The Desert’s Role in the Formation of Early Israel and the Origin of Yhwh

The origin of ancient Israel has been questioned and intensively discussed for almost two centuries by many researchers, from two main schools of thought. One believes the early Israelites came from outside the Land of Cana‘an and conquered it, while the other believes they rose from within Cana‘an, forming a new polity and culture. Scholars are likewise divided whether the Israelite God, Yhwh, originated from the Near Eastern cultural environment or from the desert. A multitude of studies has been dedicated to these two themes, usually separately. This article attempts to examine the connection between the two through several themes: desert roots in the culture of ancient Israel, the origin of Yhwh, Asiatics in Sinai and the Negev, desert tribes and the copper industry, the location of biblical Paran, Nabataean data from Sinai which illuminate biblical issues, and others. By including materials which were previously underutilized or overlooked, these themes may be integrated to form a reasonable scenario of a chapter in the history of early Israel.

Se‘ir, Negev, Sinai, Paran, Shasu, Israel, Yhwh, copper

Israel’s Origin

There is a broad agreement that in many aspects, the ancient nation of Israel1 was quite unusual, as well as its God. However, a long and ongoing debate still questions the origins of both. At least eleven theories have been suggested by scholars as to the origin of Israel; generally and superficially, they are divided into two main ‘traditional’ groups. One sees Israel as created by newcomers, who either conquered Cana‘an militarily, as described in the book of Joshua,2 or took it over through a peaceful settlement process, as reflected from the book of Judges.3 The other group views Israel as originating within Cana‘an, from local ethnic elements, Cana‘anites, and others.4 According to some scholars, the biblical narrative of the creation of Israel (the Patriarchs, the Exodus, and the conquest) was just a legend, written in the seventh century BCE or later, and has no historical background.5

A third option has emerged and gained broad agreement. It states that Israel was created during a long ethnogenesis process from a variety of groups that gathered from different regions: Cana‘anites, ‘Apirw/Ḥabirw,6 Ḥitites, Ḥurites, Amorites, desert tribes, the Exodus people, “Sea People,”7 and others. These heterogenic groups utilized a historical opportunity following the decline of the Near Eastern empires, especially the demise of the Egyptian domination over Cana‘an during the twelfth century BCE. This view was first presented by Petrie (1906, 196–201), continued by a number of later scholars,8 and further developed by Killebrew (2005, 2006, 2017) as the “mixed multitude theory,” a term adopted from the biblical narrative (ערב רב Exodus 12:38) for those who joined Israel on departure from Egypt.9 Some of the tribes were actually present in Cana‘an before the widely believed time of the Exodus (second half of the thirteenth century BCE).10 A close and balanced view has been presented by K.L. Sparks (2007), finding cultural and religious roots in Israel as originating both in Cana‘an and in the desert. A number of scholars see the desert groups as an essential element in this “mixed multitude.”11

The “mixed multitude” option seems most realistic, but there is still room for debate on the identity of the ‘core group’ and on the role of each ethnic element in the formation process of early Israel.

Brief Notes on the Exodus

Naturally, the origin of Israel cannot be discussed without addressing the Exodus. A multitude of studies attempted to reveal the reality behind the story;12 but here it can be related in short notes only. On one hand, it is well known that the Exodus narrative contains many inconsistencies, such as different versions for almost every major detail of the story. Therefore, some scholars reject its historical value (see, e.g., Note 5). On the other hand, the narrative contains many realistic details concerning both the Egyptian and the desert parts of the story,13 so it cannot be totally ignored. Elements in the narrative were probably preserved as oral traditions of different groups at different times. When these were later fused into a national epos, the different versions were not eliminated (see e.g., Petrie 1906, 196–201).

Considering the accumulating information on the archaeology and history of Israel, the Exodus from Egypt can now be seen as one element in a complex and long process of the nation’s creation (see Dever 2003; Finkelstein and Mazar 2007, 51–55), which accords with the “mixed multitude theory” (and see further below).

The Desert’s Role in the Formation of Early Israel

If the view of early Israel as a “mixed multitude” is accepted, the interest of this article, as stated above, is in the desert component of the conglomerate. Many aspects in Israel’s culture and ethnic identity reflect desert roots. Each one deserves a thorough analysis; a few points are presented here:

-

The word “desert” (מדבר) appears in the Bible 268 times; other terms appear as well: ‘arabah (52), ziah (18), and yeshimon (13). The numbers alone may have no significance; however, they become meaningful when compared to the seldom mentions of the desert in the multitude of ancient Near Eastern records.

-

The tribal social structure of Israel is mainly typical to desert societies. Frequent terms like בני יהודה, בני ישראל, בנ קיני,בני אפרים (“sons of Judah,” “sons of Israel,” “sons of Qeni,” “sons of Ephraim,” etc.) are tribal terms, much like the names of Bedouin tribes—Banu Jaraḥ, Banu Suheila, etc. The desert tribal origin of groups in Israel may explain the egalitarian ethos, ideology of simplicity, and the “primitive democracy” of the Judges Period, as it is studied from both biblical sources and the material culture of Iron Age Israel. These characteristics perpetuated in Iron Age II, even though the society became more stratified.14 The ideology of simplicity is best demonstrated by the desert clan Rechabites (Jeremiah 35:6-9) (De Vaux [1971] 1978, 14–15), who saw the simple lifestyle as a source of longevity, i.e., quality of life. The same ideology is expressed later, in the first literary description of the Nabataeans in their early days, by Hieronymus of Cardia (late fourth century BCE, quoted in Diodorus 2. 48. 1-4). For them, simplicity was a way to protect their freedom. The tribal framework of Israel, referring to the northern league of ten tribes, is well reflected in the “song of Deborah” (Judges 5). It is considered among the oldest sources in the Bible (e.g., Stager 1989), probably close in time to the first occurrence of the ethnic entity “Israel” in Cana‘an, first on the often overlooked “Berlin Stelae” No. 21687 of Ramses II, approx. 1250 BCE,15 and then in the renowned Merenptaḥ Stela, 1208-9 BCE.16

-

Numerous small details of everyday life, customs, and rules written in the Bible have direct parallels in the Bedouin culture (Nyström 1946; Bailey 2018). Only writers with a deep desert background could have described these, even if they only absorbed them from their familial narratives. These ‘mundane’ details were rooted deep enough in the Israelite culture to survive the later editions of the Bible.

-

The “tent” (אהל) and related terms are often mentioned in the Bible (325 times). The term was still applied to a “house” long after the Israelites abandoned tents (besides the Rechabites).17 Many terms stemming from “tent” continued to be regularly used throughout the First Temple period (Homan 2002). Again, only writers with a lively memory of living in tents could have written such details that even survived the later editions of the Bible. The importance of the tent is demonstrated in the highly detailed description of the Tabernacle’s construction (12 chapters; Exodus 25-31, 35-40), compared to the short descriptions of construction of the Temple in Jerusalem—one chapter in 1Kings (No. 6) and two parallel chapters in 2Chronicles (2 and 3). The importance of the tent is also highlighted by the refusal of Yhwh to move from his tent to a “house” (i.e., temple, Samuel 17:1-7; 1Chronicles 17:1-5). The legendary nature of the story is obvious, but it still reflects some reality. In the early 1970s, Rahat, the first sedentary Bedouin city, was built in Israel, north of Be’er Sheba‘. Young people willingly moved into the newly built houses, but the elders refused to do so and pitched their tents next to their children’s houses (figure 1). One can imagine similar reactions in the Iron Age I Israel as a source for the story of Yhwh and his tent.

Several researchers pointed to the nomads’ tent as the source for the “four-room house,” typical of the Israelite architecture, the image of which was taken from the present-day, long, rectangular Bedouin tents.18 This connection may have served as another point in favor of the desert origin of Israelite tribes, but this is not the case. In the Negev, thousands of remains of tents are found in hundreds of tent camps. All are circular, approx. 4 meters in diameter, and are dated approx. from 5000 BCE to 1500 CE (Avner 1979, forthcoming152–4, 2002, 12, 2019, 606; Holzer and Avner 2000). The large, rectangular Bedouin tent (figure 1) was probably first introduced into the Negev and Sinai from the Arabian Peninsula, following the Ottoman conquest of the Near East, in the early sixteenth century CE. However, the “four-room house” may have still been related to the desert (see below).

- According to the biblical writers’ viewpoint, the Israelite tribes had close kinship relations with the desert tribes and clans, as reflected from genealogical lists (e.g., Genesis 36, 1Chronicles 1-9) and numerous other verses. Genealogical ties were not necessarily blood relations, they could have been social-political ties (e.g., De Vaux [1958] 1961, 4–6; Gottwald [1979] 1999, 321–3, 334–7, and see below). Edom, for example, is the “brother” of Israel (e.g., Genesis 25:26, Deuteronomy 2:8). Several Edomite and ‘Amaleqite clans, such as Qenaz, Zeraḥ, and Qoraḥ, were also clans in the tribes of Judah, Shime‘on, and Benjamin (Genesis 36:5, 12, 18; 1Chronicles 1:35-6, 2:43, 4:15, 25). Qoraḥ emphasizes these relations. He was the son of Esau—Jacob’s brother and Edom’s father (Genesis 36:14-18); he was a clan of ‘Amaleq-Israel’s enemy (Exodus 17, etc.), but also a clan of Levy, who served in the tabernacle and in the Temple of Jerusalem (Exodus 6:16-24, 1Chronicles 9:19-34), who also held familial ties with Aaron (Exodus 6:20-25), and to whom 10 Psalms are ascribed (44-49, 84-87). Kaleb, Yeraḥmi’el, Qenaz Rechab, and ‘Otni’el were all desert clans affiliated with Qeni and Edom, who joined the tribe of Judah (e.g., Judges 1:16, 4:11-12, 1Chronicles 2:25-50). Midian was the son of Abraham (Genesis 25:2), whose connections with Moses are well known (Exodus 2-4, 18), who also had familial ties with the Qeni, a tribe of the ‘Amaleq federation (Judges 1:16, 4:11).19 In addition, the Israelites are said to have taken 32,000 Midianite women for wives (Numbers 31:9, 18, 35). ‘Amaleq was also the ethnic source of the tribe of Ephraim (Judges 5:14). These few examples,20 with the detailed nature of the genealogical lists, indicate that the complex kinships in Israel were carefully recorded. The very need for detailed genealogy is typical for tribal, egalitarian societies (Gottwald [1979] 1999, 335–7; Faust 2006a, esp. 92-107, and in press; Bailey 2018, 163–72). These lists, therefore, reflect a socio-political reality in which desert clans were actually among the “Proto-Israelites” or joined Israelite tribes. Migration of clans from one tribe to another, and shifts of alliances, are indeed part of tribal reality. A tribe is a rigid social framework regarding rules of behavior, but its composition is flexible.21 For example, the tribe of Judah gradually formed from desert clans and others, including the Shim‘onites (De Vaux [1971] 1978, 546–49; Galil 2001).22 The tribal origin of Judah still appears later, in the extensive use of patronyms in the Bible and in epigraphy in the Judaean Kingdom, in 91% of the names (Golub 2020). This is also found in thousands of Nabataean inscriptions (see below) and among present-day Bedouins.

-

Not only were the names of desert clans common in Israel, geographic names also migrated from the desert to the settled lands. “Reqem” was the old name of Petra (Josephus Flavius, Antiquities 4.7.1); it appears as the city name in a Nabataean inscription at Petra (Starcky 1965), as well as a personal name (CIS II, No. 418). Yet, it was also a town in the land of Benjamin (Joshua 18:17). Qain (Qeni) was not only the name of a desert tribe, but also the name of a town in Judah (Joshua 15:57). “‘Ir Naḥash” (“City of Serpent/Copper”) and “Gay’ Ḥarashim” (“Valley of Smiths”) are identified as the two largest copper smelting camps at the Punon/Feinan area (e.g., Glueck 1970, 98; Aharoni 1979, 36; Levy, Najjar, and Ben-Yosef 2014; Liss et al. 2020) but are also the names of clans in Judah (1Chronicles 4:12, 14). ”Mount ‘Amaleq,” in the land of Ephraim (Judges 15:15), is obviously named after the desert tribe from which the tribe of Ephraim actually stemmed (see above). The very name “Har Se‘ir” (see below) appears on the border between the territories of Judah and Benjamin (Joshua 15:10). Quite clearly, these names migrated from the desert to the settled lands along with the people, much like places settled by Europeans in North America that were named “New Amsterdam,” ”New Hampshire,” “New England,” etc.

