Of Hypocrites, Whores, and Holy Animal Bones

Polemical Comparisons and the Invective Mode in Early Reformation Disputes

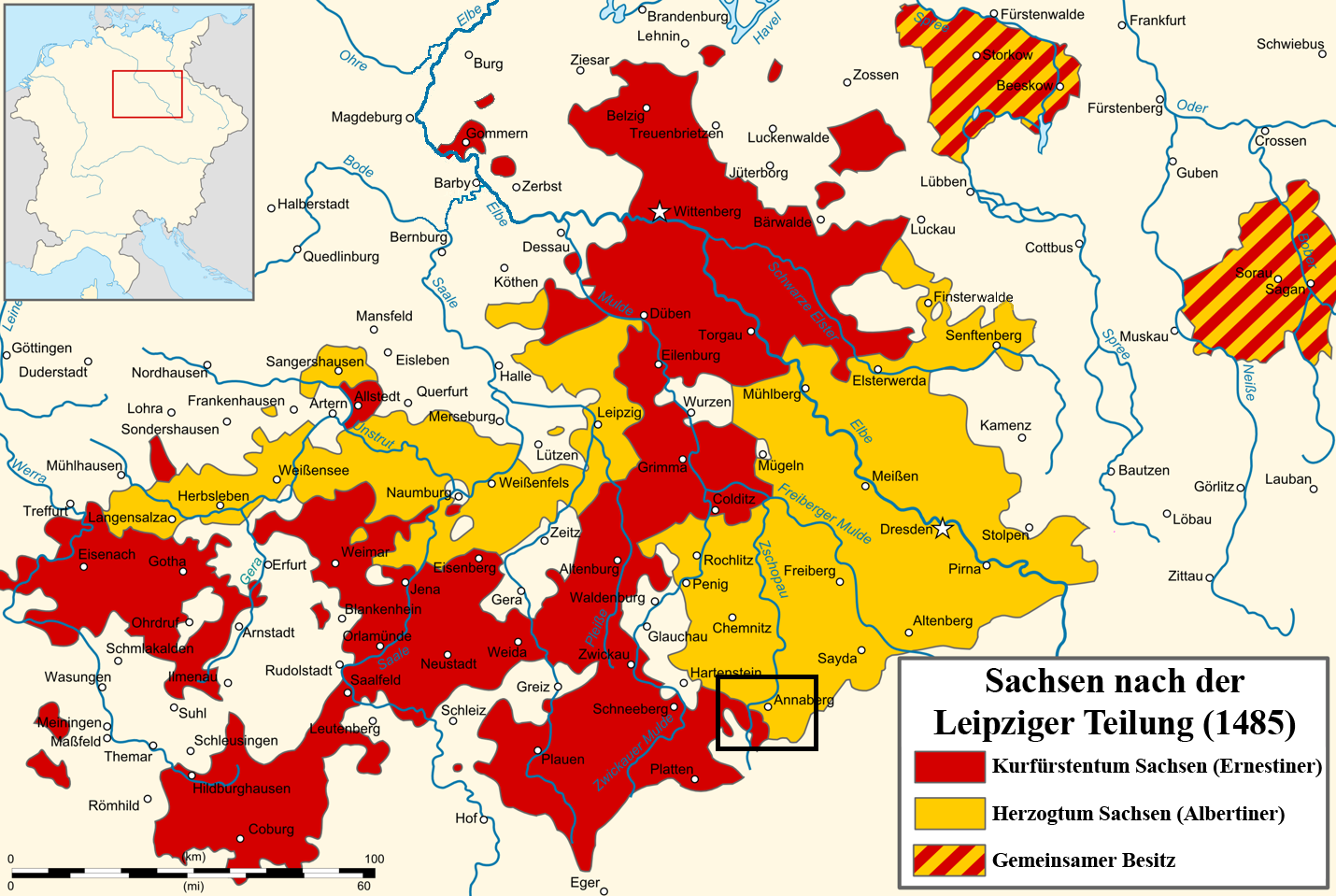

This article aims to illustrate how a pervasively invective mode of communication was pivotal for early Reformation disputes. For this purpose, it explores, first, specific techniques of polemical comparison used in invective communication. Second, it analyses the relation between a broader transregional public discourse and debates at the local level. Some of the sources examined in this article, for instance a handwritten pasquinade whose anonymous author fiercely criticized a Franciscan preacher, as well as a creatively adapted letter of indulgence, are new to Reformation research. The objective here is to outline decisive and entangled aspects of (semi-)public communication between 1520 and 1524. In order to do so, I focus on the beginning of early Reformation conflicts, their ongoing volatility, and their performative zenith, along the border of two of the most important German territories at the time—the Ernestine Electorate and the Albertine Duchy of Saxony.

invective mode, pamphlets, polemic, public sphere, Reformation, Saxony

1. Introduction

During the second half of 1524 a remarkable mock procession in a small Saxon mining town became famous throughout the Holy Roman Empire. A narration of the event was printed in three different editions as On the Right Elevation of Benno (Von der rechten erhebung Bennonis) and also turned into a rhymed song.1 Probably in mid-July 1524 (although the exact date is still disputed today), a group of young pikemen from ‘St. Catharinenberg im Buchholz’ (hereafter Buchholz) ridiculed and rambunctiously satirized and lampooned the veneration of Saint Benno of Meißen, which had taken place on June 16, 1524.2 The Buchholz event, therefore, is closely associated with and almost as well known as the elevation of St Benno in Meißen, which appeared to be the contested canonization—to use Ronald Finucane’s phrase—of the last medieval saint at the cusp of the early modern period (Finucane 2011, esp. chap. 6). Even though it had been planned well in advance, the veneration of St Benno was not performed in a pre-Reformation context, instead becoming another and in this case highly symbolic battleground. The printed reports about the Buchholz mock procession have been widely cited in chronicles as well as in Reformation historiography since the sixteenth century.3 However, no researcher has yet asked why this event occurred exactly at this time in this particular, and rather inconspicuous, town, when outrage about the canonization of St Benno, inflamed by Martin Luther himself (1524), was widespread throughout Germany (see Dänhardt 2017). Some early Reformation events and incidents in this particular region might be less known than expected and we should not simply take an event like the Buchholz mock procession for granted just because we know it happened.

This article therefore aims to reconsider such events from a perspective that takes the entangled history and overlapping relations in borderlands—above all the zone linking the Ernestine Electorate and the Albertine Duchy of Saxony—more seriously than previous scholars have done. To this end, some more or less well-known sources are reinterpreted to uncover hidden clues and read alongside hitherto neglected sources to shed more light on religious disputes and the dynamic communication between the important Albertine mining city of St. Annaberg (hereafter Annaberg) and the far smaller neighboring Ernestine town of Buchholz, both of which are today the municipality of Annaberg-Buchholz (figure 1). Of primary interest is the mode of communication within this very narrow microcosm of the Reformation public sphere, which included both a disparaging use of language and practices of mocking, slander, and defamation. Since these communicative practices were neither bound to specific genres nor styles like polemic, the concept of invective mode is applied to analyze the dynamics and consequences of interwoven invective communication in this region during the first years of the Reformation. Of recent origin, the concept of ‘invective mode’ has been outlined by Katja Kanzler as a way to analyze and describe those kinds of communication that potentially disparage those offended while transcending literary genres and styles (Kanzler 2021).

As argued below, the relevant source material must be seen within a broader framework of an invective mode of communication in the early Reformation. In order to explain this framework, the first section (2) lays out the prehistory of the mock procession and analyzes selected examples of visual, printed, handwritten, and oral communication in disputes concerning Franciscan preaching in Annaberg. It also reveals wider details concerning the context and the conflict process between 1520 and 1524 to include a critique of a too narrow print-and-polemics approach to the Reformation. The discussion then (3) lays out the case for a rather holistic approach and proceeds to elaborate on a broader framework for our source material by highlighting some features of the debate about the early Reformation public sphere. It introduces an analytical perspective that uses forms of invective communication in both printed and manuscript texts as a basis to investigate the dynamics and the interplay of different media while devoting specific attention to polemical comparisons (Brauner and Steckel 2019 with a broader view). The final section (4) builds on these reflections and re-contextualizes the Buchholz mock procession within a chain of local, regional, and media events in order to explain, first, why it took place in Buchholz at all. Second, through a brief description of the consequences and subsequent communications from two different perspectives, this section interrogates the importance and meaning of the mock procession in situ. Some of the material analyzed is new to Reformation Studies and will be discussed in some depth. The article concludes (5) with a short reflection on the role and character of invectives in the early Reformation.

