From the Arab Lands to the Malabar Coast

The Arabic mawlid as a Literary Genre and a Traveling Text

This article explores the potential of literary-liturgical texts in tracing developments in intra-religious contacts. It deals with mawlid, which is both a literary genre and a devotional practice. By the thirteenth century, mawlid was established in various parts of the Muslim world as an annual feast and a public practice to commemorate the birthday of the prophet Muḥammad. One element of such festivities was the liturgical reading of a literary composition centring on the prophet’s birth and early life, in most cases simply termed mawlid. The article focusses on the intra-religious transcultural transfer of mawlid writing, namely from the Arab world to Muslim communities on the Malabar Coast, the western coast of South India. In analysing such a transfer, I identify texts and people that travelled between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean and examine the literary practices. The findings indicate that there is plausibility for dating the first Arabic mawlid compositions from Malabar to the early sixteenth century. I show how a mawlid text supposedly composed in thirteenth-century Andalusia and circulating as far as Yemen served as a genre model for the presumed first Arabic mawlid composition in Malabar. Furthermore, the social context of the Malabar composition draws on a transformation in the function of mawlid readings, which were, in the late fifteenth century, no longer limited to commemorating the birth anniversary. Finally, the mawlid’s aesthetic features and performance practices allowed a new experience of Arabic and reflect the rise of Muslim educational institutions and a growing Muslim population in the coastal towns of Malabar.

mawlid, mawlūd, Muslim ritual, Sharaf al-anām (Sharrafa l-anām), Manqūṣ (Manqoos) Mawlid, Malabar, Arabic Cosmopolis

Introduction

The phenomenon of Arabic Muslim texts that, due to their immense popularity, travelled between the Arab world and South Asian Muslims is well known. In this article, I am going to focus on mawlid texts, keeping in mind that mawlid is both a literary genre and a religious practice to commemorate the birth of the prophet Muḥammad. Mawlid texts became widespread from the late twelfth century onwards in different Arab regions and subsequently moved across languages, regions, and cultures (Abū l-Fatḥ 1995; Kaptein 1993; Katz 2007; Knappert 1988; Muneer 2015; Salakidis 2018). The present study explores the context of the presumed earliest Arabic mawlid text from Malabar and thereby an example of synchronic intra-religious contact. Taking mawlid as both a literary and liturgical genre, I examine an intra-religious ritual transfer into a new setting, namely the transfer of mawlid writing and performance as it was practiced in different parts of the Arab world, encompassing Andalusia, North Africa, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and the Arab Peninsula, to the Malabar Coast in South India, where the presumed earliest Arabic mawlid text was composed in the early sixteenth century.

Research on the Arabic mawlid so far has explored mainly the political and social context of mawlid celebrations, and much less attention was paid to the aesthetic forms connected to these celebrations. Even less is known on mawlid compositions from South Asia. Annemarie Schimmel, one of the few scholars in Islamic Studies to include South Asian literatures, seems to have been unaware of the Arabic mawlid texts written in India, since she describes mawlid literature in India as a late and primarily Persian-speaking development.1 Yet in my research on Arabic mawlid texts, I documented at least fifteen Arabic texts from South India. This paper seeks to explore the possible routes and channels of mawlid transfer and situate the presumed earliest mawlid text from South India into the wider tradition of Arabic mawlid compositions. Judging by the current state of research, hardly anything is known about mawlid practices in Malabar before the sixteenth century. The Arab traveller Ibn Baṭṭūṭa (d. 1368 or 1377), whose report on Malabar covers the 1340s, does not mention any mawlid ceremonies in Malabar (Ibn Baṭṭūṭa 1879, 4:71–111).2 Likewise, the most recent study on Islam in Malabar (Prange 2018) makes no mention of any mawlid practices. Hence, it is the mawlid texts themselves that form our main source to investigate the advent of the mawlid genre in Malabar. This situation requires a twofold approach. First, I seek to identify mawlid books and mawlid authors that moved between the Arab lands and the Malabar Coast; and second, I examine the literary features of mawlid texts, addressing the question what a mawlid text is and how it works as a devotional practice. I argue that mawlid texts with a specific structure and style that was appropriate for liturgical reading formed a model for what is believed to be the first Arabic mawlid composition in Malabar.

As a first step into exploring Arabic mawlid texts in the South Indian context, the present study will focus on the Malabar Coast. Malabar as a region refers roughly to the southern West Coast of India, from Goa to Kanyakumari. Today, it belongs to the state of Kerala in South India. As a case study, I take two outstandingly popular Arabic mawlid texts, one from the Islamic West and one from Malabar. The first is Sharaf al-anām, a mawlid text that most probably stems from thirteenth-century Andalusia and travelled widely. Sharaf al-anām was apparently known in Yemen in the late fifteenth/early sixteenth century and is included in compilations of devotional texts in Kerala, where it is still performed in our days (63 Waka mawlid n.d.; Muneer 2015). The second text is Manqūṣ Mawlid, which was most likely composed in Malabar in the early sixteenth century. The composition is generally ascribed to Zaynaddīn ibn ʿAlī al-Maʿbarī al-Malībārī (d. 1522)3 and constitutes one of the most popular mawlid texts in Kerala today (Arafath 2018; Muneer 2015). Furthermore, both texts are commonly a part of compilations of devotional texts, therefore calling for a comparative analysis of the nature of such compilations in the different cultural and historical settings. Sharaf al-anām was chosen because of its wide circulation and popularity. Manqūṣ Mawlid marks an important chapter in the history of Arabic literary production in Malabar because it is considered its earliest mawlid composition and it is traditionally linked to the Portuguese occupation. The examination of both texts shows that mawlid was known in Malabar prior to the sixteenth century, or, more precisely, Arabic mawlid texts were known, which clearly shows in Manqūṣ Mawlid. The composition of Manqūṣ Mawlid proved to be quite successful and, granted that it was the earliest composition, triggered several other Arabic mawlid compositions in the region (see examples in 63 Waka mawlid n.d.).

Arabic and Islam across the Indian Ocean

Islam in the Indian Ocean evolved in various frameworks. The most eminent is trade, more precisely maritime trade networks. In addition, networks by followers of the mystical path, or Sufis, emerged. Finally, migration played a major role in establishing Muslim communities, especially migration from South Arabian regions, most prominently from Hadramawt, but also the Tihama region facing the Red Sea (Ho 2006; Pearson 2011; Ricci 2016). Sure enough, such networks are not to be understood to operate separately but were often overlapping and intertwined.

Within these networks of trade, mysticism, and migration, there was another web at work, which Ronit Ricci has termed “literary networks” (Ricci 2016, 1–4). Researching Islam in South and Southeast Asia, she identifies the Arabic language as a major player, similar to the role Sanskrit had played in the centuries before (300–1300 CE):

In South and Southeast Asia both Sanskrit and Arabic have served, in closely parallel ways, as generative cultural nodes operating historically in conflated multilingual, diglossic, and “hyperglossic” environments. […] For Muslims worldwide Arabic possesses a unique status among languages. It is considered the perfect tongue by which God’s divine decrees were communicated to His Prophet. […] The Muslims in South and Southeast Asia proved no exception in their reverence toward the Arabic language, as they set up institutions where it could be studied, adopted its script to their own languages, borrowed its religious terminology and everyday vocabulary, prayed in it, and embraced its literary and historical narratives and forms. As a result, when I consider an Islamic cosmopolitanism in these regions, Arabic features as one of its major elements. (Ricci 2016, 14)

Ricci has coined the term Arabic Cosmopolis for the Muslim cultures in South and Southeast Asia where Arabic was not only a player in language contact but a tool of religious contact and ritual transfer. With the Arabic Cosmopolis she expands upon the Sanskrit Cosmopolis, a concept developed by Sheldon Pollock in the course of several articles and his monograph The Language of Gods in the World of Men (2006) (see Ricci 2016, 13–20, on differences in the social role of both languages, 14-15). Whereas Ricci focusses on Arabicised rather than Arabic literary culture, I intend to focus on Arabic texts that were adopted and re-appropriated by Muslims living in Malabar.

The present paper constitutes a first step in an attempt to contribute to emerging scholarship on Arabic literary production along the Malabar Coast and beyond to the eastern regions of the Indian Ocean Littoral. Yasser P.K. Arafath (2018, 7–8) states that only a few Arabic works from Malabar have been explored as sources for historiography, whereas a large part of Arabic writing from the fields of jurisprudence (fiqh), poetry (qaṣīda), preaching and exhortation (khuṭba, tadhkīr) by local Malabar scholars virtually remained terra incognita in Indian Ocean historiography. The present study deals with mawlid, a composition narrating the birth of the prophet and designed for performance, thus constituting a genre that comes from the field of both poetry and liturgy. Mawlid has been marginalised twice in Arabic and Islamic Studies.4 Since mawlid and the practice to commemorate or celebrate the prophet’s birthday does not belong to the obligatory core of Muslim ritual and emerged only a few centuries after the prophet’s death, it was often considered a popular devotional practice and thereby as secondary, especially in early scholarship, which was searching for an Islamic ‘essence’ and for ‘origins’ (Graham 1983). Second, its study has been neglected because the emergence of mawlid as text and practice coincided with the period that was considered as a period of decline (inḥiṭāṭ) in Arab culture and especially Arabic literature.5 As for the Malabar context, mawlid has likewise been excluded in studies on Malabar Muslim literary culture, a choice that was seemingly overshadowed by theological or, more often, ideological dispute on conformity and deviancy in Muslim ritual (Muneer 2015, 9).