-

Compared to all written laws in the Near East,23 the biblical law, rendered in Exodus through Deuteronomy, is exceptional. It is highly humanistic, with high morals and a very strict social order (De Vaux [1958] 1961, 143–63; Alt 1966, 81–131; Albright 1968, esp. 157-8).24 Such a law system, though unwritten, is typical for tribal, desert societies, for whom social solidarity is imperative for survival in the desert (e.g., Ibn Khaldun 1377:II:§§ 4, 7, 8, 13; De Vaux [1958] 1961, 4–14; Gottwald [1979] 1999, 293–337). Biblical and Bedouin laws are similar in many aspects, for example, the role of elders in judgments, resolving conflicts by mediation, protection of tribe members, revenge laws, and more.25 An example of the humanistic nature of the biblical law is evident in the laws of slaves and maidservants,26 which all concern their rights. Contrarily, in the Code of Hammurabi, 29 out of 32 slave laws declare the rights of the slave’s owner or seller, and not one law mentions the rights of the slave himself.27 The unique biblical slave laws could stem from the experience of slavery in Egypt (e.g., Leviticus 25:42, 55; Jeremiah 34:13; Averbeck 2016). Indeed, the biblical writers were aware of the uniqueness of their law system (Deuteronomy 4:8). Several scholars argued that at least the “Code of the Covenant” (Exodus 20-24) and the apodictic laws were originally Israelite, established in the desert.28 The desert nature of the Israelite law is also echoed in the story of Jethro advising Moses on law issues and social order (Exodus 18:17-27).

- Cana‘anite characteristics in the Israelite religion are well known (e.g., Cross 1973; Smith 1990; Keel and Uehlinger 1992), but significant Egyptian influences on the Israelite religion are also evident, born within Egypt mainly during Akhenaten’s rule (second half of the fourteenth century BCE) (e.g., Shupak 2011; Römer 2015, 48–50; Averbeck 2016). The source of this influence could well be Asiatic/proto-Israelite individuals and groups who lived in Egypt during the New-Kingdom.29 Egyptian influence on Israel continued during the Israelite monarchy, mainly on the levels of the administrative system and scribe schools (Mettinger 1971; Shupak 1993, and see below).

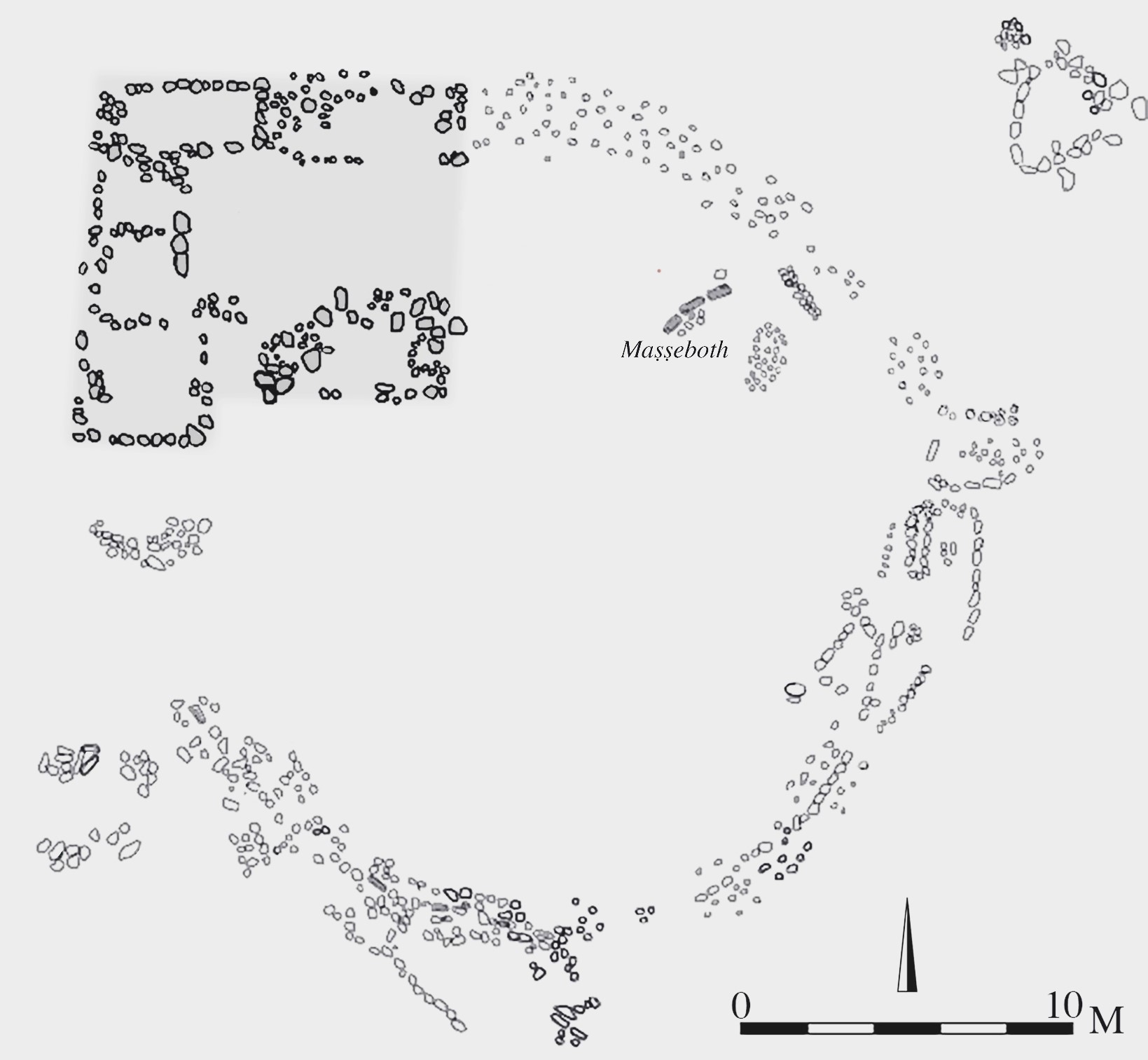

- The desert is highly rich in cult sites, especially maṣṣebot (sing. maṣṣebah—standing stone), dated from the eleventh millennium BCE to the eleventh century CE. Thousands of prehistoric maṣṣebot have been recorded in the Negev and eastern Sinai, in over 450 prehistoric shrines. Maṣṣebot are also found in other cult installations and tombs, as well as in hundreds of sites of later periods. Intensive studies of maṣṣebot in the desert and in the rest of the Near East, including radiocarbon dating, showed that their cult originated in the desert and later spread to the fertile zones (Avner 1984, 1993, 2001, 2002, Ch. 4; Avner et al. 2018; Mettinger 1995, 168–74; Hoffmeier 2005, 246–8). Most of the desert maṣṣebot represented deities (e.g., Avner, above; Mettinger 1995, 140–97; van der Toorn 1997).30 Their function was similar to that of divine statues, but they were actually the opposite; the desert maṣṣebot were natural, unshaped stones, representing the gods as imageless abstracts. Thereby, they actually obeyed a theology that was later eloquently phrased in Exodus 20:22: “(…) and if you build for me a stone altar, do not build it of hewn stones, for if you put your chisel upon it you profane it” (emphasis added). According to this perception, altars and the temple itself should be built of “complete stones,” untouched by iron tools (Deuteronomy 27:5-6; Joshua 8:30-31; 1Kings 6:7). This principle directly relates to the second commandment (Exodus 20:3), prohibiting the worship of any image. Based on archeological evidence, the non-figurative theology was first born in the prehistoric desert religion and later shared by the Israelite religion, by the Nabataeans (Patrich 1990; Avner 2000) and by Islam (e.g., Sell 1914). What was common to these four religions? Their desert cultural foundation.

Maṣṣebot in the Bible present a problem, since eighteen passages prohibit their worship. However, a closer look into the biblical sources reveals the following: Twelve of these passages deal with the destruction of maṣṣebot of foreign gods,31 and three passages denounce maṣṣebot with no clear deity affiliation (1Kings 14:22; 2Chronicles 14:2, 31:1). One verse prohibits any cult of maṣṣebot (Leviticus 21:1) and, surprisingly, only one passage specifically prohibits the cult of maṣṣebot for Yhwh (Deuteronomy 16:21), saying: “(…) Do not set up maṣṣebah that Yhwh your God hates” (emphasis added). More so, in all books of the prophets, only two passages condemn the cult of maṣṣebot in Israel, Jeremiah 2:27 and Micah 5:12, but conversely, in two other passages, in Isiah and Hosea, maṣṣebot for Yhwh are mentioned in a positive light. Isaiah (19:19) says: “In that day there will be an altar for Yhwh in the Land of Egypt, and a maṣṣebah for Yhwh within its border” (emphasis added),32 and Hosea (3:4-5): “For many days the Israelites will live with no king or a minister, with no sacrifice, no maṣṣebah and no ephod or trafim. Then the Israelites will return and seek Yhwh their God (…).” Here, the absence of maṣṣebot and other cult symbols is seen as a time of crisis.33 In addition to all these, at least eleven other passages mention maṣṣebot with no condemnation at all, and they are all associated with the cult of Yhwh.34 An interesting case is the role of maṣṣebot in rituals of establishment or renewal of covenants, between individuals (by Jacob and Laban, Genesis 31:45-51), but mainly between Yhwh and the people: by Moses at Mount Sinai (Exodus 24:4), by Joshua at Shechem (Joshua 24:26-7; DeGear 2015), by King Joash in Jerusalem, (2Kings 11:14-20), and by King Josiah also in Jerusalem (2Kings 23:3; 2Chronicles 34:31). The last two kings, according to the Hebrew text, carried out their ceremony “by the pillar” (על העמוד). In light of the aforementioned verses, the “pillar” is obviously one of the ‘neutral’ words used by the Deuteronomistic editors of the Bible, instead of maṣṣebah (others are יד, אבן, אבנים). Making covenants next to maṣṣebot is also known from Near Eastern texts, most famous is the Sefire Inscription II (Side C, lines 3, 7, 9-10, Fitzmyer 1967, KAI 223), addressing the maṣṣebot on which the treaty texts are written as “House of God” (Aramaic—בית אלהיא). Kings Joash and Josiah, who both conducted aggressive religious reforms, performed their covenant renewal ceremonies next to maṣṣebot which they did not destroy. Since Yhwh was a party in these covenants, he was most probably represented by the abstract maṣṣebah.

To conclude this point, contrary to the impression that the Bible prohibited maṣṣebot, they were legitimate in the cult of Yhwh during the Iron Age, as they are also found in archaeological excavations in Israelite and Judean sites.35 How can that be? Both maṣṣebot and Yhwh originated in the desert (for Yhwh, see below). The aniconic maṣṣebah was the natural representation of the invisible Yhwh. Therefore, the maṣṣebot actually reflect an additional cultural element which originated in the desert and continued to be common in Iron Age Israel. The ‘hatred’ of maṣṣebot by Yhwh can be understood as a later development, exilic or post-exilic, reflecting the ideology of the Deuteronomistic editor.36

The brief review of the above nine points shows that the desert was indeed profoundly imbedded in the culture, reality, and spirituality of ancient Israel (see de Miroschedji 1933).37

The Origin of Yhwh

In the land of Israel, Yhwh shared characteristics with other Near Eastern gods, but originally, he was different. While all other gods act for and through the kings or the state, “Yhwh acts for and through a whole people (…)” (Gottwald [1979] 1999, 696–7).38

Some scholars located the origin of Yhwh in the central or northern Cana‘an/Israel,39 but most support his southern, desert origin, based on three groups of sources:

- Biblical passages repeatedly associate Yhwh with Se‘ir, Sinai, Edom, Paran, Ḥoreb, Teman (Hebrew for “South”), and Qadesh40 (Numbers 10:13,33; Deuteronomy 33:2; Judges 5:4-5; 1Kings 19:8; Ḥabakuk 3:3, Psalms 68:8, 18). All names are in the desert, generally south of Judah.41 In addition, Yhwh is related by the biblical writers to the Qenites/Midianites, the desert tribes (see above). Jethro, the Midianite priest and father-in-law of Moses, led the Israelites’ ceremony and sacrificed to Yhwh at the foot of Mount Sinai (Exodus 18:12). In Judges 1:16, he is also mentioned as the father of the Qenites. The Qenites’ adherence to Yhwh is also reflected from the position of Rechabites, a Qenite clan. Yehonadab, son of Rechab, was behind the Yhwistic reform of King Yehw (2Kings 10), and in Jeremiah 35 the Rechabites expressed their desert ideal in connection to Yhwh.

