The Sogdians and Their Religions in Turfan: Evidence in the Catalogue of the Middle Iranian Fragments in Sogdian Script of the Berlin Turfan Collection

We are able to verify the variety of the religions of the Sogdians by the text fragments found in the Turfan oasis (East Turkistan, today’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region of China). They are housed in several libraries and museums in Europe, Japan, and China. The Berlin Turfan collection contains a large part of them. The catalogue of the Sogdian text fragments in the indigenous Sogdian script of that collection was completed in 2018. The fragments represent parts of the literature of Christian, Manichaean and Buddhist communities in Turfan from eighth to eleventh century CE. The best represented religion in the homeland of the Sogdians is a type of the Zoroastrian religion, as evidenced by archaeological findings and wall paintings. However, there are only very few texts found in Turfan and other locations in Central Asia which could be interpreted as Zoroastrian. The discussion about the religious affiliation of those texts is going on. The religious background of some other text fragments from Turfan is difficult to identify as well. Two of these examples will be published here. A remarkable feature of the religious communities in Turfan is the multilingual character of their literature, reflecting the development and path of the believers and the multi-ethnical structure of the community.

Sogdian, Manichaeism, Buddhism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, manuscripts

Introduction

This article gives a short survey of the religions of the Sogdians, a population which lived in Central Asia, speaking an Indo-European language known as Sogdian, which has come to our knowledge by several coins and numerous text materials from Central Asia as described below. The Sogdians were already known in Antiquity, as attested by Old Persian inscriptions, because of their gifts to the Achaemenid rulers, and by Chinese historiographers.

There is a difference between evidence for religions attested in the homeland of the Sogdians, so-called Sogdiana, and in the textual remains found along the Silk Road to China, mainly Turfan and Dunhuang 敦煌 and some graves in Ningxia 宁夏. Several European and Japanese expeditions excavated these materials at the beginning of the twentieth century. Afterwards, Chinese archaeological campaigns continued the archaeological work. This article is based mainly on the textual evidence found in the Turfan region by the four German expeditions undertaken between 1902 and 1914, and brought to Berlin. These materials are housed now in the so-called Berlin Turfan collection in the Museum of Asiatic art and in the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, curated by the Berlin State Library. The materials found in Dunhuang by French and British scholars like Paul Pelliot and Sir Aurel Stein are stored in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris and in the British Library in London. Important collections from Turfan and Dunhuang are preserved in the Oriental Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, in Ryukoku University in Kyoto and in several Chinese libraries.

Because of the fact that Sogdian played a role as lingua franca in the first millennium CE along the Silk Road, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the textual evidence produced by Sogdians themselves and those written by other people, mainly by Uyghurs. Eventually, Sogdian ceased to be widely spoken, and a form of New Persian replaced it throughout Sogdiana. The followers of the pre-Islamic religions had to migrate to regions further east and found refuge in the Central Asian oases. Most of the textual evidence originates from that time and offers a look into the religions of the Sogdians under conditions of adaptation and migration in the diaspora. Two manuscripts are edited at the end of the article to show the problems of identification of fragmentary texts. I thank Lilla Russell-Smith (Berlin) and Adam Benkato (Berkeley) for checking the English in my article. For all remaining mistakes I am responsible for myself.

Sogdians, Their Settlements, and Their Sources

Sogdiana

Sogdians are known from the middle of the first millennium BCE until the end of the first millennium CE. They lived in so-called Sogdiana, a clutch of cities in the area of what is today’s Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, along the Zarafshan and Kashka-darya rivers. The best known cities were Samarkand (archaeological area of Afrasiab), Bukhara, Paikend, and Penjikent. The Sogdians travelled as merchants through Central Asia to China and to the Upper Indus valleys in the first millennium CE. They settled in Taschkent (Čāč), Semirechie in Mongolia, the Turfan area and up to Xiʾan 西安 (Changan 長安). The archaeological findings in the Sogdiana area, documents from Mt. Mugh, text fragments from the Turfan and Dunhuang areas, and grave inscriptions from tombs in today’s Ningxia region up to Xiʾan give some insights into the history of the Sogdians and into their religions. The religion of the Sogdians in their homeland is described as a kind of “polis religion” similar to the situation in the Classical Greece (Shenkar 2017). Most characteristics of this religion can be deduced from paintings and other artistic artifacts (Mode 2003; Grenet 2015b), but the textual base is very thin. But theophoric components of the Sogdian names show a strong familiarity with Zoroastrian deities. The ossuaries and reliefs of grave chambers in China depict Zoroastrian rituals. They indicate that the native religion of the Sogdians in their homeland was a kind of Zoroastrianism which was also maintained in the diaspora, with possible interdependencies with Buddhism and Manichaeism. Some details in the reliefs allow different interpretations, and several elements are still under discussion (Gulácsi and BeDuhn 2012; opposed to De la Vaissière 2019). There are also traces of Christianity, Manichaeism, and Buddhism to be found in reports and a few archaeological findings (for example: Ashurov 2019). An-Nadīm (tenth century CE) reported on the Manichaean community in Samarkand, its history, the schism of the community, the teachings, and the rituals of the Manichaeans in his Kitāb al-fihrist (Dodge 1970, 773–805). This testimony is mostly reliable and that is why it is also useful for the research of the history of this religion. In particular, an-Nadīm reported on the schism of the community in Transoxania, which “denied the authority of the archegos (the Supreme Head of the Manichaean church) in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, Babylonia, and declared their religious independence” (Colditz 1994, 229), referring to this schismatic community as the Dīnāwarīya. The best-known head of the Dīnāwarīya was Šād Ohrmezd, d. 600-1 CE (Colditz 1992, 322–8, 1994; Lieu 1992, 220–30). The schism ended between 710 and 715, when the Dīnāwarīya recognised again the authority of Mihr, the archegos in Seleucia-Ctesiphon. Under the reign of al-Muqtadir (908–932 CE), approximately 500 Manichaeans fled again from Mesopotamia to Samarkand, as mentioned by An-Nadīm (Dodge 1970, 802; Reeves 2011, 228; Yoshida 2017a, 119–20). Thereafter the head of the Manicheans, their archegos, lived in Samarkand before the seat moved on to Turfan.

Turfan and Dunhuang

The text fragments found in Dunhuang and in the Turfan oasis (East Turkistan, today’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region of China) show a variety of religions among the Sogdians. As can be seen in the text fragments edited in several publications (Benveniste 1940; MacKenzie 1976; Ragoza 1980, with many additions and corrections by N. Sims-Williams and Y. Yoshida and others) and described in the catalogues, the three religions Buddhism, Christianity, and Manichaeism are all represented in the findings from Central Asia. It is thought that Sogdian merchants brought these religions to Central Asia. These texts were discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century and transferred to several libraries and museums in Europe, Japan, and China, with the Berlin Turfan collection containing the largest part. Research on these materials and the edition of it began in 1902, when the first materials of the excavations in Turfan were brought to Berlin, and has been continued up to the present time in the Turfan Research group of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities and by other scholars from all over the world. Coincidentally during the last decades, the work of cataloguing the Sogdian fragments went on, carried out by the staff of the project Union Catalogue of the Oriental Manuscripts of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities, and two other scholars. The catalogue of the Sogdian text fragments in the indigenous Sogdian script was completed in 2018 in three volumes (Reck 2006, 2016, 2018b). The catalogue of the Christian Sogdian fragments in Syriac script in the Berlin Turfan collection was published in 2012 by Nicholas Sims-Williams (2012). Enrico Morano is working on a publication about the Manichaean Sogdian fragments in Manichaean script as listed in the Catalogue of the Iranian Manichaean manuscripts in Manichaean script by Mary Boyce (Boyce 1960; Morano 2007). The completion of the cataloguing work on the Sogdian fragments in the Berlin Turfan Collection was the occasion to present this contribution. The catalogues are divided into several parts in accordance with their religious affiliation. The Sogdian texts from the Turfan region are written in three different scripts, first the indigenous Sogdian one, second in Manichaean script, used by the founder of the Manichaean religions himself in the third century for Manichaean literature and from that point for Manichaean texts in several languages, and third in East Syriac script (Sims-Williams 1989, 175–78; Gharib 1995, 29 (Persian); Reck 2014). The usage of Manichaean and the East Syriac script was exclusively connected with the religious affiliation of the texts. The indigenous Sogdian script was used for writing all kinds of religious texts and for letters and documents as well. Some of the texts are bilingual respectively composite manuscripts. Often Uyghur names, headlines and colophons in the manuscripts show the close relationship between the Sogdian and Uyghur members of the communities. On the one hand, Sogdian merchants contributed to circulating religions like Manichaeism and Christianity. On the other, Uyghur communities used Sogdian sources besides the church literature in other languages. Manichaeism, for example, was the state religion in the East Uyghur Khanat and in the West Uyghur kingdom of Kočo as well. The Uyghur court protected the Manichaean communities in the time of the eighth to tenth centuries.

