Before God: Reconstructing Ritual in the Desert in Proto-Historic Times

Archaeological remains are a trove of potential data which, together with the study of ritual, enable reconstruction and evaluation of social and religious structures and complexity. Concentrating on the Timnian culture (sixth to late third millennium BCE) of the Southern Levant deserts, we review the changes that took place with the adoption of the domesticated goat, noting the contrast between habitation sites and ritual related megalithic monuments regarding social hierarchy. Desert kites, open-air shrines, and cairns reflect organized communal labour and use, reinforcing tribal identity and the need for territorial definition. The orientation of the open-air shrines reflects a cosmology related to death and mortuary. Timnian Rock art comprises geoglyphs and petroglyphs. Geoglyphs are associated with open air shrines while petroglyphs represent a slightly later development initially unrelated to ritual. In accordance with the rock art repertoire and styles employed, we suggest that the orant was integrated into the Timnian culture following contact with northern cultures by way of trade with Arad. Rock art also highlights foreign entities in the Negev during the Intermediate Bronze age.

Timnian culture, ritual, open-air sanctuaries, cairns, rock art, Negev

Introduction

In any specific society, cosmologies and belief systems are, of necessity, integrated with other social, economic, and political structures of that society. Anthropology has established a firm database which exemplifies how religious structures grow out of the society, reflecting the social structures. These are interwoven, as the economic base and environmental conditions affect population density, which, in turn, relates to group formation and social complexity. These factors may also be traced at the level of cosmological hierarchy developed. Thus, Hultkrantz (1966, 145) points out that:

The religious structure reflects the social structure which in some respects fulfils ecological demands. In an ecological situation which does not allow population density and complicated group formations there is no place for an elaborate stratified society, and thus no possibility of the emergence of a hierarchical priesthood. Collective rites of a fixed and elaborate character appear above all in societies where ecological and technical circumstances motivate joint efforts in economic enterprises. True temples with daily attention to the symbols of the gods exist only in cultures where permanently resident groups have formed as a result of ecological (and technical etc.) opportunities. Beliefs and myths reflect the social and religious structure built on ecological premises.

Archaeologists studying extinct cultures cannot observe belief systems, but work with material remains as the consequence of actions (or lack thereof) which may be interpreted as arising from religious beliefs (Renfrew 1985, 12). Ritual is a time-structured performance of fixed sequences of actions with prescribed repetitions and assigned durations. Places where ritual is performed may also be places of assembly and therefore may be seen as foci of social networks (Renfrew 2007; Kyriakidis 2007b). Repetition increases the likelihood that physical remains may form patterns recognizable in the archaeological record (Marcus 2007). Not all ritual is religious, and it may be difficult to differentiate between specific rituals. In addition, sacred and mundane rituals, with their associated activities and remains, are often intertwined. Renfrew (2007, 115) lists four main points which may help recognize sacred ritual and cult practices: 1. Attention focusing; 2. special aspects of the liminal zone; 3. presence of transcendence and its symbolic focus; and 4. participation and offering. In the ‘From Archaeology to Society’ section of this paper, we draw on these four points to reconstruct and speculate on aspects of Timnian religion in the proto-historic periods of the southern Levantine deserts.

To better understand the social structure of a society, we turn to the habitation and settlement systems, including material culture organization, which mirrors it. These systems then serve as a base from which to assess the society and with which the religious structures must be in accord. Following this concept and concentrating on the archaeological record of the mobile pastoral Timnian societies of the southern Levantine deserts, we can detect and trace some of the evolution that took place in the culture, belief systems, and cosmologies (Rosen 2015). Here we will outline two aspects; the first relates to the degree of social complexity as expressed through the settlement plans and ritual sites, shrines1, and cairn fields. The plan of these, their form of construction, and their spatial setting reflect an overall Timnian culture with public, communal ritual related to mortuary practices. The burial cairn fields acted as foci for ritual, and also served as territorial markers and cultural symbols. The second aspect is change and continuity in Negev rock art. The rock art developed relatively late in the Timnian sequence alongside or following the later phases of the open-air sanctuaries and cairn construction; it played a small role in Early-Middle Timnian ritual. The rock art helps us complete the picture of the Late and Terminal Timnian phases as it expresses an enduring tradition with an emphasis on male ibex. Through the rock art, we are able to recognize foreign influences and presence in the Negev during the final phases of Timnian culture.

