Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān in Islamic Arabic Literature until 1400 AD

The last king of Ḥimyar, Yūsuf Asʾar Yathʾar (reign 522–525 AD), is famously known as the Jewish persecutor of the Christians of South Arabia, most notably the ones in Najrān, who were martyred in the autumn of 523 AD. In Islamic literature, the king was known as Dhū Nuwās and became associated with the aṣḥāb al-ukhdūd “the People of the Trench” mentioned in Q85:4–10. The article surveys the Islamic Arabic literature about Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān from its beginnings until the fifteenth century AD, and tries to establish literary relationships between the sources as well as literary typologies in the rich and overwhelming literature. Throughout the survey, attention is given to how different Muslim writers have dealt with the Pre-Islamic ‘Abrahamitic’ past of Arabia in forming the Islamic narrative of history.

Martyrs of Najrān, Dhū Nuwās, Ḥimyar, People of the Trench, Qurʾānic Exegesis, Islamic historiography, Muslim attitudes towards Pre-Islamic Jews and Christians

The Martyrs of Najrān and Islam—An Introduction

A century before Muḥammad and his community of monotheists migrated from Mecca to Yathrib, at the oasis of Najrān in Southern Arabia, a group of Christians, which had been there since around 450 AD, came into conflict with the Ḥimyarite rulers to the South. In 522, the Ḥimyarite king Yūsuf Asʾar Yathʾar, later known as Dhū Nuwās in the Islamic tradition, initiated military campaigns against those Axumites who were in Yemen and their Ḥimyarite Christian allies who resided in his kingdom and beyond.1 The campaigns culminated with the siege of Najrān in 523 and the successive executions of a large number of inhabitants, among whom the city’s Christian nobility played an important role in the diverse hagiographical literature that was produced in the aftermath of the events.2 The historical circumstances and the cause(s) of Yūsuf’s aggressions against South Arabian Christians have been explained in different ways,3 but one of the most prominent is the explanation of differing religious, and by extension political, sympathies—Yūsuf was Jewish along with generations of rulers at the Ḥimyarite court before him.4 It is exactly this religious difference which the Christian hagiographers latched onto, and they made it the prime motivation of Yūsuf for executing the Christians. With the hagiographical embellishments with which the tradition eventually was adorned, the Christian writers successfully rebooted a mental software of martyrdom and persecution, which had been without major updates since Diocletian and Galerius.

This interesting fact, that a Jewish king in South Arabia had persecuted Christians in Pre-Islamic times, also caught the imagination of Muslim writers, but for different reasons. From very early on in the development of Qurʾānic exegesis, the events of the persecution and massacre of the Christians of Najrān were associated with the enigmatic sentences in Q85:4–10, here cited from Arberry’s translation:

Slain were the Men of the Pit, the fire abounding in fuel, when they were seated over it and were themselves witnesses of what they did with the believers. They took revenge on them only because they believed in the All-mighty, the All-laudable, God to whom belongs the Kingdom of the heavens and the earth, and God is Witness over everything. Those who persecute the believers, men and women, and then have not repented, there awaits them the chastisement of Gehenna, and there awaits them the chastisement of the burning.

The episode of the massacre at Najrān came to be reported as an interpretative frame of these Qurʾānic verses in most works of tafsīr (and often the only interpretative frame mentioned). In this sense, the episode was also included in pieces of historiographical literature, such as the Sīra,5 as a sabab al-nuzūl, contextualizing the Qurʾān and thereby introducing these Christian Martyrs to the divine prophetical narrative of mainstream Islam. Another reason for the interest in the Christian community of Najrān was that historians of Yemeni descent had developed a particularly strong sense of pride, often coupled with an antiquarian interest in the glorious past of the South Arabian people.6 They compiled long lists of dynastic rulers from the different Yemeni kingdoms, and collected native legends and poetry.7 In the catalogues on the kings of Ḥimyar, Dhū Nuwās is always mentioned as the ṣāḥib al-ukhdūd, and his involvement with Najrān is recurrent in all the entries on him.

The Islamic incorporation of the narratives in question has for a long time interested Western scholars as sources for historical reconstruction of the Ḥimyarite-Axumite conflict, as sources for the history of monotheism in South Arabia,8 or as comparative literary material preserving older Christian hagiographical and historical narratives.9 This research has been fruitful, and especially the research done since 2010 has brought many new insights and gradually introduced different sources to the discussion. Often, however, historians writing about late antique South Arabia refer to the “Islamic tradition” en bloc while referring to relevant individual Christian texts. There can be two reasons for this: either the Islamic texts dealing with the events in question really are a harmonious lot, or the amount of relevant material can seem quite overwhelming to those not Islamicists and Arabicists. It seems that Ibn Hishām’s Sīra and al-Ṭabarī’s Taʾrīkh are the main sources when the “Islamic tradition” of the Martyrs of Najrān and Dhū Nuwās are referred to. Though these two are very important sources and two of the most voluminous, they are also the most well-known and readily accessible, which potentially can bias the view of the “Islamic tradition.” The historical reconstruction of Dhū Nuwās’ reign (Yūsuf Asʾar Yathʾar) and his involvement in Najrān have been attempted by Christian Robin (2008, 2010, 2012), using contemporary South Arabian inscriptions as well as Christian and Islamic sources with great success. What follows, on the other hand, is an attempt at presenting the “Islamic tradition” of Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān in its different manifestations.

The purpose of the present article is twofold: Firstly, to gather the Islamic material that pertains to Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān,10 and, when possible, (try) to establish the literary relationships between the different Arabic sources. I have been as comprehensive as possible within the limits of this contribution.11 I hope that this literary investigation will help to shed light on less studied but interesting sources, thereby providing a more diverse picture of the Islamic tradition on this historical episode. Thus, the article is also meant as a go-to catalogue of Islamic sources to Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān. Secondly, these texts are great examples of the different ways Muslim authors and compilers have dealt with Jews and Christians of pre-Islamic history, and the article will highlight how different narratives and agendas have moulded the stories to serve these narratives.

An Overview of the Sources

The present article is the result of readings and analyses of 37 Islamic Arabic sources dealing with the topic in question. They cover many of the genres within Classical Arabic prose: historiography, Qurʾānic exegesis, ḥadīth, commentary on poetry, dictionaries of geography and ethnography, and adab. The scope of the sources ranges from one sentence (Abū l-Fidāʾ) to whole sections consisting of around ten pages of edited Arabic prose (al-Ṭabarī). The sources that have been considered cover the whole of Classical Islamic literature from the beginning of the eighth century (Mujāhid (d. 722), al-Ḍaḥḥāk (d. 723)) to the fifteenth century (Ibn Khaldūn (d. 1406)). In the bibliography, the reader will find an alphabetically arranged list of all the sources and the editions used. References to the relevant sections in each work are found in sharp brackets, as well as throughout the article.12 Unless stated otherwise, all translations within this contribution are my own. For the sake of overview, I have divided the sources into five groups:

- The earliest tafsīr-traditions

Tafsīr-traditions attributed to Ibn ʿAbbās

al-Ḍaḥḥāk

Muqātil and Mujāhid

The Ibn Isḥāq-tradition

The Ibn al-Kalbī-tradition

- Miscellanous historiographical sources

al-Dīnawarī

al-Hamdānī

al-Maqdisī

- The mainstream tafsīr-tradition

The Ṣuhayb recension

The Ibn ʿAbbās recension

Three of these groups (2, 3 and 5) have been established on the grounds of external information, explicit references to sources, and especially of internal textual relationships, i.e. texts transmitting the same textual tradition, albeit with different degrees of variation. Groups 1 (early tafsīr) and 4 (historiographies) contain texts which could not easily be directly associated with a specific tradition, or are representative of (otherwise lost) traditions. The traditions of these five groups are by no means isolated. On the contrary, they are all interlinked in some way.

The Earliest tafsīr Traditions

While the story about Q85:4–10, found most frequently in works of tafsīr, is about a young boy (ghulām) and a monk in Najrān, to which we will return, the earliest mufassirūn did not possess the ballast of a long established tradition, and they often offer snapshots of Qurʾānic interpretation in a time before conformity and traditionalism. These commentaries are often concise and implicit, and are therefore often difficult to understand. Whatever the Qurʾān was originally referencing to its intended audience,13 it is clear from the tafsīr-traditions here, however, that Yemen and Najrān were associated with the aṣḥāb al-ukhdūd mentioned in Q85:4–10 from very early on.

Tafsīr Traditions Attributed to Ibn ʿAbbās

Traditions attributed to ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbbās (d. 687) deserve some discussion, despite the controversy that surrounds this figure in the scholarship of ḥadīth and tafsīr.14 The Tafsīr of Ibn Wahab al-Dīnawarī (d. 920)15 transmits interpretations of Sūrat al-Burūj on the authority of Ibn ʿAbbās, which are identical with the equivalent passages in the Tanwīr al-Miqbās min Tafsīr Ibn ʿAbbās.16 Some interesting observations will suffice: this is the only tradition of tafsīr dealt with here which does not explicitly mention the people of Najrān in connection with Q85:4, i.e. the aṣḥāb al-ukhdūd “the People of the Trench.” The people of the Trench is described rather generically as a “group of believers (qawm min al-muʾminīn), whom the unbelievers (al-kuffār) killed by means of fire fueled by naphtha, pitch and firewood.” There is no mention of Christianity or Judaism, and the Qurʾānic dichotomy between “believers” and “unbelievers” are the only words of religious implications used by ‘Ibn ʿAbbās.’ In the commentary of Q85:10, however, a group from Najrān is mentioned, but as the perpetrators of the believers:

It is said: In this life, where God burned with fire those who were a group from Najrān, some say from the people of Mosul, they seized a group of believers, torturing and killing them with fire in order that they convert to their religion (dīnihum). Their king was named Yūsuf, some say Dhū al-Nuwās. So he (God) mentioned the believers, who did not turn away from the belief in face of their torture.

From the presence of the name Yūsuf, it becomes clear that the group of believers is the Martyrs of Najrān. A number of places this text diverts from the main narrative of the tradition, which we will encounter later in the Classical literature. This could suggest that the tafsīr tradition is from the time before the tradition about the king of Ḥimyar, Dhū Nuwās and from before his persecution of Christians became common knowledge (mainly informed by Wahb ibn Munabbih (d. 728/732)). First, the mufassir does not explain the obscure word ukhdūd, which subsequent exegetes explain as a trench, or ditch, that was dug and filled with fire for the Christians, but he remains vague (or ignorant?) about the specific circumstances. Secondly, the victims are not from ‘the people of Najrān’ (ahl Najrān), but a group of believers who were burned by a group from Najrān (or Mosul17), who in turn was burned by God as punishment. The mufassir knows Yūsuf by the name of Dhū al-Nuwās, to my knowledge not attested anywhere else, and he is the king of the group of Najrān (see also the tafsīr of Muqātil), not Ḥimyar. These factors point to an early dating of this tafsīr tradition of Q85, which also share some features with al-Ḍaḥḥāk and Muqātil, even if the Tafsīr as a whole should be dated to the ninth or tenth century. It is of course impossible to determine if it really is the work of Ibn ʿAbbās, but it cannot be rejected based on this case reading of commentaries of Q85:4 and 10.

al-Ḍaḥḥāk

Al-Ḍaḥḥāk ibn Muzāḥim (d. 723) was part of the first generation of Muslim exegetes and is quoted by numerous later mufassirūn.18 It is unclear whether he himself actually produced a coherent work of tafsīr, but the traditions attributed to him through quotations in later works have been gathered into a two-volume ‘Tafsīr’ by Muḥammad Shukrī Aḥmad al-Zāwiyyatī. Three different quotations in this work are of interest to us, all commenting on Q85:4.19 Quotations 2878 and 2879 give two very similar accounts of the aṣḥāb al-ukhdūd, here 287820: “they allege that the People of the Trench are from the banū Isrāʾīl. They seized men and women and dug a trench for them. Then they lit fires in it, put the believers (al-muʾminīn) in front of it, and said: ‘you shall apostatize (takfirūna) or we will throw you into the fire!.’” Quotation 2879 does not identify the People of the Trench with banū Isrāʾīl, but simple states that “they are a group, who made a trench in the ground.” The ‘believers’ of quotation 2878 are here called “the people of Islam (ahl al-islām)” and are thus exhorted: “deny God (ikfirū bi-llāh) and adhere to our religion!” As we are told, the ‘people of Islam’ preferred fire to unbelief (al-kufr) and were thrown into the fire. Quotation 2880 again identifies the People of the Trench, who now “were among the Christians of Yemen (kānū min naṣārā al-Yaman),” and tells us the event happened forty years prior to the call of Muḥammad (mabʿath rasūl Allāh). In quotations 2878–9, al-Ḍaḥḥāk identifies the “People of the Trench” as the perpetrators, not the victims, and if these three traditions attributed to al-Ḍaḥḥāk should be read harmoniously, then the Christians, who may or may not be thought of as part of banū Isrāʾīl, are here thought of as the perpetrators. The victims, however, are all described with typical Islamic lingo, which was a common way for Muslim authors to ‘appropriate’ pious individuals (often from the ‘People of the Book’) who lived in Pre-Islamic times. This will become a recurrent theme in this article.