A recently published new interpretation of the Judeo-Persian letters from Khotan by Yutaka Yoshida explains the existence of Sogdian words in this New Persian text with a Jewish merchant, speaking Sogdian and New Persian, who wrote these letters at the beginning of the Persianization of Sogdiana (Yoshida 2019b, 392). Nevertheless, there is no more evidence of Jewish texts in that area.

Because of the fragmentary state of the literature on the different religions and the pieces of text fragments itself, it is difficult to make definitive conclusions about the role of these religions among the Sogdians in the diaspora. There are preserved Sogdian texts of several religions, which means that religion could not serve as the only feature of identification. Even though there are differences between vocabulary, features of grammar, and orthography, one cannot deduce a kind of religious language typically only for one or the other religion. Nevertheless, there are at least two Christian dialects represented in the texts from Bulayık, a Western one, connected with the Sogdiana, and an Eastern one, connected with the Christian community of Semirech’e (Yoshida 1980, 2017a).

| Languages | Manichaean script | Sogdian script | East Syriac script | Brāhmī script |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sogdian | Manichaean texts | Buddhist, Christian, Manichaean, and Zoroastrian(?) texts | Christian texts | Buddhist, medical texts |

| Middle Persian | Manichaean texts | Transcription of Manichaean texts, mostly hymns | ||

| Parthian | Manichaean texts | Transcription of Manichaean texts, mostly hymns | ||

| Uyghur | Headlines, Bilinguals | Bilinguals, parts of texts, colophones, words, names | ||

| Chinese | Transcription of Buddhist texts | |||

| Syriac | Sogdian texts with Syriac rubrics | Bilingual, beginnings, Syriac texts with Sogdian rubrics, Sogdian texts, with Syriac rubrics |

Of course, the Manichaean, Buddhist, and Christian texts are written in other languages and scripts as well. A small amount of very fragmentary texts is written in Brāhmī script. Only a few of them have been identified as yet.

Sogdians and Their Religions Seen in Sogdian Sources

Buddhism

Although it is understood that Iranians (“Yuezhi,” i.e. Kuṣāṇa, maybe with the help of Sogdians, Tremblay 2007, 93–94) transferred Buddhist texts to Central Asia and China, where they were translated into Chinese, most of the texts found in Central Asia are later translations either from an unknown language or Tocharian, but mostly from Chinese versions. Therefore, one can conclude that in this case the Sogdian merchants came into contact with Buddhism in China and possibly used it to strengthen their commercial contacts. Yutaka Yoshida confirms Xavier Tremblay’s description of Sogdian Buddhism as a “colonial” one (Tremblay 2007, 95; apud Yoshida 2013a, 155). A recent representative overview about the Buddhist literature of the Sogdians is given by Yoshida (2009, 2015). At the same time and up to now he has published several important articles discussing single items of the Buddhist Sogdian texts and editing matching fragments. He is studying the representation of the different Buddhist schools which appear in the Buddhist Sogdian texts. Scholars initially assumed that the Sogdians followed the Mahāyāna school because the first texts analysed were translations of Chinese Mahāyāna texts. The school of Mahāyāna, which means “large vehicle,” teaches that all people can reach the Buddhahood, in contrast to the early Buddhist school of Theravāda, which teaches that only a very strict monastic life can lead to the arhatship of single monks. Yoshida found evidence of Vinaya texts of the Theravāda school and, most recently, parts of texts which “seem to have been produced in the cultural context of the (Mūla)sarvāstivādin school” (2019a, 159). These texts are not translated from Chinese texts but relate to Tocharian and Uyghur versions. The bulk of the extant texts are nevertheless parts of various kinds of Mahāyāna texts related to several directions of thought like Madhyamaka, Amitābha, Chan (known today as Zen Buddhism) and some kinds of esoteric Buddhism (Yoshida 2018, 2020b, 196–200). It would go too far to explain these different Buddhist schools here in detail. Important is the fact that these few Buddhist Sogdian text fragments preserved in the Turfan area represent a wide range of the Buddhist communities of the area and time among the Sogdians as well as they come down to us via the Buddhist texts in Chinese, Sanskrit, Tocharian, Saka, Uyghur, and other languages. Recent excavations brought to light some evidence for Buddhism among Sogdians also in Semirech’e, Kyrgyzstan, in the archaeological site of Ak-Beshim, which should be established later than Xuanzang’s visit there in 630 AD. It is not clear what the nature of this Buddhism is, possibly a kind of mixed esoteric Buddhism of Indian origin, as suggested by a statue of Avalokiteśvara (Yoshida 2020b, 201).

Christianity

Traces of the Christian Syriac “Church of the East,” in former times also known as “Nestorian church,” were found in several places in Central Asia as grave inscriptions, wall paintings, and text fragments. The bulk of the Christian Sogdian texts was found on the second Turfan expedition at a place called Bulayık in the north of Turfan; a small number were found in the Dunhuang area (Ashurov 2015, 4). The fragments from the Turfan area in many cases are labelled by so-called finding signatures/sigles. They use T for Turfan, followed by the number of the German expedition mentioned above: I – IV. Afterwards the location or ruin is mentioned, in this case B for Bulayık. Often, the number of the package in which the fragment was sent to Berlin is also mentioned. So the Christian fragments mostly are signed with the finding sigle T II B, some of them T III T.V.B., which means that they were found during the third expedition at “Turfaner Vorberge” (the hills near Turfan), another description of the same place. A few fragments were excavated in several other places of the Turfan oasis as well and represent evidence of other and presumably earlier Christian communities, as that of Bulayık (Yoshida 2017a, 156–58; Zieme 2015, 14–15). The Christian community from Bulayık kept and produced texts in Syriac, Sogdian, Uyghur, and in New Persian as well. Most of these texts are written in Syriac script, but some are in Sogdo-Uyghur script as well. From the Old Testament only parts of the psalms are preserved. They are also transcribed into Sogdian script in two manuscripts. One of these manuscripts contains not only psalms but the creed and another hymn in service often used as well (Sims-Williams 2014, 32:7–53, with Martin Schwartz). The other manuscript is characterised by Greek quotations of the beginnings of each psalm in the upper margin (Sims-Williams 2004, 2011). Parts of Sogdian translations of the New Testament are preserved. They are based on the Syriac Peshitta version (Sims-Williams 2009, 275–76). The other Sogdian texts in Syriac script are mostly lectionaries, hagiographical literature, texts referring to monastic life, and some anti-Manichaica (Sims-Williams 2009, 279–83). Although the Manichaeans are not mentioned directly, the contents make clear that it is about Manichaeism because of the discussion about dualism (two eternal beings) and the mention of the two classes of adherents, Electi and Hearers. Another anti-Manichaean text fragment refers to the doctrine of transmigration. A third very defective passage mentions praying to idols (Sims-Williams 2009, 283–87, 2019145–54).