Before outlining any further debates, it is necessary to outline both the specific spatial context of the relevant source material and the historiography on Reformation Buchholz and Annaberg. Both towns had been founded during the so-called ‘Great Mining Clamour’ (Großes Berggeschrey) in the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge) of southern Saxony in the late fifteenth century, when the discovery of new silver deposits stimulated the founding of new mining centers. Here, Annaberg rapidly grew into the second largest city in the whole Duchy of Saxony, with 8000 inhabitants in 1509—exceeded only by Leipzig—and its dynamic economic development was hardly interrupted even by one of the first major sixteenth-century outbreaks of the plague in 1521, which caused nearly 1200 deaths (Laube 1976, 30–37; Meltzer 1928, 321–22). Only very recently, in 1485, had the Wettin lands of Saxony been split in the so-called Partition of Leipzig. As a result, an official border divided the Ore Mountains, where the Ernestine and Albertine dynasties shared most of the rights concerning mining and sometimes shared sovereign rights as well, which caused additional trouble during the early Reformation, especially in nearby Schneeberg, seat of the shared Wettin mining administration.4 Annaberg, however, not merely continued to evolve as a mining center, but also soon became a symbolic locus of Duke Georg’s efforts at Catholic church reform. It was here that the Duke of Saxony, one of the most progressive and influential leaders of the Holy Roman Empire, fully implemented his Catholic ecclesio-political reform agenda (Volkmar 2008, 357–84). He not only founded a prominent Latin school and a Franciscan monastery, but also the biggest church in Saxony to date—the famous St Anne’s church. Moreover, he achieved a papal grant for biannual indulgences around Easter and the Feast of St John in the summertime, both of which were later flashpoints of public pro-Reformation critique and invective (Bünz 2017; Moeller 2004). The region around Annaberg witnessed unprecedented social and political upheaval around 1500 that included religious troubles, as when in 1501 the first city preacher, Johannes Pfennig, was unmasked as a convinced Hussite (Volkmar 2008, 460–61). For some time following, the consequences of the discovery of silver continued to be felt in both a huge wave of migrating workers and the founding of dozens of new mining towns. Migrants came, for instance, from Bohemia and Tyrol to what was one of the most vibrant and rapidly developing regions at the time. Thus, the dynamic transfer of people, goods, and ideas deeply shaped the region and its comparatively young urban landscape.

Plainly visible from Annaberg at a distance of only a few hundred meters, Buchholz had been a neighboring town since its foundation in 1501 with only 16 (!) owners of land and houses on ground belonging to the abbey of Grünhain. Only a small stream (the Sehma) marked the boundary between both towns. Buchholz was an Ernestine enclave, sharing borders with the Albertine Duchy of Saxony and the abbey of Grünhain. The purpose of this Ernestine foundation was simply to secure a share of the rich silver deposits, though it never grew as large as its Albertine rival and its expansion remained largely unplanned. Still in 1520, for instance, the town’s food supply was to a large extent dependent on Annaberg’s market (Laube 1976, 37). Despite their rivalry, there existed close social, economic, and religious ties between the two towns.5 These gave rise to an escalation of conflicts throughout the 1520s between the ducal officials in Annaberg and the Buchholz bailiff of the mines, Matthes Busch, something that was soon paralleled by each community’s prominent and divergent role over the course of the early Reformation. Busch not only cultivated contacts to Ernestine towns such as Zwickau, the biggest and most important trading town in the Electorate of Saxony and an early setting for Reformation conflict as well as a temporary hub for the spread of Reformation literature (Bräuer 1983; Karant-Nunn 1987; Stadtverwaltung Zwickau 2016).6 He also hosted guests who allegedly sympathized with the Wittenberg Reformation and travelled through the region, for instance from nearby Joachimsthal, a Bohemian mining city with a high ratio of Karlstadt sympathizers (Wolkan 1894). Hence in the eyes of Catholic Albertine officials, Buchholz was nothing more than a “pit full of heretics” (“spelunca haereticorum,” Richter 1756, s. fol.) that threatened the faithful in Annaberg. This reputation persisted: More than a century later, the famous chronicler Christian Meltzer, pastor in Buchholz between 1687 and 1733, reported the existence of names based on earlier epithets of heresy like “John the heretic” (“Kezer-Hannß”) or “Melchior the heretic” (“Kezer-Melchior”) (Meltzer 1928, 137).

The historiography of the early Reformation has dealt with religious quarrels and controversies in Annaberg, and to a lesser extent with the events in the neighboring town of Buchholz, since the nineteenth century. Despite the impressive work that has been done over the centuries, Reformation historiography has largely focused on two prominent sequences of events in the region which cast long shadows over other sources and contexts. Most of all, the above-mentioned printed reports on the mock procession of 1524 in Buchholz attracted persistent attention.7 Already in 1906, Alfred Götze called the Buchholz mock procession a grotesque misrepresentation, thus ‘travesty,’ that is, a means to expose these rituals’ true nature or identity, while criticizing a world already turned upside down (Götze 1906, 32). Götze’s interpretation, and later Robert Scribner’s well-known reading of the event as carnivalesque parody, still represent the state of the art, even though both remain controversial. In addition, a recent analysis of how Friedrich Myconius’s handwritten eyewitness account of the event was transformed into the first printed report on the procession revealed significant changes to the meaning of participants and requisites in the printed versions (Kästner and Schwerhoff 2021). Another prominent chain of events is also associated with Friedrich Myconius, a former Franciscan monk and later reformer in Gotha, who in early 1524 absconded from monastic imprisonment in Annaberg and subsequently published a pamphlet about his experiences there, in which he classified the local situation as a kind of early Lutheran martyrdom (Schlageter 2012, 138–49). He reappeared as a preacher in Buchholz only a few months later (summer 1524), where he not only attracted a huge audience of Annaberg’s inhabitants but also witnessed the mock procession.

Due to the fact that the two towns of Buchholz and Annaberg belonged to different Wettin Lordships, not only have manuscripts survived in different archives, principally Dresden and Weimar, but local historiographies were also divided along municipal borderlines given the centuries-long rivalry of both towns. The unique setting on the direct border between the Electorate and the Duchy of Saxony could be characterized as a kind of fault line between a minority of early pro-Lutheran critics and Catholic defenders of traditional rites and church doctrines, not to mention between incipient reformed confessions that would produce rifts within each town’s communities.8 Furthermore, manuscript survival is patchy within the municipal archives in Annaberg-Buchholz thanks to numerous losses from town fires. Among surviving sources are, on the one hand, those that have been partly brought to light either by local historians like Ernst Louis Bartsch or in editions of the official correspondence of both Wettin houses, albeit by and large only in footnotes (ABKG vol. 1, Bartsch 1897, 1899).9 On the other hand there are some famous libels that were incompletely transcribed by Annaberg teacher Oswald Bernhard Wolf in 1886. In 1993, Robert Scribner mentioned that Wolf’s transcriptions were faulty, incomplete, and in need of revision, though no one has followed Scribner’s suggestion so far (Scribner 1993, 156n17). As will be shown below, our imperfect knowledge of those libels is an issue that not only undermines Wolf’s work but also weakens more recent local studies that have partly misinterpreted these libels and also overlooked relevant sources that have survived in the Hauptstaatsarchiv in Dresden.10

Given these shortcomings, researchers have to date failed to write a history of these events from a micro-historical and regional historical studies perspective that takes into consideration the wider communicative context, in particular broad urban networks and the dynamics of the early Reformation public sphere. Nonetheless, there are some important studies that help to frame such an approach, principally Christoph Volkmar’s impressive study on Duke Georg’s ecclesiastical politics but also the landmark series of studies on the Reformation in Thuringia produced by a group of Jena researchers led by Werner Greiling and Uwe Schirmer; the work of both Volkmar and the Jena group encompasses the former Wettin lands.11 Finally, a recent, well-informed study written by Czech historian Jiři Černý has revealed the processes of networking across the Bohemian-Wettin borderlands as well as the region’s relations to important centers of printing, such as Wittenberg (Černý 2021). These studies, together with recent research on the Reformation public sphere, the market and economy of print, as well as oral and written communication, represent a starting point for taking a fresh look at both widely known and hitherto unknown sources.

2. Invective and the Reformation Public Sphere. Letters, Lampoons, and Pamphlets in Buchholz and Annaberg

As Thomas Kaufmann has recently pointed out, the predominance of printed sources in relevant and extant libraries of sixteenth-century nobles and scholars makes it difficult to follow the traces of readers (2019, 4), even though local and micro-historical studies have revealed much about the religious self-consciousness of the laity, for example (Craig 2016). Nonetheless, it remains extremely difficult to write a history of how common people might have read, adapted, and employed Reformation literature. In this context, the surviving sources from Buchholz and Annaberg are unique and offer an ideal opportunity to reconstruct the broader communicative context in this region and how polemical antitheses and invective language were prevalent in everyday communication. To lay the groundwork for a broader conceptual discussion, it is first necessary to explore some examples.