Timnian Chronology and Culture

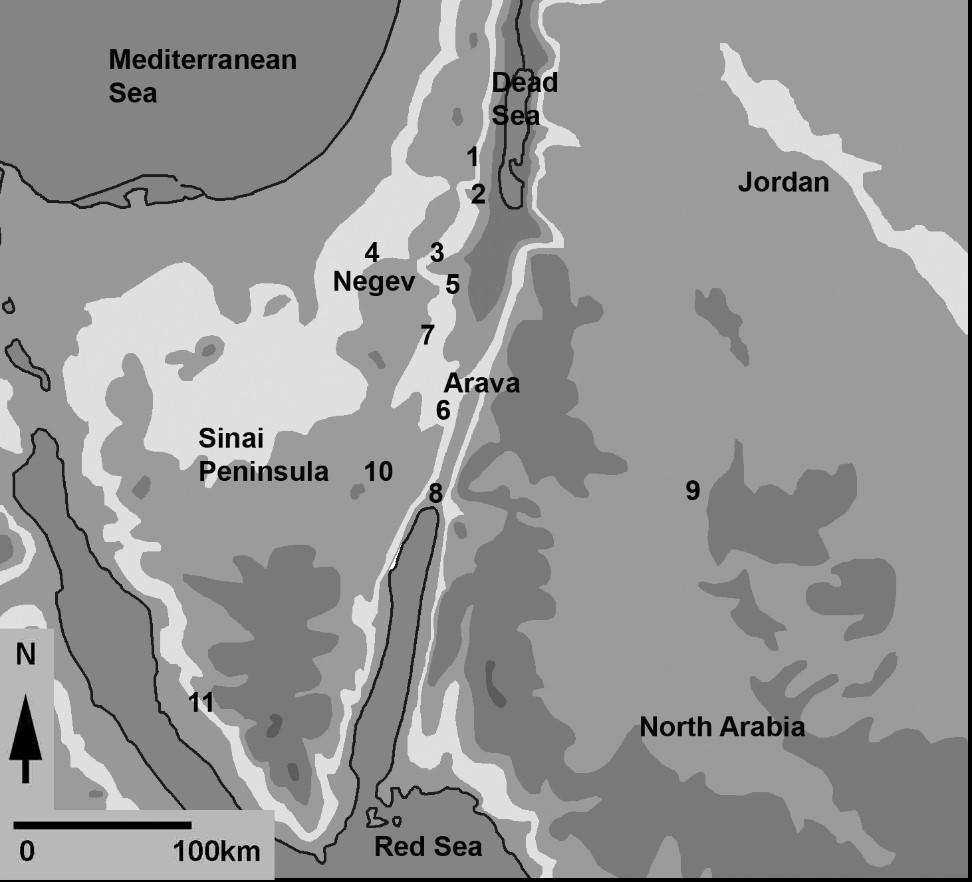

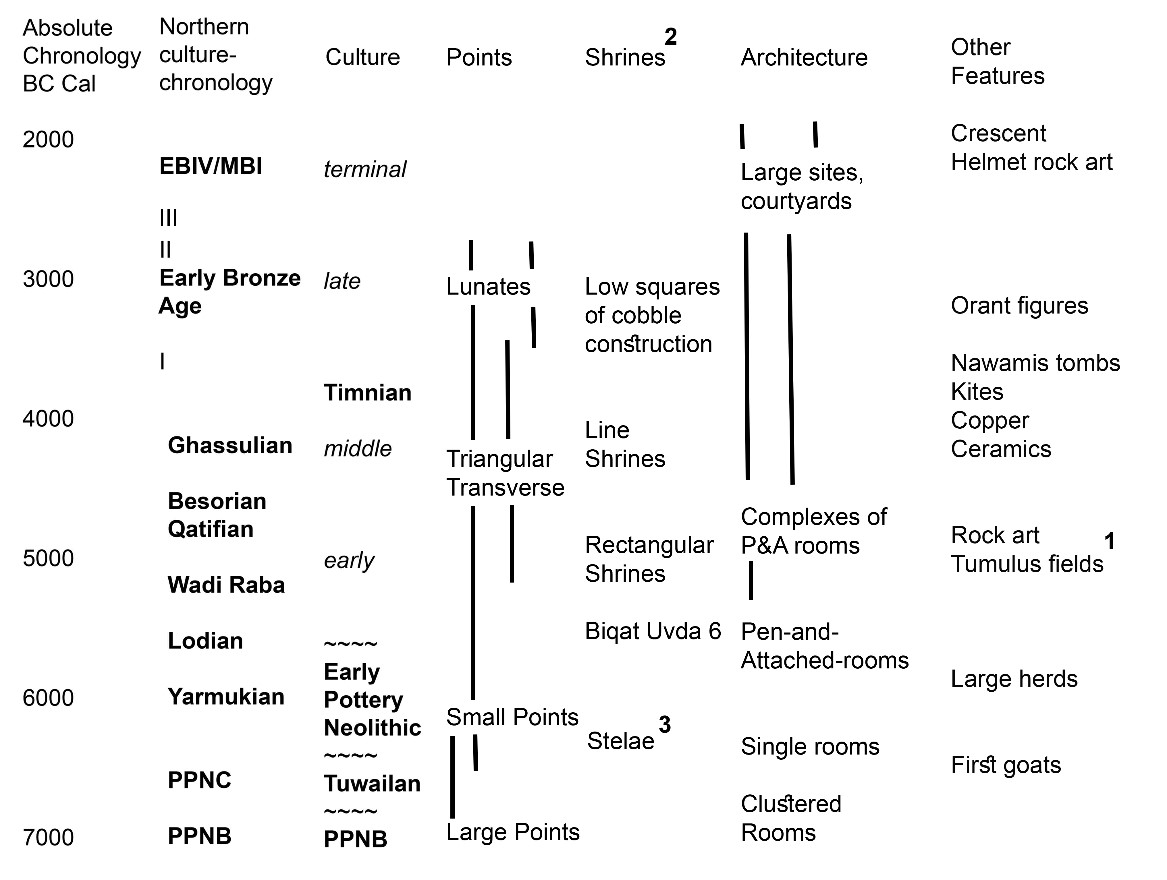

The adoption of the domestic goat and the gradual shift to pastoralism brought deep changes to the southern Levantine desert cultures in southern and eastern Jordan, the central and southern Negev, and in central and southern Sinai [Figs. 1, 2]. These changes may be traced through domestic, mortuary, and ritual architecture as well as material culture. This new cultural entity, the Timnian, spanned over three millennia, from the sixth to late third millennium BCE (Rothenberg and Glass 1992; Rosen 2011). In it we see the first period in which herds were integrated into the matrix of desert culture, as well-reflected in a transition in the basic architectural unit (Fujii 2013; Rosen 1988). The architecture of Early Timnian habitation sites (e.g., Be’er Ada (Goring-Morris 1993); Xasm Attarif and Ath Thamad (Kozloff 1981); El Qaa (Phillips and Gladfelter 1989), and, slightly later, al-Thulaythuwat sites (Abu-Azizeh 2013); see Fujii (2013) for sites in southern Jordan), is distinctly different from the preceding Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) interlocking beehive structures (Gopher and Goring-Morris 1998; Goring-Morris 1993; Tchernov and Bar-Yosef 1982). In the Early Timnian, the beehive or clustered plan was replaced by round enclosures with a number of attached stone hut bases (Goring-Morris 1993; Kozloff 1981; Rosen 1988, 2011). The rooms are more dispersed than the PPNB clustered huts, suggesting that social interactions changed, focusing on the centrality of the herds. The ‘pen-and-attached-rooms’ architectural tradition continued through the different Timnian phases into the Terminal Timnian, though by this time additional architectural traditions co-existed in the region. Notably, later desert architectural traditions again changed form (Rosen 2017, 218–37).

Material culture composition changed over the span of the Timnian phases, reflecting a distinct, locally developed desert tradition of ceramics and lithics (Rothenberg and Glass 1992; Rosen 2011). One expression of this is seen in the decrease in large blade-based arrowheads, replaced by small point and transverse arrowheads, paralleling a similar transition in the settled zone. Other changes include tabular scrapers, which replaced the tabular knives (bifacial knives, tile knives, etc.) characteristic of the earlier Tuwailan culture (Goring-Morris, Gopher, and Rosen 1994). The production of tabular scrapers increased through the Late Timnian (Abe 2008, 530–36).

Hunting did not cease with the emergence of the pastoral Timnian, but as goat and sheep husbandry took root, it ceased to play the primary role in subsistence that it had played in previous periods. Communal gazelle hunts were carried out in desert kites, the meat acquired likely to be more than what a few individuals would be able to consume. After trapping/hunting was completed, the animals would need to be butchered, transported to a site for further preservation, or prepared for exchange (Bar-Oz, Zerderb, and Holec 2011). The kite required the organization of labor for construction and operation, indicating a social structure enabling investment and longer-term planning. The kites likely imply corporate ownership (Rosen 2017, 163–64). Some of the earliest desert kites (found in northeastern Jordan and eastern Syria) have associated rock art depicting either animals or desert kite formations with or without human and animal figures (Cauwe et al. 2004; Betts and Svend 1986; Helms and Betts 1987). At present, a few desert kite depictions are known from the Negev and Sinai but are not associated with a specific desert kite site and likely date to a slightly later period than that of the kite construction (Eisenberg-Degen 2010; Hershkovitz et al. 1987). There are two points to consider here. First, given the dominance of domestic animals in desert faunal assemblages (Horwitz 2014) and large rock shelters with clear evidence for large herd stabling of goats (Rosen et al. 2005; Landau et al. 2020), we suggest that hunting, by the late fifth millennium BCE, should be viewed as a social ritual, a prestige-related activity. In the Late Timnian, animals from domestic herds were eaten sparingly while, perhaps, the use of desert kites and the hunting of wild animals were for feasting. In the virtual absence of rock art depictions of domestic herd animals (i.e., goats and sheep), hunting and using desert kites would seem to reflect status and prestige, and the depictions as reflections of special ceremonies and events, and not everyday activities.

The Middle Timnian shows continuity from the Early Timnian. Existing cairns and open-air shrines continued to function. The structures were added to already existing shrines (see below), and additional cairns were constructed. The first nawamis, a new tomb form containing burials with a unique and elaborate material culture, appear in this period, the late fifth and fourth millennia BCE (Bar-Yosef et al. 1977, 1986).

In the Late Timnian, the domestic economy of this desert society expanded to include small-scale cottage industries, including the production of grinding stones, beads, tabular scrapers, copper production, transport of bitumen, and the trade in trinkets (Abadi and Rosen 2008; Beit-Arieh and Gophna 1981; S. A. Rosen 2003; Rothenberg and Glass 1992), all intended partially for export. As exchange intensified, so did the dependence of the desert people on the settled zone (Rosen 2017). In this period, a new architectural type, based on square or rectangular broad-room, appears in the desert, supplementing the pen-and-attached-room type. Petrographic analyses of vessels from the site of Arad in the northern Negev, ‘Aradian’ sites with broad-rooms in southern Sinai, and Late Timnian sites in the Negev, provide evidence for contact and the movement of pottery between regions (Amiran, Beit-Arieh, and Glass 1973; Porat 1989). The functional configuration of the ceramic assemblages at Arad and at the broad-room settlements in southern Sinai were found to be similar, while pastoral sites lacking broad-room architecture exhibited lower levels of diversity and higher relative proportions of whole mouth vessels (Saidel 2011). The broad-room structures, the pottery assemblages, and the presence of imports from the north are evidence of a second, separate population living alongside the Timnian culture (Beit-Arieh 1986). The broad-room sites are directly tied to the development of Arad, as a gateway city to the desert (Amiran, Ilan, and Sebbane 1997), and the growing trade with the Negev and southern Sinai. Rothenberg and Glass (1992) recognize these structures and their associated inhabitants as trading stations and traders. The increasing diversity in cottage industries was specifically a Late Timnian phenomenon, but it can be tied to the expansion of the Aradian system (Rosen 2017, 188–98).

A different approach formulated by Finkelstein (1990) sees the Early Bronze town at Arad as a settlement of sedentarized desert nomads. Differences between the architecture of Arad and its satellite sites, as reflected in the Aradian broad-room house and that of the desert pastoral encampments with the enclosure and attached room structures, as well as significant material culture contrasts, do not support this claim. For example, Arad was agriculturally based and the sickle blades in use were of the northern, Canaanean technology, and tied to a specialized production and distribution network (Milevski 2013; Rosen 1997, 106–11; Manclossi, Rosen, and Miroschedji 2016), contrasting with the (few) desert agricultural settlements with local sickle blade technology (Rosen 2013). Ceramic production at Arad reflects diversity and specialization with the use of “northern” technologies well beyond the level of desert cottage industries.

Four settlement types (Cohen 1999; Haiman 1996) are noted in the Negev Terminal Timnian, chronologically equivalent to the Intermediate Bronze age (=EBIV, Middle Bronze I, and EB-MB). Generalizing, the site-types are classified as:

-

Typical Timnian architecture with a pen and number of attached rooms. These sites are usually located some kilometers from a water source;

-

Sites with attached rectilinear broad or elongated rooms with supporting columns, such as Har Yeruham and Har Tzayad;

-

Large sites, such as Nahal Nizzana, with clustered insulae of irregularly shaped rooms and court yards; and

-

Sites with complexes of round stone huts and small courtyards (Cohen 1992; Cohen and Dever 1979). The huts have one or two central supporting stone pillars. Some sites consist of a few isolated hut complexes while others may number dozens of clustered complexes with hundreds of rooms. Some sites exhibit different architectural traditions within the same site. The major sites, such as Ein Ziq and Beer Resisim, each span several hectares and are strategically placed near water sources and along trade routes. The ceramic assemblage of these sites presents a new tradition with wheel finished vessels alongside a percentage of vessels made only by hand with a red and ‘wild’ burnishing (Cohen 1999, 84–237; Roux and Jeffra 2015).