- Egyptian toponym lists from Soleb, ‘Amara West, and Madinat Habu, of Amenhotep III, Ramses II, and Ramses III, respectively, mention names of the Shasu territories (included in longer topographic lists). ‘Amara West’s list is the most complete, and mentions the names Se‘ir, R’b’n’ (Laban or Reuben), Psps, Šmt, Yhw, and Trbr (Nos. 92-97). Each toponym is preceded by “the Shasu Land (…).”42 Another name appears separately—“snhs Pwn” or “t3 Shasu Punon” (No. 45).43 “The Shasu Land Yhw” occurs in the lists of Soleb and ‘Amara West, while that of Madinat Habu mentions “The Shasu Land Yh”. There is a consensus regarding Yhw/Yh as a tribal territory where Yhwh was worshiped.44 The toponym Yhw also occurs in another topographic list of Ramses III from Madinat Habu,45 but is often overlooked. This list renders a sequence of names indicating a road going from Ḥebron to Athar, Reḥob and Yhw (figure 2). In context with the former three names, this Yhw should be located in northern Sinai.46

- The Hebrew inscriptions of Kuntilat ‘Ajrud, northeastern Sinai, approx. 800 BCE, mention the name of Yhwh six times, including “Yhwh (of) Teman” (“south”) three times, and “Yhwh (of) Shomron” (the capital of the northern Kingdom) once.47

Since these three groups of sources have been thoroughly analyzed by many (see Notes 43-46), only three points are highlighted below:

-

The combination and inter-coherence of all these sources strongly attest to the southern origin of Yhwh, as agreed by most scholars.

-

In the Egyptian inscriptions from ‘Amara West and Madinat Habu, the desert sections of the lists open with “the Shasu land Se‘ir” (in the Soleb list, the first toponyms were not preserved). Therefore, Se‘ir seems to be a general title for the following toponyms.48 This implies that Se‘ir was a large area, encompassing several tribal territories. In the Bible, Se‘ir appears as a synonym of Edom, but sometimes it indicates a distinctive region (see a detailed analysis of the sources in Bartlett 1969). Edom is usually identified as the mountainous area east of the ‘Arabah, while Se‘ir is identified by some as the desert to the west, i.e., the Negev and at least parts of Sinai.49 However, this allocation is not definite. In the view of biblical writers, the Negev was an Edomite territory (Joshua 15:1, 21), as far west as Qadesh Barne‘a (Numbers 20:16, see Grdseloff 1947, 73–74), and as far south as Elot (Eilat) and Ezion Geber on the Red Sea (1Kings 9:26).50 Several scholars see the Land of Se‘ir as a region encompassing both sides of the ‘Arabah.51 The location of some of the toponyms from the three groups of sources may also illuminate the extent of Se‘ir. Teman is usually identified with Edom, the mountains east of the ‘Arabah Valley,52 and Punon is identified with Faynan in the northeastern ‘Arabah, in Jordan, at the foot of the Edomite Mountains.53 Paran should be identified in southern Sinai, approx. 300 km southwest of Punon as the crow flies (see below).

We may conclude from this brief survey that Se‘ir was indeed a large area that included the Edomite Mountains, the Negev, and Sinai as one geographical unit, divided into a number of tribal Shasu territories. This view accords with the plural Akkadian term “the lands of Se‘ir” (“KUR.ḤAL.A Se‘iri / matati Se‘iri,” El-‘Amarna Letter 288:26, Rainey 2015, 116–17).54

- Several scholars have suggested different locations for the “Shasu land Yhw,” where the God was probably worshiped: in the Edomite Mountains (Redford 1992, 273; Blenkinsopp 2008), in northern or northwestern Sinai (B. Mazar 1981; Aḥituv 1984, 121–2),55 the southern Negev and eastern Sinai (Mettinger 1988, 24–28, 1990, 408), and the ‘Arabah Valley (Hoffmeier 2005, 242; Leuenberger 2017, 171–2). Since Yhwh is associated in the three sources with Midian, Se‘ir, Edom, Teman, Punon, Qadesh, and Paran (see above), he was probably worshiped in most of the greater Se‘ir (see Weinfeld 1987, 306; Axelsson 1987, 57–58).56

The southern connection of Yhwh is actually the heart of the “Qenite-Midianite Hypothesis,” seeing Israel and its God emerging from the desert (e.g., Blenkinsopp 2008; Leuenberger 2017; Tebes 2017; Na’aman 2016). The present paper supports the thesis of a southern origin of Yhwh, with additional materials underutilized in published discussions, but sees the origin of Israel as a more complex process.

Possible Occurrences of Yhwh in Other Egyptian Sources

In a copy of a spell from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, dated to the 18th and 19th Dynasties, Schneider (2008) identified the private name “Adoni-Roa‘e-Yah,” Hebrew for “My lord (is) the shepherd of Yah,” or “Adonai Ro‘i Yah” i.e. “My Lord (is) my shepherd”. According to Schneider, the deceased that carried the spell was most probably a foreigner, acculturated into the Egyptian elite. Yah is quite certainly the abbreviation of Yhwh (e.g., Exodus 15:2; Psalms 94:12), the name אדניהו “My Lord Yahw” is well known in the Bible as King David’s son (1Kings 1, 2; 2Chronicles 17:8), and the title יהוה רעי “Yhwh (is) my shepherd” is also known (Psalms 23:1). Other passages also describe Yhwh as a shepherd (e.g., Jeremiah 23:1-6; Isiah 40:1, Ezkiel 34). If Schneider’s reading is accepted, this is the earliest presently known private name bearing the theophoric element “Yah.”57

