Jain Life Reimagined: An Examination of Jain Practice and Discourse during the Covid-19 Pandemic

This article analyzes the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the religious practices and the public discourse of Jains in the U.S.A. and India. On the institutional level, I show how Jain organizations made extensive efforts to connect digitally with their community members when collective, in-person celebrations and temple visits were either reduced in number, limited in capacity, or cancelled because of the pandemic. Given the new importance of Jain online platforms, I address their potential role in both blurring sectarian boundaries and creating sacred spaces. On the individual level, I examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the everyday religious practices of Jains. I conducted eight semi-structured interviews over Zoom between November 2020 and January 2021. I argue that while there is a great diversity of individual Jain responses, a common feature appears to be a significant increase of Jains participating in scholarly religious activities. In terms of the ways in which some Jains talk, write, and reflect on the COVID-19 pandemic, I identify and examine a Jain discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic that is characterized by environmental concerns and by the processes of scientization and universalization. Building on the work of Knut Aukland (2016) that examines the role of science in contemporary Jain discussions, I define scientization as the ongoing process where Jains underline the convergence of their religion with modern science. With the term universalization, I refer to the noticeable trend among Jains to argue for the need to teach Jainism beyond the Jain community by showing its contemporary relevance and applicability to overcome global problems, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jainism, scholarly religious activities, environmentalism, scientization, COVID-19 pandemic, universalization

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is in many respects the first global event in human history. Since January 2020, when the World Health Organization declared the outbreak an international public health emergency, the pandemic has in some way or other affected almost everybody. Branko Milanovic, an expert of socio-economic inequality, put it thus: “If, in a couple of years—when hopefully it is over and we are alive—we meet friends from any corner of the world, we shall all have the same stories to share: fear, tedium, isolation, lost jobs and wages, lockdowns, government restrictions and face masks. No other event [in human history] comes close.”1 While the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on societies have yet to come into full focus, it is clearly a historic event. As such, it is an important moment to document.

Till date, there are only a handful of studies that examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Jain religious tradition.2 The purpose of this article is to contribute to this emerging and important field of research by offering an examination of Jain practice and discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S.A. and India (March 2020 – January 2021). As such, it seeks to complement the work of both Vekemans (2021) and Donaldson (forthcoming) that examines the early responses of Jain organizations in London and in North America respectively, as well as the research of Bothra (2020) and Prajñā (2021) that address the question how certain Jain ascetic communities in India adjusted to the life-style changes required during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In part I, I focus on Jain practices. On the institutional level, I analyze the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Jain religious organizations in the U.S.A. The choice to focus on Jain organizations in the U.S.A. is informed by the fact that at the time I was conducting the research presented in this paper, I was living in the U.S.A. and teaching an academic course on Jainism, which involved a unit on “Jainism and the pandemic” (see also Maes 2022). In this section on Jain practices, I show how Jain temples and centers made extensive efforts to connect digitally with their community members when collective, in-person celebrations and temple visits were either reduced in number, limited in capacity, or cancelled because of the pandemic. I further argue that the Jain online religious platforms can blur sectarian boundaries and create authentic but temporary sacred spaces. On the individual level, I examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the everyday religious practices of Jains. To map out the personal experiences of Jains of the pandemic, I conducted eight semi-structured interviews over Zoom between November 2020 and January 2021. Given that in online interviews any geographical distance gets bridged in just one click, I took advantage of this fact by interviewing both Jains in the U.S.A. and in India. I argue that while there is a great diversity of individual Jain responses, a common feature appears to be a significant increase of Jains participating in scholarly religious activities.

In part II, I conduct a discourse analysis to examine the ways in which some Jains talk, write, and reflect on the COVID-19 pandemic. I identify and examine a Jain discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic that is characterized by environmental concerns and by the processes of scientization and universalization. Building on the work of Knut Aukland (2016) that examines the role of science in contemporary Jain discussions, I define scientization as the ongoing process where Jains underline the convergence of their religion with modern science. With the term universalization, I refer to the noticeable trend among Jains to argue for the need to teach Jainism beyond the Jain community by showing its contemporary relevance and applicability to overcome global problems, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

It bears to note that while some of the developments I discuss in this paper, such as the boom of online lectures, are directly linked to the COVID-19 pandemic and the concomitant restrictions of holding in-person temple activities and community events, others build upon earlier pre-COVID trends, such as the development of an environmental ethic and the processes of scientization and universalization.

Part I: Jain Practices and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Institutional Responses

In the U.S.A., the federal government, under both the presidency of Donald Trump (January 20, 2017 – January 20, 2021) and the current presidency of Joe Biden, never issued a nationwide stay-at-home order. While the Trump administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued several coronavirus guidelines, these remained on the level of recommendations with no enforceable mandate. The implementation of the federal guidelines has been left to the discretion of state and local authorities. The result is a great diversity in policy responses among the various states. As one commentator put it: “50 different governors [have been] doing 50 different things.”3

During the stricter lockdown period (19 March – mid-May 2020), some states explicitly banned religious gatherings and asked religious organizations to temporarily shut down physical facilities.4 Others prohibited religious gatherings only implicitly through orders regulating the maximum size of in-person gatherings or by qualifying houses of worship as “nonessential businesses.” On the other hand, several states allowed religious services to continue during the COVID-19 pandemic. The State of New York, for instance, exempted religious organizations from its stay-at-home orders, fearing that a ban on religious gatherings would violate the constitutional rights of individuals to freely exercise religion, granted under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment (Brannon 2020, 3).

Given these divergent regulations, it is not surprising that religious organizations in the U.S.A. responded in a variety of ways. A few houses of worship defied gathering bans, holding services despite state quarantine orders. Several religious organizations also filed lawsuits, arguing that their constitutional rights regarding the free exercise of religion and freedom of speech were violated, or contending that state and local governments were not neutral in their application of gathering bans, claiming that some gave more leeway to secular gatherings in comparison to religious ones (Brannon 2020, 3). Most religious organizations, however, complied with the coronavirus-related emergency orders. Many have been making extensive efforts to reach their faith members in alternative ways, from offering remote services through online streaming, radio broadcasting, and phone conferencing to drive-in services where congregants drive to a common location and worship together from the safety of their cars.5

Amidst these various regulations and organizational responses to the public health crisis, this paper focuses on the response of the Jain community. How did Jains in the U.S.A. navigate the COVID-19 pandemic? Which measures did Jain organizations take? I address these questions by means of a case study of the Jain Center of Northern California (JCNC). I start with a description of the common temple activities held at the JCNC prior to the pandemic, before proceeding to analyze the changes brought about by the spread of COVID-19. After having been closed for nearly one year, the JCNC reopened its temple complex in March 2021 with modified services. I discuss this reopening by highlighting specific guidelines of the California Department of Public Health for the reopening of houses of worship that impact the religious practices of Jains.

Jains in the United States

In the 1940s, a few Jains, mainly male students, settled in the United States. The first significant wave of migration, however, was only in the late 1960s, when the United States liberalized its immigration policies for Asian, African, and other countries. The U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 initiated the emigration of especially highly skilled and educated Jains from India and East Africa (Vekemans 2019a, 174–75; Vallely 2002, 194–97). Since then, the Jain diaspora community in the United States has grown considerably, though its exact number has “always been somewhat of a mystery” (2019a, 176). While popular estimates assess the Jain population in the United States to be around 150,000 to 200,000, the “World Religions Database at Boston University estimates the 2020 population of Jains in the United States at 97,000” (Donaldson forthcoming, 5).6 In comparison, India has nearly 4.5 million Jains (Census of India 2011).

