Red Sea Entanglement

Initial Latin European Intellectual Development Regarding Nubia and Ethiopia during the Twelfth Century

What happens to the ability to retrace networks when individual agents cannot be named and current archaeology is limited? In these circumstances, such networks cannot be traced, but, as this case study will show, they can be reconstructed and their effects can still be witnessed. This article will highlight how Latin European intellectual development regarding the Christian African kingdoms of Nubia and Ethiopia is due to multiple and far-reaching networks between Latin Europeans, Africans, and other Eastern groups, especially in the wider Red Sea region, despite scant direct evidence for the existence of such extensive intellectual networks. Instead, the absence of direct evidence for Latin European engagement with the Red Sea needs to be situated within the wider development of Latin European understandings of Nubia and Ethiopia throughout the twelfth century as a result of interaction with varied peoples, not least with Africans themselves. The developing Latin European understanding of Nubia was a result of multiple and varied exchanges.

Crusades, Nubia, Ethiopia, Red Sea, twelfth century, intellectual history

Introduction

The establishment of the Crusader States at the turn of the twelfth century acted as a catalyst for the development of Latin European knowledge of the wider Levant (e.g., Hamilton 2004). This knowledge was principally gained through direct and indirect interactions with various religious and ethnic groups, each of which acted as individual catalysts for a greater shared development of knowledge. Whilst this continual development of Latin European understandings of broad religious groups, such as Muslims, Eastern Christians, or Jews, has been widely discussed in the Crusades historiography of the recent decades, it has largely ignored the circulation of knowledge regarding the geographies and cultures of some specific ethnic groups within these broader collective groups. Nubian and Ethiopian Christians, for example, are often not included amongst discussions of Latin European entanglements with other Eastern Christian groups, which overwhelmingly centre on Syrians, Greeks, or Armenians as the ‘local’ Christian populations. This article will argue not only that Latin European knowledge—the knowledge transmitted by Christians in Western Europe and in the Crusader States, which were under the jurisdiction of the papacy in Rome—developed regarding these two African groups during the first century of the Crusades, but also that its development was due to multifaceted webs of interaction with both Africans and other knowledge mediaries from various religious and ethnic groups, whilst specifically highlighting twelfth-century interactions within the Red Sea and the wider region.

The Red Sea rarely registers in the discussion of the twelfth-century Kingdom of Jerusalem’s presence in regional affairs beyond detailing a few specific events. Most commonly, discussion of the Red Sea appears primarily in relation to Renaud of Châtillon’s 1182–1183 Red Sea expedition, with some occasional further, often brief, discussion of King Baldwin I’s march to the Red Sea in 1116 (e.g., Böhme 2019; Morton 2020; Tibble 2020). With the exception of the debate surrounding Renaud of Châtillon’s Red Sea expedition, the primary work on the kingdom and its interaction with the Red Sea remains Joshua Prawer’s chapter entitled “Crusader Security and the Red Sea” in his Crusader Institutions (1980, 471–83); yet, despite its name, the chapter focuses largely on Syria rather than on the Red Sea itself. Why, then, has the Red Sea largely evaded discussion in wider Crusades scholarship beyond the two main aforementioned events? It is true that very few Latin European documents survive which attest to any engagement with the Red Sea, either for security or trade. Indeed, the small amount of documentation has led to claims that Latin Europeans were completely absent in the Red Sea prior to Renaud’s 1182–1183 expedition (e.g., Holt 2004, 74). Moreover, according to David Jacoby, only one naval campaign was ever launched throughout the history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem: that of Renaud (Jacoby 2017, 353–54). Does a lack of direct sources, however, necessarily reflect the historical reality once a much larger picture is taken into account?

The Crusader States and the Red Sea

The scholarly discussion on the political presence of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the Red Sea region has been hindered by the debate regarding its occupation of the island fortress at Ile de Graye (modern Jazīrat Firʿawn). The fortress was situated roughly 15 km southwest of the main port of Aqaba at the northern terminus of the Gulf of Aqaba, the eastern arm of the northern tip of the Red Sea, which surrounds the Sinai peninsula. The date of the establishment of the fortress is contested, with only its capture date in 1170/1171 by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn known for certain. The fortress cannot date to earlier than 1116, when King Baldwin I led an expedition to Aqaba, though contemporary descriptions of this event appear to suggest that the Latin Europeans did not cement a permanent presence and swiftly returned to Jerusalem after reaching the Red Sea (Fulcheri Cartonensis 1913, 594–96; Albert of Aachen 2007, 856–59; William of Tyre and Huygens 1986, I:541–542). On account of an apparent reference to a Fāṭimid governor at Aqaba in a firmān from the Fāṭimid caliph al-Ḥāfiẓ to the monks at Sinai in 1134, Hans Eberhard Mayer dated the establishment of the fortress of Ile de Graye to sometime during the reign of King Fulk (reigned 1131–1143) (1990, 54.90). However, Denys Pringle has since urged further caution owing to al-ʾIdrīsī’s reference to the island being populated and controlled by Arabs in 1154 (2005, 334–37), suggesting that the Frankish fortress may only have been in use for a very short time indeed. Whilst Pringle’s caution is warranted, it poses the additional problem that no reference to the fortress is made during any of King Amalric’s five expeditions to Egypt throughout the 1160s (1163, 1164, 1167, 1168, 1169) that would suggest such a late date of construction in connection with any of these movements. Regrettably, due to the fortress’s brief occupation, current archaeology has offered little further light.

This absence in the sources is indicative of Latin European activity in the Red Sea region more broadly and cannot alone reveal the scale and scope of the activity of the Kingdom of Jerusalem along its southern borders. Discussion of Latin European activity in the Red Sea does not require a set date for the construction of Ile de Graye. Throughout the twelfth century, Latin Europeans had some form of presence reaching up to the Red Sea. Specifically, if the Red Sea is viewed more as a permeable frontier than a firm boundary, did any policy of the Kingdom of Jerusalem towards the Red Sea have to centre on an established presence at Ile de Graye? The mightier fortress at Montréal served as the primary insurance policy of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the wider Transjordan, further emphasized by the small-scale nature of the outpost of Ile de Graye. Furthermore, the Latin European presence around Petra should not be considered in isolation either, with the Kingdom of Jerusalem keenly aware of the overland trade routes that their presence in Transjordan could control (e.g., Al-Nasarat and Al-Maani 2014; Sinibaldi 2016). Instead, what remains is the question of how engaged the Crusader States were in Red Sea commerce and political affairs in light of trade being an important concern only slightly north of the Sea?

Whilst the current, limited Latin Christian evidence does not reveal too much on the matter, it is possible to garner a greater picture of the interaction of the Kingdom of Jerusalem with the Red Sea through Latin Christian knowledge development about both the Sea and its surrounding kingdoms, notably Nubia and Ethiopia. The Latin Europeans entered a highly integrated world of trade following the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099. Moreover, it was a trade that was not tightly controlled by Fāṭimid Egypt, which was primarily concerned with taxation rather than asserting direct control over trade (Udovitch 1988). This is further highlighted by the lack of an early Fāṭimid Red Sea policy—the first active intervention in Red Sea affairs was only in 1118—emphasising the Fāṭimid’s initial disregard for an active policy in the region, which was in stark contrast to Fāṭimid naval involvement in the Mediterranean during the twelfth century (Lev 1991, 105–14). What is more, this change in policy has been largely situated amidst Egypt’s relationship with Yemen and has not necessarily taken into account the presence of Latin Europeans (e.g., Bramoullé 2012). Given the precarious position of the early Crusader States, abstaining from engaging with these prosperous sources of wealth would have been detrimental to the Latin European effort; logic alone would have dictated that the Crusader States involved themselves in Red Sea commerce in some way.

How, then, can logic be supported by both direct and indirect evidence? Material and immaterial knowledge is often forgotten as having an active role in trade. It is precisely the notion of knowledge as a commodity—tracing the sources, materials, and products of the continual Latin European development of intellectual understandings of the Red Sea throughout the twelfth century—that can help to shed light on such questions.

The Red Sea Avenues of Knowledge Exchange Prior to the Twelfth Century

The Red Sea had long been an arena of exchange for neighbouring powers, which, importantly for the current study, underwent a clear political transformation during the eleventh century following prosperous centuries since the rise of Islam. Furthermore, this change culminated in a clear twelfth-century decline in neighbouring caliphal oversight in both Egypt and Arabia (e.g., Power 2018) just as the Latin Europeans arrived. Prior to their arrival, the Red Sea had been the venue for interregional trade between the Sahara, northern Mediterranean, East Africa, and Asia for millennia. Significantly for the circulation of regional knowledge, settlement patterns are indicative of the independent political nature of the Red Sea trade during the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, which emphasise that Red Sea communities were first and foremost preoccupied with access to trade rather than with any other ties, thus being potential sources of independent information to tap into (Power 2012; also Margariti 2008). It would be wrong to view the Red Sea as being surrounded by mono-cultural or political blocks which inhibited interaction. Before continuing, a discussion of the local regional interactions around the Red Sea before the First Crusade is necessary to understand the multifaceted dimensions that Latin Europeans were entering and their primary localities of exchange: the African Red Sea ports, the Arabian Red Sea ports, and Aqaba.