The Malabar Coast shared features typical of other coastal regions in the Indian Ocean, such as the Swahili coast, the coast of Sri Lanka, or the Coromandel Coast, in being outward looking, international, and cosmopolitan. Moreover, its main export commodity, pepper, was a highly desired good in both Europe and China. The region thus was not only integrated into global trade, with Arab merchants as an important player, but became a destination for European merchant fleets in the early modern period.

The situation of Muslims in Malabar differed from Muslims in the North in various aspects. Though early Muslim-Hindu contacts in form of trade alliances are documented, Muslim influence did not exceed beyond the coastal region, and it is not before the thirteenth century that we can speak of a sizable Muslim permanent population (Pearson 2011, 330–31). Unlike the Muslim sultanates in the North, such as the Delhi Sultanate (since 1206) and the Mogul Empire (since 1526), which emerged as powerful geopolitical forces in the region, Muslims in Malabar never seized a territory. Malabar Muslims remained the subjects of Hindu rulers, in particular the Zamorin of Calicut who were praised as benevolent patrons of Muslims (e.g., Zaynaddīn II (Aḥmad Zayn ad-Dīn al-Maʿbarī al-Malībārī) [1405] 1985, 206) and the Rajas of Kochi. In the period the present paper deals with, roughly from the thirteenth to the early sixteenth century, North India was ruled by Muslim dynasties which were largely Ḥanafī and Persianate, whereas coastal Muslims were Arabicised and Shāfiʿī.6

The Malabar Muslim community comprised Muslims ‘from outside’ (paradesi), a heterogenous group of mainly Arabs from different regions as well as Persians and Turks, and local Mappila. This backdrop is of relevance for the assessment of literary networks, since it tackles a multi-religious and multi-lingual situation.7 The growth of the Muslim community was fostered by immigration from Hadramawt in the thirteenth century, which included many religious authorities, namely scholars and sayyids who trace their lineage back to the prophet (Ho 2006; Pearson 2011, 329). Furthermore, a change in long distance trading patterns from the end of the thirteenth century on caused social changes. The end of a direct route between Baghdad and Canton (Guangzhou) led to the rise of several port cities, and especially Calicut became a major trade node. As a result, the Muslim presence became more settled. Arab merchants who had only spent longer sojourns abroad or regularly travelled home for domestic affairs established permanent settlements (Pearson 2011, 322, 330–31).

With the advent of Vasco da Gama in Calicut in 1498, Portuguese-Muslim trade competition and wars started. Trade and travel became more difficult and dangerous but did not stop, and Muslims continued to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca and to study abroad (Kooriadathodi 2016, 209). In parallel, we witness a growth of local centres of learning, which deepened the Shāfiʿisation of the region (Arafath 2018; Kooriadathodi 2016). Such stages in the development of Muslim communities in Malabar, which have been mainly analysed in terms of migration, socio-economic changes, and jurisprudence (Ho 2006; Kooriadathodi 2016; Prange 2018), become tangible in religious practices and literary production, which the present study aims to show with the example of mawlid.

I start my analysis with a brief introduction to the historical background of commemorating the prophet’s birthday and outline the general literary features of a mawlid text. The main part of the paper provides an in-depth description of the structure, content, and selected stylistic devices of Sharaf al-anām and compares these to Manqūṣ Mawlid. This comparison is for demonstrating that Manqūṣ Mawlid follows the genre conventions of Sharaf al-anām and similar mawlid texts, especially in terms of form and style. This part furthermore offers a comparative analysis of devotional text compilations (majmūʿa) from the Arab world and South Asia. The last part examines the social context of the emergence of Arabic mawlid composition in Malabar. The composition of Manqūṣ Mawlid is traditionally linked to the advent of Portuguese naval power and subsequent wars and threats. Such a link, I argue, draws upon transformations in the function of mawlid readings at that time, which had turned from the commemoration of the birth anniversary to more general functions and occasions. Special attention is furthermore paid to the role of language and language experience which might have contributed to the emergence of a new poetic religious genre in Malabar, the māla.

The Context of mawlid Texts: A Very Short History

The Arabic lexeme mawlid denotes either the event, place, or date of birth; it can furthermore denote the commemorative celebration of the birth, or the aesthetic forms related to such a commemorative event. For instance, in his description of Mecca, the Andalusian traveller Ibn Jubayr (d. 1217) clearly relates to the place of the prophet’s birth and not to the date or celebration: “Another blessed site in the city is the birthplace of the prophet (mawlid an-nabī)” (Ibn Jubayr 1959, 91). In his lifetime—he visited Mecca in 1183/4 –, the place was opened for visitors on Mondays in the month Rabīʿ al-awwal of the Islamic calendar, as the prophet was believed to be born on a Monday in Rabīʿ al-awwal (Ibn Jubayr 1959, 92). Writing roughly at the same time, using the lexeme mawlid, the Egyptian official Ibn aṭ-Ṭuwayr (d. 1220) refers to the time and the event in his description of ceremonies in Fatimid Cairo (Ibn aṭ-Ṭuwayr 1992, 217). Arabic legal and historiographical texts use the term mawlid interchangeably for the date, anniversary, observation, or festive celebration, so that the meaning must be derived from its context each time. Mawlid is furthermore often used as the short form for mawlid an-nabī (the prophet’s birth), and it is in this sense I will be using the term here. Throughout this article, only texts on the prophet Muḥammad’s birth are discussed.8

The terminology for text and event commemorating the prophet’s birth furthermore varies locally. In contemporary Kerala, the term mawlūd, which in Arabic designates the newborn, is far more widespread than mawlid (Muneer 2015, 1–2, 10). In Bangladesh, mīlād (birth) is the common term;9 in Egypt, it is mūlid (a variant of mawlid in the spoken language), and in Turkey mevlit, mevlût, or mevlüt (also with final /d/). All terms are derived from the same Arabic root, w-l-d (to give birth).

The practice of commemorating the prophet’s birthday as a public event is a rather late development in the history of Islam. Judging by the current state of research, there is no linear development of a ritual practice termed “mawlid.”10 As Marion Katz (2007, 2019) rightfully points out, there are quite different ways of observing the anniversary of the prophet’s birth. Any history of the practices connected to the prophet’s birthday needs to take account of differences between the observance of the day, for instance by individual fasting, and various forms of the day’s communal ritual elevation, furthermore between private and public celebrations, and between assemblies with and without the public reading of literary texts written on the occasion of his birth. For the purpose of the discussion in this paper, I list some basic developments in order to give the wider context of the texts under study.

Early forms of piety that might be of relevance for later mawlid practices are found in the Imāmī Shiite traditions of narratives on the birth of the prophet and his close relatives and in the observation of their birth anniversaries through fasting, almsgiving, and rejoicing. Such practices are mentioned by authors of the tenth and eleventh century, unfortunately with very little details (Katz 2007, 3–5). The Fatimids in Egypt introduced mawlid commemorations as a state-sponsored event to emphasise their legitimation as a ruling dynasty. They thus celebrated not only the birth of the prophet Muḥammad, but also of his daughter Fāṭima, his son-in-law ʿAlī, of the ruling caliph, and in some years also of the prophet’s grandchildren Ḥasan and Ḥusayn. The introduction of the Fatimid mawlids can be dated roughly to the mid-eleventh century (Kaptein 1993, 23–24; Lev 1991, 146–47).

For the second half of the twelfth century, we have sporadic references to mawlid celebrations in Syria and Iraq. The observance of the prophet’s birthday by a pious figure named ʿUmar al-Mallāʾ in Mosul that was attended by members of the local elite constitutes a semi-official type of celebration. It was marked by the recitation of poetry praising the prophet (Kaptein 1993, 35). There are furthermore indications for the observance of mawlid by the Zengid ruler Nūraddīn (d. 1174) in Aleppo (Kaptein 1993, 31–34). The huge celebrations on the occasion of the prophet’s birthday organised by the Begteginid ruler Muẓaffaraddīn (r. 1190–1232) in Irbil are, in contrast to the events mentioned before, very well documented. The most famous description is included in the biographical dictionary by Ibn Khallikān (d. 1282), which allows us to date the yearly celebrations to the end of the twelfth/beginning of the thirteenth century [Ibn Khallikān (1990), 3:449-50; 4:117-19]. The celebrations span over a period of several weeks and included banquets, sermons, processions, recitations, the distribution of presents, and various forms of entertainment.

In the Muslim West, the ʿAzafid rulers in Ceuta introduced mawlid celebrations in the first half of the thirteenth century; rulers of other local dynasties in North Africa and Andalusia followed from the mid-thirteenth century onwards (Brown 2014; Kaptein 1993, 76–140). As becomes clear from the sources analysed by Kaptein (1993) and Shinar (1977), the venues of mawlid festivities ranged from court celebrations to public places, Sufi lodgings, schools, and private homes. Besides the recitation of literary compositions written for the occasion, festivities included various elements of ritual (e.g., fasting, Quran recitation) and entertainment (e.g., horse racing, musical performances). Thus, by the late thirteenth century, the observance of the prophet’s birthday had become a widely established practice marked by public celebrations on a wide scale and in different geographic regions.

