From Manichaeism to Zoroastrianism

On the History of the Teaching of the ‘Two Principles’

The essential feature in the religious history of Pre-Islamic Iran is its dualistic worldview. It marks all stages of Zoroastrianism and also Manichaeism, in which dualism can be regarded as the most important Zoroastrian piece of inheritance. The following essay concentrates on two aspects of this ‘inheritance’ that have been overlooked until today: 1) The Manichaean dualism is consistently built on elements and tendencies that already existed, albeit covertly, in the Younger Avesta; and 2) The Manichaean dualism has thereby confronted Zoroastrian theologians with the task of giving an alternative and consistent formulation of dualism. Thus, the continuous attention both Dēnkard III and the Škand Gumānīg ī Wizār, two of the most philosophically inclined works in Pahlavi, give the concept of dualism seeks to articulate a relation between the notion of evil and the idea of the “finite,” and also to formulate the notion of “principle,” seen as a demarcation from the Manichaean solution.

Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, dialectical development of dualism

Preliminary Remarks

In ancient times the Persians worshipped Zeus and Cronos and all the other divinities of the Hellenic pantheon, except that they called them by different names.1 […] But nowadays their views conform for the most part to those of the so-called Manichaeans, to the extent of their holding that there are two first principles one of which is good and has given rise to all that is fine in reality and the other of which is the complete antithesis in both its properties and its function. They assign barbarous names drawn from their own language to these entities. The good divinity or creator they call Ahuramazda, whereas the name of the evil and malevolent one is Ahriman. (Agathias, Hist., 2.24.8–9; translation by Frendo in Agathias 1975)

The most characteristic religious feature of pre-Islamic Iran is the embedding of its theology in an ontological, cosmological and also ethical dualism. This holds true for Mazdaism/Zoroastrianism (second millennium BCE until today) (in the following: ‘Zoroastrianism’), but also for Manichaeism (third century CE until the early second millennium). Both religions, Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, seem to regard themselves as religions of the “two principles” (MP dō bun(ištag)). While in Manichaeism, dō bun is an emic term from the times of Mani, which the religious founder applied to the kernel of his religion during the days of his stay at the court of Šābuhr, it remains to be examined when a comparable conceptual reflection of the philosophical fundamentals took place in Zoroastrianism, and how it is related to the Manichaean solution. The two ‘philosophical’ books of the Zoroastrian Middle Persian literature, Dēnkard 3 (early ninth century) and Škand Gumānīg Wizār (probably middle of the ninth century), show that reflection about the dualistic conception of being was the key topic of Zoroastrian intellectuals.

Because of the significantly higher age of Zoroastrianism, it is (and was already in the early Islamic period) communis opinio that the Manichaean dualism is a reformulation of the Zoroastrian one. Although this opinion certainly includes a kernel of truth, it needs at least some complements. First, one needs to inquire about the relation between the Manichaean dualism and the dualism of the Avesta. It seems to me that the Manichaean dualism draws the radical conclusion from a Younger Avestan structural tendency. Secondly, one cannot help thinking that late antique and early Islamic Zoroastrianism came to a new shaping of its dualism under the influence of the Manichaean conception, i.e., that the Zoroastrian concept/term dō bun(ištag) is a reaction to the Manichaean concept/term dō bun. In addition to the assumption of such an external demarcating process, one should inquire both about the internal considerations and the theological-philosophical models late antique or early Islamic Zoroastrianism adopted to solve the problems generated by its own critique of the Manichaean dualistic model.

Thus, my paper tries to explain the genesis of the Iranian religion(s) in the late antique and early Islamic period on the basis of three dynamic elements: 1) religious competition and demarcation; 2) theoretical considerations within one religion; 3) the adoption of philosophical models.

On MP bun(išt)(ag) “principle”

The MP word bun (bwn) goes back to OIr *buna-/būna- (OAv būna-; YAv buna-) < *budna-, cf. Ved budhná- m.2 This *bu(d)na- has the same meaning as its cognates Gr πυϑμήν m., Lat fundus or Germ Boden, “ground” and – cf. MIndic bundha- n. – “root.” The word designates low-lying things/places. In the Younger Avesta the meaning “ground (of the waters)” dominates.3 It seems that the Avesta only paves the way for the later meanings of “beginning,” “principle.” In Y 53.7, the būna- (Loc būnōi.) “vagina” or “uterus” is probably the place of the mainiiuš. drəguuatō. (cf. Y 30.5 aiiā̊. mainiuuā̊. … yə̄. drəguuā̊.).4 V 19.47 uses an expression bunəm. aŋhə̄uš. təmaŋhe. “(to the) ground of the dark existence,”5 i.e., the place of the demons. Especially this bunəm. aŋhə̄uš. təmaŋhe. is instructive because it points to a connection of “the deep place” and the place where the evil beings live.6 The deep place is also understood as the place without light (see PahlTr V 19.47). So buna- appears as the kernel of a semantic cluster designating deepness/evil/lightlessness. Even though the semantic inversion of this cluster already exists in the Avesta, the word buna- is not applied to these two clusters as a general term. From the evidence of the Avestan sources, we must conclude that a more abstract meaning of bun(a-) as “fundament; source7; principle” was not developed before the post-Avestan period.

The Zoroastrian sources from the period between the end of the Avestan text production8 and the Pahlavi texts of the ninth century are not numerous.9 The best and oldest information on the religious development in the post-Achaemenid period comes from the Greek Nebenüberlieferung and points to a usage of *bun(a) as “principle” in the fourth century BCE. Eudoxos10, Theopompos11 and Hermippus12 spoke of “two principles”13 (δύο … ἀρχάς) (cf. Gnoli 1974, 141) that were called Oromazdes and Areimanios by the Magi (Diog. Laert., Vit.Philos., Prooem. 6,8). Aristotle (384–322) uses δαίμων (≈ Av mainiiu-) as the generic term for two opposing transcendent beings of the Iranian religion.14 He designates both the ἀγαϑὸν δαίμονα as well as the κακὸν δαίμονα as the ἀρχάς:15

| Ἀριστοτέλης δ’ ἐν πρώτῳ Περὶ φιλοσοφίας καὶ πρεσβυτέρους εἶναι τῶν Αἰγυπτίων· καὶ δύο κατ’ αὐτοὺς εἶναι ἀρχάς, ἀγαθὸν δαίμονα καὶ κακὸν δαίμονα· καὶ τῷ μὲν ὄνομα εἶναι Ζεὺς καὶ Ὠρομάσδης, τῷ δὲ Ἅιδης καὶ Ἀρειμάνιος. φησὶ δὲ τοῦτο καὶ Ἕρμιππος ἐν τῷ πρώτῳ Περὶ μάγων καὶ Εὔδοξος ἐν τῇ Περιόδῳ καὶ Θεόπομπος ἐν τῇ ὀγδόῃ τῶν Φιλιππικῶν | Aristotle in the first book of his dialogue On Philosophy declares that the Magi are more ancient than the Egyptians; and further, that they believe in two principles, the good spirit and the evil spirit, the one called Zeus or Oromasdes, the other Hades or Arimanius. This is confirmed by Hermippus in his first book about the Magi, Eudoxus in his Voyage round the World, and Theopompus in the eighth book of his Philippica.16 |

It is likely that the Middle Persian dō bun(ištag) corresponds to Gr δύο … ἀρχάς. These “two principles” are identified as Ohrmazd and Ahreman by the Greek authors. A philosophical usage of ἀρχή (“principle”) in Greek can be traced back to Anaximander (first half of the sixth century BCE), who called his highest concept, the ἄπειρον “the infinite”, an ἀρχή. Simplicius (in Phys. 150.23; cf. Aristoteles, Metaph. 983b11), says that it was indeed Anaximander who introduced the term ἀρχή (πρῶτος τοῦτο τοὔνομα κομίσας τῆς ἀρχῆς). This is remarkable because a) there is evidence that Anaximander’s ἄπειρον and cosmology is the philosophical reformulation of an Iranian cosmological model (Burkert 1963),17 and b) the topic of the “infinity of the principle(s)” is also known from the Bundahišn, a late antique text that probably has its roots in the Avesta (see below).

The next occurrence of the term “two principles” is (and probably not by chance) the title of Mani‘s Šābuhragān, dw bwn ʿy šʾbwhrgʾn.18 Parthian texts testify an expression dw bwn wrzg “the two great principles,” which is a designation of the fundamental dualism of the cosmos (see GW 111 (§22,3) and the expression Parth. dw bwngʾhyg/dō bunγāhīg). Parthian bun (bwn) and bunγāh (bwngʾh, bwnγʾh) “base, foundation” corresponds to MMP bwnyšt “origin, principle, foundation.”

In ZMP texts, the word bun has more or less the same meaning as Avestan buna-/būna-, “beginning;19 base, root, source” (in the simplex and in the first member of a compound). Only Dk 3 and ŠGW uses rarely the expression dō bun for “the two principles” (see Dk 3.383; 3.414; ŠGW 10.39 [cf. 11.383] bun. i. du., 10.42, 11.327 du. bun.20).21 The ‘abstract’ meaning “principle” is the common meaning of the enlarged form bun-išt(-ag)(-īh) (Pāz. buniiaštaa.). This enlarged word-formation and its ‘abstract’ meaning is unknown in the Pahlavi Vīdēvdād,22 a Zoroastrian work from the Sasanid period (Cantera 1999, 2004), probably because of the translator’s intention to avoid anachronistic interpretations of Avestan words.23

Mani, the perverter of the Abestāg and Zand …

From the information given by the classical authors, we can deduce that, at least beginning with the second half of the first millennium BCE, a term “principle” and a concept “the <teaching of the> two principles” existed in Iran. The prominent position, however, that Mani granted to the above term and the concept in the third century CE certainly influenced their further development and contextualization in the Zoroastrian theology.

Mani appeared, to his Zoroastrian counterparts, as a perverter of the holy Zoroastrian texts. According to a passage in Dādestān ī dēnīg, one of the seven Zoroastrian arch-sinners is the ahlomōγ (= frēftār “deceiver”). This “confuser of Aṣ̌a” (this is the literal meaning of ahlomōγ, a loan from Av. arta-maoγa-) is, according to the paraphrase of the term in Dd 71, the one who wardēnīd abestāg ud zand “perverted abestāg ud zand” (the holy texts which Dd 71 also calls weh-ahlāyīh “<the acts of> the Good Truth”). He is accused of a kind of ‘forgery’ of the religious writings (ayāddān):

| ēk ān kē-š ahlomōγ-dēnīhā kāmist ō dād ī stōd ēg pad frēftārīh wardēnīd abestāg ud zand az xwēš wimand | One is he by whom the heretical religious teachings (dēnīhā) were preferred as the dād ī stōd; he perverted then (on that basis) through deceitfulness the Abestāg and Zand according to his own definitions.24 |

The text does not provide the identity of the ahlomōγ, most likely because the intention of the Zoroastrian author was to establish a “mythical model of a heretic.” This model fits the great ‘heretics’ of the Sasanian period, Mani and Mazdak, very well, however. The lexicon of Manichaean Middle Persian, Parthian, and Sogdian includes a good number of loan words from the Zoroastrian context (see Colditz 2005). It seems that Mani had access to the (still unwritten?) Avesta (see Cantera 2004, 106–53),25 probably in its Pahlavi translation(s). To give just one example: the Parthian Gyān wifrās (GW §21), edited a few years ago by Werner Sundermann, mentions a “Nask” with the name “the Living Nask” ((n)s(g) jywʾng). This Nask – jywʾng26 is perhaps a folk-etymological interpretation of Zand (cf. Herders and Kleukers “Lebendiges Wort”27) and points to the five “god”s (yzd) which represent the five elements and bear the names of the Gāϑās:

| GW §32 | GW §46 | GW §65 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʾrdʾ(w) [frw](r)dyn | wʾd yzd | rw(š)n [y](zd) | ʾb (yz)[d] | ʾdwr yzd |

| ʾwhnwyt gʾẖ (M838 R 9 = M419+M3824 R 3) | ʾwyštwyt gʾẖ (M248+ R 14 = M890 R 2) | whwxštr gʾẖ (M295 R 8 = M6090 R 4) |

Gyān wifrās illustrates a typical aspect of Manichaean textual technique, namely the reference to the Avestan texts (probably in their Zand-form) and the combination of their names with new elements, in the case of the Gyān wifrās Aristotelian-Manichaean elements. This combination, suggested and enabled by the occurrence of the number 5 (five Gāϑās/five Manichaean elements), could possibly make a Zoroastrian critic believe that it led the Manichaeans to an esoteric interpretation of the most ‘holy’ Zoroastrian texts, and, as such, that it ‘perverted’ the ‘true’ Zoroastrian understanding of the Gāϑās.