There are over seventy Jain centers in the United States. About fifty of these also have a temple. From the end of March 2020 onward, Jain centers and temples in the U.S.A. either closed entirely, suspending all in-person activities, or remained open but with imposed restrictions in accordance with the coronavirus guidelines of their specific state and county. For instance, both Jain temples in California, the Jain Center of Northern California (JCNC) and the Jain Center of Southern California (JCSC) closed their premises “for all visitations indefinitely until further notice.”7 In Massachusetts, on the other hand, the Jain Sangh of New England remained open but required members to reserve their place online to limit the numbers of attendees “as per the State of Massachusetts guidelines” and to social distance, wear masks, and use hand sanitizer.8 Whether Jain places of worship were closed or open with restrictions, all tried hard to reach their members in different ways by offering alternatives to in-person temple visits.9

Daily Temple Worship at the JCNC Before the COVID-19 Pandemic

Within its temple complex, the JCNC has mūrtis (consecrated images) belonging to various Jain sects: the Śvetāmbara, the Digambara, and the Śrīmad Rājacandra traditions.10 Prior to the pandemic, Jains belonging to these three traditions could perform daily darśan, which is the auspicious and the reverential viewing of sacred images. For image-worshipping Jains, darśan is an essential practice (Babb 2015). Whether they visit the temple for a few minutes or a few hours, they, at the bare minimum, will perform darśan. “For many Jains,” as I explained elsewhere, “[darśan] is a reflexive act. It is a viewing that reminds one of the qualities of the Tīrthaṅkara [or of other sacred figures] one ought to develop in one’s own life” (2020a, 11).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the JCNC used to host religious activities and celebrations of both image-worshipping and non-image-worshipping Śvetāmbara sects (such as the Sthānakavāsī and the Terāpanthī), the Digambara, and the Śrīmad Rājacandra traditions. For all image-worshipping Śvetāmbara Jains, the JCNC facilitated the worship of the principal Tīrthaṅkara images, enabling every morning the rites of abhiṣeka, candana pūjā, and āṅgī.11 Every evening, the JCNC also organized ārtī.12 It further provided accommodations to those who wished to perform the ritual of pratikramaṇa, which is a ritualized repentance for the harm committed to the realm of living beings. Monthly, it arranged several religious activities for the entire Śvetāmbara community, ranging from bhāvanā (contemplation on a particular theme) and bhakti (devotion) sessions, to the collective performance of worship rites (such as snātra pūjā and ārtī) and the communal recitation of mantras (such as the namokar mantra jap). For Digambaras, the JCNC made similar provisions. The temple has images fit for Digambara worship. Daily, it used to provide the necessary materials for Digambara devotees to perform abhiṣeka and aṣṭa dravya pūjā (“worship with eight substances”). Monthly, it used to coordinate a communal worship for the entire Digambara community. For followers of the mystical poet and reformer Śrīmad Rājacandra, the JCNC used to organize, twice monthly, a recitation of his celebrated Ātmasiddhi. For the non-image-worshipping Śvetāmbara sects, the JCNC held twice-a-month meditation sessions (prekṣā) for Terāpanthīs and a namokar mantra jap for Sthānakavāsīs.13

Regarding the celebration of important religious festivals, the JCNC used to organize the yearly rainy season festival for both the Śvetāmbara and the Digambara community, called paryuṣaṇa and daśa-lakṣaṇa-parvan, respectively. Before the COVID-19 lockdowns, devotees, during these festivals, often spent parts of their days together in the temple performing the repentance ritual of pratikramaṇa and listening to religious sermons and the recitation of sacred texts. During these festivals, some Jains usually fast for a certain length of time. Dedicated lay followers may fast for the entire eight-to-ten-day long festival and drink only boiled water. The most sacred day of the year for Śvetāmbaras and Digambaras is the final day of this rainy season festival, called Saṃvatsarī. On this day, Śvetāmbaras collectively perform the repentance ceremony, known as the saṃvatsarī pratikramaṇa. Digambaras perform kṣamāpanā, a similar communal confession ceremony. Both these ceremonies used to be held at the JCNC temple complex. Other Jain festivals that used to take place yearly at the JCNC include the celebration of the birth of Mahāvīra (Mahāvīra Jayantī) and his final liberation (Dīvālī). For the Sthānakavāsī and the Terāpanthī, the JCNC also used to organize daily repentance rituals during the rainy season festival and the biannual nine-day Āyambil Oḷī festival.14

This leniency of the JCNC to accommodate various Jain sects within a single temple complex is not unusual in the Jain diaspora. Jain temples and centers in North America sometimes accommodate mūrtis of different sectarian traditions and organize events around religious festivals specific to various Jain sects. Among the diaspora community, sectarian affiliation is not as strong an identity marker as among Jains in India, even though this seems to be changing even there.15 When I asked my American respondents about their sectarian affiliation, I received answers ranging from “I used to know this” to “we are the ones who worship images” and “there are no sects in Jainism.” Such answers, typically from young Jains, show how sectarian affiliation is either unknown or downplayed as irrelevant. It is important to note that the pandemic might further deepen this blurring of sectarian identities. As I discuss below, the pandemic prompted a large-scale shift to online platforms for conducting religious services and hosting cultural-religious programs and educational events. Unlike in-person activities where one is constrained by one’s physical location, online events can be attended by everyone, no matter where one lives and one’s sectarian denomination.

The JCNC’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: From Temple Complex to Online Platforms

When the JCNC closed its temple premises because of the pandemic, it was quick in adopting Zoom to reach its community members online. Only a few days after the governor of California issued a stay-at-home order, the JCNC offered daily bhakti, svādhyāya (religious education) and shibir (workshops) over Zoom, with sessions especially for children and others aimed at the entire community for a period of two weeks.16

Since 2003, the JCNC has been offering its community members virtual darśan. While this digital service had initially a limited capacity,17 today, after successful fundraising campaigns, there are five webcams livestreaming 24/7 footage of the temple’s main images. Similar to the in-person temple activities, the JCNC offers virtual darśan images for Jains of various denominations; it has three webcams livestreaming Śvetāmbara images, one webcam livestreaming Digambara images, and another livestreaming images of the Śrīmad Rājacandra tradition.18 Given the limited numbers of recorded viewers, the popularity of virtual darśan is yet to be shown, at least among the diaspora community.19 If, however, it gains acceptance because of the pandemic-induced digital turn, its effect on blurring sectarian boundaries in veneration practices is worthy of investigation. The JCNC broadcasts the five webcams on two separate channels.20 One channel alternates images every six seconds, rotating not only between Śvetāmbara, Digambara, and Śrīmad Rājacandra images, but also bringing all the different images together on one screen at the end of a rotation round (Fig. 1).21 Inadvertently, Jain devotees using this digital resource for darśan perform auspicious viewing for all sectarian images, regardless of their own sectarian affiliation.

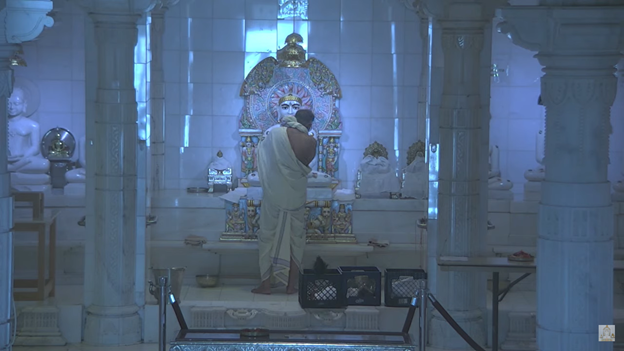

Every morning, the webcams also livestream pūjā and ārtī. As community members were not allowed to worship inside the temple during the lockdown, the JCNC ensured that the pūjārī (ritual assistant) performed daily pūjā for the consecrated Śvetāmbara images as well as ārtī. Traditionally, a pūjārī helps Śvetāmbara Jains perform their daily worship by cleaning and preparing the images and pūjā implements. However, with the temple closed to visitors, the pūjārī was now standing in for the absent devotees (Fig. 2). Those wishing to participate in these rites from the safety of their homes and, in the words of the JCNC committee, accumulate “virtual laabh,” or virtual merit, could do so by watching the livestreams.22 Similarly, for the Digambara images the JCNC appointed a Digambara volunteer to perform daily worship.

For the yearly landmark celebrations, such as the rainy season festival (the Śvetāmbara paryuṣaṇa and the Digambara daśa-lakṣaṇa-parvan), the birth of Mahāvīra (Mahāvīra Jayantī) and his final liberation (Dīvālī), the JCNC organized cultural-religious events over Zoom. For Dīvālī, for instance, the JCNC partnered with the JCSC to offer an online Dīvālī program, inviting Jains of both centers as well as from other places in California to participate. It further livestreamed various bhāvanā and bhakti performances.