In addition to the catalogues of the Sogdian Christian fragments mentioned above, the catalogue of the Syriac fragments and the most recent edition of a Syriac Service-Book is an important milestone of the research on this part of the Christian texts from Central Asia (Hunter and Dickens 2015; Hunter and Coakley 2017). Syriac was the ecclesiastical language of the Christian church in the Turfan area, whereas the community was Sogdian or Uyghur speaking. The Old Uyghur Christian texts from Turfan have been published and partly re-edited by Peter Zieme. They are preserved in Syriac and in Uyghur script as well (Zieme 2015). There is a close relation between the Sogdian and Uyghur Christians in Turfan (Sims-Williams 1992).

Manichaeism

The most important findings in Central Asia are the Manichaean manuscripts, unearthed in the Turfan oasis by Russian, German, and Japanese expeditions. These were the first original remnants of this extinct religion, which spread in the first millennium CE from the Roman Empire up to Central Asia, to have been discovered. Recent evidence has also been found in China in the province Fujian 福建. Manichaeism was brought to China by the Sogdian merchants at the end of the seventh century (Lieu 1992, 230). There had already been small communities along the Silk Road, like Argi, mentioned in an extensive colophon to the hymn-book Mahrnāmag, which has been initiated there in the year 762 AD (Lieu 1992, 229; Müller 1913, 15–16; Henning 1937a, 566 [594] with Fn. 1). The Manichaean religion itself was predestinated for ruling circles and merchants because of its rejection of agricultural work and other crafts, which are held to torture the light soul imprisoned in living beings like plants and animals (Lieu 1992, 98; Durkin-Meisterernst 2015, 252–53). The pre-existing Sogdian network of merchants was surely used by monks for the Manichaean mission, and the merchants themselves played an active role in the diffusion of Manicheism (Sundermann 1995). Possibly they also assimilated as necessary to the situation they found in the locations along their routes. In the East Uyghur Khanate, and afterwards in the West Uyghur Kingdom in the Turfan area, Manichaeism was the state religion and enjoyed the protection of the Uyghur court. In this way the Turfan area became one of the 12 regions where a “Teacher” (mōžak) resided, this being the second highest rank among the Manichaean communities in the world after the “Archegos” (MP pašaγrīw) (Leurini 2004). Mani, the founder of this religion, who lived in the third century CE in Mesopotamia and in the Sasanian Empire, had himself implemented the hierarchical structure of his church. It is basically divided in clerical “Electi” and lay “Hearers,” as mentioned above. Most of the Electi served in the church as monks of minor orders. They were headed by 360 administrators (mānsārārān), who themselves were instructed by 72 bishops (aftādān). The Manichaean church was departmentalized into 12 regions worldwide, each directed by a “Teacher” (mōžak), who was mentioned in the Manichaean literature in the Turfan area. It may emphasize the high importance of the Manichaean community in the Turfan area. Most of the fragments of Manichaean literature, often decorated with fine miniatures, was found in temples of Qočo (Gaochang, near Turfan), where one of the capitals in the West Uyghur Kingdom was located (Moriyasu 2004, 155). In the early tenth century CE many Manichaeans left Mesopotamia for Samarkand because of the persecutions by al-Muqtadir. As established recently by Yutaka Yoshida, the center of the Manichaean community was situated in Turfan at that time. Now the “Archegos,” the person of the highest rank in the Manichaean community, resided in Turfan (Yoshida 2017b, 124). The Sogdian letters found in Turfan, published by Werner Sundermann and Yutaka Yoshida, attest to this fact (Sundermann 2007; Yoshida 2017b, 125, 2019c, 43–45). The Manichaean literature of the Turfan area is written in several languages, Middle Persian and Parthian as church languages, Sogdian and Old Uyghur as languages of the communities, and some in New Persian and Tocharian. The Sogdian language played an important role because of the relationship between the Manichaean communities in Samarkand and in the Turfan area, the activities of the Sogdian merchants as distributors of the religion, and the usage of Sogdian as literary language of the Old Uyghurs before they used the Sogdian script for their own texts. Manichaean Sogdian texts were written in Manichaean and Sogdian script as well. The fragments from Turfan preserve translations of Mani’s own scripts, hagiographical texts, didactical texts, homilies and sermons, parables, confessional texts, hymns, magical texts, letters, and a few documents. Many of them were parts of miscellanies, collecting texts of different genres respectively texts in different languages. The parts of Mani’s writings are translations of course. Some others like the confessional “Xwāstwānīft” are translations from Parthian, like the Parthian title “Xwāstwānīft” (confession) shows, or from Middle Persian. Some of the didactical texts or tales can be products of the Sogdian communities. There are only very few Sogdian poetical products (Provasi 2009, 347–8; Morano 2017). Mostly, Parthian and Middle Persian hymns were transcribed into Sogdian script to be legible for people who were not able to read the Manichaean script (Reck 2010).

Among the findings from Dunhuang, only very few texts could be identified as Manichaean. The most important findings were the Chinese Manichaean texts, housed in London and Paris: the Manichaean hymn scroll, Compendium, and the Traité (Tremblay 2001, 239–40). These texts are important for the Manichaeology because of their volume, good state of preservation, and many details they refer to. They help in the completion of the fragmentary texts in the Middle Iranian fragments, including the Sogdian ones and for comparison of details in the transmission. There are also some Sogdian Manichaean texts from Turfan and Dunhuang in Chinese libraries in the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, in the Ōtani collection in Kyōtō, in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, and in the British Library of London (for example, Sims-Williams 1976, 48–51; Yoshida 2019c, 179–80). There are many articles by Nicholas Sims-Williams, Yutaka Yoshida, Elio Provasi and others about the fragments in the several collections.

The Question Regarding Zoroastrianism

Contrary to the clear evidence for a special kind of Zoroastrianism in the Sogdiana, the findings in Dunhuang, Turfan are not clearly identifiable (Grenet and Azarnouche 2007; Shenkar 2017; Yoshida 2020a). There were some graves unearthed in China which brought to light well-preserved couches with reliefs which show interesting details of the daily life of the Sogdians. Among them scenes of fire altars are visible (Jiang 2000; Grenet, Riboud, and Junkai 2004). Therefore, Zoroastrianism could be identified also in the diaspora. But as it has been shown, the written sources excavated in the Turfan area demonstrate the presence of other religions. That is why it is under discussion whether Manichaean elements could be discovered in these funerary couch reliefs as well. Zsuzsanna Gulácsi and Jason BeDuhn disproved the first Manichaean identifications, and stress the clear Zoroastrian (in a broader sense) character of the representations of death and afterlife in the reliefs (Gulácsi and BeDuhn 2012). Étienne de la Vaissière identified, in a more recent article, topics like Mani as Maitreya stopping hunting, the lifting of the deceased out of the tossing sea, the three gifts and the judgment scene. He interprets this as a “testimony of a Zoroastrianism of an earlier period, while reflecting the florescence of Manichaeism in sixth century Sogdiana” (De la Vaissière 2005, 2015, 2019, 75). The burial practice of stone couches in China fulfilled the Zoroastrian precept that did not permit bringing corpses into earth, water and fire; neither was it possible to present the corpses in towers of silence. The bilingual epitaphs found at several places in China also give a hint at that solution. They mention the passage kʾw sʾcy wyʾʾk(kh) “in a suitable place” for the corpses (Yoshida 2005, 32, l. 32; Bi, Sims-Williams, and Yan 2017, 312, l. 15). This is to be interpreted that the corpses are buried in accordance with the Zoroastrian instructions.

