Buddhist Indian Loanwords in Sogdian and the Development of Sogdian Buddhism

Buddhist Sogdian texts contain about 300 loanwords of Indian origin excluding the ones that are known also in Manichaean, secular, or Christian Sogdian texts. About sixty percent of these can easily be seen to be borrowed from Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. A further twenty percent or so are not so easily recognized as from that source because they also reflect linguistic developments within Sogdian. Another twenty percent are from a Prakrit or show the intermediation of another language, such as Parthian (probably including pwty ‘Buddha’), Tocharian, or Chinese. About one percent has unclear sources. The Indian loanwords in Manichean, Christian and secular Sogdian texts, in contrast, are in the majority from a Middle Indian source. In Buddhist Sogdian, the narrative texts like the Vessantara Jātaka feature more of the less regular loan shapes, which suggests a different path of transmission and probably an earlier date. An appendix discusses the role of Buddism in Sogdiana from finds there: personal names reflect the divinity of the Buddha; a wooden plaque with a devotional scene was recently discovered in Panjakent; a seal from Kafir-kala depicts a Turkish noblewoman rather than a Boddhisatva. A study of place names indicates the presence of Vihāras (Nawbahār, Farxār) at the gates of several main cities in and around Sogdiana.

Sogdiana, Buddhist Sogdian texts, Old and Middle Indo-Aryan, Middle Iranian, Chinese Tripiṭaka, translation technique, Buddha images, toponymy

Introduction: Status Quaestionis

The problem of Sogdian Buddhism has long been a focus of research of both philologists and archaeologists studying this ancient East Iranian people of Central Asia.1 The discovery of Sogdian Buddhist texts in the early twentieth century in Dunhuang and Turfan (along with Buddhist texts in another middle Iranian vernacular, Khotanese, as well as Tocharian languages, Gāndhārī Prakrit, Uyghur, Chinese and Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit) was initially perceived as an indication of Iranian transmission of Mahāyāna Buddhism from the Indian subcontinent into China. It was soon realized, however, that the majority of the Sogdian Buddhist compositions were translations from Chinese and that these texts could not be a source of the Chinese Tripiṭaka. Some decades later, extensive archaeological excavations in Soviet Central Asia indicated that on the territory of Sogdiana proper, i.e., in the Zeravshan and Kashka-darya valleys as well as adjacent territories to the north, the traces of Buddhism were very scarce (unlike in Bactria, Merv, or the Chu valley in Semirechie).

The historical records often confirm the absence of Buddhism in Sogdiana but sometimes they do not. Xuanzang 玄奘 (around 630) mentions two vihāras in Samarkand and the hostile attitude of the local people and the king, who did not follow the law of Buddha (tr. Beal 1911, 45–46). Huichao 慧超 some hundred years later mentions one monastery and one monk who moreover did not know how to rever Buddha properly (Yang et al. 1984, 54). In the Xin Tangshu, chapter ccxxib, however, Sogdiana is said to honour Buddhism and to worship the ‘celestial god’ (tr. Chavannes 1903, 135); Weishu (102.2281) and Jiu Tangshu (198.5310-11) simply state Sogdians believe in Buddha and that Buddhist dharma is widespread (tr. Huber 2020, 30, 51). The Muslim bibliographer Ibn al-Nadīm wrote in the tenth century that al-Samaniyya (*Shamaniyya, Buddhism) was the first religion of Transoxiana (tr. Dodge 1970, 801–2).

After more than 100 years of investigation, all the Buddhist Sogdian texts from Dunhuang in the collections of Paris, London, St. Petersburg and Kyōto have been published. The publication of the Berlin collection, which comprises materials from Turfan, usually in very fragmented condition, is constantly increasing. The catalogue of the collection, prepared by Christiane Reck (2016), is abundant in detail and apparatus, so all the proper names, the Buddhist special terms, and the unclear words from the whole collection are put in very helpful indexes. At present, scholars can effectively access the overall picture of the surviving Sogdian Buddhist literature through the available publications without significant lacks.2

Sogdian Buddhist literature has been revisited several times during this century. The most recent overview articles are written by Yutaka Yoshida (2009, 2013, 2015). His articles on particular subjects which are most useful to our subject are that of 2008 with an analysis of the word Bodhisattva in Sogdian and Tocharian loanwords; that of (2013), where he advocates the ‘colonial’ nature of Sogdian Buddhism; and that of (2019a), where a group of texts from the (Mūla)-Sarvāstivādin tradition of the northern Tarim Basin is highlighted. In another article (2017), he proposes that the blossom of Sogdian Buddhism did not start before the mid-seventh century.3

The subject of the first two chapters of the present paper, the Buddhist Indian loans in Sogdian, has been treated in several papers. D. Neil MacKenzie compiled a glossary of Sogdian translations of Buddhist Chinese terms and names with their Indian parallels (1972, 1976, 179–220). Nicholas Sims-Williams (1983) offered a survey of Indian loans in Parthian and Sogdian, and although he refrained from scrutinizing Buddhist material (“The Indian terms in use in the Buddhist Sogdian are too numerous to be surveyed in detail here,” 137), the observations on the loanwords attested in Manichaean/Christian as well as Buddhist texts and on the borrowings from Middle Indic are very important. In 2010, Yutaka Yoshida published a concise treatment of variations in Indian borrowings in Sogdian Buddhist texts where he proposed to divide them into several groups according to the degree of naturalization in Sogdian. All the proper names of Indian origin found in published Sogdian texts were collected by Lurje (2010). Finally, a long article of Elio Provasi (2013) surveys 68 names borrowed from Indic into Sogdian, paying great attention to various Central Asian forms and especially ones found in the Chinese Tripiṭaka.

In this paper we aim to survey the almost 300 attested Indian borrowings in Sogdian Buddhist texts, including proper nouns, in order to disclose the main devices of transliteration used by Sogdian scribes and to show that these devices presuppose Buddhist (Hybrid) Sanskrit4 as the main source (chapter 3. h.). Cases of deviations caused by intra-Sogdian transmission or the mediation of other languages are surveyed in section 3. Section 4 provides an update on the Buddhist remains discovered in Sogdiana proper after the standard surveys of Mkrtychev (2002) and Compareti (2008). It also includes a discussion on the anthroponymy of the Sogdian Buddhists and on the Buddhist toponymy of Sogdiana and her neighbours, thus trying to illuminate some features of the modus vivendi of Sogdian Buddhism.

2. Conventions of Borrowings from Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit into Sogdian

I have collected almost 300 borrowings from Indian that are recorded in Sogdian exclusively in Buddhist texts that mirror the ideas, concepts, names, and place names of the teaching. With this material I attempt to show the conventions of rendering Indo-Aryan phonetics into Sogdian.

My working hypothesis is that Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit was the source of the major part of the borrowings without mediating traditions. The principal method is to explain the material as far as possible as regular loans or as loans that change their shape within the Sogdian language. I further elaborate this research background under section 3. h.

Many of the forms quoted below are hapax legomena in Sogdian and appear only once or only in one text. Some others, however, are attested in several texts in (almost) identical forms, and if these texts are distant from one another (e. g., one coming from Dunhuang and another from Turfan)5, we can consider them rather established technical lexica among Sogdian Buddhists. It is natural that the more essential the concept is to the teaching, the more chance it has to be well established in the Sogdian Buddhist lexicon. Most of these lexemes, however, are occasional borrowings.

In the course of the discussion, we must form a clear borderline between the purely Buddhist borrowings6 and the loan words that are attested in other variants of Sogdian, the Manichaean, Christian, and secular, since, as it is well known (especially Sims-Williams 1983), the shape and the contexts of these loans were different. The forms that appear both inside and outside Buddhist Sogdian texts are excluded from the list below but are often mentioned in the footnotes. I am aware that some loans might have been overlooked. I tried to include the whole corpus in the Index and to use each loan at least once in the body of the article.

Almost all Buddhist Sogdian texts are written in the inherited West-Semitic quasi-alphabet, with its obvious limitations regarding exact phonetic recording. This means that vowels can be rendered with so-called matres lectionis (’aleph, waw, yodh) and their combinations, or they can be left unrecorded. Many oppositions (such as distinction of voiced and voiceless stops: k and g, č and ǰ, t and d, p and b) were weakly differentiated (while voiced stops appeared mostly in special positions and loanwords, as we can judge from Manichaean and Christian Sogdian texts written in more exact orthography). Some essential features of Indo-Aryan phonology (such as aspirate/non aspirate stops, retroflex consonants) were unknown to Sogdian (as to many other Iranian tongues), and the inflection in the target language was largely reduced as compared to the distantly read Sanskrit.

We will start the analysis with consonants arranged according to the Sanskrit alphabetization sequence, follow with the vowels and end with the rendering of word endings. Our primary reference on the Indian side is Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. For the sake of simplicity, in the body of the article the lexicographical sources will be omitted, but briefly listed in the index.7 We try to reconstruct more or less strict rules of rendering which can be applied to as many borrowings as possible. Later, we shall examine some special substandard cases with re-etymologization, mediation of other languages, etc.

i. Consonants

a. Back Consonants k, kh, g, gh, ṅ. All these stops are always rendered with Sogdian k (which could be pronounced as /k/ or /g/): knkmwny – Kanakamuni; kntrβ – gandharva; ’’m(’)wkp’š – Amoghapāśa.

The groups ṅk, ṅg are rendered as nk: rnk’/lnk’ – Laṅkā; knky(h) – Gaṅgā8. Internal k is often geminated in writing: ckkr – cakra; rkš, rkkš – rakṣā.

In a few cases we see that Indian suffixal k is recorded as (’)y, which interchanges with spelling with (’)k(k): ’wp’s’y, wp’s’k, ’wβ’s’k – upāsaka; βyr’wr’y, βyr’wt’kk, βr’wr’k – Virūḍhaka; maybe nysrky – niḥsargika. Similarly an expected k can be omitted after long ā: pr’’, pr’kh, Pl. pr’tt’ – paṭāka. We return to this problem later (see 2.s; 3.b).

One should notice explicitly the single occurrence of writing back stops as x or γ so far in the corpus: ’n’wγt’r’ s’m myγ s’m pwδ’y – anuttarasamyaksaṃbodhi.9 This has long been considered a Chinese loan (Gauthiot and Pelliot 1926, 2:66; see also under 3. g.).

b. Palatal consonants: c, ch, j, jh, ñ. Usually c and j are rendered as c: cynt’’mny – cintāmaṇi; ’’c’r’y – ācārya; βcrp’n – Vajrapāṇi. I have not found cases of jh in the borrowings. The only case of aspirate ch is in geminated cch and is rendered as šc: ’yšcyntyt, ’yšc’tyk – icchantika or c: kycrwnmyl – kr̥cchronmīla.10

It is not uncommon to see j rendered as t: p’štsyn – Bhaiṣajyasena; rwk’yntr r’t – Lokendra rājan.11 There are no cases of j simplified into y recognized so far, on kršny’n see 3. a, 3. i. below.

ñ is rendered as n: kncnsr – Kāñcanasāra and sometimes as ny: ’’tny’tkwtyn – Ājñātakauṇḍinya; pr’tny’p’rmyt, prtnyh p’rmyt – prajñāpāramitā. The initial group jñ appears as ny in ny’ncynt – Jñānacinta (the name of translator, not the character in doctrinal text; compare see Pāli ñāṇa, Gāndhārī ñāna = Jñāna, Toch. B. Ñāna- in personal names).