Reopening of the JCNC: Limitations and Challenges

One year after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the previously closed Jain temples in the U.S.A. reopened with modified services and limited capacity. The JCNC reopened in March 2021, but it only allowed devotees to perform darśan (Fig. 3). This, as we will see, is in line with the official guidelines issued by the State of California for places of worship.

In July 2020, the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) issued detailed guidelines for the reopening of places of worship.23 Many of these are by now familiar prevention measures, such as ensuring that disposable gloves, facemasks, and hand sanitizer are available; the screening of visitors for symptoms; and the regular cleaning and disinfecting of high traffic areas. A few guidelines, however, are unique to places of worship and may, in the long term, effect significant changes in the worship practices of Jains. Given the fact that singing and chanting activities increase the chance “for transmission from contaminated exhaled droplets,” the CDPH ordered “[p]laces of worship […] [to] discontinue indoor singing and chanting activities” (CDPH, 8). Instead, it encouraged places of worship to continue such practices “through alternative methods (such as internet streaming)” (CDPH, 3). With respect to the use of material objects in rituals, the CDPH discourages both the sharing and the reuse of items in worship. For example, the CDPH guidelines advise places of worship to:

Discourage sharing items used in worship and services (such as prayer books, cushions, prayer rugs, etc.) whenever possible and provide single use or digital copies or ask congregants/visitors to bring personal items instead. (CDPH, 8)

Discontinue passing offering plates and similar items that move between people. Use alternative giving options such as secure drop boxes that do not require opening/closing and can be cleaned and disinfected. Consider implementing digital systems that allow congregants/visitors to make touch-free offerings. (CDPH, 10)

Consider limiting touching for religious and/or cultural purposes, such as holding hands, to members of the same household. (CDPH, 11)

Consider modifying practices that are specific to particular faith traditions that might encourage the spread of COVID-19. Examples are discontinuing kissing of ritual objects, allowing rites to be performed by fewer people, avoiding the use of common […] [items] in accordance with CDC guidelines. (CDPH, 13)

It is not difficult to see how these CDPH guidelines directly impact the worshipping practices of Jains. Many of the rites I mentioned earlier, such as ārtī (the offering of lamps to a sacred image), are performed collectively. To share the merit of ārtī, several Jains, usually from multiple households, hold the tray with the candle together. Many rites that are performed individually, such as the worship of sacred images with material substances (the aṣṭa dravya and the aṣṭaprakārī pūjā), also go against the CDPH guidelines as others, performing the rite later, touch the same sacred image. On the other hand, darśan or auspicious viewing is in line with the CDPH guidelines. This is why the JCNC, when partially reopening its temple complex in March 2021, only allowed darśan. The question whether the CDPH guidelines will effect only temporary or also long-term changes needs to be followed up with future research.

Individual Responses

How did Jains experience the lockdowns, the (partial) closure of their temples, and the large-scale introduction of new digital platforms for religious activities? To examine the way the COVID-19 pandemic has been impacting the everyday religious practice of individual Jains, I draw in this section from the eight semi-structured interviews I conducted over Zoom between November 2020 and January 2021. I interviewed four Jain householders from the U.S.A. and four from India. I knew four respondents beforehand (convenience sampling), while I selected the others on the basis of age (criterion-based sampling). Among the eight respondents, there are first-generation, second-generation, and third-generation diaspora Jains, as well as Indian citizens in their early forties, mid-sixties, and late seventies. Before the pandemic, two respondents used to go to the temple daily, one used to regularly take darśan of ascetics, while the remaining respondents either went weekly or bimonthly and on special occasions (such as the rainy season festival paryuṣaṇa) to Jain centers like the JCNC I described above. All eight respondents possess a solid technology literacy, which in part explains, as I discuss below, their high level of participation in online scholarly religious activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In my interviews, I observed differences not only between Jains living in the U.S.A. and India, but also within one region, sect, and even household. As one interviewee pointed out: “The way the pandemic has been affecting my religious practices is different from both my mother-in-law who lives with me and from my sister who lives in a different state [in India].” If some of my interviewees negatively experienced the closure of their local temple or suffered from not being able to take darśan of ascetics, still others felt their practice did not change much during the pandemic. One respondent, for instance, in an interview held in November 2020, insisted that despite the fact that the pandemic cancelled the collective in-person celebrations of Saṃvatsarī (the final day of the rainy season festival paryuṣan) and Dīvālī in which he used to participate, and that he could not go to the temple, he did not feel that his personal practice was affected: “I am still participating in fasts and I [still] pray daily […] for me, nothing has changed.”

For many Jains, fasting is a ubiquitous practice. There are many types of Jain fasts, depending on the duration of the fast and the specific food and water restrictions. While some respondents increased their fasting practices during the pandemic, others refrained from it altogether. Four interviewees thus noted how they experienced the lockdown restrictions (in terms of travel and social activities) as an opportunity to increase their fasting practices. One young Jain student living in Houston, for instance, completed, for the first time in her life, an atthai (an eight-day long fast during the rainy season festival paryuṣaṇa), drinking only boiled water from August 15, 2020 to August 22, 2020. My interviewees motivated their fasts with both theological arguments and health reasons, arguing that the soul, unlike the body, does not need any food and that fasts are good for health. One even likened the practice of fasting to getting a vaccine. But while some thus increased their fasting, others suspended their fasting practices, counterarguing that it may negatively affect their immune system, something which should be avoided during pandemic times.

Scholarly Religious Activities

A common trend across the various interviewees pertains to an exponential increase in what I call “scholarly religious activities.” This development is in line with Vekemans’ observation that the Jain organizations in London significantly increased their number of webinars and lectures (Vekemans 2021, 12). I asked all respondents about their online religious practices (“Which religious activities have you been conducting over Zoom or other online platforms?”). For many Jains, educational activities of various kinds (pāṭhśālā, svādhyāya, reading groups, etc.) are central to their Jain religious identity.24 This is also the case for my interviewees, who view their participation in lectures and workshops on Jainism as religious practices. In addition, they also consider their active involvement in Jain organizations to be a direct extension of practicing their Jain dharma. For my interviewees, being a president, trustee, or board member of a Jain temple or society is expressive of their Jain religious identity.

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been a significant growth of Jain lectures and workshops. One respondent, in January 2021, remarked that there are so many that each day she needs to make a selection. Not only were existing Jain organizations quick to start organizing lecture series online, but several Jains established new associations.25 Ramesh Kumar Shah, founder of the RK Group trading conglomerate, created, for instance, the nonprofit organization The Jain Foundation on 6 April 2020. Since its inception, it offered over 130 talks on Jainism, given by a wide range of speakers, from scholars and corporate giants to economists and Jain ascetics. According to The Jain Foundation’s site, the lectures reached over 14,000 participants.26 It explains the reason for creating a new online platform as follows:

Technology has been used as a platform to bring forth the values of Jainism via … an App to appeal to the current generation. It has also been an endeavour to move away from preaching Jainism to highlighting the essence of what this religion stands for. A religion which today science is proving time and again to be accurate to the very last detail.27

The claim that Jainism is in line with science is a prime example of the scientization of Jainism, which I discuss in part II. The point I wish to emphasize here, however, is that The Jain Foundation is illustrative of the fact that the pandemic has effected an exponential increase of online classes organized by and for Jains. The topics vary greatly, ranging from the history and the philosophy of Jainism to the religion’s contemporary relevance and scientific nature.28

