Transforming Faith

Mualaf and Hijrah in Post-Suharto Indonesia

This research delves into two conversion forms in post-Suharto Indonesia: mualaf (conversion to Islam) and hijrah (“migration”, meaning Muslims who reaffirm their faith). Both are integral to contemporary Indonesian Islam, with the hijrah movement’s influence significantly contributing to the increase in the number of mualaf. This study examines the key motives behind urban Indonesians’ conversions, their community involvement, and the formation of spiritual kinship, which is a type fictive kinship. Ethnographic field research and discourse analysis of media reports are employed alongside theoretical debates on community, kinship, and identity. The paper argues that the phenomena of mualaf and hijrah have mutually influenced the growth of new Muslim communities that campaign for a piety movement aimed at a strengthened practice of Islam. Additionally, the involvement of mualaf and hijrah followers in recitation groups implies the formation of spiritual kinship and a unique Islamic identity through the imagination of the ummah and the negotiation of urban lifestyles. This results in the alignment of religiosity and modernity. However, as these groups develop, their emergence, which adds variety to the face of Indonesian Islam, must engage in contestation with other Islamic groups and with the state in terms of religious freedom.

Indonesia, conversion, spiritual kinship, urban Muslims, Islamic identity, hijrah, mualaf

Introduction

Over the past two decades, conversions to Islam, known as mualaf, have witnessed a significant increase, reshaping the dynamics of urban religious life in Indonesia. Such conversions have been particularly notable among adults and public figures, including celebrities, most of whom were previously Christians. The ritual of conversion to Islam, marked by the shahadah—the declaration of faith in one God (Allah) and His messenger (Prophet Muhammad)—has become a common practice among these individuals and is burgeoning into public consumption. This trend of embracing Islam is closely intertwined with the growing Islamic piety movement called hijrah (migration), which means that the Islamic faith is reaffirmed. This is a movement that has gained tremendous popularity among urban communities, especially through its campaigns in social media and its intensive mosque recitations, which influence individuals to convert to Islam.

While both mualaf and hijrah have long histories in Islamic civilization, they share common themes of change, transformation, and devotion to Islam (Bulliet 1979; Casewit 1998; Ernst 2013; Jones 2021). Hijrah is, to borrow some scholars’ definitions of conversion, a conversion within a religious tradition or a form of reaffiliation within the same religious tradition (Rambo 2010, 438; Stark and Finke 2000, 114). Both acts of conversion are conscious decisions to adopt a new way of life based on Islamic principles, involving the abandonment of old habits and beliefs. They also express faith and devotion to Allah, indicating a willingness to make sacrifices for one’s faith. Moreover, both acts of conversion are seen as positive and transformative experiences that bring spiritual growth and renewal to the individual (James 1958; Calhoun and Tedeschi 2001; Gallagher and Newton 2009).

Hijrah, which takes its name from the historical journey of Prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina in the seventh century, has transcended the traditional context of Islam. Today, hijrah for Indonesian Muslims means a commitment to practicing a more Islamic life, emphasizing the importance of repentance, purification, and self-reform, thus making it a kairos-moment in a Muslim’s life phase. This social phenomenon actually occurs in other parts of the world and within religions beyond Islam. For instance, there are “born again” Christians in the USA, the Tablighi Jamaat in Pakistan, the Hindu nationalist movement in India, and the mosque movement in Egypt. The new Muslim communities that have mushroomed in Indonesia since the fall of Suharto’s authoritarian regime in 1998 have been the loudest in echoing the hijrah discourse. New asātīdh (preachers) who were first popular on social media channels and are not affiliated with historic religious organizations in Indonesia are the actors behind the establishment of these religious recitation-based communities. Together with public figures such as celebrities and musicians, they are close to the preaching of Salafism, others to Tablighi Jamaat. But as an Islamic piety movement, hijrah preaching, which reaches out to everyday issues faced by Muslims, has helped individuals practice Islam more rigorously, from performance of worship (prayer, fasting, almsgiving) to changing the way they dress, socialize, choose food, and speak.

The phenomenon of the hijrah movement has captured the attention of Indonesian Muslims, especially through new Muslim communities that have sprung up in many major cities, networking with each other, and revitalizing mosques with recitations. This has had a far-reaching impact, including an increase in the number of individuals converting to Islam. This is because communities of mualaf, such as the Mualaf Center Indonesia, which has been established in almost every city in Indonesia, were initiated and developed by new asātīdh who also fostered hijrah communities. Nonetheless, from a broader perspective, the backgrounds of people who embrace Islam and the process of conversion to Islam are diverse, often lengthy, and highly complex (Ricci 2009, 28).

In Indonesia, the high number of people converting to Islam is influenced by various factors including social, economic and political ones. The country’s large Muslim population of more than 237 million people (86.9 % of the total population) creates a supportive environment for Islam.1 Post-1998 economic growth and modernization have exposed more people to Islamic teachings and ideas, which appeal to their values and aspirations for social justice and equality. Additionally, a rise in religious awareness among Indonesian youth has fostered an interest in Islam and its teachings, seeking spiritual fulfilment and meaning. Lately, the rise of conservatism and political Islam has contributed to the conversion phenomenon, as people see it as a way to express solidarity with the Muslim community and defend their faith in a context of growing religious and cultural tensions.

This article aims to highlight several issues that require further investigation regarding conversion and hijrah in Indonesia. It is particularly important to understand how these mualaf, while participating in the Quranic recitation community to uphold their commitment to Islam, navigate their new religious identity and manage the tensions within themselves, their families, and communities. This includes addressing challenges within the context of modernity, urban lifestyles, and interactions with other Islamic groups. Furthermore, the article explores how spiritual kinship within the community shapes a different Islamic identity. This kind of kinship is grounded in a hadith that states that the Prophet Muhammad likened one believer to another believer as limbs in one body. In this context, the narratives and practices of brotherhood and solidarity among community members serve to strengthen their faith and commitment to Islam.

However, active participation in the community also places mualaf and hijrah followers in contention with other Islamic groups in Indonesia. In previous decades, urban Islam in Indonesia was predominantly influenced by established and historical Islamic organizations, such as Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama.2 Nevertheless, with the emergence of hijrah communities and communities of mualaf, this landscape has undergone significant transformation. On a broader scale, disputes have arisen, and confrontations with the state have occurred due to the Indonesian government’s efforts to control religious groups perceived as ideologically opposed to the country’s foundation, Pancasila (the five pillars).3

Numerous studies exploring conversion dynamics have revealed that transitioning between religious traditions or denominations or embracing religious communities is a multifaceted journey with profound implications across all aspects of life (Rambo 1993; Buckser and Glazier 2003). In contemporary Indonesia, individuals who convert to Islam or undergo hijrah, returning to devout Muslim practices, grapple with the complexities of urban life. Moral decay and individual and social crises often underlie their ethical decision to learn and practice Islam. They deepen their understanding of Islam by immersing themselves in recitation communities that embody the spirit of hijrah, synonymous with devotion. Within these communities, they forge spiritual connections, explore their newfound identities, and affirm their individual and collective Islamic identities. The spiritual kinship in Islam that emerges is largely a result of shared life experiences within the community, significantly impacting social relations (Malik 2017, 199). Through the lens of ummah, which signifies ‘community’ or ‘nation’ and refers to the global Muslim community sharing a common religious identity bound by solidarity, the ideal of a united and inclusive Muslim community is reinforced, particularly by proponents of the piety movement (Roy 2004, 19; Malik 2017, 197). This article, therefore, explores the significance of this kinship formation in the social and religious lives of mualaf and hijrah adepts, examining how it shapes their sense of belonging and identity within the community and how they negotiate these with modern lifestyle.

