exists today. Nevertheless, his insights do have some bearing on our argument.

Geertz characterised the first of the three subtypes as a grand syncretism, a “rich mixture of Islamic, Hindu-Buddhist, and native spirits, deities, and culture heroes… Hindu goddesses rub elbows with Islamic prophets and both of these with local [guardian spirits]; and there is little sign that any of them are surprised at the others’ presence” (1976, 40). He refers to this worldview as informal and “barely conceptualised” (1976, 127–30). The next subtype more closely resembles what we mean when we talk about Islam in Indonesia. Geertz writes, “[I]n almost every village and town in Java there was a group, often living in a separate neighbourhood, commonly made up of petty traders and richer peasants to whom Islam was no longer another mystic science among many but a unique, exclusivist, universalist religion, demanding total surrender to a distant God and dedicated to an eternal struggle against the unbeliever” (1976, 126). Geertz distinguishes these first two subtypes in terms of a concern with doctrine as opposed to ritual, absolute truth in contrast to relativism, and an emphasis on the wider community as opposed to the household unit. The third subtype he considers a gentrified variant of the Javanese religion. This variant is concerned with “etiquette, art, and mysticism” (1976, 238). The mysticism concerns the ultimate experience of oneself as a manifestation of God, an experience which is achieved through abstinence and meditation.13 In Javanese Wayang Kulit this phenomenon is described, for example, in a story about Bima, called “Dewa Ruci.” It is very popular and therefore performed regularly. Due to its philosophical nature, it has also received international attention (Arps 2016). Geertz distinguishes the first subtype from the third one as follows: “Mystic practices tend to turn into curing practices; a vague and abstract pantheism gives way to a vivid and concrete [animism]; a concern for individual religious experience is replaced by a concern for group religious reciprocity” (Geertz 1976, 234–35). These thoughts strongly coincide with the worldview represented by Javanese Wayang Kulit, in which characters modelling decent and moral behaviour play a decisive part in every performance.

According to these distinctions, Wayang Kulit in Java belongs more to the gentrified type of Islam. However, just as the boundaries between these diverse Javanese worldviews are fluid, the widespread popularity of Wayang Kulit goes beyond specific groups of people or social strata. Geertz, too, realised this and therefore defined Wayang Kulit as both a classical art and as something that goes beyond a specific audience. It is part of ritualised courtly art as well as of popular culture.

Uncertainty about the religious quality of Javanese Wayang Kulit continues to exist. It is well documented that a shadow theatre master (dhalang) initially functioned as a priest; from this original capacity he continues to follow rituals and ascetic practices such as fasting and making sacrifices, which go beyond a simple theatre performance (Pink-Wilpert 1976, 67–75). In Bali, Wayang Kulit’s ritual nature is far more evident,14 while in Java the relationship between ritual behaviour and performative practice are more ambiguous. Public performances of rituals can be understood by some people as religious acts and by others as theatrical entertainment. It seems that in Java today, attending a Wayang Kulit performance is not automatically perceived as a religious practice. Performances are attended because the audience appreciates the virtuosity, knowledge, and humour of the puppeteer, the beautiful aesthetics, the enchanting music, the philosophy, moral education and entertainment. From our European perspective, it came as a surprise to realise that most of the puppeteers, singers, musicians, and sponsors of Javanese Wayang Kulit as well as most of the individuals in the audience are Muslim and not Hindus. It therefore seems biased to categorise the telling of Indian stories as Hinduism. Using or listening to myths of Hindu origin does not transform people into Hindus.

In the distant past, Wayang Kulit might have been seen as a ritual to protect against evil spirits and as part of ancestor worship. However, this religious aspect has almost been forgotten in contemporary Java (Horsten 1966, 165). Some voices still promote Wayang Kulit as an ideal way to propagate Islam in Java. Ferdi Arifin, for example, states that the values of Javanese Wayang Kulit are “basically in line with Islamic values” (2017, 101). He concludes, “In [the] Wayang play, tolerance, nationalism, and respecting human’s dignity are strongly emphasised in all its characters” (2017, 110). And Indrawan Jatmika explains that not only are the teaching of egalitarian values in Islam identical to the content of Javanese Wayang Kulit, but the faces of the figures were intentionally shaped like Arabic letters (Jatmika 2017, 10). Whether the identification of the puppets facial features with Arabic letters is correct or not, this kind of argumentation reveals how successful and inclusive the appropriation of Wayang Kulit by Javanese scholars, activists, politicians, and artists has been. Its content and values are seen as being in line with Islamic teaching.