… And its Executor

If we leave aside this contingent reinterpretation (an insider would have seen it as ‘perverting’) of more peripheral Zoroastrian terms and concepts, and take into consideration the conceptual kernel of Manichaeism, that is, the teaching of the ‘dō bun,’ we could describe Mani’s teaching as the fulfilment of metaphorical-conceptual tendencies that can be found only in the Avesta. The key difference between Manichaeism and Zoroastrianism is the Manichean identification of hyle (“matter”) with Evil, which leads to a simplification of the Zoroastrian double dualism of good/evil and material/immaterial.

| Manichaeism | Zoroastrianism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| material = | - | non-material = | material (gētīg) | - | non-material (mēnōg) | |

| dark = | - | light = | dark = | - | light = | |

| evil | - | good | evil | - | good |

In the Younger Avesta and in late antique Zoroastrianism, we can observe that the formula dark=evil presents connections to matter (although it has essentially only a mēnōg-existence,28 it nests parasitically only in the material world), whereas the formula light=good carries allusions to the non-material (aṣ̌a “truth” is light, see Y 37.1). Nevertheless, the relationship between dark=evil/light=good and gētīg/mēnōg is more complex in Zoroastrianism than in Manichaeism. Historically, it indicates two different ways to situate these terms in different constellations.

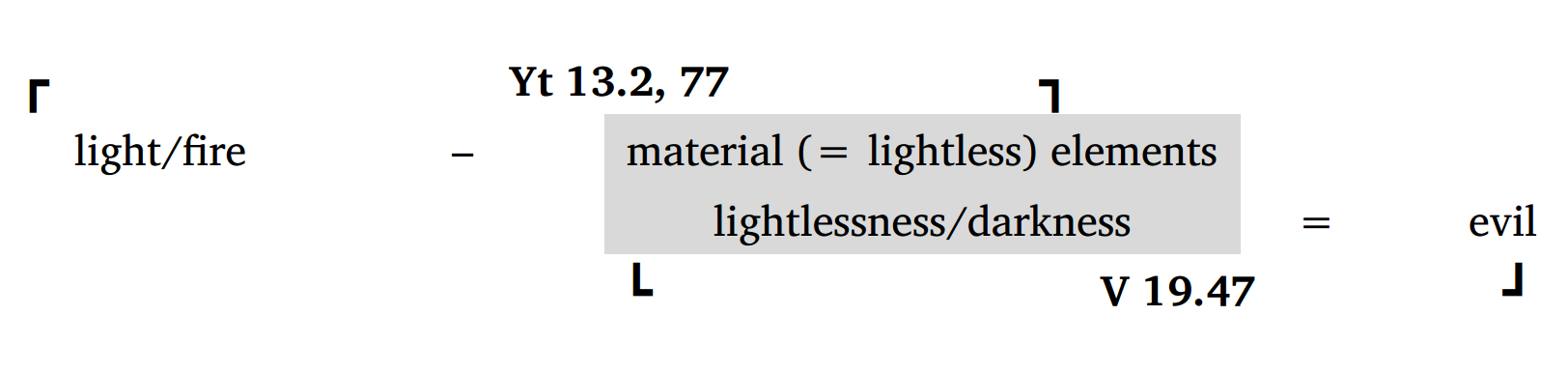

As we have seen in V 19.47, the Younger Avesta is already acquainted with the semantic cluster of “deep = lightless / evil.” In Manichaeism, this cluster seems to be enlarged by the element of “matter.” The tertium of both, matter and Evil, is very probably lightlessness/darkness. In Avestan Zoroastrianism, in particular in the cosmology of Yt 13 and (then) Bundahišn, lightlessness is, at least implicitly, the logical consequence of the theological decision to separate light from the other (six) ‘elements’ and to oppose it to them.

Thus, Manichaeism creates, one might say, its theory by a superimposition of two (explicit or implicit) Avestan equations:

- V 19.47 lightlessness/darkness = Evil

- Yt 13 light/fire is separated from / opposed and superior to the other material elements (> light contra material elements)

The scheme of the superimposition is depicted in figure 1. The combination of Yt 13 and V 19 has a further implication. If “evil” is “lightless”, and if “lightless” is “material” (“tactile” according to the later Zoroastrian epistemology29), then the inversion of the argument leads to the conclusion that the immaterial is the light which is goodness.30 Mani’s worldview is consonant with notions preformed in the Younger Avesta: the identification of light with goodness and its opposition to matter. It was, as we shall see, the task of the late antique Zoroastrian theology to find arguments against Mani’s conclusion, but also to explore ways not to radically separate light from matter.

The Zoroastrian Critique of the Manichaean dō a-bun Conception…

It is remarkable that Mani’s radical theological-philosophical conclusion was not adopted by late antique Zoroastrianism. Yet it is a conclusion that tends to be drawn in Zoroastrian cult practices, for instance, in establishing an eternal/unpolluted fire. In the more trivial forms of Zoroastrian cosmology (see, e.g., MX 1.31-32), one could also identify a correlation between gētīg (material) and world with demons, and, on the other hand, mēnōg (spiritual) and world without demons. My explanation for this Zoroastrian non-fulfilment of what can probably be described as an overarching historical tendency—the cultural increase of abhorrence of the materia—is that a) a radical abhorrence of the materia can produce economic problems,31 and b) the dualistic competitor already drew a radical conclusion, that is, the damnation of the material world. According to the latter hypothesis, the Zoroastrian priests of both the pre-Islamic and the Islamic period had to find arguments against the Manichaean dualism (or against any dualism of ‘Manichaean’ expression), and to formulate a dualism in which light, darkness, and matter could be set as an alternative and convincing constellation.

The Zoroastrian key argument against the Manichaean identification of materia and darkness/evil is that by such an identification, the materia necessarily appears as something infinite, as one could see from Ādurbād’s argument in Dk 3.199.7 against Mani’s teaching in Dk 3.200:32

| gytyk pṯ’ bwnyštk’ AL YHSNNyt MH̱ +dgl33 LA YHWWNt’ | gētīg pad buništag ma dārēd cē dagr nē būd | Do not claim that the gētīg is a buništag because it was/is not ‘long/eternal’!34 |

Ādurfarrbay discusses the teachings of the Jews, the Manichaeans, and the Sōfistās in Dk 3.150 (a chapter dated to the early ninth century). The text claims that the Sophists teach a general a-bun, i.e., non-creation of the whole being.35 In the following, the term a-bun is also applied to the Jewish and even to the Manichaean position36 (where we would rather expect the use of bun, buništag, see B 169.5f., and in particular the self-designation of Manichaeism as the religion of the dō bun* [see above]).37 The following text presents the Jews as declaring the necessity and possibility of one and only one a-bun (a monotheistic position). The Manichaean teaching of dō a-bun is presented and criticized as follows:

| W TLYN‘ ʾbwn y KRA ʾywk‘ pṯ‘ tn‘ ʾsʾmʾn‘ cʾštk‘ mʾnʾyk ʾndlg ẔNH̱c AYK AMT ʾywk’c y pṯ‘ tn‘ ʾsʾmʾn‘ YHWWNt‘ LA šʾstn’ MNc AYT’yh y ywdt‘ ʾcš tn‘ʾnc pytʾk TLYN y KRA ʾywk pṯ‘ tn‘ ʾsʾmʾn‘ YHWWNt‘ cygwn šʾyt‘ | ud dō a-bun ī har ēk pad tan- āsāmān cāštag <ī> mānāī andarag ēn-iz kū ka ēk-iz ī pad tan-āsāmān būd nē šāyistan az-iz astīh jud aziš tanān-iz paydāg dō ī har ēk pad tan-āsāmān būd ciyōn šāyēd | And <concerning> the teaching of Mānāī ‘<There are> two a-buns, each exists in/through the body-sky39’. The objection is the following: If it is impossible that only one <a-bun> exists in/through the body-sky—and <the existence of such an a-bun is> evident from a being apart from the bodies (?40)—, how should it be possible that each of the two <a-buns> exists in/through the body-sky? |

It seems that the Manichaeans are not criticized for their definition of dō bun as dō a-bun, in the sense of “what has no beginning.”41 For Ādurfarrbay, a true bun (see above B 169.5f.) is infinite (i.e., an a-bun “what has no beginning” is the definition of bun “principle”). Ādurfarrbay’s general argument seems to be that an a-bun (= bun) cannot be part of a “body-sky” because it cannot be material, finite.42 In the case of the Manichaeans, he observes that they claim an “infinite materia,” a logical incoherent concept; the report of Šahrastānī (eleventh/twelfth century)43 says that in difference to the “Majūs,” the Thanawīya, and within this school the Manichaeans, claims the infinity of light and of darkness (Haarbrücker 1850–1851, I:285). Šahrastānī’s report on the “Majūs” (“Majūs” is a general term for the three Zoroastrian schools known to Šahrastānī) starts with a comparison of the schools of the “original Majūs” and the Thanawīya (Haarbrücker 1850–1851, I:275–276) shows that their key differences pertain to:

a) the question of an (in)finity of light (= God/goodness) and darkness (= Evil/evil) (all Majūs groups seem to claim a non-infinity of the darkness); and

b) the reconstruction of the mixture of light and darkness.44

… And Its Consequences

Ādurbād’s refutation of Manichaean teachings45 is grounded in its critique of Mānī’s giving the status of “principle” to the material element—which is, in the Manichaean perspective, identical with the evil/darkness. Ādurbād’s logical argument is, as I have indicated above, that one can define as principles only those ‘things’ that take a predicate ‘long/eternal.’ The argument leads to two conclusions. First, the materia cannot be evil, which is, in the Zoroastrian point of view, at least ‘partly eternal’;46 secondly, only goodness and (partly) evil can claim to be ‘principles.’ Ādurbād’s answer to Mānī preserved (or, at least, ascribed to Ādurbād) in Dk 3 is nothing less than the Zoroastrian deconstruction of the fundament of Manichaean theology, a fundament that was also build on Avestan motifs (see above). This deconstruction, however, opens a theoretical gap. Zoroastrian theology must answer the following question: How, then, is the materia related to the dō buništag?