Muqātil and Mujāhid

Muqātil ibn Sulaymān’s (d. 767) Tafsīr is the oldest extant exegetical work that comments on the Qurʾān in its entirety.21 He is known to have relied on Christian and Jewish informants in his work, which thus contains a great amount of isrāʾīliyyāt.22 In commenting Q85:4, he identifies the aṣḥāb al-ukhdūd with “Yūsuf ibn Dhū Nuwās from the people of Najrān (min ahl Najrān).”23 In agreement with both al-Ḍaḥḥāk and the version attributed to Ibn ʿAbbās, the word aṣḥāb is interpreted as the perpetrators, and these are identified with a group or an individual from Najrān.24 As was also the case with ‘Ibn ʿAbbās,’ Muqātil gives a variant name of Yūsuf, namely ‘son of Dhū Nuwās.’ In Muqātil’s version, Yūsuf had dug a furrow and burned in it anyone who professed monotheism (man takallama […] bi-l-tawḥīd). We are told that there were eighty believing men and nine women among his people, whom he ordered to abandon Islam (an yartaddū ʿan al-islām). As the believers deny this, Yūsuf begins to throw them, one after another, into the fire

until a woman passed by with her young boy suckling. When the woman looked at her son, she feared for him, so she turned around. They urged her to apostatize, but she refused. So they beat her until she turned back around, but she kept turning around fearing (for her son) until the boy spoke and said to her: ‘Mother, before you is a fire, which will never be extinguished!’ When she heard the words of the infant, she was prepared (uḥḍirat) to throw herself into the fire. God, mighty and great, then placed their souls in heaven (al-janna).25

A similar story to the one of Muqātil is found in the Tafsīr of Mujāhid ibn Jabr (d. 722) collected by Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Salām Abū al-Nīl (ed. 1989):

The people of the Trench dug a trench and filled it with fire. They threw into it anyone who believed in God, and let everyone who apostatized be. They had thrown more than eighty believers (in the fire), when they came upon an old woman and her son who followed her, a young boy. When she saw how the fire consumed them, she became anxious and said: ‘O my son, do you not see (it)?’ Her son said to her: ‘Mother, carry on, don’t be a hypocrite!’ So she carried on and her son jumped in after her.26

This story does not give any kind of contextual information. No location, names of persons or religious affiliation is mentioned. In the subsequent quotation, however, Mujāhid says that the ukhdūd was a chasm (shaqq) in the ground in Najrān, in which they used to torture people.27

The story about the woman and her son is interesting, and we will encounter it throughout many of the sources,28 but it will suffice for the time being to notice that there is still no mention of Jews or Christians (with the exception of al-Ḍaḥḥāk’s quotation 2880). Muqātil and Mujāhid likewise tell this story through the Qurʾānic religious nomenclature of believers, unbelievers, and Islam, as is to be expected from the specific genre.

The Kings of Ḥimyar Tradition

The following six texts transmit a tradition which ultimately derives from a very early work of Yemeni origin about the kings of Ḥimyar. This has often been attributed to Wahb ibn Munabbih (d. 728/732), given that a work of this kind is attributed to Wahb by different later Muslim biographers, and that we have a work by Ibn Hishām (d. 833) called Kitāb al-tījān fī mulūk Ḥimyar, in which he transmits a tradition or work by Wahb. There is evidence to suggest, however, that Kitāb al-tījān is a compilation of two works, one by Wahb and a perhaps earlier anonymous work on the kings of Ḥimyar, but the exact relationship between Wahb and Kitāb al-tījān is far from explained.29 This tradition has been very important for how later Muslim historians arranged their works, e.g., Ibn Isḥāq’s Sīrat Rasul Allāh,30 and a significant number of subsequent works contains this tradition. Therefore, I here give a translation of the relevant passage in Ibn Hishām’s Kitāb al-tījān:

Dhū Nuwās Zurʿa ibn Tubbān Asʿad, a crowned king.

When it reached Ḥimyar what Dhū Nuwās had done, they said to him: “No one is more fitting to be our king than you, since you have delivered us from this evil!” He was the last of the kings of Ḥimyar and he remained in power for some time. He was the master of the Trench (ṣāḥib al-ukhdūd), whom God has mentioned in the Qurʾān, that is, it had reached him [i.e., Dhū Nuwās] concerning the people of Najrān that a man from the house of Jafna of Ghassān had come to them and brought them to the religion of Christianity (fa-raddahum ilā dīni l-naṣrāniyya). So Dhū Nuwās himself travelled towards them until [he stopped and] dug trenches in the ground and filled them with fire. He then left everyone alone who followed him in terms of his religion, but threw into [the fire] anyone who kept adhering to Christianity. [So he did] until he brought forward a woman with a young boy of seven months. Her son said to her: ‘Mother, carry out your religion! It is certainly fire, but there will be no fire after this one!’ A man called Dhū Thaʿlabān by the name of Daws passed by the woman and her son in the fire. He travelled by sea to the king of Abyssinia and told him about what Dhū Nuwās had done to the people of his religion. Then the king of Abyssinia wrote to Qayṣar [i.e., the Byzantine Emperor], informing him about what Dhū Nuwās had done, and asking him permission to set out towards Yemen. [The Emperor] wrote to him with his order to march against [Yemen]: He told him that he should conquer it and commanded him to entrust Dhū Thaʿlabān with the command over his people, and to stay in Yemen with those who were with him. The king of Abyssinia advanced with 70.000 men, so Dhū Nuwās rallied against them and fought with them, but they defeated him and killed many of his people. Defeated, he ran out towards the sea, while they were right behind him. He jumped into it and drowned together with those of his people who were with him. The reign of Dhū Nuwās lasted for 38 years.31

This passage is the prose part of the entry on Dhū Nuwās in a list of the kings of Ḥimyar and is of the historical or annalistic genre. Dhū Nuwās is preceded by the wicked king, Lakhīʿa ibn Yanūf (dhū Shanātir), whom Dhū Nuwās kills, which is why the people appoint him as their king, and he is followed by king Abraha. Unlike the tafsīr pieces presented so far, the Kitāb al-tījān is interested in specifics—in who, where, what, and when. Even though the association with the Qurʾān is acknowledged, it is not interested in Qurʾānic matters but in the information and legends of the Ḥimyaritic king in question. There is no attempt to appropriate the Martyrs of Najrān as ‘proto-Muslims’ or as generic ‘believers.’ They are explicitly Christians, and the origin of this Christianity is given as well: A man from the house of Jafna of Ghassān, i.e., the Arab vassal state of the Byzantine Empire. This tradition seems not to have received much attention in previous studies on the Christianization of South Arabia, which have been primarily concerned with the stories of Faymiyūn and ʿAbd Allāh al-Thāmir, dealt with below. These, of course, give actual accounts of Christianization, and there is therefore much more to say about them, but it seems strange not to include this source, given the fact that it is old, and that it mentions a specific tribal (and by implication geographical, political and ecclesiastical) affiliation of the missionary. Curiously, there is no mention of Judaism or any other specific religion of Dhū Nuwās. It simply says that the conversions to Christianity in Najrān were the reason for his aggressive actions against the city, and that he would leave everyone who followed him in terms of his religion (ʿalā dīnihi) alone. It is difficult to determine whether this silence on the specific religion is due to an intentional ambiguity on the author’s or Ibn Hishām’s part, or due to the poor editorial condition in which we have this text. Yet again, the story of the woman and her son occurs, this time in a slightly more elliptic version.

Ibn Qutayba (d. 889) has transmitted large parts of this tradition of the Ḥimyaritic kings in his Kitāb al-maʿārif, in which he also states that he used a work by Wahb ibn Munabbih called ‘The Book on the Beginnings and the Stories of the Prophets.’32 The section on Dhū Nuwās follows Kitāb al-tījān relatively closely,33 but there are some interesting differences. Beside small textual changes, which I will not comment on here, there are minor differences in content. Ibn Qutayba states explicitly that Dhū Nuwās was an adherent of Judaism. The missionary is not said to come from the house of Jafna, but Ibn Qutayba states that “he came to them prior to the house of Jafna, the kings of Ghassān” (atāhum min qablu āl Jafna mulūk Ghassān). The whole sequence of Dhū Thaʿlabān and the royal correspondence is almost the same as in Ibn Hishām, but after the death of Dhū Nuwās, Ibn Qutayba gives a short “coda” comprising the reign of Dhū Jadan who suffers the exact same fate as his predecessor. The duration of the reign of Dhū Nuwās is given as 68 years, but it is unclear whether this includes the reign of Dhū Jadan or not.

