Turfan

Connecting with Seleucia-Ctesiphon

Despite its linguistic and physical distance from the Mesopotamian heartland, the Church of the East maintained its spiritual and theological heritage amongst its Iranian-speaking communities at Turfan. Psalters written in a wide variety of languages and bilingual lectionaries attest the efforts that were made to ‘reach out’ to the local communities, but it was through the Syriac liturgy that the intrinsic connection with Seleucia-Ctesiphon was maintained. Using MIK III 45, the most complete liturgical text from Turfan, consisting of 61 folios with a C14 dating (771–884 CE), the paper explores the role of liturgy as a tool of community memory. Of prime significance was the commemoration of Mart Shir, the Sassanid queen who eschewed her royal connections to become the evangelist of Marv. Here, the liturgy offers a very different perspective to the ninth-century Arabic Chronicle of Se’ert, in which she was subordinated to Baršabbā, the alleged first bishop of Marv. The prayer of Bar Sauma, bishop of Nisibis, recited plene during the rite for the consecration of a new church (altar), also recalled the close association that had been forged with the Sassanid realms.

Central Asia, Turfan region, Syriac liturgical texts, Church of the East, Seleucia-Ctesiphon

The Church of the East Monastery at Turfan

Between 1904 and 1907, the second and third seasons conducted by the German Turfan Expedition unearthed approximately 1,100 paper fragments, written in Syriac script,1 at the monastery site of Shuïpang near Bulayïq in Turfan2 (figure 1). These covered three major languages: Syriac, Sogdian and Old Uighur; additionally, several fragments in New Persian and a Middle Persian (Pahlavi) Psalter, likewise written in Syriac script, were also found. Theodor Bartus, who was the assistant of Albert von Le Coq, the co-director (with Albert Grünwedel) of the German Turfan Expeditions, excavated the trove in one day from a single spot at the monastery. In his book Auf Hellas Spuren in Ostturken, von Le Coq, who was not present when the fragments were found, wrote that “he excavated […] in the extremely ruined walls an amazing Christian manuscript”3 (1926, 88). Regrettably he supplied no further information about the discovery of the fragments or the monastery, where mud-brick walls still stand to the height of approximately 1.5 metres today. The remarkable discoveries have not shed light on the question of the monastery’s foundation or its lifespan, although the fragments suggest that it may have been operational until the mid-thirteenth or early fourteenth centuries.

The monastic complex possibly provided a stopping point for travelers, since the northern route of the Silk Road, skirting the Tarim basin, passed through Turfan. It undoubtedly also served the needs of the Christian communities distributed throughout the Turfan oasis, as evidenced by smaller quantities of Christian texts in Syriac, Sogdian, Uighur and Persian that were discovered by the German Turfan Expedition at other sites in the Turfan oasis (Astana, Qocho, Qurutqa and Toyoq). A unique fresco depicting a ‘Western’ priest and three female figures that was found at the church in Qocho, and is now housed in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst in Berlin, gives a graphic indication of the diversity of Christian communities at Turfan, who were mainly drawn from the local Sogdian and Uighur populations but may also have included the Chinese (figure 3). The tall, black-haired priest may have come from the ‘West,’ i.e., Mesopotamia, part of the outreach programme implemented by the Church of the East, as described by Thomas bishop of Margâ in his Historia Monastica (Budge 1893). Alternatively his origins may have been in Central Asia, where the metropolitanates of Marv and Samarkand would have had the facilities to train young men. It is also probable that some of the clergy would have been drawn from the local population at Turfan.

Were it not for the discoveries made by the German Turfan Expedition, the monastery would have remained unknown. Synod reports, patriarchal correspondence and other primary sources from Church of the East make no mention of Turfan, possibly because its status was minor; it was not a metropolitanate. Indeed, Turfan possibly fell under the jurisdiction of either Marv or Samarkand, both of which were major centres in their own right. Marv was listed as a bishopric in the 410 CE ‘Synod of Isaac,’ and according to the ‘Synod of Aba’ in 544 CE the city had become a metropolitanate. Samarkand had achieved the status of a metropolitanate by the mid-ninth century (Colless 1986, 52; Hunter 1996, 135–36; Dickens and Zieme 2014, 586). It is also possible that Turfan was under the jurisdiction of Kashgar, a city that was strategically located on the southern rim of the Tarim basin, at the point where the Silk Road to China bifurcated. Two consecutive appointments (John and Sabarisho) made by Patriarch Elias III (1176–1190 CE) confirm that Kashgar still was a metropolitanate in the twelfth century (Gismondi 1896–1899, 64). The medieval listings of ‘Amr ibn Mattai and Selibha ibn Yuhannan cite Kashgar as a joint metropolitanate with Nawakath, the latter being identified as the Sogdian city near lake Issy-Köl in modern Kazakhstan (Hunter 1996, 137 sqq and n.56). 4 This combination suggests that Kashgar’s jurisdiction covered the vast expanse of the Tarim basin and as such might have included Turfan with its considerable Sogdian population.

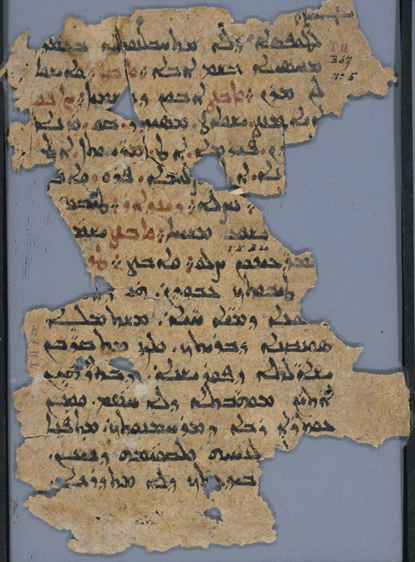

The Syriac fragments found at Turfan encompass liturgical texts, saints’ lives, lectionaries and biblical texts, prayer-amulets and Psalters, imparting multi-faceted insights into both public and private aspects of faith. Redressing the lack of information from official sources of the Church of the East, they form an exceptional collection, not only due to their quantity but also their range of genres. Regrettably, none of the fragments are complete; the colophons that would have imparted valuable information regarding the dating and place of their writing have been lost. The majority of fragments can probably be dated between the ninth and the thirteenth centuries,5 with one manuscript, MIK III 45, C14 dated to 771–884 CE, making it not only the oldest Syriac manuscript written on paper but possibly also the earliest extant Ḥudhrā (Hunter and Coakley 2017, 81–82). Ranging in size from bifolia to scraps the size of postage stamps, each fragment has an individual, intrinsic value; collectively they supply unsurpassed, first-hand insight into how the Church of the East implanted its mission amongst the Sogdian and Uighur communities amongst whom it had proselytized for several centuries.