The really sensitive point in the argumentation is the status of light. In Dk 3.150, the Manichaeans are seemingly criticized, as said above, for their perspective on light and darkness as two infinite beings, as dō a-bun. Although Zoroastrian schools (according to Šahrastānī’s report) take different positions with regard to the status of light, they all try to define an ontological difference between the status of light and that of darkness. The general question behind the different Zoroastrian consideration is: Does ‘light’ belong to the material/finite or to the spiritual/infinite world? If we were to rephrase the same question in modern terms, we would ask: is ‘light’ a phenomenon or a concept?47

The dualistic conception in the Bun-dahišn48

The Zoroastrian catechism in Pahlavi CHP/Pand Nāmag replies very concisely to the question asked in CHP 1 buništag ēw ayāb dō “there are one or two principles?”:

| buništag dō ēk dādār ud ēk murnjēnīdār | “the principles are two:50 one is the creator, one is the destroyer51” (cf. WZ 1.21, 28; 22.5)52 |

The most prominent chapters presenting the Zoroastrian teaching of the dō buništag are the cosmogonical introductions of the Wizīdagīhā ī Zādsparam and the Bundahišn. The beginning of the WZ indeed frequently uses the word buništ(ag)(īh), often in problematic spellings (see WZ 1.12 bwšnnst’ (+bwnyšt’) ī tārīgīh “basis of darkness”; WZ 1.15 bwnsyšyt’/bwšyšyt-ē “one (of two) principles”; WZ 1.21 dō bwndhštyh/bwnyštkyh “dualism”; WZ 1.28 bwnyštʾn’/bnyštʾn’ “<both> principles”; WZ 22.5 dōīh ī bwnyštʾn’/wwnyštʾn’ “the duality of the principles”). The beginning of the Bundahišn (Bd 1.1-12)53 is a great cosmogonical tableau that presents the “two principles”. The text54 has at least three interesting aspects:

1) After a quotation from the text of the weh-dēn (probably the translation of an Avestan text) in Bd 1.1, Bd 1.2 starts with a philosophical definition of the essence of Ohrmazd (we find the same textual structure in Bd 1.3+4 with reference to Ahreman).

2) This definition is interesting from the perspective of content since it points to a concept of emanations.

3) The notions of finitude/infinity (kanāragōmandīh/akanāragōmandīh) are the most important subjects of debate in Bd 1.1-12.55

Regarding the first point, general definitions are uncommon in the Avesta, especially definitions that serve as a starting point for further explications (as it is the case with the Bundahišn, a book that takes the reader from the most general categories to particular, accidental events of history). Because it is likely that IndBd and GrBd have a common ancestor56 (most likely in the Sasanian period)—a *Bundahišn—, we can assume that the defining phrases as well as the philosophical features of Bd 1.1-12 are an innovation made in a period between an Avestan pre-text of the Bundahišn and this *Bundahišn.

Regarding the third point, GrBd 1.1, a passage that does not belong to the ‘philosophical stratum’ of Bd 1.1-12, already uses the word “infinite.” According to this text, Ohrmazd exists zamān ī akanārag “for (as?) the infinite time.” The expression zamān ī akanārag is a calque for zurwān ī akanārag “infinite time(-god).” The appearance of that Z/zurwān in the cosmogonical context (cf. WZ 1.27-28) is motivated by the idea of a “pact” between both principles which lasts for 9000 years (see Bd 1.10 and then Bd 1.24 sqq.).57 As we can deduce from MX 8 (cf. WZ 34.35), the Z/zurwān ī akanārag enables the creation of a finite, limited time, the time of the “pact” (paymān, pašt), which is supervised by Mihr (see MX 8.15; cf. Mihr’s role in de Iside 46 as a “mediator” [μεσίτης]). It is, however, remarkable that only GrBd 1.1, but not IndBd 1.1 connects Ohrmazd with the zurwān ī akanārag. Thus, a textual interpolation (from the probably non-original philosophical passages Bd 1.2 etc.) in GrBd seems likely (cf. GrBd 1.7, 1.8). The parallel to Bd 1.1, Bd 1.3 (referring to Ahreman), shows that IndBd 1.3 has a similar textual addition. A gloss says that the existence of evil is ultimately finite (while Ohrmazd is infinite).58

However, the complex philosophical discussion on “finitude”/“infinity” of the two principles in Bd 1.1-12 cannot be explained only in the frame of the figures “zurwān ī akanārag” and “time of the pact”. Since, according to Ādurbād, the notion “bun” implies “infinity” (Dk 3), we must suppose that the whole discussion in Bd 1.1–12 is an attempt both to solve the philosophical problem of two infinite beings59 and to find a way to connect an infinite being with a finite world.

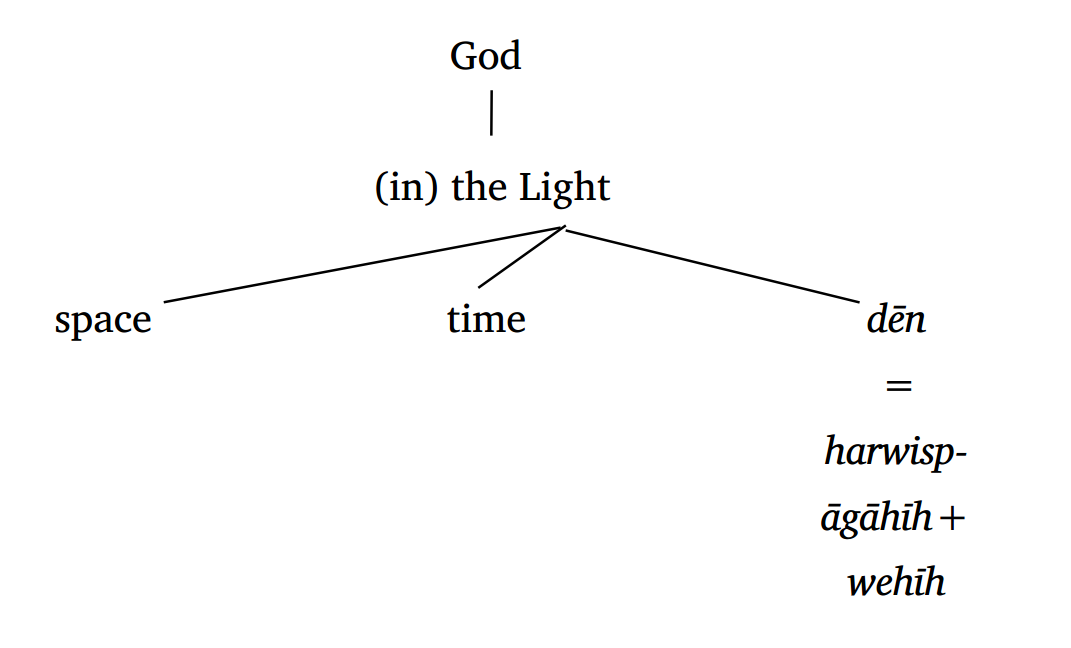

Regarding the second point, it seems that in adopting and discussing the terms “finitude”/“infinity,” the Zoroastrian theologians arrive at the integration of categories that not only belong to a mythological-religious but also to a scientific-philosophical discourse: the categories of time and space.60 While the passage Bd 1.1 still says that Ohrmazd was andar rōšnīh “in the light”, Bd 1.2 explains: a) ān rōšnīh gāh ud gyāg ī Ohrmazd ud ān harwisp-āgāhīh ud wehīh zamān ī akanārag “that light is the time-space of Ohrmazd, and that omniscience and goodness are <for> the Infinite Time”; and b) Ohrmazd ud gāh ud dēn ud zamān ī Ohrmazd būd hēnd “Ohrmazd and the space and the Religion and the time of Ohrmazd exist <always>”. An attribute (Bd 1.1 “in the light”) appears now (namely as gāh, gyāg, harwisp-āgāhīh, wehīh) as part of the substance (Ohrmazd) which is characterized by its eternal existence (zamān ī akanārag). There are three of these ‘substantial attributes’: time, space, “religion” (dēn). Together with Ohrmazd/the light they constitute “the whole” (ān hāmag, IndBd 1.2) of infinite time. It seems that these attributes are conceived neither as names (as Ohrmazd’s names in Yt 1) nor as logical attributes (predicates), but as emanations (of the light, see figure 2).

This more philosophical approach to the concept of “god” in the beginning of the Bundahišn is not an isolated phenomenon. Also the defining beginning of Bd 1 (compare Aristotle’s structuring of a philosophical text), the whole textual structure of the Bundahišn (from the general to the particular), and, last but not least, the critical discussion of terms/concepts (especially in Bd 1.6ff.) record the impact of philosophy on a text that has its deepest roots probably in the Avestan literature. This philosophical impact leads to a risky reformulation of the concept of “god.” As we have seen, the difference of substantia (ousia) and accidens (of subject and predicate) becomes blurred in the beginning of the Bundahišn. The proposition “God is light (“licht”)” changes into “God is Light (“Licht”)” = “Light is God”, and with this change the ontological status of “light” becomes questionable. Avestan theology already knew a particular form of light, the “endless light(s)” (asar rōšnīh ← anaγrā̊ raocā̊ [always in the plural]). The term an-aγra- “endless” indicates that these lights were not seen as part of the material world. This can be concluded from the remarkable phrase Yt 8.48 akarana. anaγra. aṣ̌aonō. stiš. “the infinite, endless being of the aṣ̌auuan (= God).”61 It seems that already in the Avesta, and then again in the Bundahišn, “light” has a twofold being. It is seen as part of both the divine and the material world.

A possible philosophical-theological answer to claiming a twofold existence of “light” was the adoption of an Aristotelian-Neoplatonic world-model.62 In fact, this is what we see at least vaguely in the beginning of GrBd 1 (god / light > space/time etc.).63 More obvious than in the (especially Greater) Bundahišn is the Aristotelian-Neoplatonic impact on Dk 3, a book that, in terms of its whole structure and concepts—far more than it is known in Iranian Studies—is based on a peculiar fusion of Neoplatonic philosophy and the dō buništag conception.64 Neoplatonism was attractive to the Zoroastrian authors because it offered a solution for the conflicts between a) philosophy and theology, and b) god and the world, both of which became prominent in late Antiquity. The emanation model enabled the construction of a coherent world. “Light” is seen as a metaphor of this coherence, but also as a kind of ‘connector of the transcendent/infinite with the immanent/finite.’ The metaphorical value of light is prominent in the last chapter of Dk 3. The transmission of the text of the Dēnkard (Dk 3.420) is compared with a chain of light:

| Chain of light | edition/distortion of the Dēnkard by | |

|---|---|---|

| (hangōšīdag <ī>) rōšnīh ī az bun rōšn | Pōryōtkēšān | time of Zardušt |

| Alexander | ||

| (hangōšīdag <ī> az) brāh az bun rōšn65 | Tansar | early Sasanian |

| Arabs | ||

| (hangōšīdag <ī>) payrōg ī az ān brāh | Ādurfarrbay ī Farroxzādān | early ninth century |

| bām-ē ī az +payrōg ī ān brāh az rōšnīh <ī> bun rōšn | Ādurbād Ēmēdān („Dēnkard of the 1000 chapters66) | tenth century |

More interesting is, however, the chain of light67 in text B 93.15-21,68 a passage that belongs to the important cosmological chapter Dk 3.123. This chapter deals with an ontology that was based on a reformulation of Greek element theory (see Shaki 1970, 279–81). Passage B 93.15-21 is the attempt to bridge the gap between the “endless lights” and the inner-worldly area, the elements and their forces:

| bun-stī ī gēhān baxtag ī anagr-rōšn dādār nazdtom wyzwn’69 () cand paywand payr<ō>g ī az ān rōšn brāh ī az ān payrōg bām ī az ān brāh tā-iz ō ras ud az ras pad dādār āfurrišn rasīdag ō bawišn garm-xwēd gētīy-dahišnān fradom bun | The fundamental being (bun-stī) of the world is a division in which (?) the Endless Light is next to the creator wyzwn’ are some connected: payrōg is from that light, brāh is from that payrōg, bām is from that brāh, until it also <comes> to the ras70, and from ras it comes by the creating of the creator to the being, the hot-moist, the first fundament (bun) of the material creature. |

| az bawišn garm-xwēd bawišn-rawišnīh zahāgān cahār ī ast wād ātaxš āb gil | From the being ‚hot-moist’ is the process of being, the four elements71, wind, fire, water, earth (“clay”). |

az bawišn-rawišnīh bawišn-ēstišnīh ēwēnagān ī āmēxtag az zahāgān ēwēnagān baxtag ō kerbān kerbān <ī> wizārdag pad-iz ōy abdom gētīy-dahišnān kē padiš hangirdīgīhēd gētīy-dahišnān |

From the process of being are the mixtures (ēwēnagān ī āmēxtag) of the state of being (bawišn-ēstišnīh) From the mixtures of the elements there is a distribution to the distinct bodies until <the time> of the last material creatures who make the material creatures complete. |

Other models that could bridge the gap between the two worlds and save the ‘unity of light’ also came into play.