Wayang Kulit may be rejected as un-Islamic by some Muslim extremist groups, but in general, it is an uncontested and integral part of Java’s national cultural heritage, which is multi-religious and based on the principles of Pancasila. Wayang Kulit is claimed to be native to Indonesia, and to Java in particular. It is even argued that this theatre existed centuries before Hinduism reached the island. Though a substantial number of the stories are adapted from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, they have undergone many changes. They are undeniably Indonesian.15 Although some Muslim believers seem to question this view, the large majority is not ready to give up this important part of Javanese cultural identity.

Wayang Kulit at the Museum Rietberg

In this section, we offer insights into the process of curating an exhibition on Javanese Wayang Kulit in a European art museum (Figs. 1 and 2).

From 30 May to 29 November 2020, the Museum Rietberg presented Javanese Shadow Theatre: Stories about Life and the World.16 For us as curators it was important to make the figures and the characters, they represent the centre of attention and to treat them as individual agents. In most earlier Wayang Kulit exhibitions, the puppets were sewn onto fabric and presented in a two-dimensional manner (von Reumont 2017, 125–47). We decided to show them in a three-dimensional standing position by inserting their handles into an Ethafoam® base. Several of the most important protagonists were described in terms of their character traits, and the role their attitudes, faults, and virtues played within the stories was explained (Fig. 3). This in-depth approach was new for an exhibition on this theatrical tradition and allowed the underlying ethical message to be discreetly revealed to the visitor. It was also important to demonstrate that Javanese Wayang Kulit, as a form of both moral instruction and skilful entertainment, is still very much alive today. We therefore offered short, contemporary films on the nocturnal world of light and shadow, backstage procedures, and the elaborate production process of the figures. The exhibition layout was enhanced by a beautiful soundtrack of audio sequences from the film footage, which presented the music of the Gamelan orchestra as well as the voices of the puppeteers, singers, and audience (von Reumont 2020).

Addressing Religion in a Western Public Art Museum

Museums that own objects with religious connotations face a challenge: how to deal with their religious significance and identities. Curators must decide, for example, whether to display nakedness or show objects that might hurt or offend some believers. There has even been an interesting and far-reaching discussion as to whether museums may be perceived as “holy shrines” that orchestrate certain degrees of sacredness when displaying these kinds of objects (Beltz 2013, 2019; Bräunlein 2008; Klassen 2017). Among the most difficult tasks is how to explain the multiple significations and meanings that such objects have accrued across time and space. The museum as an institution is widely respected as a source of a truthful, neutral, academically sound, and well-balanced scholarship and expertise.18 As a public art museum, the Museum Rietberg in particular enjoys the trust of its audiences and therefore assumes the responsibility of providing simple and correct answers to complex questions. Curating thus involves translating complex realities into simpler, consumable formats and illustrating contradictory histories through selected and meaningful objects. But how do curators communicate nuances, multifaceted socio-cultural developments, or fluid concepts to an audience that has neither the time nor the interest in reading long and highly academic narratives?

For the Rietberg’s exhibition on Javanese Wayang Kulit, we considered it important to address the following questions: Can this shadow theatre be labelled as Hindu or Muslim? How have the characters, many of which originated from a Hindu source, developed under the influence of Indonesian Islam? How do we describe this art form without imposing incorrect religious contours or promoting fundamentalist identities? We decided to use film as a medium of communication. We therefore produced several videos (published on the museum’s website) to inform our audiences throughout the entire period of the exhibition.19 To start off, we invited Professor Susanne Schröter, director of the Frankfurt Research Centre on Global Islam, to talk about the blending of Hindu and local religious currents with Islam on the island of Java (Museum Rietberg Zürich 2020).