The years 1522 and 1523 marked a high point of anonymous critical letters, handwritten pasquinades, and libels in Annaberg, while in other mining towns like Schneeberg anti-monastic pasquinades were pinned to the church doors (Sommerfeldt 1921)—obviously not entirely coincidentally during a general boom of printed anti-fraternal Reformation critique (see below). As a consequence, authorities added supplementary regulations to the mining code (Bergordnung) in Annaberg on March 7, 1523 that were important beyond the city.12 The new ordinance, which was promulgated while Duke Georg stayed in Annaberg and should be viewed against the backdrop of negotiations at the diet of Nuremburg, specifically forbade the sharing or distribution not only of Reformation literature but also of handwritten pasquinades, libels, as well as of slanderous songs. The justification for this ban was an increasingly invective mode of communication (StA-D, 10024, Loc. 9827/22, fols. 152–163). While its broader context was Duke Georg’s general efforts to contain the spread of Reformation literature (including Martin Luther’s Septembertestament), local events were also important in framing this prohibition: Already in 1520 a public controversy between Wittenberg reformer Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt and Annaberg Franciscan guardian Franciscus Seyler had marked a first peak of religious dispute in the region. The whole affair had also made Duke Georg painfully aware of the dangers of prominent pro-Lutherans such as Karlstadt travelling incognito. Whatever his original intention or the circumstances of his journey—which remain obscure—Karlstadt stopped briefly in Annaberg in 1520, possibly while travelling home to Wittenberg from Joachimsthal. He served as his own biographer in his treatise on indulgence, where he mentioned his incognito presence in Annaberg.13 This reference alone was obviously intended as a scoffing remark against the Albertine magistrates and represented a scandal in the eyes of Duke Georg. Among a huge crowd of people from the town and its environs, Karlstadt attended a Franciscan sermon unrecognized by his enemies. During this sermon, the Franciscan guardian Franciscus Seyler and his deputy Johannes Forchheim, in their defense of indulgences, publicly denounced the Wittenberg theologians as the new and false prophets who would deceive the people, already a commonplace accusation since the late Middle Ages and now levelled by both sides of the reform debate (and an accusation that was revived again during the forthcoming inner-Reformation disputes). As Sita Steckel has convincingly shown, late medieval debates on heretics had already shaped and rigidified an enemy image that thrived on the idea of false piety and hypocrisy. While these debates diffused in different media and genres, correlating accusations could be detached from the original references and contexts. They could then be adapted and revived in other contexts and conflicts, as for instance in later Reformation disputes (Steckel 2012).

By 1520, Karlstadt had come to perceive any attacks against himself as life-threatening in a presentiment of the dangers to come from the Roman heresy trial (Bubenheimer 1977, 193–95; Zorzin 1990, 112). He was already preparing lengthier writings to make his position against the Roman church clear, beginning with his Which Books are Biblical (De canonicis scripturis libellus) of August 18, 1520 (Bubenheimer 1977, 163–77; Sider 1974, 86–103), and so, faced with the attack of the Annaberg Franciscans, he felt more than obliged to respond. He correspondingly informed his audience in print on August 10, 1520 and ‘leaked’ some compromising details of his private correspondence with Franciscus Seyler in the aftermath of the Annaberg sermon incident. No doubt, Karlstadt saw the common man as an active and discerning participant in the debate (Todt 2001, 133; Matheson 1998, 78). Obviously, Karlstadt was able neither to preach a counter-sermon in Annaberg nor to dispute in front of the urban public there. Thus, he sent a letter to Franciscus Seyler, who in his written response–of which Karlstadt made full use in his first anti-Seyler pamphlet–refused to enter into a discussion and denigrated Karlstadt as a bastard. By bringing this delicate information before the public, Karlstadt was able to discredit Seyler.14

In any event, this personal offence had an impact on Karlstadt, who made the insult and his feelings about it public. How much the conflict might have hurt Karlstadt or at least gave him the opportunity to play the injured party for effect becomes apparent in his second pamphlet against Seyler, On Consecrated Water and Salt (Von geweychtem wasser und salcz), published soon after (on August 15 1520). Here Karlstadt repeatedly informed his audience about the sermon incident, which in his view had triggered the whole dispute, even though he modified the story in a minor but crucial aspect: While Karlstadt again generally reflected on Seyler’s polemic from the pulpit, now Seyler was said to have insulted Karlstadt by name during the sermon and not only by referring to the new Wittenberg prophets as a heretical group (Bodenstein von Karlstadt 1520b, fol. Aii recto, 1520a, fol. Aii recto). Defending one’s honor was a core principle of early modern society and immediately also became an essential rule of the new public sphere, particularly in print. This might explain why otherwise busy theologians and university professors like Karlstadt were constantly involved in pamphlet wars, paradoxically feeding public demand for texts in a genre that they themselves deemed trivial (Matheson 1998, 61–62; critical remarks in Kaufmann 2019, 4–5). In this specific case, Karlstadt directly addressed Seyler more than 70 times in his first pamphlet, in contrast to the solitary mention before his audience. The whole text is a stylized conversation with Seyler in front of a reading and hearing public.

One of the crucial scenes in the text furthers Karlstadt’s aim to invert the original invective, by which Seyler had defamed him as a bastard. Here Karlstadt himself unmasks Seyler as a man who lacks intellectual wherewithal because he eschewed academic dispute in favor of socially unacceptable abuse. Comparison by implication here served to close the ranks of the author (Karlstadt) and his audience. The exposure of Seyler’s ‘true nature’ as a ham-fisted ropemaker (Ger. Seiler) substantiated Karlstadt’s point that Seyler did not deserve his position as a Franciscan superior. Also, such an approach mirrored a widespread rhetoric of disparaging through invective naming (Lobenstein-Reichmann 2013, 49–56). Karlstadt’s second pamphlet against Seyler concluded the previous discussion and was subtitled ‘against the undeserved guardian Franciscus Seyler’ (“wider den vnvordie(n)ten Gardian Franciscus Seyler”).

As German literary scholars and historians have shown, the new media universe of the Reformation multiplied the ways in which a text could be adapted (Toepfer 2010).15 The new attention economy of the Reformation, which became essential in view of the exploding numbers of prints, not only favored new ways of marketing and style but also of selective reception. In 1523 the storm clouds of the Karlstadt-Seyler controversy had anything but cleared away, both in printed debates and in local quarrels in Annaberg (see Peters 1994, 173–84). The author(s) of one anonymous libel, self-identified as “the crowd of the common men” (“tvrba herr omnes”), also attacked Franciscus Seyler as an undeserved guardian. The author(s) explicitly quoted Karlstadt and thus made unmistakably clear that Karlstadt’s critique was still present and his invectives against the Annaberg Franciscans remained relevant. The libel also insulted the Franciscan as a notorious “Tetzel brother” (“tetzel bruder”, meaning a monk who behaves like Johann Tetzel), already a vilifying comparative phrase that was prominent enough not to require glossing (StA-D, 10024, Loc. 9827/22, fols. 156 recto and 160 recto ). As we know from the history of pasquinades and libels and their reception, it was not especially important that consumers had a precise and detailed recollection of their contents. Rather, the problem for those who had been disparaged was, more often than not, that others were aware of the existence of those libels (in our case a printed pamphlet) and of catchphrases like “the undeserved guardian” (Rose 2020; Siegemund 2020, 2022). This reinforces Anja Lobenstein-Reichmann’s findings concerning the relevance and the range of invective through naming and keywords (Lobenstein-Reichmann 2013, 48–70).

The Karlstadt-Seyler controversy is telling for the situation in Annaberg. Since Duke Georg had committed himself to a strict anti-Lutheran policy, pro-Reformation impulses and critique came from the outside rather than within Annaberg’s community. What in the following years also appeared elsewhere as one of the core aims of reform in urban communities—the preaching of the Gospel according to the Scriptures—was also claimed here to a significant extent by persons who had close relations to Annaberg but did not live there. This also applies to those lampoons of the 1520s whose authors identified themselves as strangers, and which cannot simply be ignored as mere disguise, as Oswald Bernhard Wolf suggested (Wolf 1886, 6). Relations were particularly close between the towns in the region, even if one considers only economic connections such as shares in the mining industry or other dependencies. Furthermore, as Jiři Černý has shown, religious networks throughout the Ore Mountain border regions reached as far as to the printing centers of Leipzig and Wittenberg (Černý 2021), something embodied in the person of Karlstadt. His close connections to Joachimsthal, where he preached in September 1522, are as well-known as his 1521 correspondence with Annaberg’s town clerk Anton Beuther. For example, Karlstadt dedicated his Explanation of 1 Corinthians 10 of December 1521 to Beuther, whom Duke Georg suspected, along with a couple of other townspeople, to be clandestine Lutherans.16 But as we have already seen, ‘heretics’ were also present among Annaberg’s inhabitants, though the evidence is sparse. Johannes Sylvius Egranus was another prominent pastor preaching in Joachimsthal who had not only preached against indulgences and criticized the abuses of monasticism early on, but who was also involved in the new printing business, for instance publishing (with Stöckel in Leipzig) a treatise on confession in 1522 (Černý 2021, 117–47).

Regional contexts were also decisive in other cases. In 1523 an anonymous critic insulted the Franciscan preacher in Annaberg as “a Freiberg son of a cow” (“freibergischer kwe Sohn”) (StA-D, 10024, Loc. 9827/22, fol. 152b recto). The critic thereby not only referred to rumors about the miraculous sign of a malformed calf, born on December 8, 1522 in Waltersdorf near Freiberg, another Saxon mining town, but also demonstrated his knowledge of those illustrated pamphlets that made the Freiberg ‘monk calf’ famous, in particular Luther and Melanchton’s jointly written mock exegesis The Meaning of Two Horrific Figures, the Papal Ass at Rome and the Monk Calf Found at Freiberg in Meissen (Deuttung der czwo grewlichen Figuren, Bapstesels czu Rom und Munchkalbs zu Freijberg ijnn Meijsszen funden), published in early 1523.17 The anonymous piece of invective in Annaberg is indeed remarkable because it demonstrates the existence of local public debate about Luther’s interpretation of the monk calf as symbolizing the deficiencies of the Roman church and monasticism.