Copper ingots, weapons, tools, and worked shell were noted at various sites (Cohen 1999, 84, 260; Saidel 2002). All the sites chronologically correspond to the Terminal Timnian/Intermediate Bronze Age, although some of the site plans and material culture indicate a ‘foreign’ settlement plan, culture, agenda, and technical know-how (Cohen 1999, 84–237). The economy of all these Negev sites was dependent on goat and sheep husbandry to a degree (Cohen 1999, 280; but see Dunseth, Finkelstein, and Shahack-Gross 2018 for the idea of provisioning).

Negev Rock Art in the Late and Terminal Timnian and Intrusive Iconography

The development of contact and trade with Arad in the Late Timnian, and the presence of a new people and culture in the Negev in a period corresponding to the Terminal Timnian, is also reflected in the rock art.

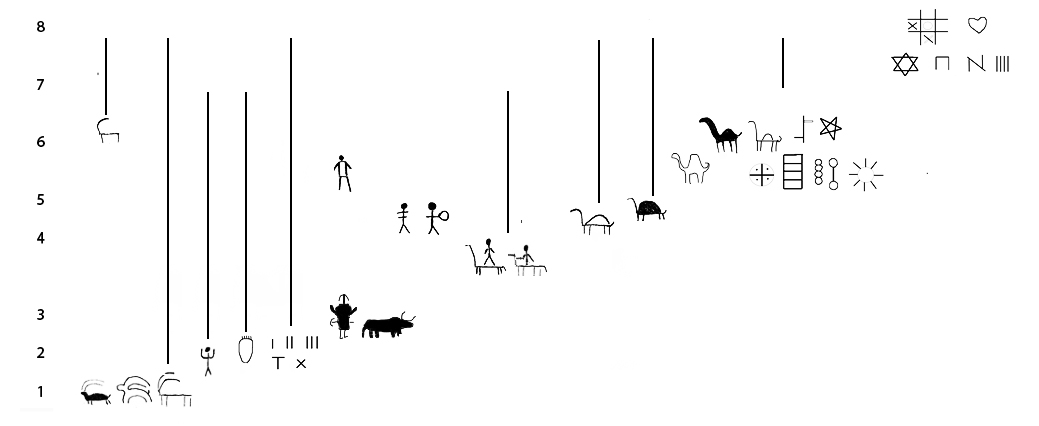

The Negev rock art tradition is characterized by a preference for dark, patina-covered surfaces. The repertoire consists of three major categories: abstract, zoomorphic, and anthropomorphic elements (Fig. 1). A relative chronology of Negev rock art has been constructed using superposition of motifs and relative shades of patina (Fig. 2). Specific chronological anchors, such as inscriptions, the introduction of the camel, etc., link the art to specific and dated periods (Eisenberg-Degen and Rosen 2013). The Timnian rock art complex served as the base on which the rock art of following periods developed, integrating new motifs and styles. Development in depicted motifs, and especially in the spatial use of the panel, can be noted over time. The earliest Negev rock art, possibly dating to the Middle Timnian, consists primarily of outlined or full-bodied ibex with two or four legs, usually in small dimensions. Other Middle Timnian rock art may include an anthropomorph and ibex set in the centre of a panel, and pairs of ibex followed by a predator. The date of the appearance of these motifs in the rock art has yet to be properly established. Goats, and perhaps sheep, the economic basis of Timnian society, are not represented in any of the Negev rock art phases, while the ibex is one of the most common motifs. Gazelles, hartebeests, oryxes, and oxen are present in only small numbers, if at all.

The increased production of rock art over the Late and Terminal Timnian, with clear preference for the male ibex and hunting scenes, can be seen as a reflection of changes which took place within the society. The long transition into a herd-based pastoral society brought on inevitable changes in perceptions of landscape, divisions of labor, and gender roles. Caring and living with goat herds, likely composed of a majority of female goats, redefined the relationship with wild animals. Late and Terminal Timnian ibex and ibex hunting scenes may reflect acts to maintain the symbols of the group, or they may constitute a relict of the changes they underwent (Eisenberg-Degen and Nash 2014).

The human gesture of upraised arms bent at the elbows with the palms facing outwards is usually interpreted as a dancing or praying position (Garfinkel 2003, 32; Maringer 1979) and termed orant. Orant figures first appeared in European Upper Paleolithic mobile art and have remained in consistent use throughout nearly all the late prehistoric periods in Europe (Maringer 1979). Examples of orant appear in Neolithic sites in Northern Israel (Garfinkel 2003, 118–231), but seem to have reached Egypt, southern Israel and Jordan only in the Early Bronze Age, i.e., the Late Timnian (Beit-Arieh 2003, 425; Ben-Tor 1977, 1985, 1991; Yakar 1989). Orant figures seem to have been introduced into the Late Timnian rock art as they do not appear in the oldest engraving phases. In isolated cases the orant is ithyphallic and juxtaposed with ibex motifs. The orant and orant/ibex motifs are loaded with religious connotations. Recognizing the introduction of the orant into an existing repertoire and existing tradition, we suggest that it ‘infiltrated’ with the people of the Early Bronze Age II broad-room house tradition, with people who either originated from Arad and integrated into the local community, or people closely associated with Aradian culture. Notably, Finkelstein (1990) claimed that the orant image originated in the desert and ‘traveled’ north, in contradiction to clear evidence that the orant image was in use in Mesopotamia much earlier that in the Southern Levant.

A second aspect of Aradian cultic iconography, though missing from Negev rock art, is the bull. Only a few cattle bones were recovered from Early Bronze Arad (Beck 1995), yet the bull image was integrated into the ritual realm, as evident from the bull statue found in the vicinity of the temple complex (Amiran 1972). The bull was one of the typical cult symbols not only within Arad but in Early Bronze Age II-III cities in Israel generally, contemporary with the Late Timnian (Bar-Adon 1962; Beck 1995; Callaway 1974; Cleveland 1961; Garstang 1967; Getzov 2006, 95–96; Sussman 1980). The bull was also a powerful symbol in Proto-Dynastic Egypt (contemporary with Early Bronze Age I, Late Timnian), often used to depict the goddess Hathor and the kings of the period (Yekutieli 2002). And yet, in spite of the increasing economic integration between the settled zone and the desert, the bull is absent from Late Timnian (Negev) rock art, and the dominant symbol remains the ibex, continuing from earlier phases of the culture complex. In this we see the clear separation of the northern and southern cultural realms, and the cultural continuities within the Negev.

It is difficult to discern chronological changes in Negev rock art within the Timnian sequence. Ibex continue to serve as the main motif, although unlike the early styles, in the late phases of the Timnian the figures were usually depicted in a linear fashion. In general, a consistency of technique, dimensions, repertoire, iconography, and panel type define Timnian Negev rock art, and by the Terminal Timnian, Negev rock art was well established in its basic configuration. Its use, purpose, and meaning can be debated, but it is clear that the rock art, in its form and placement within the landscape, reflects aspects of the society, including gender roles, cosmology, social structure, and various levels of identity (Eisenberg-Degen and Nash 2014). Given this basic cultural integration, foreign entities (in addition to Aradian outposts) may be detected within the rock art. Schwimer and Yekutieli (2017, 2021) identified a unique set of panels presenting complex scenes with a distinct iconography and the use of a new style. The scenes differ in complexity, with some including anthropomorphs of different sizes engaged in a group activity, many armed with crescent-shaped pommel handled daggers and recurved bows or held implements. The anthropomorphs are presented standing or kneeling, with a finely pecked, full hour-glass shaped body. Some have a distinct, crescent-shaped headdress ending with a plume. The ‘crescent-headed people’ appear with a particular set of finely, fully pecked zoomorphs, including lions and bulls. The ‘crescent-headed people’ panels are located along routes connecting copper mines and smelting sites with the central sites of the Intermediate Bronze Age, such as Ein Ziq and Beer Resisim. This entire phenomenon is present for only a brief time span in the rock art. Thus, the style, formation, and complexity of the ‘crescent-headed people’ scenes and images stand in contrast with the indigenous Timnian rock art that preceded it.

To evaluate the role rock art may have played in aggregation sites and communal rites, we may look at the dimensions and placement of panels. Negev rock art motifs rarely exceed 20 cm in dimension. The most common panel type is a smooth surface, usually a patina-covered limestone boulder. Although a few large panels are set with a natural ‘viewing area’, these cannot accommodate more than a handful of people, who even then would have trouble discerning the details of the rock art. Thus, in contrast to rock art in some places in the world (Ross and Davidson 2006; Sognnes 1994; Whitley 2005), it is unlikely that Negev rock art played an active role in communal rituals or rites.

Open-Air Shrines, Geoglyphs, and Cairns

Some two hundred ‘sacred precincts’ are attributed to the Early and Middle Timnian in the southern Levantine deserts (Avner 2002, 99–104; Fujii 2016; Goring-Morris 1993; Rosen 2015; Rosen et al. 2007). Early and Middle Timnian ritual architecture consists of outlined or filled square, rectangular, and trapezoid shapes (Fig. 1). Based on differences in dimensions and morphology, archaeologists have defined open-air shrines, platforms, ‘Jacob’s ladders,’ and lines (Israel and Nahlieli 1998). Some of these were constructed as part of a ritual, others served as focal points of ritual or as places where ritual was carried out; their religious meaning is less clear.