Giving Voice to Contemporary Javanese Stakeholders

We then contacted Martha Setyowati of Surakarta, Central Java, to produce a series of short films.20 Women and men of all ages were to have their say, as well as puppeteers, musicians, and audience members. The series aimed to find out why Wayang Kulit is still so popular in Java today, why it is part of everyday culture, and why it is constantly evolving. The first film focuses on the most important person in a theatre performance: the dhalang, or shadow theatre master (Setyowati 2020a). It showcases Ki Catur Benyek Kuncoro, who is internationally renowned for his creation of a contemporary Wayang Hip Hop repertoire (Varela 2014). In the second film, young Indonesians are interviewed about their personal relationship to Wayang Kulit (Setyowati 2020b). The third film introduces two shadow theatre masters of the younger generation who share their personal views on Wayang Kulit (Setyowati 2020c). The fourth and last film examines the art of creating the hand-crafted and decorated figures (Setyowati 2020d).

Our most significant source of input on the religious questions is the second film, in which young adults from Java speak openly about their thoughts on the relationship between Wayang Kulit and Islam. These interviews demonstrate first-hand that young Muslims consider Wayang Kulit to be an integral part of their cultural and religious identity. Yogi Pradana (age 28, entrepreneur), for example, said that Wayang Kulit is part of Java’s history and therefore of his own history: “If we look back at history, it shows that the Wayang that exists today emerged in the post-Hindu period. So, the form of the puppet figure and the stories developed specifically after the Majapahit Era. That is what the experts say, and I agree with them. We must note that Wayang was modified by the Wali, the Nine Saints who spread Islamic teachings in Java [during the fifteenth century]” (Setyowati 2020b). Yogi Pradana sees no contradiction between Javanese Wayang Kulit and Islam since the teachings of the latter are integrated. Aldhi Wayhu Pratama (age 23, recent college graduate), too, states that “Wayang was used as a medium to spread Islam in Java.” While acknowledging that “in Islamic belief, if you depict a living creature, you basically create a living creature,” he argues that “if we take a look at the puppet, the shape is totally different to human morphology. The bodies are disproportional and mostly have long arms” (Setyowati 2020b). Statements like these are very common. From a Muslim point of view, it is important to declare that the figures used in Javanese Wayang Kulit are artistic creations and do not resemble the human form. They merely refer to humans on a strictly symbolic level.

Following this line of thought, Imam Prakoso (age 28, postgraduate student in linguistics) underscores that “[W]e should keep in mind that Wayang was once used as a medium to spread Islam[ic] teachings.” He further explains: “Islam itself explicitly never teaches Wayang. [In fact,] Wayang is excluded from Islam-based doctrine values. [. . .] So, when some people think that Wayang is considered as idolatry, I guess this is just a misinterpretation. Because we never worship Wayang [figures], or put Wayang and God in the same position” (Setyowati 2020b). These words make perfectly clear that Javanese Wayang Kulit plays no part in idol worship or polytheism, which are great sins in Islam. No one worships the figures, nor does anyone consider them divine. In other words, people who appreciate Wayang Kulit cannot be called sinners because they neither adore nor worship the puppets. Wayang Kulit is human theatre and not service of the divine. Imam Prakoso is not alone in this judgement. Arum Ngesti Palupi (age 29, writer) confirms: “I do not think Wayang is idolatry in Islam. Because Wayang is part of [Indonesia’s] culture. I think it’s unwise if then Wayang [is] associated with someone’s faith. Because faith is [a] personal relationship with God” (Setyowati 2020b). In the same interview, the speaker made the following remark (not captured in the film): “It is unwise to mix these two entities without seeing the historical perspective.” Wayang Kulit is celebrated by these young Indonesians as a form of art and culture, and not as a religious belief or practice.21

Leaving Javanese Wayang Kulit Religiously Unlabled

Javanese Wayang Kulit’s significance clearly surpasses religious boundaries or ritual behaviour. We should perceive this theatre tradition as a performative practice that is not automatically associated with any particular religion. At the core of this art form are its entertainment value and artistic dimensions—the immense knowledge of the dhalang, the delightful voices of the singers, the enchanting sounds of the Gamelan orchestra, and much more—not the religious content.22 Over time, Javanese Wayang Kulit became accepted as a cultural practice with no immediate or exclusive religious connotation. Today it is even a source of social capital: Politicians identify purposely with mythical heroes like Bima (MacGregor 2012, 623). It also provides a platform to criticise politicians, corruption, or bad politics. Even those Javanese who do not care much about Wayang Kulit continue to refer to it as a form of entertainment that is “uniquely meaningful or, as they put it, ‘full’” (Keeler 1987, 14).