This large-scale introduction of new online platforms raises questions about its long-term influence on traditional sources of authority within the Jain communities. As seen from the mission statement, The Jain Foundation adopted technology to “move away from preaching Jainism to highlighting the essence of what this religion stands for.” If this persists beyond the pandemic, such online lecture platforms may, I suggest, give rise to new types of authority, and create new religious leader figures within the Jain community.29 In part II, I return to the ambivalent position of traditional sources of authority within the Jain discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, we need to consider how such online platforms create new avenues for Jains to be exposed to different sectarian interpretations of texts, stotras (devotional hymns), and practices. As I pointed out above, online platforms can be attended by all, regardless of one’s location or sectarian affiliation. In matters of access, they have a “democratizing potential,” as Mallapragada noted for the Hindu digital context (see Mallapragada 2010, 115; see also Vekemans and Vandevelde 2018). One respondent, based in Jaipur, India, shared, for instance, how she attended four different lectures on the Bhaktāmara Stotra since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.30 She explained how she found it fascinating to learn about the use and versions of the stotra in different Jain sects since, as she remarked, being a Śvetāmbara she had previously not been exposed to the Digambara interpretation of the stotra. While some online platforms created during the COVID-19 pandemic are strongly rooted in a specific Jain tradition or sect,31 others, like The Jain Foundation, are not and offer lectures on Jainism that are either non-sectarian or sectarian but addressed to all. These new online platforms prompt the questions how the previous offline sectarian and local sensibilities are being reproduced and to which degree they (re)structure and (re)define Jain religious spaces. While answering these questions lies beyond the scope of the current study, it is worth noting that “the Internet complicates,” as Vekemans observes, “geographic locationality, at times reproducing hyper-local practices and sensibilities, at other times utterly geographically untethered” (Vekemans 2021, 16). The same may be said in terms of sectarian boundaries. While (the new Jain) online platforms can reproduce the pre-existing offline sectarian or, in case of organizations such as JAINA, non-sectarian Jain identities, they can also blur and break such boundaries. Reflecting on the digital relocation of the Jain organizations in London during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Vekemans argues that “Some of the factors that divide Jains into subgroups based on gender, language, sect, geographic location, and even migration history become less consequential (or at least easier to circumnavigate) when activities and events are removed from their in situ localization and transported to the online realm, opening up possibilities of global participation and potentially strengthening ideas of a unified Jain community” (2021, 16).

Online Pūjā

One respondent, a lay Digambara Jain living in New Delhi, specifically missed not being able to go to the temple during lockdown. Before COVID-19, his daily routine consisted of performing samāyik for 15 to 20 minutes in the early morning,32 followed by a 45-minute morning walk, a bath, and a visit to his local temple to perform pūjā. On Sundays, he used to listen to the teachings of sādhus (pravachans) and teach young Jains about Jainism at the local school (pāṭhśālā). With his local temple closed, he started to livestream temple pūjās on his TV instead. Since then, every morning, he has been performing his daily pūjā to the Tīrthaṅkara images that are livestreamed on Jinvani, an Indian television channel of the Digambara sect to which he belongs (Fig. 1). To go through the various pūjā steps and mantras, he uses an app on his phone.33 To stay focused he turns off the TV sound. For this respondent, the livestream is not so much about being a passive observer of the live pūjā; he considers the livestream valuable insofar as it enables him to actively perform his own pūjā. The COVID-19 pandemic has thus exposed him to new digital modes of practicing his religion. Reflecting on his altered religious practices, he said with a sigh that “unfortunately, technology is very helpful” and while “it is not like [performing pūjā] in the temple, this is as close as you can get.”

Steven Hoover and Nabil Echchaibi (2014) introduced the concept of “third spaces” to refer to “religious venues that exist between online and offline settings, venues that believers approach as if they are authentic spaces of religious practices” (Campbell and Evolvi 2020, 7). While “third spaces” thus exist between online and offline settings, their “authenticity” or “sacredness” is acquired by their (real, imagined, or fabricated) links to offline, “real-life” spaces (Mallapragada 2010, 116–17). In their study of the role of online temple worship among diaspora Jains in 2018, Vekemans and Vandevelde observed how online temples are often “tied to the real world by the use of a picture of a recognizable murti of a famous temple or pilgrimage situation” (Vekemans and Vandevelde 2018, 190). Considering these facts, I think it is apt to conceptualize the religious space that the livestreaming effects each morning on my respondent’s TV screen as such a “third space,” the sacredness of which is established by its link to real, but offline, mūrtis. That he considers this space as an authentic religious venue is visible in the fact that he ritually approaches the livestreaming as if he were in the temple. To go to the temple, Jains traditionally take a bath and wear pūjā clothes. For men, traditional pūjā clothes can consist of unstitched orange or, if they are under the vow of continence (brahmacarya), white robes (dhotī), but any set of clothes set aside for pūjā can be worn. The main point is that the clothes one wears for pūjā are not worn for other activities. Pūjā clothes need to be “ritually pure.” To ensure this, a Jain traditionally takes a bath before putting the pūjā clothes on and, once in pūjā clothes, refrains from worldly, nonreligious activities, such as taking water and food, engaging in chitchat, or going to the bathroom. Observing these multiple restrictions surrounding pūjā clothes, Whitney Kelting (2001, 126) argues that the creation of sacred space starts with the donning of the pūjā clothes itself:

While the pūjā space can often be most clearly marked by the lack of idle conversation and the items left outside (and, of course, the pūjā rituals themselves), the demarcation of pūjā time is most clearly represented by the donning of pūjā clothes.

She further notes how during her fieldwork she witnessed a mother scolding her daughter for hitting her sister who was in pūjā clothes and about to go to the temple, observing that “[h]itting her sister in pūjā clothes was like hitting her in the temple” (Kelting 2001: 127). This anecdote illustrates well the power of pūjā clothes in effecting a sacred, religious space.

Given this ritual significance of pūjā clothes, it is important to observe that my respondent would take a bath and “change his clothes” before livestreaming the pūjā. In other words, in terms of ritual preparations, he makes no distinction between the livestreaming and the temple. The livestreaming thus seems to transform his living room into a temporary yet authentic sacred space. Despite this, my respondent negatively experienced not being able to go to his local temple during the lockdown, explaining that the aura of the temple is instrumental in supporting his best pūjā practices. He clarifies: “I may be the primary cause of my actions, but there is also the efficient cause. The aura of the temple helps you. At home, if I feel thirsty [while performing pūjā], I take a glass of water.” For this respondent, the livestreaming is only a temporary, crisis-induced solution, which cannot fully replicate the experience and benefits of performing pūjā in his local temple.34

Everyday Jain religious practice ranges from darśan and temple worship (pūjā) to fasting (tapas) and attending lectures on Jainism. Given the flexibility and fluidity of Jain practices, it is not surprising to see that the COVID-19 pandemic has been impacting the everyday religious activities of various Jains differently. In general, the way the COVID-19 has been impacting the religious activities of Jains depended on how their daily religious practice looked like before the pandemic, their technological literacy, amount of free time, social networks, and their level of engagement in local and (inter)national Jain communities.

Part II: Jain Discourse and the Pandemic

Jains give various explanations for the COVID-19 pandemic. With regards to the diaspora context, one scholar observes that “North American Jains admit a diversity of Jain philosophical perspectives on the pandemic” (Donaldson forthcoming, 2, see also 10-11). Many Jains considering the pandemic’s origin tend to acknowledge the dominant scientific narrative that explains the COVID-19 as a novel type of coronavirus that initially jumped from an animal source to humans before starting to spread between people. Many Jain accounts, however, do not end here, but discuss the deeper causes behind the pandemic and identify solutions to prevent future ones. It is in these discussions that a Jain lens on the pandemic becomes perceptible. Many Jains claim that the cause of the pandemic is a lack of adherence to Jain principles, such as non-violence (ahiṃsā) and non-possessiveness (aparigraha). Consequently, they suggest that the adherence to these principles can offer a solution. As one author writes: “The whole mankind would not have suffered by the COVID-19 pandemic if they would have followed the Jain teachings and moral values and virtues” (Garai 2020, 50).35 This section takes a closer look at one distinctive Jain discourse on the pandemic that is characterized by environmentalism and the processes of scientization and universalization.36 I expound these three characteristics individually before exemplifying my argument with a case study.

Environmentalism

The Jain discourse under analysis is marked by environmental concerns. Many Jains consider the COVID-19 pandemic as being symptomatic of a broken ecosystem. They view it as manmade, being the result of the world’s overexploitation of natural resources. As a theological explanation, several Jains writing and reflecting on the causes of the COVID-19 pandemic bring in the law of karma.37 Connected to this, they imbue nature with a moral force and agency, suggesting that the pandemic is the revenge of an abused planet earth or that it is the outcome of nature trying to teach everyone a lesson.