It should be noted that this new occasion for celebration did not remain undisputed among Muslim scholars. Moreover, the answer to the question whether the celebration of mawlid was an approvable innovation or not was rarely a simple Yes or No (as today’s dichotomic treatment of many subjects would suggest). Rather, it was often a conditional Yes, evaluating the different aspects and practices in observing the prophet’s birthday separately. The tenor of many statements was that the observation of the day was not objected to, given the fact that it was observed to honour and thank God and the prophet and that it was not accompanied by any unlawful activities. To feed the poor or have the Quran recited on that day was deemed a meritorious act even by sceptical scholars like Ibn al-Ḥājj (d. 1336–37) or Ibn Taymīya (d. 1328). Both nevertheless expressed their reservation and feared people would understand the observation of the prophet’s birthday as an obligatory duty or treat it like a canonical feast (ʿīd). Mawlid frequently became an object of legal opinions (fatāwā, sg. fatwā), dealing with various aspects of its celebration, such as what gifts to bring or the legitimacy of including money for mawlid celebrations into a pious endowment (waqf). An often-quoted classic is the lengthy fatwā by the Egyptian polymath Jalāladdīn ʿAbdarraḥmān as-Suyūṭī (d. 1505), who discusses the pros and cons by many other scholars before giving his conditional licence.11

Mawlid as a Transcultural Genre

Roughly at the same time when the practice of observing mawlid in public celebrations on a wide scale developed, a new type of text emerged in the Arabic-speaking world whose literary features persisted until the twentieth century. These texts centre on the birth of the prophet Muḥammad and the occurrences which preceded, accompanied, and followed his birth: the various signs that happened during pregnancy and birth, the search for a wet-nurse, and episodes from his childhood and youth. On a formal level, the texts combine prose, rhymed prose, and poetry. Today’s prints of the most popular texts have approximately 40 pages, which means they can be easily recited in one session. Such texts seem to form a literary genre whose name is taken from the main event they describe: the birth of the prophet, i.e. mawlid.

Katz (2007, 2019) is right to emphasise that texts that describe the birth and life of the prophet precede the communal public mawlid celebrations. However, the specific textual genre I am describing here emerged when celebrating the prophet’s birth became established on a wide scale. The newly emerging mawlid texts do not differ much in content from the preceding ones, but rather in form, and these formal characteristics allow us to speak of these texts as a genre of its own (Katz 2007, 50, 2019, 168).

The mawlid genre, to my mind, offers a rich perspective for exploring the transcultural circulation of Arabic texts and the religious practices connected to these texts. This genre soon spread beyond the Arabic-speaking world, where mawlid texts became recited and composed in Arabic as well as other languages. First, we find Arabic texts from the Western and Eastern Arab regions recited outside the Arabic-speaking world: the text Sharaf al-anām is widely used in South India (Kerala)—but also in Malaysia, Indonesia, Kenya, Tanzania, or Somalia (Knappert 1988; Muneer 2015; evidence by manuscripts from different regions, see n. 14). Thus, Sharaf al-anām can certainly be termed a “traveling text.” Since the late nineteenth century, it also travelled as a book in print: Jan Knappert (1988, 212) notes its first edition was printed in c. 1885 by the publishing house of a certain Sulaymān Marʿī located in both Singapore and Aden.

Second, we find translations from Arabic into other languages: for instance, the mawlid composed by the Shāfiʿī mufti of Medina, Jaʿfar ibn Ḥasan al-Barzanjī (d. 1764), has been translated into Indonesian and Malay languages (Knappert 1988, 213). Third, mawlid texts were newly composed in Arabic outside the Arab world, for instance by Malabar Muslims in Kerala: The Manqūṣ Mawlid, generally ascribed to Zaynaddīn ibn ʿAlī al-Maʿbarī al-Malībārī, serves as a prominent example. This case in point constitutes an example for a “traveling genre.” Forth, mawlids have been composed in other languages, such as the famous mawlid in Ottoman Turkish by Süleyman Çelebi (d. 1421)12. Hence, the mawlid is a highly transcultural phenomenon that moves between different regions and languages.

Mawlid as a Text: Structure and Formal Characteristics

The following brief characterisation of mawlid texts draws from the evaluation of a sample of about 30 mawlid texts which were composed between the thirteenth and eighteenth century and which cover a geographical span from Andalusia in the West to Yemen in the East. Only a small number of mawlid texts is available in scholarly editions; rather, texts mainly circulate in inexpensive leaflets. For my research on formal characteristics, I heavily rely on manuscripts. The evaluated texts share several common features which will be briefly summarised.

A mawlid text is usually prosimetric, that is, it combines poetry and prose, as many pre-modern texts in Arabic literature do. A strict separation of genres written entirely either in verse or in prose did not prevail before the nineteenth century (Heinrichs 1997, 249; Reynolds 1997, 277). The Arabic language furthermore knows a third mode of speech, termed sajʿ. Sajʿ, generally translated as “rhymed prose,” designates speech units of different length with no metre, but with a rhyme at the end. All three modes, poetry, prose, and sajʿ, are combined in Arabic mawlid texts.

A mawlid text contains several episodes from the life of the prophet, framed by an introduction and a concluding supplication (duʿāʾ). The introduction usually is in highly ornate speech, featuring praise of God and successively of Muḥammad. The single episodes on the prophet’s life are often preceded by reports on God’s creation and/or the prophet’s genealogy. The focus of mawlid texts lies on Muḥammad’s birth and episodes from childhood and youth. Many texts end here, and if they go further, they only briefly mention events that happened after the prophet’s first marriage with Khadīja (see also Katz 2007, 55). A great part of the poems figure praise of the prophet; in addition, a considerable number of poems is interwoven into the narrative line, featuring the prophet’s grandfather as a speaker or addressing his mother Āmina.

Poems are rarely longer than 20 lines, and occasionally only two or three verses are inserted into the text. Much of the poetry is in the qaṣīda form with a mono-rhyme (on qaṣīda, see also below). A considerable amount of poetry, though, is in strophic forms (muwashshaḥ, mukhammas), which are apt for singing, or poems provide different types of refrains by which listeners are able join a solo performer. In addition, texts repeatedly feature an invocation of blessing for the prophet (taṣliya) which may take on an embellished form in rhyming couplets or quatrains.

Though all examined texts share this general structure, there are also differences. Mawlid texts vary in length, in the amount of poetry used, and in the density of the rhetoric devices that are employed to beautify the text. Some texts contain long passages in plain prose; other texts are careful literary compositions with only a minimum of non-ornate prose. Mawlid texts also vary in content: some texts show close conformity with the scholarly established biography of the prophet (sīra)13 and build on material from the Quran and Hadith. Other texts include motifs and reports that circulated outside of these sources and are in parts present in later compilations on the prophet’s extraordinary qualities and the signs of his prophethood (i.e., books on khaṣāʾiṣ, shamāʾil, and dalāʾil).14 In addition, some authors added lengthy explanatory passages on single motifs or events into the narrative. Further literary features of a mawlid text shall be exemplified through the example of a highly popular text: the abovementioned Sharaf al-anām.

