Japanese Concepts of Angels

Analyzing Depictions of Celestial Beings in the shōjo Manga Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne

White wings, long hair, ‘pure’ faces: the appearance of angels frequently follows similar aesthetics connected to Christian imagery. Angels and Christian religion also are popular themes in manga, Japanese comics, often intermingled with Buddhist or Shinto notions. Since imagery in popular culture resonates and shapes vernacular and cultural perspectives, manga like Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne (KKJ) provide an important insight into the conceptualization of angels in Japan. This article therefore analyzes the contrary role of angels in KKJ as the Other, the mysterious, serene one, while simultaneously angels are depicted as part of the circle of life every creature undergoes in Buddhist cosmology. Based on a visual hermeneutic approach, this article demonstrates how the intermix of both visual and religious traditions in Japan shape the depiction of angels in Japanese popcultural media.

Japan, art, manga, Christianity, angels, Buddhism

Angelic Art: Introduction

The angel is a popular motif in artworks, stories, literature, and sacred scriptures. Not all religious traditions have angels, but many speak of celestial beings that accompany gods and goddesses or leaders when wandering through the worlds. Although there are different ideas surrounding the winged creatures hailing from celestial realms, a common angel’s appearance almost always includes white wings.

Angels are also a typical motif in Japanese popular art. In so-called manga, Japanese comics, angels can have very distinct roles, varying from the traditional idea of messengers of the divine to fighters between the worlds, gay lovers, or robots. Even though the usage of angelic creatures and symbolism can be manifold in manga, their appearance is the main nexus: slim, pale-skinned, beautiful, winged, and somehow with the touch of being from another planet.

In the manga Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne, about the reincarnation of Joan of Arc, angels play different roles. For instance, they appear as portraits in picture frames as an atonement for what was stolen by a thief (i.e., the main character erasing demonic powers that reside in possessed art). The images of angels in Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne follow a particular aesthetic and transport a specific idea of what angels look like. By being both an image of something and an image for something, the angels are more than images. Analyzing the depiction alongside the narrative of angels in Japanese manga can instead reveal what kind of concepts of angels are present and thus utilized in Japan.

This article therefore aims at showing how angels are portrayed in the manga Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne and what this depiction may reveal about the conception of angelic beings in Japan. In order to do so, Japanese religious iconography and its roots in Buddhist imagery will be shortly introduced. Buddhist iconography heavily shaped Japanese religious art, and later intermingled with Christian art to form a new artistic tradition after Christian missionaries first entered Japan in the sixteenth century.

Since manga is an important medium of Japanese (popular) culture, it also picks up religious ideologies, traditions, practices, and symbols and builds stories around them. Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne stands as one example of how manga use and work with religion and form new storylines around religious themes. Because comics and manga are influential media of communication, shifting the attention towards this rather new medium in academic discussion will help reveal how art and religion work in witnessing and establishing cultural meaning and conceptions. Traditional media, Buddhist scrolls and imagery as well as statues, laid the foundation for Japanese manga. Therefore, the theoretical concept this article draws from is media, which has been shaping religious contacts and ideas from East to West significantly.

The answer to how angels are depicted and imagined needs to be empirically investigated as a means to understand which function (mass) media have in the creation and portraying of religious imagery in light of transnational religious contacts. This article is a starting point for a necessarily multi-layered and multimodal analysis thereof. In order to investigate manga as an example for mass media, it thus uses sequence analysis established on the basis of theories from the sociology of knowledge, focusing on uncovering underlying structures of meaning found in the visual and, in this case, simultaneously, textual material. The results will be discussed with theoretical approaches by Jolyon B. Thomas, Naoko F. Hioki, Neil Cohn and Koichi Iwabuchi, before a final conclusion shall summarize the overall results of this study.1 My results show a tendency of intermixed visual and religious traditions that are used to portray angels in manga. They are presented to incorporate two contrary aspects: the serene, out of this world, and a part of the circle of life every creature undergoes.

Traditional Religious Imagery in Japan

In her dissertation The Iconography of Kami and Sacred Landscape in Medieval Japan, art historian Meri Arichi explains that there is not much evidence of religious2 imagery before Buddhism was introduced to the southern parts of Japan in the sixth century. Since Buddhist and Hinduist traditions are widely known to be image-heavy, it only makes sense that their rich visuality would leave traces wherever it went. Believers of the various kami3 beliefs defined their gods as creatures that “manifested themselves as invisible natural energy” (Arichi 2002, 114). Displaying them as human-like statues would not be an adequate representation of their imagined nature (Arichi 2002, 114–15).

When Buddhism came from Paekche, Korea, to the Japanese archipelago in the sixth century, it was accompanied by icons, imagery, and a material culture yet foreign to the Japanese conception of religion.4 From the greater icons and the smaller sculptures arose slowly but surely a new artistic tradition of religious craftsmanship and imagery (McCallum 2001, 132–34).

The Buddhist tradition that was (and still is) prevalent in East Asia is called Mahāyāna (‘great vehicle’).5 Compared to the Theravāda tradition (‘the teaching of the elders’), a tradition that is primarily spread across South Asia and Southeast Asia, Mahāyāna Buddhist thought emphasizes personal devotion to the Bodhisattvas and Buddhas as well as universal salvation supported by Bodhisattvas, whose accumulation of special merits shall be shared with the devotees once they die. This is reflected in the Mahāyāna art that arose in East Asia: the first Buddha—often meekly displayed as a working, serving, virtuous being in Theravāda Buddhist pictures—appears in an abstract manner. Supernatural powers belt his presence, which is commonly located somewhere in-between the earthly, heavenly spheres in extravagant palaces. Celestial beings and flying figurines accompany the Buddha, creating a rather heavenly atmospheric splendor (Fisher 1993, 11–14).

The Mahāyāna imagery became pivotal in Japanese religious visuality within a few decades as Buddhism rose to more popularity in the sixth century. It did not take long until kami were included in the Buddhist pantheon, either as Bodhisattvas or deities. As the Japanese religious landscape bears many visible tokens of a complex and persistent religious hybridity,6 there are many cases of kami who were visually portrayed in the Buddhist tradition. By incorporating the indigenous kami into the pre-existing yet foreign cosmovision, Buddhism could easily incorporate some Japanese kami by explaining kami as being the manifested traces of the real/original entity of the world. This process started in the Heian period and shaped Buddho-Shinto relations for centuries.7 This meant that kami were subsequently understood as another manifestation of Buddhist deities, which led to a spatial addition of a Buddhist sanctuary in the early shrines. This whole process was called honji suijaku, ‘original entity and manifested traces.’ According to honji suijaku, kami are only the traces of the original form that the Buddhas left behind when on earth. This combinatory idea integrated Buddhism into the Japanese worldview and created a hierarchical relationship between kami beliefs and Buddhism that hailed from outside (Teeuwen and Rambelli 2002, 2–7). For this very reason, historical findings of kami iconography need to be traced back to the Asian Buddhist iconography. Only after many decades, a unique visual Shinto tradition developed and paved the way for what is now coined kami shinzō, kami imagery (Arichi 2002, 115–18).

The icons appear to bear witness to a very sophisticated and active culture of devotion. Votive objects, relics, and artefacts were placed beside well-carved statues whose eyes were made of glass, and laid into the orbital cavity (e.g., the so-called shaka at Seiryō-ji, Kyoto/Japan). Some icons were believed to sweat, bleed, or shed tears, while others are said to have grown facial hair (Faure 1998, 781). Bernard Faure comments on these ideas of living Buddhas, explaining that “Asian icons, because of their verisimilitude, their mimetic quality, are able to arouse people” (1998, 781), and links this to stories that reveal a close relationship between phenomena around Buddha statues and a person’s life (e.g., sexual arousal and imagined intercourse with a Buddhist deity, whose icon suddenly had a stain of blood on her gown). Other accounts refer to a sculpture’s sweat as bad omen, forewarning of coming disasters or floods. The relationship between religious icon and actor could be interpreted as rather intimate. Faure continues:

The intimate relationship between the icon, the god, and the believer can also be observed in China and Japan in the cases of people who, in times of drought, attempt to coerce the deity by making its icon suffer from exposure to the sun, or by throwing the icon into the water because the god has failed to protect them from a disease. (Faure 1998, 780)

In what image were the icons created? There are many studies devoted to the complex history of Indian, Buddhist, and East Asian art discussing the aesthetics and handicraft of religious imagery with its specifics. Many Buddhist icons and statues were made in the traditional fashion of Indian art with a focus on female representation in the early years. The female portrayal was mostly influenced by early Indian religious goddesses connected to nature, fertility, and creation. In East Asia, especially, female imagery was strongly linked to the idea of good fortune and luck. This is why later female Buddhist art followed the visuality of female kami statues and icons that by then had evolved from their primordial Buddhist roots into kami iconography. Buddhist iconographical features often include Buddha as seated and in a calm position, with eyes closed and a content face (Fisher 1993, 21–26).