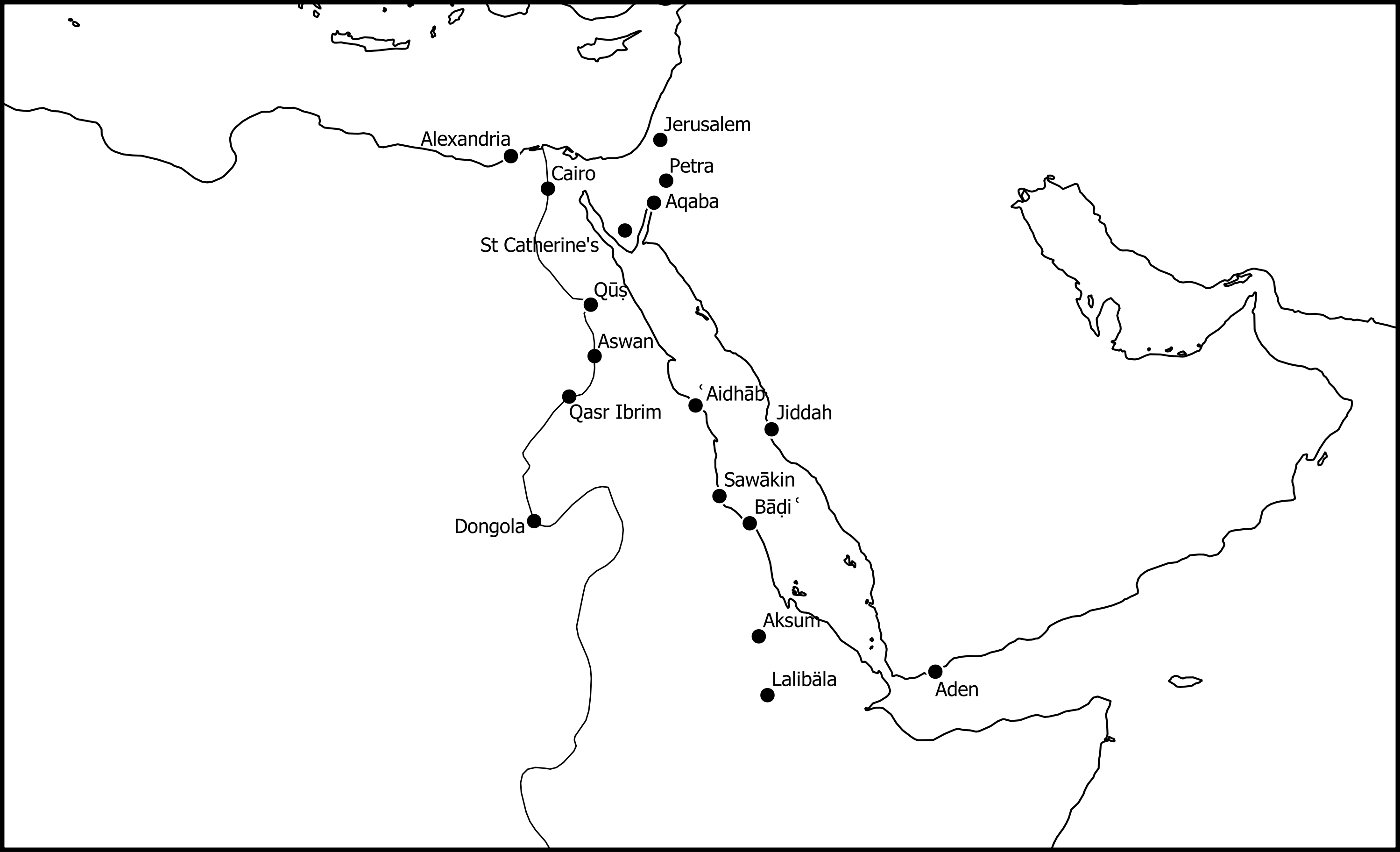

Prior to the Crusades, the Red Sea had undergone a monumental shift in its trade and politics since the ninth century. No longer was the Islamicate world a unified political force controlled by the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate centred in Baghdad, with independent politics becoming established in Egypt (the Ṭūlūnids: 868–905) and Yemen (the Ziyādids: 818–1018). Increasing competition within the Red Sea region had an immediate effect on trade, which had stagnated during the early centuries of Islam (e.g., Shatzmiller 2009). Previously, trade had been prosperous in Arabia, but the establishment of new dynasties coincided with the mid-ninth-century Sudanese ‘gold rush,’ which heightened the decline of Arabian mines and focused attention on those littering the border of Egypt and Nubia. The key African Red Sea ports of Sawākin, ʿAidhāb, and Bāḍiʿ, specifically, appear to have developed as a result of the gold trade, which was the primary reason for their overtaking of the ports of Antiquity (e.g., Power 2008; Breen 2013). Further south, from the eleventh century onwards, the Dahlak archipelago (north-east of Aksum, see figure 1) increasingly became an independent nexus for trade coming through the Red Sea from its Indian Ocean entrance (e.g., Margariti 2010). The Arabian ports, with the exception of Jiddah as the port of Mecca, were a shadow of their former selves by the time of the arrival of the Latin Europeans. Jiddah’s value, in particular, lay in accomodating pilgrims on the Ḥajj, rather than as a general commercial hub akin to ʿAidhāb, which would have proved of little economic interest to Latin Europeans. In addition, the African ports further prospered from the eleventh-century shift in Indian Ocean trade away from the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea following the arrival of the Fāṭimids in Egypt (969–1171) (Whitehouse 1983), with Chinese ceramics appearing throughout Egypt from the eleventh century via their importation through ʿAidhāb (Mikami 1988; Peacock and Peacock 2008). In addition to the archaeology, this shift is illustrated by the fact that the earliest known Genizah document pertaining to Indian trade in Egypt dates to 1097 (Goitein 1973, 177–81).

Alongside the African and Arabian Red Sea ports, there was also the significant Jordanian port of Aqaba. Excavations at Aqaba dating to the period before the Crusader States are suggestive of a port which adapted to various local and regional challenges (Damgaard 2009), which would suggest that any inhabitants would not necessarily have been dismissive of the Latin Europeans’ arrival, especially as the Latin Christians cemented their foothold along the Palestinian coast and its hinterlands after 1099. An earthquake in the year 1068 appears to have had a profound effect on the immediate productivity and activity of the port, however, exemplified by the fact that the majority of Chinese pottery shards found at Aqaba were found in the phase dated to between 950 and 1050 (Whitcomb 1994, 10). Nevertheless, no other ports gained enough prominance in the Gulf of Aqaba to suggest that they would have overtaken the temporarily fleeting Aqaba in importance. This would emphasise the plausibility that currently unexcavated adjacent sites facilitated Aqaba’s recovery following the earthquake, underlining the need for further excavations to fully assess Aqaba’s activity during this period.1 Overall, Latin Europeans were arriving to a new era of Red Sea trade at the turn of the twelfth century, which had become centred on the connectivity of its African coast. That said, current evidence suggests that the Latin Europeans were only engaged within the northern half of the Red Sea, epitomised by subsequent discussions centring on ʿAidhāb, and there are no signs that events in the southern half, such as concerning the Dahlak Islands, were either known or at least noted by them. This contrasting engagement with the northern and southern portions of the Red Sea would certainly explain why the Latin Europeans’ initial growth in knowledge concerned Nubia rather than Ethiopia.

The Red Sea Avenues of Knowledge Exchange during the Twelfth Century

With the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Latin Christians were not necessarily mere recipients of the Red Sea networks of exchange of the previous centuries either. The lack of evidence which would shed light on Latin European engagement with the Red Sea is likely due to the limited nature of twelfth-century sources more generally. Nevertheless, the Latin European occupation at Ile de Graye before its capture by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn in 1170/1171 deserves further enquiry. Excavations carried out between 1975 and 1981 uncovered about 1500 textile fragments from the island, which, based on accompanying ceramics and Carbon-14 analysis, dated from between the late twelfth century and the beginning of the fourteenth century, thus possibly dating from the latter end of Latin European rule of the island. The textiles included cotton, linen, felt, woollen fabric, goat hair fabric, and a few silk fragments. Whilst the dating of the textiles cannot be further deduced, the textiles may, as noted by Adrian Boas, give an indication of the contemporary textile trade passing through the island, to which Latin Europeans would have similarly contributed (2017, 187–88). Likewise, to date, no analysis has been undertaken on the only ivory object known to have been produced in the Crusader States—the twelfth-century Melisende Psalter—to uncover its material origin. If such work was allowed, the results might indicate the potential source for the ivory, possibly highlighting Red Sea connectivity.