It is worth noting that the shadow theatre tradition in Thailand, known as Nang Talung, is also not perceived as something Hindu or Buddhist, or even pre-Buddhist. There, the Ramayana has become the Ramakian, today an essential part of Thailand’s national culture (Noack 2015, 86; Krämer 2015, 128). The same perception applies in other geographic regions. Shadow theatre, as a storytelling tradition, has been performed in cosmopolitan and multi-religious Turkey and Egypt for centuries. As Nina Frankenhauser and Annette Krämer explain, Arabic shadow theatre is appreciated above all as a fantastic form of entertainment. People love to watch stories about villains, sex, and crime that feature jokes, heroic fights, battle scenes, and even critiques of society and politics. Love and spicy eroticism, with even homoerotic or lewd connotations, make these performances so popular (Frankenhauser and Krämer 2015, 21). The fact that this performance art involves human-like figures does not seem to have caused problems in these Muslim societies. This theatre was popular in the Ottoman and Turkish empires and was tolerated in Islamic teaching (Frankenhauser and Krämer 2015; Guenther 2015; Immoos 1979).

With all this in mind, we considered it important to present Javanese Wayang Kulit in our exhibition as neither Hindu nor Muslim in its nature or origin. Javanese Wayang Kulit is above all Javanese, just as Balinese Wayang Kulit is above all Balinese. Our decision to leave the objects religiously unlabelled corresponds to the logic of the Javanese people themselves. After all, the tradition and its symbolic systems reflect the individuals who enact and give life to them.

Exploring religious categories in the context of Javanese Wayang Kulit caused us to reflect on our own perceptions. The labels ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ have traditionally been used in museums to imply conflict or to uphold differences among seemingly clearly distinguishable faith-based communities. However, these are modern preoccupations that may undermine modes of cooperation and even unity. They ignore the fact that both groups might peacefully coexist. It was our ambition to allow visitors to our exhibition to go beyond these categories during their exploration of the manifold dynamics and contexts in which Javanese Wayang Kulit exists.

Conclusion

The Museum Rietberg’s exhibition on Javanese shadow theatre, Wayang Kulit, offered an excellent opportunity to explore the dynamics of the Muslim and Hindu religious traditions on the island of Java in the context of a popular and long-standing art form. We were able to understand how apparently Hindu myths and epics were first transformed into something Javanese, how they then evolved within a Muslim context and how this transition is now perceived by local audiences. This case study revealed that Javanese Wayang Kulit is neither Islamic nor Hindu, nor both at the same time. Its beautifully crafted figures have no inherent religious quality but are used in diverse cultural contexts by diverse agents. The people of Java have interpreted and continually reinterpret this rich tradition and keep it alive. Javanese shadow theatre should therefore be understood through its multiple interactions between individuals and groups across time, regions, and communities.

As curators of the exhibition, we needed to find ways to make these multiple meanings visible to our visitors. We presented the figures as individuals in their own right. Through films and forums (which were presented online rather than in person due to Covid-19), we connected our audience with experienced puppeteers, renowned scholars, passionate collectors, and diplomats from Europe, Indonesia, and India, who helped clarify how Wayang Kulit became such a powerful cultural practice in Java. And we showcased the voices of contemporary Indonesians, who revealed their understanding of what Javanese Wayang Kulit means to today’s audiences. We believe that an exhibition like this strengthens our audience’s ability to make sense of plurality, polyphony, and even democracy (E. von Reumont 2018a, 2018b; von Reumont 2020; Bloembergen and Eickhoff 2020).