Buddhist imagery from Gandhara is particularly interesting when looking for early representations of winged or celestial creatures in Buddhist iconography. Early imagery of small angelic creatures called putte already seems to be out of the norm and must have been influenced by early Roman and Greek art, as Anna Provenzali notes in her work on infantile figurines in art from Gandhara (2005, 155–73). Although the basic attributes of the figurines are similar to Indian Buddhist art (Bodhi tree or gestures), due to the isolation of the Gandhara region its art did not align with the mainstream tradition in India. The region of Gandhara (north of today’s India and Pakistan, west of Afghanistan, and south of Tajikistan) was invaded by different intruders during its long history. Besides the neighbouring empires taking turns in trying to incorporate the region, the Greeks under the rule of Alexander the Great greatly influenced the local culture. Buddhist icons found in Gandhara are an example for this: they resemble early provincial classical art styles from Greece and Rome. The faces of Buddhist icons share semblances with Roman facial features and clothing, like the toga, a garment highly inapt for the meteorologic circumstances in Gandhara (Fisher 1993, 44–47). “The Roman love of portraiture and dramatic realism appeared in form of images of the emaciated Buddha, a favourite subject of the region but one seldom found in Indian Art” (Fisher 1993, 47). In a way, Gandhara became a second holy land, besides India, which Buddhist pilgrims traveled to, a reason why some pieces of art were later brought to further parts of Asia on trade routes.

Many temples in Japan bear paintings and architectural elements displaying celestial beings. These celestial beings in Japanese Buddhism are called either hiten (flying celestials), tennyo (celestial maidens, mainly used for goddesses), or tennin (heavenly being),8 which are theologically differentiated and have distinctive roles within the cosmology of Buddhism. What is important here is the fact that art works depicting these celestials often include flying garments and bodily positions that indicate a flying motion. As servants to higher beings, e.g., to the Buddha, they praise and worship with music and are thus depicted with musical instruments. In many cases, the faces and clothing resemble female characteristics (Fisher 1993, 11–14; Howard 1986; J.A.A.N.U.S. 2001a). They usually have black hair and slim faces with almond-shaped eyes. There also are anthropomorphic celestial beings called karyōbinga. They possess the body of a bird, resembling sparrows, and the head of a Bodhisattva in visual representations (J.A.A.N.U.S. 2001b). Especially regarding both the role and the portrayal of hiten and karyōbinga, similarities between Christian and Buddhist ‘heavenly beings’ are easily detectable.9

Christianity and Japanese Art

Asian Buddhist art and iconography rearranged religious iconography in Japan for centuries with a constant flow of new findings from abroad and the indigenous transformations of new Buddhist traditions. However, Japan was not isolated from the world for most of its history, so sooner or later European explorers, missionaries, and traders would make their way around the globe, trying to spot land they had never stepped on. Japan became one of the favored destinations after China was already being canvassed.

While the first Europeans coming to Japan were from Portugal, and unfortunately shipwrecked on their way home from China, three Spanish Jesuit priests were the first Christian missionaries to step on Japanese soil in the sixteenth century; most prominent of these three men is Francisco Xavier. With time passing and more people converting, a conflict of trust between the authorities and the priests slowly emerged, which subsequently affected the relationship of the two groups. Somehow following the ideal ‘the more the merrier,’ it was quantity that mattered rather than the quality of conversions (Suter 2015, 10–16; Whelan 1996, 4–8).10

Within the next few decades Christianity became a symbol of Western invasion and in consequence was persecuted. The circumstances put the converts under pressure and forced them into the underground, having to get rid of all material evidence possibly linking them to Christianity. Since the Jesuits did not train them to be priests, there were no ordained leaders amongst them. Most of their knowledge was thence made up of memorized scriptures, songs, or sermons (Suter 2015, 17–22; Miyazaki 2003, 13–15).

In this time of dearth, the hidden Christians as well as all other citizens were obliged to register with a Buddhist temple to support the local site financially as an active part of the so-called danka-system, and to uphold this membership during their lifetime.11 If people reacted with reluctance, they could face punishment, including political harassment, loss of civil rights, or death. Whilst some Christians decided to live out their faith and thus became martyrs, others tried to find another way: They registered as Buddhists officially and kept Buddhist statues in their homes. Simultaneously, they would meet up with fellow Christians in secret to encourage one another and jointly practice prayer. In the underground they would craft figurines that resembled both Buddhist and Catholic religious iconography in order to stay incognito, which will be discussed more extensively in the next section (Habito 1994, 145).

Nevertheless, most Christians “virtually disappeared from the surface […] [and since they] made every effort to avoid leaving written traces, there is little information on their numbers, their location, and their activities. They […] gathered to pray collectively in secret” (Suter 2015, 23). It was in this specific time of persecution and anti-Christian propaganda that a kakure kirishitan (hidden Christians) culture developed.

In the following decades, the political emphasis on persecuting Christians slowly decreased, leaving behind only a vague memory of a once Christian Japan. Japan, which was by then a unified country, began to follow the ideal of political isolation to strengthen a Japanese identity. This political decision also led to additional reluctance to the Christian doctrine and culture, which is why there was not much evidence of an active Japanese Christian culture when the country was forced to reopen its gates to the world in the nineteenth century (Suter 2015, 23–26).

Christianity in Contemporary Japan

Keeping these historical circumstances in mind, it may not be surprising that only 2% of contemporary Japanese nationals are affiliated with Christian churches or organizations. The tendency to hybrid religious practice is a continuous element in the religious landscape. Scholar of religion Ian Reader showed in his book on Religion in Contemporary Japan that many Japanese people often do not tend to make a clear distinction when practicing religion. At the grassroots level, it is more about religious practices than doctrines. When looking at various religious rituals, ideas, doctrines, and sacred spaces in a snapshot, a flourishing and religiously interchangeable practice with elements from Buddhist, Shinto, Christian, and folklore traditions can be witnessed within both the busy streets of buzzing cityscapes and the more traditionally rooted countryside (Reader 1991, 1–4).

Although many Japanese would not refer to themselves as religious—a result of the complex history of the concept of religion in Asia and its connection to religious violence—, some polls and surveys mirror an interesting idea of religious life: According to a survey by the Japanese government conducted between 1950 and 2004, Japanese affiliate with Buddhism and Shinto simultaneously and have traditional household shrines (butsudan in Buddhism and kamidana in the Shinto tradition) in their homes, while also going to the temple or shrine for special occasions such as the New Year. Other studies, such as one by the Japanese General Social Survey (JGSS) from 2003, suggest different results concerning the number of Shinto adherents, however still showing that only a small percentage (3,45% of the sample) reported an affiliation with Christianity (Roemer 2009, 300–306).

Despite the low number of Christian adherents in Japan, Christian culture has influenced Japanese culture in some areas. Universities and schools all over the country are associated with Christian founders or missionaries, but a more popular example can be found in (commercial) festive culture: Christmas decorations and illuminations as well as Valentine’s Day decorations are popular commercial strategies for the winter, although not directly linked to Christian connotations. This may be due to the relatively strong impact American tradition had on Japan during the military occupation after World War II (Barkman 2010, 26).

Another very interesting case of Japanese adaption of Christian cultural elements is the idea of getting married in a white dress in a traditional Christian church. Wedding chapels are therefore very widespread, and their architecture is reminiscent of different styles of Western churches. Many Japanese couples decide to tie the knot under the eye of a Western priest12 and opt for ‘typically Western’ wedding traditions such as the white wedding dress, cake-cutting, and exchanging wedding bands. Wedding chapels are often connected to a venue for the reception. Research suggests that this development is related less to religious shifts but rather to sociocultural developments in Japanese society, representing a symbolic abandonment of values once formulated on the basis of Shinto ideals and neo-Confucianism during in the nineteenth century, e.g., a focus on the family (Löffler 2011, 260–65).

Hybrid (Religious) Art

As said before, hybridity of religious practices was one of the defining factors of the ‘Christian’ era of Japan. This is not only apparent in religious practice but also religious art. This section will shortly introduce two areas in which Western and Eastern religion and devotional art became interwoven and consequently present crucial evidence for a longer tradition of Western-inspired art in Japan.

Especially in the eye of persecution and menacing execution, converts in the seventeenth and eighteenth century turned to old ways and incorporated their newly found faith in traditional worship to stay incognito. One striking example is the so-called Maria-Kannon worship—a practice combining Holy Mother Mary and the Buddhist goddess Kannon—, because it not only shows the process of merging different religious ideas but also bears witness to the amalgamation of Buddhist and Catholic devotional art in Japan. Maria-Kannon statues and imagery can hence be considered important sources for both early Buddhist influence on creating Catholic devotional art in Japan and for Western influence on Japanese religious art (Suter 2015, 33–34).