In one special case j is rendered as both c and z: r’zβwrt, r’cβrt – Rājyavardhana (in the same text)12 and in one case probably as š: ’ykr’šn - ekarājan.

c. Retroflex ṭ ṭh ḍ ḍh are rendered through t and r: For ṭ, the variant t seems to prevail: kr’ytkwt – Gr̥dhakūṭa; šr’ykwty – Śrīkūṭa, with the exceptions of n’r(kr’k) – nāṭa; pr’’ – paṭāka. I do not have reliable examples for ṭh. ḍ is either t or r: kr’wr – Garuḍa and βcrkr’wt – Vajragaruḍa; cwrypnt’kk – Cūḍā̆panthaka and mncwty – Maṇicūḍa. The same pattern holds for the rarer ḍh: βyr’wr’y, βyr’wt’kk, βr’wr’k – Virūḍhaka. There is no attested usage of δ for retroflexes and, moreover, there are no cases of spelling Indian retroflexes through /l/ (which is recoreded in some Sogdian texts through a newly invented letter or variation of r and δ), unlike in Khotanese and Tocharian B. A special case is kwrt(t)y, kwtty – koṭi.13

ṇ is normally rendered as n: β’yšrβn – Vaiśravaṇa; nyrβ’n – nirvāṇa: βynwβn – Veṇuvana.14

The group ṇḍ is often rendered as ntr: tntr’k – Daṇḍaka;15 mntr – maṇḍa. But it remains nt in cnt’’r – Caṇḍāla; kntyk – Ghaṇṭikā and is simplified in ’’tny’tkwtyn – Ājñātakauṇḍinya. The rendering is unclear in pwntr’yk – puṇḍarika.

Some irregular changes can be the result of elimination of haplology, such as the loss of ṇ in ’’tny’tkwtyn – Ājñātakauṇḍinya, and the loss of ṭ in snk’swtr – Saṃghāṭasūtra (see 3. a).16

d. Dental t, th, d, dh, n. The voiceless stops are usually rendered as t, and often as tt in non-initial position: tr’ymwkt – Trimukti; pr’ttymwkš – prā̆timokṣa; ’yry’’pt – īryāpatha; p’rmyt – pāramīta. An Indian geminate often remains the same: pt(t)r – pattra (the word seems to be restricted to Turfan texts), δyβδtt – Devadatta. T(h) transcribed δ(δ) is limited to non-initial position but fairly common (see. under 3. e): k’wδ’m, k’wt’m – Gautama; ’’ry’βrwkδyšβr – Ārya Avalokiteśvara. T in the cluster tp is lost in (’)wpδ(’)y – utpala (compare Gāndhārī upala, Pāli uppala, Toch. B. uppāl, A oppal), and in the final position in twškr–duṣkr̥ta.

d can be rendered as t and δ in any position, and for dh the latter prevails. Initial d is δ: δyβdtt – Devadatta. Initial d is t: twškr – duṣkr̥ta. Non-initial d is t: mx’tyβ – mahādeva. d is δ: šrγw swδ’s – Siṃhasaudāsa. Initial dh is δ: δy’(’)n(y) – dhyāna. Initial dh is t: t’rn’y – dhāraṇī. Non-initial dh is δ: s’δw s’δw – sadhu sadhu. Non-initial dh is t: syt(t) – siddhi, srβ’’rtt sytt – Sarvārthasiddha. Variation occurs in βytty’tr / βyty’δr – vidyādhara. D after n is always spelled t: cntn – candana.

Geminate ddh results once in nt in šnt’wδn – Śuddhodana, and r renders dh in s’m’’r – samādhi17; we consider these forms irregular; one sees a diacritic sign in kr’ẉt’ – krodha (invocation).

Indian n is always n in Sogdian: n’t’y k’š’yp’ – Nadī Kāśyapa; mx’y’n[y] – Mahāyana. N is lost in δ’p’t – dānapati and d is simplified to y in k’wy’ny, kwy’n’ – Godānīya (see under 3. g).

e. Labials p, ph, b, bh, m. All stops are regularly rendered by p in all positions: pr’pt – Prāpta; pyms’r – Bimba/isāra; ptrp’r – Bhadrapāla; mx’kp(’)yn – Mahākapphiṇa; ’wrpyrβ’ k’š’yp’ – Urubilvā (Uruvilvā) Kāśyapa; kwp’yr – Kubera (invocation); βyšβ’pw – Viśvabhu.

m usually appears as m: mnc’wšyry – Mañjuśrī; c’δysm’r – Jātismara, kr’’m – grāma; but before p, n can be written: rnpyh – ḍomba; s’δynp’y’ – sālambha.

Sogdian β for the stops is rare and is known in a few cases in non-initial position: ’wβ’s’k18, ’wβ’s’nc ’wp’s’k – upāsaka, upāsikā; prβr’c – Prabhārāja.19 In ṗykšw – bhikṣu the diacritic writing <ṗ> probably indicates /b/ (Sims-Williams apud MacKenzie 1976, ii 9, note. 37).

f. Sonorants r, l, y, v do not follow a unitary rule. R is always rendered as r: rkkš – rakṣā; ’’s’wr – Asura; βrδ’(m)[ – Vardhamānamati (?). When several R-like sounds are in the source, one r sometimes drops out: kr’ytkwt – Gr̥dhrakūṭa or Gr̥ddhakūṭa; trytr’št – Dhr̥tarāṣṭra; βympx’r – Vimalaprabhāsa, but š’rypwtr – Śāriputra. A non-etymological r appears in βrx’r – vihāra (see 4. d), as well as in kr’ẓ’k (nγ’wδn) – kāṣāya, for which numerous Central Asian variations have been documented (Bailey 1949, 130).20

l can be treated in three ways, as the newly shaped letter l (ṛ) in some relatively late texts, as r or (somewhat less commonly) as δ: lnk’, rnk’ – Laṅkā(vatāra-sūtra); δwk’ – loka; kδp klp krp-h – kalpa; ptr klp(-) – bhadrakalpa; p’r’wr – balūla; stwl(’nc) – Sthūlā(tyaya). Yutaka Yoshida (2010, 90) noticed that the spelling with δ is common among well-established Sogdian terms. Manichaean writing δwk- (and not lwk) might indicate a fricative /δ/, and not a sonorant pronunciation, compare also prδwk’ – paraloka; but rwkδ’t – lokadhātu.

In two instances, postvocalic l and r are written as n: ’ncn(δst) – añjali21 and p’n nyrβ’n parinirvāṇa (see under 3. g).

Y is rendered as y: ywcn – yojana; βyny – vinaya; p’ytyk – pāyattika, pātayantika; βy’y’m – vyāyāma; kš’try – kṣatriya.

Quite often, post-consonantal y is lost: cwδ’yk’ c’wtyšk’ – Jyotiṣka; p’štsyn, p’tsyn – Bhaiṣajyasena; ’’tny’tkwtyn – Ājñātakauṇḍinya; ’’s’nk(y) – asaṃkhyeya. One can explain in the same way š’kmwn from š’kymwn – Śakyamūni. The first form appears in Manichaean Sogdian and has been explained as Prakritic (Sims-Williams (1983), 137; š’kymwn in a Manichaen text is largely a restoration, see Lurje (2010), 365). Consequent simplifications are observed in mwtkr’’y’n, mwtklyn – Maudgalyāyana.

Another common feature is metathesis of non-initial ya, ye into ’y (pronounced as /e/?): ’’c’r’y – Ācārya; k’š’yp – Kāśyapa; prt’ykpwt(t) – pratyekabuddha. See under 2. m. for the opposite case.22

Indian v is always rendered as β in Sogdian: β’yšrβn – Vaiśravaṇa; β’swmytr – Vasumitra.

In few exceptional cases it is recorded as p: srp’šwr as variant for srβšwr – Sarvaśūra in the Saṅghāṭasūtra; pwrpδ’yš – *Purvadeśa and synt’’p – saindhava.23 I did not notice any case of Sogdian w for Sanskrit v.

g. Sibilants ś ṣ s h. The first two are regularly rendered by š: š’ky– Śākya; β’yš’ly – Vaiśālī; wšn’yš – uṣṇīṣa; (p)wrβ’š’(t) – Pūrvāṣāḍhā;24 snk’’βšyš – Saṃghāvaśeṣa; š’str – śāstra.

Twice in the corpus ṣ appears as ẓ /ž/: twẓ’yt βγyst’n – Tuṣita-Heaven (but sntwšʾyt – Santuṣita) and rz’y (usually rš’’k) – r̥ṣi.25 The group kṣ simplifies into š in š’ymnkr (alias kš’ymnkr cf. inscriptional Tocharian B Ṣemaṅkar-) Kṣemaṃkara. Ṣ is lost in p’tsyn – Bhaiṣajyasena. All these cases are either archaic, dialectal or clerical errors.

S is also rendered as s in a straightforward way: srβ’stβ’t – sarvāstivāda. There is one case of r /l?/ for Sanskrit s in βympx’r – Vimalaprabhāsa.26

Indian h can be rendered through x or less commonly with no sign in Sogdian (no cases of initial h recognized so far): pr’xmn / pr’m(’)n – brāhmaṇa; ’r’x’n, rx’nt- (Manichaean rhnd!) – arhat; r’ckr(’)y – Rājagr̥ha. Skt. mahā (when not translated) is always rendered as mx’-: mx’r’c – mahārāja; mx’stβ – mahasattva; mx’yšβr – Maheśvara.

h. Visarga (ḥ), anusvāra (ṃ) Since endings will be treated separately, and these signs have limited usage in non-final position, the documentation is scarce. Visarga is not recorded in nysrky[ – niḥsargika, and anusvāra appears as n (k)š’ymnkr – Kṣemaṃkara; snk’ – saṃgha; snkr’m – saṃghārāma; typ’nkr – Dīpaṃkara ( all before back consonants) or m: smyk’ smpwtt – samyaksaṃbuddha (before labial), smrk – saṃrāga; the common snks’r – saṃsāra is unusual; recently N. Sims-Williams (2021, 34–35) proposed to see here a contamination with saṃskāra. In final position, it is m or n: ’wm – oṃ; pk’’β’n (in Skt invocation; see 3. g.) – Bhagavant, nom. Bhagavāṅ; ’’ry’nc – āryaṃ ca (invocation: before c).

ii. Vowels

i. Short a is rendered as single or double aleph in the beginning and single aleph or more often no sign in the middle of a word: ’’m’(w)kp’š – Amoghapāśa; ’pyδrm – abhidharma; βyp’š – Vipaśyin; knkmwny – Kanakamuni ; m’k(’)t – Magadha.

Fronting to y, ’y sometimes occurs: prsn’ycy – Prasenajit; ’yšcyntyt, ’yšc’tyk – icchantika; βymyrkr’yt (and βymrkyrt) – Vimalakīrti; k’r’ynt knδh, k’r’ynk’ – Kalandaka /Karaṇḍa / Kaliṅga; s’δynp’y – sālambha. Initial a can be lost in ’psm’r / psm’r – apasmāra.

Long ā is always double aleph initially and single or double medially: ’’ry’βrwkδyšβr – Ārya āvalokiteśvara, cnt’’r – Caṇḍāla, βyr’wp’kš – Virūpākṣa, p’tr – pātra, šr’’βk – śrāvaka. Shortenings are uncommon: tn(’)pt – dānapati; kncnsr – Kāñcanasāra27, prβr’c – Prabhārāja. On the probable articulation of single and double initial aleph in loanwords in Sogdian see Sims-Williams (1983, 138–39).

j. In initial position i and ī are usually rendered as ’y: ’yšcyntyt, ’yšc’tyk – icchantika; ’yšβr – īśvara, once as y: yntr’y – indrāya (Skt Dative). In medial position, the most common is y: βykn βyn’ywkh – vighnavināyaka; kntyk – ghaṇṭikā, but ’y or no sign are attested rather widely, too: kpl[β]st, kp’yrβst – Kapilavastu; ’’βcy, ’’βycy, ’’βyc – avīci; kwmp’yr – kumbhīra; kšytkrp – Kṣitikalpa.