Finally, we tried to challenge the dominant narrative, which still sees Southeast Asia as largely the product of its colonial past. Too often the dynamics of Indonesian history remain ignored or unnoticed. With this article, we call for a rethinking of these preconceptions and for new narratives to apply in our Western museums. By questioning concepts such as ‘Indianisation,’ for example, and replacing the India-centric model with one of convergence, we are able to recognise the influences of both foreign and local traditions. A critical evaluation of the notions of appropriation and inclusion will enable a better understanding of how Hinduism, Buddhism, Brahmanism, Islam, Christianity, and indigenous religions co-existed and interacted in Indonesia, a nation that has successfully synthesised these heterogeneous traditions. We envision the Museum Rietberg presenting Southeast Asian art and culture as the result of continuous, multidirectional transfers, enabled by rulers, patrons, priests, students, artists, traders, merchants, shipmasters—in short, a multitude of individuals, social networks, and organisations, many of whom are not credited in the historical record. The temple of art, where antique, precious, beautiful, and often strange things can be viewed and appreciated, obtains an additional mission. It turns into a place where learning occurs through irritation, and questioning established notions, labels and nomenclatures (Bräunlein 2008, 173), allowing us to discover our past but also to reflect on our present.

Acknowledgements

For decades, the history of the Rietberg collection and its institutionalised curation were determined by Western perceptions of Southeast Asia. The present volume is welcomed as an occasion to rethink these categories and to question the logic of the museum’s conceptual framework. In addition to the editors of this volume, Patrick Krüger and Jessie Pons, we thank all partners, collaborators and supporters, who contributed to the success of the exhibition “Javanese Shadow Theatre: Stories about Life and the World.”

References

Angst, Walter. 2007. Wayang Indonesia: The Fantastic World of Indonesian Puppet Theatre. Konstanz: Stadler Verlag.

Arifin, Ferdi. 2017. “Learning Islam from the Performance of Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppets).” HUNAFA: Jurnal Studia Islamika 14 (1): 99–115. https://doi.org/10.24239/jsi.v14i1.457.99-115.

Arps, Bernard. 2016. Tall Tree, Nest of the Wind: The Javanese Shadow-Play Dewa Ruci Performed by Ki Anomo Soeroto. Singapore: NUS Press.

Beltz, Johannes. 2013. “Mysticism: Playing with Religion in an Art Museum.” Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art, and Belief 9 (1): 127–29.

———. 2019. “The ‘Other’ Indian Art or Why Diversity Matters.” Arts of Asia (Sep–Oct), 116–25.

Bloembergen, Marieke, and Martijn Eickhoff. 2020. The Politics of Heritage in Indonesia: A Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brandon, James R. 1970. On Thrones of Gold. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bräunlein, Peter. 2008. “Ausstellungen und Museen.” In Praktische Religionswissenschaft, ein Handbuch für Studium und Beruf, edited by Michael Klöcker and Udo Tworuschka, 162–76. Böhlau: UTB.

Brinkgreve, Francine, and David J. Stuart-Fox, eds. 2013. Living with Indonesian Art: The Frits Lifkes Collection. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum.

Firdausi, Fadrik Aziz. 2006. “Abangan, Santri, Dan Priayi Boleh Jadi Fana, Clifford Geertz Abadi [Abangan, Santri, and Priyayi May Be Mortal, Clifford Geertz Is Immortal].” Tirto.ID, October 30, 2006. https://tirto.id/eknH.

Fontein, Jan. 2007. The Art of Southeast Asia: The Collection of the Museum Rietberg Zürich. Zurich: Museum Rietberg.

Frankenhauser, Nina, and Annette Krämer. 2015. “Das arabische Schattentheater und die ägyptischen Figuren der Sammlung Kahle.” In Die Welt des Schattentheaters von Asien bis Europa, edited by Jasmin Li Sabai Guenther and Inés de Castro, 18–37. Munich / Stuttgart: Hirmer / Linden-Museum.

Gamper, Werner, and Armand de Guéménée. 1982. Materialien zu javanischen Stabpuppen. Catalogue of the exhibition Stabpuppenspiel auf Java. Zurich: Museum Rietberg.

Geertz, Clifford. 1976. The Religion of Java. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Guenther, Jasmin Li Sabai. 2015. “Schatten und Farbe: Das indonesische Wayang.” In Die Welt des Schattentheaters von Asien bis Europa, edited by Jasmin Li Sabai Guenther and Inés de Castro, 100–123. Munich / Stuttgart: Hirmer / Linden-Museum.

Haryanto, S. 1988. Pratiwimba Adiluhung: Sejarah dan Perkembangan Wayang [Pratiwimba Adiluhung: History and development of Wayang]. Jakarta: Djambatan.