Similar deductions may also be made from the numismatic evidence. Analysis by Ronald Messier has shown a distinction between Fāṭimid coins which show consistencies with West African gold dating prior to the Fāṭimid loss of North Africa in 1047, with a new gold source dominating after this—the ʿAllaqī gold mines of the Nubian desert, situated between the Nile and the Red Sea. However, Messier further argued that the post-1047 Nubian supply did not necessarily prove sufficient for demand and ultimately led to the gold crisis during the early years of Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn (1974), though this has been challenged by Amar Baadj, who has pointed towards Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn’s aggressive policy towards Nubia, which disrupted Nubia’s importance as a major source of Egypt‘s gold and caused the crisis (2014). In any case, in contrast, little analysis of the gold of Crusader coins has been undertaken which would indicate their possible Nubian origin from these same mines. That said, it would be expected to find at least some Crusader coins minted from gold from either Nubia or East Africa, as well as Syria. For example, it has been pointed out that the fineness of the gold coins of the Crusader States corelated with those of Fāṭimid Egypt prior to the fineness reductions of the 1170s and 1180s, before decreasing yet again after 1187 (Gordus and Metcalf 1980; Metcalf 2000). Further study into this trade may not reveal Latin European interaction with Red Sea trade directly, but rather via Fāṭimid and Ayyūbid mediaries, but it would certainly paint a picture of the trade networks that the Latin Europeans were active in. The correlation between the fineness of Crusader and Fāṭimid/Ayyūbid coins would suggest that Latin Europeans were engaged in the wider Red Sea gold trade either directly or indirectly.

It is also likely that the Latin Europeans had some role in other prosperous trades, such as the glass bead trade, given their position at the crossroads; beads dating to this period and manufactured in Syria and Palestine, as well as further east, in Iraq and Iran, have been found as far as West Africa and it would appear likely that such beads may have passed through the Crusader States prior to their final destination (e.g., McIntosh et al. 2020). Certainly, the scope of the Red Sea trade was not alien to Latin Christian writers. For example, the German pilgrim Thietmar specifically noted, whilst on pilgrimage in the early thirteenth century, how Indian ships frequently sailed through the Red Sea to Egypt before transporting their merchandise to the Nile for selling (Et veniunt frequenter Indi navibus suis per mare rubrum in […] Egyptum, per […] Nilum, sua mercimonia transportantes) (Koppitz 2011, 162). The Indian trade between ʿAidhāb and Alexandria was also mentioned in the Old French continuation of William of Tyre, one of a number of thirteenth-century continuations of the chronicle of the most prominent historian in the twelfth-century Kingdom of Jerusalem, William of Tyre (died 1185) (Paris 1879–1880, II:298–299). The twelfth-century Red Sea Indian trade and its conduct through ʿAidhāb is reflected in multiple Genizah documents, further highlighting the significance of the port’s references in Latin Christian texts. One document in question dates to 1140–1141 and speaks of an Indian representative for the trade in ʿAidhāb (Goitein 1967–1993, I:269). This particular example importantly stresses the scope of Indian trade in the Red Sea region precisely during the period of limited Fāṭimid oversight on the trade prior to their increasing focus in the second half of the century, thus seemingly enabling optimal circumstances for Latin European participation without too much regional reprieve if they so wished. Despite the current limited direct evidence, it is arguable that the twelfth-century Crusader States would have found it more difficult to avoid participation in Red Sea trade in some capacity than to have exploited their regional position adjacent to the sea.

In addition to material goods, the role of slavery throughout the Red Sea region cannot be understated, either. Nubians, especially, played a major role regarding the size and capabilities of the Muslim armies, until Nubian cohorts were increasingly replaced by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn in the 1170s (Lev 1999, 141–57). African soldiers were particularly integral to the Fāṭimid armies, much more than they had been in previous dynasties (Bacharach 1981; Zouache 2019). African military diasporas would have been present throughout the wider Red Sea region and the Holy Land, both those individuals in active service and those who had retired to live a post-military life. Early crusading Latin Europeans made note of African soldiers in the Muslim armies, an unknown number of whom would have been captured, such as the unspecified captives taken at Ascalon by the Latin Europeans during the First Crusade (e.g., Albert of Aachen 2007, 678), though these writers did not divulge any further information on non- or post-military African diasporas (e.g., Fulcheri Cartonensis 1913, 300–301, 308–9, 311–12, 414, 489–90, 498–500, 503, 661–63). The Crusader States were not known for employing manual slave labour, but domestic slaves were certainly present. Whether enslaved, manumitted, or retired, Africans were possible vessels of knowledge. In comparison, captured Latin Christians were similarly known to have been sold in the slave markets of Egypt, and the German pilgrim Thietmar witnessed captured French, English, and Latin Christians at Ile de Graye, which was then in Muslim hands, during his pilgrimage in 1217/1218 (Koppitz 2011, 162). It would not be unreasonable to suggest that some of the captured Latin Christians would have been sold southward into the markets of the Red Sea, similarly acting as informants within African communities, though there is no comparable documented evidence of their effects on African knowledge.

The consequences of the position that Latin Europeans found themselves in in the Holy Land should not be underestimated either, especially if we accept Ronnie Ellenblum’s hypothesis that the Latin Europeans only made up between 15 and 25% of the population of the Crusader States on average (2002). Indeed, the primary narrative of Latin Christian intolerance of other groups continues to be challenged (e.g., Mourad 2020). Such a small sub-population, which appears to have been largely centred in urban areas, would have necessitated interactions with other Eastern groups, both locally and regionally, including with Nubians and Ethiopians. No sources attest to the position of Africans within Crusader State society, but it should be noted that multiple people with the surname “Niger” are found in twelfth-century documents from the Kingdom of Jerusalem, notably as witnesses (Röhricht 1904, 59–60, 62, 69, 72, 79, 86, 88, 96, 97, 103–4, 113, 128, 132–33, 148, 213–14, supplementum 23-24), but also as donors of land, as was the case of Adam Niger in 1163 (Röhricht 1904, 103–4).2 This includes a later, otherwise-unknown Guido de Nubie in the 1220s and 1240s (Mayer and Richard 2010, III:1075, 1092, 1099, 1200). Whilst these names can be alternatively explained—for example, those with “Black” as a surname could have been any darker-skinned person or someone whose named originated from a profession, such as cloth dying, or a location, such as the Black Mountains—the documented potential presence of Africans within Crusader State society needs to be highlighted and not automatically rejected. Notwithstanding other motivations or circumstances, such as trade or slavery and subsequent manumission, Christian Nubians and Ethiopians had the attraction of Jerusalem and other Christian locations to encourage permanent migration to religious sites throughout the Holy Land to account for these possible documented Africans who did not appear as segregated within Crusader State society. Conversions between different Christianities, if indeed these people were Latin Christian, would have been a less radical undertaking for a Christian Nubian or Ethiopian than for a formerly Muslim or polytheistic captive. Both local and regional interactions built upon other direct experiences of Latin Europeans to inform them of their neighbours and their environment, which can be evidenced through early Latin Christian discussions of Nubia and Ethiopia. Prior to the First Crusade, surviving Latin Christian sources show no awareness of contemporary events in either Nubia or Ethiopia since the seventh century, highlighting the importance of twelfth-century Holy Land and wider Red Sea interaction, which reflected the prosperous situation during Antiquity.

Nubians and Ethiopians in Latin European-African Red Sea Twelfth-Century Networks

In comparison to the Latin Christian sources, African sources detailing African twelfth-century Red Sea and Holy Land engagement are more scarce. For instance, few contemporary documents survive to reconstruct a consistent national history of Ethiopia under the Zagwe dynasty (tenth century?–1270), let alone to provide consistent evidence for wider regional contacts during the twelfth century, whilst Nubian sources are overwhelmingly focused on internal economic or religious matters (e.g., Derat 2018; Ruffini 2012). That is to say that their respective internal sources are less direct on matters concerning international affairs. For instance, no twelfth-century chronicles or other historical works have survived from either Nubia or Ethiopia. Nevertheless, the presence of Nubians and Ethiopians within networks similar to those which Latin Europeans inhabited, both in Red Sea trade and throughout Holy Land pilgrimage routes, can be postulated. In the case of Nubia, its description as a “Mediterranean society” by Giovanni Ruffini should be further expanded (2012) and its place within a “Red Sea society” should not be overlooked, either. The same applies to Ethiopia.3

The Holy Land

Latin Christian sources largely discuss Nubians and Ethiopians in the Holy Land only towards the turn of the thirteenth century, most likely reflecting a larger transformation in Latin Christian pilgrimage discourse toward focusing on the pilgrims’ complete experience rather than solely on urban geography, notably Jerusalem (Wilkinson et al. 1988, 78–84). Even so, surviving Latin Christian pilgrimage texts which note the presence of Africans in the Holy Land during this period primarily date from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Nevertheless, significantly, as highlighted by Camille Rouxpetel, such accounts by Latin Christian pilgrims increasingly described these Africans based on experience, despite some occasional confusions (Rouxpetel 2012, 2015, 104–6, 115–36). Retracing the Nubian and Ethiopian presence in the Holy Land should not merely focus on physical presence but should also situate it within activities which are largely ignored in pilgrimage texts until the fourteenth century. For instance, the earliest surviving reference to Latin Europeans worshipping alongside Nubini outside the Holy Sepulchre during Holy Saturday after the hour of the Vespers only occurs in the mid-fourteenth century, when this was witnessed by the Tuscan Franciscan Niccolò da Poggibonsi whilst on pilgrimage to Jerusalem between the years 1345 and 1350 (1968, I:103–104). Yet it would be highly unlikely that such shared acts of worship at key shrines had not similarly occurred in the previous centuries despite the lack of evidence of the fact. The presence of any group amongst others was not static, and resulted in multi-layered interactions, not just on the macro level but also on the often more elusive micro level.

