The Complexity of Religious Traditions in Quanzhou 泉州 under Mongol Rule: An Inscription from Chunyang 純陽 Cave in Mt. Qingyuan 清源, Quanzhou

This paper discusses the complexity of the religious traditions in Quanzhou (Fujian, China), the largest international trade port under Mongol rule. The contribution of presumed Persian Muslim Pu Shougeng 蒲壽庚to the reconstruction of a Taoist-Buddhist shrine was taken as the case study. The external conditions surrounding his composite religious act (beyond private beliefs) were also observed in terms of individual goals, backgrounds, and social networks. For this purpose, the author presents the Chinese stone inscription from Quanzhou (in Fujian, China) titled “Zhong jian Qingyuan Chunyang dong ji 重建清源純陽洞記 (Record of Reconstruction of the Chunyang Cave in Qingyuan Mountain),” dated to the fourth year of Hou-Zhiyuan 後至元 (1338) during the Yuan period.

Religious Tolerance, Mongol Empire, China, Islam, Taoism, Buddhism, religious inscriptions, Fujian

Introduction

The subject of this paper is the interchange of Islamic, Taoist, and Buddhist religious traditions in Fujian 福建 Province under Mongol rule. In particular, it analyzes the religious activities and social networks of the Pu Shougeng 蒲壽庚, descendants of the Persians of Quanzhou 泉州, based on Chinese inscriptions commemorating the construction of Taoist and Buddhist temples.

The Mongol period (thirteenth to fourteenth centuries) is characterized by the intertwining of a variety of religious traditions. Fujian province, on the southeast coast of mainland China, during the Mongol period is an interesting case in which intense intercourse among various cultural traditions and high degrees of cultural tolerance were present. Actually, the Fujian province of that period is known for historical sources referring to the influence of various foreign religions as well as a range of religious relics, especially from Quanzhou City, including those from Islamic, Manichaean, Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu traditions (see Wu 1957; Clark 2006).1

In Fujian, Manichaeism, which originated in Sasanian Persia and was introduced to China via Central Asia, continues to exert a long-term influence. Previous research on Manichaeism provides an important insight into the coexistence of foreign religions in China. The Manichaean shrine on Huabiao 華表 Hill in Jinjiang 晋江, southwest of Quanzhou, is one testimony to the ‘religious diversity’ under Mongol rule.2 The shrine was called cao’an 草庵 (“a thatched nunnery”) in historical sources, and the statue of Mani as the Buddha of Light on the rear wall of the temple, carved in 1339, has clear Manichaean features, such as the design of segumenta (squares) on both breasts of his robe. This feature was first noted in J. Ebert’s study on Manichaean paintings in Turfan (Ebert 2004). Recently, eight Manichaean silk paintings, including Rokudōzu 六道圖 (six paths painting), produced around Ningbo 寧波 during the Mongol period and imported to Japan (where they are now), have attracted much attention. These Manichaean paintings depict Mani and Christ in the style of Chinese Buddhist paintings, and at first glance, it appears as if Manichaeism was accepted into Chinese society in a way that merged with the local religious culture.3 At the same time, it should be noted that caution is in order in assigning syncretism to the religious pluralism of this era, as Yoshida Yutaka says:

Mani believed that his message should be translated into all the languages of the world. Ideally, the translation should be adapted to the culture of the target language. This aspect gives the impression that Manichaeism is more of a mixed religion than it really is. It is not only natural that the Manichaean Buddhist scriptures translated into Chinese should look like Buddhist scriptures, but also that this was the missionary strategy of Manichaeism. (Yoshida and Furukawa 2015, 26–27)

Inspired by these studies of Manichaean inscriptions and paintings as they relate to the complexity of religion in Mongol-period China, this paper will present another inscription from Fujian in the same period. This inscription commemorates the construction of a Taoist-Buddhist shrine in Chunyang 純陽 cave in Qingyuan 清源 Mountain, Quanzhou, by the Pu Shougeng and his elder brother, who are believed to be descendants of Persians. This paper focuses on the external factors behind the construction of the temple, such as the diplomatic mission of Pu and the social network of the Pu brothers, and analyzes the structure of religious coexistence in Quanzhou.

The following chapters first review the influx of Persian speakers and the introduction of Islam into Fujian before and during the Mongol rule. Then, the contribution reviews the religious traditions in the Fujian region under Mongol rule, paying special attention to their openness or seclusion, adding some data based on the studies in recent years. To conclude, the author proposes a hypothesis on the structure of religious coexistence related to the periodical fluctuation of the influx of Persian speakers in Fujian. Finally, we will focus on the case of the Chinese inscription in Chunyang cave on Qingyuan Mountain during the Mongol-Yuan 元 period.

The fact that Pu Shougeng undertook the construction of a Taoist-Buddhist temple with his elder brother is not necessarily a clue about their faith on its own. Although it is impossible to know the exact beliefs of Pu Shougeng himself, it is likely that the Persians of this period were basically Muslims, and there are several indications of the Pu family in Quanzhou practicing the Islamic tradition. For example, zhenwu 鎮撫 (judge, a junior officer in the Ming troops) Pu Heli 蒲和日, considered the Pu lineage of Quanzhou, erected a stone monument near the tomb of a Muslim saint in the Linshan 霊山 Islamic Cemetery in an eastern suburb of Quanzhou, which commemorated Muslim admiral Zheng He’s 鄭和 visit. He had burned incense here in 1417 on his way to the “Western Ocean” (Kawagoe 1977; Lin [1988] 2004, 162–63).

Historical Background of the Persian Immigrants to Fujian in China

The influx of Persians as well as other foreign populations to the coastal region of China, including Fujian province, was closely related to the long-distance trade and political situation both on the Central Eurasian landmass and in the Southern Maritime region.4 This article categorizes Islamic immigrants including Persians into the following four types according to historical background and cultural features.

- Category (a): Old immigrants via sea routes: Persian sea traders during the Song 宋 period

- Category (b): Localized Persian immigrants: Pu 蒲 family from the Southern Song to the Yuan period

- Category (c): Newcomers via inland routes: Muslim elites from Central Asia and Iran during the Yuan period

- Category (d): Newcomers via sea routes: Muslim merchants and various migrants during the Yuan period.

In the following sections, the background history of each migration category will be discussed.

(a) Influx of Persian Speakers from Seaborne Trade Routes

By the Tang 唐 period (618–907), important port cities such as Guangzhou 廣州 and Yangzhou 揚州 prospered and played major roles as commercial centers. A wide array of migrants, including Persians, were present in Guangzhou and Yangzhou.

Middle Eastern merchants were already traveling to East Asia by the first century (Wade 2010, 181). Antonino Forte pointed to the period between 148 and 845 as the period of greatest Iranian influence in China (1999). However, Iranians in the Tang Dynasty were more closely associated with Buddhism, Christianity, Manichaeism, and Zoroastrianism than Islam. Meanwhile, Ralph Kauz, citing an article by Rafael Israeli, emphasized the beginnings of Muslim immigration, which came mainly to southern China, and wrote that since the seventh century, Muslims have made up the majority immigrant group to China. These Muslim immigrants, mainly Arabs and Persians, first came to China by sea (Fan Ke 2001, 309–10; Israeli 2000).

In the ninth and tenth centuries, the Persian origin of the Liu 劉 clan of the Southern Han (Nan Han 南漢) in Guangdong 廣東 was noted, and the tombs of the Min 閩 Kingdoms of Southern Han and Fujian Persian pottery were excavated. Liu is considered a transliteration of ᶜAlī, also translated as Li 李 (Schottenhammer 2015, 3–4). “The 10th–12th centuries were to see quite intense interaction between the ports along the Maritime Silk Road, including those of Southeast Asia, and Chinese entrepôts along the coast of southern China” (Wade 2010, 181). During the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1276), the status of the most important port city on the coast of southern China shifted from Guangzhou and Yangzhou to Quanzhou in southern Fujian and continued until 1368, that is, the end of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (Fan Ke 2001, 312–14).

Since the early Northern Song (960–1127) period, sea traders surnamed Li and Pu were especially prominent in Chinese documents.5 Recently, Geoff Wade suggested that these “surnames” may refer to a specific group of Muslims, such as the Shi’ites (2010). In any case, it probably refers to the Persian-speaking people who made up the majority of Muslims traveling to and from the Indian Ocean at the time. They form category (a) for the purposes of this paper.

A large portion of the influx of Persian speakers to the Fujian area started during the Southern Song period, which consisted of seaborne trade route travelers. They started to settle in Quanzhou during the late Southern Song period and will form category (b) in the following section. The tide of incoming foreigners continued through the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, which will form category (d).

(b) Localized Persian Immigrants

During the Southern Song period, the immigrant population became settled and localized and they will form the second category, category (b). However, it would be simplistic to interpret them as having been completely sinicized. As an example of the category, we can discuss a figure of the late Southern Song, Pu Shougeng who controlled maritime trade at Quanzhou port in Fujian.