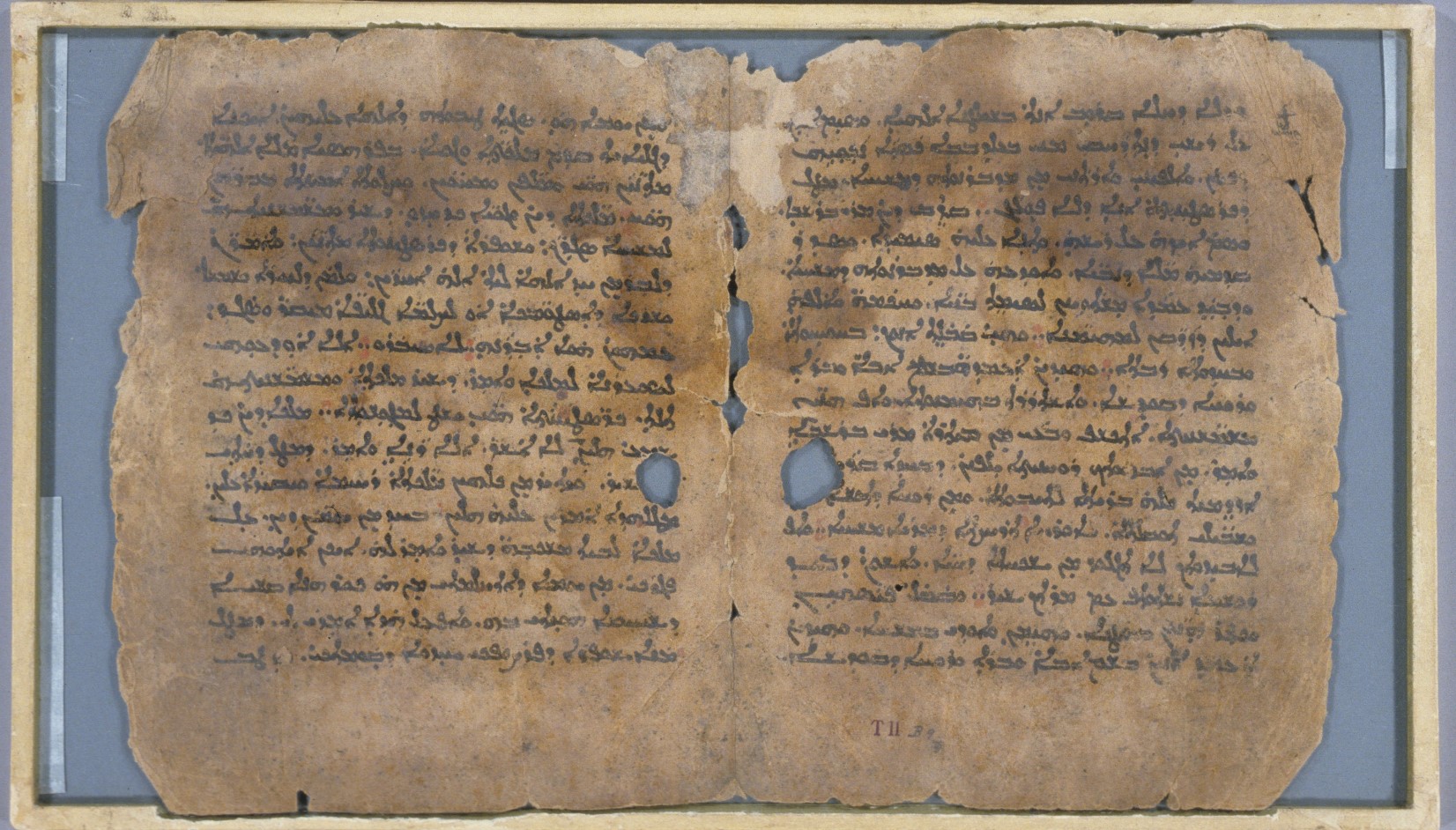

In particular, the significant quantities of liturgical fragments (numbering several hundred) written in Syriac give important insight into how worship was conducted. A small number of fragments include rubric Sogdian instructions to the priest (figure 4). An East Syriac baptismal rite (Syr HT 88), which has been dated “to about the ninth or tenth centuries” (Brock and Sims-Williams 2011, 81), has short instructions in Sogdian. These act as prompts (“the deacon says” and “the priest says”), but some are longer, e.g: “When they finish the priest shall go to the font with the censor and the fans and the [ …] and the cross.” These instructions reveal that some of the clergy were drawn from the local Sogdian-speaking community and were not fluent in Syriac, the language of the liturgy. The liturgical fragments stand in contrast to the Psalter fragments, which are written in a variety of Iranian languages6 to address the needs of the different ethno-linguistic groups amongst which the Church of the East ministered (Dickens 2009, 24). It may be assumed that the local Iranian and Uighur-speaking laity undoubtedly had little command of Syriac, but they participated in the liturgy in the same way that peasants in medieval Europe partook of the Latin mass. Although they may not have ‘understood’ the Syriac liturgy in the literal sense, it performed the vital function of conveying the memory of the ‘mother-church,’ with Seleucia-Ctesiphon being the seat of the Patriarch and the Sassanid monarchy.

Many of the liturgical texts are from the Ḥudhrā, the principal liturgical book of the Church of the East that contained “the variable chants of the choir for the divine office and the Mass for the entire cycle of the liturgical year” (Macomber 1970, 120). These show that the cycle was upheld, in some form, at Turfan.7 At least 21 individual Ḥudhrās (approximately 190 fragments) have been identified on the basis of palæographic and textual criteria, but none is more important than MIK III 45. Consisting of 61 folios, the manuscript lacks both its title page and a colophon;8 it originally was possibly as large as 200 folios.9 In its complete form, MIK III 45 would have offered the full cycle of daily offices and Eucharist for the entire ecclesiastical year of the Church of the East and might be described as some type of ‘liturgical miscellany’ or a ‘Service book.’ The extant contents of MIK III 45 comprise:

Offices for the year (including the saints) [fol. 1?-21a]

-

fols. 1r-7r = Offices for the Rogation, consisting of six Fridays

-

fols. 7r-21r = Offices for saints: week-long observances for

-

Mart Shir and her companions Mar Baršabbā and Zarvandukt (7r-13r)

-

Mar Sargis and Mar Bakos (13r-19r);

-

one-day cycle of offices for ‘all the saints together’ (19r-21r).

-

-

fols. 21a-27b = Rite for the consecration of a new church

-

fols. 27b-33a = Onyata (anthems) for ordinary days

-

fols. 33a-53b = Burial services for all orders (priests & deacons (33a-40b); bnay qeiama (40b-41b)10 and lay people (41b-43b) memre (recited couplets)11 (43v-51v) and prayers (52v).

-

fols. 54b-61b = Onyata (anthems) for various occasions including drought, earthquake, Consecration of the Church, Finding of the Cross, Annunciation, Nativity, Mart Maryam, and Epiphany.