Hirst, Jacqueline Suthren, and John Zavos. 2011. Religious Traditions in Modern Asia. London: Routledge.

Holt, Clair. 1967. Art of Indonesia: Continuities and Change. New York: Cornell University.

Horsten, Erich. 1966. “Das Wayang Purva.” In Fernöstliches Theater, edited by H. Kindermann, 121–250. Stuttgart: Alfred Kroener Verlag.

Illner, Eberhard, ed. 2013. Eduard von der Heydt: Kunstsammler, Bankier, Mäzen. Munich: Prestel Verlag.

Immoos, Thomas. 1979. Schattentheater. Zurich: U. Bär Verlag.

Irvine, David. 2005. Leather Gods and Wooden Heroes. Singapore: Times Edition.

Jatmika, Muhammad Indrawan. 2017. “The Role of Wayang in the Spread of Islam in Java.” https://www.academia.edu/37010181/The_Role_of_Wayang_in_The_Spread_of_Islam_in_Java.

Kaminiski, Gerd, and Else Unterrieder. 1988. Der Zauber des bunten Schattens: chinesisches Schattenspiel einst und jetzt. Klagenfurt: Carinthia.

Katz-Harris, Felicia. 2010. Inside the Puppet Box: A Performance Collection of Wayang Kulit at the Museum of International Folk Art. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of International Folk Art in association with University of Washington Press.

Keeler, Ward. 1987. Javanese Shadow Plays, Javanese Selves. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Kerner, Martin. 1996. Keris-Griffe aus dem malayischen Archipel. Zurich: Museum Rietberg.

Klassen, Pamela. 2017. “Narrating Religion Through Museums.” In Narrating Religion, edited by Sarah Iles Johnston, 333–52. New York: Macmillan.

Krämer, Annette. 2015. “Das osmanisch-türkische Schattentheater ‘Karagöz’ und die Sammlung Tugtekin des Linden-Museums.” In Die Welt des Schattentheaters von Asien bis Europa, edited by Jasmin Li Sabai Guenther and Inés de Castro, 124–45. Munich / Stuttgart: Hirmer / Linden-Museum.

Kulke, Hermann, and Dietmar Rothermund. 1998. Geschichte Indiens von der Induskultur bis Heute. Munich: C.H. Beck.

Langer, Axel. 2003. “Leid und Triumph eines Prinzen: Das Maskentheater in Java.” In Masken: Gesichter aus anderen Welten, edited by Albert Lutz, 88–93. Zurich: Museum Rietberg.

MacGregor, Neil. 2012. Eine Geschichte der Welt in 100 Objekten. Munich: C.H. Beck.

Magnis-Suseno, Franz. 1981. Javanische Weisheit und Ethik: Studie zu einer östlichen Moral. Munich: R. Oldenburg.

Mellema, R. L. 1954. Wayang Puppets: Carving, Colouring, and Symbolism. Amsterdam: Tropenmuseum.

Moog, Thomas. 2013. Java. Wayang Kulit. Göttiche Schatten. Salzburg: Mackinger Verlag.

Mrázek, Jan. 2005. Phenomenology of a Puppet Theatre: Contemplations on the Art of Javanese Wayang Kulit. Madrid: Editorial Edinumen.

Museum Rietberg. 2016. Jahresbericht 2016. https://rietberg.ch/medien/downloads.

———. 2017. Jahresbericht 2017. https://rietberg.ch/medien/downloads.

Museum Rietberg Zürich, dir. 2020. Gespräch Mit Prof. Susanne Schroeter Zur Ausstellung “Schattentheater Aus Java”. https://youtu.be/PlZB2y754m4.

Noack, Georg. 2015. “Thailand: Ein Königreich im Zeichen des Ramayana.” In Die Welt des Schattentheaters von Asien bis Europa, edited by Jasmin Li Sabai Günther and Inés Castro, 82–99. Munich / Stuttgart: Hirmer / Linden-Museum.

Pink-Wilpert, Clara B. 1976. Das indonesische Schattentheater. Baden-Baden: Holle Verlag.

Platz, Roland. 1992. Streben nach Harmonie: Kunst und Handwerk Javas. Freiburg i.B.: Museum für Völkerkunde.

Psota, Thomas. 1993. Goldglanz und Schatten: Eine Sammlung ostjavanischer Wayang-Figuren. Bern: Bühlmann.