Unlike Ibn Hishām and Ibn Qutayba, al-Masʿūdī (d. 956), in his Murūj al-dhahab, does not present the section on Dhū Nuwās as part of a list of Ḥimyaritic kings. Rather, he has extracted this passage either from a work by Wahb, whom he lists as an authority at certain places in the chapter, or from Ibn Qutayba, and inserted it into a chapter (chapter 6) on “the people of the interval (ahl al-fatra) between Christ and Muḥammad,” which is a catalogue of pre-Islamic monotheists. Al-Masʿūdī is in this passage not interested in Dhū Nuwās, but in the ‘people of the Trench,’34 and it is clear that he does not have the same historical/annalistic aims with this passage as his source(s).35 Therefore, he has to massage the text in certain places with a prophetic reading. First of all, al-Masʿūdī has omitted any mention of a missionary. Furthermore, he has replaced the word ‘Christianity’ (al-naṣrāniyya) with the euphemism ‘the religion of Christ’ (dīn al-Masīḥ), which is often used by Muslim authors to refer to the ‘uncorrupted’ form of monotheism which Jesus brought to his people, who subsequently altered it into the schismatic religion of reality which Muslims refer to as ‘Christianity.’ It is especially with respect to the woman and her son that al-Masʿūdī’s interpretative biases come to the foreground. While the premature linguistic abilities of the seven months-old boy are taken for granted by Ibn Hishām and Ibn Qutayba, al-Masʿūdī explains it as a result of divine intervention: “[…] as (the woman) came closer to the fire, she became anxious. So God endowed the infant with speech (fa-anṭaqa Allāh al-ṭifl) and it said […]” It is also worth noting that instead of ‘a small boy’ (ṣabī), as in the two earlier works, al-Masʿūdī has the word ‘infant’ (ṭifl) making the miracle even greater.36 There can apparently be no room for misunderstanding or ambiguity for al-Masʿūdī, since he makes the following statement after the woman and her son have been thrown into the fire: “the two of them were monotheistic believers, not adherents of the Christianity of that time” (wa-kānā37 muʾminayni muwaḥḥidayni lā ʿalā dīn al-naṣrāniyya fī hādhā l-waqt). The sequence of the royal correspondence is different from the two sources mentioned so far. In Ibn Hishām and Ibn Qutayba, Dhū Thaʿlabān first travels to the king of Abyssinia, who then writes to the Byzantine Emperor for permission to intervene. In Murūj al-dhahab, Dhū Thaʿlabān goes straight to the Emperor, king of the Byzantines (Qayṣar malik al-Rūm), as he is called, who then sends his request forward to the king of Abyssinia, now called by his Ethiopian title, the Negus (al-Najāshī), whose kingdom was closer to the area of conflict. This difference is probably due to an influence from the Ibn Isḥāq tradition, in which Dhū Thaʿlabān first travels to the Emperor (Qayṣar ṣāḥib al-Rūm38), who refers him to the Negus, because of the distance between his kingdom and Yemen. Al-Masʿūdī refers, in connection to this, to two of his own earlier works,39 where he dealt with this episode in further detail, as well as the section on the kings of Yemen later in the Murūj, where he unfolds the Axumite-Ḥimyarite conflict.40

In 961 AD, Ḥamza al-Iṣfahānī (d. after 961) completed his chronology of pre-Islamic and Islamic dynasties, called Taʾrīkh sinī mulūk al-arḍ wa-l-anbiyāʾ.41 It consists of ten chapters, each giving a list of rulers of the different kingdoms and dynasties. In order, they are: the Persians, the Rūm (which comprises the Macedonians, the Romans, the Byzantines and the Ptolemids), the Greeks, the Copts, the Israelites,42 the Arabs of Iraq, the Arabs of Syria, the Arabs of Yemen, Kinda and lastly the Muslim Arabs. He was a native of Iṣfahān in Iran, and from the present work and another work of history of his native city,43 we can tell that he was somewhat of a Persian nationalist.44 In his eighth chapter on Ḥimyar and the Arabs of Yemen, he gives an account of the reign of Dhū Nuwās,45 which shows some peculiar differences from the other texts in this tradition, but it is closest perhaps to the text of Ibn Qutayba.46 The most striking difference is that Ḥamza gives a story about Dhū Nuwās’ conversion to Judaism and links him to the Jews of Yathrib:

Dhū Nuwās was the master of the Trench, and he was calling those in Yemen to become Jews (wa-l-dāʿī man bi-l-Yaman ilā al-tahawwud). Passing through it, he (once) stopped at Yathrib. Judaism appealed to him (fa-aʿjabathu al-yahūdiyya), so he became a Jew. The Jews of Yathrib incited him to attack Najrān in order to inflict trials on the Christians in it. They had adopted Christianity from a man who had come to them from the house of Jafna, the kings of Syria (mulūk al-Shām). So [Dhū Nuwās] set out towards them from [Yathrib]. He put them before trenches, which he had dug in the ground and kindled with fires, and then he submersed47 into them everyone who remained an adherent of Christianity. He brought this doing upon many of them, and he left [Najrān] and went to the royal residence in Yemen.48

Then follows the sequence of Dhū Thaʿlabān and the royal correspondence, which is in agreement with Ibn Hishām and Ibn Qutayba. Ḥamza’s biased knowledge of warfare (in the form of Persian equestrian warfare) is probably why the king of Abyssinia asks for the Emperor’s permission to dispatch horses to Yemen (an yujarrida khaylan ilā l-Yaman), instead of permission to set out towards Yemen (al-tawajjuh ilā l-Yaman), and why he has 70.000 riders (fāris) sent from Abyssinia instead of men, as in Ibn Hishām and Ibn Qutayba. Ḥamza gives the duration of Dhū Nuwās’ reign as twenty years, upon which the reign of Dhū Jadan follows. Here, the text is again very reminiscent of Ibn Qutayba’s text. There is no mention, however, of the woman and her son.

The last two sources in this textual tradition are a lot later. The Andalusian poet and historian, Ibn Saʿīd al-Maghribī (d. 1286), deals extensively with Yemeni folklore and traditions in his Nashwat al-ṭarab fī taʾrīkh jāhiliyyat al-ʿArab. Throughout this work, Ibn Saʿīd quotes explicitly from Kitāb al-tījān49 and from Ibn Qutayba, among others. The section on Dhū Nuwās50 is close to these two sources. From a text-critical point of view, the text is closest related to Ibn Qutayba’s text, but with many sporadic similarities to Ibn Hishām’s text. Ibn Saʿīd also has some unique textual features. It omits three sentences contained in the other sources (the mention of digging trenches and filling them with fire; the Emperor’s answer commanding the king of Abyssinia to give Dhū Thaʿlabān command over his people and to stay in Yemen; and finally Dhū Nuwās drowning).51 The elliptic list of Ḥimyarite kings in Abū l-Fidāʾ’s (d. 1331) Mukhtaṣar taʾrīkh al-bashar is derived from Ḥamza al-Iṣfahānī and Ibn Saʿīd al-Maghribī.52

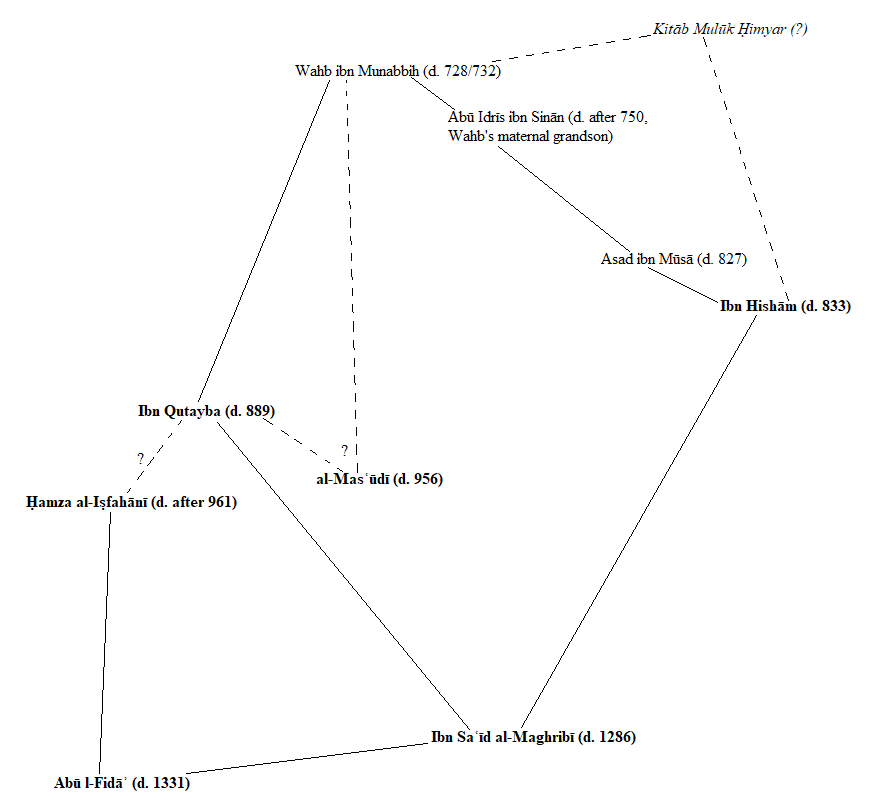

The exact relationships between the different texts in this tradition are hard to sort out, especially in what way al-Masʿūdī and Ḥamza relate to the tradition. Figure 1 is an attempt to present the tradition when both internal and external data are considered.53

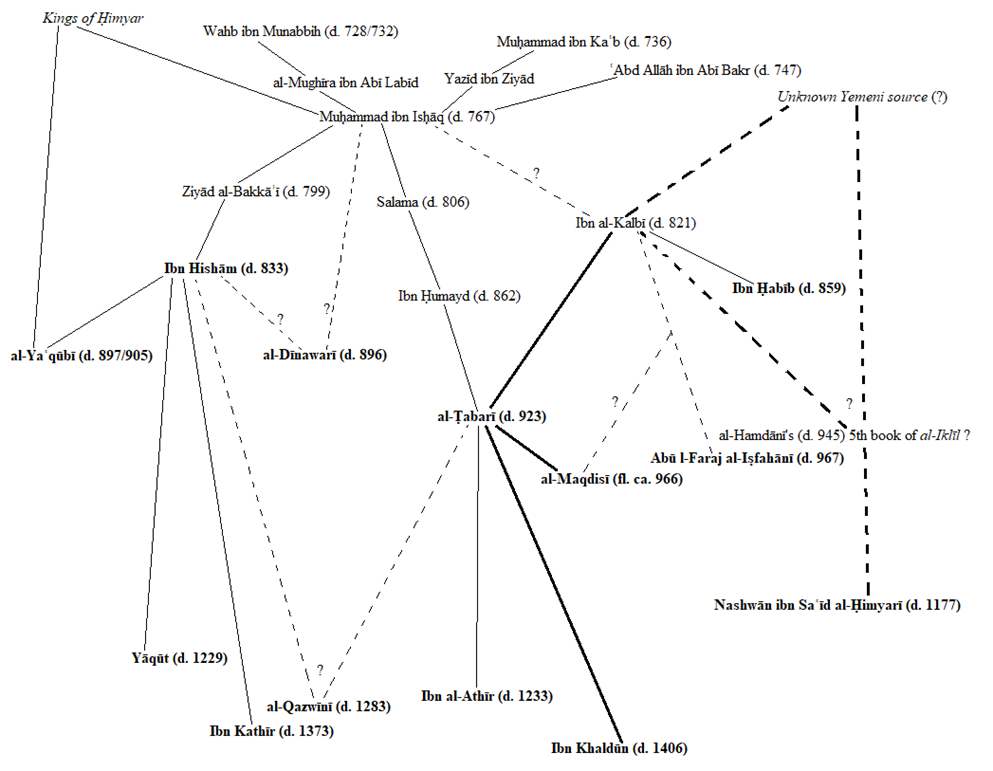

The Traditions from Ibn Isḥāq and Ibn al-Kalbī

Ibn Isḥāq

The second tradition about Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān is the most well known, both among Muslim historiographers and in Western scholarship. The Sīrat Rasūl Allāh by Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq (d. 767) is famous for being the earliest chronologically systematic presentation of the life of the prophet Muḥammad. Among other attestations, it is preserved in large portions through a redaction done by Ibn Hishām (d. 833) and through extensive quotations in the large Taʾrīkh by al-Ṭabarī (d. 923). In connection to the theme of Najrān, Western scholars have in particular been interested in the two different accounts of the Christianization of Najrān, and in the question of which Christian sources could have been the Vorlagen of the accounts.54 The first story of Christianization concerns the pious builder Faymiyūn and his disciple Ṣāliḥ, and their activities in Syria. It tells of Faymiyūn’s powers through prayers and oaths—he kills a seven-headed snake with a curse and heals several sick people through prayer. Faymiyūn and Ṣāliḥ are then captured by Arabs and taken to Najrān, where they are sold as slaves to different masters. The people of Najrān eventually adopt Faymiyūn’s religion after he destroys their object of worship, a tall palm-tree, with a prayer.