The investigation of conversion to Islam and hijrah in this study, with its focus on urban areas, points to the distinctive nature of urban communities in many Muslim-majority countries, distinguishing them from Muslim communities in rural areas. As several studies have argued, it is important to understand the nature of urban Muslim communities and the forces that shape them, including political forces, the evolution of urbanization, and linkages with wider society, in order to comprehend their development and significance (Lapidus 1973; Kahera 2002; Hatziprokopiou and Evergeti 2014). Additionally, the development of digital technology, which impacts urban communities more intensely, has been effectively utilized by Indonesia’s new Muslim groups, including hijrah groups and mualaf communities, in proselytizing Islam on social media. For Indonesian Muslims, the topic of conversion to Islam has become increasingly important, considered positive news and receiving significant attention in infotainment programs (Budiawan 2020, 189). On social media, for example, religious conversions are easily found, heard, and discussed. In various events organized by the hijrah community, sharing sessions on the experiences of mualaf are always a part that garners the enthusiasm of many people. Thus, the conversion experience has become an interesting and inspiring piece of entertainment (Hew 2018, 61; Jones 2021, 178). In terms of social media, considering that Indonesia is one of the countries with the largest number of social media users in the world, hijrah groups are well aware of how this new media plays a strategic role in the arena of discursive battles among Islamic groups, although in terms of daʿwah (preaching Islam), it has been mixed with various social dimensions such as consumerism and the practice of buying and selling Islamic goods and services, or what Daromir Rudnyckyj calls “Market Islam” (Rudnyckyj 2009; see also Gauthier 2020, 233–51).

Through ethnographic study and discourse analysis of media reports on mualaf and hijrah communities, specifically examining Mualaf Center in Jakarta, Pemuda Hijrah (Hijrah Youth) in Bandung, and Muslim United in Yogyakarta alongside exploring theoretical debates surrounding community, spiritual kinship, and identity, this article addresses the above points by starting a discussion of the historical context of conversion to Islam and the hijrah movement, especially in the Indonesian context.

A total of 15 in-depth interviews were conducted between 2020 and 2022 with individuals who have converted to Islam from Protestant and Catholic backgrounds and with those actively involved in the hijrah movement in the three cities. The respondents were selected to ensure diversity in terms of age, gender, and socio-economic background, with an even distribution across the three locations. This diverse sample allowed for a thorough exploration of the complex phenomenon of faith transformation within these communities. Interviews were conducted in a semi-structured manner, with open-ended questions that encouraged participants to share their personal stories, experiences, and beliefs, aiming to shed light on different aspects of their faith journey.

The introduction is followed by an analysis of the emergence of new Muslim groups in urban Indonesia since the fall of the Suharto regime. The third section analyzes the main motives behind conversion to Islam and the decision to adhere to hijrah for Muslims, as well as their individual narratives and experiences. An exploration of the integration of mualaf and hijrah participants into networked communities of both hijrah and mualaf follows in the fourth section, which also addresses the concept of spritual kinship and how it is constructed within these communities. Section five examines the negotiation of urban lifestyles and modernity, before a section analyzes the formation of a unique Islamic identity and discusses the contestation and interaction of mualaf and hijrah participants with other Islamic groups and the state. Finally, the conclusion reflects the broader implications of this research for understanding religious conversion and contemporary Islam in Indonesia.

Socio-Political Context of Conversion and Present-Day Dynamics

Historically, religious conversions in Indonesia have often been intertwined with sociopolitical factors (Ricklefs 2001, 3–15). One such historical moment was the massacre of millions of people accused of being communists and/or affiliated with the Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia/PKI) during 1965–1966, which is still vivid in the collective memory of Indonesians today (Anderson 2001; Santoso and Klinken 2017). Most of the early trauma of Suharto’s New Order regime,4 which weighed heavily on Indonesian society, was channeled into a wave of religious conversions. Six years after the genocide, approximately 2.8 million people, constituting 2.77 % of the population at the time, had converted, mostly to Protestant and Catholicism. These conversions occurred mainly in the provinces of East Java, Timor Leste (formerly East Timor), and North Sumatra (Cribb 1990, 40). Around one-sixth of the conversions occurred to Hinduism. However, unlike the Christian converts, a significant number of Hindus returned to Islam within the subsequent years (Hefner 2003, 94).

In this historical context, there were numerous motives for conversion. Since Suharto assumed national power in 1966, the New Order state mandated all Indonesians to acknowledge the existence of God and adopt one of the state-recognized religions (Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Balinese Hinduism, Buddhism, and Khonghucu), lest they be branded atheists (Lindsey and Pausacker 2016, 30). Atheism was equated with accusations of communism. Consequently, conversion had to be formalized through official registration. Moreover, since 1965, Christian churches in Indonesia have been under suspicion for their perceived ties to the West, although this perception can be explained as communist propaganda. Nonetheless, the significant number of conversions from Islam to Christianity indicates that the political upheaval of 1965 deeply affected many individuals, causing them to lose faith in their previous beliefs. In consequence, they embraced a new religion despite its negative connotations. Christianity represented a fresh start for many and was either warmly embraced within these circles or appreciated for the welfare activities conducted by Christian groups. Additionally, the fear of persecution during the anti-communist purges incentivized some to convert to Christianity as a means of protection (Nugroho 2008, 122).

According to Avery T. Willis (1978), an American missionary working in Indonesia since 1964 and head of the Indonesian Baptist Theological Seminary, there were various factors leading to the mass conversion to Christianity/Catholicism during this period of Indonesia’s history. The most crucial of these factors were related to political turmoil, especially to the communist party (PKI). They included the psychologically oppressed position of PKI followers due to the agitation of political opponents, which was then successfully exploited by Christian and Catholic clergy. The overreaction of some Islamic leaders at the time to Muslims who were members and sympathizers of the PKI also encouraged people to look elsewhere for spiritual help and political protection. At the same time, the church’s protection of people accused of being PKI members and those who were not truly religious from being killed and losing their social status improved Christianity’s image in Indonesia. In addition to the care and services of church institutions, including education, medical assistance, and other basic needs further enhanced attraction to Christianity, to the extent that the church was able to provide help for conversion to Christianity (1978, 25).

This dark period in Indonesia’s history shows the link between conversions and the sociopolitical situation. Although the PKI suffered a defeat in the 1965 uprising, Indonesian Muslims also experienced silencing. This was particularly evident during the period following the euphoria of welcoming the New Order regime, which replaced the PKI and communism. Critical voices from Muslims to the New Order regime were suppressed. Subsequently, there was a shift of Islamic political aspirations in Indonesia that persisted until the 1980s.