But what about the Sogdian texts from Turfan and Dunhuang? Zarathuštra was held to be one of the prophet predecessors of Mani in the Manichaean doctrine. A description of his life was found in some fragments published by Werner Sundermann (1986). Zoroastrian vocabulary and nomenclature are used in the Manichaean myth propagated in the Sasanian Empire and spread through Central Asia (Hutter 2015). So another Manichaean text, the so-called Zarathuštra fragment, published by Walter B. Henning, uses the person of Zarathuštra as a representative apostle in the dialogue with his soul to explain the myth (Henning 1934, 27 [872]). But these are no Zoroastrian materials, but Manichaean ones. There are some other Sogdian texts which are more closely connected with Zoroastrianism itself. The best known is the fragment from Dunhuang, housed in the British Library, Or. 8212/84 (Ch. 00289) and including the Old Sogdian version of the central Zoroastrian prayer Ašəm vohū (Sims-Williams 1976, 46–48 (Frag. 4) with the Appendix by I. Gershevitch, 75–82). This prayer is very important in Zoroastrianism as it contains the praise of Truth. It concludes many longer prayers like a meditation formula. In this fragment it is continued by the so-called Fragment Japan 1, published by Yutaka Yoshida in 1979 as a Manichaean fragment for philological reasons (1979, 187). In contrast, Frantz Grenet and Samra Azarnouche counted the texts together with the often discussed text P3 closely connected with the sacred scriptures of the Zoroastrians (Benveniste 1940, 3:59–73; Grenet and Azarnouche 2007, 170–73). Also Nicholas Sims-Williams described the fragment of the British Library as a “rare example of Zoroastrian literature in Sogdian” (Sims-Williams apud Whitfield and Sims-Williams 2004, 118). Another fragment of the British Library, Or. 8212/81 (Ch. 00349), written in the same distinctive handwriting, contains an episode about Rustam, one of the most important heroes of the Šāhnāma, the “Book of the Kings.” Although the episode itself does not occur in the Šāhnāma, the Persian words in this text let us assume that the text was translated or adapted from a Middle Persian or New Persian original now lost (Sims-Williams 1976, 54–61, Frag. 13; Sims-Williams apud Whitfield and Sims-Williams 2004, 119; Grenet 2015a, 423). Yutaka Yoshida edited a fragment of the Lushun 旅順-collection, LM20: 1480/22(02) (Yoshida 2013b). This collection is a section of the findings of the Otani expeditions, housed in Lushun Museum in China. This fragment contains Sogdian text with almost complete lines which mentions a lot of names of heroes of the Šāhnāma and shows that the Sogdians did not know only Rustam but also other stories of the Šāhnāma. This is also proved by the Sogdian names taken from Iranian folklore for figures in the Manichaean Book of Giants, like Narīmān and Sāhm (Colditz 2018, 402 # 378; Lurje 2010, 342 # 1068). The currently unresolved question is whether these manuscripts were literary products, or remnants of a Zoroastrian literature, or parts of the Manichaean literature using Zoroastrian or pagan literary passages. We should not underestimate the oral transfer of Zoroastrian rituals and texts. In addition, one cannot expect a closed, strongly codified Zoroastrianism in the diaspora, as already described above. Finally, among the Turfan manuscripts there is also a fragment with a list of grammatical forms of Middle Persian verbs in heterographic writing in Pahlavi script (Geldner 1904; Barr 1936). It is only a single fragment and must not be overestimated. But it shows that supporting material for the reading of Zoroastrian Pahlavi literature also existed in Turfan, which was not ‘normal’ travel reading for merchants, but may have been teaching material for scribes (Barr 1936, 396).

Manuscripts of Uncertain Affiliation

There are also some manuscripts in the Berlin Turfan collection which contain text which could not be identified with certainty as Manichaean, Buddhist, or Christian, described in the third part of the catalogue (Reck 2018b, 18 (3):71–139). The problem has already been discussed in several places (Reck 2018a, and Reck forthcoming). Although it would be most likely that they belong to one of the well-known groups of religious fragments, a small probability remains that they could represent parts of Zoroastrian literature. Unfortunately, most of these uncertain fragments are very small and lack relevant names or items which would allow ascertaining the religious affiliation. Neither do they show formal peculiarities, which can be observed as characteristics for the literature of the several religious groups. That is the reason why such fragments will usually not be published in any way. But they are part of a limited corpus of texts, where every attestation of words is significant for further research and should be discussed. This is the first publication of these small fragments So 16102(2) and So 16146. Both are written in a distinctive kind of the cursive Sogdian script from the same hand. It is not possible to join the fragments to get a more complete text. They contain passages which can be interpreted in several directions. That is why the religious affiliation of these text fragments is not clear. In this way they point out the difficulty of determining a religion of the Sogdians in the Turfan area.

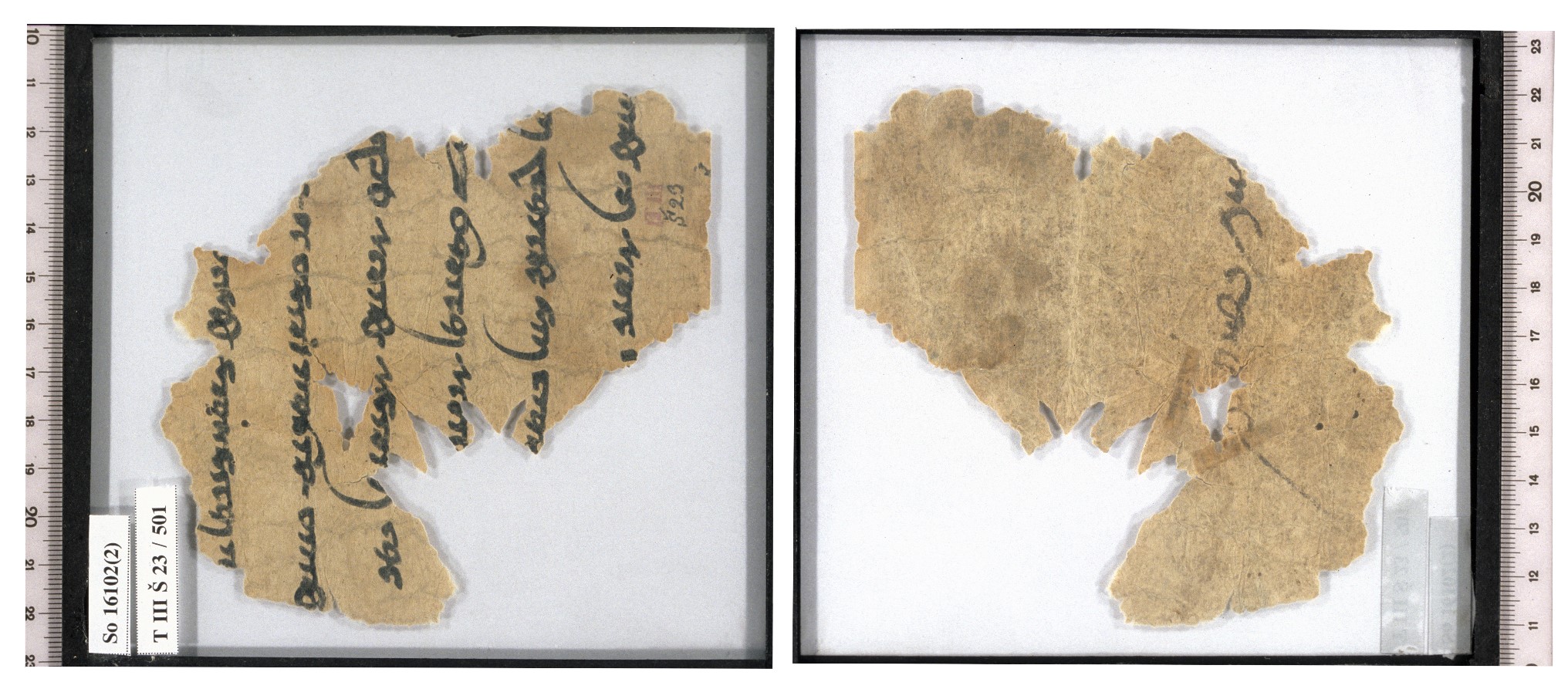

The fragment So 16102(2), T III Š 23/501 (Reck 2018b, 18 (3):93, nr. 1048) has a size of 11.1 x 11.5 cm. On the recto side there are six incomplete lines, on the verso side the end of one line in another script (Fig. 1).