The terminology used does not necessarily reflect the use or level of importance that one form had over another. The oldest dated open-air sanctuary is the site of Biqat Uvda 6, with a mid-sixth millennium BCE date. This unique shrine consists of a roughly square shaped courtyard (11 by 12 m) orientated towards cardinal points of the compass with a single roughly rectangular room, or cell, attached diagonally to its western corner. The courtyard walls are built of two rows of stones, a single course high. Sixteen small field stones were found in the center of the cell, protected by four large boulders. East of the courtyard are 16 zoomorphic geoglyphs, 15 leopards, and a single antelope.

Geoglyphs have thus far been found in Southern Levantine Deserts only in association with open-air sanctuaries. They comprise geometric and zoomorphic elements. Most of the zoomorphic representations have been identified as predators, leopards, lions, or hyenas with few depictions of oryx, ibex, and gazelle (Avner 2002, 114; Yogev 1983). Geoglyphs excavated at Awja 1, in Jordan, have identical features to those of Biqat Uvda 6 (Fujii 2013), though the adjoining open-air shrines present different plans, none of which have parallels in the Negev. The Hashem al Tarif geoglyphs present a slightly different style from the Biqat Uvda 6 geoglyphs, but the adjoining open-air shrines and accompanying instillations are similar to those recorded throughout the Negev (Eddy and Wendorf 1999, 67–75; Miller 1999; comparing to Rosen et al. 2007; Avner 2002, 109–4). This suggests both underlying cultural ties between the people of the Southern Levantine Deserts and the existence of regional entities.

Based on the sequence noted at Ramat Saharonim dating to the late sixth millenium BCE (Porat et al. 2006; Rosen et al. 2007), the Negev open-air shrines, post-dating Biqat Uvda 6, consisted of a rectangular courtyard (approx. 22 by 10 m) with a ‘cell’ or installation sometimes constructed in the center of the more massive western wall. An additional evolution in open-air sanctuaries took place at some, still undetermined time, later in the Middle or Late Timnian, with the addition of secondary square (8 to 10 m) structures built north of the primary rectangular shrine (Rosen et al. 2007). The shrines developed from single rectangular structures to pairs of structures, a rectangular one and square one, north and slightly set back, with a rounded installation in its center. The addition of the square-shaped structure is common throughout the Negev. At some sites, such as Har Tzuriaz (Galili, personal observation), it is possible to identify a longer sequence of use and alteration (Fig. 3). Looking at the concentration of open-air shrines and other ritual-related architectural remains on the plain of Har Tzuriaz, it is possible to piece together the local development (though yet to be grounded with absolute dates). The sequence seems to consist of the construction and use of a rectangular shrine with a thick, western wall constructed of limestone blocks with a dark patina. The adjacent courtyard is defined by two rows of light-colored, large limestone cobbles. Following these constructions, two squarish shrines were added to the north of the rectangular shrine. These, with no particular wall emphasized, have a small, rounded installation set in the center. At some stage, a round built-up installation (six courses high, approx. 70 cm high) was added in the center of one of the square shrines and another within the rectangular shrine, slightly overlapping and covering the western wall. A large boulder bearing rock art set within a separate, rounded structure of indeterminate character (a dismantled cairn?) may reflect one of the final stages of use and recognition of the area as ritual within the Timnian sequence, although the presence of an open-air mosque a few dozen meters away indicates a continued sanctity of place. Such shrines, from the rectangular type often through the entire developmental sequence, are found in clear association with cairn fields in many areas of the Negev, the shrines built on the plain at the base of the hills and ridges on which cairns were constructed.

At other sites, elongated walls (5–11 m by 0.5–0.8 m) and large elongated wall/platforms (16–20 m by 3–6m) were noted in association with cairn fields in the Negev, often within the field and between the cairns (Galili 2019; Haiman 1992). A similar concept is seen in southern Jordan, where a different form of rectangular and trapezoidal platforms (either outlined or filled with stones, 3–11 m by 8–22 m) were likewise found in association with cairns fields, usually set east of a cairn (Abu-Azizeh et al. 2014). These seem to postdate the rectangular open-air shrines. The activities carried out in the open-air shrines, on or near the platforms or walls, would have been visible to anyone present. The aspect of mystery, rites known only to the religious leader and performed in sacred precincts to which the access was limited, seems to be missing from the Timnian ritual, as open-air shrine walls were low, and any activity carried out within or around the shrine would be visible to all. Such aspects of secret cult, confined rooms, and esoteric knowledge are common in the more northern sedentary and urban religions, perhaps reflecting greater levels of religious hierarchy.

The cairn field at Ramat Saharonim (Rosen et al. 2007) consisted of cairns with large stone ring bases, each with an oval or polygonal cist lined with stone slabs. The excavated cairns had skeletal remains and indicated repeated visits, additional burials, and rearranging of bones. The few grave goods consisted of pierced conus shells. The 30 Ramat Saharonim cairns were constructed along two parallel cliffs, and four pairs of open-air shrines are set in the ‘corridor’ between them (Rosen 2015). The cairns were dated to the late sixth/early fifth millennium BCE and chronologically overlap with the open-air shrines. Additional cairns have been dated to the Early and Middle Timnian (Abu-Azizeh et al. 2014, 164; Saidel 2017); Avner (2002) has indicated a similar date for the Eilat cemetery, although these dates do not derive from the interments themselves. The relationship between open-air sanctuaries, rectangular and trapezoidal platforms, and cairns was noted with different regional expressions in Sinai, the Eastern Negev (Galili 2019), Southern Jordan (Abu-Azizeh et al. 2014), and Northern Arabia (Fujii 2013; also see Abu-Azizeh 2013; Knabb et al. 2018; Rosen 2017, 119; Avner 2002, 114). For example, 28 of 32 cairn fields documented in the Eastern Negev had associated open-air shrines, installations, platforms, courtyards, etc. Some 40 shrines and platforms (of different types) were built between the cairns and on the field perimeter (Galili 2019). Cairns continued to be used through the Terminal Timnian and it is possible that existing open-air shrines continued to serve those populations. Rothenberg and Glass (1992) see these burial fields as an indication of continuity of the indigenous population throughout the entire Timnian sequence.

Although Haiman (1993) dated the cairn fields at Nahal Mitnan and other sites in the Negev Highlands to the Late Timnian (Early Bronze Age II), Saidel (2017) has disputed the dates, suggesting a much earlier date of construction. He notes that the stone fill of the cairns was partially dismantled and served as building material for other, later structures. Certainly, in the well-dated cairns at Ramat Saharonim and in Jordan, there were no Early and Middle Timnian occupation sites adjacent to cairns. Similar patterns of dismantling of cairns and reuse of the building materials for the construction of other, later funerary structures was also noted at Har Tzuriaz. The greater diversity and number of grave goods within cairns excavated and published by Haiman (1993) may be related to re-use (or a later phase of use) in the Middle or Late Timnian (Saidel 2017). Reuse of cairns has been identified at Ramat Saharonim (Rosen et al. 2007) and the recently excavated cairn field of Tamar I in the eastern Negev (Galili, personal observation). The reuse of stones from cairns to construct habitation sites or other monuments points to a certain detachment from ancestral traditions.

Standing stones/stelae are often included in the discussion of ritual in the Negev desert. Hundreds of stones found in constellations ranging from a single stone to over a dozen have been documented throughout the Negev. These are dated by to 11,000–2000 BCE, with most attributed to the sixth to third millennium BCE (Avner 2018, 26–31). These dates derive from radiocarbon dating of charcoal, whose contexts and association with the stelae are unclear, and may or may not reflect activities related to the standing stones. The standing stone phenomenon is spatially widespread and difficult to define. Stelae found within clear archaeological contexts, such as the sanctuaries at Tell Arad, Hatzor, and Kitan, date from the Early through Late Bronze Ages (Bloch-Smith 2015, 100). Although some of the stelae seem to be integrated into cairns and even the shrines, the independent standing stones of the Negev are almost impossible to date, and even harder to interpret; it is at present difficult to integrate them into the larger picture.

The above review presents the development and evolution of ritual structures and space throughout the Early-Middle/Late Timnian. It is unclear to what extent these sacred precincts continued to exist and serve as an integral core of communal traditions in the Late/Terminal Timnian; we may assume that over certain periods of time different practices co-existed. As the square-shaped structures were added after the rectangular shrines, we may assume that for some time the two co-existed. Few finds were found in excavations of the open-air sanctuaries, but unlike material culture assemblages from habitation sites, the absence of occupation debris does not reflect the extent of use of the open-air sanctuaries, but rather the ritual function of these structures, contrasting with the domestic. The physical presence of people and the use of the sanctuaries is seen in the destruction of the uppermost layer of the original surface. At Ramat Saharomin, for example, the original pre-construction surface showed a stable hammada with a layer of carbonate nodules immediately beneath the surface. In the immediate vicinity of the site, the surface was disturbed, with no hammada and only an unstructured carbonate nodule subsurface, reflecting human presence and trampling at the site (Porat et al. 2006). Continuous use of the site would amplify this pattern, but is not evident, suggesting there was no intensive use by large groups of people.