Muslims euphorically welcomed the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998 and flooded public spaces with Islamic narratives. Unfortunately, this period was followed by the 2001 terror attacks on the New York World Trade Center and the 2002 Bali bombings that shook the Islamic world. The face of Indonesian Islam was no less badly perceived internationally. Since the early 2000s, the seeds of transnational Islamic networks began to sprout, also in Indonesia. Moreover, the global political turmoil among various factions within Islam also spread to Indonesia. In contrast to François Gauthier’s assertion that the post-Suharto Islamic revival was moving away from political Islamism (2020, 238), the political struggle of Islam, which has a long history dating back to the independence struggle, found its feet with democratization and openness to various religious expressions, including radical understandings of Islam, commonly referred to as Islamism or political Islam (Sirry 2008, 466; Arifianto 2020). Therefore, one of the conspicuous hallmarks of post-Suharto Indonesian Islam is the emergence of a pliable political Islam, which has led to tensions between the state and some elements of Islamic civil society.

Moreover, the contestation between Islamic and other religious groups has also come to the fore. In this regard, Indonesian society currently searches for a new optimal relationship between the state and religion. As a recent example, the rise of religious conservatism has prompted the state to take part in preventing the growth of Muslim communities that embrace ideologies that contradict Pancasila (see note 2). The principles of democracy have been ignored for this purpose, such as the dissolution of Hizb ut Tahrir in Indonesia (HTI) and Front Pembela Islam (the Islamic Defenders Front/ FPI). State interventions to this intent have fueled the anger and disillusionment of the Muslim community. Some state policies, on the other hand, have been appreciated by religious communities in Indonesia. One of them is accommodating the recognition of the ancestral religions of the Indonesian people. Religious communities such as Kejawan in Java, Sunda Wiwitan in West Java, Balinese Hinduism, and Kaharingan in the Dayak community in Kalimantan became recognized religions in 2019 and could be included on the identity card. Consequently, some Muslims and Christians (re)converted to their ancestral religions with full conviction.

This short survey emphasizes that conversion from one religion to another, and vice versa, has become commonplace in Indonesia due to particular state policies. Almost the same thing happened at the emergence of the hijrah movement, which in its development became one of the triggers for the increasing number of people converting to Islam It, too, has a background of local upheaval and subsequent democratization in Indonesia.

The hijrah groups observed in this research, for example, emerged in the 2014 presidential election, the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial race, and the 2019 presidential election, where Islamic identity politics divided society in such a way that its residue was still felt years later (Mietzner 2020; Mujani 2020). The movement’s leaders and followers, along with Islamist groups such as FPI and HTI, supported Prabowo Subianto in the 2014 presidential election as a rival to Joko Widodo, who was perceived as “anti Islam.” Then, in the 2018 Jakarta gubernatorial election, support was directed to Anies Baswedan, a Muslim of Arab descent, because his opponent, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a Chinese Christian, was still difficult for most Indonesians to accept as governor. This was exacerbated by the fact that he was eventually caught in a blasphemy trap that triggered the largest Muslim protests in history.

Around 2013, the hijrah movement gained prominence as new translocal Islamic communities emerged in major Indonesian cities, promoting hijrah in public spaces and on social media with a distinct style of Islamic daʿwah. The precondition for participating in this movement was tawbah (repentance), denoting the changed attitude to Islamic teaching when a Muslim has lived a life that is far from Islamic values, including drug use, the glamorous entertainment world, or urban lifestyles that are considered sinful. The development of transnational Islamic networks, such as Salafism and the Tablighi Jamaat in Indonesia is one of the reasons why many people choose to commit to hijrah, enabling it to become a movement. Therefore, albeit relatively new, the movement has non-linear historical roots and is not merely a localized dynamic.

The hijrah movement, as demonstrated by the Pemuda Hijrah group in Bandung, targets urban Muslim youth who are considered fragile in their understanding of Islam because of their lifestyles. The group’s activists have recognized this niche, which has received less attention from other Islamic groups. Hence, it becomes an opportunity for them to accommodate the religious needs of the urban community through various religious activities, especially recitation. The spread of this movement is also possible because of social media technology. Through platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and lately TikTok, asātīdh and activists of the hijrah movement have gained popularity. Their followers continuously increase, reaching tens of millions. Using Islamic content on social media, many urban Muslims not only decide to employ tawba and engage in hijrah personally but also actively attend regular recitations at mosques and become members of the hijrah community.

The hijrah community has become a sanctuary for many Indonesian Muslims facing various social and economic challenges in urban life. The desire to rediscover the meaning of life drives individuals from all social classes to embrace hijrah. For example, some who worked in banks, which some Muslims believe involve illegitimate transactions such as riba (usury), decided to leave their jobs and dedicate themselves to the path of hijrah to preach Islam alongside more traditional asātīdh. Similarly, there are those who left their positions in large companies after discovering that their workplaces follow what they perceive as un-Islamic trends, such as support of the LGBTQ-movement, choosing instead to join the hijrah community.

The ethical decision to perform hijrah and engage in Islamic preaching through hijrah groups has strengthened these individuals. Together with other followers, they look forward to a more Islamic future. Although the main motives of hijrah followers are self-reform and self-purification, there are underlying economic and political motives within the movement’s daʿwah strategy. Activists of the hijrah movement in major Indonesian cities often have resources and backgrounds as businessmen, celebrities, or other public figures.

In Bandung, West Java, for instance, movement activists not only provide opportunities for young people in street communities to attend Quran recitations but also capitalize on the market potential of hijrah followers by marketing Islamic goods and services. Notably, after the 1998 economic crisis, the growth of the Muslim middle class in Indonesia surged, which led to a massive trade in Islamic goods and services. Among the most prominent activists are members of the hijrah community in Jakarta called Musawarah, initiated by well-known Indonesian celebrities. These hijrah activists are also major suppliers of Muslim clothing and food, producers of Islamic films, and owners of Hajj and Umrah services, including tours to Islamic sites in places like Egypt and Turkey (Fansuri 2023).

Through hijrah communities based on routine recitation in mosques, the movement has attracted sympathy from urban communities, including those of other faiths. The movement has introduced a daʿwah strategy with a cultural approach that questions everyday language and reflects on everyday complicated life while offering Islam as the best way out. It has profoundly impacted individuals seeking to fulfill spiritual needs and refuge from life’s intricate challenges. Quite a few Indonesians have decided to embrace Islam or repent and commit to hijrah because of this Islamic proselytization strategy. Moreover, this movement is also known for the involvement of public figures, including celebrities, who convert to Islam or commit to hijrah and later become asātīdh in the hijrah community.

The emergence of new asātīdh from among celebrities, musicians, and mualaf within the hijrah movement has sparked debates around traditional religious authority in Indonesian Islam. This authority is deeply rooted in Indonesian society, exemplified by the role of the Kiyai, a local term for a cleric who has received Islamic education at a pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) or madrasa and can demonstrate a clear clerical genealogy (Saat and Burhani 2020). Additionally, the rise of hijrah groups in many cities has led to contestation with mainstream Islamic organizations such as Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama, which have shaped the face of Indonesian Islam for over a century. This contestation has, in some cases, caused friction among Muslims, with recitations featuring hijrah asātīdh being banned, canceled, threatened, and accused of spreading hatred.