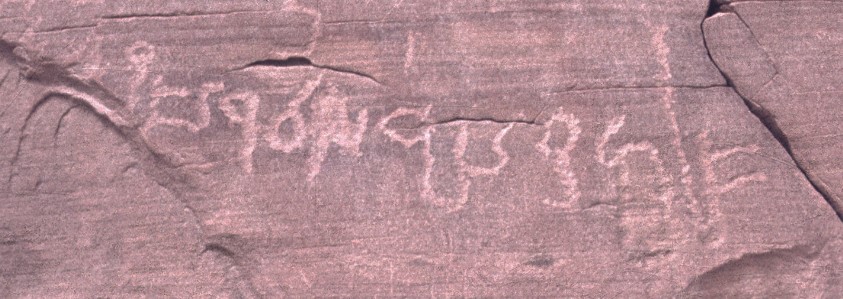

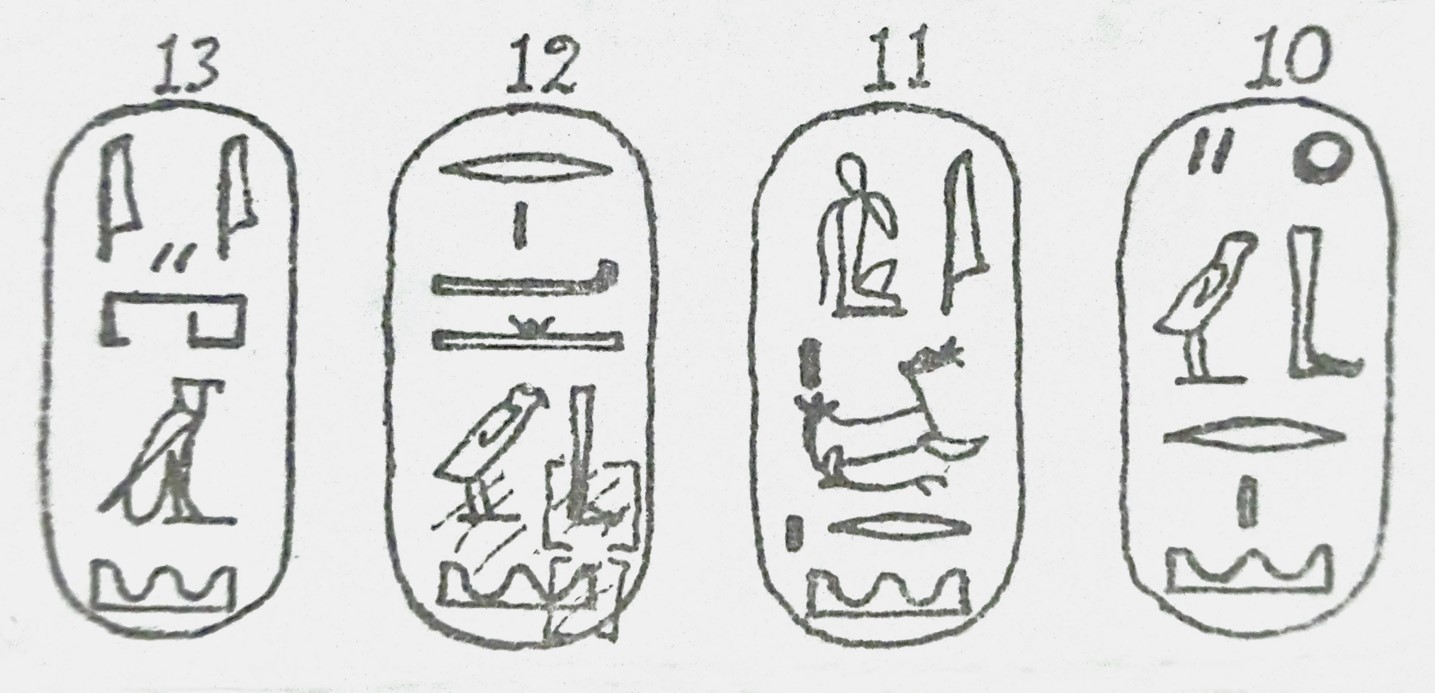

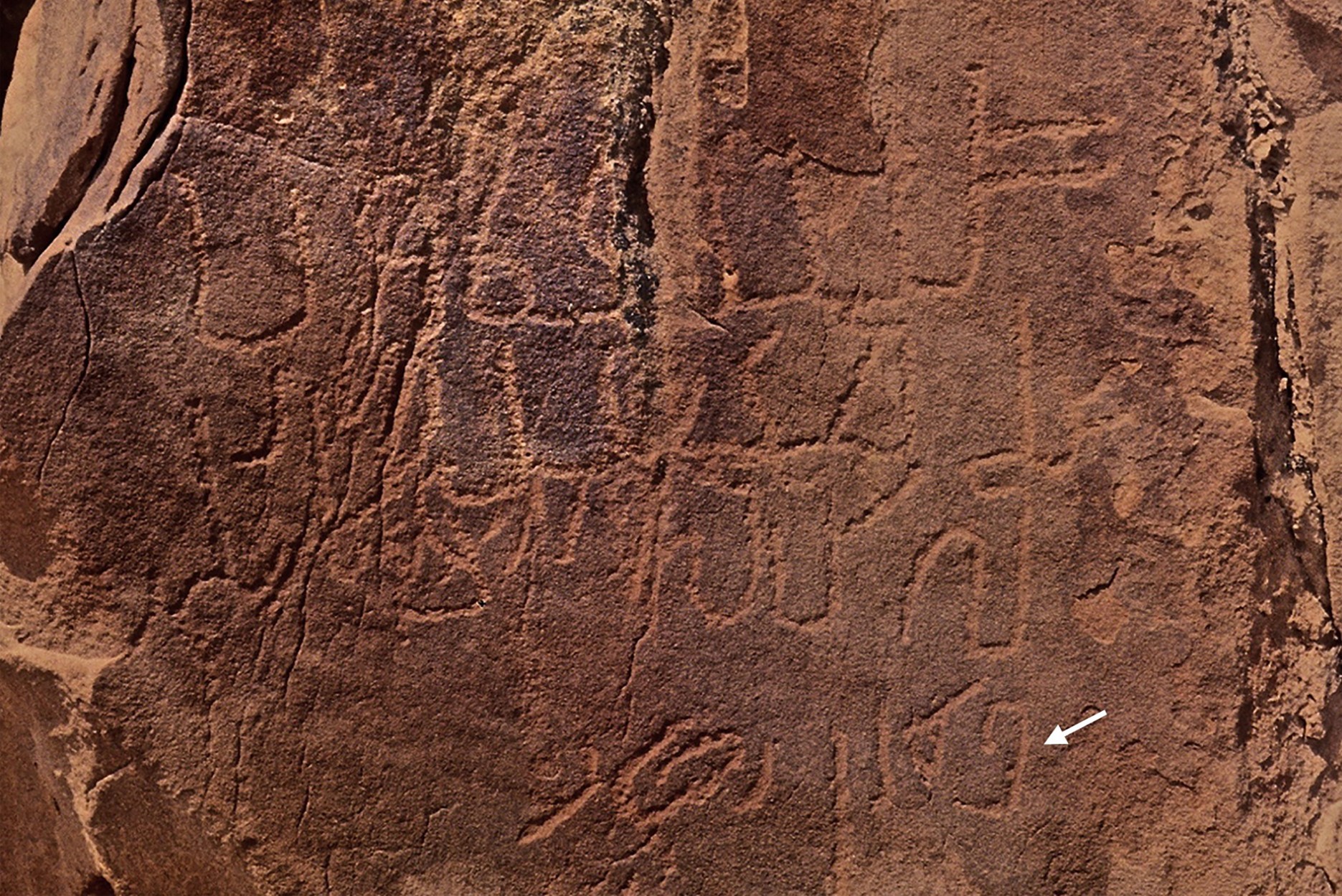

An earlier occurrence of Yhwh may appear on a stela from Thebes, of the 11th Dynasty (late third millennium BCE), published by Gardiner (1917, 35–39). The text, a ‘report’ to an unknown king, includes the following: “(…) I (Akhthoy) brought to him (to the king) the best of the foreign lands in new metal (or copper) of Ba’et, shining metal (or copper) of Ihuiu, hard metal of Menka’u; in turquoise of Ḥrerwotet (…)” Since the name Ihuiu appears with the determinative of “foreign land,” it should denote a territory, much like Yhw in the topographic lists of the New Kingdom. The relation between the metal/copper of Ihuiu and the land of Bi3w / Bia’ brought Gardiner to suggest its location in southwest Sinai, since the name occurs on several stelae from the temple of Serbit al-Khadem, within this region (Gardiner 1917, 36; Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 1–2; Stelae Nos. 53, 90, 117, 141, see Hoffmeier 2012, 109) (see also figures 3 and 11). Gardiner did not make a connection between Ihuiu and Yhw, rather, this was suggested by Weippert (1971, 105–6, Note 41). The name may be pronounced Ihiu / Ahiu (Weippert 1971, 105–6, Note 41) or Ahu (Astour 1979, Note 10).

Identification of Yhwh in the last two sources has been accepted by some scholars58 but rejected by most others due to a different orthography.59 Nevertheless, several points may support Gardiner’s reading and Weippert’s interpretation. One is that orthography of names often changes in transliteration, in our case, a Semitic name written in Egyptian hieroglyphs (see, e.g., Shesha’, below). Second, the region of southwest Sinai was the major source of turquoise for the Egyptians,60 which Akhtoy mentioned several times in his inscription. In addition, the same area is also rich in copper ores, exploited from the early Egyptian dynasties through the New Kingdom, but mainly during the Middle Kingdom (Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 3–7; Tallet, Castel, and Fluzin 2011; Abdel-Motalib et al. 2012). Third, one aspect of Yhwh relates to copper smelting (Jasmin 2018; Amzallag 2019, with references to his previous papers on this topic)61. Hence, the “shining metal/copper of Ihuiu” makes sense. Fourth is the role of “Asiatics” (‘3mw) in both the turquoise mining and the copper industry in the same region (see below).

If the above reading and interpretation are accepted, they may indicate a very early occurrence of the name of Yhwh, and his earliest link with Sinai.

Asiatics in Southwest Sinai and the Proto-Sinaitic Script

Several Egyptian stelae at Serabit al-Khadem, dated to 1800 to 1500 BCE, mention Asiatic persons.62 Some stelae (Nos. 85, 110, 114, 120) mention 10 and 20 unnamed Asiatics, probably simple workers; Stela 110 mentions 20 men from Ḥami, identified with Ḥormah in the Negev.63 Other stelae mention Asiatics by name, in low numbers, indicating they were foremen or professionals. An Asiatic noble, “Khebded, brother of the prince of Retenu,” is mentioned on four stelae (Petrie 1906, 118; Černy 1935, figs. 2–5; Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, Nos. 85, 87, 92, 112). On Stela 112, he is also depicted riding on an ass and escorted by a man and a child. Similar depictions occur on Stelae 103, 115, and 405, without mentioning his name. On the latter, he is shown carrying a ‘duckbill’ axe while the two escorting persons are armed with spears. Remains of yellow, red, black and white paint on the stela indicate his prestigious garment. His role was most probably overseeing the Asiatic workers and negotiating with the Egyptians.64 An impressive stela, of genuine Egyptian style, bears the Asiatic name: ’Shalem-Shama‘, “(the god) Shalem heard” (Giveon 1981).65 Obelisk 163 belongs to three brothers, one is Qeni (Keni),66 so most probably they were Qenite tribesmen. A high official with an Egyptian name, “Amnisoshenen… the Asiatic,” owned seven stelae (Nos. 93-99, Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 100–106). Stela 423 was dedicated by ‘Aper-Ba‘al (Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 212). A number of stelae (e.g., 86, 105, 412) bear the name Ḥor/Ḥori, which, according to Kitchen (1998, 88), is also Semitic, appearing 15 times in the Bible (Exodus 17:10, 12, 24:14 etc.), but possibly of Egyptian origin (Muchiki 1999, 211).

Stela 81 mentions a scribe named Rua/Lua, (Černy 1935, 384; Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 90), equated by Giveon (1978, 134) with the biblical name Levi.67 This stela is of interest to this study for several reasons. First, Lua was not the only known Asiatic scribe mentioned in Egyptian inscriptions. Stela 123b at Serabit al-Khadem belonged to “the judge, chief lector priest, priest and scribe, the Asiatic Werkherephemut” (Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 128; Giveon 1978, 157). Other Asiatic scribes are known from Egypt. An Asiatic scribe named Rafi left a small stela at Qantir/Avaris (Kitchen 1998, 89, with references). Dedia was the Asiatic scribe of Seti I (Alon and Navratilova 2017, Ch. 7). Ḥori (see above) was the name of the Asiatic author of the “Satirical Letter” Anastasi I, with a deep knowledge of Cana‘an. (ANET 475-9; Alon and Navratilova 2017, Ch. 9). He also bore the title mhr (Anastasi I, 18:3-6) Hebrew for “swift” or “intelligent” (see סופר מהיר, Psalms 45:2; Ezra 7:6). Still another scribe’s name, “עזרממ” (‘Oz-Romem), is possibly mentioned in a Proto-Sinaitic inscription from Timna‘ (Wimmer 2018).68

Second, finding Asiatic scribes in Egypt should not be taken for granted. Learning the Egyptian language, reading and writing hieroglyphic texts, with approx. 700 signs and additional complexities, was a difficult task that required talent and long training. Scribe students in Egypt had to begin their learning in childhood, under a harsh discipline and high demands; they had to be knowledgeable in many fields, including mathematics. When they finally became scribes, they gained a high social status and promotion opportunities (Williams 1973). In this light, it is remarkable that Asiatics could become official Egyptian scribes.

Third, the scribe’s name on Stela 81, Lua, probably Levi, is specifically interesting. Levites and priests later mentioned in the Bible bear Egyptian names (Ḥophni, Pinḥas69, Pashḥur and others) and attest to the service of Levites and Asiatic priests in Egypt (see Aḥituv 1970; Hoffmeier 1997, 223–34, 2016, 18–31; Muchiki 1999, 221, 222, 224). An important example of an Asiatic with such a career is “Ben-Azan/Adon” (Hebrew, “Son of a Lord”). He was brought from Cana‘an to Egypt as a child in the time of Merenptaḥ, educated to be a “priest of pure hands,” and was given the Egyptian name Ramsesemper‘. He later rose to a high position in the court of Ramses III and left behind nine stelae. One of his accomplishments was the resumption of Egyptian involvement in the copper production at Timna‘ after a break of some 20 years (Schulman 1976; Avner 2014, 140). The scribe on Stela 81, named Lua/Levi from Serabit al-Khadem, recalls several Levite scribes who are later mentioned in the Bible (1Chronicles 24:6, 2Chronicles 34:13). Qeni on Stela 163 is also interesting, since four Qenite families of scribes also appear in the Bible (1Chronicles 2:55). Another scribe affiliated with the Qenites was Ye‘uel (2Chronicles 26:11), a member of Zeraḥ (1Chronicles 9:6), an Edomite clan (Genesis 36:13, 17) related to Qeni, to Midian, and to Moses (Numbers 10:29; Judges 4:11). An additional family of scribes included Shia’ (שיא) / Shesha’ (שישא) / Shausha’ (שושא), the scribe of King David (2Samuel 20:25, 1Kings 4:3, 1Chronicle 18:16 respectively), and his sons Eliḥoref and Aḥiyah were the scribes of Solomon (1Kings 4:3). The father’s name is Egyptian, stemming from the title sš- “scribe” (Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 18–19 etc.; Mettinger 1971, 25–30; Muchiki 1999, 226; Shupak 1993, 350).

Altogether, we see here an accumulation of data on Asiatic scribes from Middle Bronze Sinai, probably from the Late Bronze Timna‘, and then from the Iron Age Bible. Many of them had desert roots and tight connections to Egypt. The timespan of these data may seem too long to bear any relevance, but as we know from Egypt and from Shia’, Eliḥoref, and Aḥiyah in the Bible, the scribes often perpetuated their profession within their families, from one generation to another (Williams 1973). Such a theoretical continuous scribal tradition may explain the Egyptian influence on the scribe schools in Iron Age Israel (Mettinger 1971, Ch. 10; Shupak 1993, esp. 347-54). Indeed, according to Muchiki (1999, 324), the roots of this influence (many Egyptian names and loanwords in Hebrew) can be traced back to the Middle Kingdom.

The 44 Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions from southwest Sinai (Serabit al-Khadem, Wadi Naṣib, and Wadi Magharah) are important fingerprints left by the Asiatics.70 The idea behind this script was revolutionary, selecting a small number of pictograms to form a simple, acrophonic script. Most letters were adopted from the Egyptian hieroglyphs of the Middle Kingdom, around 1840 BCE,71 but were vocalized differently, fitted to Semitic speech. The question is, who were the Asiatics behind this invention? Egyptian inscriptions at Serabit al-Khadem state that they originated from Retenu, a term usually applied to Cana‘an, but also to the broader Levant (Redford 1992, 200). Helck (1971, 266–7) went further to show that the term Retenu was originally applied to Se‘ir. According to Petrie (1906, 118), the Asiatics at Serabit al-Khadem came from southern Palestine and from Sinai, while Gardiner (1916, 14) and Černy (Černy 1935, 389) emphasized Sinai as their province. Darnell (Darnell et al. 2005, 88, 91) ascribed the invention of the script to Asiatic mercenaries in the Egyptian army, while Giveon (1978, 143) suggested that these Asiatics came to southwest Sinai from Egypt. This could be true of those who bear Egyptian names. Goldwasser (e.g., 2014, 363, 371) sees them as Cana‘anites, but also as “desert experts.” Most scholars saw these Asiatics as intelligent and skilled persons who developed their capabilities through tight contacts with the Egyptian culture and through exposure to hieroglyphic monuments.72

From the data gathered here it seems that the Asiatics in southwest Sinai were mainly the inhabitants of the greater Se‘ir, i.e., the desert people; for them the desert was not hostile and their knowledge of its environment was most valuable. Learned Asiatics, like Lua/Levi, Qeni, and Werkherephemut, could well be among those who invented the first alphabetic writing in the world. Their language was quite close to the biblical Hebrew, with similar personal names and terms (e.g., Albright 1969, 38–45; Sass 1988, 220–22), or may even have been proper biblical Hebrew (Petrovich 2016, esp. 6-13, 186-200).73 These Asiatics may have also been one source for the wealth of Egyptian idioms included in the biblical narrative (Shupak 1993, 2011; Hoffmeier 2016; Hess 2016; Noonan 2016; Averbeck 2016) and the source of Egyptian influence on the Israelite scribe schools during the monarchy period (see above).