In the eyes of the critic, the Franciscan preacher had given occasion to yet another bovine conclusion (“kwysch conclusio”) in one of his sermons.18 The Franciscan had allegedly preached that God commits a wrong by condemning those sinners who could do nothing but sin or were even compelled to sin (like Pharaoh in Exodus, whose mind had been confused by God). Unfortunately, we do not know the exact words of the sermon, so that we cannot know whether the critic might have misunderstood the preacher’s point. Presumably, the preacher in his sermon had already reacted to Luther’s interpretation of the monk calf. The Wittenberg reformer had stated that the father confessors and monks were as obdurate against the words of the Gospel as otters when they close their ears under water. Moreover, clerics and monks, according to Luther, could not escape God’s judgement like the obdurate Pharaoh because they just close their eyes and do not want to see and recognize the miraculous signs sent by God, intended to move people to repentance such as the monk calf (Luther 1523, 381).19 In any event, the reaction to the sermon was exceptional, for the critic admonished the Franciscan preacher both with insults and by quoting, albeit incorrectly, Acts 7:51–2 after the text of the Latin Vulgate. The critic used Scripture to underline Luther’s point in his interpretation of the monk calf, namely that monks were obdurate, that they resisted the Holy Spirit, and that they were false preachers who did not understand the truth of the Gospel.

Another unknown visitor, most likely from Joachimsthal, came to Buchholz and Annaberg in either late 1522 or early 1523 and left behind another one of those sources of concern for Duke Georg and his local magistrates. In an undated letter sent to Franciscus Seyler, he complained about yet another Franciscan sermon.20 The letter was apparently written while the author was a guest of Matthes Busch in Buchholz and it clearly represents one of those infamous texts forbidden by the censorship regulations of 1523. It was common to make notes from sermons and for visitors in Buchholz it also seemed to be common to attend mass in Annaberg, given the unfinished state of Buchholz’s St Katharinen church and its increasingly inhibited pastor, Andreas Wilde, who had neither strength nor will to preach either for or against the Reformation.

The anonymous letter was overlooked by Oswald Bernhard Wolf in his first edition of the Annaberg lampoons and has not been previously studied. Its author not only reformulated the (in their eyes) objectionable Franciscan sermon in eleven numbered sections, as was conventional in printed sermons and treatises, but also referred explicitly to biblical sources and paraphrased ongoing debates and texts by Luther to contest the Franciscan doctrines. In this way the anonymous letter also illustrates the situation alongside the border between the Electorate of Saxony and the Duchy of Saxony, which heated up during the 1520s. While Duke Georg vigorously tried to enforce the Edict of Worms, reforming activities spread and caused serious trouble, such as a rash of runaway monks crossing the shared border. Hence, in their public sermons, preachers increasingly came to a point where they would preach not merely to explain pericopes and inform about doctrines and traditions, but were rather obliged to reject the challenge of the Reformation, that is the new doctrine of justification and its implications of denigration of the traditional order of the church on the one hand and, on the other, competing preachers.21 This evidently happened in Annaberg, where the anonymous correspondent saw himself confronted with an offensive sermon that referred back to Seyler insulting Karlstadt as a ‘bastard’ in 1520.

In his sermon, the unidentified Franciscan preacher (probably the vice guardian Johannes Forchheim) had made a point about the reformed claim of scriptural proof, in particular concerning the question of whether matrimony was based on biblical norms. The discussion by the anonymous author reveals how the preacher must have argued in the first place: on the one hand defending the principles of monastic life and, on the other, questioning the idea of marriage as a universal divine institution, an essential concept of Luther’s thought (Witt 2017, 11–34, 172–205). Accordingly, the anonymous critic defended matrimony and lambasted the monastic vow of chastity as based on false human teachings. The argument relied on the Reformation critique of monastic vows and human teachings, which Luther had for instance taken apart in his 1522 treatises On monastic vows (De votis monastici, 1522a, translated from Latin into German by Justus Jonas) and Of human doctrine and how to avoid it (Von Menschenlehre zu meiden, 1522c).

As the Franciscan preacher based his sermon on the question of how to legitimately interpret the Gospel, he also pinpointed the central term of early urban Reformation—the true Gospel (Blickle 1987, 90–96, 101–8). He could simply have disputed Lutheran claims dispassionately and with reference to relevant aspects of Catholic doctrine, but emotions and invectives already played a part. Since, as the preacher made abundantly clear, matrimony could not be considered as a divine institution based on the Bible, people “remain vain children of whores” (“Eytel Huren kinder vnd pleybens”; StA-D, 10024, Loc. 9827/22, fol. 152 recto). As we would expect from the Karlstadt-Seyler controversy, such abusive wording could not be left unchallenged, even though the preacher had obviously not intended to insult his audience. The anonymous critic wrote in the exordium of his letter that he found the Franciscan was not preaching the pure word of God, which he had wanted to hear. As an apparently already convinced Lutheran and reader of Lutheran texts, the critic therefore jumped at the chance to contradict the preacher through his letter,22 the contents of which we may suppose spread to well-informed circles in the region via the Buchholz bailiff Matthes Busch, who played an important role as a source of news for almost all relevant authorities between Buchholz and the Ernestine residences in Wittenberg and Weimar.

The issue of matrimony was a subject of controversial public discussion elsewhere but it was particularly prominent in the Saxon Erzgebirge. Some authors, like former Franciscan Eberlin von Günzburg, who became a notable figure in the 1523 anti-Franciscan pamphlet campaign, showed themselves outraged over the monastic vow of chastity, which in their eyes threatened good public order (Eberlin von Günzburg 1522, fols. b–biii; see Dipple 1998). Luther also published a sermon on The Estate of Marriage, a text that resulted from a visitation journey in 1522 during which he had preached on this subject, for instance in Zwickau. In 1522 Karlstadt had also preached in Joachimsthal, and the surviving records of his sermon mirror the anonymous critique from Annaberg in many ways, for example in his critique on the cult of saints that had been introduced by the new Pharisees as well as on false human teachings by false prophets (Hasse 1990). At the juncture of the two Saxon territories such issues were a matter of debate, as the seeming geographical fringe took center stage.

In his anonymous letter the anti-Franciscan critic rejected the accusation of being a son of a whore both from its social implications and from a theological point of view. He referred to the concept of a Christian congregation (“Christliche Vorsamlung”), a social ideal that the Franciscan preacher had supposedly denigrated in his sermon (see Eph 5:23-27). Luther had famously outlined this term in his On the Papacy in Rome Against the Most Celebrated Romanist in Leipzig (Von dem Papstthum zu Rom wider den hochberühmten Romanisten zu Leipzig, 1520). One can safely assume here that such a reference was not made entirely coincidentally by the anonymous critic. He also explicitly cited Luther’s papacy treatise and vituperated the “holy men” (“heyligen leutte”, ironically used to mean hypocrites). He mocked monks as adulterers and sons of whores and even as descendants of the “red Whore of Babylon” (“der babilonischer rotten Hurren”), a phrase coined by Luther in On the Papacy (1522a, 322; Kaufmann 2014, 21).23

The Franciscan preacher, in his attempt to defend the monastic lifestyle, must have tried to prove the superiority of his order by referring to the legend of St Francis. The cult of saints was also another matter of acrimonious debate during the Reformation, but the anonymous critic did not bother to discuss this issue at length. Instead, he simply called the legend of St Francis a “lie-gend” (“lugende”), quite some years before Luther, in his famous rejection of the legend of St John Chrysostom, popularized this term.24 Both made this reference through wordplay with the German terms Legende (legend) and Lügende (meaning an invented story; from lügen, to lie). Remarkably, this neologism must have already been common to a certain extent at the time, for the critic did not deem any gloss necessary for this rhetorical wordplay. In any case, the cult of saints remained controversial in the public debate alongside the Saxon border because the veneration of a homegrown Saxon saint—St Benno of Meißen—had long since been of central importance for Duke Georg’s ecclesio-political ambitions (Finucane 2011, 207–40; Volkmar 2002, 2006, 2017). Unsurprisingly, the debate about St Benno gave cause for renewed and ungracious invectives from both sides when some Buchholz townsmen acted as principal characters in a local dramatic performance in 1524. But before examining these events in detail, it is necessary—as stated at the outset of the present section—to situate the previous examples within a larger framework and draw some conceptual lessons.

Having scrutinized and recontextualized its various sources, the case of Buchholz and Annaberg helps us to shed some light on the history of communication with the archetypal ‘common reader’ during the early Reformation and thus on the dynamics and the interplay of different media within the early Reformation public sphere. In addition, the case features that characteristic of sixteenth-century public communication that has recently been described as invective (Beckert et al. 2021; Dröse 2021b; Münkler 2021). The viewpoint represented here has been inspired by the work of the Collaborative Research Center 1285 (based at the Technical University of Dresden) and its concept of ‘invectivity.’ The scholarship emerging from this Center, historical as well as literary, has used this concept to broaden perspectives on the ‘polemical’ and to analyze and describe the dynamics of the early Reformation public sphere (see below).