Since hijrah groups emerge and network mainly in cities, they intersect with Muhammadiyah followers, whose distribution patterns have always tended to be urban. Many hijrah movement followers come from Muhammadiyah backgrounds, especially through their families. This distinguishes them from Nahdlatul Ulama, which has its roots in pesantren and rural areas. Although in contemporary developments, the dividing line between these two patterns has faded. The responses of the two organizations, which have more than a hundred million followers, are very different. Among Muhammadiyah followers, the hijrah movement is not seen as a significant threat. In contrast, some officials and activists of Nahdlatul Ulama view the hijrah movement as promoting Islamic understandings that are incompatible with the cultural nuances of Indonesian society. This has led to cultural codes, such as calling the hijrah movement Wahhabism or claiming that it threatens Pancasila.

Conversion Motives and Experiences

The general trend of people embracing Islam and committing to hijrah, as mentioned above, is motivated by a search for religious and spiritual sanctuary from the life problems they face. However, each individual has diverse additional motivations. In the case of mualaf, some of the main motives relate to the search for meaning and purpose in life. For them, Islam offers a sense of both. In other words, mualaf perceive Islam as providing answers to the most fundamental questions of existence and offering practices for living a morally and intellectually good life.

The complexities of Indonesian urban life and its uncertainties are another reason for people to become aware of the lack of spiritual fulfilment in their lives and become Muslim, i.e., become devoutly religious persons who consider themselves useful. This is because they interpret the conversion to Islam as creating a divine connection and deepening their spiritual practice, which in turn moves them to identify as more meaningful human beings.

For some mualaf, the engagement in the Islamic communities offers a sense of togetherness and community backing that they do not get elsewhere. They perceive the Muslim communities as providing a supportive and welcoming atmosphere, where they are valued, accepted and even encouraged to be pious. In this regard, embracing Islam becomes a transformative experience (see Wohlrab-Sahr 2006; Burhani 2020). They view this spiritual journey as a life path to leave behind old ways of thinking and habits and embark on a new chapter in their lives. In certain cases, some mualaf also see Islam as a platform for political or social activism, which thus serves as a way for them to seek social justice, including campaigning for changes both in the Islamic communities and in the wider society.

Such is the case with many of those who commit to hijrah, as mentioned by my interlocutors. They became aware of the way their previous life has deviated from Islamic values and they felt an emptiness in their lives. In some cases, they experienced great losses, such as divorce, breakups, or business failures. The hijrah experience is, for some Muslims, associated with the urge to join or involve themselves in a community. For them, it becomes a kind of social necessity to not only find colleagues but more importantly to find spiritual warmth in Islam and a place to discuss various problems they are facing. When they find themselves living a life that they consider far from Islamic values, or when they face the emptiness of life amid a prosperous and well-established appearance, they feel the urge to seek answers to all of that through the recitation communities.

These communities are indeed becoming one of the references of many Indonesian urban Muslims today, due to their reach and intensity in preaching Islam through digital spaces, in addition to reviving mosques with religious recitations, and organizing fee-based recitations. Indrawati, for example, one of the interlocutors I met in Jakarta, shared her spiritual experience in several conversations, especially about committing to hijrah while joining the mualaf community. As a middle-class Muslim woman, she experienced severe life pressure when her romantic relationship with a Christian man had to come to an end. Apart from not being approved by both parents, it was also due to the man’s unwillingness to embrace Islam. However, in that devastating phase, she received a wake-up call to return to God.

I was at a very devastating phase in my life and finally sought strength by returning to Allah. Slowly learning again, pouring out my heart to Allah little by little, increasingly depending on Allah, and replacing the role of the ex-boyfriend with Allah. I also learning to believe that all prohibitions and commands are for good. (Interview with Indrawati, 4. September, 2021)

The urge to return to Islam and God, according to her, was triggered by past religious experiences as well as by appealing Islamic daʿwah content on the Internet and social media that often touches on daily life experiences. Indrawati also believed that almost every Indonesian Muslim has such past experiences because, since childhood, they have been exposed to all sorts of Islamic activities, such as recitations and various Islamic festivals. These two things, she realized, kept her from sinking into prolonged sadness and emptiness. In this case, the psychological dimension, especially the response to deep personal experience, suggests that “religious experience” led her to be able to adopt a new self as a Muslim.

She found hijrah communities through Internet searches and social media. In the holy month of Ramadan, she decided to leave her home, parents, and job to live for more than two weeks in a pesantren in the southern part of Jakarta, the An Nabba Center. This Islamic boarding school that is specialized on catering to mualaf is in some places closely connected to the hijrah communities, which are run mostly by the same people. At the pesantren, she learned various things about Islam under the guidance of several asātīdh. From this experience, she gained the strong conviction that, in fact, everyone has a relationship with God. Therefore, she still hoped that her ex-boyfriend “would experience divine guidance and embrace Islam,” even though her romantic relationship with him had come to an end. This case reflects two things at once, namely hijrah and religious sanctuaries. Hijrah means returning to the path of Islam, emphasizing the commitment to explore Islam, while religious sanctuaries, such as the mualaf boarding school and the hijrah communities offer paths for Muslims at a crossroads or in the midst of a personal or social crisis.

In terms of converts to Islam among prominent Indonesian celebrities and musicians, their spiritual experiences inspire many Indonesians. This inspiration is partly due to the attractive presentation of their stories in podcasts and on social media channels. While a common trend among celebrity mualaf is marrying a Muslim spouse, many other conversion stories arise from abstract and mystical experiences. These include dream experiences or being deeply moved by hearing recordings of Quranic recitations, such as adhān (the call to prayer). Some conversions result from deep contemplation and a search for religious truth. With its wide reach, social media is not only effective in introducing these faith transformation experiences but also collaborates with hijrah groups to amplify the piety movement’s impact on society. For example, at every Hijrah Festival—an annual event where hijrah groups meet in a bazaar of Islamic goods and services—there is always an enthusiastic sharing session for mualaf. At the 2018 Hijrah Festival in Jakarta, a foreigner, Brian Jones from Georgia (USA), declared the shahada on the festival’s main stage, guided by a preacher. A total of 18 people converted to Islam during the three-day festival. Some of them later became involved in mualaf communities that often collaborate with hijrah groups at the Hijrah Festival. The shahada pronouncements and mualaf sharing sessions have become part of the festival’s agenda for promoting hijrah, with the event consistently attracting more than five thousand attendees each day since it was first organized in 2017.

Therefore, the increase in the number of mualaf over the last two decades has coincided with the hijrah movement. The movement has become an attraction for mualaf seeking guidance in their initial phase of embracing Islam. One of the most influential communities for mualaf in Indonesia, Mualaf Center Indonesia (MCI), was founded by Steven Indra Wibowo (1981–2022) who was also a hijrah and daʿwah activist. In a February 2019 interview in Indonesia’s leading newspaper, Republika, he mentioned that more than 50,000 people had converted to Islam through his community since 2003. According to him, up to 3,500 mualaf per year were recorded across Indonesia, with the predominant reasons being Muslim partners and marriage. However, he also noted that the hijrah trend, where young urbanites commit to hijrah, has become a significant factor in the increasing number of mualaf in Indonesia.