Metathesis is visible in βymyrkr’yt – Vimalakīrti; the group śr is often changed into šyr (a result of reetymologization, see 3. a. below): mnc’wšyry – Mañjuśrī (also BHS Mañjuśiri); kwm’ršyr – Kumāraśri; šyr’’βsth – Śrāvastī.

k. Initially u is rendered as ’w or w: ’wp’k’ – Upāka; ’wβ’s’k, wp’s’k – upāsaka; wpʾtyʾy – upādhyāya. In medial position u and ū are mostly rendered as w or ’w as well: ’’s’wr – asura; pwšpcwty – *Puṣpacūḍa; kwm’r – kumara; δ’wt’ – dhūta; m’ywr – mayūra; n’ywt – nayuta; pwr’wš – Puruṣa. Unusual is sywpwδ’y – Subhūti;28 šnt’wδn – Śuddhodana.

l. Skt r̥ is attested only in rz’y, rš’’k – r̥ṣaya in the beginning and more often in non-initial position. It is rendered as r or r(’)y: kr’ytkwt – Gr̥dhakūṭa; r’ckr – Rājagr̥ha; trytr’št – Dhr̥tarāṣṭra; twškr – duṣkr̥ta; m’trk š’str – mātr̥kā-śāstra-. The vowel l̥ is absent within the corpus I could collect.

m. Initially e is attested once and rendered as ’y: ’ykr’šn – ekarājan. In medial position, e is ’y, y: δyβδtt – Devadatta; nymyš – nimeṣa; pr’yt – preta; rarely y’: ’rny’m / ’rn’ym – Araṇemi (see under 2f), pwtkšy’tr / pwt(’)kš(’)ytr – Buddhakṣetra. It is aleph in Sanskrit invocation: cnt βcrp’n’y mx’’k’y s’n’pt’y – Caṇḍavajrapāṇaye mahākāye senāpate.

Medial ai can be rendered as ’y, y or even no sign: β’yš’ly – Vaiśālī; βyr’wcn – Vairocana; pyš’ckwr – Bhaiṣajyagūru; cntrβrwcn – candravairocana. Note aleph for ai in p’štsyn, p’tsyn – Bhaiṣajyasena.

n. Initially, o is once rendered as ’w: ’wm – oṃ. In medial position, o and au are usually ’w or w: cwδ’yk’, c’wtyšk’ – Jyotiṣka; mwkš – mokṣa; k’wšyk’ – kauśika; mwtklyn, mwtkr’’y’n – Maudgalyāyana; k’w šwt – semi-translating Gocara. Unusual are rnpyh – ḍomba and ’’m’kp’š – Amoghapāśa (var. ’’m’wkp’š).29

o. On non-etymological prothetic vowels, see 3. b.

iii. Endings

p. As it is well known, in Sogdian ‘light’ and ‘heavy’ stems are distinguished. The former are ones with no long vowels or diphthongs, the latter have at least one long vowel or diphthong. In the nominal inflection in singular, ‘light’ stems differentiate gender and six cases while ‘heavy’ stems have only direct and oblique cases. The major part of the Indian loanwords in Sogdian are ‘heavy’ stems that have zero ending in Rect. Sg., /-i/ in Obl. Sg, /-t/ in Rect. Pl and /-ti/ in Obl. Pl as well as vocative in /-a/.

The Indian loans that follow, with some reservations, the ‘light’ stem pattern are pwty – Buddha; rtn- – ratṇa; šmn- – śramana; smwtr- – samudra; ykš- – yakṣa; ’st’wp- – stūpa.30 The rendering of Gaṅgā, nom. knk’ (see n. 8) and gen. knky(h) might represent feminine ‘light’ stem.

What concerns us here more is the rendering of Skt endings in Sogdian inasmuch as we can detect them within the declension of the different language.

q. The thematic -a ending is naturally most common among the borrowed lexemes. It is lost in the majority of cases: ’’n’nt – Ānanda;31’’kš’r – akṣara (?). Sometimes it is rendered as ’: mx’k’š’yp’ – Mahākāśyapa;32 s’l’ ryzkry xwβw – Sāla-Īśvararāja. Elio Provasi (2013, 277–78) supposes that the loans with aleph for final -a are to be placed in time between the earliest Prakritic forms and the standard transliterations from Sanskrit, as in Chinese Buddhist borrowings, but I do not find definitive proof. The recording of final -a as aleph seems to be more common after k, probably in order to avoid reading /-e/: snk’ – saṃgha; δwk’ – loka; smyk’ smpwtt – samyaksaṃbuddha; ’wp’k’ – Upāka; šl’wk, šr’wk(’) – śloka. It is lost in declentional forms: n’k’, pl. n’kt – nāga (also Manichaean); pwtr’ky (obl) – Potalaka.

In a few isolated cases we see final a as y or -’y: mncwty – maṇicūḍa; rtncwty – Ratnacūda; swβrncwty – Suvarnacūda; swttršny – Sudarśaṇa; pwrn’y – Pūraṇa.33 The final Sogdian h, which can be purely graphical marker or convey -ā̆ is sometimes attested too: kδp klp krp-h – kalpa.34

r. Feminine -ā is usually rendered as ’, ’h or h: mx’m’yh – mahāmāyā; yš’wδrh – Yaśodharā; ’’š’h – Āšā; ’wrpyrβ’ k’š’yp’ – Urbilvā Kāśyapa; k’y’’ k’š’yp’ – Gayā Kāśyapa; βc’ – vacā ‘Acorus calamus’. This writing might indicate a final /-ā̆/. A zero ending is probably attested in kntyk if it is ghaṇṭikā, mwtr – mudrā; note variants šβ’kwšh, šβk’wš, šyβkwš, šyβkwšh etc. – Śivaghoṣā.

s. The masculine -i and feminine -ī is either rendered with -y or not recorded: ’’βcy, ’’βycy, ’’βyc – avīci; š’r’βst, šyr’’βsth – Śravastī; syt(t) – siddhi; m’ytr – maitrī (or maitrā, also in Manichaean); β’yš’ly – Vaiśālī, rtnkyrt – Ratnakīrti; swk’βty – Sukhāvatī. Digraph ’y appears in šβ’y, šβ’’y – Śivi; t’rn’y – dhāraṇī. In rz’y, rš’’k – r̥ṣi, BHS r̥ṣaya it alternates with ’’k which would indicate spelling /rišē/, see 3. b.

t. Similarly, -u can be recorded with or without final w or ’w: s’δw s’δw – sadhu sadhu; r’xw – Rāhu; rwkδ’t – lokadhātu; m’δ’w – Madu; kpl[β]st, kp’yrβst – Kapilavastu. One can notice that the final y and w are more common in monosyllabic bases. The form pykš’k (Manich. pykšy) – bhikṣu, unlike pykšw, is quite unusual.

u. The final n of athematic endings is often not preserved and the preceding vowel may or may not be preserved (see Kasai 2015, 405, 413 for Uyghur): ’’n’k’my – anāgāmin, nom. anāgāmī; βyp’š – Vipaśyin, Vipaśśin (L, P), ckkrβrt – cakravartin, nom. cakravartī; rwk’yntr r’t – Lokendra rājan, nom. rājā; kwm’rβ’s – Kumāravāsin; it is preserved in rtnšykyn – Ratnaśikhin, but šyky – Śikhin; ’ykr’šn – ekarājan.

v. Final t is not recorded in prsn’ycy – Prasenajit, compare Pali Pasenadi, Toch A. Prasenaji, B Prasenaci, Old Turkic Prasaniči. In -nt stems we see ending n or nt35, ’r’x’n, rx’nt (also in Manichaean rhnd) – arhant, nom. arhāṇ.

w. In general, Sogdians tended to borrow words in the nominative singular form rather than the base. Sometimes we notice Indian cases other than the nominative, especially in dhāraṇis: kry’n ’sy’ pykšw – Kalyaṇasya bhikšoḥ (genitive); yntr’y – Indrāya (dative); βyr’wkt’yn – vilokitāyāṃ (locative).

As we see, the larger part of Indian Buddhist loanwords in Sogdian follows relatively clear rules of transmission with limited variation which can be put in the following conspectus. In chapter 3. h. I argue that the source of these standard borrowings is Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit as perceived by Sogdians. The loans that follow the rules of this table, which we consider regular, constitute 62 percent of the material at hand.

Conspectus: Standard Buddhist Sogdian Renderings of Sanskrit

Sanskrit (transcription) |

Sogdian (transliteration) |

|---|---|

| Consonants (and some clusters) | |

| k, kh, g, gh | k (-kk)36 |

| ṅ | n |

| c | c |

| j | c, t |

| ñ | n, ny |

| ṭ | t, -r |

| ḍ, ḍh | t, -r |

| ṇ | n |

| ṇḍ | -nt, -ntr |

| t, th, | t (-tt), -δ |

| d, dh | δ, t |

| n | n |

| p, ph, b, bh | p |

| m | m |

| mp | np |

| r | r |

| l | r, l, δ |

| y | y, Ø |

| ya | y’, ’y |

| v | β |

| ṣ, ś | š |

| s | s |

| h | -x, -Ø |

| ḥ | -Ø |

| ṃ | -m,-n |

| Vowels and diphthongs | |

| a | ’’-, ’-, -’-, -Ø- |

| ā | ’’-, -’’-, -’- |

| i, ī | ’y-, y-, -y-, -’y-, -Ø- |

| u, ū | ’w-, w-, -w-, -’w- |

| r̥ | r-, -r-, -ry-, -r’y- |

| e, ai | ’y-, -y-, -’y- |

| o, au | ’w, -’w-, -w- |

3. Special Cases in Rendering

a. Contaminations

As it is evidenced from the conspectus, Sogdian writing did not possess the means for rendering all Indo-Aryan phonological detail. In some parts it was triggered by limitations in Sogdian alphabet or phonetic system, but in others (differentiation of aspirate and non-aspirate consonants and long and short vowels other than a, ā) I could not notice any attemtp of Sogdian scribes to record the distinction. So sometimes the spellings of different words merged: mntr comes from mandala, mantra, and maṇḍa in different contexts37, and perhaps non-etymological n in the name mntr’yh Madrī was triggered by one of these loans (note also the inclusion on n in Chinese, Uyghur and Tocharian forms of the name, Provasi 2013, 230–31; Ogihara 2018, e41).

The last example highlights a feature we see rather often in these borrowings: re-etymologizations on the base of Sogdian or Indian language. We already saw the inclusion of y in the group śr >šyr: kwm’ršyr – Kumāraśri; šyr’’βsth – Śrāvastī; mnc’wšyry – Mañjuśrī.38 In this, an association with S šyr “good, nice” probably played a role. A doublet form of šyr’’βsth: š’r’βst might be affected by Western Middle Iranian word šahr “town, province,” note š’ryst’n in Sogdian Manichaean church history. The spelling cntrsyn for the river Citrasena is probably affected by very common Indian candra “beauty, moon,” while swttrsyn implies virtual Sūtrasena, an unattested(?) but quite Buddhist looking name “army of Sūtras,” based on swttr – sūtra. snks’r – saṃsāra and maybe snk’swtr Saṃghāṭasūtra might be influenced by snk’ saṃgha (differently N. Sims-Williams, see under 2. h). See also discussions on kršny’n – Kr̥ṣṇājinā styled as Sogdian personal name “Boon of Krishna”; ’ykr’šn – *Ēkarājan below.