For example, in his video “Say No to More: A 3 Step Solution to Climate Change” posted in September 2020, Rahul Kapoor Jain, an international motivational speaker, mindset coach, and author,38 sees the current crisis in the following terms: “[W]hat you give is what you get, and what you get is what you deserve. This is the law of karma. Anything said or done in this world, is echoed back with the same intensity. This ecological crisis that we are all facing, is an echoing back of our own thoughts, words, and actions.”39 For many Jains, like for Rahul Kapoor Jain, the disturbed ecosystem springs forth from a disturbed human morality. In another video, “Get Back into Your True Nature,” published online on 15 May 2021, he further suggests that the coronavirus was purposefully created by nature “with the intention that we will think about our mistakes and make amends.” He explains “our mistakes” as the misuse of nature’s resources and its pollution caused by “the viruses of anger, ego, greed, and deceit.”40

Within this Jain environmental discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic, the principle of ahiṃsā (non-violence) is presented as a means to not only prevent future pandemics but also to overcome climate change. In this discourse, the principle of non-violence is first and foremost equated with a vegetarian diet and an active care for and restoration of the environment. This pandemic-contextual interpretation of ahiṃsā reinforces the sociocentric and ecocentric ethos in Jainism, which began to emerge in the 2000s as a prominent discourse among diaspora Jains about twenty years ago.

Traditionally, the central ethic of ahiṃsā mirrors the ascetic ideal of renunciation. Aiming to purify the soul, it is focused on self-realization. Anne Vallely dubbed this orthodox interpretation of ahiṃsā a “liberation-centric ethos” (2002, 193). By contrast, in recent years, a new interpretation of ahiṃsā emerged, involving a “discourse of environmentalism and animal rights” (Vallely 2002, 193). Nonviolence, from this perspective, is not so much about the purification of the soul as it is about “alleviating the suffering of other living beings” (Vallely 2002, 205). Vallely aptly terms this interpretation of ahiṃsā a “sociocentric and ecocentric ethos” (2002, 193, 203–13), observing the emergence of this new ethical orientation among some Jain communities already twenty years ago. At that time, this environmental interpretation of ahiṃsā marked a sharp difference between not only diaspora Jains and Jains in India, but also among the first- and second-generation diaspora Jains (Vallely 2002, 204–5).

In comparison, in the Jain discourse under discussion, environmentalism has become a pan-Jain theme. It is no longer uniquely characteristic of young western Jains. Contemporary Jains, whether living in India or elsewhere, whether first-, second-, or third-generation diaspora Jains, frequently express Jain principles in a language that stresses the importance of both maintaining a healthy ecosystem and protecting animal rights, showing the interconnectedness between human, animal, and plant life.

Scientization

Knut Aukland coined the term “scientization” to refer to “processes by which adherents of religions align their religion with the natural sciences” (2016, 194). He argues that appeals to the authority of science can be both in form and content, explaining how “[a]ppeals in form are found in the deployment of scientific-looking diagrams and scientific-sounding terminology, while appeals in content consist of claims that one’s religion is ‘scientific’ or ‘a science’” (2016, 199). In the discourse under analysis, both types of appeals occur frequently and in a variety of ways.

Appeals in form can comprise accounts that show the benefit of traditional Jain tenets for today’s society by explaining these in a scientific, modern, rational, or health-oriented language. With respect to online talks and videos, typical examples of appeals in form are images of hi-tech or modern research centers. For example, in “Say No to More,” the video I mentioned earlier, Rahul Kapoor Jain uses a collation of scientific diagrams and animations, such as a NASA simulation, to explain the greenhouse effect, next to pictures and short films of western industry, agriculture, livestock farming, and deforestation (Fig. 1).

Appeals in content include claims that Jain principles and practices are scientifically proven solutions to the pandemic (and other world problems). Auckland classifies such types of appeals as “unspecific” (2016, 203–4). While they state that Jainism is scientific,41 there is no systematic attempt to show why Jainism and science are in apparent harmony or why its principles are scientifically proven means in overcoming the pandemic. On the other hand, in the discourse under analysis, appeals in content can also involve arguments that show the global need and relevance of Jainism in an entirely scientific fashion, from formulating a hypothesis and collecting facts, to offering an analysis of these facts and making scientific generalizations. In contrast to “unspecific” appeals, I call these types of arguments “specific,” as their authority rests on a scientific argumentation.

Within this Jain scientific discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional sources of authority have, I argue, an ambivalent position. Jains who wish to substantiate their claims by means of a traditional source of authority have a wide range of options available, from quoting the words of Tīrthaṅkaras and sacred texts, to referring to well-respected historical figures and ascetic leaders (ācāryas) of their community. Some Jains who write on the COVID-19 pandemic and draw upon the prestige of science leave out these traditional sources of authority. To return to our earlier example “Say No to More”: Rahul Kapoor Jain does not refer to any traditional Jain source of authority, be it the Tīrthaṅkara Mahāvīra, a particular Jain scripture or ascetic. Also in his video’s imagery, there is no characteristic Jain image in sight. The result is a Jain discourse on climate change and COVID-19 presented in a scientific and universal language. Others, however, unlike Rahul Kapoor Jain, can rest their claim that Jainism is scientific on the authority of a traditional source itself. One respondent, for example, told me how his ācārya says that the practice of Jainism is scientifically based and helps one avoid contracting disease. That Jainism is scientific and good for health rests, in this example, on the ācārya’s authority. In the scientific discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional sources of authority are thus either ignored or drawn upon to rest one’s claim that Jainism is scientific and pertinent for today’s world. The choice of individual authors whether or not to appeal to traditional Jain sources of authority may be determined by their prospective (and imagined) audience, by their active endorsement (or rejection) of the scientization and universalization discourses within Jainism, and, in case their contribution was upon invitation, the views of those Jains who commissioned their work.

Universalization

With the term “universalization” I refer to the ongoing trend where Jains actively seek to promote the Jain way of life to non-Jains. While proselyting is not a part of the contemporary Jain agenda, there is this common idea that if more people knew about Jainism, the world would be less violent, greener, healthier, and more peaceful (see, e.g., Jain, Rahul, 15 May 2021 and 28 September 2021; R. Jain 2020; Jainuine YouTube Channel, 4 November 2019; Kumar 2018; Prajñā and Samanta 2015). As one respondent, living in New Delhi, said: “The basic tenets of Jainism should be widely publicized. They are useful, scientific, ecofriendly and they promote harmonious co-existence of human beings and animals.” Similarly, Dipak Doshi, former Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Jain Society of Metropolitan Chicago (JSMC), in an interview with Young Minds for a special issue on Jainism and the pandemic, stated: “In the past 40+ years here in Chicago, I have witnessed Jainism evolve and mature, however, we have kept it predominantly confined to our temples and communities. It is time to take Jainism on a roadshow, educating the mainstream by showcasing Jainism and its values and principles” (Young Minds 2020, 7).

With respect to the COVID-19 pandemic, examples of universalization include claims that Jainism offers universal solutions and tools to both endure and overcome the pandemic. Many Jains thus feel that Jain principles, especially the principle of non-violence (ahiṃsā), should be spread beyond the Jain community (see, e.g., S. Jain 2020; Kumar 2018; Sanchetee and Sanchetee 2020). Underlying the process of universalization seems to be the assumption that non-Jains do not practice ahiṃsā simply because they do not know about it or because they have a misinformed dietary view about the need of meat consumption. It is interesting to note that in the past, Jains who were actively proclaiming the need to promote Jainism were mainly lecturing for Jain audiences and writing for journals, magazines, and websites published by and for Jains. In recent years, however, this audience has become diverse and international, consisting of both Jains and non-Jains alike. This, I argue, is due to the “academization” of Jainism.

Aukland (2016, 209) defines “academization” as the “processes by which proponents of a religion establish institutions and practices modeled on mainstream academia, actively use markers of such institutions and their scholars, and invite academic appraisals of their religion.” He further notes how some of these institutions can work together with recognized universities in India and abroad (Aukland 2016). The example of the Bhagawan Mahavira International Research Centre shows how the universalization (as well as the scientization) of Jainism can go hand in hand with the process of academization. The center was established in 2014 at the Jain Vishva Bharati Institute in Ladnun (Rajastan, India) with the vision to “integrate science and Jain philosophy and to evolve a scientific approach to [the] understanding of Jain traditions” (ICSJP Event Brochure 2016, 2). In March 2021, the center organized the Second International Conference on Science and Jain Philosophy (ICSJP) in partnership with Florida International University (FIU). As mentioned on the conference site, the purpose of this conference was “to connect scientists working on the interdisciplinary field of consciousness studies to scholars of the Jain religious tradition […] [in] the hope to better understand the human mind and explore new pathways towards a more peaceful, just, and verdant world.”42 Participating in the conference were Jains, many of whom have a background in the natural science or the humanities, but also western scholars of Jainism and scientists. This collaboration of Jains with western scholars and scientists is a typical aspect of the academization of Jainism (see Aukland 2016, 211).