Who is Maria-Kannon? After the opening of Japan in the nineteenth century, the world first learned of Japan’s kakure kirishitan and their lives in oppression. When their houses were discovered and examined in academic research, petite statues that bore both Christian and Buddhist features were found. These statues are the essence of a specific hybrid Christian-Buddhist practice an unknown number of hidden Christians turned to during the time of affliction. At first glance, the statues resemble the Bodhisattva Kannon, who still is an important figure in the Buddhist pantheon.13 A more contemplative look, however, reveals details of Holy Mother Mary (Habito 1994, 145).

Hybridised religious practices started during the time of oppression. On the one hand, the newly converted Christians had to turn their backs on Catholic devotional arts, rosaries, statues, and scriptures to avert any suspicions (Reis-Habito 1996, 51). On the other hand, Buddhist practice was favored by the country’s leaders, and thus a “popular devotion to Kannon had spread in different areas throughout Japan, and so the image of this Bodhisattva of Compassion was a familiar feature in Buddhist temples and homes” (Habito 1994, 146; Wakakuwa 2009).

In Chinese Mahayana Buddhist texts, Kannon’s character and devotion to the people were particularly discussed. Kannon’s portrayal underwent various stages of transformation, from being called a good man and depicted with a moustache to being imagined as a motherly woman holding a child. “The shift towards a female form of Kannon, clad in a white garment, took place in the Tang-China period (618-907)” (Reis-Habito 1996, 53).

In Japan, Kannon and the religious practice around this Bodhisattva were already famous during the time of the arrival and ministry of the Jesuits. Moreover, there are even older reports of people pilgrimaging to Kannon statues in order to strengthen their faith in the Bodhisattva that saves. Likewise, research found accounts of people who would call Kannon statues by the name “Santa Maria,” and others even spoke of Mary as a Buddhist deity (Reis-Habito 1996, 53–55).

Whilst Maria-Kannon statues first showed a woman with a baby boy in her arms, they were later reduced to a female figurine due to heavier persecution. How was it possible that Mary could be visually disguised as Kannon? The iconographic similarities of Kannon and the Virgin Mary are key in this discussion: Although the Jesuits brought Catholic art with them, or rather demanded that Rome send devotional and secular art to Japan (Hioki 2011, 28–31), Japanese converts soon started to craft their own statuettes of Mary and Jesus Christ. The visuality of Mary slowly underwent a process of indigenization insofar as the imagery of Kannon’s female statues were used as a model. The result of this visual convergence between the Japanese crafting of devotional art, Buddhist iconography, and Catholic notions finally culminated in the birth of a specific imagery of Maria-Kannon (Shin 2011, 13).

Visual Bilingualism and Hybrid Art

Maria-Kannon is one concrete example of a conflation of devotional art and religious notions that developed among the circles of kakure kirishitan. Nevertheless, the Jesuit missionaries and other European visitors brought along more than religious ideas and statues that had an impact on Japanese culture, including European art, art pieces, and different styles. After these objects reached Japan, they became sources of European influence on visual art—an encounter that resulted in so-called ‘Early Western-Style Paintings’ from Japan (Hioki 2011).

When the Jesuits started ministering in Japan, they would bring secular and religious art objects to the authorities as presents. Images and visual art were very important tools in their missionary activity, for the language barrier created a gap very difficult to overcome. Visual art, however, enabled another way of introducing ideas and notions due to its specific mode of communication. Additionally, since paintings of war scenes were famous in Japan, the Jesuits tried to bring paintings with analogical subjects to Japan as a tool for ministry. These images used by the Jesuit missionaries and those brought to Japan by Dutch and Spanish traders later became the references for a corpus of Western-style paintings by Japanese artists from the seventeenth century. These paintings show clear resemblances with Western artistry, motives, coloring, and composition, whilst they also portray, e.g., European missionaries, traders, and ships. Little is known about their background, but scholarly work suggests that some of the artists could have been trained by the Jesuit missionaries, especially considering that the paintings seem to highlight Catholic symbolism as if it surpassed ‘pagan’ art, i.e., Japanese symbolism (Hioki 2011, 25–29; McCall 1947).

Naoko Frances Hioki discusses these Western-style paintings by portending a “visual bilingualism” detectable in the paintings and their reception. She underlines her argument by mentioning how differently these paintings were perceived by the Catholic audience in comparison to the Japanese, non-Christian, audience. The motives and scenes of the paintings could convey multiple meanings that co-existed, allowing the paintings to speak in different languages to different audiences. Hioki thus explains that to a Christian audience, the paintings were understood as Christian art displaying Biblical scenes, while Japanese/non-Christian viewers might have focused on the beauty of the landscape or the activities rather than recognizing specific religious symbolism. Moreover, Hioki refers to a religious bilingualism visible in the Japanese Western-style paintings, which is connected to the Japanese tradition of Buddhist iconography. The conglomeration of new religious ideas from Catholic Christianity and traditional notions was then visualized by using elements from two traditions of art, forming an overarching aesthetic bilingualism (Hioki 2011, 41).

Manga

Since this paper is concerned with analyzing representations of angelic creatures in manga, Japanese comics, the genre itself needs to be shortly introduced. Manga form a specific category of literature and art that is distinguishable from Western comics in regard to structure, styles, and stories.

Mange are popular products in and beyond Japan, and their sales are important in the Japanese and global market. The number of publishers and translators is rising, and some fans even go to unofficial translation services on the internet to read the newest chapters of their favorite manga or explore manga that have not yet reached the West (Thomas 2012, 4–8). While manga (and Anime, the animated cartoons in a similar style—a whole culture in itself) were perceived as rather exotic products in the American market, European countries like France and Germany integrated the art forms more creatively into their everyday television program, which later led to a smoother acceptance of Japanese popular art. An example of this is the popularity of series like Alpenmädchen Heidi (Darling-Wolf 2015, 104–9).

Aside from that, manga have a long history with religious traditions in Japan. Therefore, manga and its history and influence will be presented to show its connection to religion(s) and specifically Christianity. Following these general remarks, a description of the object of discussion, Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne, and its storyline shall serve as an important basis for the analysis in a later section.

Manga as Japanese Visual Language

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), the famous Japanese artist who painted “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa” (kanagawa oki nami ura), first used the term in sketches published after his death (Brunner 2009, 26). His paintings alongside a variety of woodblock prints called ukiyo-e reached Europe from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century as traders returned home. Their impact on Western art is most apparent when studying the style of japonisme, e.g., paintings of cherry blossoms by Van Gogh (Johnson 1982, 348). But the imagery imported to Europe during that time is far away from what is considered manga in contemporary Japan. The specific characteristics of manga are what makes the medium stand out amongst other comic traditions. First of all, aside from covers and special illustrations, manga is almost always in black and white. Color contrasts are added by using screen tone, different shades of grey and black, and sometimes black and white photographic elements. For the most part, early manga were hand-drawn using ink and quills, but with the development of technology, manga authors and artists, mangaka, started utilizing software and digital tools. Manga are read from right to left, following the Japanese traditional way of reading books, and they consist of panels and speech bubbles, sometimes featuring columns by the mangaka (Thomas 2012, 3–4).

Manga are primarily related to the category of comics. In short, comics are both visual art and literature. They work with panels and speech bubbles, can be short snapshots like caricatures or long stories such as Marvel’s Spider-Man. However, it is a rather difficult endeavor to define an academic category for comics, or even an adequate term to use, due to different factors:

First, comics have traditionally been mass-market products and continue to be so, mutatis mutandis. Second, they can be as short as a handful of panels, or they can be hundreds of pages long. Third, they are a global genre that draws on distinct traditions as well as on an important cross-cultural dissemination machine that features translations, cooperations between publishers and creators, and movie and web adaptations. Fourth, they are a hybrid genre that is both visual and literary, but that generally does not privilege text over image. (Labio 2011, 124)

The term “graphic novels” is recently becoming more popular within scholarly circles but can be criticized because it lacks the capacity to refer to the vast variety of comics (Labio 2011, 124). Furthermore, some voices in the academic discussion suggest treating comics as the ninth form of art due to their aesthetics and cultural significance.14 Formerly intended solely as mass products for illiterate people, comics were incorporated in magazines and newspapers before they slowly but surely gained a standing on their own. Comics as well as manga were born as media of a sub-genre, often understood as mere phenomena of popular culture. Nowadays, the establishment of comic museums, comic schools, and the development of an academic field—in short, the institutionalization of comics—indicates that they must be taken into consideration more in anthropological, sociological, historical, and finally religious and religious studies discourses (Schmitz-Emans 2011, 243–44). Manga are widely known as cultural products of Japan, but this is only party true: The way manga are produced (and used as reference by people from different places) today is the overall result of intercultural exchanges, interwoven traditions in artistry, and economic and social factors.15