Ritual plays a crucial role in establishing and maintaining many aspects of the social order, stabilizing and reinforcing social configurations. Ritual behavior may indicate the affirmation of institutional facts significant to society (Renfrew 2007). The spatial continuities preserved in coincidence of the structures maintained a spatial sanctity, but by the Terminal Timnian, changes in the structures suggest changes in the forms and meaning of the rituals.

The continued use of cairns is testified through the Middle/Late Timnian (e.g., Saidel 2017) with evidence of re-use as late as the Hellenistic (Porat et al. 2006) and later periods. Without the construction of new cairns in the later phases of the Timnian, the adjacent installations, elongated walls, and platforms likely went out of use.

Reconstructing the forms of ritual in the later phases of the Timnian culture is difficult. In terms of mortuary cult, there is good stratigraphic evidence for the continued use of the cists within the cairns, at least through the mid-third millennium BCE, and perhaps through the end of the period. The evolution of the shrine systems, as described above, suggests a very long period of use, and given other cultural continuities (material culture, architecture, symbolism as reflected in the rock art), we posit general ritual continuities through the Late Timnian and extending into the Terminal Timnian, at least among segments of the population.

Although the orant figures penetrated desert traditions in the rock art, other northern influences, such as geometric patterns, snake and lion motifs (Ben-Tor 1991), or complex hunt and dance scenes, are rarely reflected in Negev rock art of the period. The male ibex motif is pan-Near Eastern and serves as a signifier of any number of connotations and meanings. Therefore, at present we suggest that the later phases of the Timnian preserved general continuities with the earlier, with the adoption of limited memes from the settled zone.

From Archaeology to Society

The open-air shrines in their different forms, the tumuli, the geoglyphs, and the petroglyphs, are all aspects of the Timnian culture and symbol systems. The Timnian culture itself, especially in its early phases, reflects the major social and cultural changes concomitant with the adoption of domestic herd animals into a hunter-gatherer society and its evolution to a tribal society. In particular, we can see changes in architecture, in the development of the pen-and-attached-room complexes, the development of communal hunting in desert kites, and increasing diversity of exchange systems. These all attach to a fundamentally new social matrix showing greater social hierarchy, increasing territorial behavior, and changes in social structure and linkages, inevitably accompanied by new belief systems and their physical manifestations which serve as the social adhesives for these new social formulations. Rosen (2015, 2017) has suggested that they represent the rise of tribal societies in the Near Eastern deserts.

Early Timnian open-air shrines and cairns likewise demanded a basic architectural concept, and a work force to construct them. The total weight of the double, western wall at Ramat Saharonim is estimated minimally at 30 tons (Rosen et al. 2007). Based on the geometry and mass of the wall, and on experimental work (Galili, personal communication), we estimate some 60 to 90 workdays for locating, transporting, and building each rectangular shrine. The construction of a cairn could take 30 to 60 workdays to complete. A group of 60 builders (that is, only the people directly involved in construction) could complete the construction of a cairn in a day, but a group consisting of 15 builders would require four days.

The workforce and organization needed for construction of the monuments contrasts with the simple nature of the habitation sites. Most sites do not exceed 10 rooms, and many only consist of three or five, housing far fewer people than presumably would be required to build the monuments. Thus, the shrines and cairn fields probably reflect aggregation sites, both in terms of construction and use. They form a type of architectural canon maintained by ritual activities (see Assmann 1995). The summer solstice alignment suggests specifically aggregation at the spring-summer transition (Rosen 2015). The very activity of working together, the reality of completing the work, and the subsequent experience of using it communally for ceremonies and/or mortuary practices, in effect produce and reproduce new social units (Renfrew 2007). The monuments formed and built by communally shared labor maintained tribal identity and reinforced social and regional ties while forming and reinforcing an underlying coherent culture (Abu-Azizeh 2013; Rosen 2011; Rosen et al. 2007). Analyses of the typology and spatial patterning suggests that some cairns and shrines were also imbued with social codes and served as identity symbols (Galili 2019).

The shrines, their location near the cairns, and the cairn fields indicate communal use. The absence of skeletal remains in many of the cairns, together with evidence of repeated burials and the re-arrangement of bones (Rosen et al. 2007), indicate a series of funerary-related activities and rituals. The sequence of annual (?) rituals may have involved the removal of the skeleton, leaving the cairn empty until the next burial. Abu-Azizeh et al. (2014) suggest that the rectangular and trapezoidal platforms of the Al-Thulaythuwat cairn fields “might have been used for temporary deposition of the bodies during the de-fleshing of the skeleton, before the transfer of the bones to the final tomb, possibly during a subsequent visit of the group to the site. Such an interpretation does not necessarily exclude a parallel role for the rectangular platforms in mortuary banquets or feasting” (Abu-Azizeh et al. 2014, 175). The cairns and platforms (perhaps functioning shrines in a different format), the construction of long walls and open-air shrines, and the direction of the cist in cairns all sharing a west-northwestern orientation (290°–305°)2, the direction of the setting sun, and specifically the summer solstice sunset (S. A. Rosen and Rosen 2003), connect between cosmology, death, and mortuary ritual. These connections, seen first in the Early Timnian open-air shrines, were maintained in the desert for at least two millennia, as seen in the orientation of the Late Timnian nawamis (Bar-Yosef et al. 1983), and probably through the third millennium BCE.

The archaeology of Timnian social structure is ambiguous. On the one hand, monumental architecture (cairns, open-air shrines), demanding communal effort and labor organization, suggests hierarchy, while on the other, no differences in status are evident in the architecture of habitation sites or, for that matter, in the contents or structure of the shrines and cairn fields themselves. This contradiction may reflect tensions within an evolving society. The few grave goods and the fact that the cairns are roughly similar in size with little ‘stylistic’ variability suggests little social stratification. The statistically random placement of the cairns argues against well-developed hierarchies in the location of burials.3 At this stage, without further data on the actual individuals interred within the cairns, their age and gender, it is difficult to assess to what degree the society was egalitarian. The cairn fields perhaps may reflect a specific class of society, although the large number of cairns and fields (reaching thousands of tombs with multiple interments) would suggest that a large proportion of the population is represented. On the other hand, the construction of such monuments themselves indicates the need for hierarchical organization of labor. These apparent tensions between egalitarian tendencies and organizational needs fit a tribal level of social organization (Rosen 2015).

Levels of ritual performance are conducted at three levels, the household level, the settlement level, and the larger community level (Watkins 2015). We have no direct evidence of household ritual within the Timnian culture, but it seems likely that burials were conducted at the second level, in which the people of a settlement constructed the cairn and participated in the mortuary rites. It would be difficult to contact and gather distant groups at short notice. The larger group, the tribe, including people from a number of communities in the region, would congregate at set times at a central place. The act of constructing the central place memorializes a collective memory and community identity which later was maintained by ritual practices (Watkins 2015). The central place was distanced from the everyday, and rites were conducted by institutional communication and figures of memory. The collective memory forms the cultural identity, which then serves to connect people who may not personally know each other and helps determine who we are versus them (Assmann 1995; Watkins 2015).

Fujii (2013) suggests that the open-air sanctuaries represented pseudo-houses, with an outline of a courtyard/pen such as those adjacent to the structures of the period, in spite the fact that the open-air sanctuaries are rectangular or square in shape and the Timnian habitations were of an irregular round shape. He claims that the courtyard-pen is the essence of the Timnian house and culture, representing the herd and its place in the courtyard-pen as well as within society. Following this concept, placing the geoglyph predators outside of the courtyard, as those at Uvda 6, symbolically places the predators in a liminal space outside of the society. In this way, the leopards symbolized life-threating animals, predators who attacked the herd and put the society into danger, per contra Avner (2002, 14), who suggests they symbolize deities and fertility. If so, the horned animal depicted in the Uvda 6 shrine may represent an offering not to the gods, as Avner (Avner 2002, 114) and Yogev (1983) suggest, but rather to the predators, to prevent them from attacking the herd and community. It is roughly at this time that stone features, identified as leopard traps, were constructed across the Southern Levant deserts (Avner 2002, 18; Hadas 2011; Porat et al. 2013). This may be connected to in-group/out-group definitions, in which case the leopards would represent the foreign, rather than ‘those who belong’ (see Assmann 1995). However, it must be stressed that these reconstructions are speculative. We have little means of confirming them, and the futility of such speculations toward emic interpretations should be clear.

The integration of the herd into the household brought on responsibilities of maintenance that translated into the need to secure pasture and water sources. As the number of pastoral settlements grew, the demand for resources increased, territoriality increased, and markers were needed. The repetitive visits to the cairn field, whether for construction, burial, reuse for burial, or related visits and rituals, indicate that they played an active role in ritual life. These cemeteries marked territory and validated ancestral claims connecting the people to the land (Rowley-Conwy 2001, 44). To further develop this idea, cemeteries functioned as symbols of corporate rights to resources that are not distributed equally, either in space or between groups (Saxe 1970). Cemeteries may be in the center or perimeter of the territory. Abu-Azizeh et al. (2014) suggest that the cairn fields and associated monuments represented focal points for the mobile populations through which they organized and structured the landscape in the context of their newly established pastoral nomadic way of life.