| r/1/ | ](w)yspw mrtxmʾyt ʾ(.)[ | ] all men [ |

| /2/ | ](m) ZY wmʾrẓ-ʾntkʾm ʾnʾkw[ | ] and they will destroy, that [ |

| /3/ | n](y)δcw šyrʾkw šmʾrn(t) rty | ] they do not think anything good. And [ |

| /4/ | ](h) ptrʾy-t šyrʾ(y)[ | ] the fathers good[ |

| /5/ | ](n) δβtʾyky sʾn βnt(k)[ʾm | ] another enemy [will] be bound[ |

| /6/ | w/c](ʾ)nʾkw ZK šyrʾy ZY (.)[ | ]as the good and [ |

| v/1/ | ](.)n/zm ywγt[y]m | ]… I have learned |

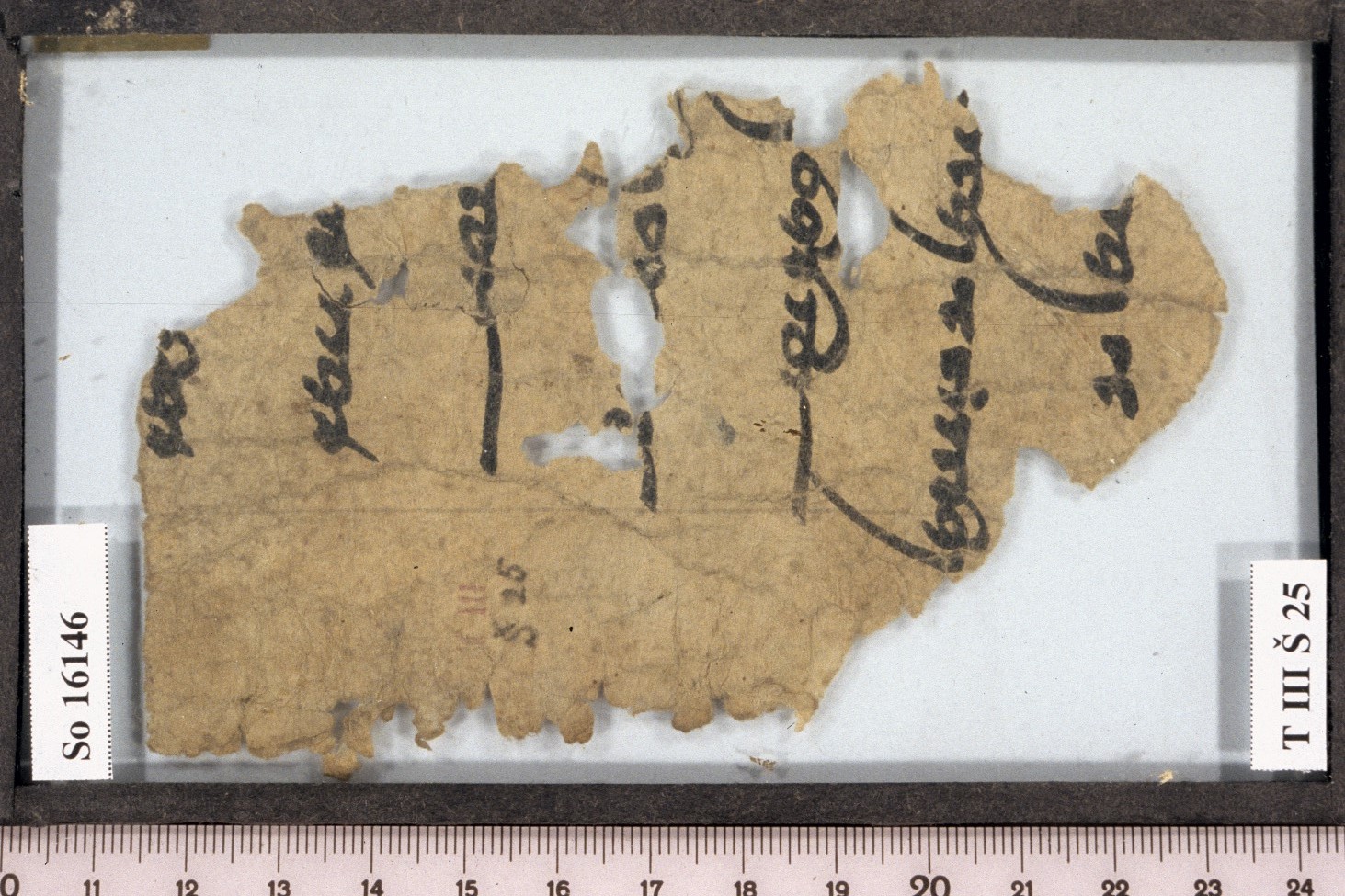

The fragment So 16146, T III Š 25 (Reck 2018b, 18 (3):95, nr. 1050) has a size of 7.7 x 11.8 cm. On the recto side there are the ends of seven lines (Fig. 2), the verso side is blank.

| r/1/ | ](k)rtr | ]cunning/large mass |

| /2/ | ](.)w ʾʾtr | ]… fire |

| /3/ | ]ywn | ]… |

| /4/ | ](p/k)t w(.)[3–4](w) | ]… |

| /5/ | ](.) ptkʾwn | ] upside down/heretic |

| /6/ | ](.)ʾyt ZY βẓʾykt | ]… and evil |

| /7/ | ](.)t ZY | ] … and |

There is no context, nor special terms or names, which could allow a distinction of the religious affiliation of these texts. The words on the verso side of So 16102(2) reminds one of the colophons of Manichaean books, edited and explained by Yutaka Yoshida: ʿyny pwstk/ywkh ʾz-w … ywγtym, ky Lʾ pyrʾt … sʾr psδ/tʾ “This book/teaching I, […], have learned, who would not believe it, ask […]” (Yoshida 2000, 83–85; Benkato 2017, 107–11). If there were a relation between the text on the recto side and the colophon on the verso side, the text on the recto could be Manichaean. But there are some Buddhist fragments written in the same hand which contain remnants of this colophon as well (So 10100u, So 10650(21) and So 18285, see Reck 2016, 18 (2):43, nr. 474, 95, nr. 552, and So 18285, nr. 822). Because of that and of the fact that most of the texts found in Šorcuq during the third expedition (finding sigle T III Š) are Buddhist, these fragments could be Buddhist as well. The mentioning of ʾʾtr “fire,” šyrʾy/šyrʾkw “good,” and βẓʾykt “evil” could be interpreted as Zoroastrian as well. But the word ptrʾy-t “fathers” would not be used in Zoroastrian for a higher ranking person, like a teacher (xwyšt(ʾ)k) (personal information by Kianoosh Rezania). So we cannot propose a Zoroastrian background for these fragments either. Neither was it possible to clarify whether they could be Buddhist or Manichaean. We are looking for other texts to compare for better interpretation, which is necessary for each single text fragment of this corpus.