Explorations of the question regarding the African presence in the Holy Land of the twelfth century are particularly hindered by the lack of Nubian or Ethiopian contemporary sources on the matter. As far as Latin Christians were concerned, Nubians were only recorded at Jerusalem from 1172 (Huygens 1994, 152). A twelfth-century Ethiopian presence, however, has largely centred on their first appearance being owed to a supposed donation of churches to the Ethiopians by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn following his recapture of Jerusalem in 1187 (e.g., Cerulli 1943, 1:31–37; van Donzel 1999). This debate rests almost solely on an unreferenced statement by Athanasios Papadopoulos-Kerameus, a Greek scholar researching in the library of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem in the 1890s, though it is unknown whether he based his claim on the authority of a manuscript he had found in the archives or not (Papadopoulos-Kerameus 1891–1898, II:409). Emery van Donzel has correctly labelled Papadopoulos-Kerameus’ statement as fake, despite also highlighting an earlier 1573 text by Stefano Lusignano, which attests to Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn making this donation in passing; yet van Donzel remained assertive that there is no evidence for Ethiopians in Jerusalem in 1187, or indeed prior to the thirteenth century (1999). From an Ethiopian perspective, Sergew Hable Sellassie also pointed to the Gadl Yemreḥanna Krestos to note the absence of Ethiopians during the early twelfth-century reign of Yemreḥanna Krestos, although the earliest text dates to the late fifteenth century and, as Marie-Laure Derat notes, should be read in a Solomonic, rather than twelfth-century, context (Sergew Hable Sellassie 1972, 261; Derat 2010, 174–81). As a result of the lack of evidence of an Ethiopian presence in historical sources, twelfth-century knowledge of Ethiopia has been depicted as practically non-existent (e.g., Hamilton 2006). However, surviving Latin Christian textual records from the twelfth century suggest that their respective authors knew and experienced less of these wider Red Sea diasporas than was actually the case.

The toponymy of churches in Ethiopia simulates those of the Holy Land, not least the building of Lalibäla’s (reigned from before 1204 to after 1225) New Jerusalem, reportedly following a visit to the city in a dream (Perruchon 1892, 22–25, 37–40, 55–61). The construction of this New Jerusalem at the location now known as Roḥa (noticeably reflecting a close similarity to the Arabic toponym for Edessa, al-Ruhā) has been noted for both its religious and political importance (e.g., Heldman 1992, 229–32; Phillipson 2014, 237–38; Derat 2018, 163–73, 182–90), yet it has not been widely discussed in relation to Ethiopian pilgrimages. The churches at Roḥa emulate key pilgrimage centres in the Holy Land, such as Golgotha in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Mount Sinai, and can be seen to offer destinations for Ethiopians to undertake surrogate pilgrimages to the Holy Land whilst remaining within Ethiopia for either economic or political reasons, following many contemporary examples from across the Christian world (Derat 2018, 185–86). As such, surrogate pilgrimages would suggest a keen interest by Ethiopians to visit the Holy Land, thus reflecting a longer history of Ethiopian Red Sea-Holy Land interconnectivity, which has yet to be revealed in its scope by the surviving textual and archaeological record. Indeed, a twelfth-century manuscript from Rouen has been suggested by Anton Schall to attest to an Ethiopian presence pre-dating the supposed donation by Saladin, too (1986). The manuscript in question is a liturgical drama which has been suggested to include a Latin transliteration of some Gəʿəz words for a three-line passage spoken by the magi, as understood by the Latin author, thus needing at least one Ethiopian speaker as its source.4 Extrapolating from that, Schall further argued that an Ethiopian twelfth-century presence in Jerusalem could have acted as mediators for such cultural exchange despite the limited evidence for such a presence (Schall 1986). However, Ethiopian textual evidence to attest to Roḥa’s explicit replication of Holy Land sites, despite the churches being built and developed in phases across multiple earlier centuries, only dates from the fifteenth century, such as regarding the church of Golgotha (Derat 2018, 188–90). Therefore, despite earlier evidence for the churches’ construction, their association with the Holy Land may post-date Lalibäla’s reign, which would limit any ability to view the churches as purposefully built surrogate pilgrimage destinations for an Ethiopian populace which frequented Jerusalem and the Holy Land more widely. Nevertheless, the limited direct evidence from all sides should not necessarily be viewed as proof for a lack of Ethiopian engagement with the twelfth-century Holy Land as a pilgrimage destination.

Furthermore, an active Nubian presence in the twelfth-century Holy Land is also supported by, albeit circumstantial, evidence of Nubian knowledge of Syriac. A twelfth-century Syriac alphabet has been found at Qasr Ibrim in Lower Nubia, whilst Ibn al-Nadīm noted the Nubian knowledge of Syriac earlier in the tenth century (van Ginkel and van der Vliet 2015; Ibn al-Nadim 1871–1872, I:19). This is particularly notable for reconstructing Nubian message networks, as no Syriac works have been found in Nubia to date (Ochała 2014, 26–27), which suggests that the language was used for communication, not for translation projects. Similarly, Hetʾum of Corycus suggested in the early fourteenth century that Armenians could act as interlocuters between Latin Europeans and Nubians, suggesting an established network of communication (Hetʾum of Corycus 1906, 247). Hetʾum’s statement may well have been rhetorical, but if Armenians, along with Syrians, did indeed communicate with Nubians, messengers would have certainly utilised Red Sea routes as well as those of the Nile. Indeed, Bernard Hamilton noted how it was perhaps not coincidental, for example, that Latin Christian knowledge of Nubia developed following the visit of the Syrian patriarch Michael Rabo (reigned 1166–1199), whom the messengers would have been communicating with, to Jerusalem in 1168, following King Amalric’s request (Hamilton 2014, 172). Certainly, Amalric displayed knowledge of Nubia’s subordination to the Coptic patriarch no later than 1173, which may have come as a result of Michael’s visit, if not by contacts with Nubians in the Kingdom of Jerusalem directly (Röhricht 1904, 131–32). Whilst Michael’s short visit could not have provided the entire foundation for the growing development of Latin Christian knowledge, the exchange provides a succinct anecdote which portrays the intellectual importance of inter-cultural engagements. Moreover, such Nubian messengers, along with pilgrims, traders, and other travellers, may have accounted for the Nubians (Kūšāyē) and Ethiopians (Hindāyē)5 who were insinuated by Michael Rabo to have been present in Syria, Palestine, Armenia, and Egypt in the late 1120s, where they were occasionally provoked, along with other Monophysites, by Greeks (Michael the Syrian 1899–1910, IV:608). It is unclear from Michael’s text whether he intended to localise Nubians and Ethiopians specifically in Egypt or if they were also to be associated with the other lands mentioned. If we take a positivist approach, this reference pre-dates any Latin European acknowledgement of either Nubians or Ethiopians in these lands by at least five decades.

The Red Sea

Specifically regarding twelfth-century African pilgrims, in the case of the northern Red Sea port of Aqaba, tentative evidence suggests at least an Ethiopian use of the port for pilgrimages to the Holy Land. The many Aqaba amphorae which have been found throughout Aksumite sites are testaments to an historic trade network throughout the first millennium. Two Aksumite copper coins, the first likely dated to the late fourth or early fifth century, based on similar coins, and the other dating to the late seventh or early eighth century, further suggest that such connections went beyond trade, as such low-value coins would have been more important for poorer pilgrims than traders (Whitcomb 1994, 16–17). An Ethiopian inscription left by one ʾAgaton, a monk who appears to have travelled from the otherwise unknown monastery of Däbrä Manz(?), found in the Wādī Ḥajjaj in eastern Sinai, has been dated to before the seventh century (though it might be much younger, given the difficulties in dating inscriptions) and further attests to an historic pilgrimage route via the peninsula which seemingly operated through Aqaba (Puech 1980). Whilst the Ethiopian pilgrimage route via Aqaba is seldom attested in textual sources until later centuries, it would appear likely that it survived the fall of Aksum. Pilgrimage was certainly not upended. One eleventh- or early twelfth-century inscription found in the Wādī al-Naṭrūn, located between Alexandria and Cairo, seemingly attests to eleven Ethiopian pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem who had originally followed a route along the Nile; the text is fragmentary and does not mention Jerusalem by name, but it speaks of the Ethiopians arriving after two of their party had died on the way, indicating they were on a journey with the likely intention to carry on towards Jerusalem (Conti Rossini 1922, 461–62). Most recently, Samantha Kelly has taken a positivist outlook on the existence of Ethiopian material at the monastery of St. Anthony on the Red Sea and at Sinai, some of which date to the twelfth century, such as the twelfth- or thirteenth-century Greek palimpsest at St Catherine’s monastery with a Gəʿəz subscript6 or a similarly dated fragment of an Ethiopian manuscript found at the monastery of St. Anthony (El-Antony, Blid, and Butts 2015), to argue for the continued use of the Red Sea route to Jerusalem during this period (Kelly 2020, 428–29), in the absence of other direct evidence.