Commissioning the Faith: A Trio of ‘Persian’ Saints

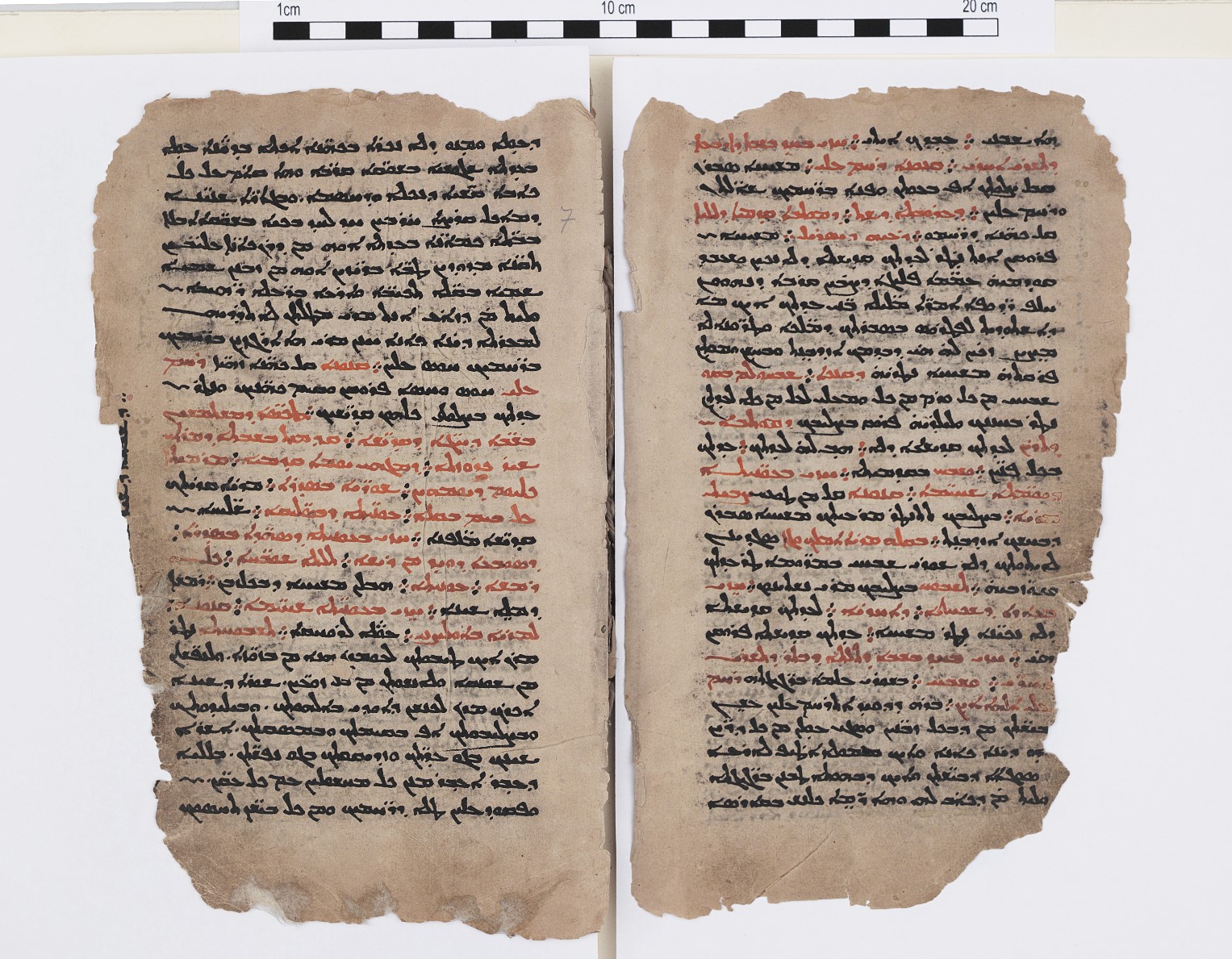

The listing of ‘Offices for saints’ on fol. 7r commences with the rubric heading, “First in the week of Mart Shir, the evangelist” (MIK III 45 fol. 7v l.14 ) (figure 5). In doing so, it places the erstwhile Sassanid queen in the place of prominence. By naming her as “the evangelist,” the lemma of this week-long commemoration explicitly gives her the accolade of bringing Christianity to Marv. Mar Baršabbā, allegedly the first bishop of Marv, 12 and Zarvandokht (daughter of Zarvan), an unknown figure who may have been a lady in waiting to the queen (Hunter and Coakley 2017, 36), are introduced only later in the evening office. The refrain “Two doves and one eagle flew and came <from> Seleucia and Qtesiphon; they made a nest in the branches of the cross. The chicks grew, and flew, sing the praises of the Lord” (MIK III 45 fol. 11v l. 26-fol. 12r l.1) uses ornithological imagery to endorse the integral connection of the three ‘Persian’ saints Baršabbā (the eagle), Mart Shir and Zarvandokht (the doves) with the Sassanid capital. 13 In contrast to the absence of biographical details for Baršabbā and Zarvandokht, Mart Shir’s royal connections are eulogized on several occasions: “Blessed Queen Shir went out from the palace and left her diadem and her honoured state. And she loved the heavenly king” (MIK III 45 fol. 13r ll. 11-13)14 and “How glorious the diadem and beautiful the crown that the Holy Spirit has plaited and puts on the head of Queen Shir. And how much her noble soul rejoices in the band of apostles and priests and martyrs and confessors. In place of the bed of kings that she has forsaken, she sits on a glorious throne in the kingdom at the right hand of the bridegroom of high heaven, at that feast that does not pass away” (MIK III 45 fol. 12r ll. 11-17).15 The emphasis on Mart Shir’s repudiation of her exalted status paradoxically reinforces the connection with the Sassanid monarchy.

MIK III 45 honours Mart Shir as the evangelist, but ornithological imagery is used to show how all three saints were involved in ‘spreading the word’: “In the power of Jesus they went out and came. The three of them, they gave His gospel to Marv. The eagle Baršabbā, and Shir and Zarvandokht the doves. The nest the church in Marv. The chicks, the baptized who sing” (MIK III 45 fol. 12r ll. 3-6).16 The success of their mission is highlighted by the refrain: “who were victorious in the contest […] who laboured in the gospel and turned nations from error to the truth of their faith – let their prayer be a wall to us and guard us from the Evil one and his hosts” (MIK III 45 fol. 12r ll.24-7).17 The premier position of Mart Shir in the “Orders of service observed on weeks of the feasts of the saints” preceding the commemoration of Mar Sergius and Mar Bacchus, the internationally famous Roman military martyrs (Hunter 2016, 97–100; Key-Fowden 1999), created a specific link with Seleucia-Ctesiphon and the Sassanid royal house. It also forged an intrinsic connection with Marv and Central Asia. Such a localized focus may have resonated amongst the Iranian-speaking communities of Turfan.

Discussing Mart Shir, Erica C.D. Hunter and James Coakley have already noted how MIK III 45 presents a “livelier memory of the woman evangelist than the literary tradition in which the glory of the evangelistic work belonged chiefly to the founding bishop of the city” (2017, 32). Here, the liturgy stands in direct contrast to the tenth-century anonymous Arabic historiography, The Chronicle of Se’ert,18 where Mart Shir is subordinated to Baršabbā, the cardinal character in the narrative that details his conversion of the queen, his organization of the church and his miraculous resurrection. A Greek speaker,19 Baršabbā was taken captive during the campaign of Shapur II (309–379 CE) in Syria and was deported to Mesopotamia, where he learnt Syriac and Pahlavi (Scher 1908, 253–54). At the Sassanid capital, he purportedly cured one of the monarch’s concubines, thus gaining royal favour. Baršabbā also healed the king’s sister-wife, Širarân (Mart Shir) (Scher 1908, 254), and, in shades reminiscent of Daniel II, where Daniel was able to interpret Nebuchadnezzar’s dream whereas the magicians, exorcists, astrologers and diviners had failed to do so (Hunter 2013), released her of her demon. When she was baptized, Baršabbā incurred the royal wrath. Outraged by her conversion, Shapur II married his sister-wife to the marzban (governor) of Marv, effectively exiling her to the very extremity of the Sassanid empire. Baršabbā, on the other hand, seems to have remained in the Sassanid capital, for Shapur II, overjoyed at the news of Mart Shir giving birth to a son, later sent him “in grand ceremony” (“en grande pompe”) to Marv (Scher 1908, 256).