The author supports precedent studies to regard Pu Shougeng as a descendant of Persian merchants because Persian features in Islamic tombstones from Quanzhou suggest that a large part of the immigrants were Persians (Maejima 1952). Added to this, the contemporary epigraphic text of the early Yuan period written by Wang Pan 王磐 reports that Pu Shougeng was a merchant traveling along sea routes for business and was originally a Xiyu ren 西域人 (“people from the west”). Another epigraphic text by Wang Pan tells that Pu Shougeng was originally a Huihe ren 回紇人.6 Huihe originally meant Uighur, Turkish-speaking people from Turfan and other places in Central Asia. However, it also meant ‘Muslim’ during the Yuan period.7 Accordingly, the author infers that the Pu family, at least in Quanzhou, was most likely Muslim of Persian origin.8 Pu Shougeng gained economic and political influence at Quanzhou through his fleet and manpower for maritime trade from the late Southern Song to the early Yuan period. He was granted the title of zhaofushi 招撫使 (commander of the local militia) and shibo tiju 市舶提擧 (the head of shibosi 市舶司, maritime trade supervisorate) during the last years of the Southern Song period. Recent studies in China attested that Pu Shougeng actually bore the title zhigan 制幹, which is a substitute for yuanhai zhizhi shi 沿海制置使, the commander of the Southern Song’s Navy in the coastal provinces. Soon after his surrender to the Yuan, Pu Shougeng was appointed to be canzhi zhengshi 參知政事 (Assistant Administrator) of the Mobile Secretariat at Jiangxi 江西 in 1277 (remote appointment) and finally promoted to pingzhang zhengshi 平章政事 (governor) of the Mobile Secretariat (xingsheng 行省) at Quanzhou (see Liu 2015; Song [1369] 1978, Ch. 9:191, Ch. 10:204; Wu 1988).[^9]

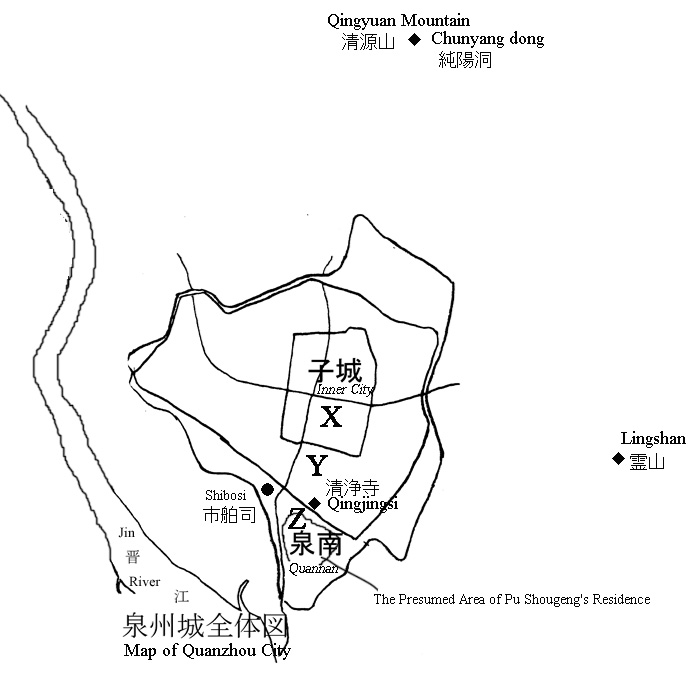

The Pu family’s local influence seems to have lasted until the Yuan period. The old street names in Quanzhou City, which are still preserved today, are said to be related to the lost residence of Pu Shougeng, as is shown in figure 1. The fact that the Pu Shougeng’s residence was adjacent to the mosque Qingjingsi 清淨寺 (“pure and clean” temple) and occupied a large part of the foreigner’s settlement strongly suggests that taken together, the Pu family and Pu Shougeng himself were Persian Muslims.

(c) Newcomers Via Inland Routes: Muslim Elites from Central Asia and Iran

During the Yuan period, the population of the South China coastal region added what I categorize as (c): Newcomers via inland routes: Persian (and Turkish) elites from Central Asia and Iran. The strategy of the Mongol empire to rule Chinese society was behind the influx of category (c).

Soon after the Mongols conquered the Jin 金 dynasty (1115–1234), they had to build a governance and tax collecting system in Zhongyuan 中原 (the Central Plain of China). Since the size of the Mongol ruling class was too small compared to the huge population of subordinate Han 漢 Chinese, they mobilized every possible human resource in their realm and fully utilized their knowledge for the governance of agrarian society and their skill of financial management. Among them, there was a considerable number of Muslim elites from Central Asia and Iran. Their ancestors had surrendered to (and cooperated with) the Mongols during the war against the Qara Khitai Khanate and the Khwārazm Empire and they financially supported the Mongols and immigrated to China under Mongol rule (Rossabi 1981). Families from category (c) were incorporated into the Mongol ruling class through the recruiting system and continued to produce officials in Yuan China. These facts can be confirmed by Chinese and Persian historical sources and by the list of the names of Yuan officials in the Local Gazetteers of Zhenjiang 鎭江, Jinling 金陵 (present-day Nanjing) and the Fujian region (Yang 2003, 163–287; Mukai 2009).

(d) Newcomers via Seaborne Trade Routes

During the Yuan period, Quanzhou continued to be the most important port and prospered from maritime trade. Thus, there were maritime traders, ᶜUlamāᵓs (Arab “scholar”), and religious persons including Sūfīs who migrated to Quanzhou via sea routes. They form category (d) of this paper. As seen below, the Islamic institutions for Muslims were developed based on the contribution of this newcomer Muslim elite cluster via sea routes.

According to the itinerary of a Muslim traveler from Morocco, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa (1304–1369), Quanzhou as well as other cities in China reserved an area for Muslims (which should be Quannan, though it was not perfectly exclusive for Muslims), who had their own religious leader, called Shaikh al-Islām, and an Islamic judge for the Muslims, called qāḍī. During his stay at Quanzhou around 1345, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa received visits from the qāḍī, Tāj al-Dīn of Ardabīl, Shaikh al-Islām Kamāl al-Dīn Abdullāh of Iṣfahān, and merchants Sharaf al-Dīn of Tabrīz, all of whom seemingly came from the cities in Iran (Ibn Baṭṭūṭa 1994, 4:894–95).

Ibn Baṭṭūṭa also mentioned an eminent Shaikh at Quanzhou, Burhān al-Dīn al-Kāzerūnī (of Kāzerūn), who was a representative of a Sūfī order, Kāzerūniyya established at Kāzerūn in Iran. He had a hānäqāh (hospice) outside the town to whom the merchants make the oblations made to the originator of the Sūfī order, Shaikh al-Isḥāq Ibrāhīm b. Shahtiyār al-Kāzerūnī (963–1033). According to Ralph Kauz, with Wittek’s addition to Köprülüzāde’s article, “the nisba al-Kāzerūnī means not only a person from or with relations to the said city but rather an adherent of the Sūfī order.” Kauz also says that the Kāzerūniyya extended a network of ḥānäqāhs in Anatolia, Iran, and the cities along the shores of the Indian Ocean such as Calicut and Quilon and never lost contact with their motherhouse in Kāzerūn (Kauz 2010, 61, 67). They give the meeting and living places of dervishes and offered accommodation and food for three days free of charge. The ḥānäqāh in Quanzhou was established after Burhān al-Dīn moved to Quanzhou on the tributary ship to the Yuan court during the Huangqing 皇慶 years (1312–1314) (Ibn Baṭṭūṭa 1994, 4:895; Huai et al. [1763] 2000, Ch. 75: 39v–40r).10 The introduction of the ḥānäqāh would have involved the increase in the Muslim immigrant population of Quanzhou through the mid–fourteenth century, as discussed below.

Investigating the Reality of the Entanglement of Religions in Fujian

Periodical Changes in the Muslim Community in Fujian during the Yuan Period

As seen in the former section, in Fujian during the Yuan period, both Chinese and Arabic historical sources testify to the existence of a Muslim population. Persian speakers made up a significant portion of the various types of migrants to the region corresponding to categories (a) to (d). However, there was not enough mapping and data about the spread of Islam in each region of China and about the number and periodical distribution of the migrants during this period. Accordingly, the author tried to gather some data.

Firstly, the author considered the sites of old mosques in China which, according to local tradition, originated during the Mongol period. The following map (figure 1) was created by the author based on the complete list of mosques in China by Wu Jianwei 呉建偉 (1995). We can see that the southeast coast, including Fujian, was one of the places of intensive Muslim population since early times.