In the word βykn βyn’ywk’ – vighna vināyaka one can explain w at the end as contamination with S ywk (ywk’ in the Sūtra of Causes and Effects 59) “teaching.” Sogdian sym’βntt, sym βynt’y, if from sīmābandha might be affected by Sogdian βnt “bundle,” βynt- “to bind” with symh “fear” in the beginning. Nārāyaṇa is constantly (in four different texts) rendered in S with aleph in the final syllable, n’r’y’n and not *n’r’yn, as if in contamination with Sogdian names in y’n “boon.” Compare also cytβnt, kyn(n)tr under 3.b; ’yšcyntyt, ’yšc’tyk – icchantika could be influenced by Sogdian ’šcy’n’k “worthy.”

b. Simplifications

The long consonant groups in Sanskrit, especially in compound words, were hardly articulated by a foreigner, so various shortenings took place. We do not witness the insertion of epenthetic (svarabhakti) vowels in the consonant clusters (with possible exception of twr’w(n)[wtn if for Droṇodana), although prothesis or loss of the initial short vowel—in accord with native Sogdian development—is documented: ’knšk – Kaniṣka; ’st’wp- – stūpa; ’psm’r, psm’r – apasamara; ’pr’tyk’ pwt, prt’ykpwt – pratyekabuddha;’kwšty, Brāhmi kuṣṭ(h) – kuṣṭha.

In respect of consonant clusters, ṇ and y are lost in ’’tny’tkwtyn – Ājñātakauṇḍinya (note Gāndhārī A(ṃ)ñadako(ṃ)ḍi(ṃ)ña, Pāli Aññātakoṇḍañña), the syllables na and va probably fall in cyttr’n – Cittanavarāṇa (?), n in kycrwmyl = kr̥cchronmīla, subsequent simplifications we attest in p’štsyn, p’tsyn – Bhaiṣajyasena, r is lost in trytr’št – Dhr̥tarāṣṭra, t falls in sm’nptr, var. sm’nt pwtr, sm’ntpttr – Samantabhadra. These simplifications could result either from Sogdian processes or from a mediating tradition, be it Indic, Iranian, or Chinese. The shortening and metathesis of pwtystβ, pwtsβ, pwδysβt etc. bodhisattva (Yoshida 2008, 347–48) goes along the same lines. The Sogdian tendency to a labial articulation of the vowel between P and D (Sims-Williams 1985, 61, n. to 24R) is visible in sm’nt pwtr – Samantabhadra.

The shortening or shift of vowels in long words may sometimes result from mediation in transmission and may sometimes be a Sogdian development or even inaccuracy in the rendering of long words: cntrβrwcn – Candravairocana; swryβrwcwn – Suryavairocana; prsn’ycy – Prasenajit (see 2. i); prytpkwpt – pratyekabuddha. Abbreviation probably occurred in ’’m’wk – Amogha(vajra?) and rwkδyšβ’r – (Aryāva)lokiteśvara which may be contaminated with Lokeśvara “lord of the world,” which was often used as an epithet of the former Buddha (Brough 1982, 68).

Non-etymological consonants r, n or t, sometimes appear, too: cytβnt – Jetavana forest;39 kyn(n)tr – Kiṃnara;40 šnt’wδn – Śuddhodana.41 Most often discussed in this context is βrx’r – vihāra, Old Turkic vrxar (Gauthiot 1911, 52–59; Gershevitch 1954, 54, compare Sogdian βrywr from Old Iranian *baivar- “10 000”), probably a Sogdian development, on which see also below 4. d, kr’ẓ’kh – kāṣāya (see n. 25). The change of r or l into n has been discussed above (under 2. f).

The Sogdian sound-change of *-aka- stems into /-e/ and *-ākā- into /-ā/, which is evident by the interchange of historical spellings with k and synchronic without k, and by Manichaean and Christian writing, can be also documented in Buddhist loans: ’wp’s’y, ’wβ’s’k – upāsaka; pr’’, pr’kh, Pl. pr’tt’ – paṭāka (see 2. a); one can explain the spellings rš’’k and mytr’k, mytr’y either as non-standard loans or as Sogdian attempts at pseudo historic spelling. The aleph written after k in the borrowings like snk’ – saṃgha (see 2. q) can be explained as an attempt to record articulated /-k/.

In the index below, 55 items, or 18 percent of the material in question, can be considered deviations explainable through Sogdian development without any mediation in transmission.

c. Mediations in Transmission

This problem has been analyzed more than all the above ones, and the role of a Middle Indic source of loanwords and a Parthian, Tocharian, or Chinese transmission has been recognized in a number of words. Some of them will be reviewed below.

d. Parthian and Manichaean Transmission and the Word Buddha

The Indian loans in Parthian and non-Buddhist Sogdian texts were the subject of a detailed article of Nicholas Sims-Williams (1983). He showed that Indian loans started to appear in the earliest texts in Manichaean Parthian and were common in the later texts as well.42 A number of conventions among these forty or so loanwords, such as the simplification of some consonant clusters, the development of kṣ > xš, the spelling of g for Sanskrit y, the change of v into b and of ḍ into l were convincingly ascribed to the North-Western Prakrit (Gāndhārī), while metathesis and the ś > c shift are Parthian (and also Bactrian, see. n. 44) developments. The voicing of postvocalic consonants could have taken place either in Indian or Iranian context (Sims-Williams 1983, 132–35).

Among ten Indian loanwords in Christian Sogdian and forty in Manichaean Sogdian, Sims-Williams identified the ones borrowed via Parthian (’’k’c – ākāśa, ’xšn- – kṣaṇa43, p’š – bhāṣ-, cxš’pt/δ – śikṣapada) and those from Middle Indic, North-Western Prakrit in particular, noting that Old Indian was not its principal source (Sims-Williams 1983, 137). Five loans appear in the Sogdian ‘Ancient letters’, mirroring the trade vocabulary. Only one (dubious, see n. 17) example shows s in place of ś, ṣ, which is typical for most of the Prākrits as well as Pāli, but not the North-Western Prākrit (Gāndhārī). The Khotanese and Tocharian Brāhmī systems also keep s, ś, ṣ distinct, but not Bactrian in Greek script!44

A case to be mentioned here specially is the word for Buddha himself, Sogdian pwt-, rarely pwtt-. In principle, it follows the ‘standard’ rendering of BHS in Sogdian, but a priori it cannot be separated from the form bwt- in Manichaean texts.

Thanks to the work of Iris Colditz on the onomasticon of Iranian Manichaean texts, we have a contextually organized list of appearances of the Buddha in the compositions of the Manichaeans (Colditz 2018, 264–68, No. 170). It appears that the form bwt or bwt is predominant in the corpus: it appears in Manichaean Parthian, Middle Persian (including the translation of Mani’s ‘Book of Giants’), Bactrian and, with final vowel -y, in Sogdian in Manichaean script. The similar form βοτο appears once in inscriptional Bactrian45, Book Pahlavi bwtꞋ and New Persian but “idol” clearly belong here too (Ḥasandūst 1393, 1:408–9). All these forms share the same phonetic value /but/ with the last consonant voiceless and as a rule not geminated.46

Werner Sundermann (1991, 427–30, 2001437–40) analyzed this form in great detail and proposed that the Parthian language (as well as Middle Persian) preferred unvoiced geminate stops after vowels: pattabag “splendor” (< *pati-tapaka-, spelt ptbg), appar “predatory” (< *apa-bar-, spelled ’pr). In a postscript of 2001 (p. 450), he considered the devoicing after simplification of bisyllabic words into monosyllabic: dat < dahat “er gibt,” nēk < nēwak “gut, schön,” Bāt < Bagdāt etc as the “einfachste Erklärung” for bwt. Sundermann’s second explanation (which is accepted by Colditz) does not look satisfactory, since it requires a bisyllabic prototype with final consonant.47

As for the first possibility, some additional comparanda can be supplemented: N. Sims-Williams postulated for Bactrian the rule that the comparative suffix is normally δαρο, but with a final d of an adjective base it turns into ταρο: þαδο “happy” þαταρο “happier” *οαδο “bad” οαταρο “worse, worst” (Sims-Williams and Tucker 2005, 591–92). Parallel cases are observed in Manichaean Western Middle Iranian wtr “worse” and Khotanese battara “less”. Compare also Middle Persian jwtr “different, otherwise” < jwd(y) + dr, kbwtr “pigeon” < *kbwd “blue” + dr, Parthian p’twg “punishment” < *pati-taug, pt’w “stay, suffer” < *pati-taw-. The suffix which is normally spelt -gr, obtains the form -kr after bases ending in -g (as zyntkr “redeemer,” see Durkin-Meisterenst 2014, 168–69). It is true that in the cases listed above historically one or both consonants were voiceless, so wtr e. g. comes from *wata-tara, but still I think that this process, namely the devoicing of postvocalic geminates was the main reason for the peculiar form but in Middle and New Western Iranian, wherefrom it was borrowed into Sogdian.

It is important to notice here that there are no Indic loans that passed through Parthian mediation into Sogdian that are not also documented in Manichaean texts and limited to Buddhist ones. No Buddhist loans with Bactrian mediation have been attested in Sogdian so far, despite the fact of close contacts between the two neighboring regions.48

e. Prakrit Forms in Buddhist Sogdian

For the Buddhist Sogdian texts, Sims-Williams suggests that the majority of loans are of Prakrit origin but notes that “however there are also many spellings which reflect the increasing prestige of Buddhist Sanskrit” (1983, 137). One of the features he considered Prakritic was the rendering of t as δ, thus k’wt’m would be from Sanskrit and k’wδ’m from Prakrit. I do not know cases of δ for Sanskrit t(h) in the beginning of a word, while in postconsonantal position it appears quite often: c’δysm’r – jātismara; c’δyšrwn – Jātiśroṇa; tδ’ktswm – Tathagatasoma. Yoshida noticed that the same convention appears in the name ’’ry’βr’wkδyšβ’r – Āryavalokiteśvara attested only in the late, Tantric sutras that cannot have had a Middle Indic prototype and thinks that the irregularity of δ/t is an inner Sogdian phenomenon (Yoshida 2008, 348 with n. 26). Yutaka Yoshida kindly reminded me of variance of Buddhist mx’pwδy and Manichaean mx’pwtty for Mahāboddhi. One can further adduce the same convention in transcribing Sanskrit invocation: š’kymwn tδδ’kt’w ’r’x’n smyk’ smpwtt – Śākyamumi tathagato arahan (!) samyaksambuddha (Dhyāna 358, MacKenzie 1976, 74–75), showing that this was a perception of Sanskritic postvocal t(h) by the translator.49

Among the Middle Indic loans we should distinguish ones that have Prakritic features surviving in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit as well as occasional shortenings: krkswn(t)[50 – Krakucchanda, Turfan Sanskrit Krakasunda; βcyr- – vajira; perhaps ’yšcyntyt, ’yšc’tyk – icchantika (see n. 10); βr’yšmn – Vaiśramaṇa;51 ’yry’’pt – īryāpatha; p’ytk – pātayantika, pāyattika (if not Tocharian, Yoshida 2008, 340), k’l’y xwt’w – half-translated Kalirājan, Kaliṅgarājan (Khot. Kalä rri, Uyghur Kali bäg and Chinese Jiali 迦利).