Multilingualism

The Sogdian religious literature from Turfan and Dunhuang was marked by a multilingualism which is based on the offspring of the religions represented in it and in the diversity of the population. The church languages of the Eastern expansion of Manichaeans were Middle Persian and Parthian, the languages of the missionary activities. Mani’s Aramaic works had been translated mostly into Middle Persian, others by the missionaries, like Mār Ammō, into Parthian. Only one Syriac Manichaean fragment (M 260/r/6–12) with ends of lines, completed by means of transcriptions in the Chinese Hymns Scroll by Yutaka Yoshida (Yoshida 1983; see Pedersen and Larsen 2013, 1:3, 125 fn. 79, 126), is preserved in the Berlin Turfan collection (Durkin-Meisterernst 2006). There are preserved parts of translations of Mani’s works among the Turfan fragments, like the “Living Gospel” (translated into MP and bilingual into Sogdian as well, see Müller 1904, 25–27, 100–104; MacKenzie 1994; Shokri-Foumeshi 2015), the “Book of Giants” (translated into MP, Sogdian and Parthian, see Henning and B. 1943; Sundermann 2001; Morano 2016; there are some fragments of translations into Old Uyghur, see Wilkens 2000, 173–77, nr. 164–168), the “Psalms” (translated into MP, Sogdian and Parthian, see Durkin-Meisterernst and Morano 2010; Iain Gardner detected the accordance of a Greek prayer with quotations of the daily prayers in the Fihrist by An-Nadīm and in the Middle Iranian psalms; see Gardner 2011), and part of the so-called “Letter of the Seal” (translated into MP and Sogdian, see Henning 1937b; Reck 2009). Possibly the Middle Persian cycle “The Speech of the Living Soul” was composed by Mani as well. Some fragments also preserve Sogdian translations of this cycle. Most of the Parthian sermons were translated into Sogdian and Old Uyghur as well. It shows the importance of these works for the didactic purposes among the Sogdian and Uyghur communities. The hymns are mostly Parthian. They have not been translated into Sogdian but transcribed into the Sogdian script, so that people who were not able to read the Manichaean script anymore, could nevertheless read the hymns. Therefore, we have some Sogdian literary products in Manichaean and in Sogdian script as well (Henning and B. 1945, 465–69). Preserved fragments of bifolios or folios written in one hand belong mostly to miscellanies collecting parts of various works or hymns in various languages. Often the language of the headlines or liturgical advices differs from the following text. These liturgical advices are often Sogdian, which traces back to the Manichaean church in the Sogdiana preserved in the Uyghur community in Turfan as well. The material shows a close relationship to the Old Uyghur literature of that area. Further research would require a closer cooperation of specialists in the fields of Middle Iranian and Old Uyghur studies. The Christian material is multilingual as well: Syriac by origin, translated into Sogdian and Old Uyghur for liturgical and didactic purposes. The community in Turfan seemed to be dominantly Uyghur, as seen by the names and the documents.

The Buddhist texts are written only in the Sogdian language and Sogdian script. But the colophons mostly list Old Uyghur names or Sogdian and Uyghur names side by side. So the question of who wrote these texts, Uyghurs or Sogdians, cannot be answered with certainty. Linguistic arguments lead Yutaka Yoshida, in accordance with Nicholas Sims-Williams, to conclude that Turkicised Sogdophones wrote the Sogdian Turfan materials rather than Sogdianised Turcophones (2012, 57–58).

Conclusion

The article shows the different religions followed by Sogdians in their homeland and in the diaspora as well. Sogdian merchants brought Manichaeism along the Silk Road from Samarkand to Central Asia. In Turfan these religions flourished among the Uyghurs who used the Sogdian language and script. So the written sources show an amalgamation of Sogdian and Old Uyghur. The same happened with the small Christian communities. The texts attest a strong influence by the Sogdians and a continuation by the Uyghurs.

In contrast, the Sogdians came into contact with Buddhism in China only and traded it eastwards in Turfan and Dunhuang. The text fragments do not belong to a special Buddhist school but represent a considerable variety.

The special kind of Zoroastrianism in the Sogdiana cannot be seen in the same way in the diaspora. But there are traces of Zoroastrianism and Old Iranian culture to be observed in archaeological and literary remnants. In the diaspora one can assume several forms of mutual interference. The details are still in discussion.

Thus at the end one cannot establish a single religion as identifying factor for Sogdians. Sogdians were inspired by several religious communities and practices they came into contact with and carried it along their commercial routes. Eventually, Sogdians merged with other social and religious communities and ceased to appear in historical sources.

Image Rights

Images courtesy of “Depositum der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preussischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.”

References

Ashurov, Barakatullo. 2015. “Sogdian Christian Texts: The Manifestation of ‘Sogdian Christianity’.” Manuscripta Orientalia 21 (1): 3–17.

———. 2019. “’Sogdian Christianity’: Evidence from Architecture and Material Culture.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 29: 127–68.

Barr, Kaj. 1936. “Remarks on the Pahlavi Ligatures ….” BSOS, Indian and Iranian Studies, presented to George Abraham Grierson on his Eighty-Fifth Birthday, 8 (2-3): 391–403.

Benkato, Adam. 2017. Āzandnāmē: An Edition and Literary-Critical Study of the Manichaean-Sogdian Parable-Book. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

Benveniste, Emile. 1940. Codices Sogdiani: Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Nationale (Mission Pelliot). Reproduits en fac-similé avec un introduction par E. Benveniste. Vol. 3. Monumenta Linguarum Asiæ Maioris. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard.

Bi, Bo, Nicholas Sims-Williams, and Yan Yan. 2017. “Another Sogdian-Chinese Bilingual Epitaph.” BSOAS 89 (2): 305–18.

Boyce, Mary. 1960. Catalogue of the Iranian Manuscripts in Manichean Script in the German Turfan Collection. Veröffentlichung Des Instituts Für Orientforschung Der Deutschen Akademie Der Wissenschaften Zu Berlin 45. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Colditz, Iris. 1992. “Hymnen an Šād-Ohrmezd: Ein Beitrag zur frühen Geschichte der Dīnāwarīya in Transoxanien.” Altorientalische Forschungen 19 (2): 322–41.

———. 1994. “Shād Ohrmezd and the Early History of the Manichaean Dīnāwarīya-Community.” In Bamberger Zentralasienstudien: Konferenzakten ESCAS IV, Bamberg, 8. –12. Oktober 1991, edited by Ingeborg Baldauf and Michael Friederich, IV, Bamberg, 8:229–34. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag.

———. 2018. “Namen in manichäischer Überlieferung.” In Mitteliranische Namen. Vols. 2, Fasc. 1. Iranisches Personennamenbuch. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie Wissenschaften.

De la Vaissière, Étienne. 2005. “Mani En Chine Au VIe Siècle.” Journal Asiatique 293: 357–78.

———. 2015. “Wirkak: Manichaean, Zoroastrian, Khurrami?” Studies on the Inner Asian Languages, 95–112.

———. 2019. “The Faith of Wirkak the Dēnāwar, or Manichaeism as Seen from a Zoroastrian Point of View.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 29: 69–78.

Dodge, Bayard. 1970. The Fihrist of Al-Nadīm: A Tenth-Century Survey of Muslim Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

Durkin-Meisterernst, Desmond. 2006. “Aramaic in the Manichaean Turfan Texts.” In Iranian Languages and Texts from Iran and Turan: Ronald E. Emmerick Memorial Volume, edited by Maria Macuch, Mauro Maggi, and Werner Sundermann, 59–74. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

———. 2015. “Was Manichaeism A Merchant Religion?” In Journal of Turfan Studies: Essays on Ancient Coins and Silk: Selected Papers of the Fourth International Conference on Turfan Studies, edited by Academia Turfanica and Turfan Museum, edited by Academia Turfanica and Turfan Museum, 245–56. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji chubanshe.

Durkin-Meisterernst, Desmond, and Enrico Morano. 2010. Mani’s Psalms: Middle Persian, Parthian and Sogdian Texts in the Turfan Collection. Vol. 27. Berliner Turfantexte. Turnhout: Brepols.

Gardner, Iain. 2011. “’With a Pure Heart and a Truthful Tongue’: The Recovery of the Text of the Manichean Daily Prayers.” Journal of Late Antiquity 4 (1): 79–99.

Geldner, Karl Friedrich. 1904. “Bruchstück eines Pehlevi-Glossars aus Turfan, Chinesisch-Turkestan.” Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1136–7.

Gharib, Badri. 1995. Sogdian dictionary: Sogdian-Persian-English. Tehran: Farhangan Publications.

Grenet, Frantz. 2015a. “Between Written Texts, Oral Performances and Mural Paintings: Illustrated Scrolls in Pre-Islamic Central Asia.” In Orality and Textuality in the Iranian World: Patterns of Interaction Across the Centuries, edited by Julia Rubanovich, 422–45. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

———. 2015b. “The Sogdian Pantheon.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism, edited by Michael Stausberg, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina, and Anna Tessmann, 129–46. Wiley Blackwell.

Grenet, Frantz, and Samra Azarnouche. 2007. “Where Are the Sogdian Magi?” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 21: 159–77.