Mawlid as Part of a Compilation (majmūʿa) of Devotional Texts

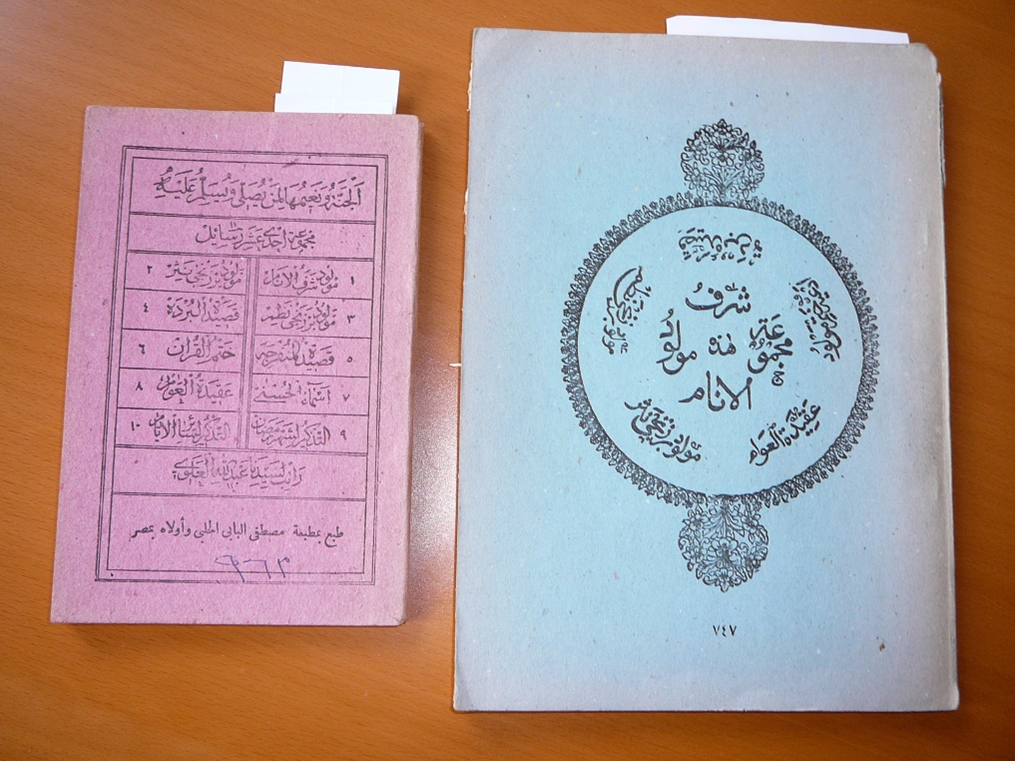

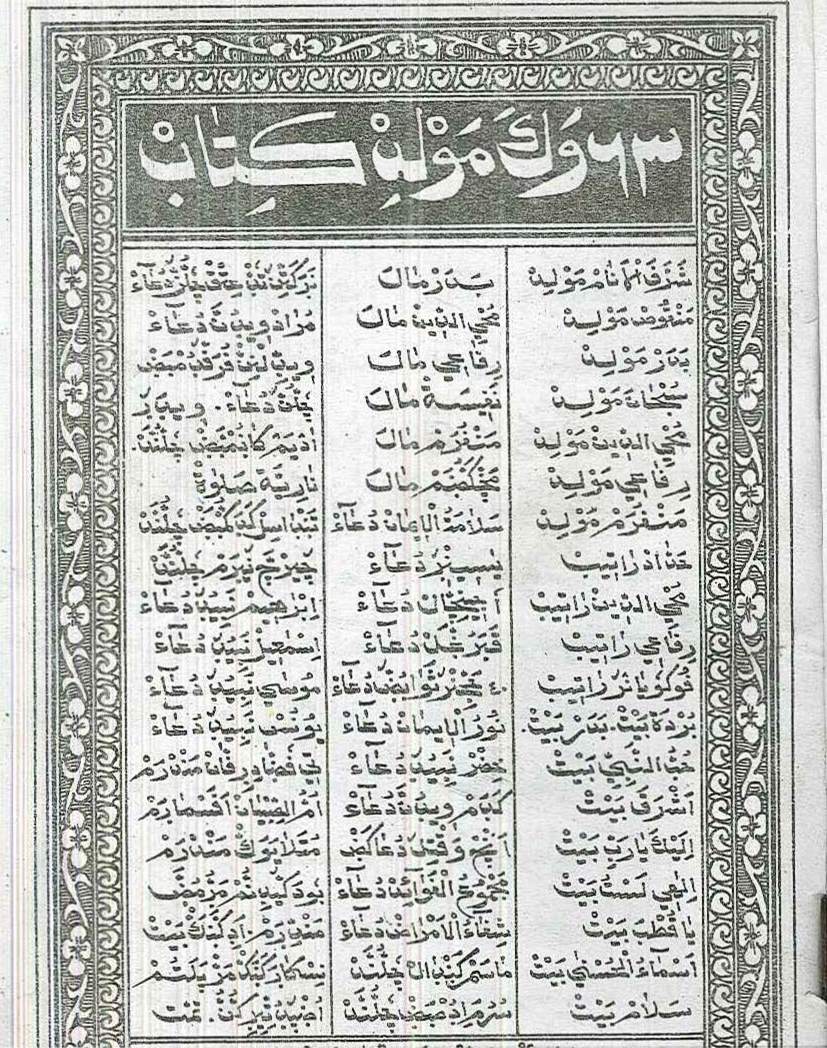

To compile more than one text into a single manuscript was a common phenomenon in the Arabic-Islamic tradition of learning. The majmūʿa, thus, is by no means a modern phenomenon or limited to printed books. Gerhard Endress (2016) differentiates between composite manuscripts which originally had been separate codicological units that later were bound by a bookseller or librarian and multiple-text compilations that had been written and organised by one scribe. Both are called majmūʿa (“collected”) in Arabic, and the texts included in such a majmūʿa can comprise quite different fields of knowledge. Likewise, the practice to organise different devotional texts into one manuscript or print includes other genres besides the mawlid. In the following, I will present the content of some contemporary compilations from West and South Asia. In a number of these, the title page has the function of a ‘table of contents’, as it announces the different texts included into the book: Illustration 1 shows the title of a compilation from Cairo (left, this is example No. 1 in Table 1 below) and a second one without printing place (right). Though different from the outlook, the content of both books is almost identical. Figure 1 shows the content of a compilation from Thirurangday, Kerala (example No. 3 in Table 1 below).

Table 1 shows the content of three selected compilations in a table. The first example is an undated print from Cairo that, by name of the publisher and visual appearance, can be dated roughly to the first half of the twentieth century (Majmūʿat iḥdā ʿashara rasāʾil, n.d.).18 The second one was compiled by a private person and uploaded as a pdf file on the internet (Mawlid kitab, n.d., see also below). It contains only Arabic texts, but additional information is given in Malayalam, which indicates a Kerala provenience. The third example was printed in Thirurangady, Kerala, and contains devotional texts in both Arabic and Arabic Malayalam (63 Waka mawlid kitab, n.d.).19 All three compilations prominently feature the mawlid text Sharaf al-anām.

| Majmūʿat rasāʾil (No 1) | Mawlid kitāb (No 2) | 63 Waka mawlid (No 3) |

|---|---|---|

| Sharaf al-anām | Yā akram bayt | Sharrafa l-anām mawlid |

| Mawlid al-Barzanjī (both) | Sharaf al-anām mawlid | Manqūṣ Mawlid |

| Qaṣīdat al-Burda | Manqūṣ Mawlid | More mawlid texts from South India |

| More poems | Mawlid Badr | Several rātib texts, including Ḥaddād |

| Khatm al-Qurʾān | Qaṣīdat al-Burda | Burda bayt |

| Prayers and litanies | Poem praising Khadīja | More Arabic poems (bayt) |

| Rātib ʿAbdallāh al-ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād | Several māla texts | |

| Several duʿāʾ |

What are the other texts that are typically combined in such compilations? Yā akram bayt is the last part (vv. 152-160) of the Mantle Ode (Qaṣīdat al-Burda), an ode in praise of the prophet Muḥammad composed by the Egyptian poet Sharafaddīn Muḥammad al-Būṣīrī (d. 1294–97). According to tradition, the poet, after composing and reciting the ode in order to seek the prophet’s intercession and God’s forgiveness, fell asleep and saw the prophet in his dream, covering him with his mantle (burda). Thus, the ode was called Mantle Ode, or Burda. The title Yā akram bayt is derived from verse 152 that starts with Yā akrama r-rusli (Oh best of [all] prophets), addressing Muḥammad (1955, 200–201).20 The Mantle Ode was already famous for its assumed auspicious power during the lifetime of the poet, and it features in numerous compilations of devotional texts as well as in stand-alone prints and manuscripts. The opening verses of example No. 2 are combined with a seven-verse prayer that is commonly added to the performance of the Burda.21 The complete Burda poem is included in all three compilations.

The Arabic term qaṣīda can denote any poem in a general sense. Yet, qaṣīda is also the technical term for a type of poetry that needs to meet certain formal criteria. In this narrower sense, qaṣīda designates a polythematic, non-strophic poem with mono-rhyme and in one of the 16 metres codified as ‘classical.’22 This type of poetry is documented from the sixth century onwards and is still composed today. It is also the main form of praise poetry for the prophet Muḥammad (al-madīḥ an-nabawī), the Burda being one of its most prominent examples. Bayt in Arabic denotes a poem’s single line, which in the qaṣīda form consists of two hemistichs. In the South Indian context, the Muslim Arabic poetry that builds on the formal features of Arabic poetry is called bayt. In our examples from Kerala, bayt and qaṣīda are used interchangeably: in example No. 2, the complete Burda is termed Qaṣīdat al-Burda, whereas in example No. 3, it is termed Burda bayt.

Example No. 3 includes a second poetic genre, the māla. Māla is the technical term for poetry composed in Arabic Malayalam and dedicated to eminent Muslim figures (on māla, see also below). Arabic Malayalam, that is, Malayalam written in an adopted Arabic script, can be traced to the early seventeenth century, the famous Muḥyīddīn Māla composed by the Shāfiʿī scholar Qāḍī Muḥammad (d. 1616) (Arafath 2020, 2) being its most prominent example. The Muḥyīddīn Māla is a long poem in praise of the Ḥanbalī scholar ʿAbdalqādir al-Jīlānī (d. 1166) who is venerated as a Sufi and reviver (muḥyī) of religion. Composed in 1607, it is generally considered the first written evidence of this language amalgamation and combines the Arabic poetic tradition with polyglossic Malayalam and the Dravidian literary tradition (Arafath 2020; Gamliel 2017).

Khatm al-Qurʾān, which features in example No. 1, is a type of prayer (duʿāʾ) performed after the complete recitation of the Quran. In contrast to the ritual prayer (ṣalāt), which in its prescribed liturgical form comprises various verbal and bodily acts, the performance of duʿāʾ is without prescriptions in terms of time, text, or body movements. Texts may be chosen from the Quran, from the prophet’s example, or individually composed. Rātib either denotes supererogatory ritual prayer (ṣalāt) or, here, litanies recited alone or in groups. Rātib ʿAbdallāh al-ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād thus is a litany ascribed to ʿAbdallāh al-ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād (d. 1720), a Sufi poet from Yemen.23 Example No. 3 includes rātib ʿAbdallāh al-ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād, too, as well as several other rātib texts ascribed to prominent Muslim scholars.

Plentiful Arabic compilations that I have documented in the course of my research are similar to the described examples. For the Southeast Asian context, two other compilations described in the research literature can be added here. The text of Sharaf al-anām that Nawwāl Abū l-Fatḥ (1995) used for her study is a reprint from a compilation published in Jakarta. Besides Sharaf al-anām, it includes both mawlid texts of al-Barzanjī, the mawlid by the aforementioned Ibn ad-Daybaʿ, the mawlid by the nineteenth-century scholar from Medina, Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-ʿAzab (GAL S II, 815), the Mantle Ode by al-Būṣīrī, and several prayers, including one to be recited after a mawlid and one to be recited after the complete recitation of the Quran (Abū l-Fatḥ 1995, 2:255). The content of the aforementioned compilation from Singapore and Aden as given by Knappert (1988, 212–13) comprises both mawlid texts by al-Barzanjī, the Mantle Ode by al-Būṣīrī, a prayer (duʿāʾ) to be read after a mawlid recitation, another one to be recited in the Mid-Shaʿbān night,24 and two condensed versions of the main Muslim doctrines. Thus, the typical genres included in such compilations that feature Sharaf al-anām are, next to mawlid, praise poetry (qaṣīda, bayt, māla), litanies (rātib), and prayers, most typically prayers that conclude the recitation of mawlid or the Quran.