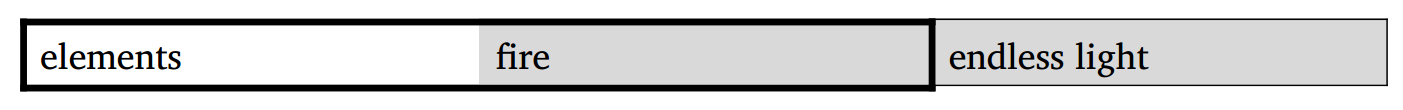

Firstly, in the Bundahišn, the six Zoroastrian ‘elements’ appear in a fixed order: heaven, water, earth, plant, animal, man.72 Moreover, the Bundahišn (at least the Greater Bundahišn) transmits passages in which not only the seventh material element, fire, is mentioned, but in which fire both appears in an outstanding position73 and it is connected to the endless lights74 or the heavenly sphere (see GrBd 6a-j).75 This order indicates a mediating cosmological position of fire. It has neither the same status as the other material elements heaven, water, earth, plant, animal and man, nor does it belong to the same ‘transcendent’ level as the “endless” lights.76

Secondly, in GrBd 7, a system of correspondences is invented. The sublunar elements (see König 2020) correspond to the sequence of heavenly lights77 (Iranian order):

| water | earth | plant | animal | man | fire | sublunar (= subastral) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stars | moon | sun | endless lights | heavenly |

The different models are both attempts to posit a distinction of the spiritual (the divine; the transcendent) from the material sphere and to posit a connection of both spheres. The materia is not light (or darkness), but it is connected with light (and darkness).

It seems that the different models (the emanation model; the model of a last and intermediating element fire; the correspondence model) are answers of Zoroastrian theology brought to the key question of how materia is related to the dō buništag: through light which itself exists as fire and endless lights, as material and immaterial light.78

A Brief Note on the Age of the Zoroastrian Opposition between Light and Darkness

The considerations which late antique/early Islamic Zoroastrianism provided on the relation of a concept “dō bun” to the materia and to the concepts/phenomena “light” and “darkness” were both stimulated by a demarcating critique of Manichaean teaching, and directed thereupon by reflections on the nature of light. This led to the adoption and development of different models that could solve the ontological dilemmas which arose from this critique.

A religiously meaningful dualism between light and darkness has its roots in the Avesta. Since Anquetil/Kleuker’s analysis, Plutarch’s (first/second century AD) text de Iside 47, which elucidates the dark Parthian ages, constituted an object of discussion in Iranian Studies. Previous scholarship, however, never clearly made the observation that the Bundahišn and de Iside 47 share the same sequence of events and describe a process from cosmogony to eschatology. It would therefore not be implausible to assume that Plutarch’s account is based on a pre-Bundahišn.79 Compare the beginning of both texts:

| De Iside 47 | Bundahišn | |

|---|---|---|

| οὐ μὴν ἀλλὰ κἀκεῖνοι πολλὰ μυθώδη περὶ τῶν θεῶν λέγουσιν, οἷα καὶ ταῦτ᾽ ἐστίν. ὁ μὲν Ὡρομάζης ἐκ τοῦ καθαρωτάτου φάους, ὁ δ᾽ Ἀρειμάνιος ἐκ τοῦ ζόφου γεγονώς, πολεμοῦσιν ἀλλήλοις: καὶ ὁ μὲν ἓξ θεοὺς ἐποίησε τὸν μὲν πρῶτον εὐνοίας, τὸν δὲ δεύτερον ἀληθείας, τὸν δὲ τρίτον εὐνομίας: τῶν δὲ λοιπῶν τὸν μὲν σοφίας, τὸν δὲ πλούτου, τὸν δὲ τῶν ἐπὶ τοῖς καλοῖς: ἡδέων δημιουργόν: ὁ δὲ τούτοις ὥσπερ ἀντιτέχνους ἴσους τὸν ἀριθμόν.80 | However, they also tell many fabulous stories about their gods, such, for example, as the following: Oromazes, born from the purest light, and Areimanius, born from the darkness, are constantly at war with each other; and Oromazes created six gods, the first of Good Thought, the second of Truth, the third of Order, and, of the rest, one of Wisdom, one of Wealth, and one the Artificer of Pleasure in what is Honourable. But Areimanius created rivals, as it were, equal to these in number.81 | Cf. GrBd 1.1ff. , GrBd 1.44; WZ 1.1-3 Cf. GrBd 1.53, 3.7, 3.14ff.; 1.55; 5.1 |

It is very likely the YAv literature is responsible for the first systematic delineation of the metaphysics of light and darkness in Zoroastrianism. Already in their YAv ‘edition’ (see Kellens 2015) the OAv texts were set into this light-dark-perspective (see Vr 14-24).82 In the Gāϑic verse-line Y 44.5 kə̄. huuāpā̊. raocā̊scā. dāṯ. təmā̊scā. “Which artist made light and darkness?”, Mazdā still appears as an installer of light and darkness.83 Nevertheless, darkness is already the sphere of those who are deceitful (see Y 31.20); they will have darəgə̄m. āiiū. təmaŋhō. “a long (eternal?) lifetime84 of the dark.” In the Younger Avesta, the words raocah- and təmah-85 (ai. támas-) are assigned to the two transcendent spirits which are, in the Bundahišn, identified with the asar rōšnīh (← anaγrā̊ raocā̊86) and the asar tārīgīh. While we could observe that Av. buna- belongs to the semantic field of the deep and dark, a semantic field that was mirrored (with the result of an emergence of the concept of a high-light87), we now see an inverted process. The “endless lights” in H 2.15 (anaγraēšuua. raocōhuua.) receive a complement, namely the “endless darknesses” (anaγraēšuua. təmōhuua.) in H 2.33, a term that is obviously based on a secondary plural.88

Concluding Remarks

Historiography of Iranian religion has always emphasized that Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism represent two variants of a dualistic worldview. This dualism was seen as a characteristic feature of Iran (within a Near and Middle Eastern field of non-dualistic religions), and Manichaeism was taken as an heir of Zoroastrianism. These perspectives are by no means wrong. However, the article has tried to shift these traditional perspectives slightly. It has pointed out that the Manichaean dualism with its identification of Evil and matter, goodness and light, draws conclusions from tendencies of the theology of the Younger Avesta. In return, the Zoroastrian dualism as it is known from the writings in Pahlavi seems to be the result of a criticism of these Manichaean conclusions. In any case, the Manichaean doctrine forced Zoroastrianism to a self-reflecting discourse by which he could stabilize (if not completely and finally gain) its particular dualistic worldview.

Abbreviations

Av Avestan

Buddh.Sogd Buddhist Sogdian

Gr Greek

Loc Locativ

Man.Sogd Manichaean Sogdian

MIndic Middle Indic

MMP Manichaean Middle Persian

MParth Manichaean Parthian

OAv Old Avestan

OI Old Indic

OIr Old Iranian

Pahl Pahlavi

PahlTr Pahlavi Translation

PahlV Pahlavi Vīdēvdād

PahlY Pahlavi Yasna

Pāz. Pāzand

Ved Vedic

YAv Young Avestan

ZMP Zoroastrian Middle Persian

AiW Altiranisches Wörterbuch

AWN Ardā Wirāz Nāmag

Bd Bundahišn

CHP Cīdag Handarz ī Pōryōtkēšān

Dd Dādestān ī dēnīg

Dk Dēnkard

FrW Fragments Westergaard

GrBd Greater Bundahišn

GW Gyān wifrās

IndBd Indian Bundahišn

MX Mēnōg ī Xrad

PahlV Pahlavi Vīdēvdād

PāzBd Pāzand Bundahišn

PT Pahlavi Texts

ŠGW Škand Gumānīg Wizār

WZ Wizīdagīhā ī Zādsparam

V Vīdēvdād

Vr Visparad

Y Yasna

Yt Yašt

Appendix I: Bd 1.1-1289

| GrBd | IndBd | |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | p̱ṯ’ ŠPYLdyn’ ʾwgwn pytʾk’90 <AYK> ʾwhrmzd bʾlystyk pṯ’ hlwsp ʾkʾsyh W wyhyh zmʾn’ y ʾknʾlk’ BYN lwšnyh hmʾy YHWWNt | cygwn MN dyn y mʾzdsnʾn ʾwg<w>n pytʾk AYK ʾwhrmzd bʾlystn’ pṯ’ hlwsp91 ʾkʾsyh W ŠPYLyh BYN lwšnyh xhmʾy92 bwt |

| pad weh-dēn ōwōn paydāg <kū> ohrmazd bālistīg pad harwisp-āgāhīh ud wehīh zamān ī akanārag andar rōšnīh hamē būd | ciyōn az dēn ī māzdēsnān ōwōn paydāg kū ohrmazd bālistan pad harwisp-āgāhīh ud wehīh andar rōšnīh xhamē būd93 | |

| In the Good Religion it is manifest: Ohrmazd was/is always on high, in omniscience and goodness <for> the Infinite Time in the light. | As it is manifest from the Mazdaean Religion: Ohrmazd was/is always on high, in omniscience and goodness in the light.94 | |

| 1.2 | ZK lwšnyh <W> gʾs W gyʾk y95 ʾwhrmzd [AYT’ MNW ʾsl lwšnyh YMLLWNyt’] W96 ZK hlwsp’ ʾkʾsyh W wyhyh97 zmʾn y ʾknʾlk’ cygwn ʾwhrmzd W gʾs98 W99 dyn W zmʾn’ y ʾwhrmzd YHWWNt’ HWʾnd100 | ZK lwšnyh gʾs W gyʾk y ʾwhrmzd [AYT’ MNW ʾsl lwšn’ YMRRWNd] W hlwsp’ ʾkʾsyh ŠPYLyh xnydʾmk101 y ʾwhrmzd [AYT MNW YMRRWNd102 dyn] [hm KRA 2 wcʾlšn’ ʾywk] ZK y xnydʾmk103 y zmʾn y ʾknʾlkʾwmnd cygwn ʾwhrmzd W gʾs W dyn W zmʾn’ ʾwhrmzd YHWWNt W AYT W hmʾy YHWWNyt104 |