Later Ethiopian informants certainly revealed to the Venetian Alessandro Zorzi in the early sixteenth century that pilgrims travelled to the Holy Land using a sea route between the Sudanese port of Sawākin and Sinai. Zorzi does not name Aqaba directly, instead describing the Sinai location as a “castle by the sea” (castel a marina) named Coser, seemingly reflecting an understanding of the generic Arabic or Gəʿəz qaṣr/qəṣr, “fortress” (Crawford 1958, 126–29). The continued post-Aksumite population density of northeastern Təgray, which is almost six times greater than that of western Təgray, further inland, has also been assumed as due to maintaining maritime connections (D’Andrea et al. 2008). Problematically, current archaeology of Aqaba suggests an absence of sustained material for a developed or fortified presence at the site between the 1068 earthquake and the appearance of a fortified “khan” in the late thirteenth- or early fourteenth-century Mamluk period (Whitcomb 1994; Al-Shquor 2008). Nevertheless, any Latin Christians at Ile de Graye would have likely interacted with travelling Ethiopian pilgrims who would have disembarked at Aqaba. Evidence for a Nubian route via Aqaba, on the other hand, can only be presumed based on the importance of Aqaba as a connecting port. Nubian pilgrims travelled to the Holy Land via the Nile and Egypt or via the Red Sea; the latter route can only be reconstructed based on knowledge of Red Sea ports and connectivity, such as the Nubian relationship with ʿAidhāb, as no direct Nubian evidence accounting for such pilgrimage activity is currently known. Nevertheless, contemporary Nubian pilgrimage activity elsewhere certainly increased in scope, such as in Lower Nubia from the eleventh century, when new rooms, including a kitchen and a bakery, were added to the monastery of Apa Dioscorus (Obłuski 2019, 18–19, 132, 183), suggesting a sizable Nubian interest in undertaking pilgrimage more broadly, which may be extrapolated to the Holy Land.

Whilst Sawākin appears to have been the primary embarking Red Sea port for Ethiopian pilgrims, it is unknown which Red Sea port was the primary port for travelling Nubian pilgrims. That said, evidence points towards ʿAidhāb, the Red Sea port directly east of the important Nubian Nilotic settlement of Qasr Ibrim, the subjecting jurisdiction of which—whether Egyptian, Nubian, or quasi-independent (see below)—is not always clear. No contemporary texts refer directly to the Christian pilgrim traffic through ʿAidhāb, but many operators existed at the port to faciltate Muslims undertaking the Ḥajj to Mecca. The greed of these pilgrim crossing operators, who packed Muslim pilgrims onto their boats like “chickens in cages” (aqfāṣ al-dajāj al-mamlūʾa), as described by Ibn Jubayr in 1183, would suggest that they would not have ignored the opportunity to make money from accomodating African Christians travelling north, too (Ibn Jubayr 1964, 65). Certainly, ʿAidhāb and Nubia were connected during this period. Fāṭimid officials are known to have traded with Nubia through ʿAidhāb, for example (Plumley 1975, 106). Additionally, the continuation of William of Tyre described traders from the two “Ethiopias” (Ethiopes), likely including Nubians, trading in pepper (poivre), spices (espices), ointments (oignemenz), electuaries (lectuaires), precious stones (pierres precieuses), silks (dras de soie), and other many things (pluseurs choses) from ʿAidhāb in Alexandria (Paris 1879–1880, II:298–299). Our knowledge of the relationship between Nubia and ʿAidhāb is otherwise limited, yet the port remained significant enough within Nubia’s sphere of influence for King David to sack the port in 1272 as well as for later commentators to note that many inhabitants of ʿAidhāb fled to the Nubian capital at Dongola after it was attacked by the Mamluk sultan Barsbay in 1426 (Ramusio 1550, 87a). Although evidence remains limited for the twelfth century, this relationship between Nubia and ʿAidhāb, as will be discussed below, may be of particular importance for burgeoning Latin European-Nubian engagement during this century.

Egypt

Beyond the Holy Land, Egypt cannot be underestimated for its role as an arena of exchange between Africans and Latin Christians either, particularly given its significant location along the Red Sea. Again, contemporary twelfth-century evidence is scare, yet a picture can be painted. Prior to the Crusades, Egypt was said to have been receiving so many messengers from Nubia and Ethiopia that the Coptic patriarch Pope St. Christodoulos (reigned 1046–1077) moved the Coptic See from Alexandria to Cairo in order facilitate an easier reception of these many messengers (History of the Patriarchs 1943–1974, III.II:327–28). Lower Egypt, especially, was an area with a strong African presence. For example, Nubian and Ethiopian objects from the Wādī al-Naṭrūn, such as a white marble tray with Greek and Old Nubian inscriptions, including the name of the Nubian King Georgios IV (reigned 1131–1158), and a contemporary polyglot manuscript of Epistles containing Armenian, Arabic, Coptic, Syriac, and Gəʿəz, attest to their presence there (Bishop Martyros 2013; Evelyn White and G 1972, II:366, 368). Additionally, Africans were recorded in Alexandria throughout the twelfth century, with Benjamin of Tudela witnessing people from Ḥabaš, whilst the continuation of William of Tyre had been informed by traders from the two “Ethiopias,” as noted above (Benjamin of Tudela 1907, 106; Paris 1879–1880, II:298–99).

Latin Christian texts do not divulge much information on Latin European Crusader activity in Egypt during the twelfth century besides trade with Alexandria and the notable five expeditions led by King Amalric of Jerusalem during the 1160s. For instance, neither the accounts of Hugh of Caesarea’s (1167) nor Burchard of Strasbourg’s (1175) embassies to Cairo make note of any interactions with Christian Nubians or Ethiopians. Nevertheless, there is evidence that Cairo, especially, may have been an important undocumented place of exchange. Despite the absence in Latin Christian texts, it is notable that the contemporary account of Abū al-Makārim describes envoys of the Greeks (Rūm), Franks (Faranğ), Ethiopians (Ḥabaša), and Nubians (Nūbah) all worshipping customarily alongside each other at the fountain of al-Maṭariyya in Cairo during their stays (Abū al-Makārim 1984, I:24). Further evidence is suggestive of interactions, notably the appearance of the word santa in an Old Nubian text found at Qasr Ibrim, which possibly dates to the late twelfth century, written to santa Maria and santa Simeon seemingly requesting some form of help. The striking use of santa for “saint,” instead of the usual Old Nubian forms of either agios or ngiss, was first recently noted by Giovanni Ruffini, who specifically highlighted the Italian influence, which is indicative of otherwise unknown interaction that was sustained long enough to facilitate language transfer (2012, 262–63). Importantly, both Africans and Latin Europeans shared multiple arenas of interaction, both those recorded and many more that were not.

With an Ethiopian and Nubian presence in the wider Holy Land and Egypt established, further questions regarding exchanges come to light; for example, with no evidence of settled African communities at the Holy Sepulchre during the twelfth century,7 where did pilgrims stay? Did they frequent hostels connected to the major sites run by resident Nubian or Ethiopian monks, as can be witnessed in pilgrimage centres within Nubia (Obłuski 2019) and gleaned from later reference to the role of the mäggabi, in some Ethiopian monasteries, as a ‘provisioner,’ such as in Jerusalem, Qusqam, and in the Wādī al-Naṭrūn (Kelly 2020, 432–33)? Or did they stay in accommodations operated by anybody who wished to do business on the bustling pilgrimage trade? Regrettably, no evidence is currently available to answer these questions for the international pilgrimage centres of the twelfth century. Certainly, language would hardly have been a barrier for pilgrims. Besides the possibility of independent language learning and African-run hostels, Arabic was a readily applicable lingua franca for both groups to navigate the Holy Land.8 That is not to dismiss the possible roles of Syriac and Armenian as communicative languages, highlighted above, or even Coptic (e.g., Aslanov 2002), either. On a practical note, later sources attest to word lists used to navigate multi-lingual communities within Latin Europe (Durseteler 2012), and even those used by Latin European travellers to early fiftteenth-century Ethiopia (Jorga 1910), though contemporary, or near-contemporary, evidence for the reverse is lacking, with a notable exception of a thirteenth-century Copto-Arabic Old French word list copied in a later sixteenth-century text (Aslanov 2006), which may illustrate similar means of communication used earlier. At the very least, the ability to communicate via signs and gestures was universal, and such activity could develop its own subject-specific lexicons (e.g., Bragg 1997); in this case, a lexicon for pilgrimage. Whatever the case, a journey could not feasibly have been undertaken from either Nubia or Ethiopia without a permanent or semi-permanent infrastructure maintained by African diasporas and connected centres. Furthermore, if Adam Niger was of African descent, his donation of land to the Hospitallers in 1163 begs the question of how the level of integration of Africans in the Crusader States (Röhricht 1904, 103–4) and, thus, who had the means to offer a service of accommodation and sustenance. Moreover, such possible settled African diasporas pose further questions regarding their influence at court, especially as owners of land, as witnesses to importance documents, and as potential maintainers of a hostel network (whether such influence transpired into the development of knowledge or not).