Neil Cohn explores a mode of manga that shows resemblances with what Naoko Frances Hioki meant by the term visual bilingualism: Cohn’s hypothesis is that manga (and comics, too) communicate through a distinct language which operates through visuality. He calls this phenomenon “visual language,” and, in the case of manga, assumes there is a “Japanese visual language” (JVL) one needs to be able to read (and “speak”) in order to understand manga (Cohn 2007, 1–2). Hence, there are different cultural styles of drawing that intermix with written words in manga and comic, forming a visual language that has a particular ‘grammar’ or system of rules. The mangaka/comic artists/authors and their viewers/readers become a visual linguistic community (Cohn 2007, 2–3). JVL is also copied by its speakers (i.e., manga readers). This is apparent not only in studies with Japanese school children drawing in typical patterns of JVL, but also when looking at non-Japanese mangaka from all over the world that make use of JVL to create their own manga.16

The development of the current state of JVL took its time, and early mangaka were inspired by Walt Disney or French comics (bande desinée), just like languages keep on evolving and integrating neologisms and loanwords into their vocabulary. Characters drawn according to current JVL follow a “recognizable pattern — the stereotypical big eyes, big hair, small mouth, and pointed chins of characters in manga” (Cohn 2007, 3–4). Added to this are special facial features or vividly colored hair. The variation of styles within this more general pattern can be perceived as different dialects, influenced by varying factors, i.e., other visual languages. In this regard, manga genres like shōjo (young girls’ manga) or shōnen (boys’ manga) not only use distinct themes in their stories but also apply JVL patterns in a different way (Cohn 2007, 4–8). There are distinct motives linked to specific meanings—a metaphorical way of communication is thus typical in Japanese manga. When looking at visual symbols in JVL used in shōjo manga, examples of this are seen in the background when “pastiches of flowers or sparkling lights [are used] to set a mood or hint at underlying symbolic meaning,” or when sex is “often depicted through metaphoric crashing surf or blossoming flowers” (Cohn 2007, 7). Other particularities of JVL include the so-called super deformed (SD) or chibi (tiny) characters to show spontaneous or humorous situations, and speed lines to show activity and quick movements in scenes (Cohn 2007, 8–9).

Universality of Manga

Although manga employs, from a comic and literature studies perspective, a specific kind of visual language that Cohn describes as distinct from other comic traditions, Iwabuchi Koichi attests manga and Japanese pop-cultural exports like Anime and games with the peculiar quality of being mukokuseki:

The cultural odor of a product is also closely associated with racial and bodily images of a country of origin. The three C’s I mentioned earlier are cultural artifacts in which a country’s bodily, racial, and ethnic characteristics are erased or softened. The characters of Japanese animation and computer games for the most part do not look ‘Japanese.’ Such non-Japaneseness is called mukokuseki, literally meaning ‘something or someone lacking any nationality,’ but also implying the erasure of racial or ethnic characteristics or a context which does not imprint a particular culture or country with these features. (Iwabuchi 2002, 28)

Understanding manga in this sense of universal applicability, Iwabuchi highlights that the new aesthetic approach to design points toward a Japanese inventiveness. This, however, must be critically reviewed, as voices have increasingly suggested a unique Japaneseness which Iwabuchi sees as problematic.17 Yet, although the Japanese products that are very successful in the Western world are aesthetically designed without a cultural or ethnic flavor of Japan, they have prompted a kind of Japanization in some parts of the world. The euphoria over manga, Anime, and video games from Japan hence resulted in a euphoria about Japan. Iwabuchi poses the question that if people yearn for the Japan presented in pop-cultural exports, then isn’t it a culture-less and race-less Japan they wish for? He sees similar developments with regard to American popular icons, too (2002, 28–35, 152). This culturally odorless quality of manga significantly explains the applicability of manga to diverse places transnationally in Asia and, ultimately, the Western world.

Religious Manga

Manga and religion have historically been closely intertwined for many centuries. This is to say that the term manga was not used prior to the twentieth century, but the possible origins of contemporary manga are rooted in Buddhist visual-narrative picture scrolls called emakimono. The emakimono were initially created in China, but later reproduced in Japan. Usually created by literate monks, the scrolls told Buddhist stories and tales by combining imagery and scripture. They would also depict the lives of famous or influential monks or Buddhist icons. Even in the early days of Buddhist arrival in Japan, they already portrayed sequences of images to show movement or time leaps—a method still in use in manga. Japanese scrolls were also unfurled in steps, hence creating a narrative for the viewer. This was different in China, where scrolls were normally completely unfolded before reading. Since illiteracy had yet to be overcome in Japan, the profession of etoki-hōshi—one who explains the scroll—thrived and would long impact the Japanese culture of telling stories. Etoki-hōshi would unfold the scrolls in front of an audience and, by fusing explanation and role-play, would narrate and perform the contents of the scrolls. Therefore, rather than scriptural pieces, a tendency to dialogic texts can be seen in later scrolls. However, with economic changes and social and technological advancement in regard to prints and duplication, pictures with dialogues gradually became mass products circulating in Japanese society (Brunner 2009, 22–24).18

In spite of the manifold ways manga has taken since its formation as a medium, religion is still a very important topic in many stories. Jolyon Baraka Thomas delivers a thorough analysis of the interrelation of manga and religion in his monograph Drawing on Tradition: Manga, Anime and Religion in Contemporary Japan (2012). Religion and manga accordingly interact on different levels, involving the display of religious practice, religious people, sacred sights, religious history, and religious devotion. There is a variety of manga explicitly dealing with religious contents, for they function as material for missionary activity or for information (e.g., Kumai’s (2006) Manga Messiah). More prevalent, however, are stories about either religious characters or religious sites (e.g., Hikaru Nakamura’s (2006) Saint Young Men about Buddha and Jesus living as roommates in a modern world, Chrono Crusade (Moriyama 1998) about a nun and a demon hunting satanic creatures, Osamu Tezuka’s (1997) Buddha about the Buddha’s life, Vatican Miracle Examiner (Kaneda 2012) about investigators looking at miracles in the Vatican).

Aside from these explicit representations of religion, where religion(s) and their ideas are very important to the storyline, there are manga that implicitly depict religion by using symbols, names, and terms, or by showing religious activity in everyday life without putting emphasis on the religious part but rather displaying ‘Japanese everyday life/culture.’ Examples with implicit representations of religion include Naoko Takeuchi’s (1992) Sailor Moon (one character lives and works at a Shinto shrine, hence she wears traditional clothing and uses religious talismans) or Hyōka by Honobu Yonezawa and Task Ōhna (2012), in which the characters occasionally go to different shrines and temples during typical festival seasons in Japan, such as the hatsu-mōde, visiting the shrine on New Year’s day).

In a way, manga therefore impact religion in many ways, one of them being the recreation of religion(s). By depicting either religious contents or religious traditional practice, a version of religious notions is (re-)introduced to the readers. This is sometimes perceived as negative because some manga allegedly misinform readers about certain religious ideas when elements of a religious worldview are altered. Although the assumption of modifying, and thus corrupting, authentic religion still lingers on in the conservative discussion, manga also preserve (with different degrees of fidelity) some religious traditions by bringing them to the readers (Thomas 2012, 2–5).

A particularly important account is famous producer Hideaki Anno’s (1995) Neon Genesis Evangelion (NGE). In this science fiction series about an apocalyptic version of Tokyo, people in giant mecha-robot suits called Evangelion have to fight so-called Angels. The Angels are almost unfathomable creatures, powerful and abstract in form, enigmatic, yet genetically almost human. They may be interpreted as resembling the Other but cannot be easily thrust aside due to their relatedness to humans (Napier 2002, 425–30). According to Anno, the creator of the series, the many different ways of how NGE can be interpreted are intentional. Christian religious symbolism, Judaism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Shinto are referenced alongside philosophical and psychoanalytical elements. As a story situated in between the beginning of life and an apocalyptic end of the world, Anno’s anime and the subsequently published manga series (almost a canon to some extent) tie together different views and modes of the world with techno-animistic conceptions that could be read as a criticism of Japanese society (Rayhert 2018, 163–67).