The second account deals with a native boy of Najrān called ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir, who, instead of attending classes with the local sorcerer, is instructed in the laws of Islam by an anonymous man who is harmonized by Ibn Isḥāq as Faymiyūn from the first account. After ʿAbd Allāh obtains knowledge of the Great Name of God through his own ingenuity, he initiates a career of converting and healing in Najrān, which attracts the attention of the displeased king, who attempts to execute him. The king only succeeds once he himself acknowledges the unity of God. The people of Najrān accept ʿAbd Allāh’s religion after the king miraculously drops dead after killing ʿAbd Allāh.

The two accounts are attributed to different sources. The Faymiyūn story is told on authority of Wahb ibn Munabbih,55 while the story of ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir is told on authority of Muḥammad ibn Kaʿb al-Quraẓī. While the religion of Faymiyūn is termed the “religion of ʿĪsā ibn Maryam,” the religion of ʿAbd Allāh is described wholly in anachronistic Islamic terms. Both accounts end with Ibn Isḥāq’s concluding statements that certain ‘innovations’ came upon the people of Najrān and their religion which were the origin of Christianity (al-naṣrāniyya) in Najrān. Ibn Isḥāq adds the story of Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān in a surprisingly brief form to the end of the ʿAbd Allāh story:

He (i.e., Ibn Isḥāq) related: Dhū Nuwās marched against them with his forces of the Ḥimyarites and the tribes of Yemen. He gathered the people of Najrān together, and summoned them to the Jewish faith, offering them the choice between that and being killed. They chose being killed, so he dug out for them the trench (al-ukhdūd). He burnt some of them with fire, slew some violently with the sword, and mutilated them savagely until he had killed nearly twenty thousand of them. (Translation by Bosworth (1999, 202))56

Then follows the sequence of Daws Dhū Thaʿlabān and the royal correspondence, which is different from the Kings of Ḥimyar narrative, as I mentioned in connection with al-Masʿūdī’s text. Dhū Thaʿlabān travels directly to the Byzantine Emperor, who issues an order to the Negus about intervention in Yemen, due to the shorter distance between Abyssinia and Yemen. The Negus sends out an army of 70.000 men. Dhū Nuwās tries to rally his forces among Ḥimyar and the tribes of Yemen, but is unsuccessful due to divisions within the Yemenite army. Dhū Nuwās is defeated and drowns himself in the sea.57

Apart from Ibn Hishām’s redaction of the Sīra, the earliest source, which derives its information from Ibn Isḥāq, is the universal history of Aḥmad al-Yaʿqūbī (d. 897/905). In his history, al-Yaʿqūbī paraphrases the general narrative including the story of ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir:

King Dhū Nuwās ibn Asʿad, whose name was Zurʿa, was unruly. He was the master of the Trench, which was (pertaining to the affair that) he was an adherent of the religion of Judaism, and a man called ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir, who was an adherent to the religion of Christ, had come to Yemen. He proclaimed his religion in Yemen. Whenever he saw a sick or ill person, he said: ‘Invoke God for your own sake that he may cure you and you may turn away from the religion of your people!’ and [the sick one] would do this, so his followers increased in number. [The news] reached Dhū Nuwās, so he began to search out everyone who professed this religion and to dig the trench in the ground for them. He was burning with fire and killing with the sword until he had annihilated them. So a man among them travelled to the Negus, who was an adherent of the religion of Christianity. The Negus dispatched to Yemen a man called Aryāṭ with troops against them. They were 70.000 (in number). Together with Aryāṭ was Abraha al-Ashram among his troops. Dhū Nuwās went out towards him. When they clashed together, Dhū Nuwās was defeated. When he saw the scattered state of his people and their defeat, he beat his horse and jumped with it into the sea. This was the last that was seen of him. The reign of Dhū Nuwās lasted for 68 years.58

Even though it is relatively clear that al-Yaʿqūbī drew on Ibn Isḥāq59 for this piece, the relationship is more complicated than it first seems. The overall narrative template into which the Ibn Isḥāq material is poured is from a source from the tradition of the Kings of Ḥimyar. The passage is included in a list of kings with the heading “Kings of Yemen,” the sequence of the royal correspondence agrees with Kitāb al-tījān and Ibn Qutayba, and the duration of Dhū Nuwās’ reign is given as 68 years in agreement with Ibn Qutayba. This harmonization of sources is probably also why ʿAbd Allāh is presented as a missionary who ‘had come to Yemen,’ as is the case with the missionary from the house of Jafna, instead of a native Najrānī boy, as in Ibn Isḥāq. The exact identity of this ‘Kings of Ḥimyar source,’ which has provided the skeleton for al-Yaʿqūbī, is uncertain.

Gradually, Muslim authors became less creative, but more rigid/faithful in transmitting the material from Ibn Isḥāq. Thus, Yāqūt (d. 1229) relates the accounts according to Ibn Hishām very faithfully,60 and later Ibn Kathīr (d. 1373) does the same.61 The version according to al-Ṭabarī is transmitted by Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1232),62 and later more loosely in Ibn Khaldūn (d. 1406).63 Al-Qazwīnī (d. 1283) transmits an abridged version of the story of ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir (corrupted to al-Nāmir), who is called “Master of the martyrs of Najrān” (sayyid shuhadāʾ Najrān).64

Ibn al-Kalbī

In juxtaposition to the material of Ibn Isḥāq, al-Ṭabarī transmits the story as it is witnessed by Hishām ibn Muḥammad al-Kalbī (d. 821), generally known as Ibn al-Kalbī.65 It contains some major deviances from Ibn Isḥāq. I quote here in full the relevant passages from Bosworth’s translation:

As for Hishām b. Muḥammad, he says that the royal power in Yemen was handed down continuously, with no one venturing to contest it until the Abyssinians (al-Ḥabashah) seized control of their land in the time of Anūsharwān. He related: The reason for their conquest was that Dhū Nuwās the Ḥimyarite exercised royal power in Yemen at that time, and he was an adherent of the Jewish faith. There came to him a Jew called Daws from the people of Najrān, who told him that the people of Najrān had unjustly slain his two sons; he now sought Dhū Nuwās’s help against them. The people of Najrān were Christians. Dhū Nuwās was a fervent partisan of the Jewish faith, so he led an expedition against the people of Najrān, killing large numbers of them. A man from the people of Najrān fled and in due course came to the King of Abyssinia. He informed the king of what the Yemenis had committed and gave him a copy of the Gospels partly burned by the fire. The King of Abyssinia said to him: “I have plenty of men, but no ships [to transport them], but I will write to Qayṣar (i.e., the Byzantine Emperor) asking him to send me ships for transporting the soldiers.” Hence he wrote to Qayṣar about this matter, enclosing the [partly] burned copy of the Gospels, and Qayṣar dispatched a large number of ships.

[…]

As for Hishām b. Muḥammad, he asserts that when the ships sent by Qayṣar reached the Najāshī, the latter transported his army by means of them, and the troops landed on the coast of al-Mandab. He related: When Dhū Nuwās heard of their approach, he wrote to the local princes (maqāwil) summoning them to provide him with military support and to unite in combating the invading army to repel it from their land. But they refused, saying, “Let each man fight for his own princedom (maqwalah) and region.” When Dhū Nuwās saw that, he had a large number of keys made, and then loaded them on to a troop of camels and set out until he came up with the [Abyssinian] host. He said: “These are the keys to the treasuries of Yemen, which I have brought to you. You can have the money and the land, but spare the menfolk and the women and children.” The army’s leader said, “I will write to the king,” so he wrote to the Najāshī. The latter wrote back to the leader ordering him to take possession from the Yemenis of the treasuries. Dhū Nuwās accompanied them until, when he brought them into Ṣanʿāʾ, he told the leader, “Dispatch trusted members of your troops to take possession of these treasuries.” The leader divided up his trusted followers into detachments to go and take possession of the treasuries, handing over the keys to them. [Meanwhile,] Dhū Nuwās’s letters had been sent to every region, containing the message “Slaughter every black bull within your land.” Hence they massacred the Abyssinians so that none were left alive except for those who managed to escape.

The Najāshī heard what Dhū Nuwās had done and sent against him seventy thousand men under the command of two leaders, one of them being Abrahah al-Ashram. When they reached Ṣanʿāʾ and Dhū Nuwās realized that he had not the strength to withstand them, he rode off on his horse, came to the edge of the sea amd [sic] rushed headlong into it; this was the last ever seen of Dhū Nuwās. (Translation by Bosworth (1999, 204–5, 211–12)).66

There are great differences between Ibn Isḥāq and Ibn al-Kalbī, which is also why al-Ṭabarī quotes from them both supplementing each other. The motive of Dhū Nuwās’ aggression against the people of Najrān is here one of revenge. The Christians of Najrān have killed two Jewish boys, and the zealous Dhū Nuwās avenges them by raiding (ghazā) the Christians and killing them in large numbers. The sequence of the royal correspondence is also in the reverse order as in the Kings of Ḥimyar tradition.

This version of the story is also found in the commentary to Nashwān ibn Saʿīd al-Ḥimyarī’s (d. 1177) poem on the kings of Ḥimyar. It sets the setting with the statement that a civil strife67 had broken out in Najrān between Jews and Christians: “A Jew of Najrān complained to him (Dhū Nuwās) about the superiority (ghalaba) of the Christians, as there was a civil strife (fitna) going on between the Jews and the Christians in Najrān. So Dhū Nuwās set out with the army towards Najrān.”68 Nashwān’s version follows the one in Ibn al-Kalbī closely, including the incident of the trick with the keys to the treasuries and the two different military expeditions from Abyssinia. The fact that Nashwān was a noble Yemenite living near Ṣanʿāʾ, giving him access to native sources, suggests that his account is transmitted not directly through Ibn al-Kalbī.69 This suggestion is also supported by numerous details in Nashwān’s text which are not found in Ibn al-Kalbī: The anonymous man who flees to Abyssinia in Ibn al-Kalbī is identified in Nashwān’s text as Dhu Thaʿlabān, where he does not flee, but is enraged because of what Dhū Nuwās had done to his fellow religionists, and therefore goes to Abyssinia to rally support.70 The army leader of the first expedition is named Kālib, or Barbakī, who is sent to Yemen by the Negus with an army of 30.000 men.71 On the other hand, Nashwān does not transmit certain passages extant in Ibn al-Kalbī, such as the involvement of the Emperor and the burned Gospel book.