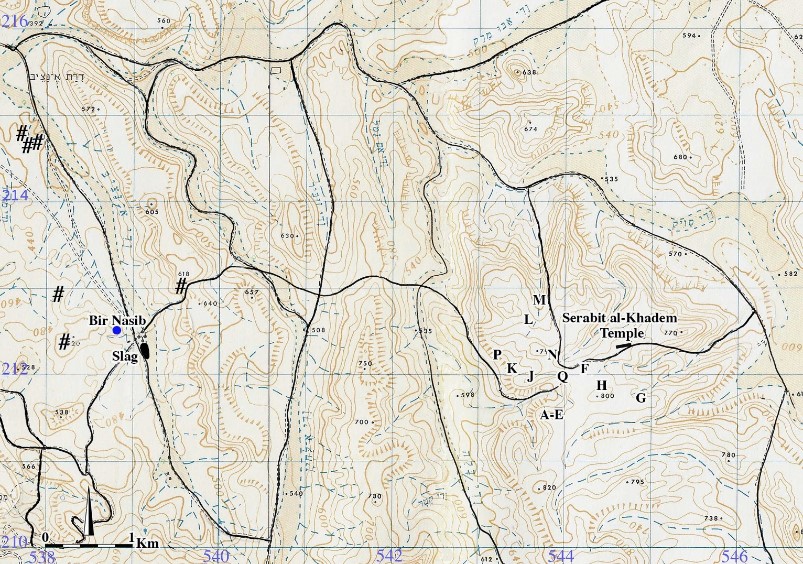

Besides mining turquoise in southwest Sinai, the Asiatics were also strongly affiliated with the intensive copper industry. This includes the large pile of copper slag at Bir Nasib (approx. 150x250 m, figure 3), and smaller smelting sites have been described by Petrie (1906, 18, 51–52) and by Gardiner et al. (1955, 3–7, 30–31); over 3000 furnaces (!), arranged in long batteries, were discovered by Tallet et al. (2011) on the hills above Wadi Naṣib. The copper mines in the region were re-surveyed by Abdel-Motalib et al. (2012, 12–15), who added new sites and data. The furnace batteries are attributed to the Egyptians, mainly of the Middle Kingdom, but no signs of Egyptians were found around the copper mines (see Gardiner, Peet, and Çerny 1955, 7), implying that they were operated by Asiatics. Copper workshops found in Mines G and L at Serabit al-Khadem were also employed by Asiatics (Beit-Arieh 1985, 1987), who left 17 Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions in and around them (Sass 1988, Table 1).

The Shasu and Copper Industry

During the New Kingdom, the Asiatics were termed “Shasu” by the Egyptians and were mentioned in some 50 Egyptian texts. The word means “wanderers,” those who “move on foot,” or “herders.”74 They were described indeed as shepherds living in tents, warriors, enemies of Egypt, captives taken by Amenhotep II and III, Seti I, Ramses II and III, but also as mercenaries incorporated in the Egyptian army. During years of droughts they were sometimes permitted to enter into the eastern Delta with their herds for water and pasture;75 some Shasu were depicted as nobles.76 Geographically, as noted above, they were mainly mentioned within Se‘ir, Edom and northern Sinai, but also within Egypt, and even reaching Syria and Lebanon. The Shasu were not a marginal minority. The list of captives taken by Amenhotep II in his nineth year campaign to Cana‘an (1444 BCE) included 36,000 Ḥaru (Cana‘anites), 3600 ‘Abiru, 15,200 Shasu, and others (ANET 247; Helck 1971, 486–7). Due to their lifestyle, they were often equated with the “Patriarchs” of the book of Genesis and with early Israel.77 Since they were thoroughly discussed by scholars (Notes 43-46, 74, 75), only a few issues are addressed here:

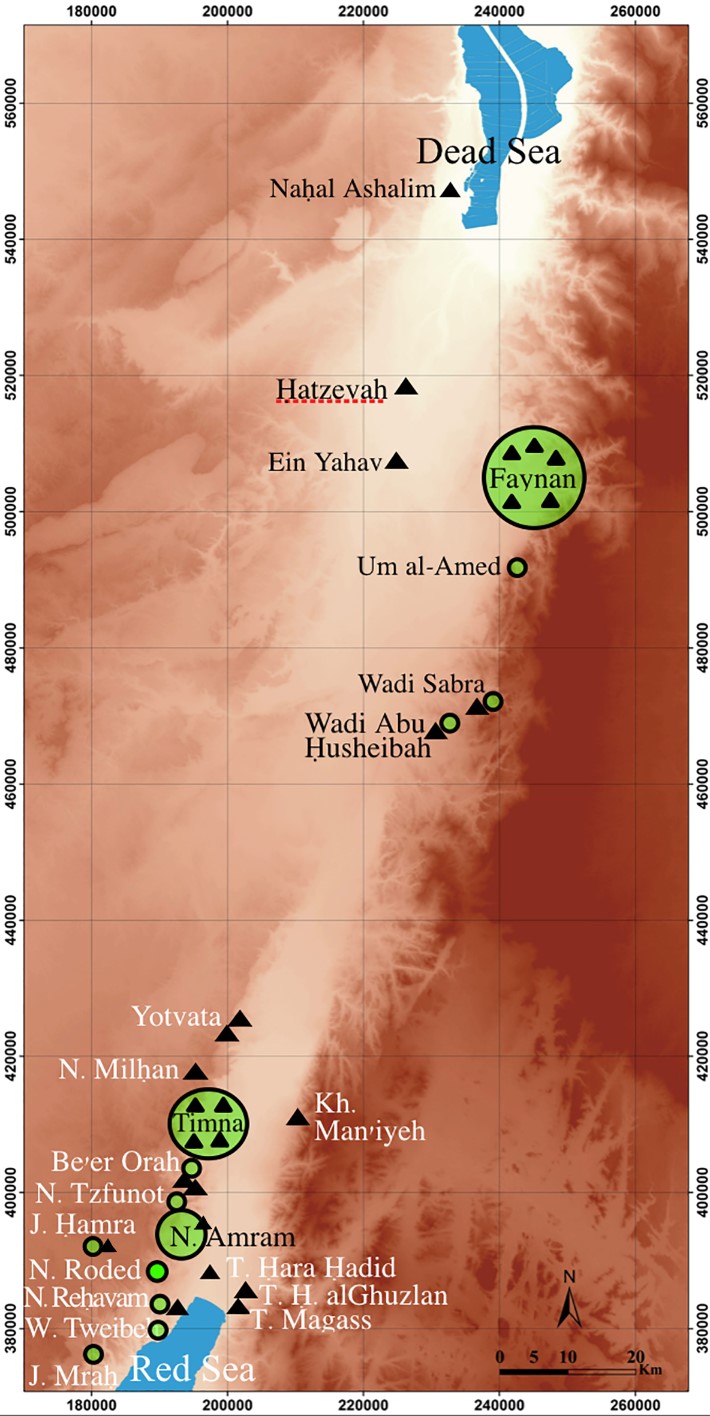

Affiliation of the Shasu with the copper industry creates increasing interest, especially in the ‘Arabah Valley, which is rich with copper deposits (figure 4). Following the studies of Rothenberg at Timna‘ (e.g., 1972, 1988, 1999a, 1999b), the Late Bronze-Iron Age copper mining and production was accepted by many as the outcome of Egyptian initiatives, control, and technology. However, new studies show a different scenario. The southern ‘Arabah was indeed conquered by Ramses II (approx. 1280 BCE), and was occupied (with an interruption of 20 years) until the time of Ramses V (approx. 1150 BCE; Schulman 1988, 145). Many Egyptian artifacts were discovered in the miners’ sanctuary at Timna‘ (Rothenberg 1988), but the actual role of the Egyptians in the industry was limited. The sanctuary, in fact, belonged to the local desert tribes, whom the Egyptians joined. Ḥatḥor was not the owner of the sanctuary but only a guest of the local gods. The technology of mining and smelting, as well as the organization of the work, were all in the hands of the desert people (Avner 2014). None of the other copper mining centers along the ‘Arabah, Naḥal ‘Amram (Avner et al. 2018), and Faynan (Punon) showed any signs of New Kingdom Egyptian control or presence.78 More so, many tens of radiocarbon dates from these three centers and from smaller smelting sites along the ‘Arabah prove that the tenth century BCE was the heyday of the copper industry, 150 to 250 years after the last Egyptian presence at Timna‘.79 Copper production and trade on such an enormous scale required thousands of workers, sophisticated skills, complex logistics, and a high level of organization.80 Seemingly, the only potential power to administrate such an industry at that time was the United Monarchy of Israel (David and Solomon); however, no sign of the kingdom’s presence was found in the copper mining and production centers along the ‘Arabah. Judaean pottery, which is common in contemporary sites in the Negev Highlands (Cohen and Cohen-Amin 2004, esp. 121-141), is absent in all these copper centers. Hence, the only other remaining candidates to control this immense industry were the desert inhabitants, the Shasu.81 In addition, the huge cemetery at Faynan (Fidan 40), where 287 tombs were excavated (out of approx. 7000), is attributed to the Edomite Shasu, based on the site’s context, on the grave goods, mortuary practices, the cemetery‘s egalitarian nature and the absence of nearby contemporary stone-built habitations (Levy, Adams, and Muniz 2004; Levy 2009; Beherec, Najjar, and Levy 2014; Beherec et al. 2016). It is even suggested that the organization of the Shasu around the copper industry brought them to a level of “tribal kingdom” (Ben-Yosef 2019) which was actually the base for the rise of the Edomite Kingdom (e.g., Levy, Adams, and Muniz 2004). Because of the great importance of the ‘Arabah as a copper source, and due to the Shasu domination of the metal industry, one of the suggested identifications of the “Shasu land Yhw” is in this very region (Hoffmeier 2005, 242; Leuenberger 2017, 171–2).

Another point may connect the Shasu with the ‘Arabah copper industry. In excavations of Timna‘ Site 34, six colored tassels were found (figure 5) (Ben-Yosef 2016, Fig. 10; Sukenik et al. 2017). In several presentations of Shasu in Egyptian reliefs and paintings, they were depicted as warriors, armed with bows and arrows and wearing tasseled kilts. Giveon (1971, 241, Pls. II, III) equated these tassels with the biblical ones (ציציות) that the Israelites were instructed to wear (Numbers 15:38-9; Deuteronomy 22:12; Shamir 2014), and that Jewish observants still wear today. Tasseled garments were also worn by others in the Near East, mainly by gods and nobles (Bertman 1961), but Giveon’s suggestion may be valid in light of another discovery from Timna‘. To date, 19 prestigious textile fragments were found in Site 34, dyed red and blue (figure 6); similar fragments were also found in Site 30 and in the miners’ sanctuary (Site 200, Sukenik et al. 2017 with references). These recall the “blue and scarlet” textiles (תכלת וארגמן) mentioned 28 times in the book of Exodus, relating to the tabernacle’s fabric sheets (e.g., 26:1,31,36; 27:16) and to the priests’ garments (e.g., 28:8, 33; 39:1).82 This is likely an additional link between the Shasu, the large-scale copper industry, and possible biblical-Israelite customs. The presence of prestige textile at Timna‘ links with the Egyptian depiction of Shasu nobles wearing fancy garments (Note 76), with the prestige garment of Ḥebded at Serabit al-Khadem (see above), with further finds from Timna‘ indicating the rich diet of the copper smites (Sapir-Hen, Lernau, and Ben-Yosef 2018), and with parallel finds from the Naḥal ‘Amram mines indicating the high quality diet of copper miners in later periods (Avner et al. 2018).

Additional finds from Timna‘ may associate the Shasu with Israel. In smelting Site 30, Conrad and Rothenberg (1980, 205–8, Beilage 27) excavated a building from Phase I, dated by them to the thirteenth century BCE, partially covered by a slag pile date by a series of 14C dates approx. 1050 to 900 BCE (Ben-Yosef et al. 2012, 55–62). The building consists of an elongated courtyard containing a silo and a grinding stone, flanked by two aligned pairs of rooms on each side. The walls separating the courtyard from the rooms are built of alternating monoliths and fieldstones (figure 7). The masonry characteristics and the ground plan recall those of the renown Israelite “four-room house.” The perpendicular backroom, typical for this type of house, seems missing here, but a southwestern corner, slightly exposed by the excavators (but not reported) hints at its existence.83 A larger building resembles “four-room house” (approx. 12x12 m), discovered in ‘Uvda Valley, 20 km northwest of Timna‘ 30, situated among a scatter of tens of tent camps, and belonged to an agro-pastoral population (figure 8) (Avner 1979, 18). Finds from the surface and from a small probe included pottery sherds of the same three types known at Timna‘ (wheel-made, hand-made Negebite, and decorated Midianite). This building most probably served public functions for the population, similarly to a later Nabataean public building in the same area, also built in the middle of a large cluster of tent camps (Avner 2019, 606–8, fig. 29). As discussed above, the best candidate for the population of Timna‘, as well as of ‘Uvda Valley, is the Shasu. “Four-room houses” discovered at Thebes, Egypt, were also attributed to Shasu workers, “closely related to the Proto-Israelites” (Bietak 2015, 18–21).