What remains are several ‘cultural’ words: k’rt’k52 – gr̥hastha (Khot. ggāṭhaa, Toch. B. kattāke); kr’ẓ’k – kāṣāya, Toch. A kāṣār(i), Niya Prākrit kaṣara, Old Turkic k(’)r’z̤’ (Bailey 1949, 130); pwrsnk – bhikṣusaṃgha with Khotanese bilsaṃgga, Toch A pis-saṅk, Uyghur pursang (Bailey 1967, 242), trywr – tripuṭā, Khotanese ttrola (Maue and Nicholas 1991, 491, n. 38, although one cannot exclude error for *trypr, Manichaean trypl, Brāhmi tr̥phāl – triphala), kwn’k’r – kūṭāgāra (Middle Indic kūḍāgāra, Toch A kurekar etc, Sims-Williams 1983, 137) the names of continents (see n. 56).

Among the Indian loans that are found outside Buddhist texts, the majority come from Middle Indic (Sims-Williams 1983), but some of them show certain older features: Manichaean krm “(evil) action” – karman (Gāndhārī kaṃma but sometimes spelt kram-, karm-, Pāli kamma), Manichaean (?) (’ynt’wk)δyβr’c – Devarājā, r’’t – rājā (Gāndhāri raya, but sometimes spelt raja, Manichaean Middle Persian mh’r’c, Persian rāja).

f. Tocharian

Yoshida (2008, 338–40) noticed several Indic loans in Sogdian that witness vowel and consonant shifts typical for Tocharian B: synt’’p, Sanskrit saindhava, Tocharian B sintāp “stone salt,” tn’pt, Sanskrit dānapati, Tocharian B tanāpate,53 pkc’n, Sanskrit *upagacchana54, Tocharian B pakaccāṃ, A pākäccāṃ; p’ytk – pāyattika, pātayantika, Tocharian B pāyti. The same is supposed for the name kncns’r Sanskrit Kāñcanasāra with Tocharian initial shortening, the name Kañcanasāre is now attested in Tocharian B, and the closely related form is Uyghur kancanasare (Sundermann 2006, 719–20; Yoshida 2019a, 155 with n. 45). Note also ny’ncynt Jñānacinta (name of the monk who translated the Intoxication Sutra from ‘Indian’ into Sogdian) under 2. b., explainable as Middle Indic or Tocharian.

g. Chinese

Despite the fact that Chinese was the direct source of most of the Sogdian Buddhist texts, very few of the Indic loanwords have traces of Chinese mediation. Elio Provasi examined almost 70 loans and compared them to the wide range of Chinese renderings in the Tripiṭaka. He reached the conclusion that Chinese transmission can be detected in very few cases (2013, 280–81).

The phonetics of the Chinese language is fairly distant from Sogdian (like any other any Indo-European) even if in the Tang period it possessed more means to record postvocalic consonants than in modern Mandarin.

Chinese loans in Sogdian texts (such as the names of eras) are often detectable by their ‘atomistic’ outlook: monosyllabic characters are written as separate words that are usually shorter than Sogdian lexemes (see Chinese in Sogdian transcription in Yoshida 2013, 169ff., pl. I).

So, it is easy to see this convention in ’n’wxt’r’ s’m myγ s’m pwδ’y – anuttarasaṃyaksaṃbodhi which passed through Chinese a-nou-duo-luo san-miao san-pu-ti 阿耨多羅三藐三菩提 (EMCh ʔa-nəwh-ta-la sam-mjiaw’ sam-bɔ-dεj; see already Gauthiot and Pelliot 1926, 2:66)55 as compared to ’nwtr’y’n sm(’)yk smpwδ’y (loc. sg. anuttarāyāṃ, see Yoshida 2010, 90), which is attested in other texts and was borrowed from Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit directly. The Chinese mediation here is documented not only with rendering n’wx for nəwh and myγ for mauk, but also with the separate writing of the prefix sam-.

The names of four continents in the Sogdian Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra: cympwδ’y –Jambudvipa, ’wt’nwr – Uttaravati, k’wy’n’ – Godānīya, pwšp’δ’y – Pūrvavideha are difficult and at least two were borrowed from Chinese56: Yanfuti (閻浮提 EMCh jiam-buw-dεj), Yudanyue (欝單越 ʔut-tan-wuat), see extensively Provasi (2013, 217–19, 264–65). The Sogdian forms, however, do not look like Chinese loans; perhaps the translator of the Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra did not know the Indian forms and tried to reconstruct them from the Chinese transcription.57 The same development might be attested in kyδy’ – Jetavana, Chinese Qidia (祇陀, gji-da, see Provasi 2013, 216–17). The form cwδ’yk’ – Jyotiṣka, Chinese Shutiqie (樹提伽, EMCh. ʥuə̆ʼ dεj gɨa), unlike the doublet c’wtyšk’ might be considered Chinese, too (Sims-Williams 1983, 138).

A special case is Sogdian ’’myt’, which is much closer to Chinese Amituo (阿彌陀 ʔa-mji-da) than to Sanskrit Amitābha, Amitāyus (Yoshida 2010, 88–89; Provasi 2013, 199). As for Chinese Amituo, this form did not appear from nowhere, and many suggestions have been made on the shorter Indic prototype;58 the recent suggestion of Jan Nattier (2006, 2007) that a North-Western Prakrit form *Āmitā’a from Amitābha was the source of Lokakṣema’s translation should be mentioned. Moreover, the figure of Amitābha/Amitāyus, and his paradise in Sukhāvatī, has been considered an Iranian plot which was incorporated in Mahāyāna, and the early translators of sūtras on Amitābha were of Parthian, Bactrian, Sogdian59 and Khotanese origin (Scott 1990, 68–71). With these reservations, the Chinese source of Sogdian ’’myt’ cannot be taken for granted.

In the remaining cases, we notice Chinese mediation only in a vowel shift or other minor phonetic features, the transcription appears to be combined from both Indian and Chinese sources: sywpwδ’y, sypwty – Subhūti, Chinese xu-pu-ti (須菩提 EMCh. syou-bou-dei, see Sims-Williams 1983, 138); maybe twr’w(n)[wtn if for Droṇodana, Chinese Tulünuotanna (途慮諾檀那 EMCh dɔ-liə̆h-nak-dan-na’). One can compare pn nyrβ’n parinirvāṇa with Chinese (da)ban nie pan (大般涅槃 EMCh pan-nεt-pan), see Sundermann (2010, 77). The dissimilation of r – r could however appear in an Iranian context as well (under 2. f). Characteristic is pyms’r – Bimbisāra, where the loss of the second b agrees with the Chinese Pingsha (洴沙EMCh. bεjŋ-ʂai/ʂε:), while the second syllable follows Sanskrit well. Sims-Williams (1983, 138; Yoshida 2010, 90) explains Sogdian pk’β’m as a loan from Chinese Pojiafan (婆伽梵 EMCh ba-kia-buamh)60. This term for Buddha is most common in Chinese texts and appears twice in Sogdian (once in the transcription of Skt invocation). Much more common is the epithet βγ’n bxtm, which is similar to other Central Asian traditions: Skt. Devatideva, Gāndhārī devadideva, Khotanese: gyastānu gyastä balysä, Manichaean Parthian bg’n bgdwm, Tocharian B ñakteṃts ñakte pūdñäkte (pañäkte), Uyghur täŋri täŋgrisi burxan.

We have to bear in mind however that many names and technical terms of Chinese Buddhist texts were translated and not transcribed, and in some cases the source of translation is detectable: Sanskrit kleṣa is translated as wytxwy (’t) sryβt’m “suffering (and) pain,” rendering Chinese fannao 煩悩, “vexation – annoyance” (Yoshida 2015, 838) and bodhisattva ’’k’c ptc’’n “concealer of empty space” stands for Chinese Xukongzang, 虚空藏, “empty-space-conceal” (Lurje 2010, 68), while pw px’rš pw nm’n’k βγpyδr’k “prince without retreat without repentance” is translated from Chinese butuizhuan tianti (不退轉天子), “no-retreat-return-god’s-son” and not from Sanskrit Devaputra Avaivartika (Lurje 2010, 312). Eight of 32 names of Buddhas and 16 of 42 names of Bodhisattvas attested in Sogdian are translations and not transcriptions (Lurje 2010, 523–24).

h. Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit as the Source of the Main Body of the Borrowings

Theoretically, in the case of many standard borrowings there is a possibility that they entered Sogdian from a mediating language: e.g. Sogdian knkmwny – BHS Kanakamuni could be borrowed from Tocharian A Kanakamuni, Khotanese Kanakamāmṇa,61 Old Turkic Kanakamuni or Chinese Jianuojiamouni (迦諾迦牟尼, MCh Kia-nak-kia-muw-nri, see Provasi 2013, 218–21). None of these forms is at odds with Sogdian rendering.

In very many other instances, however, these parallel renderings are significantly different from Sogdian. From a general point of view (according to Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion or Occam’s razor), it is advisable, however, to formulate a simple scheme, namely to derive, as much as possible, the material at hand as coming from the single source, and to explain eventual deviations as much as possible as features of the Sogdian language (see 3. a., 3. b). Only if the shape of the loan does not fit this explanation, or if there are significant cultural or philological considerations,62 can we adduce mediation of a tertiary language or tradition (3. c. – 3. g).

The features of Western Iranian, Prakrit, Tocharian, or Chinese transmission of the borrowings in question are present in a limited number of cases, and each one received special attention above.

Returning to the main body of material in standard transmission (in the conspectus), we should evaluate arguments contra ascribing them to any of the neighboring languages of the Buddhist teaching.

These borrowings cannot come from a ‘regular’ Prākrit (or Pāli) since they do not show coincidence of sibilants or simplification of consonant clusters. They cannot come from the Gāndhārī (North-Western Prakrit) because of the preservation of consonant clusters or the absence of lenition of postvocalic consonants (such as j > y). These borrowings did not pass through Parthian or Bactrian because of the different rendering of sibilants (3d, n. 44), the absence of such features as changes in consonant clusters, restoration of v into b, or the fricativization of non-initial stops.

Tocharian A or B cannot be the source of these borrowings because of the absence of vowel quantity and quality shifts, the preservation of -v as -β and not -p, and the few detectable traces of the voiced articulation of stops (see under 2. e.). We do not see in these borrowings the shift of vowels, or the lenitions typical for Khotanese. Uyghur Buddhist texts cannot be the source of these borrowings for obvious chronological grounds, being later than Sogdian ones, let alone the absence of vowel quantity in Uyghur.

We do not see Chinese imprints in vowel change or the loss of postvocalic consonants. There are no cases of syllable-by-syllable spellings save for one example.

In the majority of cases there is no contradiction to the assumption that Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit was the main source of these borrowings (see Yoshida 2009, 291; Provasi 2013, 277).

However, there are three features that are notable exceptions from a straightforward rendering: the transmission of retroflexes as r; the rendering of j as t and the representation of the four postvocalic dentals as t or δ (2c, 2b, 2d). The first is explainable through the absence of retroflexes in Sogdian and the proximity of their articulation place to the sonants l, r. A similar development is visible in Khotanese and Chinese rendering (as in Sogdian βyr’wr’y, Khotanese värūlei, vīrrulai, Chinese Piliule, 毗留勒 EMCh bji-luwh-lək) and in numerous Indic varieties (e. g. Pālī vēḷuriya from vaiḍurya). However, we do not encounter rendering of retroflexes through /l/ in Sogdian. The spelling of j as t /d/ or /t/, as if reducing the affricate /dž/ to its first element, is unusual. One can notice that a voiced affricate did not exist in the Sogdian phonetic system. It is more common to render a foreign /dž/ as c or ž in loanwords.63 For the representation of postvocalic t, th, d, dh as either <t> or <δ> see the discussion under 3. e.