Case Study: “Corona Pandemic in the Perspective of Non-Violence”

In this section, I analyze the article “Corona Pandemic in the Perspective of Non-Violence.” The article was published in the summer of 2020 and written by Rajmal Jain, a lay Digambara who grew up in a middle-class family in a small town in Dungarpur district, Rajasthan. As a young child he went daily for one hour to pāṭhśālā, but he learned as much about Jainism from his mother who, in his words, was a “high order practicing Jain.” While he is Digambara, he did not experience the sectarian division between Śvetāmbaras and Digambaras much in his childhood. During a Zoom conversation, he explained that he used to eat at both Śvetāmbara and Digambara temple bhojanālay (“restaurants”) and that his family allowed intermarriage (both his grandmother and sister-in-law are Śvetāmbara). As a student, he studied Physics (MSc) at the then Udaipur University. Having graduated with first class, he was selected to the Ph.D. program of the Physical Research Laboratory at the Indian National Research Institute for space and allied sciences in Gujarat’s megacity Ahmedabad, where he has been living since. After a successful and international academic career in astronomy, Rajmal Jain started to dedicate himself more fully to his religion. Under the encouragement of the Digambara ācārya Kanaknandi, he began to apply his scientific education to Jainism, actively contributing to the scientization of Jainism by seeking to scientifically prove various Jain tenets, such as the doctrine of karma or, as we will see below, the importance of ahiṃsā to curb climate change and prevent future pandemics.43

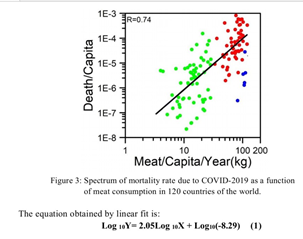

In his article, Rajmal Jain examines the correlation between meat consumption and the COVID-19 death rate in a scientific fashion. He argues that “low meat eater [sic] countries have about 4 times less mortality relative to high meat eater [sic] countries” (2020, 8). Rajmal Jain frames the COVID-19 in ways I described before as typical for the Jain discourse under analysis.

Rajmal Jain views the COVID-19 pandemic as the result of a broken ecology, which, in turn, is the outcome, he writes, of a wrecked morality. He considers the human tendencies for greed and violence as the main culprits. “Greed,” he writes, “not only destroyed trees, plants and large forests but also killed small (one sense) to big (2-5 sense) animals that are surviving on the earth, flying in the air and living inside the oceans” (2020, 2). With respects to violence, he stresses the non-vegetarian diet. Like Rahul Kapoor Jain, Rajmal Jain sees the COVID-19 pandemic as manmade and frames it within the Jain theory of karma. He further puts forward the hypotheses that the current pandemic is the “revenge by [the] geosphere or [the] biosphere” and that it is a lesson of Mother Nature teaching us to curb the destruction, pollution, and abuse of the planet’s life and resources (2020, 3, 12).

To prove the positive correlation between meat consumption and the COVID-19 death rate, Rajmal Jain appeals to the authority of science. His article is a scholarly paper both in form and content, from formulating hypotheses to offering a scientific analysis of the meat consumption per capita of 120 countries and coronavirus statistics (Fig. 2). He bases his analysis on datasets provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization (R. Jain 2020, 3). Further, seeking to prove his hypothesis that the pandemic may be the karmic retribution for the killing of animals, Rajmal Jain investigates the theory that animals, when slaughtered, disperse infrasonic waves which, in due time, “take revenge.” Regarding this point, he concludes:

We interpret our spectrum results … in the perspective of infrasonic wave energy deposited in the ecosphere as a consequence of [the] killing of a large number of animals by man every day. Obviously, high-power deposition from emotional tension infrasonic waves took place in high meat-eating countries and thereby according to karmavāda, the high mortality rate [due to COVID-19] has also been observed in these countries. So we may interpret that the current corona pandemic is the revenge by animals and all other species killed by humans. (2020, 13)

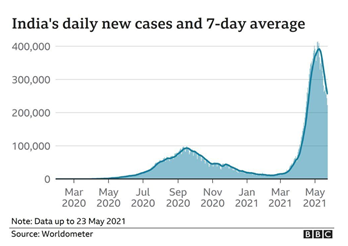

To be clear, I am not seeking to examine whether Rajmal Jain’s methodology and conclusions are scientifically valid. It is important to keep in mind that he conducted the research for his article in the summer of 2020. At that time, after a 10-week long nationwide lockdown, the government of India was implementing its second and third phase reopening plan (Unlock 2.0 and Unlock 3.0). During the pandemic’s first wave, India was not affected as severely as during the second wave, which began in March 2021 (Fig. 3). If Rajmal Jain had written his article when India became the new epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic (April 2021), his hypotheses, analysis, and results would likely have been different. The degree to which the Jain discourse on the pandemic’s second wave in India differs or agrees with the Jain discourse that emerged during the early stages of the pandemic is yet to be analyzed. The main point I wish to emphasize here is how Rajmal Jain’s article fits within the ongoing process of the scientization of Jainism. Further, as I discussed above, traditional sources of authority have an ambivalent position within this discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic, being either disregarded or, conversely, acknowledged. Rajmal Jain’s article is an example of the latter. While his article is, in essence, a scientific paper, on several occasions, he also explicitly states that Jainism is scientific and rests these claims on the authority of traditional sources, such as the first Tīrthaṅkara Ṛṣabhanātha (2020, 11).44

In line with the process of universalization, Rajmal Jain feels that Jainism should be taught to non-Jains. To overcome the current COVID-19 pandemic and prevent future ones, we all need to focus, according to Rajmal Jain, on changing our lifestyle by practicing “ahiṃsā (non-violence) as well as aparigraha (non-possession) whole heartedly” (2020, 13, see also 9, 11, 14). He explains the core Jain concept of non-violence by drawing both on the traditional, liberation-centric and the socio-and ecocentric (or environmental) interpretation of ahiṃsā. Thus, he writes: “non-violence or universal love to all living beings is the foundation of the Jain’s sacred life leading to the goal of liberation and self-realization called mokṣa” (2020, 3). Earlier in the article, we can read how applying non-violence means “stopping non-veg foods” as this “will protect our bio-sphere cycle and hence […] nature” (2020, 2). He further concludes that: “There is no need to teach non-violence to [the] Jain community. [R]ather it is […] necessary to motivate non-Jains to consider and practice non-violence in [their] daily life to save the biosphere and humanity” (2020, 11). For Rajmal Jain, there is a sense of urgency that Jainism should be spread and taught beyond the Jain community.

Conclusion

In this article, I sought to analyze the ways the COVID-19 pandemic has been impacting the Jain religious organizations in the U.S.A., as well as the everyday religious practices and public discourse of Jains in the U.S.A. and India. Given the unique nature of the COVID-19 pandemic as a historical event, it is important to document the state of affairs as it unfolds. I hope the case studies analyzed here, while limited, will enable future scholars both to better assess how the (online) religious practices of Jains during the pandemic overlap with or differ from other (online) religious practices, and to examine the long-term effects of the growth of Jain online platforms on various issues, from the question of religious authority to the ongoing democratization of access in online environments. We have seen how in terms of Jain practice, Jain organizations in the U.S.A. made considerable efforts to reach their members in various ways, from offering daily bhakti, svādhyāya, and shibir over Zoom to digital darśan. While some of these activities were offered for the first time on online platforms, others, like digital darśan, had been offered before the COVID-19 pandemic as well. Though the long-term effects of the pandemic-induced digital relocation remain to be seen, it is safe to suggest that it effected a shift of attitude towards virtual religious events. If before the pandemic online-only socio-religious events were either rare or rather negatively received in certain Jain communities, they gained in popularity and acceptance during the pandemic (see also Vekemans 2021, 11–12, 15). In our examination of the Jain Center of Northern California, we have seen how the changes and accommodations in its religious services were in line with the CDC and Californian state coronavirus guidelines. With regards to the manner in which the COVID-19 pandemic has been affecting the everyday religious practices of Jains, I showed that there is a great variation among Jains. A common feature, however, is the multifold growth of Jains participating in scholarly religious activities, which is directly linked to the fact that in-person events were either cancelled or severely limited during the early phases of the pandemic. I also discussed online pūjā, where I argued that Jain digital platforms can create authentic but temporary sacred spaces.