(Re)Tracing the Evidence for the Development of Knowledge on the Red Sea

Despite the “regime of silence” in Latin European texts—as termed by Christopher MacEvitt (2008)—regarding the local populations of the Crusader States, evidence of exchange can still be constructed via alternative, or indirect, readings of the available sources. For example, texts may not always directly comment on physical interactions, but some may note a toponym in passing which clearly must have been the result of the text’s author being informed by someone with a specific set of linguistic or cultural knowledge. There are multiple illustrative examples of such networks in the twelfth-century Holy Land and the wider region which may have informed Latin Christian knowledge of Nubians and Ethiopians. One named example is a man from Aleppo called Masʾūd, who accompanied an envoy to Dongola on behalf of Tūrānšāh in 1172/1173, and who would have likely shared stories of his travels during his return home (Abū Šāma 1997, II:161–62; Barhebraei 1890, 346). Equally, many were informed by ‘communal knowledge,’ despite such knowledge largely being absent in the textual record. The application of ‘communal knowledge’ can be viewed as the antithesis of Brian Stock’s notion of “textual communities” (1983). Thus, instead of a community organising itself around a central text, or set of texts, ‘communal knowledge’ is the uncodified knowledge that informs non-textual communities. For instance, many more Latin Europeans would have known about the Nubian and Ethiopian practice of what Latin Christians called being “baptised by fire” branding crosses on their foreheads and cheeks, than the few Latin Christians who actually made a textual reference to this (the first of which only appear in the thirteenth century (Robert de Clari 2004, 130; Oliver von Paderborn 1894, 264; Jacques de Vitry 2008, 308; Koppitz 2011, 170)). Regrettably, the lack of comparable African evidence to speak to the reverse effects of these interactions on the Nubians and Ethiopians means that this cannot be discussed any further, but it should be maintained that knowledge development was not solely the result of a single transfer.

So what can be said about the role of the Red Sea in the twelfth-century development of Latin European geographical knowledge? Latin authors based in the Holy Land were undoubtedly influenced by their regional sources. For example, William of Tyre used the toponym of Cahere when referring to Cairo, a clear Latinisation of the Arabic toponym al-Qāhira, in his Historia Rerum in Partibus Transmarinis Gestarum (written 1170–1184) (e.g., William of Tyre and Huygens 1986, II:896–97). William was also the first Latin Christian writer based in the Holy Land to show direct knowledge of ʿAidhāb, despite not venturing into the Red Sea directly himself (William of Tyre and Huygens 1986, II:903). It is unlikely that he was the first Latin Christian writer to actually know about ʿAidhāb, but earlier evidence is lacking. ʿAidhāb was also noted by Latin Christians who were said to have travelled to the Red Sea port. The text attributed to Robert of Howden, which dates to some time in the second half of the twelfth century, documents his journey to the “great city” (civitatem magnam) of ʿAidhāb (Aideb), which took camel caravans (mercatores cum camelis) 18 days to commute to from the trade hub at Qūṣ (Coso) on the Nile (Gautier-Dalché 1995, 215–16). Increasing references to ʿAidhāb reflect the developing Latin Christian understanding of the Red Sea in the late twelfth century, which attests to at least some Latin European participation in Red Sea trade, both directly and indirectly. Most of all, knowledge was not exclusive to only those who were actively present in the Red Sea region themselves.

Distinguishing Ethiopia from Nubia as a Result of (Un)Documented Networks

Whilst few twelfth-century Latin European sources note exchanges with Africans, it is clear that Latin authors had access to sources which informed them about Nubia and Ethiopia. Although ‘Ethiopia’ continued to be used as a common toponym, the incorporation of the toponym of Nubia emerged alongside that of ‘Abyssinia.’ Such increasing understanding of these toponyms further suggests a development in specific geographical knowledge of northeast Africa as a result of the Crusades, a conclusion also reached by Robin Seignobos and Bernard Hamilton (Seignobos 2012; Hamilton 2014). ‘Abyssinia,’ especially, is a clear example of the phenomenon of regional knowledge informing Latin Christians in the late-twelfth century, as it reflects the accumulation of knowledge about the land of Ḥabaš[a] (Ethiopia in Arabic and Hebrew) or Ḥabašat (Ethiopia in Gəʿəz), which had no earlier Latin Christian geographical discourse to otherwise act as a source for copying. The first surviving attestation to this appears in the text attributed to Roger of Howden, which briefly detailed the land of Abitis, which was ruled by a “king John” (rex Johannes), who was at war with the ruler of Aden (Melec Sanar) (Gautier-Dalché 1995, 216–17). The kingdom was said to take eight months to traverse and has been highlighted by Patrick Gautier-Dalché to have been an amalgamation of multiple Asian and African polities (1995, 281), suggesting that Roger was unlikely to have travelled directly to Ethiopia whilst in the Red Sea region. Nevertheless, the reference to “king John” would appear to be an understanding of the Gəʿəz salutation regarding the Ethiopian ruler, ğan (“majesty”), which has been argued by Constantin Marinescu to have been the origin of the name Prester John via an Italian misinterpretation of the phrase referring to the personal name Gian/Zane (“John”), thus requiring direct contact with Ethiopians (1923, 101–3). Equally, the earliest known appearance of the Ḥabaš-influenced toponym of Abitis found within this text also reflects the twelfth-century inter-linguistic and inter-cultural interactions and knowledge dissemination regarding the Red Sea region. Given that direct engagement with Ethiopians explains the appearance of a “king John” in the text, it would also be reasonable to assume that Abitis was similarly influenced by the Gəʿəz toponym Ḥabašat, likely from the same informers as the “king John” reference, rather than from Arabic- or Hebrew-speaking informers of Ḥabaš[a]; it at least underlines that ‘Abyssinia’’s supposed Arabic origin should not be so readily concluded.

Simultaneously to the documenting of Abitis, a place called Abasitarum was documented in Africa by Gervase of Tilbury (flourished 1211–1215). This reference is included as a possible contemporary text because Gervase claims that he first conceived of his Otia Imperialia, which was written for Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV, thirty years previously during the reign of Otto’s uncle King Henry the Younger of England (died 1183). In this case, it may be that ‘Abyssinia’ had been known independently to, or even before, Roger of Howden (Gervase of Tilbury 2002, 14–15, 180–81). However, this may have been coincidental, as Gervase was copying from Orosius, who described the same region as Auasitarum (1889, 5). As Orosius was referring to the Oasitae (“oasis-dwellers”) of the Sahara—Orosius was not alone in his spelling of the ethnonym, which was based on the Coptic spelling for “oasis” (ouahe) (e.g., Strabo and Jones 1917–1932, I:500; Billerbeck and ed. 2006–2017, I:302)—it is possible that, despite Gervase’s preference for the wonderous, Gervase’s use was a conscious replacing of one toponym with another, identically spelt toponym—‘Abyssinia’—to reflect the most contemporary toponyms he had heard about concerning northeast Africa. Gervase may have been intending to ‘correct’ the passage. Whatever the case, Gervase’s example does not detract from contemporary Latin Christian burgeoning knowledge of ‘Abyssinia.’ Elsewhere, another instance of the appearance of the toponym can be found in the work of Ralph of Diceto (died circa 1202), which is the earliest surviving example of the repeated trope of Abesiam as one of Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn’s four brothers, along with Nubiam, Leemen (Yemen), and Mauros (Libya/North Africa?) (Stubbs 1876, II:82), representing Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn’s far-reaching conquests of neighbouring lands, although no expedition was ever launched against Ethiopia. Ralph’s text is significant here not because of the trope specifically, as this did not prove to be widespread and was largely limited to later texts chronicling the late twelfth century through copying (e.g., Roger of Wendover 1886–1889, I:146, 179; Matthew Paris 1872–1883, II:332, 361), but as further evidence for the growing acknowledgement of the toponym of ‘Abyssinia,’ which had a clear non-Latin origin.