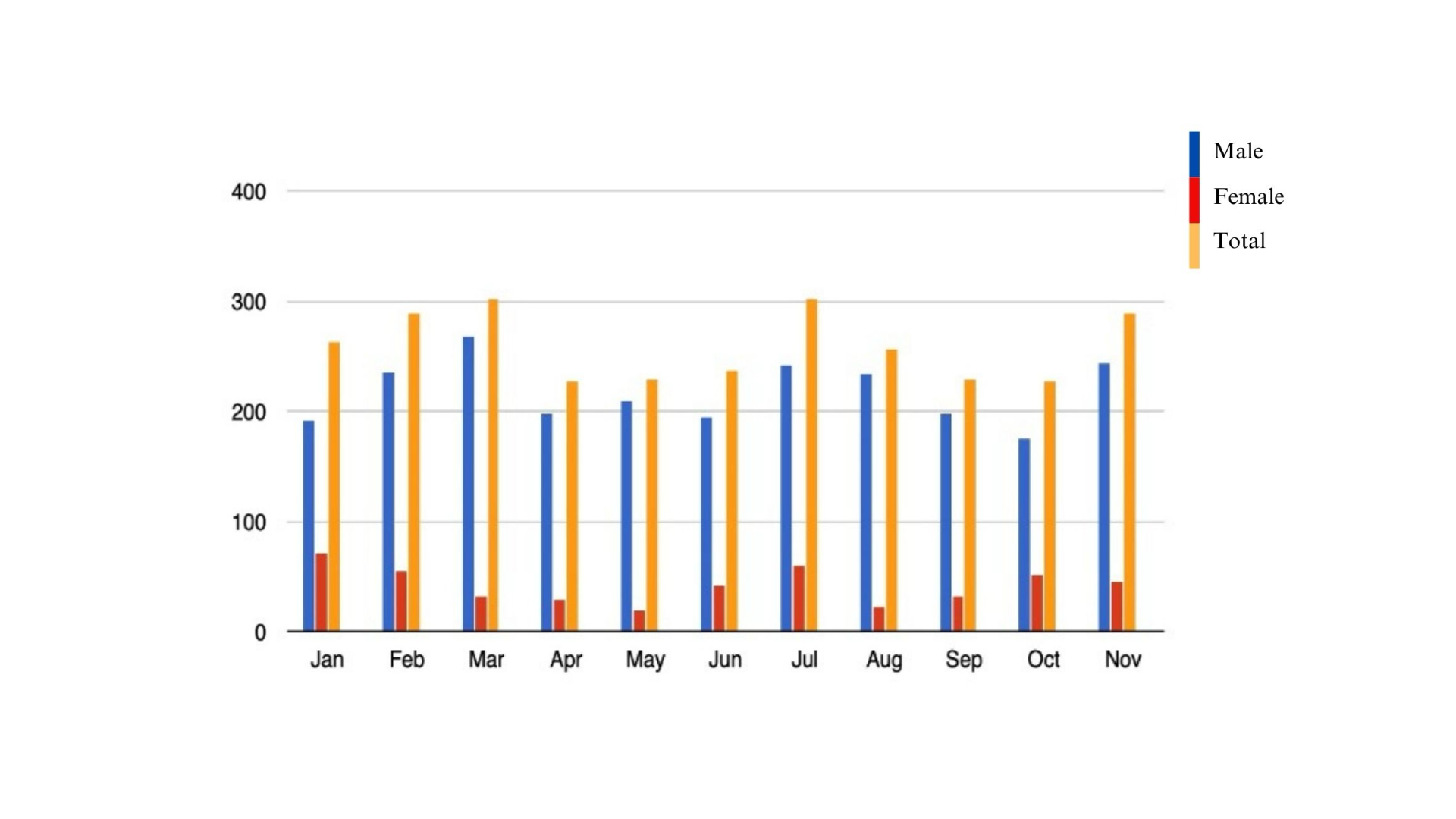

Figure (see fig. 1), based on 2017 data from MCI, illustrates various aspects of people converting to Islam in Indonesia, especially in terms of gender. Conversions among men are much more common than among women. However, female mualaf tend to be more active in community activities than their male counterparts. Women seem to be more fully committed to learning and becoming pious Muslims than men.

Community Engagement and Spiritual Kinship

One of the themes in the hijrah movement campaign is emphasizing the significance of community involvement over solitary commitment to hijrah. This emphasis is rooted in the belief that within the community, one can find like-minded individuals who share the same motivation for change, with knowledgeable asātīdh serving as mentors. Since hijrah is a challenging journey that demands istiqāmah (unwavering perseverance), active participation in the community is considered crucial. In this community, both mualaf and those who have undertaken hijrah discover not only their transformed selves but also engage in various community activities that promote the spread of Islam. Being a daʿwah activist is their common guideline, as it is believed to nurture faith and good deeds, in addition to achieving the essence of prayer, which is to prevent abominable and forbidden deeds. In this context, religious contacts and the practice of Islamic values closely tied to the community to which individuals belong assume paramount importance in the lives of those committed to reaffirming and fortifying their faith in Islam. The relationships and interactions they foster not only offer opportunities for worship but also nurture a sense of unity and brotherhood among Muslims. It also entails seeking guidance and knowledge from asātīdh and religious mentors to help assist individuals negotiate life’s challenges while staying true to their Islamic faith. Ultimately, these relationships within the Islamic community play a central role in the ongoing process of renewing faith and achieving spiritual growth.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that a considerable number of individuals are inspired to join the hijrah community due to the influence of celebrities, musicians, and influencers who have either embraced Islam or undergone hijrah themselves. In the era of social media, which holds considerable sway among urban Indonesians, the experiences and spiritual journeys of these public figures resonate with their followers, motivating them to support the hijrah movement, contemplate their religious practices, and actively participate in the community. In collaboration with pop preachers, these public figures effectively serve as “Muslim Televangelists.” They not only utilize and trade in Islamic symbolic and economic capital and media technology but also share their conversion narratives and contribute to the establishment of religious authority (Howell 2001, 232; 2008, 48; Hoesterey 2012). Moreover, these celebrity mualaf and hijrah participants, with their prominently displayed piety, captivate their followers by merging image and influence to cultivate an audience and inspire enthusiasm for piety (Jones 2021). Among the celebrities are Larissa Chou, Tere, Dewi Sandra, Stevi Agnecya, and Roger Danuarta. They are often involved in the hijrah da’wah movement, including sharing the story of their spiritual journeys on social media channels and at the Hijrah Festival. The collaboration between public figures, asātīdh, and other Middle Eastern graduates solidifies the continuous growth of the piety movement community’s followers.