In the second part of this article, I identified and examined a Jain discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic that is characterized by an environmental agenda and by the processes of scientization and universalization. As we have seen, the recasting of traditional Jain tenets in an environmental language started already in the 2000s. If at that time, this was mainly a trend among second-generation diaspora Jains, the COVID-19 pandemic shows that environmentalism has today become a pan-Jain theme. The processes of scientization and universalization analyzed in this paper are also continuations of pre-COVID developments. Within the context of the pandemic, these two processes involve, as I have demonstrated, appeals to the authority of science to show the contemporary relevance of Jain principles and pleas to spread the Jain way of life to non-Jains in a collective effort to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. I further contended that traditional sources of authority have an ambiguous role within the scientization process. Several scholars have argued for considering appeals to the authority of science as a “legitimation strategy.” While this is correct it is also more than that. The process of scientization offers, as Aukland contends, “a variety of resources with which people reformulate and re-represent, explore, and reinterpret and at times re-imagine their religion” (2016, 194). When appealing to the authority of science, Jains may do so to either “defend and preserve traditional beliefs and practices,” or, conversely, “to argue against traditional beliefs and practices” (2016, 194). As I hope to have demonstrated, in the Jain discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic discussed in this paper, Jains appeal to authority of science to argue for the contemporary relevance and need of Jainism to both cope with the COVID-19 pandemic and to prevent other such global disasters in the future.

References

Aukland, Knut. 2016. “The Scientization and Academization of Jainism.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84: 192–233.

Babb, Lawrence. 2015. Understanding Jainism. Edinburgh/London: Dunedin.

Bothra, Shivani. 2018. “Keeping the Tradition Alive: An Analysis of Contemporary Jain Religious Education for Children in India and North America.” Victoria University of Wellington.

———. 2020. “Svādhyāya: A Religious Response to COVID-19.” Ahimsa Center Newsletter, 15.

Brannon, Valerie. 2020. “Update: Banning Religious Assemblies to Stop the Spread of COVID-19.” Congressional Research Service Legal Sidebar, 1–5.

Campbell, Heidi, and Giulia Evolvi. 2020. “Contextualizing Current Digital Religion Research on Emerging Technologies.” Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 5–17.

Cort, John. 2005. “Devotional Culture in Jainism: Mānatuṅga and His Bhaktāmara Stotra.” In Incompatible Visions: South Asian Religion and History in Culture; Essays in Honor of David M. Knipe, edited by James Blumenthal, 93–115. Madison, WI: Center for South Asia/University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Donaldson, Brianne. 2019a. “Transmitting Jainism Through U.S. Pāṭhaśāla Temple Education, Part 1: Implicit Goals, Curriculum as ‘Text,’ and the Authority of Teachers, Family, and Self.” Transnational Asia: An Online Interdisciplinary Journal 2 (1): 1–45.

———. 2019b. “Transmitting Jainism Through U.S. Pāṭhaśāla Temple Education, Part 2: “Navigating Non-Jain Contexts, Cultivating Jain-Specific Practices and Social Connections, Analyzing Truth Claims, and Future Directions.” Transnational Asia: An Online Interdisciplinary Journal 2 (1): 1–45.

———. forthcoming. “Unifying, Globalizing, and Reinterpreting ‘Practical Nonviolence’ Through the COVID-19 Pandemic Response of North American Jains.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 26 (3).

Garai, Subhas. 2020. “Practical Jainism & Pandemic.” International School for Jain Studies (ISJS) – Transactions 4 (3): 48–54.

Hoover, Steven, and Nabil Echchaibi. 2014. Media Theory and the “Third Spaces of Digital Religion”. Colorado Boulder: University of Colorado Boulder: Center for Media, Religion, and Culture.

Jain, Pragya, and Sayyam Jain. 2020. “Pandemic and Akartāvāda.” International School for Jain Studies (ISJS) – Transactions 4 (3): 49–55.

Jain, Rajmal. 2020. “Corona Pandemic in the Perspective of Non-Violence.” International School for Jain Studies (ISJS) – Transactions 4 (3): 9–22.

Jain, Shugan. 2020. “Minimizing a Pandemic’s Impact.” International School for Jain Studies (ISJS) – Transactions 4 (3): 42–48.

Kelting, Whitney. 2001. Singing to the Jinas. Jain Laywomen, Maṇḍal Singing, and the Negotiation of Jain Devotion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kumar, Chiranjib. 2018. “Jain Philosophy: One Solution for All Global Problems.” In Conference Paper. Karnataka: Shravanabelgola.

Maes, Claire. 2020a. “Jain Education in South Asia.” In Handbook of Education Systems in South Asia. Global Education Systems, edited by P. M. Sarangapani and R. Pappu, 1–29. Singapore: Springer Nature.

———. 2020b. “The Pandemic and My Conversation with a Young Jain.” Ahimsa Center Newsletter, 4–5.

———. 2022. “Framing the Pandemic: An Examination of How WHO Guidelines Turned into Jain Religious Practices.” Religions 13 (5): 377. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050377.

Mallapragada, Madhavi. 2010. “Desktop Deities: Hindu Temples, Online Cultures and the Politics of Remediation.” South Asian Popular Culture 8 (2): 109–21.

Prajñā, Samanī Chaitanya, and Samanī Kanta Samanta, eds. 2015. Jainism in Modern Perspective. An Enquiry into the Relevance of Jainism in the Modern Context of the World. Ladnun: Jain Vishva Bharati.

Prajñā, Samanī Pratibhā. 2021. “Apavāda Mārga: Jain Mendicants During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies 16: 5–10.

Sanchetee, Pratap, and Prashant Sanchetee. 2020. “Covid-19 and Spiritual Technologies : Turn ‘Bane’ to ‘Boon’.” International School for Jain Studies (ISJS) – Transactions 4 (3): 23–32.

Vallely, Anne. 2002. “From Liberation to Ecology: Ethical Discourses Among Orthodox and Diaspora Jains.” In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life, edited by Christopher Chapple, 193–216. Cambridge: Harvard Divinity School.

Vekemans, Tine. 2014. “Double-Clicking the Temple Bell: Devotional Aspects of Jainism Online.” Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 6: 126–43.

———. 2019a. “Digital Religion in a Transnational Context: Representing and Practicing Jainism in Diasporic Communities.” PhD diss., Ghent: Ghent University.

———. 2019b. “From Self-Learning Pathshala to Pilgrimage App: The Expanding World of Jain Religious Apps.” In The Anthropological Study of Religious and Religion-Themed Mobile Apps, edited by Jacqueline Fewkes, 61–82. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

———. 2021. “Crisis and Continuation: The Digital Relocation of Jain Socio-Religious Praxis During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Religions 12 (342): 1–22.

Vekemans, Tine, and Iris Vandevelde. 2018. “Digital Derasars in Diaspora : A Critical Examination of Jain Ritual Online.” In Religion and Technology in India: Spaces, Practices and Authorities, edited by Axel Jacobsen, 183–200. Oxon: Routledge.

I wish to thank Alexander Agadjanian and Konrad Siekierski for their invaluable editorial input and their constructive feedback. I also wish to thank Tine Vekemans and the anonymous reviewer for their many valuable comments, corrections, and suggestions.