NGE is therefore a prime example of ‘playful religion,’ shūkyō asobi, a term employed by Thomas (2012) to describe different modes of the interplay between religion and entertainment, since Anno and his team modify existing religious motifs and intermix different traditions.19 Thomas explains that to understand why and how religion is displayed in manga, it is necessary to comprehend the Japanese concept of religion. Scholars who investigate Japanese behavior that could be categorized as religious come to the conclusion that it is an active part of Japanese cultural life. Japanese people do not necessarily call what they do religious, yet their behavior illustrates the importance of applying a culturally appropriate concept of religion rather than a Western one (Thomas 2012, 5–9). Thomas gives examples of behavior he classified as religious:

For example, trips to historic temples and shrines […] form a large part of domestic tourism, and people make seemingly casual trips to local and regional shrines and temples to petition the deities for worldly benefits (genze riyaku) such as academic success, luck in marriage, help in securing divorces, healing, and so forth. (Thomas 2012, 10)

Taking this rather behavior-oriented conception of religion into consideration and juxtaposing it with the tendency mentioned earlier to integrate and hybridize religious traditions in Japan, it becomes clear that religion(s) in Japanese manga do exactly the same: They show religious behavior, deal with different religious traditions, add and take ideas to/from specific traditions, and generally depict religion in a more fluid and open way than most Western media would (Barkman 2010, 27). Since Japanese people engage with media that deals with religion more as audience and consumers, adherence to religion or personal spirituality is often less important than the aspect of being entertained (Thomas 2007, 76).

Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne (KKJ)

One religion that frequently appears both explicitly and implicitly in manga is Christianity, although Christianity is not a widely practiced religion. The degree of alteration of Christian doctrines, history, powers, ideals, and beings varies, and oftentimes Christian imagery and topics appear on the scene with other religious themes, which is when new formations of religious interplay emerge. For this reason, female Cardinals or gay angels exist in manga and Anime—a strange sight to the Western eye (Thomas 2007, 26–29).

Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne (hereafter: KKJ) is one very intriguing example of explicit depictions of Christianity in Japanese manga and Anime. KKJ’s narrative refers to Christian history and doctrine as much as it probably astonishes and confuses some readers brought up in an environment outside of Japanese culture. From 1998 until 2000, KKJ was created by Arina Tanemura and published in the publishing company Shueisha’s manga magazine ribon in Japan (a revised version was published in 2013). Shortly after that, French, English, and German translations and publications followed (2001–2003). Due to its quickly growing popularity, Toei Animation Studies created an animated version and broadcasted it on Asahi TV in 1999. The Anime was broadcasted in Germany roughly two years later, too (“Jeanne, Die Kamikaze Diebin” n.d.).

The manga KKJ belongs to the supracategory shōjo manga (manga for girls). Since the main character is located in a fictional world fighting demons with supernatural powers, KKJ can also be categorized as fantasy and magic, and more specifically, within the genre magical girl (Shueisha).20 16-year old Maron Kusakabe, the protagonist, leads a double life: During the day she studies at a Japanese high school with her friends and by night she lives out her calling as the reincarnation of Joan of Arc and turns into Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne to slay demons with the help of God’s power. Demons subverting the world are sent by the King of Evil with the task to possess humans. They enter visual objects such as portraits and paintings, and from there charm the people engaging with the objects. In order to save the people possessed by the demonic powers, Maron activates a divine artefact in the shape of a cross (called rosary) with the support of the apprentice angel Fin Fish. She then transforms into Jeanne and renders the demons harmless by calling upon God’s help. As a result of God’s intermission through her she receives a small chess piece, and the images disappear. Instead of the former motif, a substitute image of an angel magically takes its place. The angels are called tenshi in the Japanese original, written with characters referring to heavenly messengers or messengers from heaven (Tanemura 1998).

Angels as Characters in KKJ

The mangaka Arina Tanemura frequently uses Christian symbols, angels, or names in her works (e.g., the symbolism of the cross in Shinji Dōmei Cross). In KKJ, however, the whole story revolves around the idea of the incarnation of French Christian martyr Joan of Arc. Archangels, the King of Evil, God, paradise, Eve, and Adam appear alongside linguistic references to the power of God, love, evil, good, truth, and spiritual needs. There are different angels portrayed throughout the manga. The appearances of each angel—its clothing, celestial features (wings, halo, powers), makeup, facial expressions and gestures—vary according to roles they play in the story. There is a hierarchy of angels that distinguishes advanced, full angels from angels in training or semi-angels. A short explanation of the different types of angels will serve as the basis upon which the analysis will be presented.

As explained in the latter part of the story, angels are the reincarnation of ‘pure’ human souls. The purer they are, i.e., the less evil they have inside themselves, the stronger their spiritual powers and energy are. They enter heaven, a fleeting place in the sky, to join the ranks of kuro-tenshi, black angels.21 Black angels, i.e., angelic being with black or greyish wings, strive to become sei-tenshi, pure angels with white wings. Once they reach the rank of pure angels of a high standard,22 some are granted the chance to visit earth to bathe in the sunlight, which will give strength and spiritual renewal to them. The primary goal is that they would receive a spirit or soul of their own which may be able to reincarnate. The angels Jeanne leaves behind as portraits in the frames after expulsing the demons, as well as the angels Maron later meets in heaven, can be considered full-fledged angels or dai-tenshi, great angels. They ‘work’ at the heavenly palace and take care of the angels of lower rank. As such, they appear as gatekeepers, mentors, and powerful creatures. In a dialogue, one of the great angels explains to the reader and to some pure angels that as angelic beings, they possess a part of God’s power and are thus mysterious spiritual beings. For the angels in KKJ, hair plays a decisive role. Not only does their hair contain their spiritual power (and the longer the more powerful the angel is), but its color also shows the angel’s rank. Great angels have golden hair, pure angels possess white hair, and Fin Fish, Maron’s angelic friend, has special green hair. She is also enormously strong. When angels give part of their hair to another angel or being, they also transmit their power. In the case of Fin Fish, the removal of a part of her hair resulted in a big de-charging of power which killed a human being (Tanemura 2000a).

There also are the semi-angels, jun-tenshi. Fin Fish and her male counterpart, the angelic friend of Maron’s love interest and rival Nagoya Chiaki/ Kaitō Sindbad, Access Time, function as messengers between the human world and the heaven. They enable humans to transform by transmitting spiritual power to them. Both characters undergo the several stages of angelhood and finally also receive a soul, as both are reborn as children of the two main couples of the series. Fallen angels make up the last category. Fin Fish is a fallen angel for a time. Her fall is connected to her allegiance with the formless evil that evolved from God’s abandoned sorrow. As fallen angel, she could still work as semi-angel and utilize God’s power, who did not recognize or care for her fall. Fallen angels can turn back into pure angels once supported by other angels or by God (Tanemura 2000a).

Methodological Considerations

Analyzing the combination of text and image in manga is not an easy task, because comics are not easily categorized due to their dual nature. Text and image are different media operating as two distinct modes of communication. Therefore, KKJ must be analyzed on both levels of communication simultaneously. American comic artist and scholar Scott McCloud established a groundbreaking first methodology of how comics could be analyzed in regard to panels, narrative, and design. His works lay the groundwork for comic analysis (McCloud 1993). There are two methods for comic analysis that develop McCloud’s ideas further (Dittmar 2008; Eckstein 2013). Both methodological takes on tackling the complexity of the twofold medium allow an understanding of how panels, structure, styles, and graphic elements are used by the authors and what they are supposed to represent, although they cannot illustrate underlying motifs and meanings by solely reviewing the way a manga is constructed. Nevertheless, there remains the problem of how to examine the way manga themselves speak of underlying conceptions through the displayed material.

A helpful tool to get to the bottom of what the material tells a researcher can be found in German sociologist Ulrich Oevermann’s methodological works. Oevermann and his students established objective hermeneutics, a methodology embedded in theories from the sociology of knowledge which has since been widely discussed, especially in German methodological and sociological debates. In short, the primary goal of objective hermeneutics is to deduce underlying structures of meaning as transmitted in linguistic or text-based material. Stemming from this methodological notion, Oevermann promotes a similar strategy to be used toward visual material. His primary idea in both textual and visual analysis was that at first only the material matters; researchers using his methods are required to erase their memory of any knowledge that refers to the material. Concerning images, he argues that visual material converts only a small portion of knowledge—once already existent knowledge is assigned to what is represented in an image, it evolves into a vessel of knowledge. Contextual knowledge has to be temporarily unlearnt in order to look at what is immanent in the image (Oevermann 2014, 36; Wernet 2014).

Taking this into consideration, Gregor Betz and Babette Kirchner entrenched the Sequenzanalytische Bildhermeneutik (“sequence analytical image hermeneutics,” see Betz and Kirchner 2016), offering a refined technique of analyzing images based on what Oevermann and fellow sociologists (of knowledge) argued for. The Sequenzanalytische Bildhermeneutik (hereafter: sequence analysis) takes advantage of the necessary sequential nature of sociological understanding by operationalizing it systematically. It is divided into three analytical steps: (1) the division of the visual material in segments (sequences) as reasoned according to the data, (2) the sequential hermeneutic reconstruction of the image (other methods to be incorporated in this step), (3) the interpretation of the context of formation and function within the respective area (Betz and Kirchner 2016, 263).