Ranganathan, Shyam. 2022. “Hinduism, Belief and the Colonial Invention of Religion: A Before and After Comparison.” Religions 13: 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100891.

Reumont, Eva von. 2017. “Applying ‘Western’ Conservation Ethics onto Javanese Wayang Kulit: Survey on Current Strategies, Including International Field Study About Innovations, Boundaries, and Inconsistencies.” Master’s thesis, Bern, Switzerland: Bern University of the Arts.

———. 2018a. “Javanese Wayang Kulit (Shadow Theatre Puppets) Examined from the Viewpoint of ‘Western’ Conservation-Restoration.” Zeitschrift Für Kunsttechnologie Und Konservierung 32 (1): 79–110.

———. 2018b. “Positioning Wayang Kulit ‘Properly’: A Critical Survey on Western Museums’ Conservation Practice.” Master’s thesis, Bern, Switzerland: University of Bern.

Reumont, Maximilian von, dir. 2020. Wayang Kulit Exhibition–Rietberg Museum Zürich. Vimeo video. https://vimeo.com/485178879.

Ricklefs, Merle C. 2008. A History of Modern Indonesia Since 1200. London: Palgrave Macmillian.

———. 2018. Soul Catcher: Java’s Fiery Prince Mangkunagara I, 1726–95. Singapore: NUS Press.

Said, Edward W. 1995. Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient. London: Penguin.

Schröter, Susanne. 2021. Allahs Karawane. Munich: C.H. Beck.

Schulze, Fritz. 2015. Kleine Geschichte Indonesiens. Munich: C.H. Beck.

Scott-Kemball, Juene. 1970. Javanese Shadow Puppets: The Raffles Collection in the British Museum. London: British Museum.

Sears, Laurie J. 1994. “Rethinking Indian Influence in Javanese Shadow Theatre Traditions.” Comparative Drama 28 (1): 90–114.

———. 2000. Shadows of Empire: Colonial Discourse and Javanese Tales. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Setyowati, Martha, dir. 2020a. Meet the Dalang. https://youtu.be/x2Ayy0l_vq0.

———, dir. 2020b. Young Indonesians Talk About Wayang Kulit. https://youtu.be/XcWg8kmzWa0.

———, dir. 2020c. Meet the Young Puppeteers. https://youtu.be/n1kAtB5GLuA.

———, dir. 2020d. The Art Behind the Shadows – the Puppet Makers. https://youtu.be/p88w7GHeFBg.

Sudjarwo, H. S., Undung Wiyono, and Samurai, eds. 2010. Rupa dan Karakter Wayang Purwa [Form and Character of Classical Wayang]. Jakarta: Prenada Media Group.

Thieme, Paul. 1966. “Das indische Theater.” In Fernöstliches Theater, edited by Heinz Kindermann, 21–120. Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner Verlag.

Truschke, Audrey. 2015. Cultures of Encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court. New York: Columbia University Press.

———. 2021. The Language of History: Sanskrit Narratives of Indo-Muslim Rule. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ulbricht, H. 1970. Wayang Purwa: Shadows of the Past. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Varela, Miguel E. 2014. “Wayang Hip Hop: Java’s Oldest Performance Tradition Meets Global Youth Culture.” Asian Theatre Journal 31 (2): 481–504.

This article is based on a talk given by Johannes Beltz at Interreligious Relations in Early Southeast Asia: Encountering Buddhists, Brahmins, and Indigenous Religions, a conference held at the Centre for Religious Studies (CERES) at the University of Bochum, 16–17 January 2020. Eva von Reumont, co-curator of the Museum Rietberg’s 2020 exhibition on Wayang Kulit, joined as co-author although she did not participate in the conference. We would like to thank Jessie Pons and Patrick Krüger for organizing this inspiring and important conference, as well as all those who contributed to and supported it.↩︎

The space was designed in 2007 for the extension building by the museum’s then director, Albert Lutz. However, this logic was not that of its first director, Johannes Itten, who had integrated the ‘high art’ sculpture from Cambodia into the Indian galleries, making it even clearer that this region forms a cultural unity.↩︎