Our understanding of the Late and Terminal Timnian cult is limited. Even given evidence for continuity with earlier phases, we detect the ebbing of the seasonal communal gatherings centred around mortuary and ancestry in the Middle-Late Timnian. At roughly the same time the number of petroglyphs slowly increase with numerous images of ibex and (relatively few) orant. Both open-air sanctuaries and rock art serve as a form of expression and adaptation through which to resolve and communicate different aspects of cultural change.

Returning to Renfrew’s (1985) four markers identifying ritual as sacred, the Timnian ritual precincts exhibit:

-

Attention focusing. There seem to be two possible focal points in the Timnian precincts: the first is the western wall of the open-air sanctuaries, the second the cairn fields set above along the surrounding ridges and peaks. In the case of interment, the cairns serve as the focal point, though their settings and contexts were also imbued with meaning.

-

Special aspects of the liminal zone. Burial cairns are in or form a liminal zone almost by definition. People congregate at a cairn either to inter or to commemorate the deceased. Galili (2019) has suggested that the setting of these is related to territorial land use, overlooking large drainage basins, the ‘territory’. The cairns are constructions within the liminal zone.

-

Presence of the transcendent and its symbolic focus. The cairn’ silhouettes on the skyline and the rectangular/square and rectangular shaped open-air sanctuaries are unquestionably symbolic. The shrine alignments with the setting sun of the summer solstice clearly have cosmological implications (Rosen 2015), although further interpretation is merely speculative (Marcus 2007).

-

Participation and offering. Participations starts with the construction of a monument, formed and built by communally shared labor (Renfrew 2007). With the setting of the open-air shrines on large plains and their construction style, there is a sense of exposure and openness. Every act carried out within a shrine would be in plain view. The scarcity of material culture suggests an important role for immaterial ritual, perhaps things spoken (Kyriakidis 2007a).

Concluding Remarks

Summarizing these ideas, and trying to synthesize the rituals identified into basic ideas on Timnian beliefs, we suggest the following:

-

Timnian cosmology seems to have emphasized death. The coincidence of the shrines with the cairn fields, mortuary systems with the summer solstice (the season of death in the Near East), suggests a focus on death. The seasonal structure of shrines, oriented toward the solstice, and the very need to construct shrines and cairns suggests seasonal aggregation, perhaps feasting. The geoglyphs of predators can also be interpreted in light of death rituals. The choice of stones, rounded white limestone cobbles versus the dark, jagged-edged patina covered boulders, and their integration within the open-air shrines, cairns, and installations, was intentional and laden with culturally embedded symbolism. Given the shrines, the cairn fields, and the geoglyphs, we trace an incipient monumental cosmology projecting the evolving structures of Timnian society and undoubtedly much richer than we can begin to understand.

-

The repeated use of the cairns, and the rearrangement of bones, suggest family ties in the mortuary ritual. The random spatial distribution of the cairns within the fields and the few burial goods suggest little social stratification. Even in later manifestations of Timnian burial systems, as in the Sinai nawamis, it is difficult to see social differentiation.

-

Petroglyphs were not associated with the open-air shrines or cairns. None of the stones of the open-air shrines or standing stones/stelae were engraved. Petroglyphs are also slightly later in date than the initial construction phase of the sacred precincts. Though the rock art does not mirror everyday mundane activities and life, it is not directly connected to the ritual realm, either. Analysis of Negev rock art suggests corporate identities, perhaps even unconscious communications, based on tribal identity and presence. Through the rock art motifs, we can also recognize foreign people, ideas, and ideologies, some of which were integrated into Negev Timnian culture.

-

The rise of public, monument-based ritual, in contrast to preceding Pre-Pottery Neolithic societies of the desert, suggests more prominent roles for ritual leadership. The great difference between the relatively simple camp and dwelling sites and the magnitude of the burial and ritual sites reflects the importance of this mortuary heritage. The tension between the essentially egalitarian ideologies seen in the cairn fields and the need for levels of social organization expressed in their construction, and in the shrines, is integral to the dynamics of Timnian society.

-

The similarity noted between open-air shrines, cairns, and later nawamis in the attention and details related to orientation over large geographic regions suggest an overall Timnian culture, or perhaps the Timnian as a local manifestation of a larger, general desert-pastoral culture. The apparently chronological developments noted for the Negev open-air shrines reflect continuity. Comparing to the material from Southern Jordan, Northern Arabia, and Sinai, regionalization can also be traced. The spatial patterns of open-air shrines and cairns within the landscape formed part of the symbolic cultural codes of the nomadic cultures throughout the Timnian. The cairn fields constitute expressions of group identity, maintained by cult and ritual.

-

The relationship between the courtyard and the more massive western wall, the setting of most of the open-air shrines and platforms east of cairns, may reflect the cosmology of the people. The cairn fields had three integrated functions: burial and ritual, territorial markers, and the reinforcement of social identity.

Three fundamental pitfalls impact our understanding of early belief systems. First, the tendency to project modern beliefs backwards to ancient times, to trace modern systems to some source cosmology, automatically biases our perspectives on ancient beliefs. Without the complete chronological sequence of beliefs and belief structures, it is not possible to establish whether a particular system, symbol, rite, or practice is in some sense ancestral to later practices. Belief and symbol systems are far too dynamic to trace simple linear paths from period A to period X.

Second, there is always a danger in relying too much on ethnography to supply models for the ancient past. Modern nomadic cultures are not living fossils of ancient ones; for example, recent Bedouin practices and beliefs have evolved no less than their village and urban cousins. There are no fossilized peoples. Analogies must be processual, not direct, and must consider both context and long-term trends.

Finally, belief systems must, by their nature, be integrated into their associated social systems. Small scale heterarchical systems will not have centralized hierarchical cosmologies or religious structures, and centralized hierarchical societies must have similarly organized religious structures. These systems must function within their respective societies, and without agreement between the basic structures they cannot do so.

In Christopher Hawke’s (1954) famous ladder of archaeological inference, he claimed that religion and belief systems were the most difficult aspects of ancient societies to reconstruct. He based this conclusion on the assumption that the specifics of mythologies and cosmologies were the primary goals of archaeological investigations of religion. However, archaeology offers data, as in the example presented here, which, if stripped of the desire to arrive at mere mythology, can offer crucial insights into the fundamental principles, trends, and the actual structures of religion and belief.

References

Abadi, Yael, and Steven A. Rosen. 2008. “A Chip Off the Old Millstone.” In New Approaches to Old Stones: Recent Studies of Groundstone Artifacts, edited by Rowan Yorke and Jennie R. Ebeling, 99–115. London: Equinox Publishing Ltd.

Abe, Masashi. 2008. “The Development of Urbanism and Pastoral Nomads in the Southern Levant – Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age Stone Tool Production Industries and Flint Mines in the Jafr Basin, Southern Jordan.” PhD diss., University of Liverpool.

Abu-Azizeh, Wael. 2013. “The South-Eastern Jordan’s Chalcolithic – Early Bronze Age Pastoral Nomadic Complex: Patterns of Mobility and Interaction.” Paléorient 39 (1): 149–76.

Abu-Azizeh, Wael, Mohammad B. Tarawaneh, Fawzi Abudanah, Saad Twaissi, and Abeed Al-Salameen. 2014. “Variability Within Consistency: Cairns and Funerary Practices of the Late Neolithic/Early Chalcolithic in the Al-Thulythuwat Area, Southern Jordan.” Levant. Journal of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History 46 (2): 161–85.

Amiran, Ruth. 1972. “A Cult Stele from Arad.” Israel Exploration Journal 22: 86–88.

Amiran, Ruth, Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, and Jonathan Glass. 1973. “The Interrelationship Between Arad and Sites in the Southern Sinai in the Early Bronze II.” Israel Exploration Journal 23: 33–38.

Amiran, Ruth, Ornit Ilan, and Michael Sebbane. 1997. Canaanite Arad: Gateway City to the Wilderness. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

Assmann, Jan. 1995. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” Translated by John Czaplicka). German Critique Spring 65: 125–33.

Avner, Uzi. 2002. “Studies in the Material and Spiritual Culture of the Negev and Sinai Populations During the 6th-3rd Millennia B.C.” PhD diss., Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

———. 2018. “Protohistoric Developments of Religion and Cult in the Negev Desert.” Tel Aviv 45: 23–62.

Bar-Adon, Pesach1962. 1962. “Another Ivory Bull‘s Head from Palestine.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental 349 Research 165: 46–47.

Bar-Oz, Guy, Melinda Zerderb, and Frank Holec. 2011. “Role of Mass-Kill Hunting Strategies in the Extirpation of Persian Gazelle (Gazella Subgutturosa) in the Northern Levant.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (18): 7345–50.

Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Anna Belfer, Avner Goren, and Patrichia Smith. 1977. “The Nawamis Near Ein Huderah (Eastern Sinai).” Israel Exploration Journal 27: 65–88.

Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Anna Belfer-Cohen, Avner Goren, Israel Herskovitz, Henk Mienis, Benjamin Sass, and Ornit Ilan. 1986. “Nawamis and Habitation Sites Near Gebel Gunna, Southern Sinai.” Israel Exploration Journal 36: 121–67.

Bar-Yosef, Ofer, Israel Hershkovitz, Gideon Arbel, and Avner Goren. 1983. “Orientation of Nawamis Entrances in Southern Sinai: Expressions of Religious Belief or Seasonality?” Tel Aviv 10: 52–60.