The commemoration in MIK III 45 is coloured by its eulogy of Mart Shir, but the Chronicle of Se’ert informs about her activities that laid the foundation for Christianity at Marv. Prior to her exile, Mart Shir ordered the priests to elevate Baršabbā as a bishop, as there had been none in situ since the martyrdom of Barba‘šmin, bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, by Shapur II in 346 C.E.20 Arriving at Marv, she proselytized unceasingly and drew up plans for a church that was constructed and named after the royal palace in Ctesiphon. As a royal woman, Mart Shir would have had the means and presumably the authority to endow the building of a church, but her administrative activities were curtailed by her status and gender. Instead Baršabbā had the task of implementing the mechanics of the faith. The Chronicle of Se’ert informs that he took with him priests and deacons, liturgical books and ornaments, these being the prerequisites to found a new community. At Marv, he consecrated an altar (presumably in the church commissioned by Mart Shir), engaged in baptism (including a large number of Zoroastrians) and cured the ill. His disciples spread the faith, building churches and baptizing (Scher 1908, 256). 21

The legacy of Mart Shir forms the focus of the final part of the Chronicle of Se’ert, recalling how her memory engendered positive relations between the Christians and the Zoroastrians. In what almost reads as a codicil to the story of Baršabbā, the Chronicle of Se’ert relates how, when the Aspahid (army-chief) of Khurasan died, Shapur II22 endowed the position to his nephew, Khošken, and ordered him to marry Zarndoukht, who was the daughter of Širarân (Mart Shir). Khošken and his sister-wife were Zoroastrian but were benevolent to Christians.23 The translation of the Chronicle of Se’ert states:

Khošken was benevolent towards the Christians. His mother, on the point of death, charged him to take care of the churches, protect the Christians and reduce the taxes which had been levied upon them. She recommended these also to the benevolence of her daughter. Both zealously strove to obey and followed their mother’s orders all their life. As to the daughter, Zarndoukht, she confessed the religion of the Magi, which was that of her father […] she had the interest of the churches and the Christians at heart. (Scher 1908, 258) 24

It is noteworthy that, as part of the package of protection, the extra taxes Christians were obliged to pay for the privilege of their faith were reduced. This was a significant move as the poll tax was often a vexation for the Christians under Sassanid rule.25 When Simeon bar Sabbae (Van Rompay 2011, 373–74), the bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon (329–341/4), refused to collect double taxes from his flock, Shapur II imprisoned and executed him.26 The benevolence extended towards Christians by Khošken and Zarndoukht under their jurisdiction was prompted by the memory of their pious mother, conferring real benefits as areas of real friction still existed with Zoroastrianism (Herman 2019, 136–40).

In this context it is tempting to identify Zarndoukht (زرندوخت), who appears in the Chronicle of Se’ert with Zarvandokht, commemorated in MIK III 45. However, such an association would be awkward since as Hunter and Coakley have pointed out: “[i]t is difficult, however, to believe that this notice of Zar(v)andukt, presumably a native of Merv and not even a Christian, could develop into a tradition according to which she was one of the three Christian evangelists who came to Merv from Seleucia-Ktesipon” (2017, 36). 27 Mart Shir, despite her marriage to the Zoroastrian marzban (governor) of Marv, was remembered as an evangelist. It would be extremely unlikely that her daughter, who retained her Zoroastrian faith, would be included in the very public performance of the sung offices of the Evening office, which commemorates Zarvandokht as one of the three saints. Sporting a Middle Persian name, “daughter of Zarvan,” that points to a Zoroastrian background,28 she may instead have been one of the handmaids who converted along with the Queen Shir. A Syriac fragment of Baršabbā’s hagiography (SyrHT 45-46) that was found at Turfan (figure 6) states: “The Queen Shir and three of her handmaids became Christian and repudiated the religion of the Magi” (Polotsky 1934, 562) 29. Regrettably, SyrHT 45-46 gives no further biographical details, but one could suppose that a dutiful handmaid might have stayed with her mistress, in the same way that Theodoret of Cyrrhus noted how, in fourth-century Syria, maidservants accompanied aristocratic Christian women pursuing the ascetic life (Price 1985, § XXIX).

Discussing the hagiography of Baršabbā in the Chronicle of Se’ert, Philip Wood has opined that “if these aristocratic hagiographies celebrate the Christian histories of specific regions, and the connection of aristocratic dynasties to these regions […] then their inclusion in a universal history also subverts this regional emphasis and makes it part of the wider history of the Church of the East” (2013, 171). The linking of the ruling house at Seleucia-Ctesiphon and the Christians at Marv in the Chronicle of Se’ert, prompted by the memory of Mart Shir, had important implications for Christian relations within the dominant Zoroastrian religious landscape of the Sassanid realms, ensuring not the least stability and support for the community. Of course, Turfan never fell under Sassanid dominion, but a Sogdian counterpart (E24/7-11) to Syr HT45-46 that was found amongst the fragments at the monastery attests the narrative’s popularity, as do fragments from a Sogdian lectionary commemorating Baršabbā.30 The Sogdian hagiography, a literal translation of the Syriac original, includes significant information about the localities wherein Baršabbā’s proselytism took root—details that the Chronicle of Se’ert also supplies. The hagiographies had a circulation that was restricted per se, essentially being read by the monks. In contrast, both clergy and laity participated in the veneration of Mart Shir that was sung in the liturgy. Here, MIK III 45 offers a rare insight into the female dynamic of evangelism at Marv; the role and process became subordinated by the male historiographic perspective. By commemorating Mart Shir as “the evangelist”, MIK III 45 recalled the mission of Church of the East, where the connection with the Mesopotamian ‘homeland’ was bolstered through the erstwhile Sassanid queen and her companions.

Maintaining the Mesopotamian Heritage: Remembering Bar Sauma

The Chronicle of Se’ert informs that when Baršabbā arrived in Marv, he consecrated a church. In doing so, he may have followed an order of service similar to that found in MIK III 45: “Next, orders of service and canons for the consecration of a new church” (MIK III fol. 21r ll.16-17) (Hunter and Coakley 2017, 44). 31 The text, that has a series of rubricated instructions revealing the procedure to consecrate the altar, commences:

Let a church be consecrated on Sunday, they having made ready the church beforehand with all its ornaments apart from the veils, which do not hang on the door of the sanctuary. And they wash the altar with aromatic water if it is old, but not if it is a new one. And they make (it) ready with a new <white> cloth; and they set it on the qestroma. And when they have entered for the evening office, if the bnay qyama are many, the bishop enters and the priests and deacons and they stand in the sanctuary, and the rest of the lesser folk in the nave. (MIK III 45 fol. 21r ll.16-16)32

The participation of the entire community, comprising all ranks of clergy and also laity, who stood in different parts (the sanctuary and the nave, respectively), continued throughout the night until:

[…] after two hours of daylight they hang the new veils on the door of the sanctuary and prepare the altar in all its ornament. And all the vessels of the service of the altar they put in a box or in a basket. And a herald summons, and the people gather, and the bishop comes with all the clergy. And a deacon draws aside the veil, and the bishop enters, and the priests and deacons, and they stand in the sanctuary, and the rest of the laity stand in the nave. A series of Psalms are chanted as is the Gloria and then a prayer. (MIK III 45 fol. 22v ll.26-23r l.5)33

Clearly some type of procession took place, for the deacons carried lights and censors, whilst the priests carried in the altar that was to be installed in the church. In so doing, they “lift[ed] it as high as their belts” (MIK III fol. 23r ll.11-12).34