Such compilations of devotional texts were printed in publishing houses like the one founded by the al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī family in Cairo in 1859 and specialised in publishing the Arab-Islamic heritage. Moreover, compilations as well as single mawlid texts were often printed on behalf of and financed by individuals. A considerable number of texts that I collected and a large number of texts included in Abū l-Fatḥ’s study bear such an indication, usually in the form of a short notice on the cover or the back of the print. To compile and/or finance the print of devotional texts is considered a religiously meritorious act. We can conclude that the texts gathered in such collections were either popular and in demand or considered as useful by a single person. A recent example is the compilation of mawlid texts and poems that has been uploaded on the internet as a pdf file (example No. 2). The compiler expresses his hope that somebody would put it into print (Mawlid kitab, n.d., 72).25

Mawlid as a Practice

From the fourteenth century onwards, we find indications that mawlid texts were publicly recited (Katz 2007, 56, 72, 82, 2019). “Publicly” means they were read in front of an audience; the venue could be a private home, a mosque, or a zāwiya (place of a Sufi congregation). The occasion for such a recitation was the commemoration of the prophet’s birth in the respective season, i.e., roughly the first half of the month Rabīʿ al-awwal, the third month of the Islamic lunar calendar.28 By the late fifteenth century, mawlid recitations had become common practice during other times of the year as well, detached from the birth. The communal mawlid reading—comprising not only the recollection of the prophet’s birth but also praise of the prophet and the invocation of blessings for the prophet—had gained the status of a religiously meritorious act. Readings were held on occasions that would call for gratitude or ask for God’s blessings, such as an engagement, a wedding, or a boy’s circumcision (Katz 2007, 72–73, 2019).

Today, large parts of the mawlid are recited in a responsorial manner between a solo reciter and a group. At least the invocation of blessings for the prophet (taṣliya) is performed by all participants of the occasion.29 The question of historic practices demands further research. A detailed reconstruction of historic recitation practices is difficult and, in many respects, impossible. Nonetheless, there are indications that the communal—and audible—performance of invocations of blessings for the prophet was part of a mawlid reading also in historic times. The Syrian poetess ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūnīya (d. 1516) witnessed a mawlid reading during her pilgrimage stay in Mecca around 1475 and she reports: “It was Friday night, and I reclined on a couch on an enclosed veranda overlooking the holy Kaʿbah and the sacred precinct. It so happened that one of the men there was reading a mawlid of God’s Messenger, and voices arose with blessings upon the Prophet” (ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūnīya, quoted in Homerin 2013, 130–31).

Occasionally, we find the invitation to invoke blessings for the prophet included in manuscripts, and for many prints, it has become standard to include it. Such an invitation to invoke blessings can take various forms, ranging from a short formula (commonly ṣallū ʿalayhi wa-sallimū taslīmā) to embellished rhymed verses.30 Hence, the performance of a mawlid text is not limited to a solo reciter but involves the audience, who become active participants in the event by uttering the invocation. Equally, the taṣliya is more than an automated response to the mention of the prophet. Muslim scholars considered the inclusion of the taṣliya as the most appropriate way to articulate a supplication and furthermore as a tool to increase its potential answer (Meier 1992). As mentioned above, a mawlid reading was not only a way to commemorate the prophet’s birthday but was carried out to express gratitude or joy, or to ask for support. Against this backdrop, the communal performance of the taṣliya within a mawlid reading is marked by polyvalence; it works as a participatory element to include the listeners, it is conceived as a means to ensure the efficacy of a supplication, and it constitutes a reward-wining act in itself (Katz 2007, 81–83; Weinrich 2016, 123–24).

Further ritual elements related to mawlid texts include the practice to stand up when the reciter reaches the event of Muḥammad’s birth (qiyām). This practice is generally traced back to an event in Damascus and two lines of a praise poem by the thirteenth-century author Yahyā ibn Yūsuf aṣ-Ṣarṣarī (1989, 53):

It is not enough to praise the Chosen One [i.e. Muḥammad] by writing in golden letters / on silver in best script

Nor is it enough that the noble men when they hear it / stand up in lines or fall on their knees

The prominent Mamluk scholar Taqīddīn as-Subkī (d. 1355) once attended a full recitation of the Quran in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. When he heard these verses recited during the event, he got up and stood, and the men around him did the same. This incidence, reported by his son Tājaddīn as-Subkī (d. 1370), generally is named as the first standing in honour of the prophet (Katz 2007, 128–29; Kayyāl 1984, 120). In the mid-sixteenth century, we find writings that confidently defend the practice of qiyām during mawlid recitations against critics. This suggests that it was an established practice by that time (Katz 2007, 129).

Closely connected to the practice of qiyām are verses in the form of ‘welcome-songs’: passages of poetry which directly address the prophet, like “Welcome, oh Light of My Eyes” (Marḥaban yā nūr ʿaynī) or “O Prophet, peace be upon you” (Yā nabī [alternately: Yā rasūl] salāmun ʿalayka). There is reason to assume that these verses were in many cases later additions, since especially popular verses migrated between different mawlid texts and are also included independently in compilations of devotional texts (63 Waka mawlid kitab, n.d., 145–46; al-Barzanjī 2008, 134; Katz 2008, 273; Muneer 2015, 13; Salakidis 2018, 347). Today, such verses are commonly chanted by all participants. Mawlid recitations seem to have ended regularly with a supplicatory prayer (duʿāʾ). Commonly, the prayer addresses general petitions for wellbeing, health, the prophet’s intercession, and God’s forgiveness. Many texts, both in manuscript and in print, include such a prayer. Depending on the ritual practices of the respective communities, this prayer may be accompanied by bodily acts, such as standing or raising the arms or hands.

Further practices related to mawlid readings varied according to time and space and will be mentioned only briefly. Accompanying activities include decorating the place and the burning of scented wood or incense during the reading. People not only express their plea for God’s blessing and his forgiveness through organising and financing a mawlid reading, but they can take part in the economy of gifts and rewards by being responsible for single elements of a mawlid performance, such as providing food, scented water, or sweets that are distributed during a reading (Katz 2007, 63–103; Kayyāl 1984, 121, 123; Muneer 2015, 15).

The Arabic mawlid in Transcultural Perspective

The immensely wide distribution of compilations, both in print and as manuscript, of the majmūʿa-type containing Sharaf al-anām as well as stand-alone copies of Sharaf al-anām suggests the text was well known in the Arab lands and beyond. Interestingly, Katz (2008, 474) notes that Sharaf al-anām is very popular in contemporary Yemen and that its popularity there is historically rooted. The remark by the aforementioned scholar Ibn ad-Daybaʿ (d. 1537) that he finally identified the author of Sharaf al-anām indicates that the text was known during his lifetime in Yemen. ʿAbdalqādir ibn Shaykh al-ʿAydarūs, who informs us about this, further adds the remark that he heard “many people” ascribing the text to the Ḥanbalī scholar ʿAbdarraḥmān Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 1200) instead. This remark supports the assumption that the text Sharaf al-anām was widespread, since “many people” talk about it (al-Aydarūs 2001, 292). A link between Yemen and India is not only provided by the ʿAydarūs family but, though indirectly, by Ibn ad-Daybaʿ. Ibn ad-Daybaʿ, with the full name ʿAbdarraḥmān Ibn ad-Daybaʿ az-Zabīdī, was a Shāfiʿī scholar and historian who spent most of his life in his hometown Zabīd in the Tihama during the reign of the Ṭāhirid dynasty in Yemen. Ibn ad-Daybaʿ’s father migrated to India (“bilād al-Hind”). He never met his father, but news and money travelled between both regions, since he inherited a small sum of money from his father which he spent for his first pilgrimage in 1479. In 1491, following his third pilgrimage, he studied in the Hijaz with the renowned Egyptian scholar Shamsaddīn Abū l-Khayr Muḥammad as-Sakhāwī (d. 1497). Among Ibn ad-Daybaʿ’s historic works that survives is a history of his native town under the title Bughyat al-mustafīd fī akhbār madīnat Zabīd.31 It describes a mawlid celebration under the Ṭāhirid ruler al-Malik al-Manṣūr in 1485 and mentions that a mawlid reading (qirāʾat mawlid an-nabī) was ordered (Ibn ad-Daybaʿ 1983, 165). This shows that mawlid reading was practiced in Zabīd already before he met as-Sakhāwī, one of the most prominent proponents of mawlid. It nevertheless does not exclude the possibility of as-Sakhāwī having an impact on a positive attitude towards mawlid writing among Arab as well as South Asian scholars in his teaching circles. as-Sakhāwī wrote a mawlid text that unfortunately only survives in short quotations (Katz 2007, 78). Ibn ad-Daybaʿ’s own mawlid text is still popular today (Katz 2008; Knappert 1988, 214, interview with Shaykh Muṣṭafā al-Jaʿfarī, 24.06.2013 in Beirut).