The fundamental goal is the exposure of underlying structures of meaning, referring to what and why humans act the way they do and how that can be recognized in visuality. Since this method is specifically designed for the analysis of visual data (pictures, photos, or other graphic material), it tries to investigate them in their entirety present to the viewer right away. Betz and Kirchner add the interpreting human being into the equation, thereby trying to reconcile the difficulty of the simultaneous and likewise sequential nature inherent in visual material: sequence analysis is a tool that allows identifying the construction of meaning in a methodologically controlled manner step by step (Betz and Kirchner 2016, 264–65).

Sequence analysis is designed to be conducted with a group of researchers to provide a wide range of interpretative knowledge and a variety of approaches to the visual material. During the whole analysis, the researchers try to channel emotions, associations, and ideas evoked by the material. It operates on three crucial premises connected to the notion that formal structures must be defined from within the visual material, which justifies a processual interpretative procedure. Accordingly, the chronological dimension or linearizing of comprehending the visual data shall be included in the analytical process. Betz and Kirchner admit that linearizing the material can pose difficulties due to its (oftentimes unreflected) nature; nevertheless, they postulate this as the starting point of the methodological process. When conducting this method, the researcher divides the visual data in different sequences. The authors suggest looking for areas with symbolic agglomeration and working one’s way from the seemingly most important to the most trivial parts, which later will be looked at first.

Thematizing peripheral sequences at first gives way to the development of distinctive Seharten (modes of viewing). These modes evolve in the analytical process and facilitate interpretative suggestions, which can be discarded or affirmed with further advancement of the analysis. Secondly, the common way of looking at the data must be irritated systematically. This serves the aim of focusing on one segment/sequence without distraction when following the chronological order established in the first step. When looking at images and visual material in a common manner, highly charged symbols, and orchestrated elements appeal to the viewer immediately, leaving an imprint on the first impression and the general perception of the material. By irritation of the gaze, all elements of the imagery may be looked at on an almost equal level, a means of trying to avoid a biased analysis. Lastly, the visual material needs to be reconstructed as a whole. Betz and Kirchner’s method also enables the researcher to use any other method and modification of the methodological conduction in order to fit the visual data (Betz and Kirchner 2016, 266–69).

Since sequence analysis advances best with as many modes of viewing as possible, two further researchers were asked to participate. Among the three German participant scholars, all had a background in religious studies, two additionally came from the field of Japanese studies, and the third also studied art history. All three researchers were familiar with European comics and animation studios like Disney, while only two had formerly engaged with manga as a medium. The third scholar did not know JVL or the hybrid nature of religious manga. This is particularly important regarding Hioki’s theory of visual bilingualism and Coen’s JVL, an aspect that will later be important in the analysis.

On the basis of this mixture of scholarly disciplines, the researchers analyzed the material in only one session to stay within the scope of this paper. The analysis was done in the participants’ mother tongue German and was recorded. The recorded material was then transcribed and smoothed, and thus turned into a so-called case structure generalization including all important and relevant findings.23 The visual material selected for this research consists of four angelic images from the manga KKJ that will be described and then discussed in the next section. The chosen images all appear within the story line and not as cover images, for the cover images were not considered similarly representative of the story as the images used within the story, telling the story to the reader.

Description of the Visual Material

The analyzed visual data primarily consisted of exemplary images of angels from KKJ. For a better understanding, the four analyzed angel images are presented alongside the complete page within which they appear in the manga. A short description of what is pictured is provided before the results of the analysis.