The central Shasu group in the copper industry seems to be the Qenites, discussed in a number of studies.84 Qain (Cain), their ancestor, is mentioned as the first copper and iron smith (Genesis 4:22; 1Chronicles. 4:13–14). He was cursed by God to be a “wanderer” (נע ונד, Genesis 4:11-12), the exact parallel to the Egyptian term “Shasu.”85 The Qenites’ affiliation to copper production seems to have a long history. The names Qeni already occurred at Serabit al-Khadem in the early second millennium BCE (see above), and later occurred as Qini/Qinu/Ibn-al-Qini in tens of Nabataean inscriptions in the same area of southwest Sinai (see below). Still later, the Jewish tribe of metal smiths, Qainuqa (Kinuka), lived in the Northern Ḥijaz (Midian) until the Time of Moḥammad (Wensinck 1978). All these variations of the name stem from the Hebrew root קנה, which means “create” and “smith.”86 The smith appeared as a magician, turning rocks into metal and ‘creating’ a new substance.87

Pertinent to this scenario is the distribution of the “Negebite” and “Midianite” pottery. The former contains crushed copper slag as a temper (Yahalom-Mack et al. 2015; Martin et al. 2013) and is therefore certainly locally made, in the Negev, in northeastern Sinai and Southern Jordan. The latter was produced in Qurayya in northern Hejaz, ca. 150 km southeast of ‘Aqaba, found in copper production centers along the ‘Araba and in other sites as far north as Gezer. Both types indicate that Qenites, Midianites, and other Shasu groups were involved in the copper industry, while the Midianite pottery also attests to international trade of copper and of ‘Arabian exotic goods (Rothenberg and Glass 1983; Brandle 1984; Jasmin 2006; Tebes 2006, 2017; J. Tebes 2007a, 2007b). Indeed, copper from the ‘Araba was spread during the Iron Age to several destinations in Cana‘an/Israel (Yahalom-Mack et al. 2014; Yahalom-Mack and Segal 2010, 2011) as well as to Egypt (Vaelske and Bode 2019).

Finding the Qeni in the Sinai inscription, the Qenite connection with the copper industry, their alliance with Israel, and joining the tribe of Judah (e.g., Judges 1:16, 4:11, 1Samuel 15:6) brings us a step closer to the “Midianite-Qenite Hypothesis.”88

The Geographical Connection of Kuntilat ‘Ajrud

The Hebrew inscriptions and drawings of Kuntilat ‘Ajrud have been analyzed in many publications89. Here, we only mention the recurrence of the name Yhwh in the inscriptions: three times associated with Teman, once with Shomron (the capital of the northern kingdom) and twice with no geographic association. Other gods are mentioned too: Asherah, four times (with Yhwh), El twice, and Ba‘al once (Aḥituv, Eshel, and Meshel 2012).

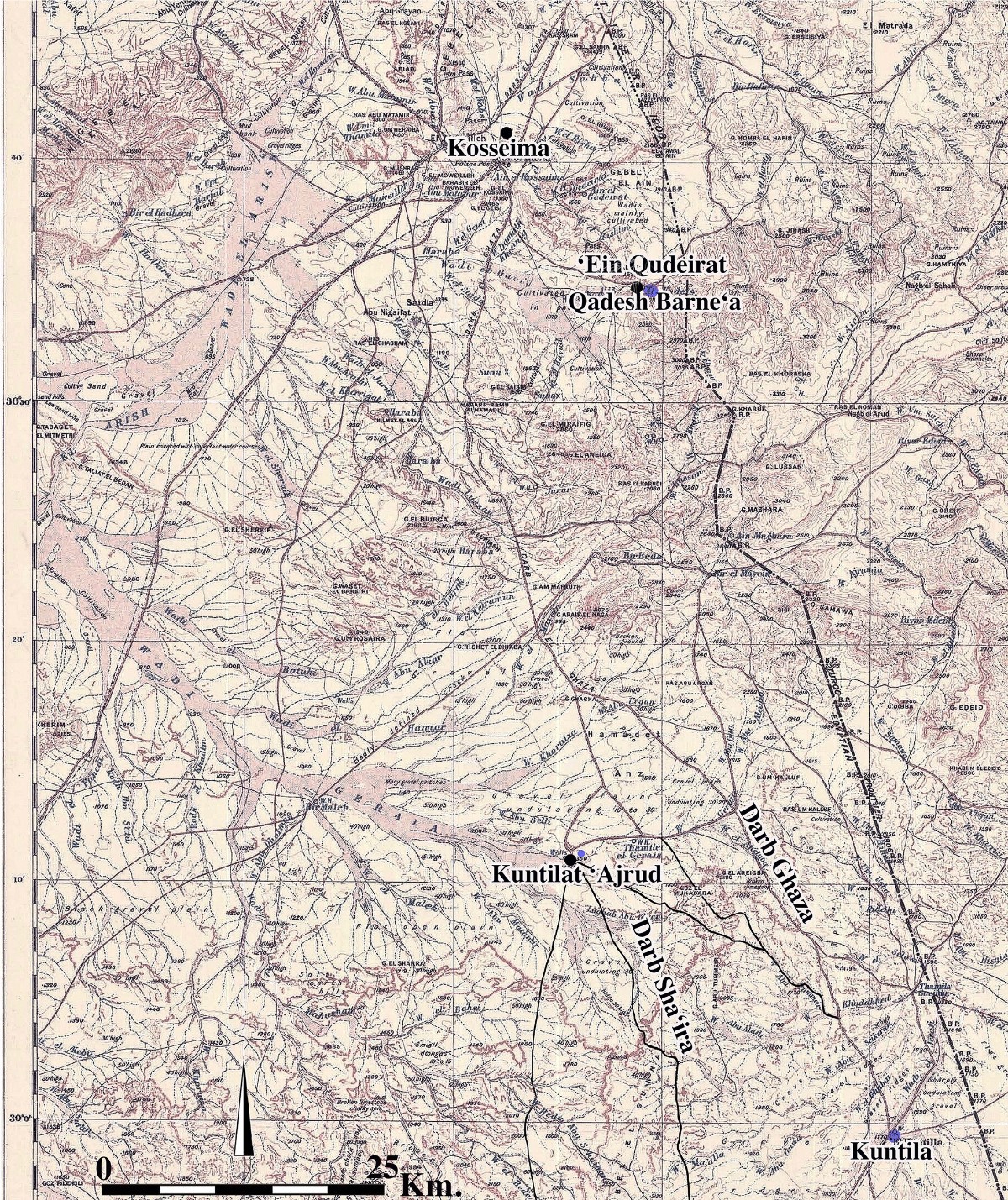

The site’s location requires specific attention. Kuntilat ‘Ajrud is built on the top of an isolated hill in northeast Sinai, 50 km south of Qadesh Barne‘a. According to Meshel (1978, 2–6, 21, 1983, 52), it is located next to a junction of three roads: One is Darb Ghaza,90 an important trade route connecting the Mediterranean ports with the Gulf of Eilat, identified by Meshel (1981) with the biblical דרך ים סוף (“The Red Sea Road”). Second is a road leading to southern Sinai, and third is a road crossing Sinai from east to west. Based on this location, on architectural remains and finds, Meshel suggested two functions of the site: a trade station on the way to the Red Sea, and a religious center. With time, Meshel (e.g., 2012, 3–4, 65–69) concentrated on the religious nature of the site in light of the inscriptions and drawings, but still connected it to Darb Ghaza and to Eilat. Subsequently, several scholars emphasized the function of the sites as a road-station, serving Israel’s international commerce with ‘Arabia and Africa, through Eilat.91

This view, however, requires a correction. The road map of the area is actually more complex, as can be seen on “Newcomb Map” of the Negev (figure 9). Since the map was prepared before the introduction of motor vehicles into the desert (in 1913/14 by the British Intelligence, published in 1921 by the Palestine Exploration Fund), it reliably represents the desert network of ancient-traditional roads.92 According to this map, the junction of Darb Ghaza and the road crossing Sinai from east to west is not near Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, but at Kossaima, northwest of Qadesh Barne‘a. The road on which Kuntillet ‘Ajrud is actually situated branches off Darb Gaza 13 km north of the site, and is 15 km west of the Darb Gaza (figure 9) (see Meshel 2012, 3 and Fig. 1.1). Therefore, Kuntillet ‘Ajrud is not connected at all to Darb Ghaza and does not control it. If indeed the site were associated with Darb Ghaza and with trade, it would have been built on this very road, for example, on the hill just southwest of the important water well of Kuntilah (figures 9, 10, 11), 34 km southeast of Kuntilat ‘Ajrud. Passing through Qadesh Barne‘a to Eilat via the road on which Kuntilat ‘Ajrud is truly situated would add two unnecessary days to a caravan journey. More so, the most efficient route for caravans from Jerusalem or from Shomron to Eilat or Ezion Geber is not through Darb Ghaza but through the ‘Arabah Valley. This route was well defined by Burckhardt (1822, 443), who described an eight-day camel ride from Ḥebron to ‘Aqaba through the ‘Arabah: “(…) for this is both the nearest and the most commodious route, and it was by this valley that the treasures of Ophir were probably transferred to warehouses of Solomon” (in Jerusalem). In addition, along the ‘Arabah there are many more water sources and more pasture for the camels. Compared to Burckhardt’s trip, Robinson and Smith’s camel ride (1856, 173) from ‘Aqaba to Ḥebron, through Darb Ghaza, required ten days.93

The true destination of the road running through Qadesh Barne‘a and Kuntilat ‘Ajrud was southern Sinai and is presently named Darb Sha‘ira, after a mountain’s name further south (figure 11). Based on geography and similarity of the names, Ilan (1970) suggested this road may be identified as the biblical דרך הר שעיר (the “Mount Se‘ir Road”). The name is certainly interesting in its biblical context, following Deuteronomy 1:1-2: “(…) in the ‘Arabah—opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Ḥazeroth and Di-Zahab. It takes eleven days to go from Ḥoreb to Qadesh Barne‘a by the Mount Se‘ir Road.” Scholars commonly agree that Qadesh Barne‘a is located at ‘Ein Qudeirat (e.g., Hoffmeier 2005, 122–4; Cohen and Bernick-Greenberg 2007, 4, both with references), an important oasis with a running stream (figure 12), while the biblical name, Qadesh, has been preserved in another spring named ‘Ein Qadis, 8 km to the southeast. An Iron Age fortress with four main strata has been excavated at ‘Ein Qudeirat (Cohen and Bernick-Greenberg 2007). The lowest (Stratum 4) is a small rounded “fortress” or “enclosed settlement”94 dated by radiocarbon from the late thirteenth to the early ninth centuries BCE.95 This is the period of the Exodus, the Judges, and the United Kingdom. In sum, Darb Sha‘ira runs from Qadesh Baene‘a through Kuntilat ‘Ajrud and the foot of Jebel Sha‘ira southward to southern Sinai. This connection is also illuminated by eight pieces of sycamore and Pistacia wood found in the site which originated in southern Sinai (Liphschitz 2012, 345). The significance of this point is addressed in the next paragraphs.

The “Desert of Paran” and “Mount Paran”

One of the puzzles in reconstructing the geography of Se‘ir is locating the “Desert of Paran” (Genesis 21:21, Numbers 10:12, etc.) and “Mount Paran” (Deuteronomy 33:1-2), a synonym of Mount Sinai/Mount Ḥoreb. Today, “Naḥal Paran” is known as the largest wadi in the Negev, a name used by Anati (e.g., 2001, 47–54) as one argument supporting his identification of Mount Sinai with Har Karkom, west of Naḥal Paran. However, this name was given to the wadi by the “National Committee of Names,” nominated in 1949 by the young Israeli government in order to replace older ‘Arabic names with Hebrew ones. In this case, the Bedouin name “Wadi Jirafi” was converted to “Naḥal Paran,” on no historiographic ground.96

The real Paran must be searched for in the igneous mountain region of southern Sinai. Much of this region is drained by the great Wadi Feiran, which includes the largest oasis in the peninsula, a five-kilometer long palm grove (figure 13), and a Nabataean-Byzantine town named Pharan/Phara/Fara (see below). The ‘Arabic name of the wadi obviously follows the biblical name, much like Punon-Faynan (see above), but the similarity of names is not enough to determine its location. In this area, 43 Nabataean inscriptions were included in the CIS II in 1906, bearing the first or surname “Paran” (פארן, figure 14), spelled just as in the Bible. Two similar inscriptions were added by Negev (1991, 54), from southern Sinai and from Wadi Hajjaj, a four day walk from the Feiran Oasis on the way to Aila/Eilat. The latter has been inscribed by “Paran son of ‘Abdalba‘li” (פארן בר עבדאלבעלי; Negev 1977b, 58–59, No. 233), known as a citizen of Wadi Feiran, (CIS II, No. 1512 and see the map figure 11).97 Besides the latter, all other inscriptions are restricted to the Wadi Feiran-Wadi Mukatteb area. This is the only region naming פארן (Paran) in the entire Nabataean domain, encompassing most of Jordan, northern Hejaz, the Negev, and Sinai (e.g., Patrich 1990, 23). This means that the biblical geographical name has been preserved in this area for centuries, obviously by generations of local population. Support for this point and its implications are discussed below. In the second century CE, Pharan was mentioned by the Roman geographer Ptolemy (V.16; Stevenson 1991, 128) as a kome (village), but in the fourth century CE as a polis (town) by Eusebius (Onomasticon 142, 22-25; Freeman-Grenville 2003, 92). Also in the fourth century CE, Phara was marked on the Tabula puentingeriana (Nebenzahl 1986, 20–25), but with no symbol of a town. However, at the same time, Phara appears as a strong and well-organized community in the narrative of Ammonius (Mayerson 1980; Caner 2010, 141–71). Unquestionably, the town was located at Tell Maḥrad, on the western end of the Feiran palm grove,98 where excavations by Grossmann (1996, 2000, 2007) exposed important Byzantine and Nabataean remains.