The investigation of mawlid thus includes the traveling of practices, knowledge, and scholarly networks. If ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūnīya reported on a public reading of a mawlid in fifteenth-century Mecca, others must have heard such readings, too. The Hijaz constituted an important hub, as it was common that scholars and pilgrims spent long sojourns there either to teach or to study. Especially Mecca was a significant contact zone for Muslim scholars from West and East Asia. Ibn ad-Daybaʿ stayed there for a considerable period during his pilgrimage, as did ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūnīya. The Shāfiʿī scholar as-Sakhāwī repeatedly left his native city Cairo for pilgrimage and to spend time in the Hijaz for teaching and interacting with scholars from the Muslim East (Petry 1995).

In the case of Zaynaddīn ibn ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad al-Maʿbarī al-Malībārī (d. 1522), the presumed author of the Manqūṣ Mawlid, not only Mecca was a place of education. He travelled further to Cairo to study at the al-Azhar (Amer 2019; Kooriadathodi 2016, 211). Information on Zaynaddīn ibn ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad al-Maʿbarī al-Malībārī and his family is sparse and often conflicting. For the following short notes on his biography, I mainly use Amer (2019) and Kooriadathodi (2016, 209–12). Zaynaddīn ibn ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad al-Maʿbarī al-Malībārī (hereafter Zaynaddīn I) hails from a family of scholars that claims a Yemeni origin. In the fifteenth century, the family moved from the Coromandel Coast (Arab. al-Maʿbar, lit. the place where one crosses, namely Arab boats en route to China) to the Malabar Coast.32 The family first settled in Kochi, then in Ponnani. Zaynaddīn I received his first education in Malabar and then spent at least six years in Mecca from where he travelled to Cairo. Among his most prominent teachers in Cairo were Zakariyyāʾ al-Anṣārī, the Shāfiʿī mufti and later chief judge (qāḍī l-quḍāt), and as-Suyūṭī, the author of the abovementioned fatwā Ḥusn al-maqṣid fī ʿamal al-mawlid (The Good Purpose in the Observance of the mawlid). Upon his return to Ponnani, Zaynaddīn I worked as a teacher and jurist. He wrote several books on mysticism (taṣawwuf) and exhortation (waʿẓ), but also on grammar, jurisprudence, and theology.33 His most renowned work seems to be Hidāyat al-adhkiyāʾ ilā ṭarīq al-awliyāʾ (Guidance for the Bright to the Path of the Friends of God), a versified manual on Sufism, which was commented several times and widely studied far beyond Malabar.34

By the time of Zaynaddīn I—and partly owing to his activities—Ponnani had become an intellectual centre of the Malabar Coast. Through migration from the Coromandel Coast as well as from other parts of the Malabar Coast, the Muslim population in Ponnani had significantly grown in the second half of the fifteenth century. Immigration was intensified through Portuguese hostilities, when in the early sixteenth century Muslim merchant families left for Ponnani, especially from Portuguese-dominated Kochi (Kooriadathodi 2016, 210). With its newly established mosques and educational institutions, the city attracted many students and became the scene of a vibrant scholarly and ritual life, known as “Little Mecca” or “Mecca of South India” (Kooriadathodi 2016, 209). Students still travelled to Arab lands to pursue further education, but no longer to Cairo but to Mecca (Kooriadathodi 2016, 212). Zaynaddīn II (d. 1579),35 grandson and namesake of Zaynaddīn I, spent around ten years in Mecca, where he studied, inter alia, with Ibn Ḥajar al-Haytamī (d. 1567), an eminent Shāfiʿī scholar from Cairo who had resided permanently in Mecca since 1533 and was the author of several works on the mawlid (Kooriadathodi 2016, 196).36 Besides this, Ponnani became a place of learning for Muslims from Hadramawt, Sri Lanka, or Indonesia (Kooriadathodi 2016, 212).

Hence, by the sixteenth century, we can ascertain movements of knowledge networks in multiple directions, not only the typical arrows that have for a long time dominated in studies of cultural contacts, but also circles (Flüchter and Schöttli 2015). From the thirteenth century on, there is a strong movement from Yemen towards Malabar through emigration. Besides, pilgrims and students move from Malabar to the Hijaz and, eventually, Cairo and back again. By the sixteenth century, Mecca was the primary location of learning abroad for students from the Malabar Coast, and Ponnani emerged as a new place of education that attracted students from Hadramawt, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. It is not unlikely that Manqūṣ Mawlid was composed in such an environment and that mawlid texts such as Sharaf al-anām were known by Muslims in Malabar.

Perspectives on Re-contextualisation: Form, Function, and Language

I have shown that in structure and style, Manqūṣ Mawlid closely follows the form of early Arabic mawlid texts such as Sharaf al-anām or Mawlid al-ʿArūs. Further research will have to include other mawlid texts from Malabar and to look at potential changes in form, content, and functions, such as the transformations of imagery and poetic forms, the inclusion of material which is not found in examples from the Arab world, and other strategies of domestication, that is, strategies which inscribe texts “with linguistic and cultural values that are intelligible to specific domestic constituencies” (Venuti 1998, 67). At this point, I will only add two preliminary short remarks. Compared with mawlid texts from the Arab world, it is remarkable that in Kerala we find a variety of mawlid texts not only on Muḥammad but also on other Muslim figures that are relevant to the history of Islam in Malabar. These include Cheraman Perumal, a Hindu ruler and main protagonist of a number of origin narratives,40 and ʿAbdalqādir al-Jīlānī, the eponym of the Qādirīya order, who is not only honoured with the Muḥyīddīn Māla but also with a mawlid text (Mawlūd Tājaddīn al-Hindī al-Malībārī [1312] 1894; 63 Waka mawlid kitab, n.d., 40–47). There are also indications that mawlid as a term was used for texts that did not necessarily follow the structure of the early Arabic mawlid texts in Malabar. It seems that a larger variety in form and content of mawlid compositions from Malabar occurred only after the initial phase that is traditionally set with Manqūṣ Mawlid. We must leave these questions for future research and will continue with the context of the Manqūs Mawlid.

Arafath sees in the highlighting of Adam an individual accomplishment by Zaynaddīn I and the author’s strategy to strengthen Muslim identity and gather his Muslim fellows under this banner:

One important thing we can notice in Manqus is the narrative around the genealogy of Prophet Muhammed. In the height of Portuguese penetration in Malabar, Makdhum I (sic) [i.e., Zaynaddīn I] knitted together a long family history of Prophet Muhammed by genealogically connecting him to Adam, who, according to the Quran, was the first human and the first prophet. (Arafath 2018, 25)

In my view, the passage is rather owed to genre convention than an individual invention by a single author, since including the lineage of prophets back to Adam is common to most mawlid texts. In addition, the topos of Adam and the wandering light figures in numerous instances of praise poetry for the prophet (al-madīḥ an-nabawī) and in works on the prophet’s qualities from the twelfth century onwards (e.g., al-Būṣīrī 1955, 2 (verses 9-14 of the Hamzīya), 194 (verse 59 of the Burda); A. l.-F. ʿ. Ibn al-Jawzī, n.d., 1:70–71; al-Qāḍī Abū l-Faḍl ʿIyāḍ al-Yaḥṣubī, n.d., 1:166–67). It is likely that such works circulated among Malabar scholars as well. Zaynaddīn I was almost certainly acquainted with the Burda, since one of his teachers in Calicut, Fakhraddīn Abū Bakr ibn Qāḍī Ramaḍān ash-Shāliyātī (d. 1493), composed a poetic emulation of this ode in the technique of a takhmīs, that is, an amplification that adds three hemistichs to each line of the base poem, here the Burda (Muneer 2014, 270). Zaynaddīn I was furthermore well-acquainted with al-Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ’s work on the special qualities of Muḥammad, ash-Shifā bi-taʿrīf ḥuqūq al-Muṣṭafā, which contains a version of the light narrative, since he composed an abridgment (mukhtaṣar) of ash-Shifā (Kunhali 2004, 87n32; Zaynaddīn II (Aḥmad Zayn ad-Dīn al-Maʿbarī al-Malībārī) [1405] 1985, 12–13).

Nevertheless, this does not mean that the passage, together with the act of communal mawlid reading, did not function in the way Arafath describes. The advent of European naval power in 1498 brought dramatic changes for the different communities living in Malabar. Arafath sees the mawlid reading as a means to face the threats in early sixteenth-century South India, caused by war, diseases, and a new power.

Arab Muslims as well as local communities in the region were worried about a new religion, maritime distress, sea wars and new diseases such as syphilis, all of which came along with the Portuguese. Manqus endowed the Prophet as the ‘saviour man’ in duress and created new locations for liturgical ritual practices. (Arafath 2018, 25)

In a similar vein, Aram Kuzhiyan Muneer (2015, 13) states: “As the tradition goes, Shaikh Zainuddin composed this mawlud when approached by people from Ponnani and its neighbourhoods who were fearful of deadly disease breaking out in their midst.” But why would Zaynaddīn I compose a mawlid, a text celebrating the prophet’s birth, on such an occasion? We find a possible explanation for this when we look at the overall development of mawlid practices two hundred years after the first mawlid texts emerged. As Katz (2007, 2019) has shown, by the late fifteenth century a mawlid reading was no longer limited to the commemoration of the prophet’s birth in the month Rabīʿ al-awwal but had been extended to other occasions that would call for God’s blessings and support. Mawlid readings were regarded as meritorious acts and expressed joy and gratefulness. Moreover, by the very nature of their content and text practices, mawlid readings included the performance of praise and the invocation of blessings for the prophet, two acts generally believed as earning the prophet’s support in return. This support is conceptualised as the prophet’s intercession (shafāʿa) with God for a supplication.41 By the time when Manqūṣ Mawlid was composed, then, the primary function of its reading may well have been one of rogation and supplication. From this perspective, the mawlid reading did not simply serve to strengthen the faith and identity of the Muslim community by recollecting the prophet’s birth and his message; rather, by praising his perfect virtues and invoking God’s blessings upon him, a mawlid reading offered the communal and active retrieval of Muḥammad’s support and succour through performance.