Integration into the community, thus, typically begins by following the social media accounts of these public figures and popular asātīdh, driven by the desire to emulate those perceived as devout Muslims who epitomize a high level of faith in Islam. The Islamic content they follow not only raises their awareness of an appealing interpretation of Islam that aligns with contemporary trends but also serves as a source of inspiration, illustrating that the piety movement within the community can alleviate the burdens of their daily life, including the sense of emptiness amidst material sufficiency. Furthermore, social media content often piques their curiosity about the location of the hijrah community and the mosques where regular recitations take place. Generally, newcomers to the community receive a warm welcome when they actively participate in various activities and recognize their importance and utility within the community. Some of my interlocutors in the hijrah communities in Bandung and Yogyakarta emphasized how the sincerity of their involvement in the community is demonstrated through their willingness to contribute with community activities, their sense of belonging, and their active engagement in efforts to strengthen the community.

Based on information gathered from my interlocutors in various hijrah communities across Indonesia, it is evident that there are specific stages individuals must go through before they can be fully integrated into the community. This process, as attested by those who have become activists within the community, must be undertaken sincerely, irrespective of one’s previous background. Initially, individuals typically attend regular recitations. If there is a volunteer recruitment process, they may have the opportunity to become involved in organizing events for various community activities or directly assisting the community in various tasks, following the directives of their supervisors. For example, a leader responsible for regeneration within the Pemuda Hijrah community in Bandung, West Java, shared his experience of initially joining the community as a technician, providing assistance during recitations. Recitations organized by hijrah communities usually follow a consistent pattern, utilizing various live-streaming platforms such as YouTube and Instagram channels, necessitating the involvement of numerous individuals for this purpose. The determination of each individual’s position, and the appointment of who is the head of each division, is decided by the community’s founder and the asātīdh. It is in this role that individuals begin to work professionally and receive compensation, often referred to as a scholarship, as they function as students learning from the asātīdh. This gradual process of involvement is also observed in other hijrah communities I have encountered, such as Muslim United in Yogyakarta and Munzalan, based in Pontianak, West Kalimantan.

Within the hijrah communities, spiritual kinship flourished. I use this term as a way of seeing and understanding the larger universal religious solidarity of the ummah, as envisioned in sacred texts and religious discourses, forged among Muslims. Historically, studies of spiritual kinship have focused on the ritual of baptism in Christianity and the subsequent creation of bonds of spiritual kinship through relationships as godparents (Alfani 2017). This kinship primarily arises from building connections and relationships among community members, asātīdh, activists, and followers (including mualaf), and through congregational Islamic worship practices, as well as discursive practices of hijrah and Islamic ethics in various social domains and networks. In essence, spiritual kinship entails individuals forming close and meaningful bonds based on shared religious beliefs, practices, or experiences of embracing Islam, in the case of mualaf, and repenting, in the case of hijrah. Such kinship is frequently characterized by shared values, mutual support, loyalty, and a profound sense of belonging (Ebaugh and Curry 2000; Tierney and Venegas 2006; Osman 2010; Schwartz 2012; Malik 2017; Alfani 2017). In this context, spiritual kinship assumes a pivotal role in providing emotional and social support, nurturing a sense of community, and reinforcing one’s spiritual and religious identity.

It is intriguing to observe that hijrah communities revolve significantly around charismatic asātīdh who inspire followers and activists of the hijrah movement to demonstrate loyalty and obedience. Such charismatic asātīdh have played a pivotal role in the emergence of the hijrah movement. Beyond their religious authority in Islam, these asātīdh are also considered as capable of guiding their followers towards a better future. Asātīdh from various backgrounds, including Azharites (those who graduated from Al Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt), graduates of other Middle Eastern universities, celebrities, and even some mualaf without formal religious education, are held in high esteem. Their role has become so vital that the bond between them and their followers in the community is as strong as familial ties, whether through blood or marriage. Followers are willing to offer support and defend their asātīdh when they face challenges. At times, community members also place their trust in the asātīdh for sacred matters, especially in the search for a suitable spouse. Therefore, their role as asātīdh, educators, and helpers is often regarded as an extension of parental guidance.

Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that individuals within the hijrah community can establish various levels of relationships with each other, including social ones, such as friends, colleagues, and neighbors. In them, kinship, as Ladislav Holy pointed out, is the idiom through which religious values are expressed by performing religious rituals together (Holy 1996, 137). In certain instances, the kinship within the hijrah communities, including in pesantren for mualaf and other Islamic groups, can be even closer than biological kinship, especially when they put their trust in the azatis, share the same spiritual experiences (Osman 2010, 167–69; Malik 2017, 208), and, in the case of hijrah, draw a clear line between those who commit to hijrah and those who do not, or between mualaf and non-Muslims. However, not all followers of the hijrah movement can maintain unwavering loyalty to a specific community or asātīdh. Their rationality causes some of them to prefer communities and asātīdh that are perceived to be in line with their urban lifestyle needs. This demonstrates that they are active receivers who can accept, negotiate, or even reject it just like their acceptance of behavioral and lifestyle changes.

Negotiating Urban Lifestyles and Modernity

The experience of converting to Islam and becoming a hijrah Muslim, while at the same time engaging with communities in urban environments, encounters multiple tensions with lifestyles and modernity. Most of those who started out with a passion for learning about Islam and practicing Sharia in their daily lives face complicated transitional periods challenging their ability to negotiate the complexities of urban life. On the one hand, identity has an important place in their spiritual experience, especially since it is closely related to the way it is reflected (O’Brien 2006, 327). On the other hand, they are faced with efforts to conform to the views and expectations of their social environment, including family, friends, and relatives.

Modern city life, where lifestyle is the dominant culture, culture, initially poses a major challenge for mualaf and followers of hijrah. However, my interlocutors in the mualaf and hijrah communities acknowledged that the understanding of Islam they gained from actively attending Quran recitals did not prevent them from later embracing urban lifestyles. Under the guidance of their asātīdh, they construct an understanding of lifestyle and modernity as part of the field of Islamic propagation. Therefore, the campaign to be Muslim while still being able to look trendy is one that flexes their Islamic identity as they negotiate lifestyle and modernity. Noorhaidi Hasan refers to this phenomenon as the emergence of an Islamic pop culture, where Islam has become integrated into a wide consumer culture and serves as a significant marker of identity, social status, and political affiliation (Hasan 2009, 231). Moreover, community activists with celebrity backgrounds serve as role models for them in becoming Muslims, especially for women who always look fashionable and can even appear luxurious even with a wide hijab (a common term in Indonesia to denote a form of hijab that covers the shoulders up to the chest). As for men, the idea that Muslims must dress in Middle Eastern-style qamis (robe) and maintain a beard is not a necessity. Most of the men I spoke to did not display any prominent Islamic symbols.

The preaching of Islam to the mualaf and hijrah community, therefore, is not exclusive in the sense of shutting them off from urban culture. In some places, exclusivity in religion is evident, such as choosing to live in or own housing labeled as Islamic, as has become a trend in several cities. An ethnographic account by Hew Wai Weng highlights the significance of urban Islamic place-making as an endeavor undertaken by Muslims, especially the middle class, to maintain a consistently negotiated and contested practice of Islamism (see Hew 2017). However, this is not a common element among followers of the hijrah movement and mualaf. The realization that every aspect of life is an opportunity to preach Islam underlies their efforts to deal with the tension between Islam, modernity, and lifestyle.