Church historians and theologians have characterized the early Reformation as a “laboratory of possibilities” (“Laboratorium der Möglichkeiten,” Kaufmann 2018, 67:20) and an “imaginative world” (Matheson 1998) of deeply transient mental images of belief and of sometimes even playful controversy (such as in Reformation dialogues as genre or in the hidden humor and parodies of pictorial art) (Matheson 1998, 1–26).25 Needless to say, such characterizations do not mean that everybody could do, say, or write anything at any time. Playfulness came to a close every time it was confronted with mutual distrust, prohibition, censorship, and threats of imminent prosecution, even to artists.26 The Edict of Worms drew the line very early, although it should be remembered that its enforcement remained controversial and lasted for years, as was also the case in Buchholz and Annaberg.27

Ultimately the history of the early Reformation public sphere is inextricably wedded to the introduction of the printing press, which constituted a necessary prerequisite for the creation of both a dense web of public opinion and the perseverance of the Reformation. Bernd Hamm has underlined that the effects and the impact of the ‘new’ media in print, above all of illustrated broadsheets and pamphlets, were not domesticated during the first years of the Reformation (1996, 153). While not a new technology itself (Eisermann 2011; Griese 2015), the printing press accelerated the dissemination of knowledge and the exchange of ideas at an unprecedented speed and scale. Nevertheless, a common culture of oral face-to-face communication still predominated, a fact that historians have emphasized for decades (among others, Fox 2000; Schlögl 2014). Accordingly, preaching remained an important medium in the Reformation. Without charismatic preachers and powerfully eloquent sermons, the success of the Reformation cannot be explained.28 And the above examples clearly demonstrate that anti-Reformation preaching cannot be ignored. Oral culture also significantly shaped the textual form of printed pamphlets, which echoed as well as stylized oral communication and vice versa. Scholars have analyzed these echoes as forms of conceptual orality and conceptual scripturality, respectively.29 What Rainer Wohlfeil and others have called the Reformation public sphere is thus defined by a complex and polyvocal interplay of different media.30 Furthermore, the growing complexity of early Reformation mediality also multiplied possibilities to adopt thoughts and arguments.31 As Susanne Schuster has argued, printed dialogues can be understood as, for example, a continuation of academic disputations by vernacular literary means (Schuster 2019). However, as the surviving lampoons and letters from Buchholz and Annaberg clearly prove, such stylized dialogues did not necessarily match reality. This was, first of all, because they hid power structures and the means of persecuting alleged heretics, while they also opened a space for conversations from a perspective in which the pressing questions of the time were negotiated as a problem of intellectual capacity. But power, authority, and control mattered, so anonymous writings—and (as outlined below) a different social and spatial setting for discussion in taverns and alehouses—were the medium of a different kind of dialogue, one that lacked any option for spontaneous immediate rejoinder.

Some other characteristics of the early Reformation public sphere are also noteworthy. First, the soon prevalent use of the vernacular in printed debates, which touched on broader social issues. Using the vernacular not only created the potential to involve the so-called ‘common man’ in public discourse but also elevated this to a norm by raising expectations that authors would seek to proactively address the ‘common man,’ albeit occasionally in a rather symbolic way. Such an aspiration became ever more ambivalent for systemic reasons. As literary scholar Albrecht Dröse has pointed out, vernacular pamphlets promoted the escalatory dynamics of invective in two ways: on the one hand, they “suspended the usual conditions for access to discourse” (Dröse 2021a, 56n116), which apparently became an even more problematic point when the Peasants’ War broke out in 1524 and Luther and other Reformation authors were blamed for causing turmoil and insurgency (Edwards 1994, 149–62, 1990). On the other hand, they operated in an invective mode that demanded reaction and facilitated follow-up communication, not least because interaction and interactivity are essential preconditions of invective communication, in which the roles of those who are disparaged, of those who disparage, and of a heterogenous audience which fulfills various functions to provide a chance of taking sides, can change dynamically.32 These arguments are closely linked to other points.

Second, confrontation and controversy intensified the pressure to position oneself and to make a decision in matters of religion, even though the basis for such decisions was not entirely clear and contradictions and ambiguities were the norm (Pohlig 2018, 329; see Posset 2014 as a case study). In a still pre-confessional era, the clash of sectarian views over the correct interpretation of the Gospel as well as over questions concerning the doctrine of justification was entangled more often than not with complex local political and social conflicts. At the same time clear lines between those who in one way or another remained loyal to the traditions of the Catholic church and those who would soon be labelled the ‘new Hussites,’33 later to become ‘Lutherans,’ were yet to be drawn. As a matter of fact, the term Lutheran (lutherisch) itself was originally coined to denigrate a deviant Other from an orthodox point of view, based on a heresiological tradition that named supporters after their supposed heresiarch (Volkmar 2008, 460–86). Both heresiology and church criticism, quite often in the form of satire, drew upon older traditions of antitheses and binary typologies.34 Correspondingly, personalized images were dramatized and used to sharpen critical points instead of carefully analyzing structural issues of belief and church organization (Matheson 1998, 123). Already by 1520, Luther portrayed the Pope as Antichrist and the Red Whore of Babylon (Revelation 17:4), a polemical comparison and extremity that left little room for further escalation in reference to typological comparisons. And as is clear from the above, it was exactly such invectives that encouraged selective reception.

As a consequence, finally, the abundant flow of invective shaped another aspect of the Reformation public sphere. Harsh rhetoric and coarse language, both of which could potentially disparage and humiliate one’s opponents, now found their way into print and into everyday debate. Invective rhetoric could be spread and ‘cultivated’ to a hitherto unknown and considerable extent. The reason lies within the very nature of both the Reformation’s appeal and its explosive power, which was to lay bare the rifts of the existing Christian world and to challenge its order and hierarchy (Oberman 1987, 203). Again, Luther was a role model.35 The milestones of polemic controversies in Luther’s biography are widely known, as is his use of public opinion for the purpose of self-justification. His media presence ensured his triumph.36 Luther’s sometimes harsh polemics were, as Kaufmann has put it, “a fundamental aspect of Luther’s makeup” (2017, 112), and they were as exceptional in many ways as the Wittenberg reformer himself.37 Luther played a pivotal role when he took up the sword of polemic and directed it at his opponents in sharp-tongued diatribes. His position, however, was one of confidence and self-assurance (Matheson 1998, especially 134). His aim was to articulate his thoughts and positions unambiguously while defending the truth of the gospel and his dedication to the ‘doctrina Christi’ (see Kaufmann 2017; see also Vind 2013, 6).38

3. The Buchholz Mock Procession in Context

Research into Reformation language and rhetoric has shown more than once that polemic in particular served as a means to sharpen thoughts and ideas, concerning both those under attack and those being defended.39 In a situation of fundamental confrontation, in which controversy fostered a “metaphysical dualism” (“metaphysischer Dualismus”, Schwitalla 2010, 117) between good and evil, drastic binary contrasts were omnipresent, helping to shape and reflect the eschatological worldview of contemporaries. The contrast between divine truth and evil heresy could easily be applied to any contentious issue. In addition, as for instance Lee Palmer Wandel has highlighted, throughout the Reformation period polemic “constructed simple bipolarities […], constructed two kinds of human being—true and false Christians,” for polemic does not tolerate any “grey zone” but claims “stark oppositions” and division (Wandel 2011, 134–40). When people were “condemned as groups,” as Heiko Oberman has emphasized, “individual differentiation becomes impossible. The individual human being disappears behind a uniform foisted upon him” (Oberman 1987, 242). To return to the characteristics of the Reformation public, the controversies of the time evidently cultivated a use of invective language, which in turn pointed to the basic polarizations of a conflict that went far beyond merely theological debates. Invective rhetoric pervaded public discourse and set rhetorical points of no return.

Though not a contemporary term itself, scholarship on the Reformation almost uniformly uses ‘polemic’ to describe the weaponized language of the sixteenth century, in particular with regard to fierce verbal attacks against individuals or to sharp-tongued controversies about irreconcilable doctrinal differences. Gerd Schwerhoff even speaks of “reformation hate speech” (Schwerhoff 2017). It is striking, though, that more often than not polemic itself is not defined in these studies (but see Lundström 2015, 7–8), whereas its use presupposes an understanding of polemic as an umbrella term “to describe any form of controversy,” as Sita Steckel has clearly pointed out in a thoughtful discussion of different research strands and traditions (Steckel 2018, 3).40 The broad use of polemic in Reformation research corresponds to the fact that polemic is a polyvalent term that is not only associated with a wide range of disputational practices but also oscillates between genre, language, and style.41

Other research fields use polemic in another sense “to denote disparagement or aggressive, degrading speech,” vilification, or shaming (Steckel 2018, 9), against which the Dresden Center has argued in favor of the term ‘invective’ instead. This choice is more than mere preference, for the varying definitions of ‘polemic’ make it a difficult term to use in interdisciplinary contexts. As a result, the abstract neologism ‘invectivity’ was coined to fix attention on communicative contexts and settings as well as on social dynamics and the effects of invective on social, political and cultural change, even though it has its roots in ancient, medieval, and humanist rhetoric.42 It understands invectives as always ‘in the making,’ as a matter of interaction and serial communication and not necessarily bound to individual intentions.