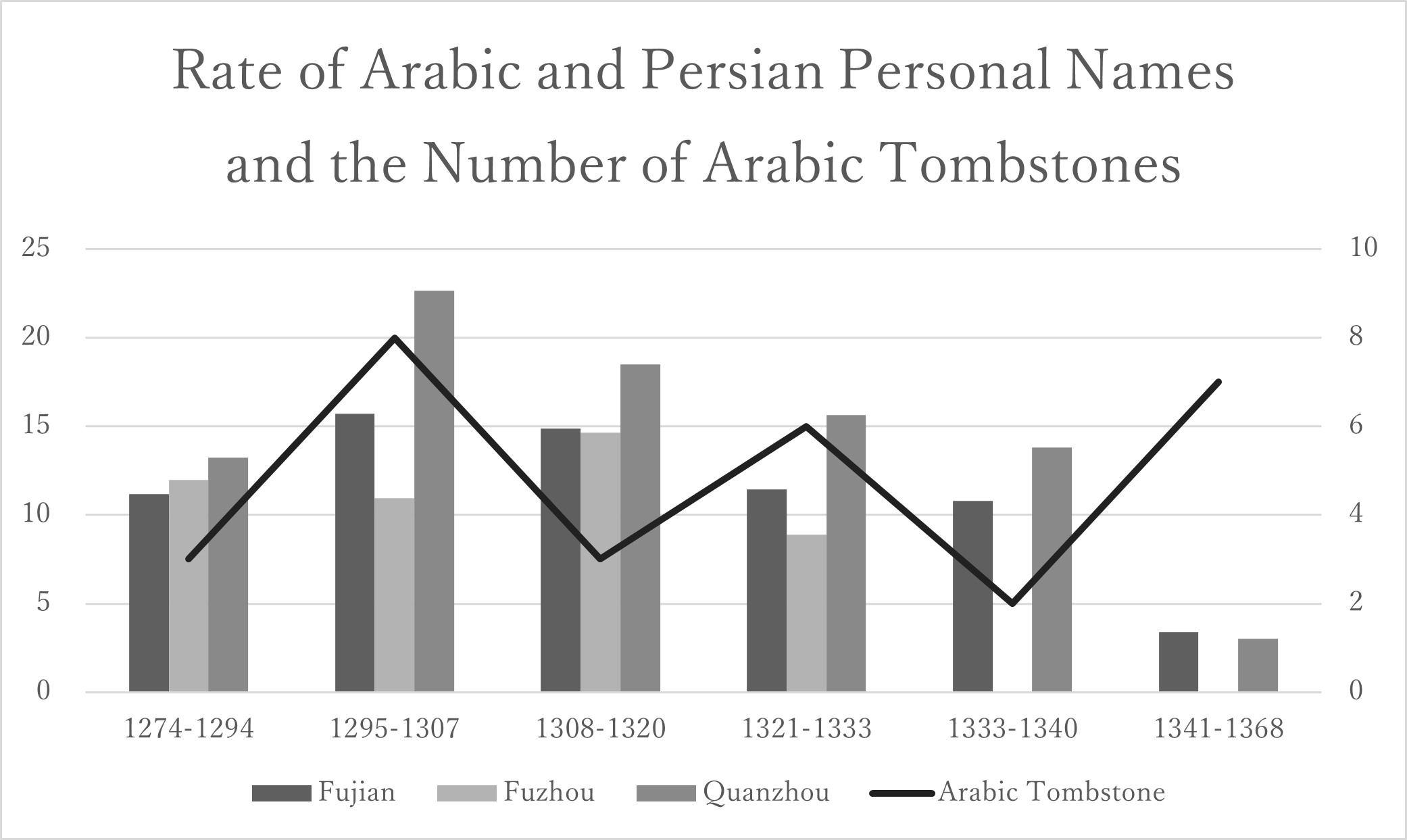

Secondly, the prevalence of Muslim officials in Fujian province seems to have been higher than in other provinces, though there was a decreasing tendency toward the end of the Mongol period (Mukai 2010, 440, 2009, 83–84). Figure 2 shows the fluctuation of the number of officials with Islamic names (histogram).11 Although not all these officials with Islamic names were necessarily Muslims, it shows that a significant number of Islamic officials had been appointed in Fujian province.

Simultaneously, maritime merchants and the descendants of Persians from overseas were part of a local, hereditary elite stratum. Arabic tombstones with some Persian and Turkish elements were excavated in the Fujian region, namely in Quanzhou, showing that the Yuan period was the peak of an influx of the Muslim population. Many entombed people are considered to have been Persian and Turkish speakers who were from an elite cluster in the Khwārazm empire. However, as mentioned in the former section, there were also some maritime traders, ᶜUlamāᵓs, and Sūfīs who had migrated to China via sea routes, category (d). The periodical distribution of the Arabic tombstones is shown in figure 2 (line graph) (see also Mukai 2002, 98). There were several fluctuations in the number of tombstones.

To conclude, seen from the three different kinds of spatial and periodical data on the spread of Islam and migrants in and into China, there was a long-term tendency of an influx of Persian speakers into Fujian, which corresponds to this article’s categories (c) and (d). Certainly, there were still examples from category (b) during this period.12 Meanwhile, the process of the influx of Persian speakers into Fujian province during the Song and Yuan periods was not a simple, linear process; there were both short and long-term fluctuations from time to time. The fluctuation of the migration into the region, not only between the two dynastic periods but also between the reign of each of the emperors of the Yuan period, brought different patterns or different degrees of assimilation, which lead to functional differentiation among foreigners.

Geographical Analyses of the Entanglement of Religions in Quanzhou

During the Song and Yuan period, the quarter for foreigners in the southern quarter of Quanzhou, called Quannan (see figure 1), was where the foreign visitors and a part of the settled foreigners of categories (b) and (d) lived. Nevertheless, the intermingling of Chinese and foreigners was not forbidden.13 For example, a Local Gazetteer, Qianlong Quanzhou fuzhi 乾隆泉州府志 (edited in 1763), reveals that the aforementioned Shaikh at Quanzhou, Burhān al-Dīn, resided along the Shop Street (paipu jie 排舗街) in the quarter for foreigners called Quannan (Huai [1763] 2000, Ch. 75, 39v–40r.).

The mosque Qingjingsi was built in 1131 (or in 1009–1010) on the border of the quarter for foreigners (Z in figure 1) and the main block of the city (Y including X in figure 1); in other words, it was at the place of contact between the Muslims and Chinese. This explains why the Chinese stone stele, Chongli Qingjingsi bei ji 重立清浄寺碑記 (Stone Record of the Reconstruction of the Clear and Pure Temple), was composed by Wu Jian 呉鑑 in 1350 to commemorate the restoration of the mosque in the late Yuan period and was installed in that mosque.14 Wu introduces Islam, their country, and the culture of Muslims in a favorable tone, and it seems to have been written for Han Chinese to explain how Islam and Muslim people lived together harmoniously in Quanzhou.

To sum up, in Quanzhou city during the Mongol period, cross-cultural contact between Muslims and other peoples was not avoided. Rather, from the viewpoint of institutional and geographical settings, there were ample opportunities for contact between them. Actually, the old Muslim representative of category (b), the Pu family, had a connection with the Han Chinese local elite cluster, which is mentioned in previous studies (So 1991, 20–21, 2000, 108–10). As is shown on the map (figure 1), based on local tradition, Pu Shougeng’s residence occupied a large part of the foreigners’ quarter in Quannan and was also adjacent to the central part of the city where many Han Chinese lived (Mukai 2007, 96). It is clear from these geographical settings that his family definitely occupied a representative position among foreigners in Quanzhou and could have played a role as a mediator between foreigners and Han Chinese.

Furthermore, during the Yuan period, the government was served by many semuren 色目人 (“various kinds of people,” mainly Non-Han Chinese), and in Quanzhou Muslims were predominant among semuren.15 Officials, including Mongols, semuren, or the people of category (c), generally worked in the center of the city (X in figure 1). Accordingly, the people in categories (b) and (c) had some channels to link the host society with the Muslim community, including category (a) newcomers, who were not isolated islands in Quanzhou city.

The author believes that the people in category (b) were in a situation where their religious traditions were compromised as a result of long-term cultural contacts. Meanwhile, categories (c) and (d) immigrants had solid relations with their religious traditions. In the following section of this article, the relationship between the different levels of assimilation and the culture of tolerance will be analyzed.

Solid Religious Tradition: Islamic Inscriptions from China’s Coastal Region

Arabic Tombstones of “Exile Martyr” from Lingshan

It should be noted that the first example of the word “exile martyr” can be found on the tombstone of Muḥammad Shāh b. Khwārazm Shāh (Khwārazm Shāh’s son, Muḥammad Shāh), excavated at the old Muslim cemetery in the Linshan Islamic Cemetery in the Eastern suburb of Quanzhou, where the legendary Islamic evangelists were buried and worshiped (Chen 1991, 193–94, no. 114). It is said to be the word of the prophet Muḥammad. Two variants, “He who dies an exile dies a martyr,” as well as its shortened form, “The death of the exile is martyrdom,” are frequently seen in the Arabic inscriptions on graves found in Quanzhou. And Arabic tombstones excavated near China’s coastal region provide data as to the place of origin of the deceased and their date of death (primarily during the Yuan period), which tells us that a significant part of immigrants came from the former Khwārazm Empire in China’s coastal region. These facts suggest that immigrants from the former Khwārazm Empire preserved a ‘solid identity’ as foreign Muslims. Additionally, the exclusive usage of the Arabic language on their tombstones connects their identity to their homeland’s Islamic tradition.

Chinese Inscription of the Old Mosque Qingjingsi in Quanzhou

Another example can be observed in a Chinese inscription preserved in an old mosque (Qingjingsi) in Quanzhou. The stone stele was erected in 1345 to commemorate the restoration of the mosque and a member of the local elite, Wu Jian, wrote the monumental inscription for it. The inscription recorded the history of Muslim immigrants in Quanzhou, with a detailed introduction of Islam and its culture:

For more than 800 years until now, the Arabs have strictly adhered to this faith. Though living in a foreign country, they passed it on to their children and grandchildren, extending through the generations they did not dare to change it. … I have heard the following words of the elders: when Arabia (T’ieh-chih-shih 帖直氏) first entered into the official picture, its local customs and doctrines were quite different from other countries. On the basis of the Western Envoys and Records of the Barbarian Islands and such records, I attach more belief to those words. On that basis, it is said: ‘It is Heaven’s wish to give equal shares to the entire world,’ but it has not become so in just one day. (Vermeer 1991, 124)

In my opinion, the Muslim population experienced fluctuations throughout the Mongol period. Some of the Muslim population assimilated into Chinese culture after the decline in the number of Muslim newcomers. However, according to this stone inscription, Muslims in Quanzhou adhered to the Islamic tradition and preserved their own culture until as late as the 1350s in the late Yuan period.

Complex Religious Tradition: A Taoist Shrine and Pu Shougeng

Fujian province had a long tradition of coexistence with foreign religions from overseas. This point also concerns the cosmopolitan nature of the port cities that were open to the outside world. This cosmopolitan culture also reflects an important feature of maritime trade, that is, it was not conducted based on a single cultural tradition or a single religion but by various coexisting groups and cultural traditions, and together they supported the prosperity of the entire trade network. A Chinese stone inscription relating to the ‘localized’ Persian merchant Pu Shougeng from the late Southern Song to the early Yuan period refers to this complex situation.