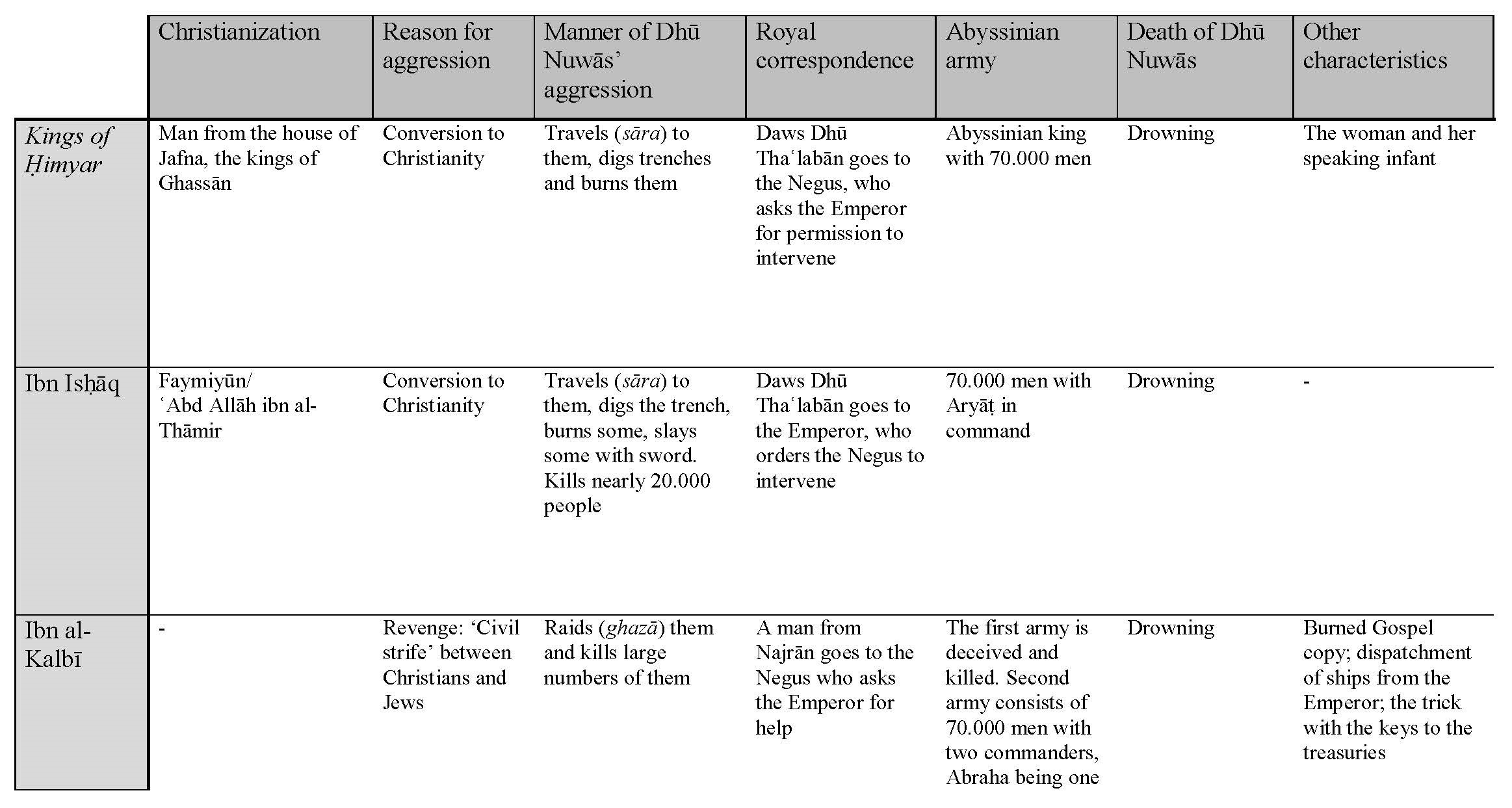

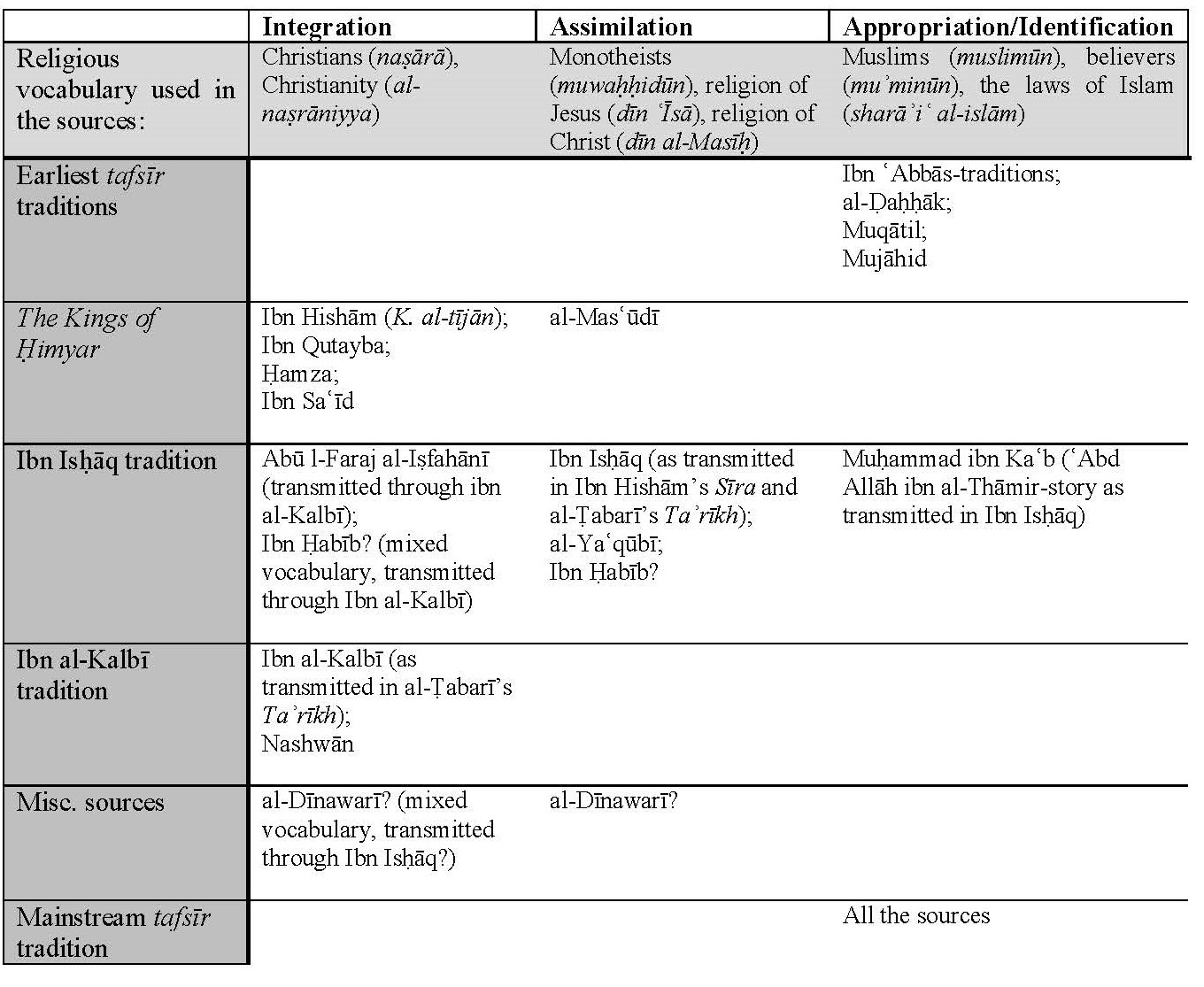

Textual and literary relationship can be established from external information, explicit references to sources and/or internal textual and narrative differences/similarities. When no explicit reference or external information exists, internal differences and similarities are the only way to associate a specific source with a larger textual tradition. So far, the narrative characteristics of the three different textual traditions can be described as follows in the table in figure 1, which can serve as a checklist for future sources.

Let us put the table in figure 1 to the test. Ibn Ḥabīb (d. 859) was a student of Ibn al-Kalbī,72 and in his Kitāb al-muḥabbar he included a section on the kings of Ḥimyar on the authority of Ibn al-Kalbī.73 The passage on Dhū Nuwās, however, also contains material found in Ibn Isḥāq:

So Zurʿa Dhū Nuwās jumped on him (i.e., Dhū Shanātir) and killed him. He became king after him. Then he became a Jew and he professed Judaism, and called the people to it. He was only pleased with people (who professed) Judaism, otherwise (they would suffer) execution. He was named Yūsuf and was the master of the Trench. He dug trenches in Najrān and lit them with fire. He called its people to Judaism. They were inheritors of a religion of the religion of ʿĪsā, God bless him. When they refused this, he threw them into the fire, burned the Gospel, and killed about 20.000 of them with the sword, apart from those he burned with fire, or savagely punished. Because of this, the Abyssinians came to Yemen, for it had reached them what he had done to the Christians. When Dhū Nuwās attacked the Abyssinians, his troops were scattered. He headed (iʿtaraḍa) to the sea on his horse and drowned (himself) out of fear of being captured. This was the last that was seen of him.74

Textually, a passage in Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī’s (d. 967) Kitāb al-aghānī75 shows signs of belonging to a similar stream of transmission as Ibn Ḥabīb.76 Al-Iṣfahānī tells us that Dhū Nuwās raided (ghazā) the people of Najrān and besieged them. He burned the people in trenches for not adopting Judaism, burned the Gospel and tore down the church (bīʿa) in Najrān. The sequence of Dhū Thaʿlabān and the royal correspondence is similar to Ibn Isḥāq’s version: Dhū Thaʿlabān shakes off his pursuers through the sandy desert and rides to the Emperor, who refers him to Abyssinia. Al-Iṣfahānī includes three speeches: one by Dhū Thaʿlabān (about the humiliation of the Arabs when they find themselves trampled underfoot by the black Abyssinians due to their different skin-color and traditions), one by the king of Abyssinia as he dispatches an army of 70.000 men and an elephant (commanding Aryāṭ to kill a third of the Yemenite men, etc., as in al-Ṭabarī’s version of Ibn Isḥāq), and one by Aryāṭ (delivering a speech77 of encouragement to his forces). At the end of the paragraph, al-Iṣfahānī gives an account of the suicide of Dhū Nuwās which resembles the account of Ibn Ḥabīb closely: “They (the Ḥimyarite army) were defeated in every respect. When Dhū Nuwās was taken by fear of being captured, (he made) his horse gallop, and (riding) on it the sea appeared (istaʿraḍa). He said (to himself): ‘Death in the sea is better than the captivity of the black!’”78

What do we make of this? Apart from the inclusion of the burned Gospel, the accounts of Ibn Ḥabīb and al-Iṣfahānī certainly bear more resemblance to Ibn Isḥāq’s version than to Ibn al-Kalbī’s, as it is contained in al-Ṭabarī. The fact that Ibn Ḥabīb explicitly draws his material from his teacher suggests that Ibn al-Kalbī transmitted more than one tradition about Dhū Nuwās and the Abyssinian conquest of Yemen79 in the course of his prolific career.80 It is quite likely that Ibn al-Kalbī transmitted traditions from Ibn Isḥāq in addition to the narrative later transmitted by al-Ṭabarī.

Figure 2 presents my view of the mutual relationships in the tradition family of Ibn Isḥāq/Ibn al-Kalbī.81

Miscellaneous Historiographical Sources

Apart of the sources, which can more or less easily be put into connection with one of the three textual strains of tradition, there are a couple of historiographical sources which are more difficult to associate with any one tradition.82

al-Dīnawarī

Of all the texts dealt with in the present article, the universal history Kitāb al-akhbār al-ṭiwāl by al-Dīnawarī (d. 896)83 is the source to which it is hardest to find an equivalent. Apart from having the same antagonists, it deviates on so many points from the other narratives:

They said: In the reign of Qubādh ibn Fīrūz, Rabīʿa ibn Naṣr the Lakhmite died, so sovereignty returned to Ḥimyar.84 Dhū Nuwās took rule over them, (he) whose name was Zurʿa ibn Zayd ibn Kaʿb Kahf al-Ẓulm ibn Zayd ibn Sahl ibn ʿAmrū ibn Qays ibn Jusham ibn Wāʾil ibn ʿAbd Shams ibn al-Ghawth ibn Jadār ibn Qaṭan ibn ʿArīb ibn al-Rāʾish ibn Ḥimyar ibn Sabaʾ ibn Yashjab ibn Yaʿrub ibn Qaḥṭān, but he was called Dhū Nuwās because of a lock of hair that was dangling (kānat tanūsu) from his head.