See “The First Global Event in the History of Humankind” by Branko Milanovic for Social Europe on 7 December 2020. Last accessed 31 July 2021. https://socialeurope.eu/the-first-global-event-in-the-history-of-humankind.↩︎

See Bothra (2020); Donaldson (forthcoming); Maes (2020b, 2022); Vekemans (2021); and Prajñā (2021). The Jain religious tradition (Jainism) originated in North India about 2500 years ago. It has a distinctive community of both male and female ascetics and a supporting community of laypeople, also referred to as householders. While fully ordained Jain ascetics live only in India, Jain householders live in every part of the world.↩︎

Andrew Noymer, Associate Professor of public health at UCI, quoted in The New York Times on 20 May 2020. Last accessed 19 March 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/20/us/coronavirus-reopening-50-states.html.↩︎

See, e.g., the Order of the Governor of the State of Maryland. 30 March 2020. Last accessed 17 March 2021. https://governor.maryland.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Gatherings-FOURTH-AMENDED-3.30.20.pdf#page=3.↩︎

See, e.g., Creative Church Arts Ideas. Last accessed 10 April 2022. https://creativechurchartsideas.org/drive-in-church-services-church-ministry-during-covid-19/.↩︎

A part of the reason why the number of Jains in the United States will remain uncertain is because Public Law prohibits the U.S. Census from gathering data on religious affiliation in its demographic surveys.↩︎

See JCSC Website. “COVID-19 updates.” Last accessed 22 March 2021. https://jaincenter.org/.↩︎

See Jain Sangh of New England Website. “Important Guidelines for JSNE Derasar Visit during COVID-19 Pandemic.”↩︎

To consider how this is in line with the responses of Jain organizations in London, see Vekemans (2021).↩︎

Śvetāmbara (“white clad”) and Digambara (“sky clad”) are the two main sects in Jainism. The denominations refer to the facts that Śvetāmbara ascetics are clad in white robes, whereas the Digambara monks wander naked. Śrīmad Rājacandra (1867–1901) was a mystical poet, lay reformer, and friend of Mahātmā Gandhi and propagated a non-sectarian form of Jainism.↩︎

Abhiṣeka is to ritually lustrate a Tīrthaṅkara image. Candana pūjā is a Śvetāmbara practice where the devotee dabs sandalwood and saffron paste on key parts of the Tīrthaṅkara image, symbolically seeking to cool her or his passions. Āṅgī is the Śvetāmbara rite of adorning a consecrated image.↩︎

Ārtī is the rite of offering lamps to a Tīrthaṅkara image.↩︎

The namokar mantra is the most sacred Jain mantra. It pays homage to the five worship-worthy beings: the arihaṃtas (omniscient ones), siddhas (liberated souls), ācāryas (mendicant leaders), upādhyāyas (preceptors), and the sādhus and sādhvīs (mendicants). Jap is the practice of meditatively repeating a mantra or sound for a set number of times.↩︎

Āyambil Oḷī is a Śvetāmbara festival, during which devotees fast by eating only one meal a day consisting of sour foods.↩︎

One respondent pointed out that the response to the pandemic by Jains in India was, in general, “non-sectarian.” This claim would need further investigation.↩︎

From 23 March 2020 to 5 April 2020. Last accessed 1 April 2021. http://www.jcnc.org/home/covid19.↩︎

In January 2003, for instance, the JCNC announced on its website that for the live webcast “there is a limit of 60 simultaneous users” and “[w]e need your financial support to go above the current capacity. Please donate…” (JCNC website on 23 January 2003, https://web.archive.org/web/20030123065031/http://jcnc.org/). I thank Tine Vekemans for bringing to my attention the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, which allowed to trace the starting date of this virtual pūjā service.↩︎

In the U.S.A., just as in India, the majority of Jains are Śvetāmbara, which most likely accounts for the fact that the JCNC has more webcams livestreaming Śvetāmbara images than Digambara and Śrīmad Rājacandra images.↩︎

On online worship practices before COVID-19, see Vekemans (2014) and Vekemans & Vandevelde (2018).↩︎

See http://www.jcnc.org/livedarshan/gabharadarshan (last accessed 30 March 2021).↩︎

This is a screenshot taken on 30 March 2021 at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boQeIdYg9hE.↩︎

On the role of pūjārīs in diaspora contexts, see also Vekemans (2021, 19, fn. 25).↩︎

See Covid-19 Industry Guidance: Places of Worship and Providers of Religious Services and Cultural Ceremonies. Last accessed 29 July 2020. https://covid19.ca.gov.↩︎

For a discussion of Jain religious education offered at pāṭhśālās, see Maes (2020a), Bothra (2018), and Donaldson (2019a, 2019b).↩︎

To give an example of each: during the COVID-19 pandemic the Gyansagar Science Foundation launched in November 2020 a monthly Zoom lecture series. The Jaina India Foundation, a sister organization of the Federation of Jain Associations in North America, launched Jain Avenue, a web-based and multimedia magazine in August 2020.↩︎

See Jain Foundation Talks. Last accessed 3 May 2021. https://www.jainfoundation.in/jain_talk_in.php.↩︎

The Jain Foundation. Last accessed 30 June 2021. https://www.jainfoundation.in/the_jain_foundation.php.↩︎

See, e.g., the following lectures hosted online during the COVID-19 pandemic by The Jain Foundation: “The Antiquity of Jain Culture in Sri Lanka and Buddhist Literature,” “Tattvarth Sutra: The Bible or Gita of Jain Religion,” “Jainism and Environmental Protection,” and “The Spiritual Science of Shri Namaskar Mahamantra.” Last accessed 30 June 2021. https://www.jainfoundation.in/jain_talk.php.↩︎

The Bhaktāmara Stotra is a Sanskrit hymn dedicated to the first Tīrthaṅkara Ṛṣabhanātha and accepted, with some variations, by both Śvetāmbaras and Digambaras. On the central role of this stotra in Jain devotional practices, see Cort (2005).↩︎

See, e.g., the Gyan Jagrati YouTube Channel, which is solely focused on the Digambara tradition as initiated by Acharya Shri Shantisagar (1872–1955). Last accessed 11 May 2021. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKLfz-VacvnnHxIqR5GMKtw?app=desktop.↩︎

During samāyik a householder temporarily becomes an ascetic, chanting mantras, listening to sermons, engaging in meditation or other suchlike practices.↩︎

On the growing popularity of Jain religious apps, see Vekemans (2019b).↩︎

This supports Vekemans’ hypothesis that “most temple-going Jains will in all probability argue that physical proximity to a consecrated idol in a dedicated temple space cannot be replicated fully online” (Vekemans 2021, 17).↩︎

See also Jain, Shugan (2020); Jain, Pragya and Sayyam Jain (2020); Sanchetee, Pratap and Prashant Sanchetee (2020).↩︎

See also “Framing the Pandemic,” where I show how some Jains during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic actively drew parallels between various WHO-guidelines and Jain tenets, and by doing so, present “Jainism as a practical, resourceful, and scientifically supported way of life” (Maes 2022, 2).↩︎

Also, various Jain ācāryas such as the late ācārya Gyansagar Mahārāj and ācārya Śivamuni explain the causes of the pandemic by reverting to the Jain theory of karma. See https://www.speakingtree.in/article/corona-karma (last accessed 30 June 2021) and Prajñā (2021, 7–8), respectively.↩︎

For a detailed description of Rahul Kapoor Jain’s work, see https://www.rahulkapoor.in/best-motivational-speaker-india.html (last accessed 8 April 2022).↩︎

Rahul Kapoor Jain’s Say No to More: A 3 Step Solution to Climate Change. Last accessed 17 May 2021. https://jainavenue.org/videos/.↩︎

Rahul Kapoor Jain’s Get Back into Your True Nature. Last accessed 16 May 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zS_K02l75k.↩︎

Think, for instance, of the above quoted statement of the online platform The Jain Foundation: “[Jainism is] a religion which today science is proving time and again to be accurate to the very last detail.” See https://www.jainfoundation.in/the_jain_foundation.php (last accessed 14 May 2021).↩︎

FIU Conference Website. Last accessed 4 March 2021. https://icsjp.fiu.edu/. It is worth noting that one of the organizers of the event, Samanī Chaitanya Prajñā, is a strong proponent of the universalization of Jainism.↩︎

This short biography of Rajmal Jain is based on a semi-structured Zoom interview I conducted with him on the topic of the scientization of Jainism on 1 February 2022.↩︎

Rajmal Jain’s article contains thus both specific and unspecific appeals to the authority of science. Specific, because his article is a scientific paper that seeks to show the relevance of applying Jain principles. Unspecific, because Rajmal Jain equally makes several claims that Jainism is scientific, without explaining why this is the case.↩︎