| ān rōšnīh gāh ud gyāg ī Ohrmazd [ast kē asar rōšnīh gōwēd] ud ān harwisp-āgāhīh ud wehīh zamān ī akanārag ciyōn Ohrmazd ud gāh ud dēn ud zamān ī Ohrmazd būd hēnd | ān rōšnīh gāh ud gyāg ī Ohrmazd [ast kē asar rōšn gōwē(n)d] ud ān harwisp-āgāhīh ud wehīh xniyāmag ī Ohrmazd [ast kē gōwēd dēn] [ham harw dō wizārišn ēk] ān ī xniyāmag ī zamān ī akanāragōmand ciyōn Ohrmazd ud gāh ud dēn ud zamān <ī> Ohrmazd būd ud hast ud hamē bawēd | |

| That light is the time-space105 of Ohrmazd [there is one who says “Endless Light”], and that omniscience and goodness are <for> the Infinite Time, as Ohrmazd and the space and the Religion and the time of Ohrmazd are <always>. | That light is the time-space of Ohrmazd [there is one who says “Endless Light”], and that omniscience and goodness are the covering106 of Ohrmazd [there is one who says “the Religion” also]; [both interpretations are one (harwisp-āgāhīh ud wehīh = dēn)]; it is that covering which is for the Infinite Time, as Ohrmazd and the space and the Religion and the time of Ohrmazd were and are and will always be. | |

| 1.3 | ʾhlymn’ BYN tʾlykyh pṯ’ AHL dʾnšnyh W xztʾlkʾmkyh107 zwplpʾdk YHWWNt’ | ʾhlmn’ BYN tʾlykyh pṯ’ AHL dʾnš W ztʾlkʾmkyh W zwpʾy YHWWNt [W AYT MNW LA YHWWNyt] |

| Ahreman andar tārīgīh pad pas-dānišnīh ud zadār-kāmagīh zofr-pāyag būd | Ahreman andar tārīgīh pad pas-dāniš ud zadār-kāmagīh zofāy būd [ast kē nē bawēd]108 | |

| Ahreman was deep in the darkness, in after-knowledge and with the wish to kill. | Ahreman was deep in the darkness, in after-knowledge and with the wish to kill [there is one <who says>: he will not be <at the end>109]. | |

| 1.4 | APš ztʾl kʾmkyh xnydʾm110 W ZK tʾlykyh gywʾk’ [AYT’ xMNW111 ʾsl tʾlykyh YMRRWNyt112] | ZK ztʾlyh W hm ZK tʾlykyh gywʾk [AYT’ MNW ʾsl tʾlyk<yh> YMRRWNd] |

| u-š zadār-kāmagīh xniyām ud ān tārīgīh gyāg [ast kē asar tārīgīh gōwēd] | ud ān zadārīh ud ham ān tārīgīh gyāg [ast kē asar tārīg<īh> gōwēd]113 | |

| And the wish to kill is his covering114 and the darkness his space [there is one who say ‘the Endless Darkness’] | That killing and also that darkness are <his> space [there is one who says ‘the Endless Darkness’]. | |

| 1.5 | APšʾn mydʾn’ twhykyh YHWWN(y)t [AYT’ MNW wʾd] MNWš gwmycšn’ ptš | APšʾn mydʾn twhykyh bwt [AYT’ MNW wʾd YMRRWNd] MNW KWN gwmycšn y ptš115 |

| u-šān mayān tuhīgīh xbūd [ast kē Way] kē-š gumēzišn padiš | u-šān mayān tuhīgīh būd [ast kē Way gōwē(n)d] kē-š gumēzišn padiš | |

| And between them (“in their middle”) there was the void [there is one <who says> ‘Way]’, in which there is <then> the mixture.116 | And between them (“in their middle”) there was the void [there is one who says ‘Way]’, in which there is <then> the mixture.117 | |

| 1.6 | KRA 2 HWH̱nd knʾlkʾwmndyh y ʾknʾlkʾwmndyh | KRA 2 mynwd knʾlkʾwmnd W ʾknʾlkʾwmnd |

| har dō hēnd kanāragōmandīh ī akanāragōmandīh | harw dō mēnōy kanāragōmand ud akanāragōmand118 | |

| Both <spirits> exist as the finity of infinity. | Both <spirits> are finite and infinite. | |

| 1.7 | MH̱ bʾlystyh ZK y119 ʾsl lwšnyh120 YMLLWNyt’ [121AYK LA slʾwmnd]W zwpl pʾdk’ ZK y ʾsl tʾlykyh [W ZK AYT’ ʾknʾlyh122] | bʾlyst ZK y ʾsl lwšnyh YMRRWNd W zwpʾy ZK <y> ʾsl tʾlyk<yh> |

| cē bālistīh ān ī asar rōšnīh gōwēd [kū nē sarōmand] ud zofr-pāyag ān ī asar tārīgīh [ud ān ast akanārīh] | bālist ān ī asar rōšnīh gōwēnd ud zofāy-pāyag ān <ī> asar tārīg<īh>123 | |

| Because one calls the high ‚the Endless light’ [i.e., it is not bound], and the deep ‘the Endless Darkness’ [and that means ‘infinity’]. | The high one calls ‚the Endless light’, and the deep ‘the Endless Dark<ness>’. | |

| 1.8 | pṯ’ wymnd KRA 2 +knʾlkʾwmnd124 [AYK šʾn’ mydʾn’ twhykyh W125 ʾywk’ ʿL126 TWD LA ptwst’ HWH̱nd] | AYK šʾn mydʾn twhyk W ʾywk’ LWTH̱ TWD LA ptwst YKʿYMWNyt |

| ud pad wimand harw dō kanāragōmand [kū-šān mayān tuhīgīh ēk ō did nē paywast hēnd] | kū-šān mayān tuhīg ud ēk ō did nē paywast ēstēd127 | |

| And with regard to the boundary /at the boundary both <spirits> are finite [i.e., their middle is empty, and they are not connected one with the other] | i.e., their middle is empty, and they are not connected with each other. | |

| 1.9 | TWD KRA128 xdwʾn129 mynwd pṯ’ NPŠH̱130 tn’ knʾlk’ʾwmnd | W TWD KRA 2 mynwd pṯ’ NPŠH̱ tn’ knʾlkʾwmnd HWH̱nd |

| did harw xdōān mēnōy pad xwēš tan kanāragōmand | ud did harw dō mēnōy pad xwēš tan kanāragōmand hēnd131 | |

| Then again, both spirits <are> finite in themselves. | And then again, both spirits are finite in themselves. | |

| 1.10 | W132 TWD hlwsp ʾkʾsyh y ʾwhrmzd lʾd133KRA MH̱š BYN dʾnšn’ y ʾwhrmzd (.134) knʾlkʾwmnd MH̱ ZK y KRA 2 HWHnd ptmʾn YDʿYTW<N>(t)nd | W TWD hlwsp ʾkʾsyh <y> ʾwhrmzd lʾd KRA 2 MNDʿM BYN YHBWNšn’ (!) y ʾwhrmzd knʾlkʾwmnd W ʾknʾlkʾwmnd (!) MH̱ ZNH̱ ZK y BYN KRA 2ʾn mynwd135 ptmʾn YDʿYTWNnd |

| ud did harwisp-āgāhīh ī Ohrmazd rāy harw cē-š andar dānišn ī Ohrmazd kanāragōmand cē ān ī harw paymān dānēnd | ud did harwisp-āgāhīh <ī> Ohrmazd rāy harw dō ciš andar dāhišn (!) ī Ohrmazd kanāragōmand ud akanāragōmand cē ān ī andar harw dōān mēnōy paymān dānēnd136 | |

| And then again, on account of the omniscience of Ohrmazd, all what is in the knowledge of Ohrmazd is finite, for he knows the whole <timely limited> treaty. | And then again, on account of the omniscience of Ohrmazd, the both two things (gētīy and mēnōy?) in the creation of Ohrmazd are finite and infinite, for he knows the <timely limited> treaty between the two spirits. | |

| 1.11 | W TWD bwndk pʾthšʾyh137 y dʾm y138 ʾwhrmzd pṯ’ tn’ y psyn’ ʿD139 hmʾy hmʾy lwbšnyh W ZK AYT’ ʾknʾlkyh | W TWD bwndk W (!) pʾtšʾhyh xy140 dʾm y ʾwhrmzd pṯ’ tn’ <y> psyn YHWWNyt (!) W ZKp141 AYT y ʿD hmʾk hmʾk lwbšnyh ʾknʾlkʾwmnd |

| ud did bowandag-pādaxšāyīh ī dām ī Ohrmazd pad tan ī pasēn tā hamē ud hamē-rawišnīh [ud ān ast akanāragīh] | ud did bowandag-pādaxšāyīh ī dām ī Ohrmazd pad tan <ī> pasēn bawēd ud ān-iz ast tā hamē ud hamē-rawišnīh [akanāragōmand142] | |

| And then again, the perfect sovereignty143 of the creatures of Ohrmazd at <the time of> the Final Body <will be> for eternity [and that means ‘infinity’] | And then again, the perfect sovereignty of the creatures of Ohrmazd at <the time of> the Final Body will be that that is for [infinite] eternity | |

| 1.12 | dʾm y144 ʾhlymn pṯ’ ZK zmʾn’ BRA ʾpsyhynnd ʿD145 y AMT tn’ y psyn’ YHWWNyt’146 ZKc AYT’ knʾlkʾwmndyh | W dʾm y ʾhlmn pṯ’ ZK zmʾn BRA ʾpsynyt MNW tn’ psyn’ YHWWNyt ZKp AYT ʾknʾlkyh (!) |

| ud dām ī Ahreman pad ān zamān be abesīhēnēd tā ī ka tan ī pasēn bawēd [ān-iz ast kanāragōmandīh] | ud dām ī Ahreman pad ān zamān be abesī<hē>nēd kē tan ī pasēn bawēd [ān-iz ast akanāragīh147] | |

| And the creatures of Ahreman will be destroyed at that time, so that the Final Body can be [also that means ‘finity’ (sic!)]. | And the creatures of Ahreman will be destroyed at that time, so that the Final Body can be [also that means ‘infinity’ (sic!)]. |

Appendix II: The dualistic schools in Iran according to Šahrastānī

Majūs

| Schools that teach the existence of two principles: | light (infinite) | darkness (finite) | further teachings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kayūmarthīya | = infinite Yazdān | = finite Ahriman | Ahriman is from a thought of Yazdān |

| Zarwānīya | = Hurmuz; light | Ahriman, who is in the darkness (= underworld, „ohne Grenze und Ende“148) | Ahriman is from a doubt / a nihilistic thought of Zarwān (Zarwān < light) |

| Zarāduštīya | existence of Yazdān + light | existence of Ahriman + darkness | all existing: a) is created from light + darkness (as a mixture of light and darkness); b) light + darkness (Yazdān + Ahriman) are “der Anfang der geschaffenen Dinge der Welt”149) |

| Yazdān creates light and darkness | = Ahriman? |

Thanawīya

| Schools that teach the existence of two eternal principles: | light (infinite) | darkness (infinite) | further teachings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mānawīya | is with perception | is with perception | two kinds of mixture: I) intentional; II) accidental |

| Mazdakīya | is with intention and free choice | is without intention and by chance | |

| Daifzānīya | cf. Mazdakīya | cf. Mazdakīya | |

| Markūnīya | light | darkness | existence of a connector (cause of mixing) |

| Kainawīya; Sziyāmīya; Tanāsuchīya | fire | water | earth is in the middle |

References

Agathias. 1975. The Histories: Translated with an Introduction and Short Explanatory Notes. Translated by Joseph D. Frendo. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Anquetil-Duperron, Abraham Hyacinthe. 1771. Zend-Avesta: Ouvrage de Zoroastre I-II. Paris: Tilliard.