In 1274, after Yuan troops captured the capital and occupied the coastal region of Southern Song, Chinese port cities opened to overseas countries. Khubilai dispatched sea traders to overseas countries to establish trade relations with them (later, envoys were sent to other countries under the direct initiative of the Yuan court). As Pu Shougeng had controlled the “ships of foreign trade” (fanbo 番舶) at Quanzhou in the late Southern Song period, many former subordinates of Pu Shougeng were dispatched to overseas countries. At times, a Pu and Mongolian colleague, Suodu 唆都, would dispatch trade ships without the permission of the Yuan court. Apparently, Pu Shougeng was motivated by the profits he earned through extending his own trade relations and he exploited the overseas missions to this end. A Chinese stone inscription, located at the Taoist site of the “pure and sunny” cave (Chunyang dong純陽洞) on the “clean source” mountain (Qingyuan shan 清源山), tells us that Pu Shougeng and his elder brother Pu Shoucheng 蒲壽宬 assisted in building a Taoist-Buddhist temple complex in 1281. This is the period when Pu Shougeng was engaging in vigorous trade under the guise of official overseas missions (Mukai 2008, 135–39).

Basic Data and Previous Studies on the Inscription

The Chinese stone inscription is titled “Zhong jian Qingyuan Chunyang dong ji” 重建清源純陽洞記 (Record of Reconstruction of the Chunyang Cave in Qingyuan Mountain) and dated to the fourth year of Hou-Zhiyuan 後至元 (1338) during the Yuan period. The inscription is carved into the inclined plane of a steep slope behind the Taoist and Buddhist temple complex at Chunyangcave on Qingyuan mountain located in the northeast suburb of the old city of Quanzhou (see figure 1).16

The year 1281 is suggestive because Pu Shougeng dispatched his fleet to overseas countries to expand trade relations under the order of Mongol emperor Khubilai. As mentioned above, Pu Shougeng and Pu Shoucheng are considered to have been Sino-Persian. However, it would have been reasonable for him to do a religious deed for his subordinates, who were mostly Chinese, seemingly practicing Taoism, Buddhism, and worshiping a variety of local deities.

At a first glance, it can be seen as evidence of the intermingling of Taoism and Buddhism in Fujian, and it is well known, however, that there is more to it than that. The origin of worshiping at the Chunyang cave was related to the emergence of new cult religion in that urban area. It was initiated by a charismatic person during the Shaoxing 紹興 years (1131– 1162) of the Song period, though the cult was merged into traditional religions such as Taoism and Buddhism after his death. So, in a sense, the inscription depicted a process of religious integration. As far as I know, this is the first attempt to translate the whole text into English. It is worthy of further research because of its historical value as evidence of religious coexistence and its peculiarity, as mentioned above.

Summary of the Text

First, this section summarizes the contents of the inscription with paragraph numbers 1)-10) attached by the author (see Appendix for the full translation):

-

“Every beautiful and quiet site such as mountains, rivers, rocks, and caves under heaven is the residence of immortal wizards and Buddhist saints. The former exist relying on the latter and the latter manifest depending on the former. They are collaborating with each other in making a mysterious landscape.”

-

During the period of Shaoxing of the Southern Song, an exile practitioner with the surname Pei 裴 came from Jiangdong 江東 (around present-day Nanjing 南京) and lived in a cave in Qingyuan Mountain. He walked around the market every day, wearing a flower made of rice paper pith in his hair and singing a song. Suddenly, he disappeared for several months and nobody knew where he was and later his skeleton was found in the cave. Local people built a shrine to worship him with other deities and hang a tablet saying “chunyang (pure and sunny).”

-

Local people distorted his original teaching and gave wine and food as an offering. They also gathered there to play music and were noisy. Places of lascivious entertainment and bars were even built there. Intellectuals discussed how to stop these practices and decided to build a shrine to Putuo dashi 普陀大士 (Great Master of Potalaka, i.e., Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva) beside the original one to break the evil customs. Following the Shengshan Chan Buddhist temple (Shengshan chan si 昇山禪寺) in Fuzhou 福州, the shrine became the site of Zhenqun’s眞君 (a Taoist deity’s) ascension to heaven.

-

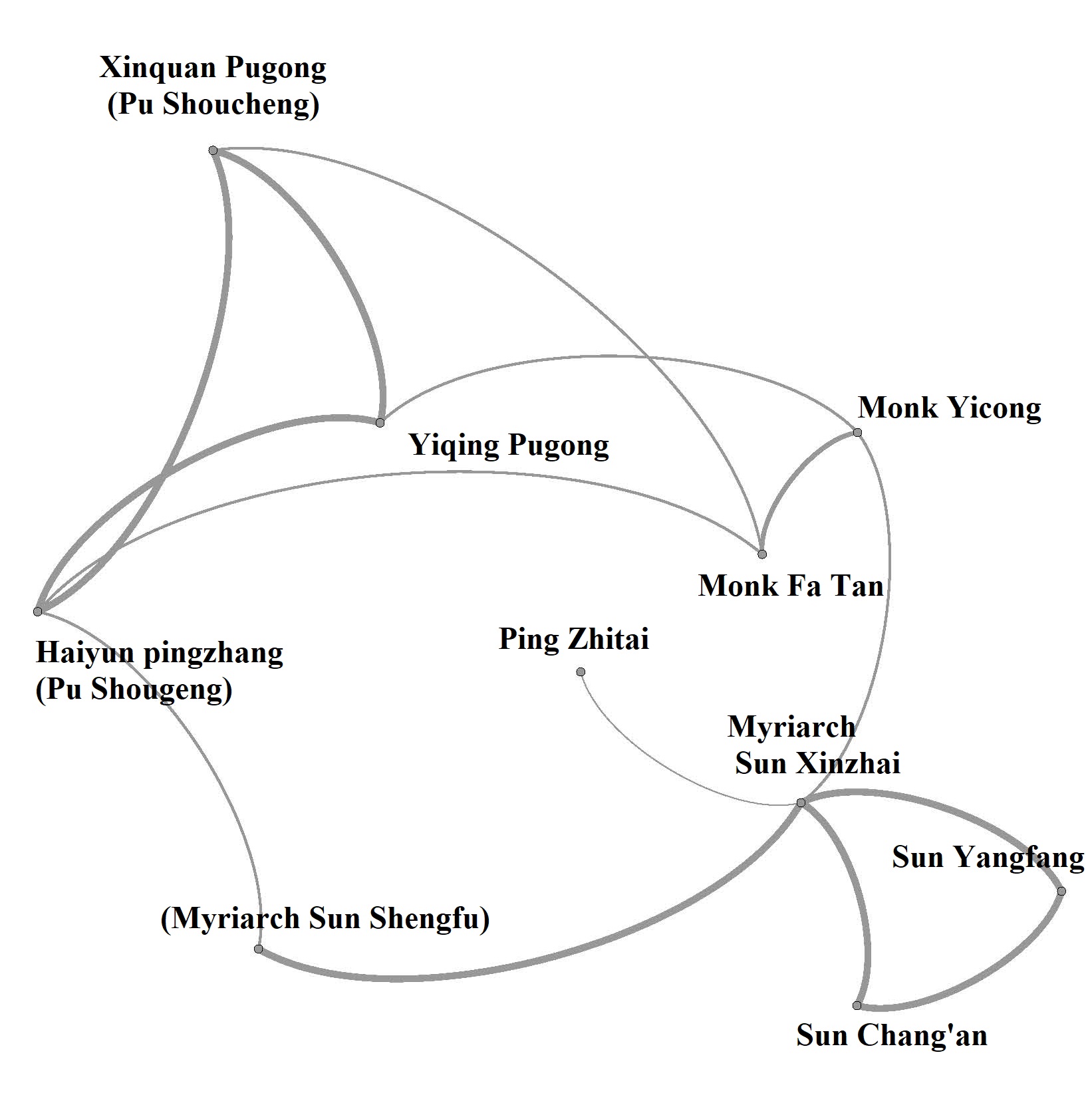

The shrines in Qingyuan Mountain totally burned down during the last years of Southern Song period. In the eighteenth year of Zhiyuan 至元 (1281), a Buddhist monk from Sisong 四松, Fa Tan 法曇, visited the site, swore to restore it, and started the project. Xinquan Pugong 心泉蒲公 (PuShoucheng) and Haiyun pingzhang 海雲平章 (Pu Shougeng)17 provided funds for it and architectural plans were drawn up for a bigger shrine complex than the original one.

-

Twenty-one years later, Tan ordered his leading disciple, Yicong 一聰, to take his place and complete the restoration of the shrine. Stone signboards were erected at thirty points. Several tens of thousands of cedars and pine trees were planted.

-

The restoration project was completed. This could happen because Myriarch Sun Xinzhai (孫信齋) and a grandson of Pu Shoucheng, Pu Yiqing (蒲一卿), had risen in society and got involved in the project.

-

Yicong from Yaolin 瑶林 in Jin yi 晋邑 (Jinjiang 晋江 district) had learned sutras at Sisong and titled himself as Shimen 石門 (“stone gate”). In the fifth month, in the summer of 1333 (the fourth year of Zhishun 至順), Yicong passed away and his whole body was buried at the side of the mountain. When the year 1334 (the second year of Yuantong 元統) passed, the roofs of the Buddhist and Taoist shrines had not been repaired for a long time. Accordingly, it has finally been repaired and the gatehouse was also renewed because it deteriorated and had rain leakage.

-

Lord Sun, who had been preached to by Yicong, possessed an old weir in the Jinjiang district and had it repaired. He spent 220 ding 錠 by Zhongtong chao 中統鈔 (paper money) and built a granary to stock the harvest. He also donated clothes and property for preaching far and wide and bought land and reclaimed it to create new rice fields. He said his good deeds were done following Yicong’s teaching so the credit should go to Yicong. Accordingly, Song required the author Ping Zhitai 平智泰 to compose a full account of the circumstances.

-

Ping Zhitai firmly refused Sun’s request but Sun had never given up and pleaded with Ping again and again. So finally Ping relented.