Two further potential indications for such a function should be mentioned here. These pertain to the concluding prayer and to the Quranic verse that is chosen for citation. With only contemporary prints available at hand, we have no way to tell from what period the concluding prayer (duʿāʾ) stems, and any definitive conclusion will need a thorough examination of the textual history of Manqūṣ Mawlid. Yet, it is tempting to note that the prayer contains some terms which hint to a context that Arafath and Muneer describe. It starts in a general and unspecific manner, addressing topics that are included in many prayers of this type, such as the plea for healing, forgiveness, and salvation. But then, in addition to the general supplications, the prayer tantalisingly mentions “ahl baladinā” (people of our homeland) and “ṭāʿūn” (plague) next to “wabāʾ qāṭiʿ” (drastic epidemic) (63 Waka mawlid kitab, n.d., 39).

Both ṭāʿūn and wabāʾ are terms for epidemic or mass disease. In the Arab lands of the Eastern Mediterranean, ṭāʿūn became primarily associated with the plague or Black Death. The Black Death was a painfully familiar phenomenon for the region, and therefore a subject for Muslim scholars early on. The Cairo-based scholar and litterateur Ibn Abī Ḥajala (d. 1375) composed his treatise Dafʿ an-niqma bi-ṣ-ṣalāt ʿalā nabī ar-raḥma (Fighting the Adversities Through the Invocation of Blessings for the Prophet) on the occasion of the plague outbreak in 1362–64 and lists no less than 33 plague outbreaks from the pre-Islamic era to his lifetime. He gives a remarkably precise definition of both terms: Ibn Abī Ḥajala defines ṭāʿūn as a specific mass disease and describes its plague-specific symptoms in detail. In contrast, he defines wabāʾ as an unspecific mass disease with the typical characteristics of an epidemic: the disease occurs in one region of the earth, is different from other diseases by its high degree of spreading and shows typical symptoms that may vary from one historic case to the next (Herdt 2017, 222). Thus, it is not unlikely that ṭāʿūn and wabāʾ refer to a new epidemic disease in sixteenth-century Malabar.

Furthermore, the supplication is articulated for the sake of ahl baladinā. This phrasing, referring to the inhabitants of a specific region, is rather uncommon in the concluding supplications of other mawlid texts. More common is the supplication for those who are present during the reading (al-ḥāḍirūn) and/or for all Muslims in general (al-muslimūn) instead of those living in a specific region.

Finally, the Manqūṣ Mawlid chose to quote but one verse from the Quran: “To you has come a messenger, from among yourselves, aggrieved by the hardship you suffer, concerned for you, kind and compassionate towards the believers (Q 9: 128).” The quote is inserted between the introduction and the first narrated episode (on the light) and thereby serves as a motto for the text. Keeping lacking evidence in the form of manuscripts in mind, one cannot help noticing that this quote resonates with the duʿāʾ and the adversaries the Muslim community was facing in early sixteenth-century Malabar. Such an extra-ordinary situation may explain why it was deemed necessary to compose a separate, local mawlid text instead of using the already existing ones.

Moreover, mawlid as a religious practice is not limited to the roles of a speaker and his audience but builds heavily on the interaction between performers and listeners and has a strong inclusive appeal. The communal performance of invocations and refrains works as a community-building tool and provides a new access to and experience of Arabic. The mawlid finds its audience—and participants—in the increasing number of immigrants and students in Ponnani and marks a new stage in the development of Muslim communities and the role of Arabic.

In parallel to the growing familiarity with the Arabic script through the educational institutions in Ponnani as described by Kooriadathodi (2016) and Arafath (2018, 2020), the mawlid genre can be regarded as a step in that process of reaching out for a broader Muslim Malabar audience, beyond the scholarly elite trained in Arabic. It might even have had an impact on establishing a vernacular Muslim language capable of addressing an even wider audience, culminating in a new poetic genre, namely the māla written in Arabic Malayalam, whose performance shows similar functions to the performance of mawlid (see Gamliel 2017 for occasions of māla performances). The first traceable example of Arabic Malayalam is the already mentioned Muḥyīddīn Māla, a lengthy poem praising the eponym of the Qādirīya order ʿAbdalqādir al-Jīlānī composed by Qāḍī Muḥammad in 1607. This composition is characterised by joining two literary traditions beautifully referred to in a meta-poetic statement by the composer as “pearl” and “ruby”. In verse 142, al-Qāḍī Muḥammad designates his poetic work as a garland he created by “weaving pearls and rubies together,” or a work he has “strung by joining together pearl and ruby” (63 Waka mawlid kitab, n.d., 173; translations in Arafath 2020, 13; Gamliel 2017, 28). Gamliel takes this image as analogy to an earlier genre in Malayalam literature in “a language hybrid known as Maṇipravāḷam, ‘rubies and corals’,” an amalgamation of Malayalam and Sanskrit (Gamliel 2017, 25–26), and highlights the effect of contrasting colours in the new pair as opposed to the colour harmony of rubies and corals. Arafath interprets the pearl as referring to the Arabic script and the ruby referring to Malayalam language:

Qadi Muhammed seems to have deployed the allegory of ‘pearl’ (an expensive oceanic commodity) to designate the Arabic script that was the form of the Muhiyuddinmala, while using ‘ruby’ (an expensive terrestrial object) to denote polyglossic spoken Malayalam that formed the matter of the text. (Arafath 2020, 13–14)

I take ‘pearl’, furthermore, more concretely as referring to the Arabic poetic tradition. The imagery of the pearl evokes a metaphorical description of poetry which is deeply rooted in the Arabic literary culture. Arab philologists have likened poetry and prose to pearls that are either stringed or dispersed (naẓm / nathr). Stringed pearls allegorically describe the well-ordered words of poetry that are structured by rhyme and metre. As we have seen, Arabic poetry is marked by an end-rhyme. This feature indeed forms a contrast to the Dravidian tradition of first-phoneme rhymes, here represented by rubies. Yet the Muḥyīddīn Māla features both, first-phoneme and end-rhymes, thus stringing pearls and rubies together. And it might not be without significance that the poetic device of the end-rhyme must have been familiar to many Malabar Muslims through listening to mawlid recitations, through both sajʿ passages and qaṣīda.

Multiple-Text Compilations: The Material Context of Performative Texts

Let me end with a short example that shows the entanglement of technical terms, practices, and material objects rooted in manuscript cultures. Muneer mentions a special term applied to compilations that contain mawlid and other devotional texts, called sabeena or safeena.

Both Manqus and Sharraf al-Anam, like other mawluds and devotional songs, circulate in prayer manuals/pamphlets which are synecdochically called mawlud kitab (book of mawlud) or edu (literally “leaf” or “page” of a book)—more interestingly, these prayer manuals are also known as sabeenas/safeenas, a word which I learnt from my mother at a very early age and then kept hearing often as I grew up in a village in South Malabar. The word “sabeena” is a corruption of the Persian “shabeena” which means “nocturnal.” Since Mappilas used to (and continue to) recite mawluds, malas, and other devotional songs, and a variety of litanies from the prayer book daily at night, most especially between maghrib (sunset prayer) and ‘isha’ (night prayer), the prayer book was also called sabeena/safeena metonymically, meaning “that which is recited at night.” (Muneer 2015, 13–14)

Though Muneer favours the Persian etymology, there is plausibility for an Arabic etymology as well. I would like to offer, at this point, meanings and uses of safeena (Arab. safīna) from the Arabo-Islamic book culture. In North Africa, Egypt, and the Eastern Levant, safīna (lit. ship, vessel) is the name for collections of strophic poetry, mainly muwashshaḥāt.42 The term safīna often features in the title where it is either combined with an author’s name or woven into a typical ornate rhyming title. Dwight Reynolds (2012, 76) names safīna as one of the terms for the ‘songbook’ genre that was “well-established and widespread from Morocco to Syria to Yemen from at least the 16th century.” He further gives an interesting observation about Yemen, where safīna was used for collections of the Yemeni local strophic poetry (ḥumaynī). More commonly, however, it was used as a scrapbook or notebook of different types of texts. It belonged to individuals who either copied single texts from books or wrote them down as they heard them performed (Reynolds 2012, 75–76, with further references for Yemen).

Moreover, there is a special binding technique connected to that term. In the Islamicate manuscript culture, safīna designates a format in which the single pages are sewed together at the smaller side of the paper. It is held vertically when used, the sewing being at the top. This oblong format was used as a scrapbook, since it was typically light enough to be carried around, and it was also sold with empty pages on the book market (Scheper 2015, 260, 313). Reynolds (2012, 75) remarks he has never encountered a muwashshaḥ collection in that format; however, the Berlin State Library hosts some manuscripts of strophic poetry in that format (average size 13×21 cm).43 Taking safeena as an Arabic term, such a heritage from the Islamicate manuscript culture may alternatively explain why compilations that contain mawlid, prayers, and devotional poetry in Kerala are called this. The Arabic meaning of safīna allows two interpretations of the term that connect to the manuscript culture: safīna as a ship, evoked by the horizontal shape, or safīna as a vessel that gets gradually filled by the scribe. It is probable that safīna remained the term for collections—of performative texts written down over the course of time—even after their material shape was no longer connected to the specific binding technique; and the term continued to be used for printed volumes. Many mawlid compilations still possess a portable character since they are not heavy hardcover prints but have the size and weight of booklets.