Beck, Perahia. 1995. “Sugyot Beomanout Shel Ertetz Israel Batekefht Haberonza Hakeduma [Issues in the History of Early Bronze Age Art in Eretz Israel].” Cathedra 76: 3–33.

Beit-Arieh, Itzhaq. 1986. “Two Cultures in South Sinai in the Third Millennium B.C.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 263: 27–54.

———. 2003. Archaeology of Sinai the Ophir Expedition. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

Beit-Arieh, Itzhaq, and Ram Gophna. 1981. “The Early Bronze Age II Settlement at ‘Ain El-Qudeirât (1980-1981).” Tel Aviv 8: 128–35.

Ben-Tor, Amnon. 1977. “Cult Scene on Early Bronze Age Cylinder Seal Impressions from Palestine.” Levant. Journal of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History 9: 90–100.

———. 1985. “Glyptic Art of the Early Bronze Age Palestine and Its Foreign Relations.” In The Land of Israel: Cross-Roads of Civilizations, edited by E. Lipiński, 1–25. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters.

———. 1991. “New Light on Cultic Cylinder Seal Impressions from the Early Bronze Age in Eretz Israel.” Eretz-Israel. Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies 23: 28–44.

Betts, Alison, and Helms Svend. 1986. “Rock Art in Eastern Jordan: ‘Kite’ Carvings?” Paléorient 12 (1): 67–72.

Bloch-Smith, Elizabeth. 2015. “Massebot Standing for Yhwh the Fall of a Yhwistic Cult Symbol.” In Worship, Women, and War Essays in Honor of Susan Niditch, edited by John J. Collins, Tracy M. Lemos, and Saul M. Olyan, 99–116. Rhode Island: Brown Judaic Studies Providence.

Callaway, Joseph A. 1974. “A Second Bull‘s Head from Ai.” Bulletin of the American School of Research 213: 57–61.

Cauwe, Nicolas, Serge Lemaitre, Vincianne Picalause, Paul-Louis Van-Berg, and Marc Vander Linden. 2004. “Desert-Kites of the Hemma Plateau (Hassake, Syria).” Paléorient 30 (1): 89–99.

Cleveland, L. Ray. 1961. “An Ivory Head from Ancient Jericho.” Bulletin of the American School of Research 163: 30–36.

Cohen, Rudolph. 1992. “The Nomadic or Semi-Nomadic Middle Bronze Age I Settlements in the Central Negev.” In Pastoralism in the Levant: Archaeological Materials in Anthropological Perspectives. Monographs in World Archaeology No. 10, edited by Ofer Bar-Yosef and Antoly Khazanov, 105–31. Wisconsin: Prehistory Press.

———. 1999. Hahityashvut Hakeduma Behar Hanegev [Ancient Settlement of the Central Negev]. IAA Reports 6. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

Cohen, Rudolph, and William G. Dever. 1979. “Preliminary Report of the Second Season of the ‘Central Negev Highlands Project’.” Bulletin of American Schools of Oriental Research 236: 41–60.

Dunseth, Zach, Israel Finkelstein, and Ruth Shahack-Gross. 2018. “Intermediate Bronze Age Subsistence Practices in the Negev Highlands, Israel: Macro- and Microarchaeological Results from the Sites of Ein Ziq and Nahal Boqer 66.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 19: 712–26.

Eddy, Frank W., and Fred Wendorf. 1999. An Archaeological Investigation of the Central Sinai, Egypt. Cairo: The American Research Center in Egypt, Inc. and The University Press of Colorado.

Eisenberg-Degen, Davida. 2010. “A Hunting Scene from the Negev: The Depiction of a Desert Kite and Throwing Weapon.” Israel Exploration Journal 60 (2): 146–65.

Eisenberg-Degen, Davida, and George Nash. 2014. “Hunting and Gender as Reflected in the Negev Rock Art.” Time and Mind 7: 259–77.

Eisenberg-Degen, Davida, and Steven A. Rosen. 2013. “Chronological Trends in Negev Rock Art: The Har Michia Petroglyphs as a Test Case.” Arts 2: 225–52.

Finkelstein, Israel. 1990. “Early Arad — Urbanism of the Nomads.” Zeitschrift Des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 106: 34–50.

Fujii, Sumio. 2013. “Chronology of the Jafr Prehistory and Protohistory: A Key to the Process of Pastoral Nomadization in the Southern Levant.” Syria. Revue d’art Oriental et d’archéologie 90: 49–125.

———. 2016. “Slab-Lines Feline Representations: New Findings at ‘Awja 1, a Late Neolithic Open-Air Sanctuary in Southenmost Jordan.” In Proceedings of the 9th ICAANE, Basel 2014 Conference, 3:549–59.

Galili, Roy. 2019. “Landscape Archaeology, and Social Distribution as a Key to the Lack of Burials and to Understanding the Role of the Cairn Sites.” In Worship and Burial in the Shfela and the Negev Regions Throughout the Ages, edited by Daniel Varga, Yael Abadi-Reiss, Gunnar Lehmann, and Daniel Vainstub, 79–98. Beer-Sheva: Ben Gurion University of the Negev and Israel Antiquities Authority.

Garfinkel, Yosef. 2003. Dancing at the Dawn of Agriculture. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Garstang, John. 1967. “Jericho: City and Necropolis.” Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology 19: 3–22.

Getzov, Nimrod. 2006. The Tel Bet Yerah Excavations 1994-1995. IAA Reports 28. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

Gopher, Avi, and A. Nigel Goring-Morris. 1998. “Abu Salem: A Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Camp in the Central Negev Highlands.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 312: 1–20.

Goring-Morris, A. Nigel. 1993. “From Foraging to Herding in the Negev and Sinai: The Early to Late Neolithic Transition.” Paleorient 19 (1): 65–89.

Goring-Morris, A. Nigel, Avi Gopher, and Steven A. Rosen. 1994. “The Neolithic Tuwailan Cortical Knife Industry of the Negev Proceedings of the First Workshop on PPN Chipped Lithic Industries.” In Neolithic Chipped Stone Industries of the Fertile Crescent, edited by Hans George K. Gebel and Stefan K. Kozlowski, translated by Stefan K. Kozlowski, 511–24. Berlin: Ex Orient.

Hadas, Gideon. 2011. “Hunting Traps Around the Oasis of ʿEn Gedi.” Israel Exploration Journal 61 (1): 2–11.

Haiman, Mordechai. 1992. “Cairn Burials and Cairn Fields in the Negev.” Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research 287: 25–45.

———. 1993. “An Early Bronze Age Cairn Field at Nahal Mitnan.” ʽAtiqot 12: 49–61.

———. 1996. “Early Bronze Age IV Settlement Pattern of the Negev and Sinai Deserts: View from Small Marginal Temporary Sites.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 303: 1–32.

Hawkes, Christopher. 1954. “Archaeological Theory and Method: Some Suggestions from the Old World.” American Anthropologist 56 (2): 155–68.

Helms, Svend, and Alison Betts. 1987. “The Desert ―Kites of Badiyat Esh-Sham and North Arabia.” Paléorient 13 (1): 41–67.

Hershkovitz, Israel, Yair Ben-David, Baruch Arensburg, Avner Goren, and Avi Pichasov. 1987. “Rock Engravings in Southern Sinai.” In Sinai, edited by Gdalyahu Gvirtzman, 1: 605–16. 1.

Horwitz, Liora K. 2014. “Early Bronze Age Fauna from Three Sites in the Negev Highlands.” In Excavations in the Western Negev Highlands Results of the Negev Emergency Survey 1978-89, edited by Benjamin Saidel and Mordechai Haiman, 191–205. British Archaeological Reports International 2684. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Hultkrantz, Äke. 1966. “An Ecological Approach to Religion.” Ethnos 31: 131–50.

Israel, Yigal, and Dov Nahlieli. 1998. “Sreedai Henyonim Veminhagai Pulhan Bedarchai Hamedbar [Campsite Ritual Activity along the Desert Roads].” In Mechkarim Bearkiologia shel Navadim BaNegev VeSinai [Studies in the Archaeology of Nomads in the Negev and Sinai], edited by Shmuel Ahituv, 145–54. Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik.

Knabb, K. A., S. A. Rosen, S. Hermon, J. Vardi, and L. K. Horwitz. 2018. “A Middle Timnian Nomadic Encampment on the Faynan-Beersheva Road: Excavations and Survey at Nahal Tsafit (Late 5th/Early 4th Millennium BCE).” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 380: 27–60.

Kozloff, Bennett. 1981. “Pastoral Nomadism in the Sinai: An Ethno-Archaeological Study.” Production Pastorale St Societe: Bulletin d‟Ecologie Ed d‟Anthropologie 8: 19–24.

Kyriakidis, Evangelos. 2007a. “Archaeologies of Ritual.” In Archaeology of Ritual, edited by Evangelos Kyriakidis, 289–308. Costen Advanced Seminars 3. Los Angeles: Costen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

———. 2007b. “In Search of Ritual.” In Archaeology of Ritual, edited by Evangelos Kyriakidis, 1–8. Costen Advanced Seminars 3. Los Angeles.: Costen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

Landau, Serge Y., Levana Dvash, Philipa Ryan, David Saltz, Tova Deutch, and Steven A. Rosen. 2020. “Faecal Pellets, Rock Shelters, and Seasonality: The Chemistry of Stabling in the Negev of Israel in Late Prehistory.” Journal of Arid Environments 181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2020.104219.