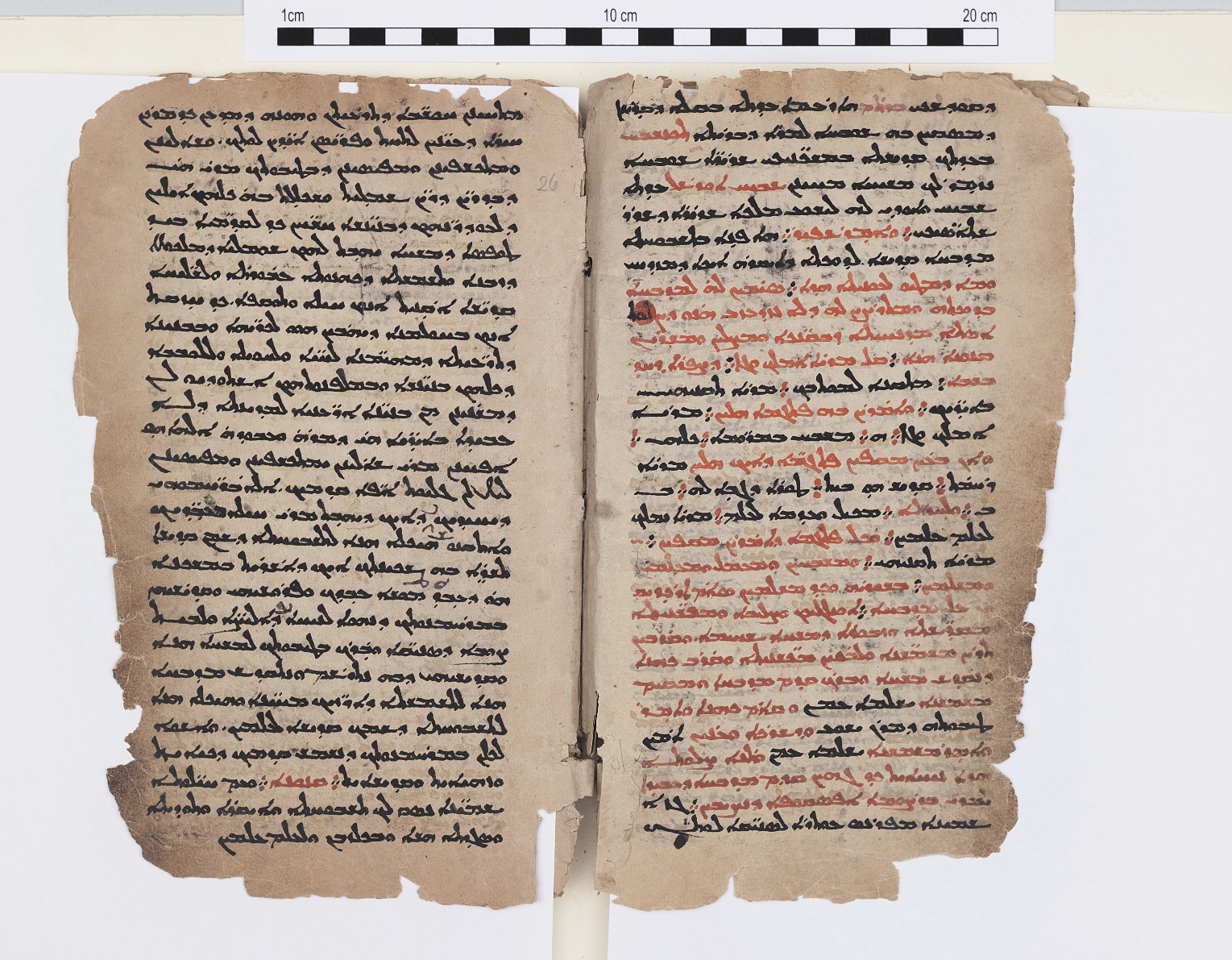

No actual description is given of the altar, but the specific statement that Psalm 89.1-38 should be chanted in a special chant “if however it is an old altar and come[s] from somewhere else” (MIK III fol. 23r ll.15-16)35 indicates that recycling must have been relatively common. Accompanied by a series of onyata (Psalm versicles and responses) (Hunter and Coakley 2017, 19–21) the altar was set in its place, and fixed so that it would not move, with the location being specified as “next to the eastern wall within the sanctuary” (MIK III 45 fol. 25v ll.8-10).36 After the recitation of more prayers, the archdeacon placed the Gospel and the cross as well as consecrated fans and flasks of plain oil on the altar. Two deacons took the fans whilst the bishop approached to sanctify the oil, and knelt before the altar, reciting the prayer of Mar Barsauma, bishop of Nisibis (MIK III 45 fol. 25v l.28-fol. 26r l.26).37 Then various parts of the sanctuary, including the doorposts, were anointed with consecrated oil and finally the top of the altar was anointed with the left-over oil. At the conclusion of the ceremony, various onyata (anthems) were sung, the veils of the sanctuary were tied back and the clergy processed from the sanctuary to the bēma, the platform in the centre of the nave from which scripture lections were read,38 where the Gospel was placed on the altar of the bēma.

The prayer of Bar Sauma of Nisibis occurs at a critical point in the rite for the consecration of the altar in MIK III 45, its recitation being just prior to the anointing of the sanctuary and the altar. With a rubric heading: “And bowing before the altar (the president) repeats quietly this prayer composed by Mar Barsauma, bishop of Nisibis”39 (figure 7), the prayer is reproduced plene:

O heavenly treasure providing riches to the needy, to you | we extend the thoughts (fol. 26r) of our mind and the thinking of our intellect, the gaze of our eyesbeing inclined downward and our hands spread out to you.

And we ask, and supplicate, and beseech that by your grace, Lord, by which from generation to generation you have fulfilled and accomplished all those things useful for the help of humankind –

To those of former times by means of the symbol of oil you gave validity to a temporal kingdom and a transitory service of priesthood.

And you conferred on the holy apostles power and strength, girding them with the healing that they gave to the sick and with the building up of the minds of the faithful to life and to the strengthening and encouragement of all human-kind.

And in their teaching they promised us that we will depart from earthly buildings to the city not made with hands, whose Lord and maker is God.

We too, Lord, ask and supplicate and request, <having> no confidence before you but in the mercies of your Only-begotten, that as you, Lord, gave power to your servants who built this temple to the glory of your holy name, your presence will dwell in it, as you caused (it) to dwell in the tent that Moses your servant made. And set it apart, and sanctify it by your mercy that it may be a refreshment for the distressed and a resort for the needy. And bless with your grace this oil and sanctify it, that by it this altar may be signed and sanctified for the service of your life-giving mysteries, and this temple for the praise of your holy name forever.

And make all of us worthy by your mercy to serve before you purely and virtuously and holily.

The recitation of this prayer was an overt act of remembrance, connecting the newly consecrated altar with the artery of Diophysite theology and, ab extensio, with the Sassanid monarchy.

As metropolitan of Nisibis, Bar Sauma was instrumental in setting up the School of Nisibis, which became the renowned centre of Diophysite learning after the forcible closure of the School of Edessa, following the decree of Emperor Zeno in 489 CE.40 Established initially in a caravanserai, the School of Nisibis imported the legacy of Diophysite theology into the Sassanid realms. Its first director, Narsai (d. 502/3), was one of the great figures of Diophysite learning, piety and asceticism. His reputation, particularly for his poetic works, earned him the sobriquet “Harp of the Holy Spirit” amongst his supporters; by contrast, the Miaphysites despised him, calling him “the Leper” (Gillman and Klimkeit 1999, 117). His Homilies (which still survive), interpreting the great themes of the Bible, championed the theology of Theodore of Mopsuestia (Hainthaler 2019, 383). Known as “the Interpreter,” he was the foremost authority of Diophysite theology; his works became a major part of the curriculum and “the standard for East Syrian orthodoxy” (Baumer 2006, 82; citing Klein 2004, 116, 119). The systematic training of clergy through a fixed program devoted to theological study (Gillman and Klimkeit 1999, 118) 41 meant that the School of Nisibis quickly established itself as the élite institution where “the leadership of the Church of Persia was educated” and from which Diophysite theology was disseminated throughout the vast dominions of the Church of the East by means of a vigorous outreach programme (Jullien 2019, 99).