Nevertheless, given the prominence and importance of ‘polemic’ in Reformation scholarship, the case will not be argued here for simply replacing ‘polemic’ with a new term, for instance ‘invectivity,’ least of all for instances where the focus of inquiry is on the use of polemical comparisons, as in this volume.43 Instead, two arguments frame the use of ‘polemic’ here. First, the undifferentiated use of ‘polemic’ and/or ‘polemical’ in the literature sometimes blurs the line with other uses of language, visualizations, or actions that could potentially disparage or derogate opponents.44 Obviously, any differentiation that is necessary and useful must also not be obscured by the term ‘invective’, and is to be specified in terms of genre, form of language, and language experience.

The example of the Buchholz mock procession underlines the limits of the term ‘polemic’ to describe the performative reality as well as the textual representation of certain events. In fact, this mock procession was an expression of coarse humor, with its stylized laughter serving as an invitation to participate. It was also simultaneously a caricature, a parody, a satire, and—particularly in its printed versions—a polemic. It was also a media event, featuring different forms of representation in different media and textual forms, thus drawing a more complex picture of its invective quality, namely its potential to disparage. When we combine the concept of ‘invectivity’ with the common use of ‘polemic’ in Reformation scholarship, we are able to relate polemic to other forms of disparagement through a broader view on the invective mode of communication while still acknowledging that polemic played a pivotal and pervasive role.

The second argument refers to the relation of polemic, invective, critique, and propaganda or, as Andrew Pettegree has put it, the “culture of persuasion” (Pettegree 2005). Propaganda figured as a prominent concept in Reformation history since Robert Scribner’s For the Sake of Simple Folk. In his study, Scribner highlighted the use and importance of images not only to engage people of various levels of literacy with the Reformation message but also to initiate action. These aims were fulfilled by means of predominantly negative images and drastically personalized contrasts; the images studied by Scribner clearly marked climactic and less subtle scenes of visual polemic (Scribner 1981; Dröse 2021a; Münkler 2021). By contrast, Kaufmann has argued that it was not Luther’s polemics—to return again to this role model—that were deemed problematic by his contemporary opponents but rather the substance of his teachings and his claims (2017, 112). Considered from a perspective on the use of polemical language alone, such a finding might seem confusing, at least if one accepts an antecedent distinction between critique and invective. But such a distinction fits ill with reality, as has recently been set out very clearly for the equally critical and invective potentialities of early modern pasquinades and libels (Schwerhoff 2021). While polemic is widely understood as a purported offensive mode of writing and speaking in a conflict,45 other forms of critical or factual statements—especially if expressed in a trenchant manner—can also feature an invective quality that will often only become visible in reactions to it. In addition, this can also include disputes about the very rules of controversy at what might be deemed a meta-discursive level.46

Furthermore, invective rhetoric served many different purposes. For instance, in learned Latin tracts and disputes among humanist authors it served to reassure the recipient of a letter or a treatise of the author’s own intellectual status and of a capacity to conform to the rules of elegant verbal jousting (see the studies in Baumann, Becker, and Laureys 2015; Israel 2019). As such, Reformation literature could be more or less polemical in style and inflection, but given the basic antagonisms, contradictions, and conflicts of the time it could, perhaps, hardly be non-invective. Every attempt to take up a position in the struggle for religion was likely to be interpreted as a disparagement and denigration of a different position, and some genres, like polemic pamphlets (Streitschriften), promoted it more than others. This becomes evident, for instance, in (printed) pastoral sermons, which Bernd Moeller and Karl Stackmann have characterized as “combat pamphlets” (“Kampfschriften,” Moeller and Stackmann 1996, 220:301–4, quote 301).

Among others, Peter Matheson’s pithy analysis of Reformation language informs us that form should not be divorced from content when analyzing the use of words.47 Moreover, form and content need to be contextualized against the backdrop of specific configurations of social, economic, judicial, and media conditions to analyze their functions and resonances as part of an ongoing discourse (Bellingradt and Rospocher 2019, 12; and Bellingradt 2011, 23). Only then are we able to analyze the dynamics of (public) communication that were essential to the Reformation as a process (Moeller 2001, 74; case studies now in Hrachovec et al. 2021). From a local perspective, the series of lampoons and letters from Buchholz and Annaberg, while blurring the line between otherwise well-defined genres, nevertheless provide exactly the kind of missing link between a broader public market for print, semi-public correspondence like official reports, and private or ill-defined forms of communication (such as, respectively, clandestine sermon notes and rumors) that help to describe processes of communication in the Reformation public sphere.

Furthermore, the linguistic concept of mode provides a helpful and complementary perspective. It refers to a diverse and dynamic cultural ‘procedure’ that relies on established language repertoires and cultural archives, for example discursive traditions and patterns of everyday language. It also ties itself to different genres and media, affects a wide range of communication and brings forth a vaulting modality of interaction and communication. This has been further refined as a specific concept of ‘invective mode’ that Katja Kanzler, in her discussion of popular media culture, has convincingly argued helps us to better understand and describe the “more generalized, more flexible and mobile, less formally bound principles” of communication, which transcend the boundaries of specific genres (2021, 30). As such it can be connected to the idea of the Reformation public sphere as outlined above, in particular to the interplay of different media and forms of communication. From this point of view, we do not need to decide, for instance, whether pamphlets or bound books were essential for the print market (for a well-informed holistic approach, see Kaufmann 2019) or whether specific genres like Latin polemics, vernacular sermons, dialogues, or visual images defined public discourse. Instead, the concept of invective mode allows us to see the pervasive use of invective, on the one hand, while on the other enabling us to recognize that invective might only “be present in textual artifacts to a gradable extent, i.e., more or less prominently” (Kanzler 2021, 30). As linguistic studies have shown, different modes can cohabit and interact in texts, which points to the correlation of critique and invective (and also of polemic) outlined above.48

Such a rather holistic approach forces us to consider Reformation communication as a process involving an entangled media landscape and thus to move beyond methods that exclusively privilege printed narratives (Emich 2008). It should have become evident that the specific circumstances in the border zone between Buchholz and Annaberg, with its atmosphere of mutual distrust, not only boosted religious conflicts but also created a situation in which an external trigger could easily provoke a parodic parade to mock the sanctified Bishop Benno. What was this trigger and did invective play a role in it? And what consequences, if any, did the mock procession have in the local context?

The first step in answering these questions in a final section is to clarify the timing of the event, which is by no means straightforward. In his remarkable early study on the veneration of St Benno, Christoph Volkmar has addressed this issue, concluding that it occurred at some point between July 15 and August 15, 1524. On July 14, one of two known eyewitnesses, Friedrich Myconius, wrote a letter to Stephan Roth in Wittenberg but failed to mention anything about the mock procession while discussing religious matters in Buchholz. On August 15, Myconius left Buchholz to take up a new position in Gotha (Volkmar 2002, 174–5; Bartsch 1899, 205–6). It is important to note that Myconius’ handwritten account of the procession meets the criteria for an open missive that must have circulated among a network in the region; otherwise, neither the only surviving transcript, reproduced in renowned chronicler Petrus Albinus’ collection of notes for a history of Schneeberg, nor its transmission to Wittenberg can be plausibly explained.49

Surprisingly, no Annaberg official seems to have taken any notice of the event, even though they reported a whole series of other occurrences to Duke Georg, who then repeatedly complained about several outrageous incidents, also in Buchholz (ABKG vol. 1, no. 744). The other eyewitness (at least of the final episode of the mock procession), Matthes Busch, remained entirely silent, most probably because he did not want to be held responsible for such disturbance of the public order by his Ernestine masters. This becomes even more striking when compared to his otherwise incredibly detailed reports or news (newe zeytungen) that shed valuable light on occurrences in the region and bear witness to a kind of intelligence network also in Annaberg. This network sometimes informed Busch even about the most private matters, which he zealously reported to his Ernestine masters. Even though his role in ending the mock procession was later highlighted in the printed versions, he neither mentioned nor even hinted at the event in any way.

Beyond providing a whole range of details about the transmission of Myconius’ report and its creative modification in print,50 research to date has ignored an important lead provided by Petrus Albinus. In a short note, Albinus referred to the mock procession and indirectly dated it as occurring between July 4 and 17, 1524. Although he was no contemporary, he probably had good reasons for choosing this window. In an earlier chronicle for the city of Zwickau, Albinus relied on the since lost notes of contemporary Paul Greff, a local churchman. In his reference to the procession, Albinus explicitly cited the transcript of the Myconius report that he inserted in his Schneeberg collection.51 It seems safe to assume that the Myconius report originally came from a bundle of sources collected by Greff: Albinus also provably inserted another document from Greff’s dossier that matches the noticeable paper size, a specific type of pagination within Albinus’ notes is apparent only in these two documents, and it has a strikingly similar typeface.52 Combined with the possible window suggested by Volkmar, the mock procession thus likely took place either on July 15 or 16, 1524, more likely on July 16 given its symbolic meaning in reference to June 16, the day of St Benno’s elevation.