Finally, Regula Burckhardt Qureshi mentions a use of the term safīna among Pakistani Muslims which seems to be based on the definition of safīna as a compilation of devotional poetry, maybe even in the form of a scrapbook collection. In her study on the Hindustani music tradition connected to the Sufi practice (qawwālī), she examines the status of written sources. Despite the existence of written compilations of Persian poetry and of individual poets’ works, she states, music performers as well as individual Sufis usually

[…] use such sources only as a reference or backup to their memory, and it is in this sense that they identify poetry and music as two contrasting domains of knowledge: ʿilm-e-safīnā (knowledge of the written page) and ʿilm-e-sīnā (the knowledge of the memory). (Qureshi 1991, 107)

The term safīna, spreading across regions and languages, yet retains a semantic aspect that is shared in all described contexts: it denotes a collection of various texts, often compiled by an individual person from different sources; the criteria for selection are based on what one sees as worth obtaining, be it useful or beautiful; the texts are not necessarily religious but definitely belong to performative genres such as poetry, prayers, and mawlid.

Conclusion

Mawlid as a text for communal liturgical reading emerged in different cultural and historical settings and formed an important part of the literary networks between the Arab lands and the Malabar Coast. In my analysis of an early Arabic mawlid text from Malabar, Manqūṣ Mawlid, I have differentiated between traveling texts and traveling genres. Sharaf al-anām constitutes an example of a traveling text. In its function as a model for Manqūṣ Mawlid, however, the objective was not the imitation of a text but the appropriation of its form and thereby conceptualising a mawlid text as a genre. Furthermore, the investigation of practices that are related to mawlid texts is crucial for their contextualisation. In case of Manqūṣ Mawlid, it is demonstrative of the rise of Ponnani as a Muslim intellectual centre and points to an intensified role of the Arabic language (and script) in the Muslim community and ritual life beyond the core rituals of ritual prayer, or ṣalāt, and the canonical sermon, or khuṭba.

Texts like Sharaf al-anām moved across regions and were widely used in the Arab world and beyond, as manuscripts and compilations of devotional texts indicate. In the case of Manqūṣ Mawlid, one of the earliest Arabic mawlid texts from the Malabar Coast and ascribed to Zaynaddīn I (d. 1522), evidence from two different angles suggest that texts like Sharaf al-anām have served as a model for its composition. The first cluster of evidence comes from historical sources like historiographic writing and biographical dictionaries. These sources identify historical figures embedded in the scholarly networks between Cairo, the Hijaz, South Arabia, Gujarat, and the Malabar Coast. Ibn ad-Daybaʿ from Zabīd reports of mawlid readings in his hometown in the late fifteenth century. His father had migrated to India; and Ibn ad-Daybaʿ travelled to the Hijaz where he spent a longer sojourn to study. Ibn ad-Daybaʿ furthermore claimed to have identified the author of Sharaf al-anām, which is a strong indicator that the text was known in Yemen. ʿAbdalqādir al-ʿAydarūs, writing from Gujarat, not only includes this incident in his entry on Ibn ad-Daybaʿ’s biography; he furthermore adds the remark that he heard many people ascribing the text to Ibn al-Jawzī instead. This shows that the text circulated in Gujarat as well. The presumed author of Manqūṣ Mawlid, Zaynaddīn I, would have become acquainted with the mawlid genre at the latest during his travel to the Hijaz and Cairo; yet it is not unlikely that it happened even before that in Malabar. Certainly, Arabic praise poetry for the prophet circulated among Malabar scholars, as the poetic emulations demonstrate.

The second cluster of evidence comes from the analysis of form and style. The author of Manqūṣ Mawlid applies the technique of compiling different source material on the prophet’s birth and early life into a form that, by length and stylistic features, is suited for liturgical reading during a single gathering. Auditory features of rhythm and rhyme show in the long passages in sajʿ and in qaṣīda poetry. Overlapping in terms of content, as in episodes on the wandering light or in the qaṣīda, which follows the account of Muhammad’s birth, point to Sharaf al-anām as a model as well but should not be overestimated, since these feature in a number of similar mawlid texts like Mawlid al-ʿArūs. Rather, the fact that episodes from Sharaf al-anām are missing in Manqūṣ Mawlid shows that Sharaf al-anām was taken primarily as a genre model, whereas full congruence in terms of content was not the intention.

Manqūṣ Mawlid is traditionally linked to the wars and other adversaries following the Portuguese occupation of parts of Malabar and to the city of Ponnani, where Muslims from Kochi in the South and from Calicut in the North sought refuge.44 Textual evidence in the Quranic quote and the concluding prayer—provided that the prayer is not a later addition—support this timing. The composition of a performative mawlid text in times of crises blends well into the overall development of mawlid practices. By the late fifteenth century, a mawlid reading was no longer limited to the birth anniversary of the prophet but was performed on other occasions as well. A mawlid reading was deemed a meritorious deed and formed a supererogatory act of piety to which listeners could actively contribute, at least by performing the invocations of blessing. A mawlid reading was thus appropriate to secure the prophet’s intercession for a supplication to God.

Manqūṣ Mawlid most probably did not address an audience that was completely unfamiliar with the mawlid genre. Mawlid may have been known in Malabar either through returnees from the Hijaz, through Muslim traders between Southeast Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, or through immigrants from Yemen, where mawlid was firmly established by the lifetime of Zaynaddīn I. Surely, to include the circulation of manuscripts is a desideratum because it would add further evidence. However, such an examination deserves a study of its own, not least due to the fact that a large part of manuscripts in Malabar is not publicly available but remains in private collections (Kooria 2018, xvi). In the case of mawlid, moreover, the evidence of manuscripts is not the only indication for the circulation of texts, because mawlid texts function as oral performances. A mawlid text was composed for primarily auditive consumption, and it is in this form that most Muslims would have encountered such a text. It is therefore not purely anecdotal when ʿĀʾisha al-Bāʿūnīya reports that she listened to a mawlid in Mecca.

Mawlid readings, through their aesthetic features and the participation of listeners, offered a new experience of Arabic, both as a language of ritual and a language of poetry. This mirrors the social changes of the Malabar Muslim community, especially in Ponnani, which had become a centre of Muslim learning with a rising number of immigrants, educational institutions, and students. A growing educated group well versed in Arabic was the audience of literary productions like praise poetry for the prophet and mawlid. Hence, to analyse transregional literary networks, combining the evaluation of literary forms, linguistic transfer, and text practices constitutes a promising approach to the investigation of Indian Ocean historiography. From this angle, texts from the field of poetry and liturgy gain significance as sources for studying the development of the Muslim communities in Malabar.

Acknowledgments

This is the expanded version of a presentation given at the international workshop Arabic and Islam on the Move: Cross-cultural Encounters between Arabia and Malabar 900s-1500s, held at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg Dynamics of the History of Religions between Europe and Asia, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, and organised by Ophira Gamliel (23–24 May 2017). I am indebted to the Käte Hamburger Kolleg and Ophira Gamliel for inviting me to the workshop. I thank Alex Cuffel for including my paper in this special issue on The Indian Ocean and its Periphery as well as both anonymous reviewers for their valuable observations and suggestions. Research for this paper is based on my project “Mawlid-texts from the 13th to the 18th century: Prophetic piety as ritual performance?,” funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)—reference number 389265477.

Abbreviations

- GAL

- Brockelmann, Carl. 1902. Geschichte der Arabischen Litteratur, vol. 2, Weimar: Emil Felber.

- GAL S

- Brockelmann, Carl. 1996. Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur. Zweiter Supplementband. Leiden: Brill.

References

63 Waka mawlid kitāb [A Book of 63 mawlid]. n.d. Thirurangady: C. H. Muḥammad and Sons, ʿĀmir al-Islām, Lithopowerpress.

Abū l-Fatḥ, Nawāl. 1995. al-Mutāḥ min al-mawālid wa-l-anāshīd al-milāḥ [The Ordained of mawlid and Praise Poetry]. Damascus: Dār ash-Shādī.

Alatas, Ismail Fajrie. 2014. “ʿAbdallāh b. ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam Three, edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill.

Al Faruqi, Lois (Lamya’). 1995. “Mawlid and mālid: Genres of Islamic Religious Art from the Sultanate of Oman.” In The Complete Documents of the International Symposium on the Traditional Music in Oman: October 6-16, 1985, edited by Issam el-Mallah, 3:17–34. Wilhelmshaven: Noetzel.

al-Qāḍī Abū l-Faḍl ʿIyāḍ al-Yaḥṣubī. n.d. al-Shifā bi-taʿrīf ḥuqūq al-Muṣṭafā [The Healing through Knowing the Muḥammadan Truth]. Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-ʿIlmīya.

Amer, Ayal. 2019. “al-Malībārī, Zayn al-Dīn.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam Three, edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson. Vol. 6. Leiden: Brill.

Arafath, Yasser P. K. 2018. “Malabar Ulema in the Shafiite Cosmopolis: Fitna, Piety and Resistance in the Age of Fasad.” The Medieval History Journal 21: 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971945817750506.

———. 2020. “Polyglossic Malabar: Arabi-Malayalam and the Muhiyuddinmala in the Age of Transition (1600s-1750s).” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 3: 1–23.