Much of the success of the School of Nisibis can be ascribed to the efforts of Bar Sauma. Described as “an ecclesiastical politician of the first rank,” the bishop of Nisibis had cultivated good relations with Peroz (459–484) in direct contrast to the stance of his superior, Babowai, Catholicos of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, whom the Sassanid monarch executed in 484 CE for his purported pro-Roman sympathy (Gillman and Klimkeit 1999, 118; citing Vööbus 1965, 109). 42 That Babowai was a Zoroastrianism apostate may also have contributed his fate, as the edict of Yazdegird I prohibited conversion from Zoroastrianism to Christianity, particularly amongst the nobility. Bar Sauma never held the title of Catholicos but, with imperial connections, became the most powerful ecclesiastic in the Sassanid Empire, organising the Synod of Beth Lapat (Jundishapur) in 484 CE.43 It is noteworthy that the synod was identified by its location and not by the name of the Catholicos, as was custom, possibly due to the fact that the position was vacant as a result of Babowai’s execution, although it is unclear whether he had actually died before the synod was convened (Moffet 1998, 196, n.30). At Jundishapur, deep within Persian territory, Bar Sauma had expected to be appointed as Catholicos, but his hopes were dashed when Peroz was killed in battle against the Hephthalite Huns. The incoming Sassanid monarch, Balash (484–488 CE), chose a less controversial man, Acacius (484–496 CE), to whom Bar Sauma pledged his loyalty in 485 CE. He also acknowledged the illegality of the synod that he had organized, even though it was at this synod that “the Church of the East is reputed to have accepted the Nestorian faith” (Baum and Winkler 2000, 28). 44 The support for Theodore of Mesopotamia’s theology culminated in the espousal of the Diophysite stance of the Church of the East at the synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon (Aqaq) that was held in 486 CE. This, coupled with upholding of the Diophysite teaching of the School of Nisibis, had, as Touraj Daryaee notes, “important consequences for Christianity in the Sasanian Empire” (2019, 38).

Concluding Comments

The fragments from the monastery at Bulayïq provide our only knowledge of this distant outpost of the Church of the East that operated for several centuries—possibly as late as the fourteenth century—amongst the largely Sogdian and Uighur inhabitants of Turfan. Otherwise unmentioned both in official sources as well as by East Syrian writers, the monastery must have been representative of many now unknown institutions within the Sassanid Empire and beyond its boundaries. The fragments allow unparalleled first-hand insight into how the Church of the East functioned in its linguistically diverse territories. Sogdian lectionaries and the translation of the Psalter into New Persian and Middle Persian (Pahlavi) as well as Sogdian attest the energetic responses that were made to meet the requirements of the diverse peoples amongst whom missionaries proselytised. This linguistic flexibility ensured the embedding of the faith within the Iranian and Uighur-speaking communities. It was counterpointed by the liturgy that was exclusively in Syriac, functioning to maintain robust connections, both theologically and spiritually, with the Church of the East in the Mesopotamian ‘homeland.’

The recitation of the prayer of Bar Sauma in MIK III 45 during the ceremony for the consecration of the altar graphically upholds this heritage. Written plene, the prayer does not express any overt theological concepts, yet the specific mention of Bar Sauma created a direct link back to the School of Nisibis and Theodore of Mopsuestia, whose theology was espoused by the Church of the East. Bar Sauma’s life was surrounded by many controversies, but his name became traditionally aligned with the triumph of Diophysite theology in the Sassanid dominions. Furthermore, the association that he forged with Peroz cemented the position of the Church of the East with the Sassanid monarchs, who, as Geoffrey Herman points out, “did offer support to the church through donations and the sponsorship of synods” (2019, 139). Connections with the Sassanid monarchy likewise emerge in the public commemoration of Mart Shir in MIK III 45. The eulogistic passages, recalling the origins of three saints with Seleucia-Ctesiphon, eloquently extol the royal status of Mar Shir and her eschewal of the Sassanid court. Her veneration celebrated a saint who founded one of the major metropolitanates of the Church of the East, but also created an aristocratic trajectory with the royal family.

The commemoration of Mart Shir and the recitation of Bar Sauma’s prayer in the liturgy were clearly devotional, serving in the capacity of aide memoire, and in doing so preserved memories of the relationship that had been forged between a distant outpost and the capital, Marv and Seleucia Ctesiphon, perhaps in the same way that the Xian Fu inscription laboured to demonstrate the filial loyalty of the Church of the East to the T’ang imperial court at Xian (Deeg 2018). Of course, Turfan was not part of the Sassanid dominions, unlike Marv, the suggested place of MIK III 45’s writing.45 Questions surrounding the circumstances as to how and when MIK III 45 was brought to Turfan remain to be answered; it may have been for the consecration of a church or another important celebration. The raison d’etre has been obfuscated, but the monks and laity at Turfan who sung the commemoration of Mart Shir in the “Offices for Saints” remembered a great “Iranian royal lady” by whose efforts Christianity had been implanted at Marv, from whence it went further east. The recitation of Bar Sauma’s prayer as part of the rite for the consecration of the altar affirmed the Diophysite legacy of the Church of the East, together with its connections with Seleucia-Ctesiphon and the Sassanid monarchy.

References

Barbati, Chiara. 2015. “La documentation sogdienne chrétienne et la monastère de Bulayïq.” In Le christianisme syriaque en Asie centrale et Chine, edited by Pier Gorgio Borbone and Pierre Marsone, 89–97. Paris: Geuthner.

Baum, Wilhelm, and Dietmar Winkler. 2000. The Church of the East, a Concise History. London: Routledge.

Baumer, Christoph. 2006. The Church of the East. An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London: IB Tauris.

Becker, Adam H. 2008. Sources for the Study of the School of Nisibis. Translated Texts for Historians 50. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Brock, Sebastian. 1995. “Bar Shabba/Mar Shabbay, First Bishop of Merv.” In Syrisches Christentum Weltweit: Studien Zur Syrischen Kirchengeschichte : Festschrift Prof. Hage, edited by Martin Tamcke, Wolfgang Schwaigert, and Egbert Schlarb, 190–201. Münster: LIT.

Brock, Sebastian P. 1982. “Christians in the Sasanian Empire: A Case of Divided Loyalties.” Studies in Church History 18: 1–19.

Brock, Sebastian P., and Nicholas Sims-Williams. 2011. “An Early Fragment from the East Syriac Baptismal Service from Turfan.” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 77 (1): 81–92.

Budge, Ernest Alfred Wallis. 1893. The Book of the Governors: The Historia Monastica of Thomas Bishop of Margâ. 2 vols. London: Kegan Paul.

Burkitt, Francis Crawford. 1904. Early Eastern Christianity. London.

Coakley, James F. 2014. “Manuscript MIK III 45: Introduction and Questions.” In. Berlin.

Colless, Brian. 1986. “The Nestorian Province of Samarqand.” Abr Nahrain xxiv: 51–57.

Dandamayev, Mohammed A., and Rika Gyselen. 1999. “Fiscal System I. Achaemenid, Ii. Sasanian.” In Encyclopaedia Iranica, 639–46. IX/6.