It is evident of course that the words in question were borrowed from the recorded literary language. However, the literary language was pronounced in some way which was more or less close to the written text as we perceive it now. When writing down loanwords, the Sogdian translators, using their own script, had nothing else to do but to record the pronunciation as they heard or learned it, since they could not just copy the writing (as is commonly the case of Tocharian or Khotanese written in Brahmi script). With more experience, however, the translators worked out certain rules of rendering, but one cannot expect a fully systematic scheme.

I suppose that the source of the major part of the borrowings is Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, pronounced in the articulation of Central Asian monks (for none of them Sanskrit was mother tongue!), and recorded according to the perception of foreign sounds by the Sogdians. However, I cannot offer definitive explanations for the peculiarities discussed earlier in this section.

As is well known, for Buddhist loans in various languages there is a feature of reversed stratigraphy: in the earlier records we observe more advanced Middle Indic forms, but in the later texts, more archaic standardized Sanskrit ones are predominant (e. g. Karashima 2006 for Chinese; Salomon 2002 for Gāndhārī; Sims-Williams 1983, 137 for Sogdian).

I propose to explain the predominance of BHS loans in Sogdian as an indication of a relatively late date (after the seventh century) of the bulk of the translations. These loans are thus later than those of the Indian words that entered common Sogdian and Manichaean usages and form an older layer of Indic loans attested in Buddhist texts.

i. Incomprehensible Loans and Distribution of Non-Standard Loanwords within Sogdian Buddhist Texts

Although the great majority of the names in Buddhist Sogdian texts have been explained satisfactorily, there remain some that withstand any attempts. One of them is the name of the fish king in the story in the P2 manuscript, pr’wxy (L). In the Sogdian version of the Śukasūtra (L-93) we encounter a number of incomprehensible names: c’wš’r, k’wšr’t, šwr’t, mx’wr without Indian or any other satisfactory explanation at hand;64 the other names from this text š’ymnkr Kṣemaṃkara (cf. 2. g) and pyms’r Bimbisāra are irregular, too (Rosenberg 1920).

Some other texts are characterized by irregular, somewhat artificial names. One of them is in the Berlin manuscript of the Saṃghāṭasūtra with the names ’ykr’šn, βympx’r, srpšwr, p’tsyn. They have been explained as prakritisms and pseudo-Sanskrit retrospections (Yakubovich and Yoshida 2005; Yakubovich 2013, 42–45).

In the Sogdian Vessantara Jātaka we see many re-etymologized names: mntryh, kršny’n, r’zβwrt. For the name of the main protagonist swδ’’šn foreign explanations, Parthian and Gāndhārī, have been proposed.65

In general, it is safe to assume that non-standard loans appear in certain Buddhist Sogdian texts of rather popular nature, with free narration, lacking footprints of verbatim translation from Chinese, and having even an elaborate style in the case of well-preserved Sogdian Vessantara Jātaka (Yoshida 2015, 840 with literature).

4. Additional Remarks: Some Considerations on Buddhism in Sogdiana and Sogdian Colonies

a. The Perception of the Buddha by Lay Sogdians

The Buddhist Sogdian texts were of course written and read by a limited circle of educated people, principally monks, but rich laymen acted as sponsors. Even if we can presume a relatively high degree of literacy among the Sogdians, the beautiful sūtra script of these texts indicates professional scribes. A large number of Sogdian settlers in the Turfan and Dunhuang area and elsewhere continued to profess their native religion (Grenet and Zhang 1998). Others were Buddhists, Manichaeans, or Christians. The colophons to Sogdian Buddhist texts (P-8 and the Ōtani fragment) as well as the recently discovered Sino-Sogdian funerary inscription (Sims-Williams and Bi 2020) show that within one and the same family of patrons of Buddhism, various persons had Buddhist and non-Buddhist names. In the mentioned epitaph, the An (Bukhara) clan of the sponsor was comprised of possessors of Sogdian names wys’k, w’ywš/wy’ws, srδm’n, ’’δprn, while only the third son of the deceased laywoman had the name pwtyδβ’r “given by Buddha.” Some theophoric names based on Buddha appear in other colophons and inscriptions in Sogdian66, and many more in Chinese documents from the Turfan and Dunhuang areas, which were collected by Yoshida (2017, 47, elaborating earlier versions; see also Wang Ding [王丁] 2019, 192–95). We put them side by side with standard Sogdian theophoric names based on the popular goddess Nanaia and the Moon-god Mākh to show the similarity of the formation.

| Name based on Buddha67 | Meaning | Name based on Nanaia or other deity | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| *pwtyβntk | slave of Buddha | nnyβntk | slave of Nanaia |

| *pwty | (of) Buddha (short name) | nny | (of) Nanaia (short name) |

| pwtyprn68 | glory of Buddha | nnyprn | glory of Nanaia |

| *pwtyβyrt | obtained through Buddha | nny’βy’rt | obtained through Nanaia |

| pwtyδ’yh69 | maidservant of Buddha | nnyδ’yh | maidservant of Nanaia |

| *pwtym’n | resembling Buddha | nnym’nch70 | resembling Nanaia |

| pwty’n71 | boon of Buddha | m’xy’n | boon of Moon-god |

| pwtyδβ’r72 | gift of Buddha | nnyδβ’r | gift of Nanaia |

| pwttδ’s | slave of Buddha (Indic form) | δyβδ’s | slave of god (both parts are Indic) |

This table shows that in the eyes of ordinary lay Sogdians, Buddha was considered a kind of benevolent deity worthy of devotion of a newborn’s name after him. Of course this view was not restricted to Sogdians and such names are attested in many other people’s versions of Buddhism. In many cases, as said, these names are mingled with ones based on Sogdian deities.

b. A Newly Discovered Buddhist Wood-Carving from Panjakent

Much literature has been devoted to the remains of Buddhist art in Sogdiana. The surveys of Tigran Mkrtychev (2002) and Matteo Compareti (2008) are in general up-to-date and reliable sources on this issue. They are now supplemented with the collective volume Religions of Central Asia and Azerbaijan. III. Buddhism (Voyakin et al. 2019). Within the vast range of late antique Sogdian art, the Buddhist remains are very few. Apart from dubious architectural remains and one mural painting from a secondary level in Panjakent, Buddhist artefacts of Sogdiana are limited to a few sculptures in terracotta and metal (the latter being a Chinese import). In some other murals the Buddhist subjects can be considered sources of inspiration for the non-Buddhist messages. On the next pages I add several little known additions to this corpus, one of them being doubtful.

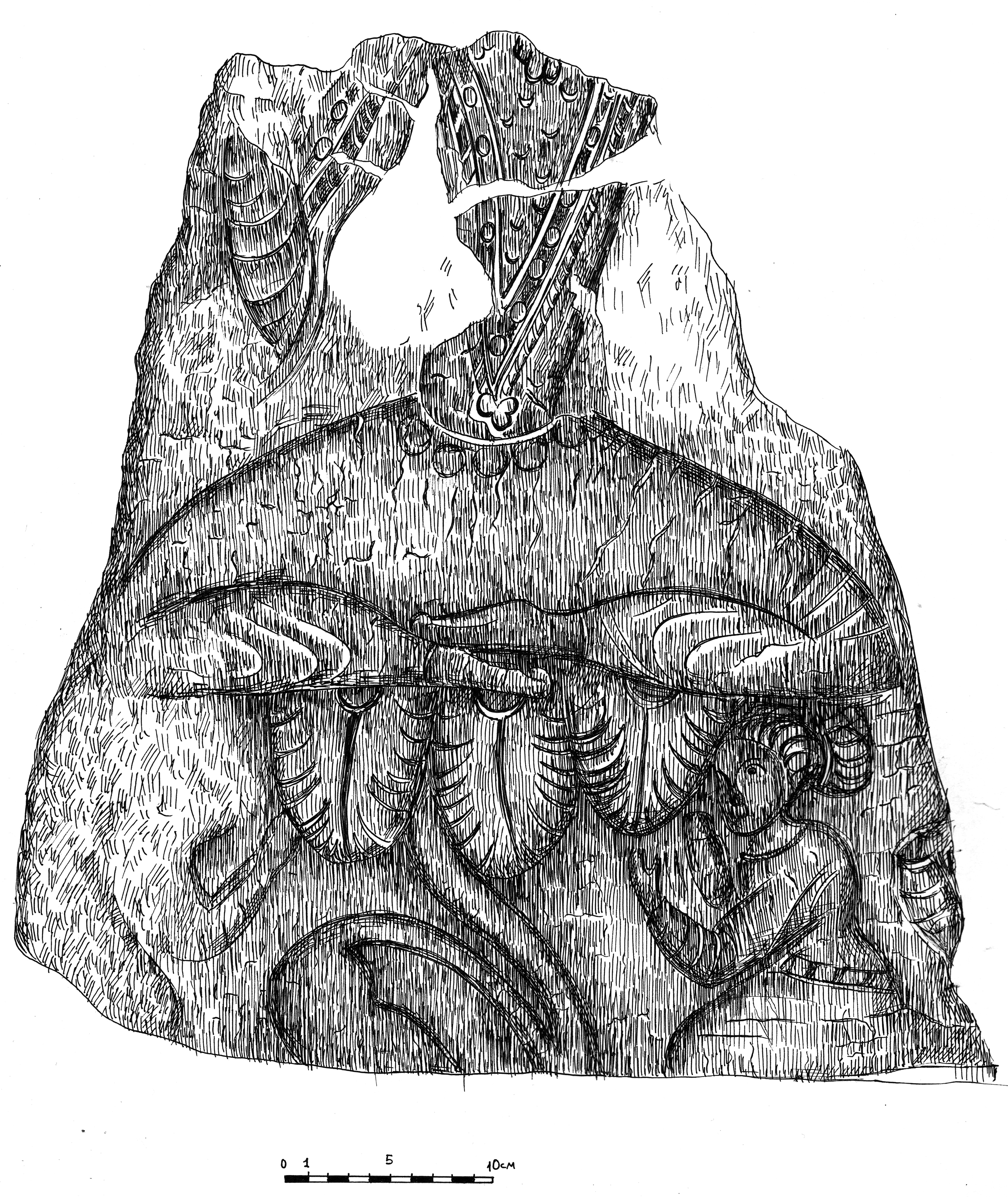

In 2016 the Panjakent expedition found a burned wooden plaque at area XXVI in the eastern block of the city (Kurbanov and Lurje [Lur’e] 2017, fig. 1). The stratigraphic considerations suggest that it was abandoned before the fire of 722 (although the traces of fire in this part of the city are not visible). The semi-oval shape of the plaque 58 x 53 cm, tentatively suggests that once it decorated a lunette above a door. Its sides however did not survive. The central figure (of which the upper quarter is lost) is sitting cross-legged on what one can considered a stylized lotus flower and is raising his right hand. His dress with a triangular collar resembles garments on Panjakent murals and at the same time the ‘Buddha parè’ of Fundukistan in Bactria (e. g. Rowland 1961, 20–24). A smaller-sized donor on bent knees is offering something under the lotus on the right-hand side, and traces of another donor can be detected on the opposite side, and maybe another smaller lotus was further to the right.