Manclossi, Francesca, Steven A. Rosen, and Pierre de Miroschedji. 2016. “The Canaanean Blades from Tel Yarmuth: A Technological Analysis.” Paléorient 42: 53–79.

Marcus, Joyce. 2007. “Rethinking Ritual.” In Archaeology of Ritual, edited by Evagelos Kyriakidis, 43–50. Costen Advanced Seminars 3. Los Angeles: Costen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

Maringer, Johannes. 1979. “Adorants in Prehistoric Art: Prehistoric Attitudes and Gestures of Prayer.” Numen-International Review for the History of Religions 26 (2): 215–30.

Milevski, Ianir. 2013. “The Exchange of Flint Tools in the Southern Levant During the Early Bronze Age.” Lithic Technology 38 (2): 202–19.

Miller, James J. 1999. “Excavations at Sinai-18. The Khasem El Taref Site, Zarnoq Locality.” In An Archaeological Investigation of the Central Sinai, Egypt, edited by F. W. Eddy and F. Wendorf, 181–92. Boulder: The American Research Center in Egypt and the University of Colorado.

Phillips, James L., and Bruce G. Gladfelter. 1989. “A Survey in the Upper Wadi Feiran Basin, Southern Sinai.” Paléorient 15: 113–22.

Porat, Naomi. 1989. “Petrography of Pottery from Southern Israel and Sinai.” In L’urbanisation de La Palestine à L’âge Du Bronze Ancient, edited by Pierre de Miroschedji and Pierre Page, 169–88. British Archaeological Reports International Series 527. Oxford.

Porat, Naomi, Uzi Avner, Assaf Holzer, Rahamim Shemtov, and Liora K. Horwitz. 2013. “Fourth-Millennium-BC ‘Leopard Traps’ from the Negev Desert (Israel).” Antiquity 87 (337): 714–27.

Porat, Naomi, Steven A. Rosen, Elisabetta Boaretta, and Yoav Avni. 2006. “Dating the Ramat Saharonim Late Neolithic Desert Cult Site.” Journal of Archaeological Science 33: 1341–55.

Renfrew, Colin. 1985. The Archaeology of Cult: The Sanctuary at Phylakopi. London: Thames and Hudson.

———. 2007. “The Archaeology of Ritual, of Cult, and of Religion.” In Archaeology of Ritual, edited by E. Kyriakidis, 109–21. Costen Advanced Seminars 3. Los Angeles: Costen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

Rosen, Steven A. 1988. “Notes on the Origins of Pastoral Nomadism: A Case Study from the Negev and Sinai.” Current Anthropology 29: 498–506.

———. 1997. Lithics After the Stone Age: A Handbook of Stone Tools from the Levant. Walnut Creek: AltaMira.

———. 2003. “Early Multi-Resource Nomadism: Excavations at the Camel Site in the Central Negev.” Antiquity 77 (298): 749–60.

———. 2011. “Desert Chronologies and Periodization Systems.” In Culture, Chronology and the Chalcolithic: Theory and Transition, edited by L. Lovell Jaimie and M. Rowan Yorke, 69–81. London: Council for British Research in the Levant.

———. 2013. “Evolution in the Desert: Scale and Discontinuity in the Central Negev (Israel) in the Fourth Millennium BCE.” Paléorient 39 (1): 139–48.

———. 2015. “Cult and the Rise of Desert Pastoralism: A Case Study from the Negev.” In Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East, edited by N. Laneri and Oxbow, 38–47. Oxford: Oxbow.

———. 2017. Revolutions in the Desert. The Rise of Mobile Pastoralism in the Southern Levant. Routledge.

Rosen, Steven A., Fanny Bocqentin, Yoav Avni, and Naomi Porat. 2007. “Investigations at Ramat Saharonim A Desert Precinct in the Central Negev.” Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research 346: 1–27.

Rosen, Steven A., and Yaniv J. Rosen. 2003. “The Shrine of the Setting Sun: Survey of the Sacred Precinct at Ramat Saharonim.” Israel Exploration Journal 53 (1): 1–19.

Rosen, Steven A., Arkady B. Savinetsky, Yosef Plakht, Nina K. Kisseleva, Bulat F. Khassanov, Andrey M. Pereladov, and Mordechai Haiman. 2005. “Dung in the Desert: Preliminary Results of the Negev Holocene Ecology Project.” Current Anthropology 46: 317–27.

Ross, June, and Iain Davidson. 2006. “Rock Art and Ritual: An Archaeological Analysis of Rock Art in Arid Central Australia.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 13 (4): 305–41.

Rothenberg, Beno, and Jonathan Glass. 1992. “The Beginnings and the Development of Early Metallurgy and the Settlement and Chronology of the Western Arabah, from the Chalcolithic Period to Early Bronze IV.” Levant. Journal of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History 24: 141–57.

Roux, Valentine, and Caroline Jeffra. 2015. “The Spreading of the Potter’s Wheel in the Ancient Mediterranean. A Social Context-Dependent Phenomenon.” In The Transmission of Technical Knowledge in the Production of Ancient Mediterranean Pottery Proceedings of the International Conference at the Austrian Archaeological Institute at Athens 23rd– 25th November 2012, edited by Walter Gauss, Gudren Klebinder-Gauss, and Constance von Rüden. Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut Sonderschriften Band 54.

Rowley-Conwy, Peter. 2001. “Time, Change and the Archaeology of Hunter Gatherers.” In Hunter Gatheres an Interdisciplinary Perspective, edited by Catherine Panther-Brick, Robert H. Layton, and Peter Rowley-Conwy, 39–72. Durham: University of Durham.

Saidel, Benjamin A. 2002. “The Excavations at Rekhes Nafha 396 in the Negev Highlands, Israel.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 325: 37–63.

———. 2011. “Talking Trash: Observations on the Abandonment of Broadroom Structures in Southern Sinai During the Early Bronze Age II.” In Daily Life, Materiality, and Complexity in Early Urban Communities of the Southern Levant Papers in Honor of Walter E. Rast and R. Thomas Schaub, edited by Meredith S. Chesson, 173–84. Pennsylvania: Eisenbrauns.

———. 2017. “An Alternative Date for the Nahal Mitnan Cairn Field in the Western Negev Highlands: Identifying an Early Timnian Tumuli Tradition in the Southern Levant.” Paléorient 43 (1): 125–40.

Schwimer, Lior, and Yuval Yekutieli. 2017. “Visitors from the Intermediate Bronze Age? Cresent Headed Figures in Negev Rock Art.” The Ancient Near East Today V (12): Chapter 2.

———. 2021. “Intermediate Bronze Age Crescent Headed Figures in the Negev Highlands.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. https://doi.org/10.1086/712920.

Sognnes, Kalle. 1994. “Ritual Landscapes. Toward a Reinterpretation of Stone Age Rock Art in Trøndelag, Norway.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 27 (1): 29–50.

Sussman, Varda. 1980. “A Relief of a Bull from the Early Bronze Age.” Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research 237: 75–77.

Tchernov, Eitan, and Ofer Bar-Yosef. 1982. “Animal Exploitation in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Period at Wadi Tbeik, Southern Sinai.” Paléorient 8 (2): 17–37.

Watkins, Trevor. 2015. “Religion as Practice in Neolithic Societies.” In Defining the Sacred Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East, edited by N. Laneri, 153–60. Oxford & Philadelphia: Oxbow Books.

Whitley, David. 2005. Introduction to Rock Art Research. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Yakar, Jak. 1989. “The so-Called Anatolian Elements in the Late Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age Cultures of Palestine: A Question of Ethnocultural Origins.” In L’urbanoisation de La Palestine à L’âge Du Bronze Ancient Part II, edited by Pierre de Miroschedji, 341–54. BAR International Series, 527 (ii).

Yekutieli, Yuval. 2002. “Divine Royal Power.” In In Quest of Ancient Settlements and Landscapes, edited by Edwin C. M. van der Brink and Eli Yannai, 243–53. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University.

Yogev, Ora. 1983. “In Quest of Ancient Settlements and Landscapes [A Fifth Millennium BCE Sanctuary in the Uvda Valley].” Qadmoniot 4 (64): 118–22.

We here adopt the term shrine to indicate the relatively small, open-air ritual structures common in the Negev and surrounding regions. Other terms, for example, ‘temple,’ have connotations which are inappropriate for the rituals of small-scale societies. Shrine is intended as a neutral term, without additional connotations.↩︎

The western orientation is determined by the fact that the courtyard is east of the emphasized wall. We interpret the emphasized wall as the focal point of the shrine. The congregated people would likely be in (or possibly around?) the courtyard facing the emphasized wall, i.e., westward. The geography of the Ramat Saharonim shrines, oriented between two low hills and toward a black, extinct volcano, with the summer solstice sun setting over the north wall of the Makhtesh Ramon, clinches the case for the summer solstice orientation, per contra Avner (2018).↩︎

An as yet unpublished nearest neighbor analyses of the Tamar 1 indicates random placement of cairns relative to one another.↩︎