Daryaee, Touraj. 2009. “ŠĀPUR II.” In Encyclopedia Iranica. Online Edition. https://iranicaonline.org/articles/shapur-ii.

———. 2019. “The Sasanian Empire.” In The Syriac World, edited by Daniel King. London: Routledge.

Dauvillier, Jean. 1948. “Les Provinces Chaldéennes ‘de l’Extérieur” au Moyen Age.” In Mélanges offerst au R.P. Ferdinand Cavallera, doyen de la Faculté de Théologie de Toulouse, à l’occasion de la quarantième année de son professorat à l’Institut catholique. Toulouse: Bibliothèques de l’institut catholique.

Deeg, Max. 2018. Die Strahlende Lehre. Die Stele von Xi’an. Vienna: LIT.

Dickens, Mark. 2009. “Multi-Lingual Fragments from Turfan.” Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 9: 22–42.

Dickens, Mark, and Peter Zieme. 2014. “Syro-Uigurica I: A Syriac Psalter in Uyghur Script from Turfan”.” In Scripts Beyond Borders. A Survey of Allographic Traditions in the Euro-Mediterranean World, edited by Johannes den Heijer, Andrea Barbara Schmidt, and Tamara Pataridze, 291–328. Leuven: Peeters.

Garsoïan, Nina. 1989. The Epic Histories Attributed to P‘awstos Buzand (Buzandaran Patmut‘iwnk‘). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gillman, Ian, and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit. 1999. Christians in Asia Before 1500. London: Curzon.

Gismondi, Enrico, ed. 1896–1899. Maris Amri et Slibae. De Patriarchis Nestorianorum. Commentaria, Pars Altera (Amri et Slibae). Rome: Excudebat C. de Luigi.

Hainthaler, Theresia. 2019. “Theological Doctrines and Debates Within Syriac Christianity.” In The Syriac World, edited by Daniel King, 377–90. London: Routledge.

Haiying, Zhao, and Lu Jicai. 2018. “Engineering Properties of Soil of the Xipang Nestorianism Site in Turfan.” 吐鲁番学研究 2018 (1): 111–6.

Herman, Geoffrey. 2019. “The Syriac World in the Persian Empire.” In The Syriac World, edited by Daniel King, 134–45. London: Routledge.

Hunter, Erica C. D. 1996. “The Church of the East in Central Asia”.” Bulletin John Rylands University Library of Manchester 78: 129–42.

———. 2009. “The Persian Contribution to Christianity in China. Reflections in the Xian Fu Syriac Inscriptions.” In Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in Central Asia and China, edited by Dietmar Winkler and Li Tang, 71–86. Orientalia-Patristica-Oecumenica 1. Wien: Lit. Verlag.

———. 2013. “Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream in Daniel 2.” In Leshon Limmudim. Essays on the Language and Literature of the Hebrew Bible in Honour of A.A. Macintosh, edited by David A. Baer and Robert P. Gordon, 227–35. London: Bloomsbury.

———. 2016. “Commemorating the Saints at Turfan.” In Winds of Jingjiao. Studies in Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia, edited by Li Tang and Dietmar Winkler, 89–104. Vienna: Lit. Verlag.

Hunter, Erica C. D., and James F. Coakley. 2017. A Syriac Service-Book from Turfan. Museum Für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, MS MIK III 45. Turnhout: Brepols.

Jullien, Florence. 2019. “Religious Life and Syriac Monasticism.” In The Syriac World, edited by Daniel King, 88–104. London: Routledge.

Justi, Ferdinand. 1895. Iranisches Namenbuch. Marburg: N.G. Elwert.

Key-Fowden, Elizabeth. 1999. The Barbarian Plain: Between Rome and Persia. Berkeley: University of California.

Khoury, Widad. 2019. “Church in Syriac Space. Architectural and Liturgical Context and Development.” In The Syriac World, edited by Daniel King, 476–538. London: Routledge.

Klein, Wassilios. 2004. Syrische Kirchväter. Stuttgart: Kolhammer.

Le Coq, Albert von. 1926. Auf Hellas Spuren in Ostturkistan. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs.

Macomber, William. 1970. “A List of the Known Manuscripts of the Chaldean Ḥudra.” Orientalia Christiana Periodica XXXVI (1): 120–34.

Moffet, Samuel. 1998. “A History of Christianity in Asia. Vol. 1. The Beginnings to 1500.” In, 2nd rev. ed. Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis.

Müller, Friedrich Wilhelm Karl, and Wolfgang Lentz. 1934. Soghdische Texte II. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Payne, Richard A. 2015. A State of Mixture. Christians, Zoroastrians and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. California: University of California.

Pelliot, Paul. 1973. Recherches Sur Les Chrétiens d’Asie Central et d’Extrême-Orient. Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

Polotsky, Hans. 1934. “Barschābba Fragmente.” In “Soghdische Texte II”, Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, by Friedrich Wilhelm Karl Müller and Wolfgang Lentz, 255–8, 559–64.

Price, Richard M. 1985. History of the Monks of Syria by Theodoret of Cyrrhus. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications.

Sachau, Eduard. 1905. “Literatur-Bruchstücke aus Chinesisch-Turkistan.” Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Sitzungder philosophisch-historischen Classe von 23. November) XLVII: 964–73.

Saeki, P. Yoshio. 1937. The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China. Tokyo: Maruzen.

Scher, Addaï. 1908. “Histoire Nestorienne (Chronique de Séert) première partie (II).” In Patrologia Orientalis V. Paris: Firmin-Didot et cie.

Sims-Williams, Nicholas. 1992. “Sogdian and Turkish Christians in the Turfan and Tun-Huang Manuscripts.” In Turfan and Tun-Huang. The Texts. Encounter of Civilizations on the Silk Route, edited by A. Cadonna, 43–61. Venice: Fondazione Giorgio Cini. Instituto Venezua e l’Oriente.

———. 2012. Mitteliranische Handschriften. Iranian Manuscripts in Syriac Script in the Berlin Turfan Collection. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag.

Talbot-Rice, David. 1932. “The Oxford Excavations at Hira”.” Antiquity 6.

———. 1934. “The Oxford Excavations at Hira”.” Ars Islamica 1.

Van Rompay, Lucas. 2011. “Shemʿon Bar Ṣabbaʿe.” In The Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage, edited by Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron Michael Butts, George Anton Kiraz, and Lucas Van Rompay, 373–4. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press.

Vööbus, Arthur. 1961. “The Institution of the Benai Qeiama and Benat Qeiama in the Ancient Syrian Church.” Church History 30: 14–27.

———. 1965. A History of the School of Nisibis. Louvain: Peeters.