This panel is the first detected example of Sogdian wood carving with a Buddhist scene, and probably represents a well-known scene of adoration. The iconography of the panel, however, witnesses Sogdian style (as in the case of painted and terracotta Buddhas from Panjakent): the lotus flower features typically Sogdian petals and the Buddha has thin, elongated legs with small feet, like the characters in the murals of Panjakent and unlike the heavy limbs of early Buddhist style.

c. Sealings from Kafir-Kala and Some New Plastic Finds

The site of Kafir-kala near Samarkand, probably the countryside palace of rulers of Sogdiana, ikhshids, was the spot of numerous finds of well-preserved clay bullae which were discovered in the fire layer of 711. There is a set of offprints of one seal with a figure in full face sitting cross-legged on an ornamented throne (fig. 2); Sogdian inscription appears on two sides of the character. The excavators proposed to see here a depiction of a Buddhist character with the features of Avalokiteśvara, Amitābha, and Padmapāṇi (Berdimuradov et al. 2016; Bogomolov 2019, 339–45). An alternate interpretation may be preferred.

In the inscription the Turkic word x’ttwn “lady, wife of the kaghan” is clearly written in Sogdian script and on its other side there is a less comprehensible Turkic name that includes ’p’ “elder” (Berdimuradov et al. 2016, 53). It is logical to assume that a Khatun was depicted on the seal. Very peculiar is the headgear (or halo, as the authors suggest) with three tips. This kind of headdress is common among the depictions of Old Turkic noble women. The best example is apparently the petroglyph on the lost funerary statue from Kudyrge in Highland Altai, where the lady is depicted as well (Azbelev 2010 with literature; Yatsenko 2013, 75). The double portrait coins from Tashkent oasis are particularly close in date, place, and iconography (Shagalov and Kuznetsov 2006, 75–86, 308). One of the types is inscribed by Ton Yabghu Kaghan, the leader of the Western Turks in the early seventh century. Recently, the observations linking the sealing with noble Turkic ladies were also expressed in Japanese by A. Begmatov (2017, 208–9) and in Uzbek by G. Boboyorov (2020, with an untenable re-reading of the inscription); Yutaka Yoshida informed me that he reached a similar conclusion in an unpublished lecture he held in Stockholm in 2018.

Other features also agree with the interpretation of the seal with Turkic Khatun. Her right hand does not show a vitarka mūdra but holds a small open bowl with two fingers (which was mistaken as a collar), in agreement with stone statues of the Turks (Sher 1963). The crescent to the right is probably the lip of a flask with two handles that can be seen as well. The ribbons from her shoulders must be regarded as a Sasanian cultural practice that was widely followed in Sogdiana. All in all, in my opinion, this seal is an important indication of the role of the Turks in pre-Islamic Sogdiana and the position of noblewomen within their society, but has little to do with Buddhism.

One should add here that a fragment of a bronze figurine of the Buddha enthroned (probably an importation, or rather a somewhat careless recasting of an import) was found recently in Kanka in the Chach (Tashkent) area (Bogomolov and Musakaeva 2020, 288–90). The Buddhist attribution of several minor bronze plastics from Fergana (Bogomolov 2019, 346–48) remains unproven, in my opinion.

d. Toponymic Data

Both Xuanzang and Huichao (see under 1) mentioned one or two Buddhist monasteries in Samarkand, albeit in weak condition. There are very detailed descriptions of early Muslim Samarkand (and other cities of Sogdiana) and among the gates of the city one finds Nawbahār gates. Persian Nawbahār (Nava Vihāra) is the name of a Buddhist monastery in Balkh, famous for its richness, from where the mighty Abbasid viziers of the Barmakī family originated (De la Vaissière 2010, with literature).

The Nawbahār gates were located in the western wall of the city (madīna) of Samarkand and in the eastern wall of the inner suburb (rabaḍ) of Bukhara,73 with two settlements nearby (Bol’shakov 1973, 221–25, 243, 252–3, with literature).

From what is said above one can suppose that the Buddhist monasteries were located near the Nawbahār gates in Samarkand and Bukhara, as in fact was once proposed by W. Barthold (1928, 102 n. 4). Following the same logic, Richard Bulliet (1976) considered all the places named Nawbahār of medieval (in Beihaq in Khorasan and near Rayy close to Tehran) and modern Iran to be places of Buddhist structures.

In later Persian literature, the word Nawbahār had the meaning ‘beauty, beloved’ since the “idol” of the Balkh temple was considered an ideal. It was easily contaminated with Persian naw bahār “early spring,” the time of great outdoor festivities of Iranians. Consequently, not every place called Nawbahār will have a Buddhist origin.

The proof that vihāra is reflected in the Nawbahār of the names of gates of Samarkand and Bukhara can be found in the gate-names of less Persianized cities within the Sogdian sphere of influence in the early Islamic period, where the Sogdian word for vihāra, βrx’r, survived (see Lurje [Lur’e] 2013, 229, 250 n):

Among the gates of Isfījāb city on the Arys river (Sayram in modern southern Kazakhstan) there was a gate which can be reconstructed as Farxār (in Arabic script, f was commonly used for the labiovelar β which did not have a parallel in the Arabic phonetic system).74

Similarly, one of the gates of Binkaθ, the capital of the Tashkent oasis inside the modern city, had the gates which we restore as Farxār from defective writing in the Muslim manuscripts.75

Of course, the etymology of Farxār / modern Parxor in the north-east of historical Bactria (southern Tajikistan, on the Panj river, above the confluence with Vakhsh) is the same.76 Near Parkhor, the late antique and medieval site of Zoli Zard is located (Jakubov and Dovudi 2012). An accidental find of a small limestone head of Buddha from Zoli Zard has been reported recently: https://www.ozodi.org/a/30635395.html (last accessed 03.07.2020); one can recognize Bactrian βοδο in archaic rhombic-shape lapidary script to the right of the face.77

5. Some Conclusions

The analysis above has outlined the conventions that Sogdian Buddhists used to render Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit terms. Although some deviations are attested, the majority of forms follow the conventions regularly. This study shows that more than sixty percent of the almost 300 loanwords into Sogdian which appear only in Buddhist texts follow these conventions, and that the source language is best identified as Buddhist (Hybrid) Sanskrit and not as a Middle Indic vernacular (section 2 with conspectus, 3. h). Among the non-standard loans one can recognize several that originated in Gāndhārī, Tocharian, or Chinese, as well as some Wanderwörter (3. e–g). The loanwords that passed through Parthian are mostly found in Manichaean texts. The few found in Buddhist texts probably include pwt/bwt “Buddha” (3. d). Less than twenty percent of the material show the likely influence of a mediating language. In the equal, if not greater, number of cases the deviations in renderings might be caused by inner-Sogdian developments such as consonant simplifications or re-etymologization (3. a–b).

Although, as it is well known, the major part of Sogdian Buddhist literature was translated from Chinese, we see a quite limited amount of Chinese transmission of Buddhist terms (3. g). Yoshida (2009, 291) and Provasi (2013, 277) already noted that Sogdian monks carefully studied Sanskrit and probably used some word lists for translation similar to the attested Manichaean Middle Persian/Parthian to Sogdian and Sogdian to Uyghur word lists (Provasi 2013, 281). One can add the fragmented Sanskrit-Sogdian bilingual in Brāhmī script on eye diseases (Maue and Nicholas 1991). The Sogdian translations of this fragment follow Sanskrit short phrases or more often individual words one by one, so one can suppose that it was a word list of a physician on a given theme rather than a continuous text with translation. One wonders if similar lists were once used by translators of sūtras. However, one does not need a reference for a correct transcription in every case as the general knowledge of the ultimate source language is often sufficient.78

Given that Chinese was the source of the majority of Sogdian Buddhist translations, it is surprising that only a few cases of Chinese mediation of Indic loans are attested (3. g). However, the translation, rather than the transcription, even among names, constitutes a quarter to one third of the corpus, and in many cases we see footprints of Chinese as the source of this translation.

Turning to irregular, even unexplained transcriptions of Indian names, one can notice that they appear more often among the texts of popular, narrative nature: the Sūkasūtra, the Samghāṭasūtra, and the famous Vessantara Jātaka (3. i). These texts probably appeared before more regular translations, and witness an early form of Sogdian Buddhist literature. We do not know where these texts were composed, in the homeland or in the colonies along the so-called Silk Road.

Traces of Buddhism exist in Sogdiana proper. A recently discovered wooden panel of the worship of Buddha in distinctly Sogdian artistic style from Panjakent can be added to these (4. b). A set of sealings from Kafir-kala near Samarkand recently interpreted as a depiction of Buddha more probably represent a Turkic noble lady, a khatun (4. c). Medieval toponymic data of Sogdiana and adjacent lands indicates the presence of Buddhist monasteries. The place names Naubahār “New Vihāra,” Farkhār (Sogdian βrx’r “Vihara”) are attested in the neighborhood of Samarkand, Bukhara, Binkath in the Tashkent oasis, Isfījāb further north as well on the Panj river to the south-east (4. d). The acquaintance of lay Sogdians with Buddhism, its ‘popular’ version, can be observed not only through the few Buddhist artistic remains from Sogdiana or through the free translations of popular literature but also through the personal names which follow the old Sogdian theophoric models, replacing the name of a deity of the native religion by that of Buddha (4. a).

I hope that the revisited analysis of Buddhist loans in Sogdian as well as additional notes on onomastics, archaeology, and toponymy would throw some light on peculiar aspects of the history of Buddhism in the multilingual and multicultural Central Asia.

6. Index

Lexicographical sources for Sogdian wherefrom one can reach the exact quotations are the following:

-

B Benveniste (1940)

-

G Gharib (1995)

-

L Lurje (2010)

-

MK MacKenzie (1972)

-

P Provasi (2013)

-

R Reck (2016) (with indexes)

-

SW Sims-Williams (1983).

HL abbreviates Hapax legomenon for a word attested only once, IL is for idiolectic forms, the words that appear in one text only but more than once.

a. Standard Borrowings

’’βcy, ’’βycy, ’’βyc – avīci (MK, R) 2. j, 2. s.

’’c’r(’)y – ācārya (B, G, R) 2. b. 2. f.

’’kš’r – akṣara (?, R) 2. q.

’’m(’)wkp’š – Amoghapāśa (L, P) 2. a; 2. i.IL

’’n’k’my – anāgāmin, nom. anāgāmī (R) 2. u. HL

’’n’nt – Ānanda (MK, L, P) 2. q., n. 31

’’ry’βrwkδyšβr – Āryāvalokiteśvara (MK, L). 2. d., 2. i., 3. e.

’’ry’nc – āryaṃ ca (invocation, Yoshida 2010, 90) 2. h. HL

’’s’wr – Asura (G, R) 2. f., 2. k.

’’š’h – Āšā (L) 2. r. HL

’nwtr’y’n sm(’)yk smpwδ’y – anuttarāyāṃ saṃyaksaṃbodhi (Yoshida 2010, 66) 3. g. HL

’psm’r / psm’r – apasmāra (G) 2. i.

’pyδrm – abhidharma (R) 2. i. HL

’r’x’n – arhat (MK) 2. g.; 2. v. HL

’rn’ym – Araṇemi (L, P) 2. m. IL

’wm – oṃ (G) 2. h, 2. n.

’wp’k’ – Upāka (L) 2. k., 2. q. HL

’wrpyrβ’ k’š’yp’ – Urubilvā (Uruvilvā) Kāśyapa (L, P) 2. e., 2. r., n. 19 HL

’wtrkwr – Uttarakuru (P) n. 56 HL

’yry’’pt – īryāpatha (MK). 2. d, 3. e. HL

’yšβr – īśvara (MK) 2. j. IL

’yšcyntyt, ’yšc’tyk – icchantika (R) 2.b., 3. e.