Another biblical name common in Nabataean inscriptions in this region is Qini/Qinw/’Ibn-al-Qini (קיני/קינו/אבנ-אל-קיני) and similar forms (figure 15) (see Starcky 1979, 38–39). It occurs 72 times in southwestern Sinai, mainly in the areas of turquoise and copper mines mentioned above, 40 to 60 km northwest of Paran (Starcky 1979, 38–39; Negev 1991, 9, 58). This is the same area around Serabit al-Khadem, where the name Qeni already appeared in the early second millennium BCE. Here, we find again the Qenite connection to the copper sources, in different periods. Unlike “Paran,” the Qeni-related names are also found elsewhere in the Nabataean sphere, but in lower numbers (Negev, above). All these inscriptions follow the common Nabataean characters and formulas (see further below).

Two Mountains

Two of the mountains above the Feiran Oasis bear religious interest. One is Jebel Serbal, a granite mountain, 2070 meters above sea level, steeply rising 1300 meters above the Feiran Oasis (figure 16). During the nineteenth century, several scholars visited the mountain.99 They mentioned Nabataean inscriptions and a stone mound next to the summit knob. Lepsius (1853, 532–62) dedicated a long discussion to it, identifying the mountain with the biblical Mount Sinai, as did Currelley, expressing Petrie’s opinion (in Petrie 1906, 251–4).

During my first visit to the mountain (in June 1979), I recorded several built elements just below the summit and 70 Nabataean inscriptions. Observing the stone mound (approx. 8 x 8 m, up to 1.1 m high), I noticed several clues indicating it was actually a ruin of a small Nabataean temple. A following dig proved this correct, and important finds were uncovered (Avner 2015, 398–405). One find should be mentioned here: a silver coin of ‘Abdat II, 30-9 BCE.100 As to the inscriptions, 20 were already included in the CIS II (Nos. 2104-2123), four were added by Negev (1971, Nos. 30-33), while others were catalogued by Stone based on photographs of myself and of others (see index in Stone 1994, 234). One inscription mentions the title אכפלא, i.e., high priest (figure 17).101 The temple was in use at least from the first century BCE to the third century CE (Avner, above).

Jebel Moneijah is lower, 1165 m above sea level, but also steeply rises 515 m above the Feiran Oasis (figure 18). Its full name is Jebel Moneijat Musa, i.e., “the mountain of Moses’ meeting” (with God), based on a Bedouin tradition perceiving Moses as the patron of herds and shepherds. In 1868, the summit was visited by Wilson and Palmer (1869, 213; 1871, 173–4), who described a Bedouin cult enclosure (today 5.5 m across and 1.5 m high, figure 19) where the Bedouins sacrificed to Moses and left votive offerings.102 Palmer copied 15 Nabataean inscriptions engraved on the enclosure’s stones (figure 20), but thought they were unimportant. Later, 17 inscriptions were included in the CIS II.103 These inscriptions contained a surprisingly large cluster of priestly titles: אכפלא/אפכלא- six times; מבקרא (sacrifice inspector) four times; one כהנא (priest); and one כתבא (scribe, figure 19). A few Nabataean pottery sherds collected around the precinct (by me) are dated between the first century BCE and the first century CE. However, one inscription is dated 219 CE,104 so this Nabataean sacred place was in use for at least 300 years, as was the sanctuary of Jebel Serbal.

In 1976, the site was visited by S. Levi and A. Goren, who added 13 inscriptions from the trail leading up to the summit, which were published by Negev (1977a). One inscription added one occurrence of the title אכפלא. Levi (1977; 1987, 396–7) described the Bedouin custom based on interviews with informants. In brief, once a year young shepherds (boys and girls) walked up to the precinct with their flocks to perform a ritual under the auspices of Musa (Moses) to ensure the herds’ fertility. In addition to the annual event, Bedouins from all southern Sinai used to undertake pilgrimage to the mountain during several holidays, as well as on private occasions. One man, Jum‘a, of the Feiran Oasis, was in charge of the enclosure and its maintenance.

During my three visits to Jebel Moneijah (twice in 1979, once in 1996), I was told that the ritual was still practiced (I did not manage to attend it, and at present, 2021, I have no information about it). In the precinct, beads, buttons, coins, and other small offering objects were found, mainly in a small niche in the southern wall. On the enclosure walls, the published inscriptions were visible and legible, but I also noticed others inscribed on stones incorporated within the walls. I was able to pull some out for documentation and place them back into the wall; others I could only partly copy from inside the walls. Hence, the walls may still contain more unseen inscriptions. Altogether, I counted 45 inscriptions in the enclosure alone and three more 7 meters to the southwest. Forty-four inscriptions could be read and they increased the number of אפכלא/אכפלא to eleven and מבקרא- to seven. Remarkably, Jebel Moneijah is the only site known to date in the entire Nabataean sphere with such a high number of priestly titles. No doubt the inscriptions, especially these with clergy titles, attest to a past Nabataean temple of greater importance than that of Jebel Serbal (where only one inscription bears a priestly title).

The position of Jum‘a, as described by Levi, recalls the title ביתיא (“in charge of the house”), mentioned in eleven Nabataean inscriptions in southern Sinai.105 The referred “house” is most probably a temple, similar to the “house” in a Nabataean inscription from Madain Saliḥ, northern Hejaz (Healey 1993, 34, 230). In the Bible, however, the title relates to the king’s palace (see below).106

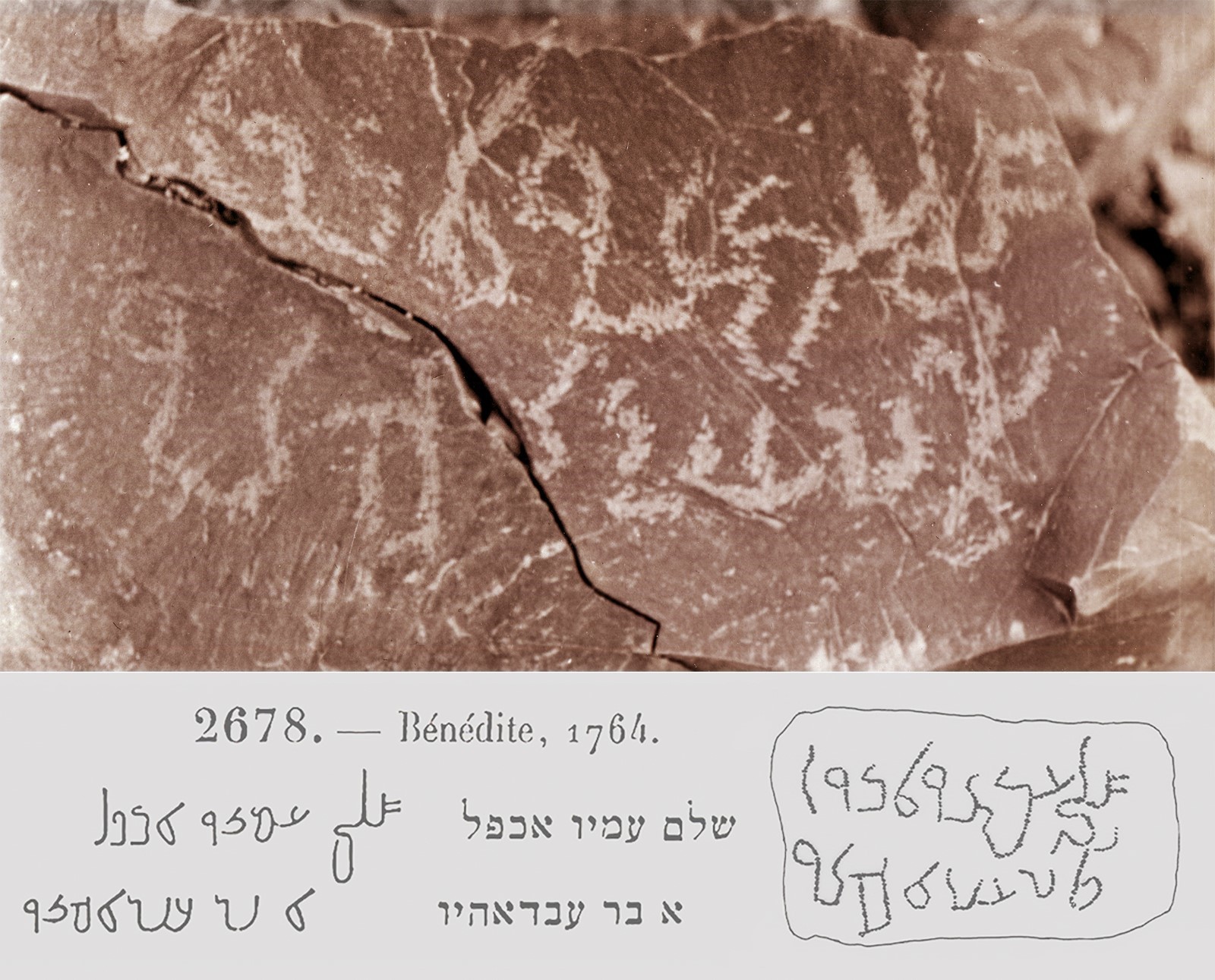

Nabataean Religion in Southern Sinai

The intensive occurrence of priesthood titles in southern Sinai, unparalleled in any other Nabatean territory, must attest to the religious importance of the region. On Jebel Serbal, Dushara, the chief Nabataean god, was worshiped (Avner 2014, 402). On Jebel Moneijah, the worshiped deity/deities is/are unknown, but the names of two priests mentioned in the inscriptions may yield a clue. One is גרמאלבעלי בר ואלת (“Garm-alBa‘ali son of Walat,” CIS II, 2678), the other—עמיו בר עבדאהיו (“‘Amiyw son of ‘Abd-Ahyw,” figure 21, CIS II 2678). Hence, three deity names occur here, alBa‘ali (=Ba‘al), Walat (=Alat), and Ahyw (=Yahw; Starcky 1979, 39–40; Zayadine 1990, 159–64). The name ‘Abd-Ahyw is a direct parallel to the biblical “‘Obadyahw in charge of the house” of King Aḥab (1Kings 18:3), to two occurrences of ‘Obadyahw in the ‘Arad ostraca (Nos. 10, 49, Aharoni 1981, 24, 80, the latter incomplete), to ‘Obadyw of the Shomron ostracon No. 50 (Reisner, Fisher, and Lyon 1924, 237, 242), and to ‘Obadyw at Kuntilat ‘Ajrud (Aḥituv, Eshel, and Meshel 2012, 76–77).

Besides Jebel Serbal and Jebel Moneijah, priestly titles and deity names occur in several other inscriptions in the same vicinity (CIS II:825; 969, 2188; Negev 1971, No. 33). The number of occurrences of the titles is אכפלא/אפכלא- fourteen times; מבקרא- eleven; כהן/כהנא- eighteen; כהנת (priestess) one; כמר (priest) one; ביתיא- eleven; כתבא- twice; and one עלימא (‘Alima), most probably in charge of a cemetery (Hebrew—בית עולם, Aramaic—בית עלמין). Fourteen other inscriptions mention—“(…) כהן (…)“ (“(…), priest of (…)”), with the name of the deity they served: al-‘Uzia, T’a, Alat, Bubak/kayubak (for details and references, see Avner 2015, 404–6). Altogether, 61 priestly titles occur in the Feiran area, compared to a total of only eight occurrences in the entire vast Nabataean sphere.107 In addition, priestly titles also appear in the Feiran area as personal names: seven times אלכהנו (al-Kahanw) and 102 times מבקרו/אלמבקרו (Mabqarw /al-Mabqarw).