Burkert, Walter. 1963. “Iranisches bei Anaximandros.” Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 106: 97–134.

Cantera, Alberto. 1999. “Die Stellung der Sprache der Pahlavi-Übersetzung des Avesta innerhalb des Mittelpersischen.” Studia Iranica 28: 173–204.

———. 2004. Studien zur Pahlavi-Übersetzung des Avesta. Iranica, Band 7. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Cereti, Carlo G., and David N. MacKenzie. 2003. “Except the Battle: Zoroastrian Cosmogony in the 1st Chapter of the Greater Bundahišn.” In Religious Themes and Texts in Pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia: Studies in Honour of Professor Gherardo Gnoli on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday on 6th December 2002, edited by Carlo G. Cereti, Mauro Maggi, and Elio Provasi, 31–60. Beiträge Zur Iranistik 24. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

Colditz, Iris. 2005. “Zur Adaption zoroastrischer Terminologie in Manis Šābuhragān.” In Languages of Iran: Past and Present; Iranian Studies in Memoriam David Neil MacKenzie, edited by Dieter Weber, 17–26. Iranica, Band 8. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Gharib, Badresaman. 1995. Sogdian Dictionary: Sogdian - Persian - English. Tehran: Farhangan Publications.

Gignoux, Philippe. 2003. “Zamān ou le Temps Philosophique dans le Dēnkard III.” In Religious Themes and Texts in Pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia: Studies in Honour of Professor Gherardo Gnoli on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday on 6th December 2002, edited by Carlo G. Cereti, Mauro Maggi, and Elio Provasi, 115–22. Beiträge zur Iranistik 24. Wiesbaden: Reichelt Verlag.

Gnoli, Gherardo. 1974. “Politique Religieuse sous les Achémenides.” In Commemoration Cyrus: Actes du Congrès de Shiraz 1971 et autres etudes redigees a l’occasion du 2500e anniversaire de la fondation de l’empire perse; Hommage universel, edited by Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin, II:117–90. Acta Iranica 2.

———. 1995. “Einige Bemerkungen zum Altiranischen Dualismus.” In Proceedings of the Second European Conference of Iranian Studies: Held in Bamberg, 30th September to 4th October 1991, by the Societas Iranologica Europaea, edited by Bernhard Fragner, Christa Fragner, Gherardo Gnoli, Roxane Haag-Higuchi, Mauro Maggi, and Paola Orsatti, 213–27. Rome: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

Gonda, Jan. 1963. The Vision of the Vedic Poets. The Hague: Mouton & Co.

Haarbrücker, Theodor, ed. 1850–1851. Abu-“l-Fath” Muh’ammad asch-Schahrastâni’s Religionspartheien und Philosophen-Schulen. Halle: C. A. Schwetschke und Sohn.

Hegel, Georg W.Fr. 1970. Vorlesungen über Die Ästhetik I-III. Edited by Eva Moldenhauer and Karl Markus Michel. Frankfurt/Main: Surhkamp.

———. 1986a. Vorlesungen über Die Geschichte Der Philosophie I-II. Edited by Eva Moldenhauer and Karl Markus Michel. Frankfurt/Main: Surhkamp.

———. 1986b. Vorlesungen über Die Philosophie Der Religion I-III. Edited by Eva Moldenhauer and Karl Markus Michel. Frankfurt/Main: Surhkamp.

———. 1986c. Vorlesungen über Die Philosophie Der Weltgeschichte. Edited by Eva Moldenhauer and Karl Markus Michel. Frankfurt/Main: Surhkamp.

Henning, Walter Bruno. 1948. “A Sogdian Fragment of the Manichaean Cosmogony.” BSO(A)S 12: 306–18.

Herder, Johann Gottfried. 1775. Erläuterungen Zum Neuen Testament Aus Einer Neueröffneten Morgenländischen Quelle. Riga.

Hicks, Robert D. (1925) 1972. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Diogenes Laertius. Cambridge.

Hoffmann, Karl, and Bernhard Forssman. 1996. Avestische Laut- und Flexionslehre. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, Band 84. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

Humbach, Helmut. 1991. The Gāthās of Zarathushtra: And the Other Old Avestan Texts. 2 vols. Heidelberg: C. Winter.

Hutter, Manfred. 1992. Manis Kosmogonische Šābuhragān-Texte. Edition, Kommentar Und Literaturgeschichtliche Einordnung Der Manichäisch-Mittelpersischen Handschriften M 98/99 I Und M 7980–7984. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Jong, Albert de. 1997. Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature. Leiden: Brill.

Kellens, Jean. 1998. “Considérations sur l’histoire de l’Avesta.” JA 286: 451–519.

———. 2015. “The Gāthās, Said to Be of Zarathustra.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism, edited by Michael Stausberg and Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina, 44–50. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Kleuker, Johann Friedrich. 1777–1786. Zend-Avesta, Zoroasters Lebendiges Wort, Worin Die Lehren Und Meinungen Dieses Gesezgebers von Gott, Welt, Natur, Menschen; Ingleichen Die Ceremonien Des Heiligen Dienstes Der Parsen U.s.f. Aufbehalten Sind. Erster Theil, Welcher Mit Dem, Was Vorausgeht, Die Beiden Bücher Jzeschne Und Vispered Enthält. Nach Dem Französischen Des Herrn Anquetil Du Perron (Zweite Durch Und Durch Verbesserte Und Vermehrte Ausgabe). Zweither Theil, Der, Außer Einigen Abhandlungen, Die übrigen Zendbücher, Jschts Sades, Si-Ruze Und Vendidad Enthält. Dritter Und Letzter Theil, Welcher Zoroasters Leben, Den Bun-Dehesch, Zwei Kleine Wörterbücher, Und Die Bürgerlichen Und Gottesdienstlichen Gebräuche Bei Den Jetzigen Parsen Enthält. Nach Dem Französischen Des Herrn Anquetil. Riga.

König, Götz. 2010. Geschlechtsmoral und Gleichgeschlechtlichkeit im Zoroastrismus. Iranica, Band 18. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

———. 2020. “Studies on the History of Rationality in Ancient Iran III: Philosophy of Nature.” In Festschrift Kreyenbroek, 219–38.

Lanfranchi, Giovanni-Battista. 2001. “La volta celeste nelle speculazioni cosmografiche di età neo-assira.” In L’uomo antico e il cosmo: 3. Convegno internazionale di archeologia e astronomia, Roma, 15-16 maggio 2000, edited by Accademia nazionale dei Lincei, 149–62. Atti dei convegni lincei 171. Rome: Accademia nazionale dei Lincei.

Menasce, Jean de. 1945. Une apologétique mazdéenne du 9. siecle: Škand-Gumānīk vičār; La solution décisive des doutes; Texte pazend-pehlevi transcrit, traduit et commenté. Fribourg-en-Suisse: Librairie de l’Université.

———, ed. 1973. Le troisième livre du Denkart: Traduit du pehlevi. Paris: Klincksieck.

Panaino, Antonio. 1995. “Uranographia Iranica I: The Three Heavens in the Zoroastrian Tradition and the Mesopotamian Background.” In Au carrefour des religions: Hommage à Philippe Gignoux, edited by Rika Gyselen, 205–25. Leuven: Peeters.

———. 2001. “A Few Remarks on the Zoroastrian Conception of the Status of Aŋra Mainyu and of the Daēvas.” In Démons et merveilles d’orient, edited by Rika Gyselen, 99–108. Res Orientales 13. Bures-sur-Yvette: Peeters.

Plutarch. 1889. Moralia. Edited by Gregorius N. Bernardakis. Leipzig: Teubner.

———. 1936. Moralia: With an Englisch Translation. Edited by Frank Cole Babbitt. Vol. 5. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schmidt, Hans-Peter. 1996. “Ahreman and the Mixture (gumezisn) of Good and Evil.” In K.R. Cama Oriental Institute: Second International Congress Proceedings (5th to 8th January 1995), edited by Hormazdiar J. M. Desai and Homai N. Modi, 79–96. Bombay: The K.R. Cama Oriental Institute.

Shaki, Mansour. 1970. “Some Basic Tenets of the Eclectic Metaphysics of the Dēnkart.” Archív Orientální 38: 277–312.

———. 1973. “A Few Philosophical and Cosmological Chapters of the Denkart.” Archív Orientální 38: 133–64.

———. 1975. “Two Middle Persian Philosophical Terms LYSTKʾ and MʾTKʾ.” In Iran ancien: Actes du XXIXe Congrès international, edited by Philippe Gignoux, 52–57. Paris: L’Asiathèque.

———. 1998. “Elements.” In Encyclopædia Iranica, 8:357–60. London, UK: Routledge.

Solmsen, Friedrich. 1962. “Anaximander’s Infinite: Traces and Influences.” Archiv für Geschichte und Philosophie 44: 109–31.

Sundermann, Werner. 1982. “Soziale Typenbegriffe altgriechischen Ursprungs in der altiranischen Überlieferung.” In Soziale Typenbegriffe im alten Griechenland, edited by Elisabeth Charlotte Welskopf, VII:14–38. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

———. 1986. “Studien zur kirchengeschichtlichen Literatur der iranischen Manichäer I.” Altorientalische Forschungen 13: 42–92.

Taillieu, Dieter. 2003. “Pazand Nišāmī Between Light and Darkness.” In Iranica Selecta: Studies in Honour of Professor Wojciech Skalmowski on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday, edited by Alois Van Tongerloo, 8:239–46. Silk Road Studies. Turnhout: Brepols. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.SRS-EB.5.112516.

West, Edward William. 1880. Pahlavi Texts. Part I: The Bundahis-Bahman Yast, and Shāyast Lā-Shāyast. Oxford.