Other manuscripts provide further evidence that helps us to understand why the procession took place. One shrewd author, probably writing in July 1524, lampooned the Annaberg preachers in a highly individual manner. He used an original letter of indulgence, which had initially been sold in Annaberg on July 10, 1510 (during Tetzel’s campaign there) but was now satirically re-granted to ten unnamed prostitutes in Annaberg. Moreover, the unknown taunter added some invective pieces of poetry, saying, for instance, that Roman grace and indulgence would be given to the new false god, Bishop Benno, in order to comfort him because the old God did not want to sell indulgences anymore (StA-D, 10024, Loc. 9827/22, fol. 163). This remarkable document hints at a specific preacher who embodies the missing link between the events in Meißen, Annaberg, and Buchholz. The unknown author explained very plainly for whose benefit the indulgence was sold in Annaberg: “so that the ‘potzer’ is able to keep beautiful women” (“das der potzer auch mocht schone frauen ausz halden(n)”), thus reviling him as a fornicator. The anonymous author directly offended a specific person whose name he facetiously misappropriated. The name Potzer referred to the ‘bogeyman’ (Ger. Butzemann), clearly insulting the Dominican Nikolaus Poetscher (thus ‘potzer’), who had been appointed as preacher to Annaberg in early July in order to replace the deviant preacher Johann Bindmann, who had been arrested and was later expelled to Joachimsthal. According to the well-informed Matthes Busch, Poetscher had served in Meißen earlier, where he must have witnessed the elevation ceremony for St Benno on June 16, 1524, which had been preceded by the promulgation of a plenary indulgence.53

As early as July 5, 1524, Busch reported to Ernestine Duke Johann the Elder that it was with “sneaky, flattering, and weeping words [that Poetscher] tries to seduce the chosen ones“ (“schleichenden schmeicheln, weinenden wort(en), vnd möcht wol, dy aus Erwelt(en) vo(r)fhuren“), as Busch repeatedly labelled the Buchholz community and the ‘true’ Christians among Annaberg’s citizens (ThHstA Weimar, EGA, Reg. Ll 54, fol. 12 recto). As shown below, Busch’s characterization of Poetscher’s sermons, one of which he received in full transcription,54 most likely stemmed from a familiar informer from Annaberg—in another report he speaks of an informer as a ‘good guy’ (“guth gesell”; ThHstA Weimar, EGA, Reg. Ll 54, fol. 14 verso)—because the same phrases reappeared in mid-August 1524 in another remarkable lampoon against Poetscher and seem to have represented quite common accusations against him (ThHstA Weimar, EGA, Reg. Ll 54, fol. 12 recto).

It was the same Poetscher, then, who repeatedly not only preached in favor of indulgence but also railed from the pulpit against the Buchholz community. Unfortunately, we only have evidence of the exact wording used from late July and early August 1524, but according to Matthes Busch we can be sure that Poetscher played the same role from the beginning in order to defend the principles of Catholic faith and above all to strengthen the faith in the saints and in the offer of indulgence. The situation was far from easy for Poetscher, who faced huge challenges. During the summer of 1524, the abovementioned Myconius was appointed as preacher in Buchholz. A former Franciscan monk, Myconius had himself gone through a long and sometimes poignant journey of conflict and disparagement, which he partially recounted in his printed stylized consolatory letter to the inhabitants of Annaberg shortly before the events of 1524 (on Mykonius now Gehrt and Paasch 2020; still relevant Scherffig 1909). He might have addressed it to a clandestine Annaberg Lutheran community in particular, but by and large the pamphlet was a symbol of personal liberation (Schlageter 2012, 138–49). Myconius escaped from his monastic imprisonment in Annaberg on Palm Sunday 1524 and Matthes Busch, in Buchholz, helped him get to Zwickau undetected.55 From there he returned to Buchholz at a time when its community was in desperate need of a new preacher and turmoil spread throughout Annaberg, resulting from the arrest of former preacher Bindmann and the new preacher Poetscher offensively promoting indulgences prior to the Annaberg indulgence around the Feast of St John. This situation caused new unrest among the town’s inhabitants, who not only reacted by means of new pasquinades against the preacher but also against their persecution by ducal officials. In the hundreds, they even went to listen to Myconius preaching in Buchholz (ABKG I, No. 692).

In return, the Annaberg preachers severely attacked the Buchholzers as heretics in their sermons while reports about the veneration of St Benno were spreading, accompanied by Luther’s ferocious attacks against it and awareness that an already controversial preacher in Annaberg had taken part in the events in Meißen. Thus, as I would argue, what could have been a better option for those Buchholz dwellers who felt offended than to mock their opponents by exposing them to the ‘laughter of heretics,’ as Anselm Schubert has put it, via a kind of carnivalesque expression and performance that had already been tested as a sort of stylized quasi-ritual in Wittenberg in December 1520 (Schubert 2011)?

What actually happened? On a summer day in mid-July 1524, a crowd of young men formed a mock procession to elevate the ‘holy’ bones of some animals. In his eyewitness report, Myconius distanced himself somewhat from these men by calling them “a rabble” (“gepobels”). Using the printed version, Scribner has summarized the whole scene as follows:

A mock procession was formed, with banners made of rags, and some of the participants wearing sieves and bathing caps in parody of canons’ berets. They carried gaming boards for songbooks56 and sang aloud from them. There was a mock bishop dressed in a straw cloak, with a fish basket for a mitre. A filthy cloth served him as a canopy, an old fish kettle was used for a holy water vessel, and dung forks for candles. This procession went out to an old mine shaft, preceded by a fiddler and a lautist. There the relics were raised with an old grain measure and placed on a dung carrier, where they were covered with old bits of fur and dung. A horse’s head, the jawbone of a cow and two horse legs served as relics, and were carried back to the marketplace. There the bishop delivered a mock sermon and proclaimed the relics with the words: »Good worshippers, see here is the holy arse-bone of that dear canon of Meissen St. Benno«—holding up the jaw-bone. Much water was poured over the relic to »purify« it […]. Then the figure of the pope was taken up on the dung carrier and tossed into a fountain, along with his bearers. An eyewitness [Myconius; AK] reported that the spectators laughed so much that they could not stand. (Scribner 1978, 237–38)

At first glance, the whole procession can be read as a carefully planned carnivalesque inversion of the St Benno elevation a month earlier.57 Perhaps, as some researchers have assumed, given the absence of any printed reports about the events in Meißen, at least one of the members of the Buchholz mock parade had been an eyewitness (Kaufmann 2009, 355). A lack of printed news on the Meißen ceremony is also mirrored in the printed report on the events in Buchholz, for some of its elements were accompanied by a short explanation of their meaning. Readers obviously were in a different position to those present at the event itself, where humor (Roth 2017) and direct impersonations pulled people into the action. The preceding considerations, however, suggest that Poetscher’s public defense of the cult of saints and indulgence, his and other clerics’ reported debates on religious matters with ‘thoughtless people’ in Annaberg’s ale houses (ABKG vol. I, no. 718, p. 729, fn. 1), not to mention the oral transfer of news through travelers, merchants, and others ensured that enough information (even in the shape of rumor) about the Meißen ceremony must have spread throughout Buchholz and Annaberg.

On closer inspection, therefore, it is noteworthy that the whole mock procession is anything but a one-to-one invective translation of the Meißen procession.58 At Meißen the Dean of Magdeburg Cathedral, Eustach of Leisnig, had carried a silk flag at the head of the procession that showed a picture of Bishop Benno and a fish with a key in its mouth referring to the legend of St Benno (HAB, Cod. Guelf. 130 Helmst., fol. 41–43, Clemen 1908–1909, 336). In contrast, the Buchholzers wore various small rags and tatters, which could easily be procured spontaneously, producing the effect of a sea of flags rather than a direct parody of one huge flag that might include an inverted picture or something similar, which would have required a rather elaborate preparation. Similarly, sieves and bathing caps as a means to caricature the berets of scholars were readily at hand, with their indistinct meaning explicitly explained in the printed reports. Furthermore, some elements apparently played either no role in Meißen or only a minor one unworthy of comment, such as the (filthy cloth) baldachin or the (dung fork) candelabrum. Regardless of how extensive and careful the preparations had been, the mock procession served different purposes and relied on different communicative contexts, such as the religious tensions in Annaberg and Buchholz as well as the public debate on saints and indulgence in general and on St Benno in particular. Hence, the mock procession’s elements and the performative dynamic draw their meaning and energy from those different contexts and forms of media in which invective and polemic played an essential role.