Deities are also directly invoked by their names in inscriptions. Dushara is known only once in the Feiran area (CIS II, 2912), but three other inscriptions bearing his name were added by Stone and Avner from Wadi Shellal, 30 km northwest of the Feiran Oasis, where he is mentioned together with Al-Ba‘ali,108 who is also mentioned in CIS II 1479.109

Much interest is found in the frequency of Nabataean and non-Nabataean theophoric elements in personal names in the Sinai inscriptions:

| Inscriptions (Nabataean) | |

|---|---|

| Walat (Alat) | 18 |

| Algya’/Alga’ (‘Abd-alGya) | 10 |

| Dushara (e.g., Tym-Duahara) | 8 |

| ‘Abdat (e.g., ‘Abd-‘Abdat) | 6 |

| Ḥartat (e.g., ‘Abd-Hartat) | 2 |

| ‘Uzai/‘Uzia (e.g., ‘Abd-‘Uzia) | 1 |

| Shai‘a’ (‘Abd-Shai‘a’ ?) (?) | 1 |

| Total | (?46) 45 |

| Inscriptions (Non-Nabataean) | |

|---|---|

| alBa‘ali (Ba‘al) (e.g., ‘Abd-alBa‘ali) | 456 |

| Alahi (El) (e.g., ‘Abd-Ala’hi)110 | 278 |

| Ahyw (Yahw) (‘Abd-Ahyw) | 16 |

| ‘Anat (‘Anat-alhi) | 3 |

| Sarapius (Sarapyu) | 7 |

| Qos (Qos-‘adar) | 1 |

| Total | 761 |

Interestingly, the non-Nabataean gods outnumber the Nabataean ones by 16.5 times as theophoric elements in names.

Biblical Implications of the Nabataean Evidence

The finds from Jebel Serbal and Jebel Moneijah, especially the inscriptions, illuminate several points relating to the biblical narrative, despite the time gap:

-

The remarkable cluster of clergy titles, deity names, and theophoric elements in personal names around the Feiran Oasis indicates that during the Nabataean era and later, the region was exceptionally important religiously. Since the area is far from the Nabataean centers and from the trade routes with Arabia, there must have been another, specific reason for this religious importance. The only apparent source for this unique phenomenon is a deep, older tradition.

-

The predominance of non-Nabataean deity names, invoked or mentioned in the inscriptions (97.7%), and the predominance of non-Nabataean theophoric elements in names (94.3%), imply that the majority of the population in the Feiran Oasis, or even in southern Sinai in general, was autochtonic (see Starcky 1979). This population, much like other ethnic groups in the Nabataean sphere, assimilated into the Nabataean culture (see Graf 2004, 2007, 182), adopted Nabataean gods, but mainly adhered to its old gods. This was the very population that preserved the biblical geographical name of the region: Paran.

-

During the Byzantine Period (early fourth to early seventh centuries), the Christian monastery of St. Katerina was first built, and many smaller monasteries and laurae were established. The monks formed a sacred tradition around Jebel Musa, Jebel Katerina, the Feiran Oasis, and a number of other sites (Dahari 2000; Caner 2010; Ward 2015, esp. 52-4, 76-80). These monks could seemingly be the source for the present-day Bedouin tradition surrounding Moses. However, the strong religious character of the Feiran region is obviously pre-Christian. Therefore, the autochtonic population of the Nabataean time was the natural source for the early Christianity in Sinai regarding the tradition of Moses and the sacredness of the mountains (see Ward 2015, 70–91), as well as for the Bedouin tradition.111

-

Ahyw-Yahw was one of the old gods of this autochtonic population, who was still known and worshiped by some in the third century CE. His Nabataean spelling, and probably also pronunciation, was close to that of the aforementioned Ahiu/Ihiu in the Theban stela of Akhtoy, of the late third millennium BCE.

-

The religious importance of the Feiran area and its antiquity is further illuminated by the words of Diodorus, first century BCE: “(…) This region is called the ‘Palm Grove’ (Phoinikon) and contains multitude of trees of this kind, which are exceedingly fruitful and contribute an unusual degree of enjoyment and luxury (…). Moreover, an altar is built there of hard stone and very old in years, bearing an inscription in ancient letters of an unknown tongue. The oversight of the sacred precinct is in the care of a man and a woman who hold the sacred office for life.”112 The “ancient letters” mentioned by Diodorus could not be Greek, Egyptian, Nabataean, Thamudic, or Aramaic, which were all known in his time, so the remaining option for “very old” script is the Proto-Sinaitic, addressed above. Diodorus’ description strongly support the pre-Christian sacred tradition of the region.

- The Feiran Oasis and the two sacred mountains may have been the destination of the religious groups from Israel and Judah who travelled through Qadesh Barne‘a, Kuntilat ‘Ajrud, and Darb Sha‘ira. It could also be the route related to Elijah on his way to Mount Ḥoreb (1King 19). Truly, very few Iron Age remains are known to date in southern Sinai, but some can be mentioned. An unpublished survey of B. Mazar in 1957 on Tell Maḥrad (referred to by Rothenberg 1961, 166) mentioned the collection of pottery of the Iron Age II, the Persian and Hellenistic periods, numerous Nabataean sherds and pottery of later periods. In 1970 I found one rim fragment of an Iron Age II jar in Wadi Nefus, a northern tribute of the Feiran Oasis. In any case, an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and the words of Diodorus are certainly interesting in this context.

Summary

In the attempt to contribute some data to the ongoing debates, this article addresses two related issues, as indicated in the title. In my view, the desert roots in ancient Israel support the southern origin of Yhwh, while Yhwh’s southern origin illuminates the role of desert tribes in the formation of early Israel. Although the data presented here are not new, some were overlooked or underutilized in published analyses. Assembling the data from a variety of sources provides a broader picture of the desert’s history, of some aspects of the ethnogenesis of Israel, and of the origin of its God. In brief, the desert tribes brought their desert God to the “mixed multitude” of groups that gathered in Cana‘an, and under a covenant with this God created a confederation that later evolved to a nation (עם) named Israel (see Gottwald [1979] 1999, 693–9, 705–10; Stager 1989, 142–51; Mendenhall 2001, 77–81).113

The aforementioned three groups of sources, biblical passages, Egyptian texts, and the Kuntilat ‘Ajrud inscriptions, associate Yhwh to the desert (Se‘ir, Sinai, Edom, Paran, Ḥoreb, Teman, and Qadesh) and form a consistent attestation to his southern origin. The late third millennium BCE Egyptian text relating Ahiu to copper mining in southwestern Sinai, and its identification with Yhwh, are only probable, but they gain some support from additional sources. Identification of the Paran Desert in southern Sinai seems conclusive, based on the perpetuation of the name in many Nabataean inscriptions in the Feiran region. This concurs well with the additional data: the geographical connection of southern Sinai with Kuntilat ‘Ajrud, the unique religious lore of the area, and the persistence of the Moses tradition among the present-day Bedouins. This does not mean that Jebel Moneijah or Jebel Serbal should be identified as Mount Sinai, which many explorers and scholars attempted to locate, not only in Sinai. It would be enough to say that southern Sinai could be the source of important elements in the Exodus narrative and in the formation of the Israelite collective tradition.

The deep desert roots in the culture of Israel cannot be fictive; they must reflect the people’s notions and a reality. Seeing Israel as a “mixed multitude” of ethnic groups gathering from various origins (Egypt, Mesopotamia, Anatolia Cana‘an, Transjordan, Se‘ir, Mediterranean islands) means that a long formation process was needed to solidify the nation. Naturally, during this process, each group strived to influence the others from its own culture (as occurs in modern-day Israel), including through conflicts. This is the reason why the Bible, even after Deuteronomistic and Priestly editions, still contains several different theologies (see, e.g., Zevit 2001; LaRocca-Pitts 2001; Avner 2006), again, much like today. In this cultural competition, the desert groups, the Shasu, managed to gain the strongest influence on Israel’s social framework, on its law, and most of all on its spiritual culture. Hence, the desert tribes were probably a ‘core group’ in the forming nation.114

Introduction of Yhwh into the Land of Cana‘an/Israel by the desert tribes should not be underestimated, since the worship of other gods was well established long before his arrival.115 The success of the Shasu in introducing their God is demonstrated by the dominance of the theophoric elements Yahu, Yah, and Yw in personal names in Judah and Israel. A study of Mitka Golub (2017) collected Hebrew names from the books of Kings and Chronicles, and from epigraphic finds, i.e., ostraca, inscriptions, seals, and seal impressions. Out of 511 names, 430 contained the Yahwistic theophoric elements, while only 81 names contained El. Yahwistic names took 84%, against only 16% of names containing El, despite the fact that El was worshiped in Cana‘an long before Yhwh and was also the God of the Patriarchs.116 Another study, by Golub (2019), demonstrates a sharp increase of Yahwistic names from the United to the Divided Monarchy. These data represent the growing dominance of Yhwh throughout the first temple time, as also deduced by several scholars (e.g., Lemaire 2007; Römer 2015) before having the updated data of Golub.117

One possible problem remains. Yahwistic names became common in the Bible only in the tenth century BCE (e.g., de Moor 1990, 13–20, 32–33), approx. 350 to 200 years after the mention of “the Shasu land Yahu” in Egyptian topographic lists and of Yah in the Book of the Dead. These names occur in lists of high officials of King David (2 Samuel 8:16-18, 20:23-26) and of Solomon (1Kings 4:2-7), lists that seem to be quoted from authentic official documents such as “the book of the acts of Solomon” (1Kings 14:41).118 In presently known epigraphic finds, Yahwistic names first occur even later, around 800 BCE (Golub and R. 2017, 36, 2019, 58, Note 7, and personal communication). However, since only 12 Hebrew names are known to date from epigraphic finds before that, this difficulty may not be significant.

The desert people were certainly inferior to those of the sown lands in material culture and economic resources. Therefore, their ability to influence the others in the spiritual sphere is remarkable. Studying prehistoric cultic remains in the desert (maṣṣeboth, open-air sanctuaries, burials, and mountain cult sites) exhibits the same result in each: the desert inhabitants appear as creative vanguards in theological-philosophical ideas (Avner 2018). What was their source of power? A possible brief answer is that the desert environment combined two different impacts on humans. One is the primordial beauty and vastness of the desert landscape, which served as a source of inspiration; the other is the hardship. Desert people lived with a high degree of uncertainty, particularly with regard to rainfall.119 Therefore, they were more dependent on the forces of nature, i.e., on gods. This motivated them to intensive religious activity, which led to religious creativity and thereby to an established religion that empowered them to influence others in this domain.120

As mentioned above, the desert lore in ancient Israel could not be merely the outcome of a 40-year desert sojourn, nor the result of the Israelites’ exposure to the desert during the eighth century BCE or the invention of a late redactor. To some extent, the prehistory of the desert was also the prehistory of Israel - an observation that should encourage further studies.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to friends and colleagues who sent to me their publications, referred to in this paper (when libraries were closed due to the coronavirus) in alphabetic order: Niv Alon, Nissim Amzallag, Clinton Bailey, Erez Ben-Yosef, Elizabeth DeGear, Avraham Faust, Israel Finkelstein, Orli Goldwasser, Mitka Golub, David Graf, Liora Horowitz, Ann Killebrew, Tom Levy, ‘Amiḥai Mazar, Tryggve Mettinger, Racheli Shlomi-Ḥen, Michael Stone, Pierre Tallet, Orit Shamir, Kenton Spark, Na‘ama Sukenik, Juan Tebes, Peter van der Veen and Na‘ama Yahalom-Mack. Some of them read the draft and made important comments. I am also grateful to two anonymous readers for their comments. Thanks to Alfonso Nusbaumer, Winnie van der Oord, and Yonel Sharvit, who helped me in reading French and German publications, and to Rina Avner and Michelle Finzi for checking the English of the Manuscript. I also thank the staff of the IAA library in the Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem, the main library that I was using. Photographs are of mine, unless otherwise is stated, maps and drawings were also made by me, with the assistance of Raḥamim Shem-tov.

References

Abdel-Motalib, A., M. Bode, R. Hauptmann, U. Hartung, A. Hauptmann, and K. Pfeiffer. 2012. “Archaeometallurgical Expeditions to the Sinai Peninsula and the Eastern Desert of Egypt (2006, 2008).” Metalla 19: 3–59.