Agathias’ information is based on “the testimony of Berosus of Babylon, Athenocles and Simacus who recorded the ancient history of the Assyrians and Medes” (Agathias, Hist., 2.24.8).↩︎

For -dn- > -(n)n- cf. OAv/YAv xvaēna- < *hvaidna- (see Hoffmann and Forssman 1996, 97).↩︎

See the quotations in AiW 968–969.↩︎

PahlTr ō bun ī axwān ī tom kē ērang dūzax [abāz ham-ō-ham dūd] “to the basis of the dark places of being, the horrible hell [back to the clumping smoke].” For darkness as a characteristic of hell, see especially and already the accumulation of the word “dark” (təma-) in V 5.62, 18.76: təmaŋhaēnə. təmasciϑrəm. təmaŋhəm. → PahlTr tom-arzānīgān … tom-tōhmagān … tom. In later sources, hell is described as a place where darkness is nearly material; see MX 7.30f., AWN 18, PahlV 5.62 (see König 2010, 338–39).↩︎

The term for hiding the daēuuas in the earth is YAv zəmarə-guz- (Y 9.15, Yt 19.81; FrW 4.3; s. AiW 1665–1666).↩︎

See Dd 0.23.↩︎

For a reconstruction of the process of the Avestan text production, see Kellens (1998, 488–516).↩︎

The most important sources are the Pahlavi translations of the Avesta and their (late Sasanian/early Islamic?) commentaries. Indirect sources are the Manichaean texts.↩︎

Lived around 390 and 340 BCE in Knidos.↩︎

Born 378/377 BCE in Chios; died between 323 and 300 BCE, probably in Alexandria.↩︎

Lived in the third century BCE (*289/277 BCE, †208/204 BCE).↩︎

Or “two realms”?↩︎

In Plutarch’s (around 45–125 AD) de Iside 46 ϑεός, “god” is used as a general term for two highest divinities (θεοὺς), which are seen as “rivals” (ἀντιτέχνους); referring to the Persian terminology, Plutarch makes the distinction between ϑεός = Ahura Mazdā (Ὡρομάζης) and δαίμων Aŋra Mainiiu (Ἀρειμάνιος). This distinction ϑεός / δαίμων is probably an allusion to Av ahura / daēuua.↩︎

See, 900 years later, the conceptualisation of Ὀρμισδάτης (< *Ohrmizd-dād [?]) and Ἀριμάνης as δύο τὰς πρώτας ἀρχάς in Agathias (536–582 AD), Hist. 2-24ff. For δύο τὰς πρώτας, see the expression “the two spirits in the earliness (of being)” (see Y 30.3 tā. mainiiū. pauruiiē.; Y 45.2 aŋhə̄uš. mainiiū. pauruiiē.), which the PahlTr glosses with Ohrmazd ud Gannāg. It seems that the Avestan expression was later simplified to “the two first spirits”; see PahlY 30.3 har 2 mēnōg […] ā-šān fradom; Y 45.2 andar axwān mēnōgīgīh fradom [dahišnīgīh]).↩︎

The similarity of Anaximander’s and the Iranian model of the light-sphere is still unrecognized in Solmsen (1962), an article on “traces and influences” of and on Anaximander’s Infinite. For a Mesopotamian background of this model, see Panaino (1995) and Lanfranchi (2001, 161–62).↩︎

See the fragments M475, M477, M482, M472; on the title dw bwn in the Parthian translation, see Sundermann (1986, 84, n. 182); see also the Old Turkic Iki Yiltiz Nom, chin. Erh-tsung ching “book of the two principles” (MIK III 198 [T II D 171]), and the Chinese phrase (see Hutter 1992, 146 and Reck “Šābuhragān” in Encyclopædia Iranica: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sabuhragan).↩︎

See, e.g., ŠGW 11.342 əž. bun. aṇdā. faržąm. “from the beginning to the end”; ŠGW 12.51 u. bun. u. miiąn. u. faržąm. “beginning, middle, end.”↩︎

ŠGW sometimes uses bun in the sense of “principle” (more common buniištaa.), see ŠGW 11.85 (?), 11.95; see also ŠGW 11.254 bun. Buniiašt.↩︎

An adjective with the meaning “fundamental” can be found in GrBd 1.52b u-š nazdist Amahrspand dād 6 bun “he created first the Amahraspand, the six fundamental one”; GrBd 26.129 Ohrmazd ud ān 6 Amahrspand ī bun “Ohrmazd and the six fundamental Amahraspands.”↩︎

Beyond the passage PahlV 19.47, the word bun is used only in the glosses of this work, where bun (and also bunīh) appears in idiomatic phrases (ō bun [in the context of sin/merit]; bun ud bar [see here also PahlV 3.25]). The philosophical meaning “principle” seems to be absent in all instances (and is perhaps only indirectly reflected in a-bun “not principally” [adjective to sag, gurg in PahlV 13.42, 43]).↩︎

Because we have seen that Gr ἀρχή probably translates as OIr *buna- “principle,” we cannot assume that the canonized translation/commentary of the Pahlavi Vīdēvdād was fixed in a period before a ‘philosophical’ meaning of bun entered the ZMP literature.↩︎

All translations by the author unless noted otherwise.↩︎

The term dād ī stōd might be connected with the Nask Stōt/Stōd, the Nask which is the first or last of the 21 Nasks of the Sasanian Avesta, and which incorporated the OAv texts (on the Staotas Yesniias see Kellens 1998, 496–500).↩︎

The name Parthian nsg jywʾng (MP *nsk zy(w)ndk’) remains an enigma, since such a Nask is not part of the Nask-Avesta (the Sasanian/Great Avesta). Firstly, the name evokes the expression nibegān zīndagān “Living Books,” used by Mani (in M 5494 [a fragment probably belonging to the Šabuhragān]) with regard to his own works (see the designation of the εὐαγγέλιον also as “Living Gospel” or “Gospel of the Living”; see also the designation of the text “Opening of the doors,” one of the Manichaean canonical scripture, as “the Treasure of the living”; the Greek and Latin name of Mani, Μανιχαιος/Manichaeus, is from Syriac Mâníḥayyâ “the living Mani”). Secondly, there is a similarity to a term used in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, “Zend-Avesta,” which was understood as “Living Avesta” by the first European Iranologists; see already the introduction of Herder’s Erläuterungen zum Neuen Testament aus einer neueröffneten morgenländischen Quelle, published 1775 (Herder 1775), and J. Fr. Kleuker Zend-Avesta. Zoroasters Lebendiges Wort (Kleuker 1777–1786). Herder/Kleuker probably picked up an old folk etymology of zend as zende (zindeh < zīndag) (the source of which is still unknown, but it seems that it was not Anquetil who established such an understanding of “Zand”). This is indicated by the well-known passage Dk 5.24.13, according to which zīndag-gōwišnīg saxwan “the living speech” is held in higher esteem than ān ī pad nibišt “what is written” (see Dk 5.24.13), probably because of the fact that the zīndag-gōwišnīg saxwan was composed in the Avestan language, but the written text is in Pahlavi.↩︎

The source of this translation is Anquetil (1771, II:423–424).↩︎

It is still a matter of debate whether this asymmetrical ontological conception of Ohrmazd and Ahreman has its origin in the Avesta (see Gnoli 1995; Schmidt 1996; Panaino 2001).↩︎

For the two epistemological-ontological categories in the Pahlavi writings (“what can be seen” and “what can be touched”), see already Herakcitus (in Hippolytos, Haer. IX 9,6 (DK 22 B 56)).↩︎

In the sense of the German nominalized adjective ‘das Gute.’↩︎

Later Zoroastrianism develops or strengthens the principle of xwēškārīh and kunišn, the active fulfilment of one’s own duty (according to one’s own ability). This principle is a bastion against thoughts of world-negation and against fatalism. Šahrastānī says about the Zarāduštīya that this Mazdaean school not only knows a Mīnū-Gītī-dualism, but “was in der Welt ist, in zwei Theile getheilt, Bachschisch (baxšiš) (Gnade) und Kunisch (kuniš) (Thätigkeit) worunter er (Zardušt [GK]) die Anordnung (Gottes) und das Thun (des Menschen) versteht, und ein Jeder sei in Beziehung auf das Zweite vorherbestimmt” (Haarbrücker 1850–1851, I:283: “What is in the world is divided into two parts, Bachschisch (baxšiš) (grace) and Kunisch (kuniš) (deeds), which he (Zardušt [GK]) understands as the order (of God) and the actions (of man), and everyone is predestined for the latter”). See the opposition mentioned in Dd 70.3 pad brēhēnišn … pad kunišn, cf. B 325.7 (Dk 4.34) baxt-išān abar ān ī brēhēnīdārīh pad kunišn (“their fate <is fulfilled> with regard to creation by action”). On the dialectic of fate and action see König (2010, 79, 82).↩︎

Ādurbād’s use of a past tense form būd—see Mānī‘s counter-position in Dk 3.200.7 with the hint to a creation demon—seems to point to a created infinity (see the position in Plato’s Timaios and the position of Philon and Augustin; Aristotle, however, argues against the assumption of a created infinity, see fn. 33).↩︎

Text in B dgy; DkS 5.241 dgl (Menasce 1945, 231, 1973, 208 reads dīg “hier”).↩︎

According to the opposition of the two epithets of zruuan- in the Younger Avesta, darəγō.xvaδāta- and akarana- (see Ny 1.8; Y 72.10; V 19.13), the “long” time—according to AiW 696 the meaning of darəγō.xvaδāta- is also “ewig”—differs from the “infinite” (akarana-) time (see Menasce 1945, 231–32).↩︎

Sundermann (1982, 32–33), where a transcription and translation of the chapter is given, points to Aristotle’s “Sophistische Widerlegungen” (περὶ σοφιστικῶν ἐλέγχων), chapter 5, which discusses the assumption of a world without a beginning. The σοφιστικῶν ἐλέγχων were of great importance for the knowledge of Greek philosophical teachings in the Middle East: “Kein anderes Werk der griechischen Literatur, das vornehmlich den Sophisten und ihrem Wirken gewidmet ist, scheint im nahöstlichen Schrifttum der frühislamischen Zeit ähnliche Verbreitung gefunden zu haben wie die Sophistici Elenchi” (Sundermann 1982, 23: “No other work of Greek literature dedicated principally to the Sophists and their deeds seems to have been disseminated as widely in Middle Eastern writing of early Islamic time as the Sophistici Elenchi”).↩︎

De Menasce (1945, 234) explains: “les abūn sont les ἀγεννητοι, αὐτοϕυεĩς des écrits grecs sur le manichéisme et sur le dualism en general” (“the abūn are the ἀγεννητοι, αὐτοϕυεĩς of the Greek writings on Manichaeism and on dualism in general”).↩︎

For a-bun, see also Dk 3.126, Dk 3.127, Dk 3.109 (a-bunīh). In Dk 3.109 a-bunīh seems to have the opposite meaning of bunīh; see ŠGW 11.247, 250 abuniiašt. “the one (spirit) who is not a principle.”↩︎

An alternative reading would be a-sāmān “unlimited” (pad tan a-sāmān “material-infinite”), a word used in the ŠGW. For a reading tan-āsamān, see the passage ŠGW 16.8-20, where the sky appears as Āharman’s first creation, made from the “skin” (pōst) of the Kunī. də̄β., the (probably male) “general of Āharman” (spāhsalār. i. Āharman.).↩︎

Translation uncertain.↩︎

See the notice in the polemical chapter 16 of the ŠGW: bun. gaβəšni. i. Mānāe. aβar. akanāraī. i. buniiaštagą. “the original writings of Mānāe are on the infinity of the <two> principles” (ŠGW 16.4).↩︎

According to ŠGW 5.40, the notion “substance” (gōhr) implies the notion “origin” (bun) (gōhr ciš ī nē bun “substance without origin <is a meaningless notion>”). This definition leads to the conclusion that something a-bun is a thing without substance.↩︎

See Appendix II.↩︎

Within the Thanawīya, there are different opinions about 1) the nature of light and darkness and 2) the separation of light from darkness.↩︎

Dk 3 presents the discussions between Mānī (Dk 3.200) and Ādurbād (Dk 3.199), Mazdag (“Gurgīh”) (Dk 3.202) and Xosrō I (Dk 3.201) inversely, historically.↩︎

The case of the spiritual (mēnōg) is therefore a problem, because Ohrmazd and Ahreman (goodness and Evil) have a mēnōg-existence.↩︎

According to Hegel (see the chapters or notes on the Persian religion in Hegel 1986a, 1986b, 1986c, 1970), the characteristic of the “Persian” (= Zoroastrian) religion is the coincidence of a natural phenomenon (“light”) with a concept (“goodness”).↩︎