Grenet, Frantz, Pénélope Riboud, and Yang Junkai. 2004. “Zoroastrian Scenes on a Newly Discovered Sogdian Tomb in Xi’an, Northern China.” Studia Iranica 33 (2): 273–84.

Gulácsi, Zsuzsanna, and Jason BeDuhn. 2012. “The Religion of Wirkak and Wiyusi: The Zoroastrian Iconographic Program on a Sogdian Sarcophagus from Sixth-Century Xi’an.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 26: 1–32.

Henning, Walter. 1934. “Mitteliranische Manichaica aus Chinesisch-Turkestan III.” Edited by Phil-hist Kl SbPAW. SbPAW Phil.-hist. Kl.: 846–912.

———. 1937a. “Argi and the Tocharians.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 9: 545–71.

———. 1937b. “Ein manichäisches Bet- und Beichtbuch.” Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1: 417–557.

Henning, Walter, and B. 1943. “The Book of the Giants.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 11 (1): 52–74.

———. 1945. “Sogdian Tales.” BSOS 11 (3): 465–87.

Hunter, Erica, and John F. Coakley. 2017. A Syriac Service-Book from Turfan: Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin MS MIK III 45. Vol. 39. Berliner Turfantexte. Turnhout: Brepols.

Hunter, Erica, and Mark Dickens. 2015. Syrische Handschriften, Teil 2: Texte der Berliner Turfansammlung. Syriac Texts from the Berlin Turfan Collection. Vols. 5, 2. Verzeichnis der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Hutter, Manfred. 2015. “Manichaeism in Iran.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism, edited by Michael Stausberg, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw Vevaina, and Anna Tessmann, 477–89. Wiley Blackwell.

Jiang, Boqin. 2000. “The Zoroastrian Art of the Sogdians in China.” Edited by Bruce Doar and Bruce Doar. China Archaeology and Art Digest, Zoroastrianism in China, 4 (1): 35–71.

Leurini, Claudia. 2004. “Pasāgrīw – ‘Thronfolger’ Manis.” In Turfan Revisited: The First Century of Research into the Arts and Cultures of the Silk Road, edited by Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst, Simone-Christiane Raschmann, Jens Wilkens, Marianne Yaldiz, and Peter Zieme, 159–62. Berlin: Dietrich-Reimer-Verlag.

Lieu, Samuel N. C. 1992. Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China. 2nd ed. Tübingen: Mohr.

Lurje, Pavel. 2010. “Personal Names in Sogdian Texts.” In Mitteliranische Personennamen, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Vols. 2, Fasc. 8. Iranisches Personennamenbuch. Wien.

MacKenzie, David N. 1976. The Buddhist Sogdian Texts of the British Library. Edited by David N. MacKenzie. Vol. 10. Acta Iranica. Leiden/Teheran: Brill.

———. 1994. “’I Mani …’.” In Gnosisforschung Und Religionsgeschichte. Festschrift Für Kurt Rudolph Zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Holger Preissler, 183–98. Marburg: Diagonal-Verlag.

Mode, Markus. 2003. “Die Religion der Sogder im Spiegel ihrer Kunst.” In Die vorislamischen Religionen Mittelasiens, edited by Karl Jettmar and Ellen Kattner, 141–218. Die Religionen der Menschheit, 4 (3). Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

Morano, Enrico. 2007. “A Working Catalogue of the Berlin Sogdian Fragments in Manichaean Script.” Edited by Maria Macuch and Mauro Maggi. Iranian Languages and Texts from Iran and Turan: Ronald E. Emmerick Memorial Volume, Iranica, 13: 23–70.

———. 2016. “Some New Sogdian Fragments Related to Mani’s Book of Giants and the Problem of the Influence of Jewish Enochic Literature.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck, and Enrico Morano, 187–98. Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck.

———. 2017. “Some New Sogdian Fragments Related to Mani’s Book of Giants and the Problem of the Influence of Jewish Enochic Literature.” In Manichaeism East and West, edited by Samuel N. C. Lieu, Erica Hunter, Enrico Morano, and Nils Arne Pedersen. Corpus Fontium Manichaeorum: Analecta Manichaica 1. Tunhout: Brepols.

Moriyasu, Takao. 2004. Die Geschichte des uigurischen Manichäismus an der Seidenstraße: Forschungen zu manichäischen Quellen und ihrem geschichtlichen Hintergrund. Translated by Christian Steineck. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Müller, Friedrich W. 1904. Handschriften-Reste in Estrangelo-Schrift aus Turfan, Chinesisch-Turkistan: II. Teil. APAW. Berlin.

———. 1913. Ein Doppelblatt aus einem Manichäischen Hymnenbuch (Maḥrnāmag). APAW. Berlin.

Pedersen, Nils Arne, and John Møller Larsen. 2013. Manichaean Texts in Syriac: First Editions, New Editions, and Studies, Corpus Fontium Manichaeorum. Vol. 1. Series Syriaca. Turnhout: Brepols.

Provasi, Elio. 2009. “Versification in Sogdian.” In Exegisti monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams, edited by Almut Hintze, Werner Sundermann, and François de Blois, 347–68. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Ragoza, A. N. 1980. Sogdijskie Fragmenty: Central’no Aziatskogo Sobranija Instituta Vostokovedenija: Faksimile. Izdanie Tekstov, čtenie, Perevod, Predislovie, Primečanija I Glossarij. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Nauka.

Reck, Christiane. 2006. Mitteliranische Handschriften, Teil 1: Berliner Turfanfragmente manichäischen Inhalts in soghdischer Schrift. Vol. 18 (1). VOHD. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

———. 2009. “A Sogdian Version of Mani’s Letter of the Seal.” In New Light on Manichaeism: Papers from the Sixth International Congress on Manichaeism, edited by Jason D. BeDuhn, 225–39. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

———. 2010. “Some Remarks on the Manichaean Fragments in Sogdian Script in the Berlin Turfan Collection.” In The Way of Buddha 2003: The 100th Anniversary of the Otani Mission and the 50th of the Research Society for Central Asian Cultures, edited by T. Irisawa, 69–74. Cultures of the Silk Road and Modern Science 1. Kyoto: Ryukoku University.

———. 2014. “The Middle Iranian Manuscripts from the Berlin Turfan Collection: Diverstiy, Origin and Reuse.” In Lecteurs et Copistes Dans Les Traditions Manuscrits Iraniennes, Indiennes et Centrasiatiques ̶ Scribes and Readers in Iranian, Indian and Central Asian Manuscript Traditions, edited by Nalini Balbir and Maria Szuppe, 541–53, XXI–XXIII. Eurasian Studies 14. Rome/Halle-Wittenberg: Istituto per l’Oriente/ Orientalisches Institut der Martin-Luther-Universität.

———. 2016. Mitteliranische Handschriften, Teil 2: Berliner Turfanfragmente Buddhistischen Inhalts in Soghdischer Schrift. Vol. 18 (2). VOHD. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

———. 2018a. “Manichäisch Oder Christlich? Detektivische Arbeit an Einem Soghdischen Turfanfragment.” In Der östliche Manichäismus Im Spiegel Seiner Buch- Und Schriftkultur, edited by Zekinie Özertural and Gökhan Şilfeler, 97–104. Berlin: De Gruyter.

———. 2018b. Mitteliranische Handschriften, Teil 3: Berliner Turfanfragmente Christlichen Inhalts Und Varia in Soghdischer Schrift. Vol. 18 (3). VOHD. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Reeves, John C. 2011. Prolegomena to a History of Islamicate Manichaeism. Sheffield/Oakville: Equinox Publishing.

Shenkar, Michael. 2017. “The Religion and the Pantheon of the Sogdians (5th-8th Centuries CE) in Light of Their Sociopolitical Structures.” Journal Asiatique 305 (2): 191–209.

Shokri-Foumeshi, Mohammad. 2015. Mani’s Living Gospel and the Ewangelyōnīg Hymns. Qom: The University of Religions and Denominations Press.

Sims-Williams, Nicholas. 1976. “The Sogdian Fragments of the British Library.” Indo-Iranian Journal 18: 43–82.