They said: In the land of Yemen, Dhū Nuwās had a fire, which he and his tribe were worshipping. From this fire, a portion (lit. “a neck”) was extending outwards, reaching a measure of three parasangs, and then returning to its place. Then some of the Jews in Yemen said to Dhū Nuwās: “O king, verily your worship of this fire is vain. If you professed our religion, we would extinguish it with the help of God so that you will learn that you are at risk because of your religion. He agreed with them to adopt their religion if they extinguished it. When this portion (of fire) went out, they brought out the Torah, opened it and began to recite it, and the fire diminished until it ended up in the house in which it was. They did not cease reading the Torah aloud until it was extinguished. So Dhū Nuwās became Jewish and called upon the people of Yemen to adopt (Judaism), and he killed whoever refused. Then he travelled to the city of Najrān to make those of the Christians in it Jews. In it, there was a tribe adhering to the religion of Christ (dīn al-Masīḥ), which had not been changed, and he called upon them to renounce their religion and adopt Judaism, but they refused. So he ordered that their king, whose name was ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir, be beheaded by sword. Then he was brought within the wall of the city, and seized upon it.85 He dug trenches for the ones remaining and burned them in them. They were the People of the Trench, of whom God tells (may his name be exalted) in the Qurʾān. Daws dhū Thaʿlabān escaped and travelled to the king the Byzantines and told him what Dhū Nuwās had done to the people of his religion: killing the bishops, burning the Gospel and razing the churches. So he wrote to the Negus, king of the Ethiopians, and he sent Aryāṭ with a great army. He travelled by sea until he got out on the shore of ʿAdan. Dhū Nuwās went towards him and fought him, and Dhū Nuwās was killed. So Aryāṭ entered Ṣanʿāʾ […]86

It has been suggested that this passage is, among others in al-Dīnawarī, reliant on Ibn Isḥāq.87 It does show features which are either similar to the account in Ibn Isḥāq, or have been adapted for other purposes: Al-Dīnawarī mentions the ‘Christianity’ in Najrān as an unchanged monotheistic religion, and Daws Dhū Thaʿlabān goes directly to the Emperor, not to the Negus. On these two points, the text fits the account of Ibn Isḥāq. However, al-Dīnawarī gives a different account on almost all other points of the narrative: Dhū Nuwās is appointed by the Persian king Qubādh (Kavad I); ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir is the king of Najrān and is beheaded by Dhū Nuwās; Al-Dīnawarī says that Dhū Nuwās killed bishops, burned the Gospel and tore down churches (which resembles the account in Kitāb al-aghānī); and Dhū Nuwās does not drown himself in the sea as all other accounts tell us, but is killed in battle against the Abyssinians.

Al-Dīnawarī clearly told his history from a Persian perspective, which is probably why Dhū Nuwās is put in close connection with the Sassanid Empire, and why he has Dhū Nuwās worship a giant fire in a temple (bayt). It is true that the conversion story has close affinities to an account in the Sīra, but there it is in connection with king Tubbaʿ Abū Karib Asʿad, where two rabbis convert the people of Yemen through an ordeal by fire.88 The decapitation of ʿAbd Allāh could maybe be reminiscent of Dhū Nuwās’ decapitation of Lakhnīʿa Dhū Shanātir,89 but again, the differences are major and too many to simply ascribe the passage in al-Dīnawarī to Ibn Isḥāq.

al-Hamdānī

We unfortunately only have the next source in fragments. Only four (nos. I, II, VIII and X) out of ten books of the Iklīl by the great South Arabian scholar, al-Hamdānī (d. 945),90 are extant. We can tell from the table of contents in book VIII that the fifth book dealt with Yemenite history from Asʿad Tubbaʿ up until the time of Dhū Nuwās,91 but we can only speculate about what tradition this volume contained and hope that it will be discovered in the future.92 There are, however, two passages in the eighth book which deal with the Dhū Nuwās episode. In a list of tombs of legendary persons, the story of the discovery of the tomb of ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir is found,93 which is quite similar but not identical with the one narrated by Ibn Isḥāq on the authority of ʿAbd Allāh ibn Abī Bakr.94 Enveloped in al-Hamdānī’s account, is a short narration of the events in Najrān: “this man was one of those who believed in the disciples of Jesus. His companions were burnt to death by the king of al-Yaman in ‘the fire of the ditch,’ referred to by God in His book where He says, […]. ʿAbdullāh ibn-al-Thāmir, however, was killed and buried without being mutilated [or burnt].”95 In the very last entry of the last section entitled “Memory of what has been preserved of the lamentations of Ḥimyar and the location of their graves”96, al-Hamdānī gives very sparse information about Dhū Nuwās,97 and the only thing that can be said of value is that the poetry given here corresponds to that found in the entry on Dhū Nuwās in Kitāb al-tījān.98

al-Maqdisī

The last source is not particularly difficult to place in terms of relationship, but it is difficult to place within one specific tradition. The Kitāb al-badʾ wa-l-taʾrīkh of al-Maqdisī (fl. ca. 966)99 contains the story of Faymiyūn (corrupted in al-Maqdisī as Faymūn) according to the report of Ibn Isḥāq on authority of Wahb.100 This account, however, contains sentences about the agreements between the Jews and Christians of Najrān not to betray each other, which is only found in the tafsīr of al-Ṭabarī, and the account of the woman and her boy is added to the end of the story.101 The detail that Dhū Nuwās besieged (ḥāṣara/ḥaṣara) Najrān is also found in Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī. After the Ibn Isḥāq account, al-Maqdisī goes on to give another account of the same narrative, namely the Ibn al-Kalbī account also given by al-Ṭabarī in his history: “Apart from this (account), there has been told (another account) concerning the story of the Trench, and we have mentioned it in the Book of Good Qualities (Kitāb al-maʿānī).”102 The most obvious hypothesis of relationship is that al-Maqdisī derives his material from al-Ṭabarī, both from the Tafsīr and the history with possible influences from a tradition which ultimately informed al-Iṣfahānī.

The Mainstream tafsīr Tradition

After the first generations of mufassirūn, a particular story seems to have won a place of pride in the collective memory concerning the aṣḥāb al-ukhdūd (Q85:4) among authors writing exegetical works and works of ḥadīth. An adaptation of the ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Thāmir story is found in most works of tafsīr from the beginning of the ninth century onwards, and in a couple of ḥadīth compilations. Two different recensions exist, the first of which exists in many ‘subrecensions.’

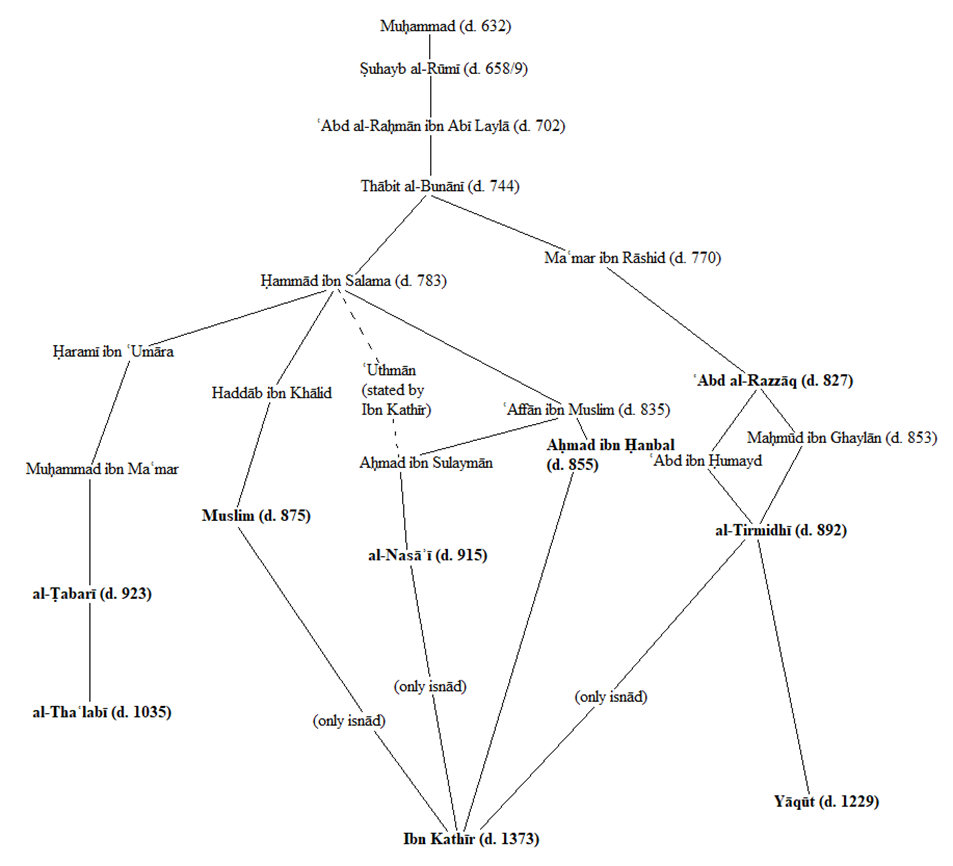

The Ṣuhayb Recension

Disregarding the many small differences between the subrecensions, the overall narrative runs as follows: The royal sorcerer (or soothsayer) appeals to the king with a request to get an apprentice to whom he can pass on his knowledge and tradition. The apprentice boy has to commute past a monk’s cell on his way to the sorcerer, and he is gradually converted to Islam by asking questions to the monk. The boy miraculously kills a creature which blocks the road and heals a blind man. After the king has killed the monk and the (formerly) blind man after having extracted intelligence about the boy, he tries to kill the boy as well. After two failed attempts (throwing him off a mountain and drowning him at sea), he finally succeeds with the help of the boy’s own instructions: He has to crucify him and shoot him with arrows while acknowledging God. The people subsequently adopt the religion of the boy, so the king digs trenches and burns them. In some accounts, the story of the woman and her son is added.103

Compared to the story in Ibn Isḥāq, this ‘tafsīr version’ has been stripped of all contextual information. The name of neither the boy nor the king is given (no name occurs in the texts at all), there is no temporal indication and often even the location of Najrān is left out. This is probably deliberate, because it makes the story more flexible and lends itself more smoothly to interpretation. The primary sources for this recension are ʿAbd al-Razzāq (d. 827),104 Ibn Ḥanbal (d. 855),105 al-Nasāʾī (d. 915),106 Muslim (d. 875)107 and al-Ṭabarī (d. 923).108 Each of these sources give slightly different versions through slightly different chains of transmission. They all ultimately transmit the story on authority of Ṣuhayb al-Rūmī (d. 658/9), who received it from Muḥammad himself. Ibn Kathīr109 transmits the story through Ibn Ḥanbal, but tells us that al-Tirmidhī, al-Nasāʾī and Muslim also transmit the story. ʿAbd al-Razzāq, however, breaks off one chain earlier (at Thābit al-Bunānī (d. 744)), before the other sources diverge on different paths of transmission (from Ḥammād ibn Salama (d. 783)). This should also be manifest in the wording of the text, and this is indeed the case. Where all the other sources have one of the antagonists as sorcerer (sāḥir), ʿAbd al-Razzāq has a soothsayer (kāhin), and where the story of the woman and her son is extant in all the other sources, it is absent in ʿAbd al-Razzāq. This is confirmed by those later authors who transmit from ʿAbd al-Razzāq.110 Whereas David Cook views the story of the woman and her son as an added element,111 he does not draw the consequences of his study. It is reasonable to suggest that the story was added by Ḥammād ibn Salama, or at some point between him and Thābit, i.e., before 783 AD. The relationship between the Ibn Isḥāq story and the version found in these tafsīr and ḥadīth works is difficult to figure out. If we are to believe the isnāds in their entirety, then the latter version is not dependent on Ibn Isḥāq, and the story has entered the Islamic tradition twice through two different sources, one Jewish-Yemenite (Muḥammad ibn Kaʿb) and one Christian-Syrian/Iraqi (Ṣuhayb al-Rūmī).112 However, it is possible that the first part of the isnād, Muḥammad → Ṣuhayb → Ibn Abī Laylā, is fabricated, and that the story is, in fact, the one related from Muḥammad ibn Kaʿb (and preserved in the Sīra), which subsequently was adapted for the purposes of tafsīr and ḥadīth.113 For a visualization of the reported chains of transmission, see figure 1.