β’swmytr – Vasumitra (L, P) 2. f.

β’yš’ly – Vaiśālī (R) 2. g, 2. m, 2. s. IL

β’yšrβn – Vaiśravaṇa (L, P) 2. c, 2. f., n. 51. HL

βc’ – vacā (Reck and Wilkens 2015, R5) 2. r. HL

βcrkr’wt – Vajragaruḍa (R) 2. c. HL

βcrp’n – Vajrapāṇi (MK, L, R) 2. b. 2. m.

βcyr- – Vaj(i)ra (MK, SW) 3. e., n. 12HL

βrδ’(m)[ – Vardhamānamati (?, R) 2. f. HL

βy’y’m – vyāyāma (Reck and Wilkens 2015, II R6) 2. f. HL

βymrkyrt – Vimalakīrti (L) 2. i. HL

βynwβn – Veṇuvana (P) 2. c. IL

βyny – vinaya (R) 2. f. HL

βyp’š – Vipaśyin (L, P) 2.i, 2. u. HL

βyr’wcn – Vairocana (L) 2. m. HL

βyr’wkt’yn – vilokitāyāṃ (loc., Yoshida 2010, 90) 2. w. HL

βyr’wp’kš/βyrwpkš – Virūpākṣa (L P) 2.i, n. 5.

βyr’wt’kk/βr’wr’k – Virūḍhaka (L, P) 2. a, 2. c.

βyšβ’pw – Viśvabhu (L, P). 2. e. HL

βytty’tr / βyty’δr – vidyādhara (Yoshida 2008, 348). 2. d.

c’δysm’r – Jātismara (MK) 2. e, 3. e. HL

c’δyšrwn – Jātiśroṇa (L) 3. e.

ckkr – cakra (MK) 2. a.

ckkrβrt – cakravartin, nom. cakravartī (MK, L) 2. u.

cnpwδβyp – Jambudvīpa (P) n. 56 HL

cnt – caṇḍ (R, Invocation) 2. m. HL

cntn – candana (MK) 2. d.

cnt’’r – Caṇḍāla (MK) 2. c., 2. i.

cwrypnt’kk – Cūḍā̆panthaka (L) 2. c HL

cynt’(’)mny – cintāmaṇi (MK, P) 2. b.

δ’wt’ – dhūta (MK) 2. k. IL

δy’(’)n(y) – dhyāna (MK) 2. d.

δyβdtt – Devadatta (L) 2. d., 2. m. HL

k’l’y xwt’w – Kalirājan, Kaliṅgarājan (Reck 2013, 186) 3. e. HL

k’r’ynk’ – Kaliṅga (P) 2. i. HL

k’š’yp – Kāśyapa (L P) 2. f., n. 5, n. 32.

k’w šwt – Gocara (MK) 2. n. HL

k’wδ’m / k’wt’m – Gautama (SW, MK, L, P) 2. d., 2. q, 3. e.

k’wšyk’ – kauśika (L, P) 2. n.

k’y’’ k’š’yp’ – Gayā Kāśyapa (L, P) 2. r.

kδp klp krp-h – kalpa (MK) 2. f. , 2. q.

knkmwny – Kanakamuni (L, P) 2. a., 2. i., 3. h. HL

knky(h), knk’ – Gaṅgā (B, L, R) 2. a., 2. p., n. 8

kntrβ – gandharva (MK, P) 2. a

kntyk – ghaṇṭikā (L) 2. c, 2. j, 2. r. HL

kpl[β]st kp’yrβst – Kapilavastu (P, R) 2. j, 2. t.

kr’’m – grāma (B, G) 2. e. IL

kr’wr – Garuḍa (L, P) 2. c. HL

kr’ẉt’ – krodha (R, invocation) 2. d. HL

kr’ytkwt – Gr̥dhakūṭa (P) 2. c. 2. l. HL

krkswn(t)[ – Turfan Sanskrit Krakasunda (L, P) 3. e. HL

krp-h – kalpa (MK) 2. f.

kry’n Kalyaṇa (L) 2. w. HL

kš’try – kṣatriya (R) 2. f. HL

kš’ymnkr – Kṣemaṃkara (L) 2. g., 2. h. HL

kšn, kš’n – kṣaṇa (MK, R) n. 43.

kšytkrp – Kṣitikalpa (L) 2. j. HL

kwm’r- kumara (MK) 2. k.

kwm’rβ’s – Kumāravāsin (L) 2. u. HL

kwmp’yr – kumbhīra (L) 2. j. HL

kwp’yr – Kubera (B, invoc) 2. e. HL

kwsty rs – kusṭha rasa (Reck and Wilkens 2015, R6) n. 30 HL

lnk’ – Laṅkā(vatāra-sūtra) (MK, P, R) 2. f.

m’δ’w – Madu (L) 2. t. HL

m’k(’)t – Magadha (P) 2. i.IL

m’trk š’str – mātr̥kā-śāstra- (R) 2. l. HL

m’ytr – maitrī (or maitrā MK) 2. s. HL

m’ywr – mayūra (L) 2. k.

mncwty – Maṇicūḍa (L) 2. c., 2. q. HL

mntr – mandala, mantra, maṇḍa (MK, R) 2. c, 3. a.

mwkš – mokṣa (MK) 2. n.

mwtr – mudra (B) 2. r. IL

mx’- – mahā 2. g.

mx’’k’y – mahākāye (R, invocation) 2. m. HL

mx’k’š’yp’ Mahākāśyapa – *(L, P) 2. q. HL

mx’kp(’)yn – Mahākapphiṇa (L) 2. e. IL

mx’m’yh – mahāmāyā (L, P) 2. r.

mx’pwδy – mahābodhi (B) 3. e., compare Manich mx’pwtty

mx’r’c – mahārāja (MK) 2. g.

mx’stβ – mahasattva (MK) 2. g.

mx’tyβ – mahādeva (B) 2. d. HL

mx’y’n[y] – Mahāyana (R) 2. d.

mx’yšβr – Maheśvara (MK) 2. g.IL

n’r(kr’k) – nāṭa (Gershevitch 1954, 54) 2. c. HL

n’t’y k’š’yp’ – Nadī Kāśyapa (L, P) 2. d. HL

n’ywt – nayuta (R No. 670) 2. k. HL

nymyš – nimeṣa (Reck and Wilkens 2015, V6) 2. m. HL

nyrβ’n – nirvāṇa (MK) 2. c.

nysrky – niḥsargika, (R) 2. a. HL

p’r’wr – balūla (? L) 2. f. HL

p’rmyt – pāramīta (Reck 2013) 2. d. HL

p’tr – pātra (R) 2. i. HL

pk’’β’n (invocation)* – Bhagavant (MK) 2. h, n. 35 HL

pr’m(’)n – brāhmaṇa (MK, R) 2. g.

pr’pt – Prāpta (L) 2. e. HL

pr’tny’p’rmyt, prtnyh p’rmyt – prajñāpāramitā (MK). 2. b.

pr’ttymwkš – prā̆timokṣa (MK, R) 2. d.

pr’xmn – brāhmaṇa (MK, R) 2. g.

pr’yt – preta (MK) 2. m.

prδwk’ – paraloka (B) 2. f.

prt’ykpwt(t) – pratyekabuddha (MK, R). 2. f.

ptrp’r – Bhadrapāla (L) 2. e. HL

ptr klp(-) – bhadrakalpa (MK) 2. f. IL

pt(t)r – pattra (R) 2. d.

pwδ’y – bodhi (MK) n. 60

pwntr’yk – puṇḍarika (R) 2. c.

pwr’wš – Puruṣa (L) 2. k. HL

(p)wrβ’š’(t) – Pūrvāṣāḍhā (R) 2. g. HL

pwrn’y – Pūraṇa (Yoshida 2019a, 148). 2. q. HL

pwšpcwty – *Puṣpacūḍa (L) 2. k. HL

pwt(’)kš(’)ytr – Buddhakṣetra (MK) 2. m.

pwtr’ky (obl)* – Potalaka (P) 2. q. HL

pwt’y mntr- bodhimaṇḍa (R) 3. n. 60.

ṗykšw, pykšw – bhikṣu (Sims-Williams apud MacKenzie 1976, ii 9, note. 37, L sv. kry’n) 2. e.

pyntp’tw – piṇḍapāta (MK) n. 30 HL.

r’ckr(’)y (obl) – Rājagr̥ha (P) 2. g., 2. l.

r’xw – Rāhu (L, P) 2. t. IL

rkš, rkkš – rakṣā (MK) 2. a., 2. f.

rnk’/lnk’ – Laṅkā (MK P R) 2. a, 2. f.

rs – rasa (Reck and Wilkens 2015, R5) n. 30. HL

rtncwty – Ratnacūda (L) 2. q. HL

rtnkyrt – Ratnakīrti (L) 2. s. HL

rtnšykynn – Ratnaśikhin (L) 2. u. HL

rwk’yntr r’t – Lokendra rājan (MK, L). 2. b, 2. u. HL

rwkδ’t – lokadhātu (MK) 2. f., 2. t.

s’δw s’δw – sadhu sadhu (MK) 2. d. 2. t

s’l’ ryzkry xwβw – Sāla-Īśvararāja (R) 2. q. HL

sm’ntpttr – Samantabhadra (L) 3 b. HL

smyk’ smpwtt – samyaksaṃbuddha (MK) 2. h., 2. q.

snk’ – saṃgha (MK) 2. h., 2. q. 3. a, 3. b.

snk’’βšyš – Saṃghāvaśeṣa (Yoshida 2000, 287, 3) 2. g. HL

snkr’m – saṃghārāma (MK) 2. h.

sntwšʾyt Santuṣita (R) 2. g. HL

srβ’’rtt sytt – Sarvārthasiddha (L) 2. d, n. 33 HL

srβ’stβ’t – sarvāstivāda (R) 2. g. HL

srβšwr – Sarvaśūra (L) 2. f.

stwl(’nc) – Sthūlā(tyaya) (R) 2. f. HL

swk’βty – Sukhāvatī (MK) 2. s. HL

swβrncwty – Suvarnacūda (L) 3. q. HL

swpwδy – Subhūti (R) 2. s. HL

swpwty – Subhūti (R, transcription of Chinese) 2. s. HL

swttr – sūtra (MK) 3. a.

swttršny – Sudarśaṇa (L, P) 2. q.

syt(t) – siddhi (MK, R) 2. d., 2. s.

š’ky – Śākya (L, P) 2. g. HL

š’kymwn – Śākyamuni (MK, L, P) 3. b., 3. e. attestation in Manich. is dubious

š’r(’)ypwtr – Śāriputra (L, P) 2. f.

š’str – śāstra (R, Livshits 2008, 336, 5) 2. g.

šβ’kwšh, šβk’wš, šβk’wšh, šβkwš, šβkwšh, šyβkwš, šyβkwšh – Śivaghoṣā (P) 2. r. IL

šβ’y – Śivi (L, P) 2. s., n. 19 IL

škš’pt/δ – śikṣapada (MK) n. 9.

šl’wk, šr’wk(’) – śloka (MK). 2. q, n. 7.

šr’’βk – śrāvaka (MK) 2. i. HL

šr’ykwty – Śrīkūṭa (SW apud L) 2. c. HL

šrmn – śramana (SW) n. 20 IL

šyβkwšh > šβ’kwšh

šyky – Śikhin (L, P) 2. u. HL

t’rn’y – dhāraṇī (MK) 2. d, 2. s.

tδ’ktswm – Tathagatasoma (L) 3. e. HL (PN)