Nonetheless, the newly embedded Islamic values become their moral axis in navigating every tension that arises both in work and daily life in urban society. When struggling with the routine of work, for example, they do not neglect obligations such as the five daily prayers, Friday prayers at the mosque for men, obligatory fasting, reading the Quran, and attending recitations. They also admit that their work environment is generally supportive for Muslims, especially when they want to worship. In other words, the diversity and pluralism celebrated in the city make it easier for mualaf and those who have performed hijrah to balance their work and faith. Simultaneously, integration into urban culture while maintaining Islamic identity involves finding commonalities while respecting differences.

The same applies to the utilization of technology, which plays an important role in urban life. Today, urban Muslims heavily rely on smartphones, for example, for all their religious activities such as prayer time reminders, Quran apps, or searching for halal foods on various online platforms. Moreover, the promotion of hijrah on social media and the accounts they follow on Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok also guide them, including mualaf, to always be exposed to Islamic content such as recitations. These platforms also provide space for self-actualization and participation in public life. By actively engaging in social media, they find space to share their concerns amidst the complexity of urban life. This is also evident in updating the recitation schedules at the mosques they regularly attend. Currently, in big cities such as Jakarta, Bandung, and Yogyakarta, regular recitations at mosques are easily accessible. By participating at these mosques, mualaf and followers of hijrah can not only navigate the fast-paced city life but also maintain strong bonds of community, brotherhood, and kinship. Thus, support and a sense of belonging grow among them. In this context, Anthony Giddens’ concept of “ontological security” becomes relevant, as mualaf and followers of hijrah strive to maintain a stable sense of self in an ever-changing life, sometimes grappling with anxieties related to identity, belonging, and authenticity as they negotiate urban life (Kinnvall 2004; Giddens 1984, 64).

Therefore, in urban environments characterized by the convergence of diverse cultures and belief systems, mualaf and hijrah followers not only, in Weber’s terms, rationalize religion in modernity as a response to disenchantment with the world, but also face cultural tensions as they try to reconcile their faith with the city’s increasingly secular and pluralistic character. These tensions manifest in various aspects including dress preferences, food choices, and worship, as mentioned above.

Unique Islamic Identity and Contestation with Other Groups

The experiences of mualaf and followers of the hijrah movement play a pivotal role in shaping a distinctive Islamic identity in Indonesia’s diverse and dynamic Islamic landscape. In its historical setting, Indonesian Islam, until recently, has been categorized in various ways by scholars, employing dichotomous terminologies to understand religious practices, such as mysticism and activism (Drewes 1955), modernists and traditionalists, abangan (nominal) and santri (pious Muslims), textual and substantialist (Liddle 1996), or conservative and liberal (Anwar 2009). The hijrah movement, which has contributed to an increase in the number of mualaf over the past two decades, adds another layer of diversity to the fluid and complex face of Islam, especially in everyday religious life.

With different leitmotifs and narratives of conversion experiences, mualaf and hijrah participants base their spiritual journeys on notions of kinship deeply rooted in Islamic tradition—where believers are brothers—as they voluntarily, confidently, and passionately commit to group involvement and never abandon regular recitations. This has been a powerful catalyst for the formation of a distinctive Islamic identity, emphasizing the promotion of Ukhwah Islamiyah (Islamic unity and brotherhood) and imagination towards the ummah. However, in practice, the spiritual experience of becoming pious Muslims has been subject to tensions, involving family, society, and even fellow Islamic communities from different groups.

Some of my interlocutors who were mualaf or active in hijrah groups admitted how they sacrificed and re-adapted their lifestyles and worldviews when they decided to return to Islamic ethics and morals and be disciplined in practicing Islam. The sacrifices are believed to be an ethical consequence of increasing their faith and piety. For example, one hijrah follower who has a family was willing to leave his job earning well above the national minimum wage simply because the company he worked for supported practices that were against Islamic law, such as usury and same-sex relationships. On the contrary, being part of a hijrah group, he found warmth, sanctuary, and solidarity among group members before awakening awareness in carrying out the mission of daʿwah Islam, even with an income equivalent to the minimum wage, and similar stories can be found in many hijrah groups. Such collective experiences, sacrifices, and efforts to maintain commitments create a binding sense of camaraderie and kinship among mualaf and hijrah followers while in the group. At the same time, it reinforces their identity as hijrah Muslims, where hijrah itself has become an identity for Indonesian Muslims, distinguishing them from other Islamic groups.

In addition to engaging in groups, mualaf and followers of hijrah also have a collective image of Islam in relation to the global community. Borrowing the concept of the imagined community, as articulated by Benedict Anderson (Anderson 2006; Gole 2002), they envision Islam as having the capacity to shape and be shaped by a larger Muslim community, both locally and globally, with digital capital behind it. It is also evident how the Islamic community has evolved over time where there is dynamism, diversity, and global interconnectedness (Laffan 2003; Ho 2006; Tagliacozzo 2009). To realize this ummah imagination, they create a common cultural and historical narrative among Islamic communities both in Indonesia and in other countries. For example, activists of hijrah groups and the mualaf community build a narrative that Islam is one, as exemplified by the Prophet Muhammad; there is nothing different around the world. They therefore tend not to accept other designations, such as moderate Islam, liberal Islam, Islam Nusantara, etc., which in their view would only compartmentalize Muslims. In 2018, for example, hijrah asātīdh gathered and held a grand daʿwah event entitled “Muslim United,” which later grew into a hijrah community with significant followers. Therefore, in Indonesia, the ummah ideal is quite strong among hijrah activists and asātīdh, in addition to uniting the power of Islam so that Muslims can more easily contribute to social problems.

However, the realization of ummah often diverges from the idealized notion of unity. Instead, it is characterized by diversity and fragmentation, particularly in Indonesia. The history of Islamic development in the region underscores the challenge of achieving a unified voice. Despite efforts to foster a sense of communal belonging, such as through initiatives like the Barisan Bangun Negeri, an association of hijrah asātīdh and mualaf, individuals do not necessarily solidify collective attitudes and choices. In essence, the concept of a monolithic Islamic community allows for fluid interpretations and understandings (Mandaville 2003, 23; Zaman 2002, 3; Krämer and Schmidtke 2006, 100:15), as observed when mualaf and followers of hijrah listen to sermons from asātīdh. They can choose to follow or negotiate daʿwah messages based on their perception of authority and their compatibility with personal practices and beliefs. This decision-making process is often influenced by individuals’ cultural backgrounds and personal experiences, contributing to the unique construction of their religious identity. Consequently, there exists a reciprocal and dynamic relationship wherein individuals and the collective shape each other in an ongoing and interdependent manner. Meanwhile, the authority of asātīdh often leads to fragmentation within hijrah groups due to their diverse backgrounds and Islamic viewpoints, which may include being mualaf, having affiliations with groups like Hizb-ut-Tahrir, aligning with ideologies such as Salafism or Wahhabism, or having formerly been celebrities. These dynamics are closely intertwined with Muslim identities and communities, ultimately impacting not only religious authority but also political activism and cultural adaptation.