The Ibn ʿAbbās Recension

The Ṣuhayb recension was in time reworked and clothed again in the explicit context of Najrān and the Martyrs. In Qiṣaṣ al-ʾanbiyāʾ, al-Thaʿlabī (d. 1035)114 transmits a story related by ʿAṭāʾ on authority of Ibn ʿAbbās, where the king is called Yūsuf Dhū Nuwās ibn Shuraḥbīl, and the boy ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Sāmir (sic). The narrative has been smoothed out and certain vague points have been made more concrete (the creature blocking the road is, for example, a snake, the blind man is the king’s nephew). The woman does not have one, but three children, who are all in turn thrown into the fire. This recension was clearly meant for entertainment purposes, smoothing out points of inconsistency in the narrative, and the contextualization makes it easier to visualize and imagine the story. Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1233) also transmits this version of the story on authority of Ibn ʿAbbās.115

Conclusions

Through this survey of a wide variety of sources, the Islamic tradition of Dhū Nuwās and the Martyrs of Najrān appears a lot more diverse than what is usually the impression one gets from reading the paraphrases of scholars working within the history of late Antiquity and Religious Studies. Three main traditions within the historiographical genre have emerged, each with its own group of transmitters. The tradition of the anonymous work of The Kings of Ḥimyar is probably the oldest tradition, going back to Wahb ibn Munabbih, if not further. In the middle of the eighth century, Ibn Isḥāq likely used this work to structure the pre-Islamic section (mubtadiʾ) of his biography of the Prophet. In this text, the Martyrs of Najrān are said to adhere to ‘the religion of Jesus,’ a pure monotheistic kind of Christianity, the followers of which Muḥammad would later encounter in Medina, albeit by then adherents of a corrupted Christianity (al-naṣrāniyya). Another tradition transmitted primarily by Ibn al-Kalbī exhibits many differences from this key text, among them a difference in motive. In Ibn al-Kalbī, Dhū Nuwās seems to be motivated by revenge during a civil strife between Christians and Jews. Being a Jew himself, he of course sides with the Jewish party, and thus invites the Axumite kingdom to the escalating conflict. However, in the genres with direct legal implications, i.e., tafsīr and ḥadīth, the Martyrs of Najrān are often appropriated as ‘proto-Muslims.’ Both in the very early stages of Qurʾānic exegesis, and in the later story of the boy and the monk, the religious nomenclature is entirely Islamic in character. Occasionally, they are identified as ‘the Christians of Yemen,’ but always in juxtaposition with terms such as ‘believers,’ ‘monotheists,’ or ‘Muslims.’ It is hard to systematize exactly how the different Muslim writers have dealt with and incorporated the Martyrs of Najrān into their respective historiographical, exegetical and legal narratives. Nevertheless, in the following table in figure 1 I have, in order to give some overview, made a crude distinction between 1) integrating the Christian Martyrs of Najrān as Christians, adherents of Christianity, i.e., the religion, which the writers themselves would have been familiar with through interaction with their contemporaries, 2) assimilating the Martyrs to the prophetic/revelatory narrative of Islam, being adherents of the ‘unspoiled’ monotheistic religion of God’s prophet, Jesus, which later was corrupted into the schismatic religion, Christianity, and 3) appropriating the Martyrs as Muslims proper using only Islamic lingo as ‘believers,’ ‘Muslims,’ followers of the laws of Islam, etc., by which the writer establishes a religious identification between the Martyrs and himself and his recipients.

Interest in the religion of the perpetrator, Dhū Nuwās, falls along the same lines as that of the Martyrs. Whereas the ‘appropriating/identifying’ sources of tafsīr and ḥadīth are not interested in the specific religion of the anonymous king—only that he tries to force the believers to apostatize from ‘Islam’—many of the ‘integrating’ and ‘assimilating’ sources of historiographical character are interested in the Jewish religion of Dhū Nuwās. Two writers, al-Dīnawarī and Ḥamza, even add stories about his conversion to Judaism to their narratives. Thus, the sources also take different approaches to the interreligious elements of the narrative. Some authors, such as the two just mentioned, and for example Ibn al-Kalbī, are interested in the specific religious factions, and highlight this dimension of the narrative accordingly by explicating the exact reason for Dhū Nuwās’ aggression. Others are primarily interested in the Martyrs as pure monotheists and pre-Islamic adherents of the true religion, and in these cases the religion of Dhū Nuwās is downplayed—he is most often explicitly Jewish, but it is mentioned in passing—such as in al-Masʿūdī and Ibn Isḥāq. The tafsīr sources are not interested in these matters, as they have alleviated the original religious categories for the purposes of Islamic edification.

The reconstruction, sometimes by conjecture, of the relationships between the different sources which I have put forth in the present contribution is by no means bulletproof, but I hope at least to have fertilized the ground for further study of the Islamic literary works which deal with this intriguing set of events in history, not just as containers for earlier Christian material, but as interesting religious expressions with their own set of agendas.

Primary Sources

- ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿānī

Kitāb al-muṣannaf: ed. Ḥabīb al-Raḥmān al-Aʿẓamī, al-Muṣannaf, 11 vols. + index, Beirut, 1970–83 [V, 420–423]

- Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī

Kitāb al-aghānī: ed. [various editors], Kitāb al-aghānī, 24 vols., Dar al-kutub, Egypt, 1928–94 [XVII, 303–304]

- Abū l-Fidāʾ

Mukhtaṣar taʾrīkh al-bashar: ed. and transl. Heinrich Fleischer, Abulfedae historia anteislamica, Leipzig, 1831 [118]

- Al-Bayḍāwī

Anwār al-tanzīl wa-asrār al-taʾwīl: ed. Heinrich Fleischer, Beidhawii commentarius in coranum, 2 vols., 1846–8 (reprint Osnabrück 1968) [II, 395]

- Al-Ḍaḥḥāk ibn Muzāḥim

Tafsīr: ed. Muḥammad Shukrī Aḥmad al-Zāwiyyatī, Tafsīr al-Ḍaḥḥāk, 2 vols., Cairo, 1999 [II, 950]

- Al-Dīnawarī

Kitāb al-akhbār al-ṭiwāl: ed. Vladimir Guirgass, Kitāb al-akhbār al-ṭiwāl, Leiden, 1888 [62–63]

- Al-Hamdānī

al-Iklīl al-juzʾ al-thāmin: ed. Nabīh Amīn Fāris, al-Iklīl al-juzʾ al-thāmin, Beirut & Ṣanʿāʾ, 1940 [2+134–135+226–227]

- Ḥamza al-Iṣfahānī

Taʾrīkh: ed. & transl. I. M. E. Gottwaldt, Hamzae Ispahanensis annalium libri X, 2 vols., St. Petersburg & Leipzig, 1844 [I, 133–134]; ed. [anon.], Taʾrīkh sinī mulūk wa-l-arḍ wa-l- ʾanbiyāʾ, Beirut, (1961) [105–106]

- Ibn al-Athīr

Al-Kāmil fī l-taʾrīkh: ed. Carolus Johannes Tornberg, Ibn-el-Athiri chronicon quod perfectissimum inscribitur, 12 vols., Leiden, 1853–67 [edition typeset anew in Beirut 1965–6 as Ibn al-Athīr al-Kāmil fi’l-taʾrīkh] [Beirut edition: I, 425–432]

- Ibn Ḥabīb

Kitāb al-muḥabbar: ed. Ilse Lichtenstädter, Kitāb al-muḥabbar, Hyderabad, 1942 [368]

- Ibn Ḥanbal

Musnad: ed. Shuʿayb al-Arnaʾūṭ (chief editor), Musnad al-Imām Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, 50 vols., Muʾassasa al-Risāla, Beirut, 1995–2001 [XXXIX, 351–354]

- Ibn Hishām

Sīra: ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, Das Leben Muhammed’s nach Muhammed Ibn Ishâk, 2 vols., Göttingen, 1858 [I, 20–26]

- Ibn Hishām

Kitāb al-tījān: ed. [anon.], Kitāb al-tījān fī mulūk Ḥimyar, Hyderabad, 1928 [301–302]

- Ibn Kathīr

Al-bidāya wa-l-nihāya: ed. ʿAbd Allāh al-Turkī, Al-bidāya wa-l-nihāya, 20 vols., Giza, 1997–9 [III, 133–136]

- Ibn Kathīr

Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-ʿaẓīm: ed. [anon.], Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-ʿaẓīm, 7 vols., Dar al-Fikr, Beirut, 1966 (3rd edition, 1970) [VII, 255–261]

- Ibn Khaldūn

Taʾrīkh: ed. Suhayl Zakkār, Muqaddima + Taʾrīkh ibn Khaldūn, 7 vols., Dar al-Fikr, Beirut, 2000–1 [II, 68–69]

- Ibn al-Mujāwir

Tārīkh al-mustabṣir: ed. Oscar Löfgren, Descriptio arabiae meridionalis, 2 vols., Brill, Leiden, 1951–4 [I, 95–96+II, 209]

- Ibn al-Nadīm

Fihrist: ed. Ayman Fu’ād Sayyid, Kitāb al-fihrist, 2 vols., al-Furqān, London, 2nd edition, 2014.

- Ibn Qutayba

Kitāb al-maʿārif: ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, Ibn Coteiba’s Handbuch der Geschichte, Göttingen, 1850 [311–312]

- Ibn Saʿīd al-Maghribī

Nashwat al-ṭarab fī taʾrīkh jāhiliyyat al-ʿarab: ed. Naṣrat ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, Nashwat al-ṭarab fī taʾrīkh jāhiliyyat al-ʿarab, 2 vols., Amman, 1982 [I, 156]

- Ibn Wahab al-Dīnawarī

Tafsīr: ed. Aḥmad Farīd, Tafsīr ibn Wahab, 2 vols., Beirut, 2003 [II, 487–488]

- Al-Maqdisī

Kitāb al-badʾ wa-l-taʾrīkh: ed. Clément Huart, Le livre de la création et de l’histoire, 6 vols., Paris, 1899–1919 [III, 182–185]

- Al-Masʿūdī

Murūj al-dhahab: ed. & revised, C. Barbier de Meynard & P. de Courteille & Charles Pellat, Maʿūdī: Les prairies d’or, 7 vols., Beyrouth, 1966–1979 [I, 74–75+II, 199–200]

- Mujāhid ibn Jabr

Tafsīr: ed. Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Salām Abū l-Nīl, Tafsīr al-Imām Mujāhid ibn Jabr, Giza, 1989 [718]

- Muqātil ibn Sulaymān

Tafsīr: ed. ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad, Tafsīr Muqātil ibn Sulaymān, 4 vols., Beirut, 2002 [IV, 647–648]

- Muslim

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim: ed. Hāfiz Abū Tāhir Zubayr ʿAli Zaʾi, tr. Nasiruddin al-Khattab, English Translation of Sahîh Muslim, 7 vols., Dar as-Salam, Riyadh, 2007 [VII, 401–405]

- Al-Nasāʾī

Tafsīr: ed. [anon.], Tafsīr al-Nasāʾī, 2 vols., Beirut, 1990 [II, 509–513]

- Nashwān ibn Saʿīd al-Ḥimyarī

Shams al-ʿulūm: ed. ʿAẓīmuddīn Aḥmad, Die auf Südarabien bezüglichen Angaben Našwān’s im Šams al-ʿulūm, Leiden & London, 1916 [15+31+106–107+116]