The word bun-dahišn(īh) is translated by West (1880, xxii), as “’creation of the beginning’, or ‘original creation’”. As we can see from GrBd 1.0 (pas abar ciyōnīh ī gēhān dām az bundahišnīh tā frazām) or GrBd 24e22 (pad bundahišn … pad fraškerd), bundahišn(īh) refers to the first period of being. However, Dk 3.284 indicates a slightly different meaning of the word, see B 224.1-2: zamān dahišnān bun Ohrmazd hamēyīgīh “time is the fundament of creation, is the eternity of Ohrmazd.” According to this interpretation, bun-dahišn refers to time in the sense of an ontological fundament.↩︎

As the Gāϑās claim that Ahura Mazdā is the father of the evil spirit, the Kayūmarthīya teaches that Ahriman came into being from a thought of Yazdān, and the Zarwānīya say that Ahriman emerged from doubt or a nihilistic thought of Zarwān, the question of a monistic origin of the Zoroastrian dualism returns even in the Pahlavi literature that seems to belong to the Zarāduštīya, the Zoroastrian school which taught two sharply separated principles. In WD 8, the question is asked: Gannāg Mēnōy druwand […] pad bundahišn dām Ohrmazd ast “Is the deceitful Gannāg Mēnōy […] in the bundahišn-period a creature of Ohrmazd?”, a question that is positively answered. It is further stated that this creation of evil from goodness was necessary for a punishment of the ruwānān druwandān “deceitful souls” in “hell”.↩︎

As is shown by the metonymical usage in CHP 12, the verbal roots dā- “to set; to give” / murnj-ēn- (Av marək-, mərəṇca-) “to destroy” signify the most typical actions of Ohrmazd and Ahreman. In ŠGW the principles are referred to as “(origin of) truth” and “lie”; see ŠGW 11.383 bun. du. yak. kə. rāstī. ažaš. yak. kə. drōžanī. “there are two principles: one from which is truth, one which is the lie.”↩︎

According to* Šahrastānī, the Majuš consider only the creator as an (a-)bun.↩︎

See Appendix I.↩︎

The GrBd seems to pick up elements from the Kayūmarthīya (Gayōmard is the light-being [see GrBd 7], not Zardušt (as in the Zarāduštīya, see Haarbrücker 1850–1851, I:281); Zardušt’s legend is—in contrast to the WZ—missing in the Bundahišn), but also from the Zarāduštīya (accentuation of the mixing of the elements [only the GrBd refers to the Aristotelian theory of elements]).↩︎

A long discussion on the problem of infinity can be found (as a critique of Manichaeism) in ŠGW 16.66-111 (text incomplete). Mardānfarrox says that God is unlimited because he cannot be encompassed by understanding (dānašni.) (ŠGW 16.66). There is a strange resemblance of Bd 1.1-12 and the structure of ŠGW 16, a Zoroastrian description and critique of Manichaean teachings. ŠGW starts with an account on the Manichaean cosmogony. After a brief note on the border of the two principles, the discussion on finitude/infinity starts (see Bd 1.3-4 on Ahreman, 1.5 on the border, 1.6-12 on finitude/infinity).↩︎

This is quite likely, since it is hardly possible that IndBd descended from GrBd, or that GrBd descended from IndBd.↩︎

According to ŠGW 5.41 the notion of “struggle” implies the notion of “finitude” (u. kōxšišn ī nē kanāragōmandīh” “struggle that has no end <is an impossible thing>”). It is therefore clear that the discussion in Bd 1.1-12 on finitude/infinity is deeply connected with the idea of a ‘pact’ of the two principles.↩︎

The interpolation in GrBd and the gloss in IndBd correspond with each other. Both additions change a symmetrical picture of Ohrmazd and Ahreman into an asymmetrical one (Ohrmazd is infinite, Ahreman is ultimately finite).↩︎

Most interesting in this regard is the proposition in Bd 1.6 that both principles are kanāragōmandīh ī/ud akanāragōmandīh “finitude of/and infinity,” the idea behind which could be that ‘two infinities’ produce a “border” (wimand, see Bd 1.7; cf. ŠGW 16.51), from which again finitude is produced.↩︎

See PahlTr Yt 1.1 u-š ohrmazdīh radīh ud xwadāyīh u-š dādārīh dām-dahišnīh u-š abzōnīgīh ēd kū-š az ciš-ē was ciš tuwān abzūd ohrmazd gāh ud dēn ud zamān hamē būd ud hamē ast az ān gyāg paydāg misuuānahe. gātuuō. xvaδātahe. mēšag sūd gāh ī ohrmazddād “and his ‘Ohrmazd-being’ <means> Ratu-being and reign; and his ‘creatorship’ <means> creation of the creature; and his ‘prosperity’ <means>: he is able to produce many things from one <thing>. Ohrmazd existed always as (?) the space and the Religion and the time, and he will always exist; this is meant by the words misuuānahe. gātuuō. xvaδātahe. → mēšag sūd gāh ī ohrmazddād”.↩︎

While an-aǧra- (AiW 114f.) is always combined with “lights,” a-karana- (AiW 46) is nearly always a predicate of time (zruun-) or space (cf. karana- AiW 451). According to two predicates used in Yt 8.48, the sti of God seems qualified by the infinity/endlessness of lights, time, and space.↩︎

On the adoption of Neoplatonic elements, see Shaki (1970, 1973).↩︎

Gonda (1963, 267) spoke of “the four hypostases of the one God” (namely: “Ohrmazd himself and his Space, Religion and Time”).↩︎

Dk 3.483 is entitled abar dō buništ (Dk 3.483) “On the two principles” (the text uses dō buništ besides dō bun). These two principles for the kār ī mardōm (which could be kerbag ayāb wināh) are xrad/Wahman and waran/Akōman. Dk 3.119 deals with the dō-buništagīh/dō-bun and its relation to the transformation of things, i.e., with the relation to element theory. In Dk 3.414 “generosity” (rādīh), which is “warm” (garm), and “avarice” (penīh), which is “cold” (sard), are called the dō bun ast pad mardōm axw “the two fundamental principles of human being”. In Dk 3.40, the term dō buništag (the dō buništag ī hamēyīg) is (polemically) applied to the Christian concept of the Father and the Son. Nearly every chapter of Dk 3 follows a dualistic structure. The author presents first a concept according to its true (= Zoroastrian), then according to its wrong meaning. The book of Ādurfarrbay’s pupil Mardānfarrox is then an apologia of dualism and a refutation of Manichaeism and of non-dualistic positions. ŠGW has many instances of expressions such as du. buniiaštaa. and the like.↩︎

See GrBd 3.7 ātaš kē brāh az asar rōšn gāh ī Ohrmazd.↩︎

See, for the “1000 chapters,” Dk 8.20-21 (B 528.8-13; DkM 679.15-20) Zarduxšt cāšišn andar Ērān-šahr hazār būd “from the teaching (cāšišn) of Zarduxšt 1000 <parts> existed in Ērān-šahr”.↩︎

For further “chains of light,” see Dk 4.40 (B 326.7-8); Dk 3.267 (B 215.15-18).↩︎

Menasce (1973) reads rās. The word occurs frequently in the cosmological chapters Dk 3.73, 123, 192, 263, 365, 371, 380, 382.↩︎

On zahāg and related terms, see especially Shaki (1975, 1998).↩︎

GrBd 1.54; 1a6-13, 1a16-21. For the IndBd cf. IndBd 6-10 (= GrBd 6, but only the sequence until the ox).↩︎

GrBd1a4; GrBd 3.7-9; GrBd 6/WZ 3; WZ 1.25.↩︎

Cf. GrBd 7.9 (TD2 73.3-11; TD1 59.15ff.; DH 38.5ff.). Cf. V 11.↩︎

The extraordinary position of fire is alluded to already in Yt 13. However, the construction gives the impression that Aristotle’s division of the world into a sublunary and lunar part, i.e., into the four elements and the Quinta Essentia, has had an impact on the Bundahišn.↩︎

According to GrBd 18 (IndBd 17), the transcendent (mēnōg) aspect of fire is the xwarrah (Av xvarənah).↩︎

The system of correspondences is, I guess, an extension of the old correspondence of cow/ox and moon (Yt 7).↩︎

Light and dark seem to enter a position in the theory of the four elements which (Western) Iran seemingly adopted from Greece; it is a tricky problem to decide whether a) the pre-Aristotelian Greek elements theory always had a dualistic aspect, b) this dualistic aspect is related to the Iranian dualism, and c) Iran [Western Iran] was familiar with the four elements in and before the fifth century BCE already [see Her. 1.131]). In some texts of the Pahlavi literature, we recognize that the mythical Ahremanic pollution of the materia (see GrBd 6), the “mixture” (gumēzišn), is reformulated with the help of the (so-called) ‘Greek’ elements theory. The materia appears in two extreme basic formations (garm-xwēd; sard-hušk). The ‘history of nature’ is the mixing (āmēzišn) of the basic elements and their qualities. Only the extreme and pure basic formations can be identified with light and darkness, see, e.g., Dk 3.105 (with reference to the mēnōg-field), B 73.2f. ud rōšn mēnōg pad garm-xwēd nērōg zīndag-cihrīh …, B 73.4f. ud tār mēnōg marg-gōhr sard-hušk …. Thus, the scheme is: rōšn „light“ : tār „darkness“ = garm-xwēd „warm-moist“ : sard-hušk “cold-dry.”↩︎

de Jong (1997, 170–71), however, has noted the similarity of de Iside 46 and the beginning of the Bundahišn, and he speculates that this is “due to a use Plutarch could make of a source which transmitted a version of the Zoroastrian cosmogony very much like the one preserved in the Bundahišn.”" Concerning de Iside 47, de Jong (1997, 184–204, see especially pp. 199-204 for eschatological parallels), gives some hints to the Bundahišn and the Wizīdagīhā ī Zādsparam, but, according to him, “Chapter 47 of De Iside is not a structured chronological story” (1997, 190, cf. p. 184).↩︎

A few Old Avestan phrases used for light entities are decontextualized and recontextualized in the Younger Avesta, see, e.g., (Ahura Mazdā’s) “lights” (raocā̊.) in the formula raocə̄bīš. rōiϑβən. xvāϑrā. (Y 12.1 < Y 31.7) (“Let the comforts (displayed) intersperse with light”; Humbach 1991, I:137).↩︎

See Šahrastānī (Haarbrücker 1850–1851, I:282): “Gott aber sei der Schöpfer des Lichtes und der Finsternis” (“God be the creator of light and darkness”).↩︎

See Gr αἰών. With darəga- āiiū- cf. OI dīrghā́yu-.↩︎

For the designation of the evil darkness, the təmah-words are more frequent used than the tąϑra-words (tąϑra- n. [used in plural] in V 7.79, N 68; tąϑrō.cinah- “who searches for the dark” V 13.47 (perhaps as opposite of aṣ̌a.cinah- “who searches for aṣ̌a”); tąϑriia- “dark” in Yt 14.13, 14.31, 16.10, 11.4; Tąϑriiăuuaṇt- EN Yt 5.109, Yt 9.31.*↩︎

Man.Sogd. ʾ(n)xrwzn, Buddh.Sogd. ʾnγrwzn serve as the names of the zodiac (see Gharib 1995, 40, 47, 82; Henning 1948, 315).↩︎

This mirroring was certainly stimulated by the OAv conception of aṣ̌a as light.↩︎