The endeavor to strive for the re-realization of the ideals of the ummah within the narrative of the hijrah movement continues to be a response to the decline of Muslims in the global arena, alongside disillusionment with the nation-state order, which has failed to achieve the welfare of its citizens. Despite the fluctuating fortunes of these ideals since the late nineteenth century, it is evident that the concept of the ummah can strongly resonate within existing Islamic groups, including national Muslim communities, especially during periods when the narrative of Islamic revival gains momentum in countries grappling with their respective internal challenges. However, on the flip side, this movement, later labeled as Islamism, has failed to garner significant traction in Indonesia, due to multiple factors.

In Indonesia, ever since Muslims emerged as a significant force in politics (Wanandi 2002), a plethora of conflicts have simmered among various groups, spanning both practical and discursive dimensions, aimed at securing influence within society and access to power (Bourchier 2019; Burhani 2018; Barton, Yilmaz, and Morieson 2021). This competition often appears to be vertical rather than horizontal, with the state taking a leading role through policies that often neglect to accommodate the diverse aspirations of Muslims. For instance, the government launched a vigorous campaign for religious moderation in 2018, focusing on practices aligned with the principles of the middle path, Pancasila, and the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. Consequently, the Indonesian government swiftly disbanded Hizb ut Tahrir Indonesia (2017) and the Islamic Defenders Front (2020), citing their alleged opposition to Pancasila and perceived threats to democracy, security, and stability. In response, Islamic groups sometimes act as proxies for the state in “judging” other groups deemed different. Consequently, besides the absence of a static or fixed Islamic identity, particularly for new groups like hijrah and mualaf, the propagation of in-group and out-group narratives has become increasingly conspicuous. Consequently, the imagination of the ummah has become fragile and fragmented, with spaces for dialogue and deliberation notably absent.

Conclusion

Some important points this article has considered are how the phenomenon of the hijrah movement, signifying conversion within the Muslim faith, has influenced the increasing number of converts to Islam in Indonesia over the past two decades. Some Christian converts have not only established communities of mualaf but have also networked with hijrah groups and become popular asātīdh among Indonesian Muslims, especially in urban areas. Through these networks of recitation-based groups in major cities, mualaf and followers of hijrah jointly campaign for hijrah as a piety movement, emphasizing the strengthening of Islamic worship to navigate the complex challenges of life.

With creative Islamic daʿwah and recitation materials that address everyday problems, hijrah groups and mualaf communities have become spiritual sanctuaries for those experiencing individual and social crises and moral collapse. These groups also provide a place to learn about Islam. In these settings, members find solidarity, which shapes their identity as hijrah Muslims. Additionally, a spiritual kinship is formed among them and with their asātīdh through religious rituals and close friendships. This kinship is rooted in the belief that hijrah requires a struggle and that it is better to be part of a group, preaching Islam together with other Muslims. This belief is further supported by Quranic verses about ukhūwah (brotherhood), which hijrah asātīdh and activists emphasize by building the ummah narrative in response to social, economic, and political problems in the country and the broader Islamic world. Therefore, although the hijrah movement seems to prioritize spiritual and moral objectives, it inevitably engages in contestation to gain influence in society, especially with traditional Islamic groups. Moreover, activists and asātīdh of the hijrah movement are aware of their capacity to mobilize many people for political and economic interests amid the significantly growing religiosity of urban Muslims.

This contestation emerged along with the failure of the state to accommodate the diverse voices of Islamic groups that flourished after the Suharto regime stepped down more than two decades ago. The increasingly multi-voiced articulation of Muslims since the emergence of the hijrah movement has been met with restraint and even dissolution, often allowing friction between groups to occur under the pretext of upholding Pancasila, security, and religious moderation. It is important to note that these actions are more rooted in prejudice and state propaganda that portray the trend of Islamic conservatism in black and white. In fact, the goals among the groups campaigning for hijrah are not uniform; some are even contradictory. Therefore, this article not only provides insight into the dynamics of conversion to Islam in contemporary Indonesia through the lens of the Islamic piety movement but also underscores the importance of understanding these dynamics in a broader context. This understanding is crucial to preventing over-reactive attitudes from both Islamic groups and the state towards emerging religious trends.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the editors of this special issue, particularly Sebastian Rimestad and Minoo Mirshahvalad, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback and insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article. I am also grateful for the generous financial support from the Katholischer Akademischer Ausländer-Dienst and a grant from the École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), which made the fieldwork for this article possible.

References

Based on data from the Ministry of Home Affairs as of December 31, 2021. The second position is for the Christian population of 20.45 million (7.4 %). As many as 8.43 million Indonesians are Catholic (3.1 %). There are 4.67 million Hindus (1.7 %), 2.03 million Buddhists (0.7 %), and 73,635 people follow Confucianism. 126,515 Indonesians adhere to the Aliran Kepercayaan (ancestral religion) (source: https://dataindonesia.id/varia/detail/mayoritas-penduduk-indonesia-beragama-islam-pada-2022, accessed May 1, 2023).↩︎

Muhammadiyah was founded in 1912 in Yogyakarta with the aim of adapting Islam to modern Indonesian life. The organization was inspired by the Egyptian reform movement led by Muḥammad Abduh, which sought to bring the Muslim faith into harmony with modern rational thought. Meanwhile, Nahdlatul Ulama was established in 1926 in East Java with a religious outlook that is considered “traditionalist,” as it tolerates local culture as long as it does not conflict with Islamic teachings. It grew in rural areas, based on pesantren, i.e., Islamic boarding schools, and clerical figures known as Kiyai.↩︎

Pancasila is a doctrine that consists of five principles, which are succinctly stated in Indonesian, but are often somewhat ambiguous when analyzed in depth and certainly less suggestive when translated into English. The doctrine was ratified at the Session of the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence on August 17, 1945, the day after Indonesia’s independence. At this session, Pancasila was included in the preamble of the 1945 Constitution and became the legal basis of the country. The first principle (or sila) is the belief in one supreme being (Sila Ketuhanan yang Maha Esa). The second principle is variously described as a commitment either to internationalism or more literally to just and civilized humanitarianism (Sila Kemanusian yang Adil dan Beradab). The third sila expresses a commitment to Indonesia’s unity (Sila Persatuan Indonesia). The fourth sila emphasizes the idea of a people led or governed by wise policies arrived at through a process of consultation and consensus (Sila Kerakyatan yang Dipimpin oleh Hikmat Kebijaksanaan dalam Permusyawaratan/Perwakilan). The fifth sila expresses a commitment to social justice for all Indonesians (Sila Keadilan Sosial bagi Seluruh Rakyat Indonesia) (see Morfit 1981).↩︎

Suharto’s rise to power and the New Order regime in the mid-1960s occurred against the backdrop of massive anti-communist purges taking place across Indonesia. Estimates of the number of people killed during this period vary widely. Suharto took advantage of the anti-communist sentiment to portray himself as a strong and stable leader who could restore order. In March 1966, Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, issued a decree giving Suharto the authority to restore order and stability. Suharto used this authority to purge the remaining elements of Sukarno’s government, and in March 1967, he became the acting president. In 1968, Suharto officially became the president of Indonesia, a position he held until his resignation in 1998.↩︎