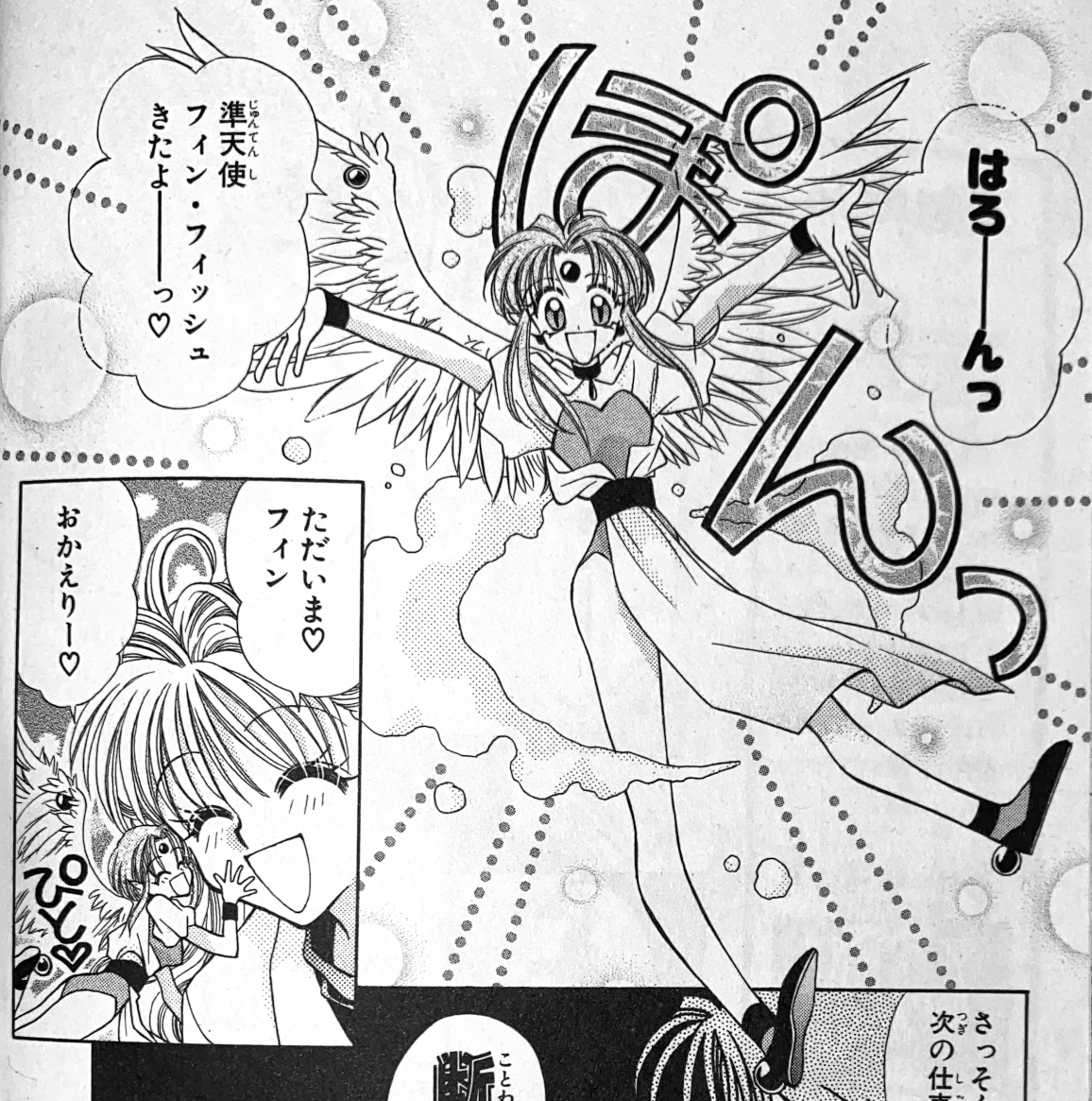

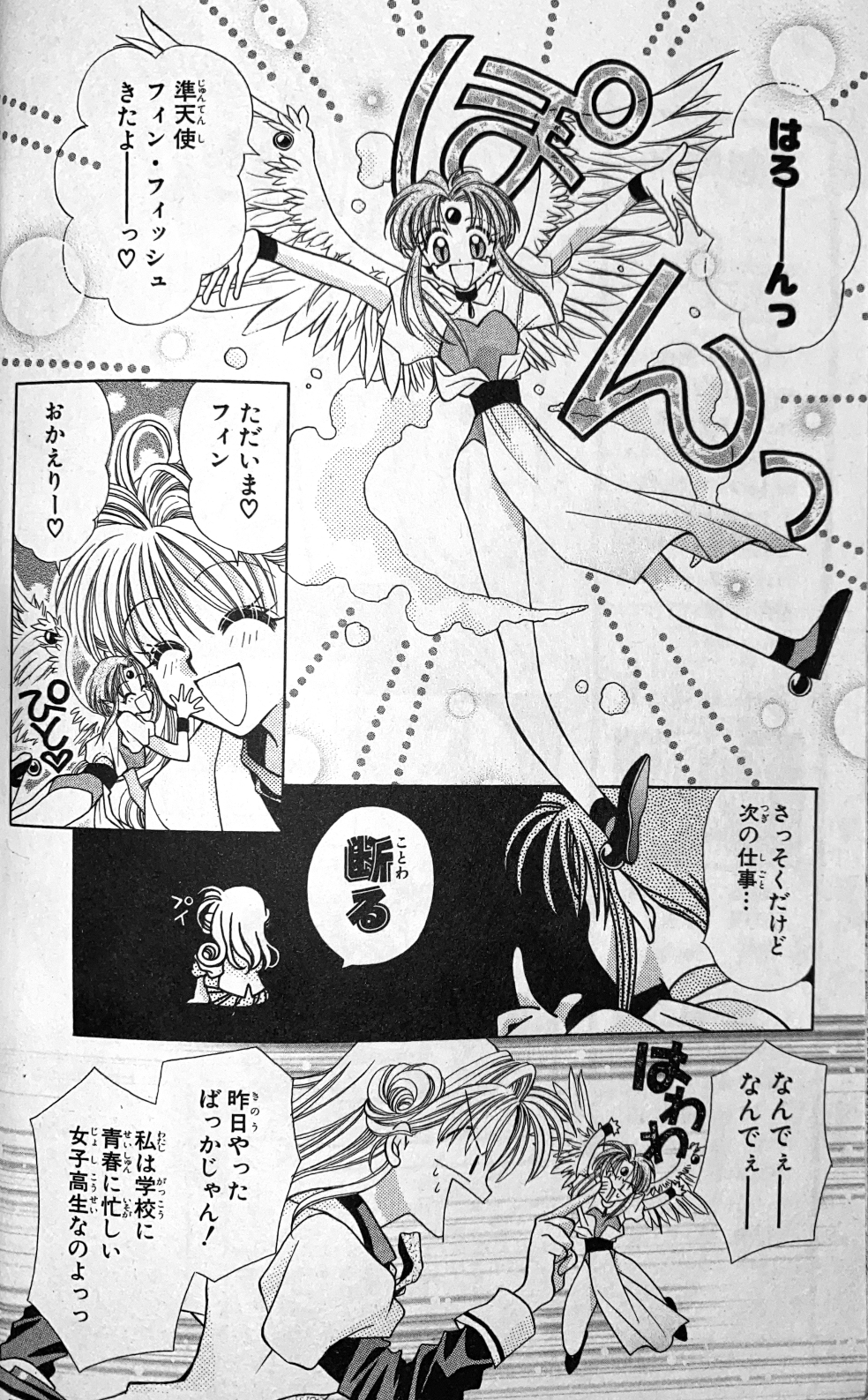

The flying tiny angel Fin Fish is drawn with a joyous look on her face. Her limbs are pointed away from her body, and while her hands seem to be open as if welcoming someone, her legs and feet are merely stretched. She has pointy ears and two wings that are spread open and suggest she is floating. Her hair is short in the back and long in the front. On her forehead and on the edges of her wings there is a circular object that looks like a jewel and resembles two circular decorative elements that seem to be part of her shoes. Her clothing is an interesting mixture of short puffy sleeves, a tight and showing top that is edged by fabric that is held together on her stomach by a dark band. The remaining long end of the fabric hangs from her belly toward her feet and reminds one of a belly dancer or fighting costume used for characters in video games, e.g., Blizzard Entertainment’s character Symmetra from the game Overwatch (“Symmetra” n.d.). She wears earrings and wrist and ankle bands. According to the positive look on her face, recognizable through eyes wide open and an open mouth, she seems to be excited. The background is not depicted with an actual scene but kept mostly white, with small circles and lines that point toward the angel. Around the angel’s hip there is some sort of cloud of dust that indicates movement or sudden appearance. On the right side of the picture a big “pon” is written in Japanese, i.e., a “puff”-sound. The speech bubbles in reference to the angel say “Haroooon!” (speech bubble in the upper right corner) and “Semi-angel Fin Fish is here!” (speech bubble in the upper left center).

Description of figures 5 and 6: This character is depicted with a female-looking face bearing a gentle smile, pointed ears and a delicate facial structure. The woman has her eyes closed. Especially in comparison to the two men in the panel on the left side (see figure 6), the woman is drawn in a detailed manner. Furthermore, the woman’s hair is depicted in great detail, almost floating around her. Over her head levitates a ring, probably a halo. Next to the halo, there are visible wings. There are two men on the left side of the panel and one lying on the street. The men on the left of the picture who supposedly watch the angel’s image create a stark contrast due to their facial expression. The speech bubbles explain the imagery as well as the situation to the readers by verbalizing what the picture is supposed to show. The speech bubbles in reference to the angel say: “Oh, it’s like always. A picture appeared” (speech bubble in the upper left center above the policemen) and “An image of a very beautiful angel” (speech bubbles in right part the center).

Description of figures 7 and 8: A female angel is depicted with eyes closed. She seems to be either flying or bowing. Her hands are softly held together, and she blows petals from her hands. Her wings are spread, and she is seen from a half-profile. She wears a gown or dress, and one part of the fabric covers her left shoulder loosely. Her clothing is heavily draped and suggests that a lot of fabric is centered on specific parts of the gown (shoulder, waist). Her long and darker hair falls down her back. The picture is framed, but the reader can only see a part of it. The background of the framed image is dark, and some flowers can be seen, while petals float around her. This suggests wind or supernatural motions. A speech bubble covers part of her shoulder and wings and again explains the situation. All in all, she looks like a mature, serene woman. The speech bubbles say, “What Jeanne left behind, it’s a picture of an angel” (speech bubble in the upper right corner); “Resembles your mother, doesn’t it?” (speech bubble in the upper left); and “Yeah, that’s true” (speech bubble in the upper left center).

Description of figure 9: The angel has long, dark hair. Since the angel’s eyes do not have long lashes, the angel is identified as male or non-binary (in comparison to all other female characters). He wears a long gown that resembles traditions Japanese or East Asian devotional clothing. The strips, bands, and the complete outfit are reminiscent of the typical kimono and hakama style worn by priests in Buddhist and Shinto groups of Japan. He has a discontented facial expression, and his arms are crossed. His forehead is decorated with a jewel. He also has pointy years and wings that are hidden behind his body. On the far right of the image, there are ornamental leaves in the background that might resemble a wooden or golden architectural element. On the left of the image, the face of the angel is shown again as a close-up. Here, he has a stern look on his face but does not face the reader. On the bottom left, another face (Fin Fish as fallen angel) is pictured with opened eyes, her mouth opened only a little bit. She also has a jewel on her forehead and wears similar earrings. Her face is flushed, as the stripes on her face suggest. On her neck, she wears a band that reminds one of modern chokers or leather bands wrapped around the neck.

Results of the Analysis

The images described above are the basis of this analysis. In the process of the analysis, which proceeded by uncovering parts of the images in a specific order and then the complete pages, the group of scholars developed different modes of viewing that over time were singled out and finalized by the author of this article in accordance with further research, while also taking into consideration the whole story of KKJ, which is a crucial part in this methodological approach.

The imagery used by Tanemura gives hints as to how angels are conceptualized in Japan and what role they may play in the religious worldview. As the storyline of KKJ makes clear, angels in KKJ undergo a personal character development. They start as the spirits of pure humans when their wings are still black. They can become semi-angels under the specific condition of helping a human being as God’s messenger. Their body is then tiny. Magical jewels transmit God’s power to the human being. Artefacts like a rosary are necessary for this process. When they grow as angels, which means increasing their spiritual power through absorbing sunlight, they can become pure angels with white wings (see figure 8).24 The next rank would be that of great angels, who dwell in heaven and educate and organize the black angels. The images Jeanne leaves behind after stealing art (figures 5 and 7) very possibly portray great angels, since they have white wings and a similar look on their face as the great angel character taking care of the black angels in heaven (see figure 2). If they engage with evil of any sort, they fall from grace and become fallen angels that still possess some of their powers.

In KKJ, angels are presented as long-haired human-like beings that differ from humanity not by nature but by status. Aside from their ability to communicate with human beings, each other, and God alike, they can also live both in heaven and on earth, supposedly in need of sunlight to gain spiritual power, which makes them, to some extent, dependent on the earth. The analyzed images all led to the assumption that even when angels live on earth, they are endowed with a specific kind of aura of otherworldliness, as can be seen in figure 3: The angel is pictured with a halo, a motif typically used in Western imagery to demarcate celestial and sacred beings, specifically when appearing alongside profane, mundane people, i.e., the policemen. Similarly, the angel in figure 7 is pictured alongside flowers on a dark and light background, very distinctive from a usual background in everyday life. This transcendent quality is not only represented by the angelic features of their character design (wings, jewels, pointed ears—figures 3 and 4), but also by the indicated effects of wind as if caused by a magnificent power. The angels’ hair seems to move as does their clothing, analyzed as a dominant motif in figures 3 and 5.25

Although the angelic outfits (especially when juxtaposed with that of the human characters) vary in style and according to the angel’s status, the plain gowns with many drapes, the priest-like kimono-hakama combination of Access Time, and the showing outfit worn by Fin Fish all appear somewhat unusual and rather unfitting. While particularly the pure and great angels’ gowns were analyzed as simultaneously meek and magnificent due to the reduced usage of patterns and many layers (see figures 5 and 6), Fin Fish’s outfit strikes one as daring and showing due to the fact that it is really short (see figure 3). In the course of the analysis, it became a mode of viewing that Fin Fish herself occupies a double role as fallen angel in disguise with a complex history. Her appearance as semi-angel (figure 3) analyzed in this sequence analysis was categorized as more on the human side: she fights, falls, transforms. Her facial expression and character traits further emphasize her playful nature, as seen in her conversation with Maron (see figures 3 and 4). She is a strong contrast to the pure or great angels whose faces with closed eyes and calm and mature features were analyzed as representing holiness and a sense of the sacred (see figures 5 and 7, as well as 2). As beings on the brink between heaven and earth, spiritual beings and humans, they are the bridge, the messengers, between God and the human race (see also figure 2 for an example). This resembles the (Catholic) Christian notion that places a third individual in between God and the people, namely a saint, an angel, or even a priest. Their names, like Fin Fish or Access Time, come across as rather special and somehow endowed with meaning, but are vastly different from the other character’s names (such as Kusakabe Maron, the main character).