Despite the discussion of ‘Abyssinia’ in the later twelfth century, Christian Ethiopians, or any notion of a Christian Ethiopia, for that matter, were only first noted by a Latin Christian author in the Holy Land in 1217–1218 (Koppitz 2011, 170). Nubia, on the other hand, experienced a more gradual insertion into Latin European geographical knowledge from the early twelfth century (e.g., Seignobos 2014). A contemporary Nubia first appears in Hugh of St. Victor’s Descriptio Mappe Mundi (written circa 1130), though only briefly as a kingdom below Egypt without any notice of its Christianity (Gautier-Dalché 1988, 147–48). Christian Nubians are first commented on in relation to the Christians who visited Santiago de Compostela in the Codex Calixtinus (written circa 1132–1158) (Whitehill 1944, I:148–149), with Christian Nubians being noted in Jerusalem in 1172 by the German pilgrim Theoderic (Huygens 1994, 152). The king of Nubia was known to Richard of Poitiers (died 1174) to have been at war with neighbouring ‘pagans’ in 1172 (Ricardi Pictaviensis 1882, 84). Who exactly Richard meant as these neighbouring pagans is unclear, but his text certainly portrays the king as a warrior maintaining the ‘Christian fight,’ and may, significantly, indicate an awareness of the Ayyūbid raid into Nubia led by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn’s brother Tūrānšāh in 1172/1173. Importantly, the earliest redaction of Richard’s text was started before 1156, which therefore presents the reference to Nubia in 1172 as a reflection of at least a sixteen-year writing and active development process. In his preface, Richard does not name any contemporary authors as his sources, but specifically notes as his influencers Isidore of Seville, Theodolfus, Josephus, Hegesippus, Eutropius, Titus Livy, Suetonius, Aimoinus, Justinus, Freculphus, Paulus Orosius, Anastasius, Anneus Florus, Gregory, Bede, Ado, Gildas, the monk Paul, and “a few others” (et quorumdam aliorum), none of whom would have provided him with the relevant Nubian knowledge that Richard detailed, not least because the majority of these authors wrote prior to Nubia’s official conversion in the mid-sixth century, let alone in more recent centuries or decades (Ricardi Pictaviensis 1882, 77). Perhaps the greatest illustration of the development of twelfth-century Latin Christian knowledge regarding Nubia occurs in the first and second Crusade cycles of chansons de geste. Within these songs we see that the twelfth-century so-called Old French ‘First Cycle’ depicts Nubian kings as Muslim allies and enemies of the Latin Europeans, before the thirteenth-century ‘Second Cycle’ begins to present the various Nubian kings as fellow Christians, often centring scenes of conversion and the kings’ Christian virtues to reflect the developing Latin Christian understanding of Nubia’s reality (Simmons 2019).

Renaud de Châtillon’s Red Sea ‘Raid’: A Likely Example of the Influence of Undocumented Networks on Latin European Knowledge?

Renaud de Châtillon’s Red Sea ‘raid’ of 1182–1183 may be one key event which needs to be viewed through a different lens as epitomising the influence of developing knowledge networks regarding both the Red Sea and, possibly, Nubia. Why the ‘raid’ occurred is disputed, as it is mostly known only through Muslim accounts, which paint Renaud in an overwhelmingly negative light because he was supposedly determined to attack Mecca. Renaud’s motivations were likely much more nuanced and multiple, however. As the former Prince of Antioch and the Lord of Oultrejordain at the time of the expedition, Renaud may have been jockeying for power during a time of internal weakness in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Alternatively, as has been noted by Carole Hillenbrand, since his release from captivity in Aleppo in 1176, Renaud had found a new zeal for the crusading cause and actively preyed upon Muslim caravans to disrupt Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn’s growing power (Hillenbrand 2003), suggesting that his Red Sea endeavour should not be viewed as an isolated event. Equally, the ‘raid’ may have reflected a wider defensive strategy and realpolitik which, in turn, fed Renaud’s personal desires (Mallett 2008). The overwhelming description of the event as a ‘raid’ in scholarship is the result of viewing the brief expedition in isolation of other factors. However, the attribution of the term ‘raid’ implies that it had no long-term strategic aim and was not the product of larger developments, not least those of an intellectual nature. Renaud was certainly politically astute, which would suggest that the Red Sea venture was not a wholly random and rogue event (e.g., Hamilton 2000, 159–85; Buck 2015). Whatever the true motive for Renaud’s expedition, it arguably reflects the Latin European utilisation of indigenous geographical knowledge of the Red Sea, along with their own experience, and was possibly also the product of early interest in the African Christian kingdoms of Nubia and Ethiopia.

The lack of Latin Christian evidence for the event appears to reflect its failure. Nevertheless, this has not stopped scholars from suggesting that the expedition may have been an exploratory fleet to learn more about the Red Sea, such as its winds, to directly access Indian Ocean trade (Prawer 1980, 482; Hamilton 2000, 68–69). Renaud and the expedition’s other planners were able to access multiple knowledge networks and, importantly, Renaud had already briefly held Aqaba in 1181, possibly to test the port’s defences prior to the full assault into the sea in 1182–1183 (Pringle 2005, 341–42). With such a small force, Renaud’s fleet must have had prior knowledge of the winds and currents of the Red Sea, or at least have had on-board navigators, to successfully enter out of the Gulf of Aqaba. It has been suggested that the expedition’s use of nailed boats, on account of the Latin Christians previously transporting them overland to Aqaba, indicates a lack of knowledge of the conditions of the Red Sea, as the water corrodes iron nails (which is why local boat builders made boats with sewn planks instead) (e.g., Margariti 2008, 567). However, boat construction does not reveal anything about the knowledge of the Latin Christians if the use of nailed boats was simply a matter of expedience and transportability. Moreover, at least one contemporary Latin Christian visitor to the Red Sea did indeed know that its boats were not fixed with sharp nails (non clavium clavis et acutis), though they state that this is so that the locals at ʿAidhāb can avoid damaging the diamonds (adamante), which were to be found on the shallow sea floor (lit: the sea “is not very deep,” non est valde profundum), when searching for them (Gautier-Dalché 2005, 216). The modern narrative of the expedition remains highly suggestive of a wandering fleet into the unknown, yet this was not the case.

Despite the limited evidence, such a narrative remains too simplistic. Renaud did not accompany his fleet—two boats of which blocked the former Crusader fortress at Ile de Graye, with three ships venturing onwards into the Red Sea—though it has been suggested that Renaud may have led a land blockade at Aqaba (e.g., Hamilton 2000, 182). Muslim sources explicitly mention that the fleet attacked ʿAidhāb. A motivation for this may have been to disrupt the general trade of the most significant port known to the Latin Christians, but it may also reflect a strategy for acquiring gold following the debasement of gold coins from the 1170s, as a gold crisis affected the economy as noted above. William of Tyre was certainly amongst contemporaries to note the importance of the gold trade to Egypt, and the aforementioned numismatic evidence would also suggest that the Latin Christians were well-aware of the gold crisis, which decreased the fineness of contemporary Crusader gold coins (William of Tyre and Huygens 1986, II:971; Gordus and Metcalf 1980). The Latin Christians certainly had a motive to attack important ports, rather than aimlessly causing havoc. Indeed, any Latin Christian involvement in the Red Sea would likely have fostered knowledge of the African coast, as it was widely known that the Arabian shoals were much more difficult to navigate, thus making ʿAidhāb a premeditated and more easily navigable target (Tibbetts 1961, 325). It is also notable that Latin Christian writers show no knowledge of other Red Sea or Indian Ocean African ports, such as Sawākin or Sofala, during this same period, further suggesting specific knowledge on the importance of ʿAidhāb. Latin Christians had been learning about the sea throughout the century and were fully aware of the importance of ʿAidhāb as a primary Red Sea hub of trade (e.g., Fulcheri Cartonensis 1913, 597; William of Tyre and Huygens 1986, II :903), with the text attributed to Roger of Howden stating that “great ships are loaded there [destined] for Greater India” (naves magne que in Indiam superiorem pergunt onerantur) (Gautier-Dalché 2005, 216). That said, there is one key issue with the descriptions of the Latin Christian attack on ʿAidhāb. Exploratory fieldwork by David and Andrew Peacock has suggested that ʿAidhāb had no viable port other than at Halaib, 20 km to its south (2008). As the Muslim writers who mentioned the attack on ʿAidhāb do not distinguish between the port and the town, it remains unclear where the Latin fleet actually attacked, but the choice of ʿAidhāb appears significant.

Without reading too much into the little available evidence, it may even be possible that ʿAidhāb was not initially the target of Renaud’s fleet at all, or at least that the initial engagement was not intended to be offensive in nature. It is striking that the expedition occurred over ten years after the Latin Christian loss of Aqaba, yet why attack in 1182–1183? If the expedition was part of a larger strategy, may it have been a reconnaissance mission, whether as its primary or secondary objective, after all? Perhaps coincidently, following Ernoul’s brief note of the unknown fate of Renaud’s expedition, the writer immediately comments on how the Nile flowed from the Red Sea before traversing Egypt (de Las Matrie 1871, 70). This understanding of a connected Red Sea and Nile was also expressed by other contemporaries (e.g., Gautier-Dalché 1995, 125). Since Antiquity, the source of the Nile had been of keen interest to writers, who often fell into one of three camps: those who believed that the Nile and the Red Sea were separate (usually that the Nile flowed originally from West Africa), those who believed that the Nile flowed directly from the Red Sea, and those who believed that the Nile flowed from the Red Sea, but underground, before resurfacing in ‘Ethiopia.’ This interest in the source of the Nile had by no means waned by the twelfth century. This is evidenced, for example, in Renaud’s former principality at Antioch, where Stephen of Pisa and Antioch wrote his Liber Mamonis (written circa the 1120s) to refute Macrobius‘ (flourished circa 399–422 CE) argument that the Nile flowed from the habitable southern hemisphere by arguing that the flooding of the Nile in the summer during the otherwise dry months occured because of the inverse climatic conditions of the southern hemisphere, thus dismissing Macrobius’ theory of an equatorial ocean (Grupe 2019, 66–68, 112–15).