———. 1989. “Sogdian.” In Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, edited by Rüdiger Schmitt, 173–92. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

———. 1992. “Sogdian and Turkish Christians in the Turfan and Tun-Huang Manuscripts.” In Turfan and Tun-Huang. The Texts. Encounter of Civilizations on the Silk Route, edited by Alfredo Cadonna, 43–61. Firenze: Olschki.

———. 2004. “A Greek-Sogdian Bilingual from Bulayïq.” In La Persia E Bisanzio. Convegno Internazionale, Roma, 14-18 Ottobre 2002, 623–31. Rome: Accademia nazionale dei lincei.

———. 2009. “Christian Literature in Middle Iranian Languages.” In The Literature of Pre-Islamic Iran, edited by Ronald E. Emmerick and Maria Macuch, 1:266–87. A History of Persian Literature 17. London: Tauris.

———. 2011. “A New Fragment of the Book of Psalms in Sogdian.” In Bibel, Byzanz Und Christlicher Orient: Festschrift Für Stephen Gerö Zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Dmitrij Bumazhnov, Emmanouela Grypeou, Timothy B. Sailors, and Alexander Toepel, 461–65. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 187. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters.

———. 2012. Mitteliranische Handschriften, Teil 4: Iranian Manuscripts in Syriac Script in the Berlin Turfan Collection. VOHD, 18 (4). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

———, ed. 2014. Biblical and Other Christian Sogdian Texts from the Turfan Collection. Vol. 32. Berliner Turfantexte. Turnhout: Brepols.

———, ed. 2019. From Liturgy to Pharmacology: Christian Sogdian Texts from the Turfan. Vol. 45. Berliner Turfantexte. Turnhout: Brepols.

Sundermann, Werner. 1986. “Bruchstücke einer manichäischen Zarathustralegende.” In Studia Grammatica Iranica. Festschrift für Helmut Humbach, edited by Rüdiger Schmitt and Prods O. Skjærvø, 461–82. München: Röll.

———. 1995. “Die Parabel von den schätzesammelnden Kaufleuten.” In Au carrefour des religions mélanges offerts à Philippe Gignoux, publié par le Groupe pour l’Étude de la Civilisation du Moyen-Orient, 285–96. Bures-sur-Yvette: Groupe pour l’Étude de la Civilisation du Moyen-Orient.

———. 2001. “The Book of Giants.” In Encyclopædia Iranica, edited by Ehsan Yarshater, 10:592–94. New York: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

———. 2007. “Eine Re-Edition zweier manichäisch-soghdischer Briefe.” In In Iranian languages and texts from Iran and Turan. Ronald E. Emmerick memorial volume, edited by Maria Macuch, Mauro Maggi, and Werner Sundermann, 403–21. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Tremblay, Xavier. 2001. Pour une histoire de la Sérinde. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

———. 2007. “The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks Before the 13th Century.” In The Spread of Buddhism, edited by Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacher, 75–129. Handbook of Oriental Studies 8: Central Asia 16. Leiden: Brill.

Whitfield, Susan, and Ursula Sims-Williams, eds. 2004. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. London: British Library.

Wilkens, Jens. 2000. Alttürkische Handschriften, Teil 8: Manichäisch-türkische Texte der Berliner Turfansammlung. VOHD, 18 (3). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Yoshida, Yutaka. 1979. “On the Sogdian Infinitives.” Ajia Afurika Gengo Bunka Kenkyū (Journal of Asian and African Studies) 18: 181–95.

———. 1980. “On the Dialectology of Christian Sogdian.” Bulletin of the Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan 23: 83–93.

———. 1983. “Manichaean Aramaic in the Chinese Hymnscroll.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 46: 326–31.

———. 2000. “First Fruits of Ryūkoku-Berlin Joint Project on the Turfan Iranian Manuscripts.” Acta Asiatica: Bulletin of the Institute of Eastern Culture 78: 71–85.

———. 2005. “Excavation of Shi’s Tomb of the Northern Zhou Dynasty at Sabao Near Xi’an.” WenWu (Cultural Relics) 3: 4–33.

———. 2009. “Buddhist Literature in Sogdian.” In The Literature of Pre-Islamic Iran, edited by Ronald E. Emmerick and Maria Macuch, 1:288–329. A History of Persian Literature 17. London: Tauris.

———. 2012. “New Turco-Sogdian Documents and Their Socio-Linguistic Backgrounds.” In Yu Yan Bei Hou de Li Shi: Xi Yu Gu Dian Yu Yan Xue Gao Feng Lun Tan Lun Wen Ji [the History Behind the Languages: Essays of Turfan Forum on Old Languages of the Silk Road], edited by Xinjiang Tulufanxue Yanjie yuan [Academia Turfanica], 48–59. Shanghai: Shanghai Gusi Chubanshe.

———. 2013a. “Buddhist Texts Produced by the Sogdians in China.” In Buddhism Among the Iranian Peoples of Central Asia, edited by Matteo Chiara, Mauro Maggi, and Giuliana Martini, 1:155–79. Multilingualism and History of Knowledge. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Wissenschaften.

———. 2013b. “Heroes of the Shahnama in a Turfan Sogdian Text: A Sogdian Fragment Found in the Lushun Otani Collection.” In Sogdijcy, Ix Predšestvenniki, Sofremenniki I Nasledniki [Sogdians, Their Precursors, Contemporaries and Heirs], 201–18. St. Petersburg.

———. 2015. “A Handlist of Buddhist Sogdian Texts.” Kyōto Daigaku Bungakubu Kenkyū Kiyō [Memoirs of the Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University] 54: 167–80.

———. 2017a. “Chūgoku Torufan Oyobi Sogudiana No Sogudo Jin Keikyōto_Ōtani Tankentai Shōrai Saiiki Bunka Shiryō 2497 Go Teiki Suru Mondai [Christian Sogdians in China, Turfan, and Sogdiana: Problems Raised by a Christian Sogdian Text Ōtani 2497].” In Ōtani Tankentai Shūshū Saiki Kogo Bunken Ronshū Bukkyō, Manikyō, Keikyō [Essays on the Manuscripts Written in Central Asian Languages in the Otani Collection: Buddhism, Manichaeism, and Christianity], edited by Takashi Irisawa and Koichi Kitsudo, 155–80. Kyoto: Research Institute for Buddhist Culture, Ryukoku University and Research Center for World Buddhist Cultures, Ryukoku University.

———. 2017b. “Relationship Between Sogdiana and Turfan During the 10th-11th Centuries as Reflected in Manichaean Sogdian Texts.” Journal of the International Silk Roads Studies 1: 113–25.

———. 2018. “On the Sogdian Version of the Lengqie Shiziji and Related Problems.” Asian Research Trends New Series 13: 1–30.

———. 2019a. “On the Sogdian Prātihārya-Sūtra and the Related Problems: One Aspect of the Buddhist Sogdian Texts from Turfan.” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung 72 (2): 141–63.

———. 2019b. “Some New Interpretations of the Two Judeo-Persian Letters from Khotan.” In A Thousand Judgements: Festschrift for Maria Macuch, edited by Almut Hintze, Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst, and Claudius Naumann, 385–94. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

———. 2019c. Three Manichaean Sogdian Letters Unearthed in Bäzäklik, Turfan. Kyoto: Rinsen Book Co.

———. 2020a. “Introduction.” Edited by Yutaka Yoshida. Acta Asiatica 119: Sogdians in Sogdiana, China, and Turfan During the Sixth Century, iii–ix.

———. 2020b. “Sogudogo No Mikkyō Kyōten to Semirechie Bukkyō [Some Problems Surrounding Sogdian Esoteric Texts and the Buddhism of Semirechi’e].” In Teikyō Daigaku Bunka Zaiken Kenkyū Hōkokushodai, 19:193–203.

Zieme, Peter. 2015. Altuigurische Texte Der Kirche Des Ostens Aus Zentralasien [Old Uigur Texts of the Church of the East from Central Asia]. Gorgias Eastern Christian Studies 41. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.