-

In the tenth month of the fourth year of (Hou-) Zhiyuan (後) 至元 (1338), Wan’an Chan Buddhist temple (Wan’an chan si 萬安禪寺) asked Ping Zhitai to compose this article, and Sun Yanfang 孫彦方 and Sun Chang’an 孫長安 to write (the title of the inscription) in seal script.

An Analysis of the Complexity of Religions

According to the inscription, the cave in Qingyuan Mountain, where practitioner Pei’s skeleton was found, was named Chunyang (Paragraph 2). This shows the Taoist feature of the site for Chunyang was apparently associated with the title Chunyangzi (master Chunyang) of legendary hermit, Lü Dongbin 呂洞賓 (796–1016) of the Tang period. He is one of Eight Immortals worshiped by Taoists. At the same time, the site was also devoted to Buddhism as the shrine for Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva (Putuo dashi) was built (Paragraph 3). These facts exemplify the complex feature of this site.

The inscription claims a situation of coexisting religions and regularizes it in a philosophical way. The following words in the first part of the inscription as well as in the sixth and ninth paragraphs (omitted in the summary above) summarize the theory:

- “The former (immortal wizards) exists relying on the latter (Buddhist saints) and the latter manifests depending on the former. They are collaborating with each other and make a mysterious landscape” (Paragraph 1)

- “Taoism increasingly manifests power depending on the aid of Buddhism” (Paragraph 6)

- “Taoism and Buddhism are the branches stretched from the same stem” (Paragraph 9) Actually, this inscription vividly tells the story of the beginning of the coexistence (to the present time) of a Taoist shrine and Buddhist temple on one site.

Additionally, this inscription attests to the existence of the continuing relationship between Buddhist monks, a Han local elite family, and a Sino-Persian Muslim family in Quanzhou during the Yuan period. These prove the culture of tolerance was highly developed in the Fujian region during the Yuan period. Then what circumstances supported this situation of tolerance among religions shown in this inscription? Is this a very rare situation that occurred only in Fujian? Was this a common phenomenon during the Yuan period?

In the last part of this paper, we will consider these questions as well as how to approach the religious complexity of the period and how to evaluate various ‘external’ conditions. We will consider the following external conditions: Aims and background of the individuals and the social environment of the region.

Aims and Background of the Individuals

As for the personal aims and background behind one’s religious activities and attitudes toward religion, we can imagine the following: (i) to pray for the safety of a voyage, to win peoples’ trust (ensure the religion which is popular among subordinates, crew members, and the local population), and (ii) to be a responsible local governor or member of the elite class.

As mentioned above, Pu Shougeng’s maritime trade under Khubilai’s order is related to the restoration of the Taoist-Buddhist temple complex at Chunyang cave in Qingyuan mountain and it relates to aim (i). In conducting this enterprise, Pu Shougeng utilized his network in a local elite cluster in Quanzhou, in which Han elite Sun Shengfu and his family were included. As shown in the inscription, the relationship between the Sun family and the Pu family lasted for the next two generations. The Sino-Persian Pu family’s commitment to the restoration of the temple complex at Chunyang cave relates to aim (ii) and continued for generations.

Conclusion

This paper has examined the exchange of Islamic, Taoist, and Buddhist religious traditions in Fujian Province, as well as the religious activities and social networks of localized Persian descendants in Quanzhou, Pu Shougeng. The discussion in this paper reveals how people from different religious backgrounds coexisted in South China under Mongol rule and were even involved in the support of the religious community to which they did not belong.

This paper also attempts to show that the degree of contrasting religious coherence can be related to the length of coexistence time of the adherents of these religions in the Fujian region. The results also argued that it is appropriate to distinguish two major types of Islamic belief situations, based on the complex structure of religious harmony in the Quanzhou area under Mongol rule.

- Firm religious traditions: those Muslims who adhere firmly to an apparently pure Islamic faith, as exemplified by the Arabic-language Islamic inscriptions in coastal China. This is observed in the New Islamic Migration from Central and West Asia. Categories (c) and (d)

- Complex religious traditions: Muslims who are apparently mixed with other religions, as seen in the Pu family, are descendants of Persian immigrants in Quanzhou. This is observed in maritime/early syncretic migration/Arab-Persian descendants. Category (b)

A geographical analysis of the restored extent of Pu Shougeng’s residence suggests that he served as an intermediary between the local Han Chinese elite class and Muslim foreigners, mainly Persians.

Based on the above assumptions, we have intensively examined the Yuan-period Qingyuan Mountain Chunyang Cave restoration inscriptions as an example of the religious situation in Category (b). The inscriptions record the contributions of Pu Shougeng and his elder brother in the reconstruction projects undertaken in the early Yuan dynasty and the social network of the Pu family.

The analysis reveals that the relationship between the Pu family, the monks, and the Sun family of Han Chinese who worshiped at this temple continued during the early to mid-Yuan dynasty. This tells us that the Pu clan had strong ties with the local Han Chinese elite class. It was a prerequisite for the Pu family in (b) to serve as an intermediary between foreign Muslims and Han Chinese.

Appendix

Full Translation of “Zhong jian Qingyuan Chunyang dong ji (The Record of Reconstruction of the Chunyang Cave in Qingyuan Mountain, written in the fourth year of Hou-Zhiyuan 後至元 [1338] during the Yuan period)

-

Every beautiful and quiet site, such as mountains, rivers, rocks, and caves, under heaven is the residence of immortal wizards and Buddhist saints. The former exists relying on the latter and the latter manifests depending on the former. They are collaborating with each other to make a mysterious landscape.

-

During the Shaoxing 紹興 years (1131–1162), a practitioner Pei 裴 who came from Jiangdong 江東 province (around Nanjing 南京) stayed in a cave in Qingyuan清源 Mountain. Every day, he wore a flower made of tongcao 通草 (rice paper pith. The scientific name is tetrapanax. It is still used to make artificial flowers in Taiwan today) in his hair and walked around the market while singing a song “Drink three small cups of delicious wine and wear a pretty flower in your hair. Think about things in the past and present (and you know that) to live in peace and joy is better.” Suddenly, Pei disappeared for several months and nobody knew where he was and later a woodcutter found his skeleton in the cave in Qingyuan Mountain. Local people made a statue from his skeleton and established a shrine, hung a tablet saying “Chunyang 純陽 (pure and sunny),” and worshiped it with other deities.

-

People misunderstood Pei’s real intention and gave wine and food as offering, played flute (xiao簫) and five-string lute (zhu 筑) and made loud sounds. Intellectuals sighed and said, “even the seasons and fortune of the mountains and rivers have not yet cycled (i.e. it is not yet time to celebrate and make offerings to the gods of mountains and rivers); they drove the holy ghost to the interior by pressure. How can these acts like building fleshpots (huaguang 花館) and bars (jiutai 酒臺) on the cliff match the teaching of practitioner Pei who emphasized on ‘purity and cleanness (qingjing清浄)’ and the principle of ‘inaction and nature (wuwei無爲)’?” Intellectuals discussed how to stop these practices and decided to build a shrine to worship Putuo dashi 普陀大士 (Great Master of Potalaka, i.e., Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva) beside the original shrine to break the evil customs. Following the Shengshan 昇山chan 禪 Buddhist temple in Fuzhou 福州, the shrine became the site of Zhenqun’s 眞君 (a Taoist deity’s) ascension to heaven.

-

The Qingyuan Mountain totally burned during the last years of Southern Song period and became a habitat of wild monkeys. In the eighteenth year of Zhiyuan 至元 (1281), a Buddhist monk from Sisong 四松 (unknown place name), Fa Tan 法曇, visited the site, swore to restore it. Xinquan Pu gong 心泉蒲公 (Pu Shoucheng 蒲壽宬) and Haiyun pingzhang 海雲平章 (Pu Shougeng 蒲壽庚) provided funds for it and architectural plan was enlarged to ten or hundred times the original one.

-

Twenty-one years later, Tan ordered his leading disciple Yicong 一聰 to succeed his master’s position and complete the restoration of the shrine. Soon after the restoration project started, a typhoon came and timber supply dried up. However, Cong encouraged himself to carry out the task of his master’s wish. He stayed diligent to the will and was never indolent. Therefore, some years later, very quickly, the building was completely renovated. To house four devas (sidabu 四大部), they have got a pavilion (ge 閣). To contain…(blank)…, it has got a hall (tang 堂). Subsequently, Yingzhen 應眞 (“respond the truth”) pavilion and Guangkong 觀空 (“see the śūnya”) skyscraper (lou 樓) were built. Stone signboards (shiji 石記) were erected at thirty points. Several tens of thousands of cedars (shan 杉) and pine trees (song 松) were planted and a surrounding stone wall (shiyong 石墉) of two thousand zhang 丈 (6,144m) was built to prevent a forest fire. Further, he reclaimed more than twenty columns (duan 段) of new rice field and performed a ritual of agriculture in spring (zhengchang 蒸嘗, ancient Chinese ceremony to pray for the good crop). Total (area?) of rice field for lent within the area circled by the stone signboards does not differ from those of other temples.