Additionally, when in the focus of the image, the angels are backed by ornaments (see figure 9), flowers or style patterns that do not resemble the actual background the story is situated in at that moment (see figures 3 and 4). Backgrounds with an abstract or arbitrary imagery are a typical feature in comics and manga for reasons of simplicity or highlighting, and in this case of angelic beings the usage of this layout further underlines the argument that angels are constantly endowed with a suprahuman aura, as the effects of wind used in figures 3, 5 and 7 strongly suggest.

Since sequence analysis was developed to detect immanent social meaning from within the material, the aspects of character design in general and the contrast between the displayed characters and the Asian (stereotypical) phenotype in particular became significant aspects that communicate the idea of angels to be found in Japanese manga. As it is the case for many characters in Japanese popular culture, the angels in KKJ all are light-skinned, and many possess light hair (see figures 5 and 7)—with the exception of Fin Fish’s green hair (portrayed in a light grey in figure 3), Access Time’s purple hair (portrayed as black in figure 9),26 and one pure angel’s dark hair (figure 7). Even though a Euro-Christian theme is central (Jeanne D’Arc), most of the story and almost all characters are based in Japan. With the exception of the angels, the characters thus have Japanese names. Although this must be considered within the wider context of characters in manga, the sequence analysis led to the conclusion that angels in Japan are considered as standing in juxtaposition to the usually dark-haired and sometimes darker-skinned Japanese people, since in figures 5 and 6 the angels were analyzed as an obvious contrast to the other characters due to their hair. At first, this seemed to be farfetched due to the nature of JVL and the way manga (and comics oftentimes too) are drawn. But when this mode of viewing was brought together with the overall artwork of angels in KKJ by the author of this article, it showed that almost all other angels are depicted with light skin and hair (see, e.g., Tanemura 2000a, 2000b, 2000c) (see also figure 2). Because manga are usually painted in black and white, the textual elements are used to explain such aspects connected to color. In the fifth volume (Tanemura 2000a), the meaning of the angels’ hair and colors are mentioned in an attempt to explain where their spiritual powers lie (and why Fin Fish’s hair is different). White and gold are consequently described as representing higher spiritual advancement.

This portrayal of light-haired and light-skinned characters in manga may echo the socio-cultural trends of “whitening cosmetics” in Asia. Since the 1980s, the Japanese beauty market has offered a range of products that bears witness to the preference of a lighter skin complexion (Ashikari 2005, 74). In an article on the influence of whitening cosmetics, anthropologist Mikiko Ashikari further found out that instead of submissively adapting to a foreign beauty ideal, Japanese women use whitening cosmetics to return to what they think is the original complexion of Japanese people. This is mixed with a specific understanding of the Japanese as a race and by that, Ashikari states, “Japanese women are cultivating a Japanese form of whiteness [that is] very different from – and even ‘superior’ to – western whiteness” (Ashikari 2005, 89).

It is important to note that although manga characters, and specifically magical girl characters, are often pictured with light hair colors and fair skin, and thus partly represent a fantasy world, this article tries to discover what kind of concept of angels is conveyed through KKJ. In a way, the angels—and likewise characters like Maron, with their fair skin and thin body (see figure 1)—play into this quest for ‘ideal Japanese beauty’ by transporting the idea that holiness and spiritual advancement are somewhat linked to a specific and exclusive appearance non-representative of most people, whether Japanese or not. On the one hand, this underlines the otherness angels embody as wanderers between heaven and earth. On the other, it also reproduces the idea, with somewhat racist implications, that fair skin is the beauty standard in Japan.

Taking this into consideration, we may detect the whiteness of angels articulated in KKJ as a conglomerate of ideals from both Japan and the West. This reflects what Iwabuchi says about manga being culturally odorless. In reference to Iwabuchi, David Oh explains:

Japan engages with the West in its local space, produces hybrid representations that are an articulation between cultures that is thought to retain a distinctive Japanese essence, and distributes that hybridized text globally back to the West for those in the West to engage in hybridity with an already hybrid text—a deepening circular movement of hybridity that is shaped by global asymmetries that favor Western meanings. (Oh 2017, 373)

This article cannot discuss the problematic issue of whiteness as a beauty standard, for this is not the focal point.27 Nevertheless, it is important to once again emphasize the otherness of angels in terms of appearance as a crucial element that distinguishes them from the other characters. They are representative of the beauty ideal that has long been formulated in both West and East. As they represent beauty and spiritual advancement, Japanese angel conceptions refer to inner-worldly ideals of beauty despite the otherworldliness of angelic beings.

Another aspect which should be taken into consideration is the aspect of angels as representative of maturity, for it became apparent that the pure and great angels are displayed as significantly more mature, calm, and seemingly wise than the lower-ranked angels as well as the other characters (see, e.g., figures 5, 7 and 9). In the course of the sequence analysis, the facial features, gestures, and clothing of the pure and great angels were categorized as qualities of maturity (see the hand placement in figure 5). Rather than having emotional outbursts or striking fighting poses (as Fin Fish in figure 3), the higher the ranks of the angels, the more the artwork suggested tranquility (no harsh movements) and serenity (calm, gentle facial features); this is also visible in figure 2 of the great angel.

Lastly, the sequence analysis revealed that angel conceptions in Japan stem from Western and Asian devotional art of supranatural beings and religious worldviews, as the clothing of the angels suggest (see figures 3, 5, 7 and 9). In the process of the analysis, the religious hybridity that has long shaped the Japanese religious landscape also deeply influenced the portrayal of angels in KKJ. While typical angelic features like wings and halos are obvious reproductions of Christian angelic art (see figure 5), the clothing worn by pure angel Access Time clearly references Japanese religious and traditional clothing (see figure 9). The bold bands and the braided wrap alongside the kimono-like attire are reminiscent of not only miko, shrine maidens, but also of some Buddhist and Shinto priests’ clothing as well as what mountain ascetics yamabushi wear. The robe is not a copy of one type but rather made up of different elements (long sleeves, bands, and layering) that resemble a stereotypical, and somewhat pop-cultural, interpretation of traditional East Asian clothing.28 Additionally, the flying garments and the positioning of angels (see figures 5 and 7) are reminiscent of Buddhist hiten and karyōbinga, celestial beings that serve as messengers or worshippers of higher beings.

As a result of this hybrid portrayal, the mixture of robes and gowns is therefore another example of Iwabuchi’s theory of mukokuseki, since the mixing of clothing allows for different cultural associations and recognizability. KKJ is drawn in a way that it is applicable to different cultural contexts. However, what became apparent during the analysis is the distinct way in which JVL works. Since one scholar was not at all familiar with Japanese manga, the way facial expressions and emotions as well as usage of specific symbolism were difficult to catch for that scholar (e.g., when analyzing the panel showing two policemen in figure 6). The other two scholars (familiar with comics and manga) had learned to read JVL and were easily able to recognize subtle meanings and intended emotional expressions, such as anger (see the character’s face on the lower left in figure 4 and Maron’s face in figure 6). The joint analysis led to a slower and more detailed analysis of each element in the image. As Cohn states, users of JVL can comprehend the stylistic features used to express specific emotions, ideas, or characters. In a way, this challenges Iwabuchi’s thesis of culturally odorless manga. Although the characters in their general appearance can be recognized mostly according to specific material markers (e.g., winged person = angel), the distinct features of JVL made it difficult to read expressions, gazes, and specific motions as well as the way some verbal expressions are presented in some panels. Instead, the analysis showed that despite the overall understanding of the displayed situation or character, the ability of visual bilingualism proved to be extremely important to analyze the imagery. Since Western, Christian features and Japanese cultural elements intermix in the story and art of KKJ, the imagery used by Tanemura resembles this and is thus a conglomerate of both. Hioki’s approach is consequently an important aspect to consider when analyzing modern art.