In pre-modern South Asia, the concepts “Hindu” and “Muslim” often signify geographic and ethnic descendance rather than a specific set of beliefs and practices (Truschke 2021, 22).↩︎

The term “Hindu-Buddhist” is frequently used by Dutch and English scholars to indicate that the Hinduism practiced in Indonesia differs from that of India.↩︎

An inscription by King Dyah Balitung from 907 notes that a puppet master named Galigi performed a shadow theatre story called “Bima Ruwat” for Hyang, the Javanese term for the Supreme Being (Haryanto 1988, 26–27).↩︎

This article uses Javanese spelling. For better readability, diacritics have been omitted.↩︎

“The adoption of Sanskritic aesthetics should not, however, be seen as a mere indication of Javanese imitation of Indian models; rather, Javanese literati of that period are shown to have been as sophisticated as their Indian colleagues and able to partake of an esoteric cultural tradition to which only a small percentage of Indic society had access” (Sears 1994, 91). Translating and adopting the Indian myths into Javanese was, in fact, a process of acculturation, which can be compared to the re-creation of the Mahabharata as an Indo-Persian epic by the Mughals (Truschke 2015, 111–21).↩︎

The cultural policies at the Mughal court in India present another striking example of how the Muslim emperors engaged with various Indic arts and cultural traditions (painting, music, literature, and architecture but also food and fashion) to establish, maintain, and expand their power. Audrey Truschke (2015, 246), referring to the role of Sanskrit at the Mughal court, has demonstrated how the exercise of power at the Mughal court was an aesthetic practice.↩︎

Wayang Kulit was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008; see https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/wayang-puppet-theatre-00063, accessed August 1, 2023.↩︎

During her field research in 2019, Eva von Reumont attended a performance of Wayang Pulau at a Muslim Boarding School in Klaten, Central Java.↩︎

The Mughal vizier and poet Abu al-Fazl (1551–1602) argued that Hindus were monotheistic since they believed in one omnipotent God. The existence of multiple Hindu gods did not pose a threat to Islamic theology since they were viewed as intermediaries between humans and Allah (Truschke 2015, 115, 154).↩︎

Bhatara Brama, for example, has several children and a rather problematic story. As a Wayang Kulit figure (see Fig. 3), his face is red, a colour that signals a lack of patience and the inability to control ones’ feelings.↩︎

Both abstinence and meditation are celebrated as great virtues in Wayang Kulit.↩︎

Clara Pink-Wilpert (1976, 65) reports that in Bali, a dhalang has several priest-like responsibilities, for example accompanying a deceased person to the place of cremation.↩︎

Cf. cultural heritage websites such as https://culturalfromindonesia.blogspot.com/2013/07/wayang-kulit-culture.html (accessed August 1, 2023) and https://indonesiacultureheritage.blogspot.com/2012/07/wayang-indonesias-big-treasure.html (accessed August 1, 2023).↩︎

See https://rietberg.ch/ausstellungen/schattentheater-aus-java (accessed August 1, 2023).↩︎

Bima and his son have almost the same physiognomy and are differentiated only by their size and the attributes they wear.↩︎

Today, this perception has been called into question in light of the debate about restitution and the connections between museum collections and European colonialism. As a result, many activists and academics have addressed the role of museums as agents of power and their support of exploitation, racist exclusion, and oppression.↩︎

We had initially planned a series of public talks and performances at the museum, but due to Covid-19 restrictions, all events were conducted digitally. In making the transition, we experimented with new methods. We would like to thank Alain Suter, Lena Zumsteg, Pascal Schlecht, and Elena DelCarlo of the communications department and Masus Meier and Julia Morf of the multimedia team for their efforts and commitment, which made these events possible.↩︎

Martha Setyowati assisted co-curator Eva von Reumont during field research for the exhibition and functioned as a creator, director, and project manager, supervising a creative team that included cameramen, translators, editors, and interviewers. We extend our heartfelt thanks to Ms. Setyowati for her invaluable contributions.↩︎

It would have been very interesting for us as curators to discuss these statements in guided tours or workshops with students or schoolchildren and to ask them to think about why some people consider certain practices as religious while others do not.↩︎

Paul Thieme (1966, 33–34) considered the entertainment Wayang Kulit offers as the reason for its growing popularity all over Asia, from Southeast Asia to China.↩︎