-

One day, when light clouds were in the sky, I wandered on the balcony along the handrail, reciting a poem and expressing emotion and when I swept the landscape a thousand miles from there, I could see the mountains lying on top of one another and looking like big and small banners. Fogs were curling up and floating like a man bowing and creeping. Rivers joined together and flowed into the sea and brought a high tide looking like a blue gem (tiqingbao 帝青寶, Indranilamuktā) or a glass (liuli 琉璃). Vessels and seagulls appeared and disappeared in the wide ocean and in the empty sky. Likewise, distant view and foreground, high view and low view all mingled to create thousands of different sceneries. Men like Wang Mojie 王摩詰 (Wang Wei 王維, Tang period poet) and Guo Xi 郭熙 (Song period painter) had had emotional strain and shoulder dislocation from their busy writings and paintings though they are edited and compiled but not rewarded. Seeing fine monasteries clustered in this mountain, their clean, bright, and magnificent sight was never inferior to that of the Imperial capital (jing 京). Oh, did not what Cong 聰 (Yicong) accomplished add much to that of his master? It mostly depends on the cycle of fortune being favorable to him. Because the timing was ideal at that time, Taoism manifested more and more power depending on the aid of Buddhism. In addition, this could happen because Xinzhai wanhu (Myriarch) Sun gong 信齋萬戸孫公 (SunXinzhai 孫信齋) and a grandson of Pu Shoucheng, Yiqing Pu gong 一卿蒲公 (Pu Yiqing蒲一卿), had risen in society and got involved in the project.

-

Cong (Yicong) was from Yaolin 瑶林 (“limestone cave”) in Jin yi 晋邑 (probably Jinjiang 晋江 district, Quanzhou). He had learned sutras at Sisong and titled himself as Shimen 石門 (“stone gate”). He had lived in the mountain for more than thirty years and knew his limit and was content with it. He practiced asceticism and did a good deed and the people of the day regard him as an enlightened. In the year of gengwu 庚午 (1330, the third year of Tianli 天暦), Cong told his adherent Qi Yin to manage the cave. On the fifth month, in the summer of the year of guiyou 癸酉 (1333, the fourth year of Zhishun 至順), Cong passed away and his whole body was buried in the side of the mountain. When the year of jiaxu 甲戌 (1334, the second year of Yuantong 元統) passed, the roofs of Buddhist and Taoist shrine had not been repaired for a long time. Accordingly, it was finally repaired, and the gate house was also renewed because it had deteriorated and had rain leakage.

-

There was Sun fu 孫府 (lord Sun) who had been preached to by Cong (Yicong). He possessed an old weir (dai 埭) at Dongshan 東山 (“east hill”) du 渡 (ferry) in the thirtieth du 都 (ward) of Jinjiang晋江 xian 縣 district and he repaired it and was provided twenty dan 石 (1,898 l) of seed. He spent 220 ding 錠 (a unit of money originated from a unit of weight, corresponding to about 2 kg [of silver]) by Zhongtong chao 中統鈔 (paper money) and built a granary to stock the harvest. He also donated clothes and property for preaching in all directions and bought more than 450 mu 畝 (2,548 a) of land in the thirty ninth, forty first, and forty second du (ward), which were reclaimed to be new rice fields. The good deeds were done following Cong’s teaching, so the credit should go to Cong. Accordingly, Sun required me (Ping Zhitai 平智泰) to compose a full account of the circumstances.

-

I firmly refused Sun’s request and said, “Sir Fu (Fu gong 傅公), teacher Youxiang (Youxiang xiansheng 有郷先生), previously wrote the account of the meritorious deed of master Tang 曇 (Tang shi 曇師, i.e. Fatang 法曇). Now you asked me instead of the famed writer of the day to write about the achievement of your master. How can I demonstrate my writing skills and make people believe in my qualifications for this task?” Nevertheless, Sun had never relented and pleaded with me again and again. So that finally I told him, “This mountain of rocks and caves is the home of wizards and it is a calm and scenic place. I would not mention every detail because local people know that this is the top of scenic sites in the city of Quanzhou. If one would live a carefree life out of this world, declining offers from royalty, being mingled with birds and beasts, and farming for enjoying self-sufficiency, this is the ideal place for retirement at leisure. We have originally taken this as the ultimate law? Proclaiming new land is to clarify the profound truth of ancestors. Planting pine trees is to shine master Shimen’s deep intention: that is, awakening the theory of “qingjing (purity and cleanness),” “‘wuwei (what is so of itself)” and understanding that Taoism and Buddhism are the branches stretched from the same stem. If I correctly got your master’s thought, it can be said that every single bamboo tree, wood, hand of water, stone, all these eternal things of nature are need not be inscribed. This is why I omit superficial, shallow words, and let them be handed down to the future forever.

-

In the tenth month in autumn of the year of wuyan 戊寅, the fourth year of (Hou-)Zhiyuan (後) 至元 of Dayuan 大元 dynasty (1338), Wan’an Chan temple (Wan’an chan si萬安禪寺) used the article composed by Ping Zhitai, the lord of Zhuangmin (Zhuangmin hou 壯敏侯), Sun Yanfang 孫彦方 and Sun Chang’an 孫長安 wrote (the title) in seal script.

References

Buell, Paul D. 2003. Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press.

Chen Dasheng, and Ludvik Kalus. 1991. Corpus d’Inscriptions Arabes et Persanes en Chine 1 Province de Fu-jian (Quan-zhou, Fu-zhou, Xia-men) [Corpus of the Arabic and Persian Inscriptions in China 1 Fujian Province (Quanzhou, Fuzhou, Xiamen)]. Genève: Foundation Max van Berchem.

Chen Dasheng 陳達生. 1984. Quanzhou yisilanjiao shike 泉州伊斯蘭教石刻 [Quanzhou Islamic Inscriptions]. Edited by Fujiansheng Quanzhou haiwai jiaotongshi bowuguan 福建省泉州海外交通史博物館. Translated by Chen Enming 陳恩明. Fuzhou 福州: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe 福建人民出版社 [Fujian People’s Publishing House].

Chen Gaohua 陳高華. 1987. “Pu Shougeng shiji 蒲壽庚事跡 [An Evidence on Pu Shougeng].” Zhongguo shi yanjiu 中国史研究 [Journal of Chinese historical studies] 1978 (1).

Clark, Hugh. 2006. “The Religious Culture of Southern Fujian, 750–1450: Preliminary Reflections on Contacts Across a Maritime Frontier.” Asia Major (Third Series) 19 (1/2): 211–40.

Deeg, Max. 2018. Die Stiele von Xi’an [The Radiant Religion: the Stele from Xi‘an]. Wien: Lit.

Ding Hesheng 丁荷生 (Kenneth Dean), and Zheng Zhenman 鄭振滿, eds. 2003. Fujian zongjiao beaming huibian, quanzhoufu fence 福建宗教碑銘彙編, 泉州府分冊 [Epigraphical Materials on the History of Religion in Fujian: Quanzhou Region]. Vol. 1. Fuzhou 福州: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe 福建人民出版社 [Fujian People’s Publishing House].

Ebert, J. 2004. “Segmentum and Clavus in Manichaean Garments of the Turfan Oasis.” In Turfan Revisited, edited by D. Durkin-Meisterernst, Simone Ch. Raschmann, and Jens Wilkins, 21:72–83. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

Fan Ke. 2001. “Maritime Muslims and Hui Identity: A South Fujian Case.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 21 (2): 309–32.

Fei lang 費琅 (Gabriel Ferrand). 2002. Kunlun ji nanhai gudai hangxing kao; Sumendala guguo kao 崑崙暨南海古代航行考; 蘇門答剌古國考 [Le K’ouen-Louen et les Anciennes Navigations Interoceaniques dans les Mers du Sud; L’empire Sumatranais de Çrīvijaya]. Translated by Feng Chengjun 馮承鈞. Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局 [Zhonghua Book Company].

Ferrand, Gabriel. 1922. “L’empire Sumatranais de Çrīvijaya.” Journal Asiatique (IIe Série) 20: 1–85, 61–246.

Forte, Antonino. 1999. “Iranians in China: Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Bureaus of Commerce.” Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 11: 277–90.

Fujian sheng Quanzhou shi diming bangongshi 福建省泉州市地名辦公室 [Place Name Office in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province], ed. 1982. Fujian sheng Quanzhou shi diming lu 福建省泉州市地名錄 [Record of Place Names in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province]. Quanzhou 泉州.

Fujita, Toyohachi 藤田豊八. 1917. “Sōdai no shihakushi oyobi shihaku jōrei 宋代の市舶司及び市舶條例 [Customs Offices (Shibosi) and Maritime Trade Regulation during the Song period].” The Toyo Gakuho 東洋学報 7 (2): 150–246.

Gardner, Iain, Samuel Lieu, and Ken Parry. 2005. From Palmyra to Zayton: Epigraphy and Iconography. Turnhout: Brepols.

Gernet, Jacques. 1991. Chine et Christianisme: La première confrontation [China and Christianism: The First Confrontation]. Édition revue et corrigée. Paris: Gallimard.

Guojia Tushuguan Shanben Jinshi Zu 國家圖書館善本金石組 [Manuscripts and Inscriptions Division, National Library of China], ed. 2003. Liao, Jin, Yuan shike wenxian quanbian 遼金元石刻文獻全編 [Collection of Inscriptions of Liao, Jin, Yuan Periods]. Vols. 1-3. Beijing: Beijing Tushuguan Chubanshe 北京圖書館出版社 [National Library of China Publishing House].

Hong Shaolu 洪少禄. 1983. “Quanzhou shi fou you ‘fanfang’ 泉州是否有‘蕃坊’ [Did Quanzhou have ‘fanfang (foreign settlement) or not].” In Quanzhou haiwai jiaotong shiliao huibian 泉州海外交通史料滙編 [Collection of Historical Sources on Overseas Contacts at Quanzhou], edited by Zhongguo haiwai jiaotongshi yanjiuhui, Fujian sheng Quanzhou haiwai jiaotong shi bowuguan 中國海外交通史研究會, 福建省泉州海外交通史博物館 [The Museum of the History of Overseas Contacts at Quanzhou], 6:239–42. Quanzhou 泉州: Jinjiang Diqu Yinshua Chang 晋江地區印刷廠 [Jinjiang Region Printing Factory].