Wood, Philip. 2013. Chronicle of Se’ert. Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

-

The author extends her thanks to the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin-Preussicher Kulturbesitz for access to and permission to reproduce images of the relevant fragments. All images are copyright Depositum der Berlin Brandenburgischer Akademie der Wissenschaften in der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Orientabteilung. Low resolution images of the Syr HT signature numbers are available on the International Dunhuang Project website (http:id.bl.uk/; enter the signature number in the search box).↩︎

-

See Barbati (2015, 96) for the geographical co-ordinates of the site. Haiying and Jicai (2018, 111) have published a contour topographical plan of buildings on the site as well as a description, in Chinese, of the buildings. An abstract in English on p. 116 states: “The Xipang Nestorianism site lied (sic) on the hill of the Flaming Mountains in Turfan region is seriously damaged under the action of nature and man. So it’s urgently needed to rescue and protect the Xipang nestorianism site.” David Tam (in personal correspondence) informed me that the Chinese authorities have erected a stone tablet marking the monastery as a provincial heritage protection site. The author thanks David Tam for this information and the publication by Haiying and Jicai.↩︎

-

Translation by the author. The German original reads: “er hat … in dem schauerlich zerstörten Gemäuer eine fabelhafte Ausbeute christlicher Handschriften ausbegraben.”↩︎

-

See also Dauvillier (1948, 287–88) for the listings, with an extended discussion of the identity of Navekath in Dauvillier (1948, 288–90); see Pelliot (1973, 7) for the identification of Navekath.↩︎

-

Dating issues regarding the Turfan fragments are still being determined; however, this period corresponds to the Uighur kingdom of Qocho, where the majority are assumed to have been produced.↩︎

-

See Sims-Williams (1992, 43–61) for a comprehensive survey of materials that included numerous bi-lingual psalters and lectionaries in Sogdian-Syriac, a Sogdian lectionary with Syriac rubrics, a Middle Persian (Pahlavi) Psalter, comprising 12 folios, and a New Persian Psalter consisting of two folios. A unique set of nine folios in Uighur, but written in Syriac script, has been published by Dickens and Zieme (2014, 291–328). ↩︎

-

The fragments from Turfan have the potential to throw much light on question of the transmission history of the Ḥudhrā prior to the fifteenth century, but this area still requires research.↩︎

-

MIK III/45 is complemented by 26 individual fragments, identified as coming from the same manuscript. MIK III/45 folios 20v-21r were edited by Eduard Sachau in 1905 as B26. See Sachau (1905, 970–73). See Saeki (1937, ch. 15) for an English translation.↩︎

-

The bnay qeiama (sons of the covenant) were men and women living in the secular world according to an ascetic rule. See Burkitt (1904, 130) and Vööbus (1961). ↩︎

-

See Hunter and Coakley (2017, 23) for discussion of memre, or ‘metrical homilies,’ in MIK III 45 as isosyllabic lines (i.e. couplets) which were recited or chanted.↩︎

-

See http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/barsabba-legendary-bishop, where Sims-Williams opines that it is doubtful whether there is any historical basis to the legend, it being a pious fiction (last accessed January 4, 2021). See also Brock (1995, 190–201). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 86 (Syriac text), 196 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 89 (Syriac text), 198 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 86 (Syriac text), 196 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 86 (Syriac text), 196 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 86 (Syriac text), 196 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

See Baum and Winkler (2000, 70) for further details. The term ‘Se’ert’ indicates its place of discovery in 1914, not its place of writing. See also Wood (2013). ↩︎

-

Scher (1908, 55) mentions this in connection with the fact that the inhabitants of Marv were descendants of Alexander’s settlement and presumably still spoke Greek.↩︎

-

See Scher (1908, 221–24) for the account of Barba‘šmin’s martyrdom.↩︎

-

The fragments of the Sogdian hagiography give many informative details that are absent in the Syriac counterpart. For the text and translation of the Sogdian hagiography, see Müller and Lentz (Müller and Lentz 1934, 524–25) (fol. 2R ll. 26-36).↩︎

-

Daryaee (2009): see https://iranicaonline.org/articles/shapur-ii (last accessed January 5, 2021).↩︎

-

Translated by the author from original French translation: “Khošken était bienveillant envers les chrétiens. Sa mere, sur le point d’expirer, lui avait recommandé de prendre soin des églises, de protéger les chrétiens et de diminuer les impôts qui pesaient sur eux. Elles les recommenda aussi à la bienveillance de sa fille. Tous deux luttèrent de zèle pour obéir, et cela durant toute leure vie, aux orders de leur mere. Quant à sa fille Zarndoukht, elle confessait la religion des mages, qui était celle de son père […] elle avait à coeur l’intérêt des églises et des chrétiens.”↩︎

-

Dandamayev and Gyselen (1999, 639–46) note that Christians were obliged to pay a double personal tax in certain periods until this was abolished by Shapur II. The collection of personal taxes was traditionally the remit of the heads of the Jewish and Christian communities who were accountable to the king.↩︎

-

Payne (2015, 40–42) discusses the poll-tax that Shapur II levied on Christians, arguing that the execution was not motivated by religious intolerance, but because Simeon bar Sabbae did not uphold his legal obligations. Brock (1982, 8) states that the refusal of the Christians to pay the double tax requested by Shapur II cast aspersions on their loyalty.↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, n. 144) note that another Zarvandukt (in Armenian, Zruanduvt) is known from the Epic histories of P‘awstos Buzand. Here (6.1) she is the sister of Shapur III, given by him to the Arsacid Armenian king Kosrow III for a wife at about the time of the partition of Armenia in 387 (Garsoïan 1989, 265, 434). As the wife of a Christian king she may have become a Christian; but there is nothing to connect her with Merv.↩︎

-

Justi (1895, 383–84) lists names of Zarvan. Although Zarvan was a quintessentially Zoroastrian name, it does seem to have entered the Christian repertoire as Justi’s listing includes Zrovandat, bishop of Gołthn, Geographie von Altarmenien (215, 31). See Justi (1895, 492–93) for listings of Dukht “daughter,” a component commonly found in composite Middle Iranian names. For Christians with Middle Persian/Zoroastrian names, see Hunter (2009, 80–81). ↩︎

-

Translation by the author. German original: “Die Königinnen Schīr und drei von ihnen Dienerinnen sind Christinnen geworden und haben die Magierreligion geschmäht.”↩︎

-

Müller and Lentz (1934, 523) note that the Sogdian text was a literal translation from the Syriac text. See Blatt 1, ll. 1-10. For details of the Sogdian lectionary fragments, see Sims-Williams (2012, 41–42, [E5/127 a-c] and 75-7 for the Baršabbā hagiography [E24/7-11]). ↩︎

-

Despite using “church” in the title, the rite was the consecration of an altar.↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 105 (Syriac text), 209 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 108–9 (Syriac text), 212 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 109 (Syriac text), 212 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 109 (Syriac text), 212 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 112 (Syriac text), 214 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (2017, 113 (Syriac text), 215-216 (English translation)). ↩︎

-

Khoury (2019, Fig. 28.41c) for the Church of El- Ḥira XI where a bema was excavated. For excavation reports, see Talbot-Rice (1932) and Talbot-Rice (1934). ↩︎

-

Hunter and Coakley (Hunter and Coakley 2017, 215) interpolate <the president>. Elsewhere in the consecration of the altar, MIK III 45 uses the Syriac term “the priest,” but as n.3 points out “the bishop must be meant.”↩︎

-

For translation of Syriac texts discussing the “School of Nisibis,” see Becker (2008). ↩︎

-

For the Statutes of the School of Nisibis, see Vööbus (1961). ↩︎

-

Moffet (1998, 196) quotes the letter Babowai purportedly sent to Emperor Zeno that sealed his fate.↩︎

-

Baum and Winkler (2000, 28) point out that this synod was not included in the official records of the Church of the East. They provide a summation of the handful of sources that mention the acts of the Synod of Beth Lapat, in the absence of any records. The fact that the synod was not accepted within the Church of the East points to its schismatic status.↩︎

-

Baum and Winkler (2000) query whether the synod did actually do so. See Brock (Brock 1995, 126) for a discussion of the theological response of the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon to the Synod of Beth Lapat in 486 CE.↩︎

-

For discussion about MIK III 45’s place of writing, see Hunter and Coakley (2017, 14–16). ↩︎