The mock procession therefore represents, first, an implicit invective response to the Annaberg preachers of indulgence; second, an explicit scoffing of the Meißen ceremony; and third, the mockery of well-known elements of ecclesiastical rituals. Unsurprisingly, the supposed truth behind the façade of ecclesiastical ceremonies is exposed as a lie, which is why the events in Buchholz, with their elevation of a ‘holy arse-bone,’ are of course also a further accentuation of Luther’s initial critique. The choice of specific body parts was probably not accidental: When some participants of the parade held up a steer’s jawbone, they may have had in mind late medieval woodcuts showing the jawbone as an already well-known symbol for drunkenness and gluttony in a satire on Judges 15:18-19 (Hoffmann 1978, 195; Scribner 1994, 37–38). Whatever the intended meaning, in this case polemical comparison as a communicative technique used the humorous means of an inverted ritual that trod a thin line between severity and ludicrousness, while casually reinforcing the meaning of ritual in general. It did so, first, by serving to defend another truth (the Gospel) and, second, by using humor as a means to plainly communicate this simple truth. Given the background of the local conflicts outlined above, it is also worth emphasizing the function of providing emotional relief after months of hard attacks from the other side of the Sehma. Furthermore, evidence suggests that the Buchholz mock procession also served to consolidate a certain group solidarity at the outset of a period of major social conflict, foreshadowing the upcoming ‘revolution of the common man’ (Peter Blickle).59

When it comes to the question of the impact of the mock procession, the answer is twofold. First, Myconius’ original report made its way to Wittenberg60 and though its author remained unknown until the late nineteenth century,61 the story produced an immediate reaction in three printed pamphlets and a news song, with the latter (more than the pamphlets) contrasting Luther’s solus Christus principle with the cult of saints (ALB Dessau, Georg Hs. 101. 8°, fol. 45 recto-53 recto).62 The report was printed first in Wittenberg; further editions followed in Strasbourg and Worms (VD16 V 2625; VD16 V 2623; VD16 V 2624). With only minor differences in dialect and highlighted phrases, all three pamphlets consist of two parts. In the first, there is (in Peter Matheson’s words) a “glorified letter” by an anonymous writer to a nameless recipient in southern Germany, to which the unknown editor(s) of the Wittenberg edition added some remarks concerning the wider political issues discussed at the Imperial diets. Here, the pamphlets mocked the papal legate Aleander and warned the princes of causing unrest with their tyrannical behavior. In the second part, the pamphlets presented an anonymous eyewitness report of the incidents in Buchholz; this is the Myconius report in slightly different versions (Kästner and Schwerhoff 2021). Unsurprisingly, printers had an economic interest in capitalizing on the whole St Benno story that had been widely discussed in 1524. Luther’s harsh polemic against the celebration variously called it a “magic show” (gauckelspiel), a “play of fools” (narrenspiel), and a “monkey show” (affenspiel); the latter epithet not only ridiculed the veneration of St Benno but attacked it as satanic, for the devil was renowned as God’s monkey who satirized the divine order when and wherever he was able (Lünig 1724, 2:183, 197, and 192; Hoffmann 1978, 193–4). These invective attacks enraged Duke Georg, who had asked his fellow imperial estates to protect the published announcements of the venerations (and by implication the ceremony itself) from mockery and invective (Introduction to Luther 1524, 171). Strong responses came immediately from several prominent Catholic theologians, such as the Abbot of Altzelle, Paul Bachmann, who defended the cult of saints against the “wild slobbering boar” (wild geifernde Eberschwein) Luther (Bachmann 1524).

But however harsh polemic from both sides might have been, the attention of the Reformation public was soon absorbed by the troubling events of the Peasants’ War. The pamphlet reports of the Buchholz mock procession already hinted at the larger issues that were at stake. Remarkably, their editor(s) considered it necessary to add another invective against the veneration of St Benno when they reported that it was not Benno’s bones that were elevated at Meißen but rather the markedly smaller ones of a Slavic child. In a surviving copy of the first pamphlet in the library of Leipzig University, one or more contemporary readers added marginalia and underlined phrases of interest. One reader revealed himself to be an eyewitness of the events in Meißen and noted that he rejected the substitution of Benno’s bones as a lie, despite being pro-Lutheran. He nevertheless wrote that he enjoyed reading this “jocularis liber,” as did several Buchholz chroniclers such as Meltzer, Köhler, and others who have maintained the story in the collective memory, as well as other contemporary readers like Saxon poet Günther Strauß.63 Some 15 years later, he casually referred to it while joining the mockery of Meißen’s solemn Catholic ceremony by citing Luther’s foreword to the 1528 Wittenberg hymnal that one always finds mice droppings among peppercorns (Strauß 1524, fol. Aiv recto). Strauß recalled a “great practical joke” (gute lecherey) in Buchholz in 1524 regarding the Benno ceremony, though his reference lacks details. He clearly thought the entire episode to be a firmly embedded part of the communicative memory of his contemporaries (ibidem fol. Aiv verso).

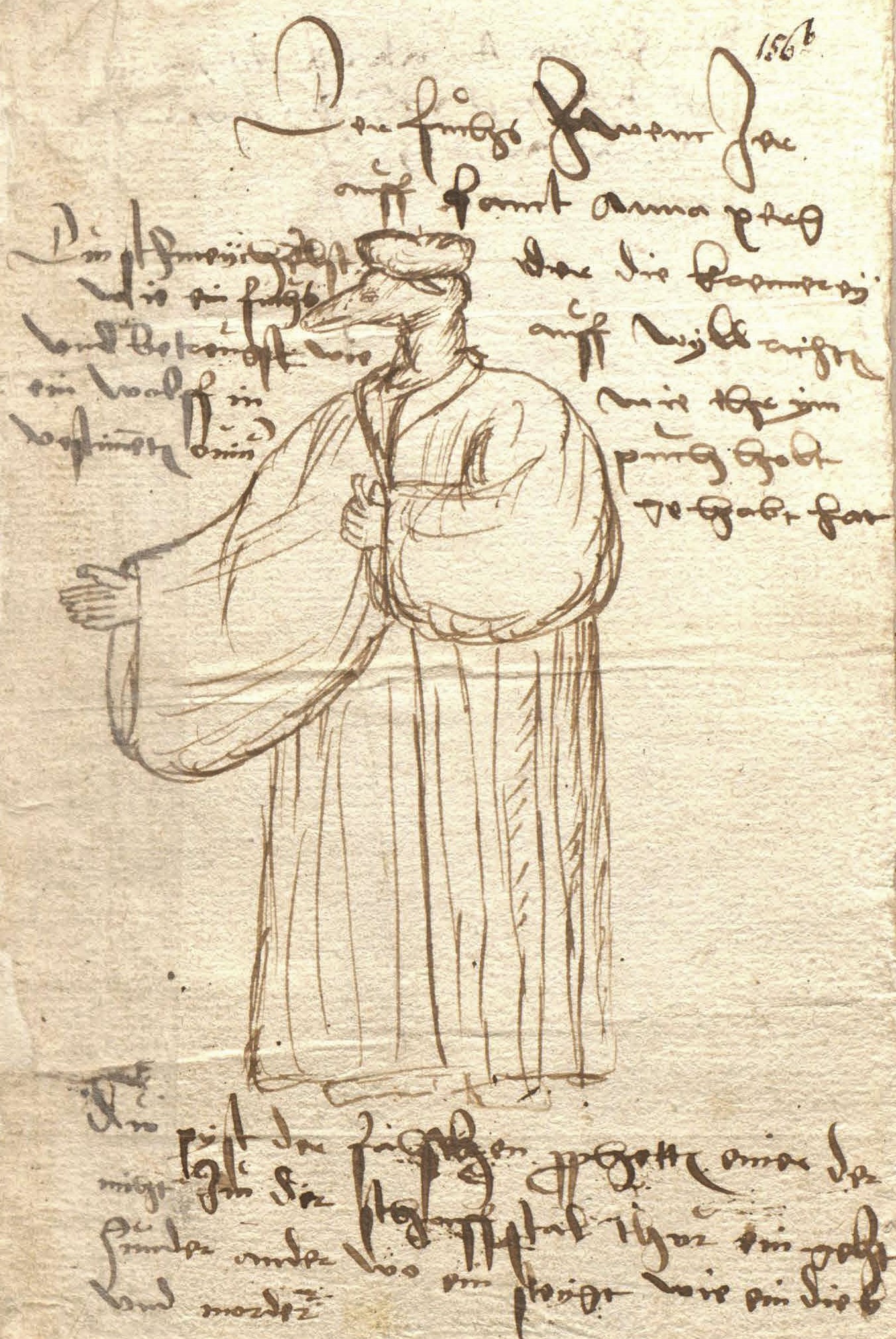

By contrast, a second example of the mock procession’s impact produces quite a different picture. Above all, the event played no significant further part in early Reformation Buchholz and was also not mentioned in any handwritten report after the summer of 1524, reflecting a significant lack of interest on part of the authorities already during that summer. Moreover, in their comments on the Buchholz heretics, preachers in Annaberg did not mention the mock procession at all, or if they did it was not reported. Disputes about the preachers, in particular Poetscher, nonetheless continued, and surviving sources simply frame the mock procession as one event in a series of statements concerning religious issues that were important for local people. This is illustrated by the invective adaption, discussed earlier, of an old letter of indulgence in which the anonymous taunter had called Poetscher a fornicator and drew a connection to the St Benno controversy. Another local poetaster who produced libelous verse also called Poetscher a fawner, and it is this polemical insult (figure 1) that illustrates the restricted possibilities for action in Annaberg itself, where a public mock procession would have been completely unthinkable. As with the other examples already adduced, this document needs to be carefully contextualized and read against the interpretations offered in previous research. In order to reconstruct its precise context, we must rely on several reports by Annaberg and Buchholz officials dating from August 10 to 13, 1524.64