Huai Yinbu 懐蔭布, Huang Ren黄任, and Guo Gengwu 郭賡武, eds. (1763) 2000. Qianlong Quanzhou fuzhi 乾隆泉州府志 [Local Gazetteer of Quanzhou Province]. 76 vols. Quanzhouzhi: Quanzhouzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui bangongshi 泉州志編纂委員会辦公室. Reprint. Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian Chubanshe 上海書店出版社 [Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House].

Huang Zhongzhao 黄仲昭, ed. (1489) 1989. Ba Min tongzhi 八閩通志 [Local Gazetteer of Ba Min (Fujian)]. Fuzhou: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe 福建人民出版社 [People’s Publishing House].

Ibn Baṭṭūṭa. 1994. The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa A.D.1325–1354. Translated by H. A. R. Gibb and C. F. Beckingham. Vol. 4. London: The Hakluyt Society.

Israeli, Raphael. 2000. “Medieval Muslim Travelers to China.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 20 (2): 314–21.

Kauz, Ralph. 2010. “A Kāzarūnī Network?” In Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea, edited by Ralph Kauz, 61–69. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Kawagoe, Yasuhiro. 1977. “Iwayuru Teiwa gyōkahi nit suite 所謂鄭和行香碑について [On the ‘Zheng He Burning Incense Inscription’].” In Nakayama Hachirō kyōju shōju kinen Min Shin shi ronsō 中山八郎教授頌壽記念明清史論叢 [The Collected Papers on Ming–Qing History in Commemoration of the Longevity Celebration of Professor Nakayama Hachirō], edited by Shigeo Sakuma 佐久間重男 and Yukio Yamane 山根幸夫. Tokyo: Ryōgen shoten 燎原書店.

Kuwabara, Jitsuzo 桑原隲蔵. 1989. Hojukō no jiseki 蒲壽庚の事蹟 [On Pu Shougeng]. Tokyo: Heibonsha 平凡社.

Leslie, Donald Daniel. 1986. Islam in Traditional China: A Short History to 1800. Canberra: Canberra College of Advanced Education.

———. 1998. The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims. George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology 59. Canberra.

Lieu, Samuel N. C. 1998. Manichaeism in Central Asia and China. Brill.

Lieu, Samuel N. C., Lance Eccle, Majella Franzmann, Iain Gardner, and Ken Parry. 2012. Medieval Christian and Manichaean Remains from Quanzhou (Zayton). Corpus Fontinum Manichaeorum: Series Archaeologica et Iconographica 2. Turnhout: Brepols.

Lin Song. (1988) 2004. “Lun Zheng He de Yisilanjiao Xinyang: Qian ping Zheng shi ‘feng fo’, ‘chong dao’ shuo 論鄭和的伊斯蘭教信仰: 淺評鄭氏‘奉佛’ ‘崇道’説 [Arguments on Zheng He’s Belief in Islam: With Estimation of Zheng Family’s Belief in Buddhism and Taoism].” In Zheng He yanjiu bainian lunwen xuan 鄭和研究百年論文選 [Selected Articles of 100 Years Zheng He Studies], edited by Wang Tianyou and Wan Ming. Beijing: Daxue Chubanshe 北京大学出版社 [Peking University Press].

Liu Yingsheng 劉迎勝. 2015. “Youguan Songmo Quanzhou Pushi shiliao de ji ge yidian 有關宋末泉州蒲氏史料的幾個疑点 [Questions on the Sources of the Quanzhou’s Pu Family in the Late Song Period].” In Yuanshi ji minzu yu bianjiang yanjiu jigan 元史暨民族辺疆研究集刊 [Studies on the Mongol-Yuan and China’s Bordering Area], edited by Liu Yingsheng 劉迎勝 et al. Vol. 30. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社 [Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House].

Li Zhengru 李正儒, ed. (1534) 1968. Gaocheng xian zhi 藳城縣志 [Local Gazetteer of Gaocheng district]. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe 成文出版社.

Maejima, Shinji 前嶋信次. 1952. “Senshū no Hashi-jin to Hojukō 泉州の波斯人と蒲壽庚 [The Persians in Ch’uan-chou and P’ushou-K’ang].” Shigaku 史學 25 (3): 1–66.

Moriyasu, Takao 森安孝夫. 1997. “Uiguru moji shinkō: Kaikai meishō mondai kaiketsu heno ichi soseki ウイグル文字新考: 回回名称問題解決への一礎石 [A New Study of the Uighur Script : A Foundation for Solving the Problem of the Designation Hui-hui].” In Tōhō-gakkai sōritsu gojū shū nen kinen, Tōhōgaku ronshū 東方学会創立五十周年記念東方学論集 [“Eastern Studies” Fiftieth Anniversary Volume], 1238–26 (reverse page). Tokyo: Tōhō-gakkai 東方学会 [The Toho Gakkai].

Mukai, Masaki 向正樹. 2002. “Mongoru jidai senshū no seijōji shūchiku ni tsuite モンゴル時代泉州の清浄寺修築について [The Restorations of the Qingjingsi Mosque in Quanzhou during the Mongol period].” Kansai Arabu Isuramu Kenkyu 関西アラブ・イスラム研究 [Kansai Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies] 2: 89–105.

———. 2007. “Hojukō gunji shūdan to Mongoru kaijō seiryoku no taitō 蒲壽庚軍事集団とモンゴル海上勢力の抬頭 [The Role of Pu Shogeng’s Private Militia in the Emergence of Mongol Sea Power].” The Toyo Gakuho 東洋學報 89 (3): 327–56.

———. 2008. “Kubirai-Chō Shoki Nankai Shōyu No Jitsuzō: Senshū Ni Okeru Gunji-Kōeki Shūdan to Konekushon クビライ朝初期南海招諭の實像: 泉州における軍事・交易集団とコネクション [Another Aspect of the Legation to the Southern Seas During the Early Part of Khubilai’s Reign: Military and Trade Groups and Their Connections].” Tohogaku 東方學 116: 127–45.

———. 2009. “Mongoru chika Fukken enkaibu no Musurimu kanjin-sō モンゴル治下福建沿海部のムスリム官人層 [Muslim Officials in Fujian Coastal Region during the Yuan Period].” Arabu-isuramu kenkyu アラブ・イスラム研究 [Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies] 7: 79–94.

———. 2010. “The Interests of the Rulers, Agents and Merchants behind the Southward Expansion of the Yuan Dynasty.” Edited by Academia Turfanica. Journal of the Turfan Studies: Essays on the third International Conference on Turfan Studies the Origins and Migrations of Eurasian Nomadic Peoples, 428–45.

Niu Ruji 牛汝極. 2008. Shizi lianhua: Zhongguo Yuandai Xuliya wen beaming wenxian yanjiu * 十字蓮華: 中国元代叙利亜文景教碑銘文献研究 [The Cross-lotus: A Study on Nestorian Inscriptions and Documents from Yuan Dynasty in China]*. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社 [Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House].

Quanzhou haiwai jiaotongshi bowuguan, Quanzhoushi Quanzhou lishi yanjiuhui 泉州海外交通史博物館, 泉州歴史研究會 [The Museum of the History of Overseas Contacts at Quanzhou, Quanzhou History Research Association]. 1983. Quanzhou Yisilan yanjiu lunwenxuan 泉州伊斯蘭研究論文選 [Selected Articles on Islam in Quanzhou]. Fuzhou: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe 福建人民出版社 [Fujian People’s Publishing House].

Rossabi, Morris. 1981. “The Muslims in the Early Yüan Dynasty.” In China Under Mongol Rule, edited by John D. Langlois, Jr, Reprint, 257–95. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

———. 1989. “Islam in China.” In Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade, 223–49. New York: Macmillan.

Schottenhammer, Angela. 2015. “China’s Gate to the South: Iranian and Arab Merchant Networks in Guangzhou During the Tang-Song Transition (C. 750–1050), Part II: 900–C. 1050.” AAS Working Papers in Social Anthropology 29: 1–28.

So, Billy K. L. 2000. Prosperity, Region, and Institutions in Maritime China: The South Fukien Pattern, 946–1368. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

So, Keelong 蘇基朗 (Billy So K. L.). 1991. “Lun Pu Shougeng jiang Yuan yu Quanzhou difang shili de guanxi 論蒲壽庚降元與泉州地方勢力的關係 [The Arguments on the Relation between Pu Shougeng’s Surrender to the Yuan and Local Powers in Quanzhou].” In Tang Song shidai Minnan Quanzhou shidi lungao 唐宋時代閩南泉州史地論稿 [The Historical and Geographical Studies on Minnan Region and Quanzhou during the Tang and Song period], edited by Keelong So, 1–35. Taipei: Taiwan Shangwu Yinshuguan 臺灣商務印書館 [Taiwan Shangwu Yinshuguan Press].

Song Lian 宋濂. (1369) 1978. Yuan shi 元史 [The Official History of the Yuan]. 15 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局 [Zhonghua Book Company].

Sugimoto Naojirō 杉本直治郎. 1952. “Hojukō no kokuseki mondai 蒲壽庚の國籍問題 [On the Nationality of P’u-shou-kêng].” Toyoshi kenkyu 東洋史研究 [The Journal of Oriental Researches] 11 (5-6): 476.

Tazaka, Kodo 田坂興道. 1964. Chūgoku ni okeru kaikyō no denrai to sono kōtsū 中國における回教の傳來とその弘通 [Islam in China its introduction and development]. 2 vols. Tokyo: Toyo Bunko 東洋文庫.

Vermeer, Eduard B. 1991. Chinese Local History: Stone Inscriptions from Fukien in the Sung to Ch’ing Periods. Boulder: Westview Press.