- Nashwān ibn Saʿīd al-Ḥimyarī

Mulūk Ḥimyar wa-ʾaqyāl al-Yaman: ed. ʿAlī ibn Ishmāʿīl al-Muʾtīd & Ishmāʿīl ibn Aḥmad al-Jarāfī, Mulūk Ḥimyar wa-ʾaqyāl al-Yaman, Beirut, 1978 [147–149]

- Al-Qazwīnī

Kitāb āthār al-bilād: ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, el-Cazwini’s Kosmographie, 2 vols., Göttingen, 1848–9 [II, 84]

- Al-Ṭabarī

Taʾrīkh: ed. M. J. de Goeje et al., Annales quos scripsit Abu Djafar Mohammed ibn Djarir at- Tabari, 15 vols., Leiden, 1879–1901 (reprint 1964) [II, 919–930]

- Al-Ṭabarī

Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl al-Qurʾān: ed. [anon.], Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl al-Qurʾān, 30 vols., Mostafa Bab Halabi & Sons Press, 1968 [XXX, 132–134]

- Al-Thaʿlabī

Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ: ed. [anon.], Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, Mostafa Bab Halabi & Sons Press, 1954 [436–439]

- Al-Thaʿlabī

Al-Kashf wa-l-bayān: ed. al-Imam Abī Muḥammad ibn ʿĀshwar, al-Kashf wa-l-bayān, 10 vols., Beirut, 2002 [X, 168–169]

- Al-Tirmidhī

al-Jāmiʿ al-kabīr: ed. [anon.], Sunan al-Tirmidhī wa-huwa al-Jāmiʿ al-kabīr, 4 vols. + index, Dār al-Taʾṣīl, Cairo, 2nd edition, 2016 [IV, 296–298]

- Al-Yaʿqūbī

Taʾrīkh: ed. M. Th. Houtsma, Ibn-Wādhih qui dicitur al-Jaʿqubī historiae, 2 vols., Leiden, 1883 (reprint 1969) [I, 225–226]

- Yāqūt

Kitāb muʿjam al-buldān: ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld, Jacut’s geographisches Wörterbuch, 6 vols., Leipzig, 1866–73 [IV, 752–757]

- Al-Zamakhsharī

Tafsīr al-kashshāf: ed. William Nassau Lees, The Kashshaf ’an Haqaiq al-tanzil, 2 vols., Calcutta, 1856 [II, 1594–1595]

Encyclopaedia of Islam Entries

EI2: Encyclopaedia of Islam, second edition

“al-Hamdānī”, by Oscar Löfgren.

“Ḥamza al-Iṣfahānī”, by Franz Rosenthal.

“Ibn Sharya”, by Franz Rosenthal.

“al-Masʿūdī”, by Charles Pellat.

“al-Muṭahhar b. Ṭāhir al-Maḳdisī”, by the editors (Ed.).

References

Adang, Camilla. 2006. “The Chronology of the Israelites According to Ḥamza Al-Iṣfahānī.” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 32: 286–310.

Arneson, Hans, Emanuel Fiano, Christine Luckritz Marquis, and Kyle Smith. 2010. The History of the Great Deeds of Bishop Paul of Qenṭos and Priest John of Edessa. Piscataway: Gorgias Press.

Bausi, Alessandro. 2017. “Il Gadla ʾAzqir.” Adamantius 23.

Bausi, Alessandro, and Alessandro Gori. 2006. Tradizioni orientali del “Martirio di Areta”. Florence: Dipartimento di Linguistica.

Beeston, A. F. L. 1985. “Two Bi’r Ḥimā Inscriptions Re-Examined.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 48 (1): 42–52.

———. 1989. “The Chain of Al-Mandab.” In On Both Sides of Al-Mandab, edited by Ulla Ehrensvärd and Christopher Toll. Stockholm: Svenska Forskninginstitutet i Istanbul.

Berg, Herbert. 2011. “The Isnād and the Production of Cultural Memory: Ibn ʿAbbās as a Case Study.” Numen 58: 259–83.

Binggeli, André. 2007. “Les versions orientales du Martyre de Saint Aréthas et de ses compagnons.” In Le Martyre de Saint Aréthas et de ses compagnons, edited by Marina Detoraki, 163–77. BHG 166. Paris: ssociation des amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance.

Bonner, Michael Richard Jackson. 2014. “An Historiographical Study of Abū Ḥanīfa Aḥmad ibn Dāwūd ibn Wanand al-Dīnawarī’s Kitāb al-Aḫbār al-Ṭiwāl.” PhD diss., Oxford: University of Oxford.

———. 2015. Al-Dīnawarī’s Kitāb al-aḫbār al-ṭiwāl: An Historiographical Study of Sasanian Iran. Leuven: Groupe pour l’Étude de la Civilisation du Moyen-Orient.

Bosworth, C. E. 1999. The History of Al-Ṭabarī. Volume V – the Sāsānids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen. New York: SUNY Press.

Bowersock, Glen W. 2013. The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brinner, William M. 2002. ʿArāʾis al-majālis fī qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, or: Lives of the Prophets. Leiden: Brill.

Cook, David. 2008. “The Aṣḥāb al-Ukhdūd: History and Ḥadīth in a Martyrological Sequence.” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 34: 125–48.

Crosby, Elise W. 2007. The History, Poetry, and Genealogy of the Yemen. The Akhbar of Abid B. Sharya Al-Jurhumi. Piscataway: Gorgias Press.

Detoraki, Marina. 2007. Le martyre de saint Aréthas et de ses compagnons. BHG 166. Paris: Association des amis du Centre d’histoire et civilisation de Byzance.

Donner, Fred McGraw. 1998. Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginning of Islamic Historical Writing. Princeton: The Darwin Press.

Faris, Nabih Amin. 1938. The Antiquities of South Arabia Being a Translation from the Arabic with Linguistic, Geographic, and Historic Notes of the Eighth Book of Al-Hamdāni’s Al-Iklīl. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fell, Winand. 1881. “Die Christenverfolgung in Südarabien und die ḥimjaritisch-äthiopischen Kriege nach abessinischer Überlieferung.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 35: 1–74.

Fleischhammer, Manfred. 2004. Die Quellen des Kitāb al-Aġānī. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Goldfeld, Isaiah. 1981. “The Tafsīr of Abdallah B. ʿAbbās.” Der Islam 58: 125–35.

Guidi, Ignazio. 1881. “La lettera di Simeone vescovo di Bêth-Arśâm sopra i martiri omeriti.” Atti della R. Accademia dei Lincei III (7): 471–515.

Guillaume, Alfred. 1955. The Life of Muhammad. A Translation of Isḥāq’s Sīrat Rasūl Allāh. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heer, F. Justus. 1898. Die historischen und geographischen Quellen in Jāqūt’s Geographischem Wörterbuch. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner.

Hirschberg, J. W. 1939–1949. “Nestorian Sources of North-Arabian Traditions on the Establishment and Persecution of Christianity in Yemen.” Rocznik Orientalistyczny 15: 321–38.

Jeffery, Arthur. 1946. “Christianity in South Arabia.” The Moslem World 36: 193–216.

Khalidi, Tarif. 1975. Islamic Historiography: The Histories of Mas’udi. New York: State University of New York Press.

———. 1976. “Muʿtazilite Historiography: Maqdisī’s Kitāb Al-Badʾ Waʾl-Taʾrīkh.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 35 (1): 1–12.

Khoury, Raif Georges. 1972. Wahb b. Munabbih. Teil 1. Der Heidelberger Papyrus PSR Heid Arab 23. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Kilpatrick, Hilary. 2003. Making the Great Book of Songs: Compilation and the Author’s Craft in Abû L-Faraj Al-Işbahânî’s Kitâb Al-Aghânî. London & New York: Routledge.

Koç, Mehmet Akif. 2008. “A Comparasion of the References to Muqātil B. Sulaymān (150/767) in the Exegesis of Al-Thaʿlabī (427/1036) with Muqātil’s Own Exegesis.” Journal of Semitic Studies 53 (1): 69–101.

Kremer, Alfred von. 1866. Über die südarabische Sage. Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus.

Lane, Edward William. 1863. An Arabic–English Lexicon. Vol. 8. London: Williams and Norgate.

La Spisa, Paolo. 2010. “Les versions arabes du Martyre de Saint Aréthas.” In Juifs et chrétiens en arabie aux Ve et VIe siècles: regards croisés sur les sources, edited by Joëlle Beaucamp, Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet, and Christian Julien Robin, 227–38. Paris: Association des amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance.

———. 2017. “Martirio e rappresaglia nell’Arabia meridionale dei secoli V e VI: uno sguardo sinottico tra fonti islamiche e cristiane.” Adamantius 23: 318–40.

Lecomte, Gérard. 1965. Ibn Qutayba (mort en 276/889): L’homme, son oeuvre, ses idées. Damascus: Institut Français de Damas.

Lichtenstädter, Ilse. 1939. “Muḥammad Ibn Ḥabîb and His Kitâb Al-Muḥabbar”.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society I (January): 1–27.

Mazuz, Haggai. 2016. “Possible Midrashic Sources in Muqātil B. Sulaymān’s Tafsīr.” Journal of Semitic Studies 61 (2): 497–505.

Moberg, Axel. 1924. The Book of the Himyarites: Fragments of a Hitherto Unknown Syriac Work. Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup.

———. 1925. “Kristna legender i Tabaris berättelser om kristendomen i Nagran.” In Studier tilegnede professor, dr. phil. & theol. Frants Buhl, edited by Johannes Jacobsen, phil., Frants Buhl, and Johannes Jacobsen, 137–50 , Copenhagen: V. Pios Boghandel.

———. 1930. Über einige christliche Legenden in der islamischen Tradition. Lund: Håkan Ohlssons Buchdruckeri.

Munt, Harry, Touraj Daryaee, Omar Edaibat, Robert Hoyland, and Isabel Toral-Niehoff. 2015. “Arabic and Persian Sources for Pre-Islamic Arabia.” In Arabs and Empires Before Islam, edited by Greg Fischer, 434–500. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Musurillo, Herbert. 1972. Acts of the Christian Martyrs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nickel, Gordon. 2006. “‘We Will Make Peace with You’: The Christians of Najrān in Muqātil’s Tafsīr.” Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 3: 171–88.

Power, Timothy. 2012. The Red Sea from Byzantium to the Caliphate AD 500–1000. Cairo & New York: The American University in Cairo Press.

Pregill, Michael. 2008. “Isrāʾīliyyāt, Myth, and Pseudepigraphy: Wahb B. Munabbih and the Early Islamic Versions of the Fall of Adam and Eve.” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 34: 215–84.

Prémare, Alfred-Louis de. 2005. “Wahb B. Munabbih, une figure singulière du premier islam.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 60 (3): 531–49.

Retsö, Jan. 2005–2006. “Wahb B. Munabbih, the Kitāb Al-Tījān and the History of Yemen.” Arabia 3: 227–36.

Rippin, Andrew. 1994. “Tafsīr Ibn ʿAbbās and Criteria for Dating Early Tafīr Texts.” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 18: 38–83.

Robin, Christian Julien. 2004. “Himyar et Israël.” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 148 (2): 831–908.

———. 2008. “Joseph, dernier roi de Ḥimyar (de 522 à 525, ou une de années suivantes).” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 34: 1–124.

———. 2010. “Nagrān vers l’époque du massacre: Notes sur l’histoire politique, économique et institutionelle et sur l’introduction du christianisme (avec un réexamen du Martyre d’Azqīr).” In Juifs et chrétiens en arabie aux ve et vie siècles: regards croisés sur les sources, edited by Joëlle Beaucamp, Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet, and Christian Julien Robin, 39–106. Paris: Association des amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance.

———. 2012. “Arabia and Ethiopia.” In The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, edited by Scott Fitzgerald Johnson, 247–332. Oxford: Oxford University Press.