Given the various potential routes for knowledge dissemination in the region, it is perhaps noteworthy that a variety of non-Latin Christian sources may have added to the Latin Christian understanding of the region in this case, especially regarding the neighbouring kingdoms of Nubia and Ethiopia. For example, on the eve of the Crusades, the anonymous Syriac Ellath Kul-ʿEllān noted that the Red Sea extended towards the kingdoms of Ethiopia and Nubia (Kayser 1889, 258), whilst contemporary non-Latin writers placed the distance between Nubia and Egypt from anywhere between five days for between Aswan and Lower Nubia and forty days for between Aswan and Dongola (e.g., Wüstenfeld 1866–1873, IV:820). Similar times were also noted by contemporary Latin Christians, such as Burchard of Strasbourg, who placed the generic distance between Egypt and Nubia as twenty days, without specifying any details of journey termini, such as Aswan or Dongola, likely from such non-Latin informants (De Sandoli and Sabino 1979–1984, II:402–404). A hybrid understanding of these geographical traditions, along with the increasing contemporary awareness of Nubia and its conflicts with Egypt, notably the two-year raid into Nubia by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn’s brother Tūrānšāh in 1172/1173, may have provided further motivation for venturing into the Red Sea in order to establish possible future routes of access to Nubia. In this case, Nubia’s connections with ʿAidhāb may have been significant. It is also notable that Ibn Jubayr, who travelled through ʿAidhāb not long after the expedition had been captured, described ʿAidhāb as having its own sultan and its population as apparently Muslim Beja (al-Bujah) (1964, 65). However, some contemporary Muslim writers claimed that the Beja were actually Nubians, whilst others distinguished the two, as well as the Ethiopians, to suggest that they were three independent kingdoms, with others noting that they were in fact Christian. One such Muslim writer who described the Beja as Nubians was Abū Az-Zamaḫšarī (died 1144) (1856, 22), whilst Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī (died 1228–1229) distinguished between the Nubians and the Beja, the latter of which were also Christian (explicitly in relation to those at Sawākin) and resided on the Red Sea African coast east of the Nubians (Wüstenfeld 1866–1873, III:182, IV:820). ʿAidhāb was not necessarily under direct Egyptian control.

Ibn Jubayr’s sultan may have been a Nubian eparch, despite his claim that the sultan occasionally met the Egyptian governor to pledge obedience to him, but it is not known from surviving Nubian sources whether Nubia held either direct or indirect control over the port at this time. Moreover, in relation to the gold crisis, which would also have been common knowledge to traders, contemporaries said that the ʿAllaqī gold mines were in the country of the Beja (Wüstenfeld 1866–1873, III:182, III:710). Those who ruled ʿAidhāb were the same as those who controlled access to the region’s gold supply. Not long before the Crusades started, Al-Bakrī (died 1094) commented on the conditions of the mines further inland between Qūṣ and Aswan, stating that the mines had been abandoned due to the dangers posed by various local groups, including Nubians and the Beja (1992, II:618). Even if the Latin Christians were misinformed about who actually held power over ʿAidhāb and the mines of the Eastern Desert, it would still be significant had they been guided by false pretentions of Nubian oversight over the port and the inland mines.

Nubians and the Latin Europeans had already witnessed limited attempted cooperation in the early 1170s, which would make the later Red Sea expedition less noteworthy after all. Multiple Muslim writers relate an attempt by the Commisioner of the Caliphate to communicate with King Amalric to plot to overthrow Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn during a revolt led by Nubian slave soldiers in Cairo, though disagreeing over dates between 1168 and 1173. One testimony is especially notable here, that of Ibn al-Athīr (died 1233). Ibn al-Athīr describes two similar events, one in 1169, which conforms to the general narrative of the uprising described by fellow writers by the Commissioner, and another, similar one in 1174 by another group (1965–1967, XI:345–47, 398–401). It is the second event which should be specifically highlighted here as Ibn al-Athīr explicitly linked this uprising with the Sicilian fleet which attacked Alexandria in 1174 as a result of Sūdān rebels attempting to coordinate with King Amalric a second time (Ibn al-Athīr 1965–1967, XI:412–14). The Sicilian attack was brief and failed, but it showcased the ability to conduct joint attacks between Latin European and Nubian forces, albeit those within Egypt rather than those acting on behalf of the Christian kingdom in these instances. The Nubians and the Latin Europeans were certainly not ignorant of each others’ respective positions. All of this additional context would have contributed to, and possibly influenced, Latin Christian knowledge of the Christian Nubian king’s conflict with his neighbouring pagans, as described by Richard of Poitiers in relation to the year 1172 (1882, 84). Too little is known about the Red Sea expedition to take this much further, but it would appear clear that Renaud’s fleet were not wandering rogues, or even necessarily intent on sacking Mecca, as Muslim writers feared. What, then, were they doing, and could it have had something to do with burgeoning knowledge of Nubia? Currently, evidence is inconclusive. Nevertheless, the expedition was due to a corpus of knowledge that had been gathered throughout the century.

There remains the possibility that Ethiopian actions played some part in informing the Latin Europeans about regional tensions, too. For example, whilst little more can be gleaned from the text, a land grant by the twelfth-century ḥaḍe Ṭanṭawǝdǝm to the church at Ura Mäsqäl in Tǝgray invokes his victory over nearby Muslims, presumably those who resided towards the Red Sea (Derat 2018, 263). Similarly, the conflict that the king of Abitis was engaged in, noted by Roger of Howden (Gautier-Dalché 2005, 216–17), may have contributed to the Latin European understanding of Red Sea tensions. Both of these sources, significantly, indicate conflict involving Ethiopia on both sides of the Red Sea, suggesting an engaged Ethiopia in wider Red Sea affairs. Yet the reign of Lalibäla appears to have been relatively peaceful in its relations with Egypt by the turn of the thirteenth century, with Lalibäla sending an embassy containing exotic animals to the sultan in 1209, according to the History of the Patriarchs; though, as highlighted by Marie-Laure Derat, Lalibäla’s portrayal in the Egyptian Christian text suggests a strong and respected foreign ruler, indicating an influential regional Ethiopian presence despite the otherwise limited evidence (History of the Patriarchs 1943–1974, III.II:189–90; Derat 2018, 160–63). However, this would likely have been misconstrued to support the Latin European attempted engagement towards Nubia, as no comparable illusion of attempted twelfth-century engagement further south, towards Ethiopia, equally occurs in the sources. Nevertheless, a misunderstanding of this activity could readily have built upon more refined knowledge of Nubia further north.

Before concluding, it is important to emphasise that the surviving Latin Christian knowledge corpus of the Red Sea and neighouring powers should not be seen as limited to the texts that have survived. For example, it is most likely that the greater recognition of Nubia over Ethiopia in this earlier period largely reflected the political desires of the Latin Europeans rather than a complete ignorance of Ethiopia in comparison. It is precisely this non-textual knowledge which prospered within the wider Red Sea region, both during Latin European inhabitation at Ile de Graye as well as before and after. The surviving Latin Christian textual corpus should be viewed as a fragment of what was known, and its focus on Mediterranean interactions, whilst being the primary arena of engagement for Latin Europeans, should be considered an example of the conditions of source survival rather than representing the definitive picture as the only region of interest by Latin Europeans during the twelfth century.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted how the development of Latin European knowledge regarding the wider Red Sea region during the twelfth century did not appear within an independent knowledge and exchange vacuum. Whilst largely remaining undocumented, twelfth-century Red Sea entanglements can be seen to inform a growing corpus of Latin European knowledge, particularly regarding Christian Nubians and Ethiopians. Specifically, Nubians and Ethiopians transformed from being obscure peoples during the early Crusades to being key components of Latin crusading discourse in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries due to these often undocumented entanglements in the Red Sea and wider Holy Land, which begin to prosper during the twelfth century. Early indications of this developing discourse can be witnessed in the wider contextualization of the so-called ‘raid’ of Renaud de Châtillon in 1182–1183. The Red Sea should not be so absent from Crusading history, and this article hopes that by providing an example of situating the Crusader States within their wider setting, medieval entanglements and encounters throughout the wider Red Sea region can be analysed, despite a dearth of centralised textual and archaeological evidence. Latin European knowledge of Nubia and Ethiopia developed as a result of such interactions that had remained largely undocumented by all those involved, which has resulted in the hitherto limited discussion in modern scholarship of the Crusades, Nubia, and Ethiopia prior to the more well-known interactions of the later centuries.