Wade, Geoff. 2010. “The Li (李) and Pu (蒲) ‘Surnames’ in East Asia-Middle East Maritime Silkroad Interactions during the 10th–12th Centuries.” In Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea, edited by Ralph Kauz, 181–93. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Wang Dayuan 汪大淵. (1350) 1981. Daoyi zhilüe jiaoshi 島夷誌略校釋 [Edited and Noted Text of Daoyi zhilüe]. Edited by Su Jiqing 蘇繼廎. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局 [Zhonghua Book Company].

Wu Jianwei 呉建偉, ed. 1995. Zhongguo qingjingsi zonglan 中國清眞寺綜覧 [Complete List of Mosques in China]. Yinchuan: Ningxia Renmin Chubanshe 寧夏人民出版社 [Ningxia People’s Publishing House].

Wu Wenliang 呉文良. 1957. Quanzhou zongjiao shike 泉州宗教石刻 [Quanzhou Religious Inscriptions]. Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe 科學出版社 [Science Press].

Wu Youxiong 呉幼雄. 1988. “Yuandai Quanzhou ba ci she xing yu Pu Shougeng ren Quanzhou xingsheng pingzhangzhengshi kao 元代泉州八次設省與蒲壽庚任泉州行省平章政事考 [Examination of the Fact of Eight-times Reestablishments of Mobile Secretariat at Quanzhou and Pu Shougeng’s Appointment as Governor].” Fujian luntan (wen-, shi-, zhe-ban) 福建論壇 (文・史・哲版) [Fujian Tribune (The Humanities & Social Sciences] 1988.2 (gen. no. 45): 43–46.

Xu Xiaowang 徐暁望. 2006. Fujian tongshi 福建通史 [The History of Fujian]. 5 vols. Fuzhou: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe 福建人民出版社 [Fujian People’s Publishing House].

Yang Zhijiu 楊志玖. 2003. Yuandai Huizu shi gao 元代回族史稿 [A Study of the Hui Nationality in the Yuan Dynasty: Its Formation and Humanics]. Tianjin 天津: Naikai Daxue Chubanshe 南開大学出版社 [Nankai University Press].

Yoshida Yutaka 吉田豊, and Furukawa Shoichi 古川攝. 2015. Chūgoku Kōnan Mani-Kyō Kaiga Kenkyū 中国江南マニ教絵画研究 [Studies of the Chinese Manichaean Paintings of South Chinese Origin Preserved in Japan]. Kyoto: Rinsen shoten.

Zhuang Jinghui 莊景輝. 1988. “Quanzhou Luocheng-Zhi Kaobian 泉州羅城址考辯 [Consideration on the Site of the Outer Wall of Quanzhou].” Haijiaoshi Yanjiu 海交史研究 [Research in the History of Sea Communication] 1988.2 (gen. no. 14): 118, 119–26.

Zurcher, Erik. 2007. The Buddhist Conquest of China. The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. Leiden: Brill.

Unlike other regions in China, Confucianism never had a hegemonic position in Fujian, where Shamanism, Taoism, and Buddhism had a longer tradition and the status of each religion was more equal (Xu 2006, 1:229–243). As for previous studies on the history of the introduction of foreign religions into China in general, the case of Buddhism (Zurcher 2007), Manichaeism (Lieu 1998), and Christianity (Gernet 1991; Gardner, Lieu, and Parry 2005; Niu 2008; Deeg 2018) in China was studied, while no such comprehensive research was done on the relationships between Islam, Confucianism, and Taoism, which is the major focus of this paper.↩︎

This cao’an was known to have existed there since the Mongol period and Samuel N. C. Lieu recently introduced a document on the foundation of this shrine dedicated to Mani in 1148 (Lieu et al. 2012, 74). The present cao’an, a typical Minnan 閩南 (South Fujian) style building, was renovated in the early part of the last century (between 1923 and 1932), and there is no trace of the original building “when it was used by the Manichaeans in the hey day of the sect in the fourteenth century” (Gardner, Lieu, and Parry 2005, 205; Lieu et al. 2012, 80).↩︎

Many scholars discussed this topic almost at the same time. An extensive bibliography list of research literature before March 2014 was prepared by Gábor Kósa and published in the article by Yoshida Yutaka (2015, 82–86).↩︎

Fujita Toyohachi 藤田豊八 (1917) and Kuwabara Jitsuzo 桑原隲蔵 (1989) published pioneering studies on the early history of maritime trade and foreigners in China. Maejima Shinji 前嶋信次 pointed out that the biggest portion of Islamic immigrants in this region were Persians (1952). Comprehensive studies on Islam in China in general were published by Tazaka Kodo 田坂興道 (1964), Donald Leslie (1986, 1998), and Morris Rossabi (1981, 1989) . Many other important works were compiled by Quanzhou haiwai jiaotongshi bowuguan 泉州海外交通史博物館 (1983) and Quanzhoushi Quanzhou lishi yanjiuhui 泉州市泉州歴史研究會 [The Museum of the History of Overseas Contacts at Quanzhou, Quanzhou History Research Association] (1983).↩︎

The surname Pu was considered to be derived from kunya (an element of an Arabic personal name) Abū, which means “father” in Arabic, while others regarded the Pu family as of Cham origin. Pu corresponded to the title of a nobleman in Malay-Polynesian languages, that is, Pu or Mpu (Ferrand 1922; Fei 2002, 82). Sugimoto Naojiro 杉本直治郎 compared the two theories and disregarded the theory of the Cham origin (1952).↩︎

These epigraphic sources written by early Yuan literati, Wang Pan, and titled “Gaocheng ling Dong Wenbing yi’aibei” 藳城令董文炳遺愛碑 [Memorial Stone Tablet for District Governor of Gaocheng, Dong Wenbing]” (in Li [1534] 1968, Ch. 8) and “Zhaoguo Zhongxian gong shendaobei 趙國忠獻公神道碑 [Inscription on the Avenue to the Grave of Lord Zhongxian in Zhao country]” (in Li [1534] 1968, Ch. 9) survived in Gaocheng xian zhi 藳城縣志 [Local Gazetteer of Gaocheng district] published in 1534, and Chen Gaohua 陳高華 introduced them (Chen 1987).↩︎

In Chinese official historiography, such as Xin Tangshu 新唐書, written during the Song period, Huihe originally meant Uighur and the majority of them were not Muslims but Buddhists and Christians during the Yuan period. For honorific biographical works, Wang Pan probably preferred to use the more classic and elegant word Huihe instead of Huihui 回回, which meant Muslim during the Yuan period. In Yuan shi 元史, Ch. 205 (Song [1369] 1978, 4558), Muslim financial minister Ahema 阿合馬 (Ahmad) of Khubilai’s reign was also written to be a Huihe. On the problem of the designation Huihui, see Moriyasu (1997).↩︎

One of the indications of the Pu family in Quanzhou adhering to the Islamic tradition, as mentioned above in this paper is the stone stele built by Pu Heri beside the tomb of Muslim sages in the Linshan Muslim Cemetery in Eastern Quanzhou, which commemorated admiral Zheng He’s visit in 1417 on his way to the “Western Ocean.”↩︎

All maps and graphs in this article were created by the author.↩︎

According to Ralph Kauz, Burhān al-Dīn’s arrival at Quanzhou was in the year 1312 (Kauz 2010, 68).↩︎

The length of each term is uneven because the data is only available for the reigns of emperors. Fuzhou lacks records from officials after 1333.↩︎

An example of (b) is the Sino-Persian merchant at Quanzhou Pu Shougeng, as well as his son Pu Shiwen 蒲師文, who was appointed to be the governor (pingzhang zhengshi) of the mobile secretariat of Fujian in the early Yuan period.↩︎

During the Song and Yuan period, Quanzhou did not have a foreign settlement (officially allotted exclusive quarter for foreigners) such as the fanfang 蕃坊 of the Tang period in China (Hong 1983).↩︎

For the text of the inscription, see Chen Dasheng 陳達生 (1984), for the translation into English, see Vermeer (1991, 121–27).↩︎

The classical Chinese term semu 色目 means “various categories.” The semuren were one of the legally-defined social groupings unique to Mongol China. They were generally Central Asians and Westerners and ranked just below the Mongols (Buell 2003, 240).↩︎

The text of the inscription is, in large part, not visible and hard to decipher now but it was recorded in Chen Qiren 陳棨仁 (1836–1903), Minzhong jinshi lü 閩中金石略, Ch. 12, n.d. and Fujian tongzhi zu 福建通志組 ed.Fujian jinshi zhi 福建金石志, Ch. 13 in 1922 (both reprinted in Guojia 2003, vols. 1-3, vol. 3). By depending on these records only, we can read the whole text. The inscription was cited by Wu Yongxiong 呉幼雄 as one of the epigraphic sources in determining the periodical changes of the Mobile Secretariat in Fujian during the Yuan period (1988). Now the whole text has been published in print (Ding 2003, 1:53–54).↩︎

Pu Shoucheng had a courtesy name Xinquan 心泉, as his anthology was titled Xinquan xue shi gao 心泉学詩稿, 6 vols. Pu Shougeng had a coutesy name Haiyun 海雲. As mentioned above, he bore the title pinzhang because he was appointed pingzhang zhengshi (governor) of the Mobile Secretariat (xingsheng) at Quanzhou (see Wu 1988).↩︎

See “Wu xu [Preface written by Wu (Jian)]” of Wang Dayuan, Daoyizhilue ([1350] 1981, 5) and Song Lian, Yuan shi, Ch. 11 ([1369] 1978, 235).↩︎

See Huang Zhongzhao 黄仲昭, Ba Min tongzhi 八閩通志, Ch. 32 ([1489] 1989, 686). According to the note, Sun Tian was modified to be Sun Tianyou 孫天有 in Huai Yinbu 懐蔭布 et al., Qianlong Quanzhou fuzhi 乾隆泉州府志 ([1489] 1989, 689).↩︎