A Spiritual Perestroika: Religion in the Late Soviet Parliaments, 1989–1991

The article discusses various meanings which were ascribed to religion in the parliamentary debates of the perestroika period, which included Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, and other religious and lay deputies. Understood in a general sense, religion was supposed to become the foundation or an element of a new ideology and stimulate Soviet or post-Soviet transformations, either creating a new Soviet universalism or connecting the Soviet Union to the global universalism of human rights. The particularistic interpretations of religion viewed it as a marker of difference, dependent on or independent of ethnicity, and connected to collective rights. Despite the extensive contacts between the religious figures of different denominations, Orthodox Christianity enjoyed the most prominent presence in perestroika politics, which evoked criticisms of new power asymmetries in the transformation of the Soviet Union and contributed to the emergence of the Russian Federation as a new imperial, hierarchical polity rather than a decolonized one.

Soviet Union, Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, empire

Introduction

In 1989, following the start of a constitutional reform in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) as part of perestroika,1 religious figures joined the open-ended political discussion in the country’s new parliamentary bodies and engaged in repositioning religion in the transforming Soviet state. Religion was never formally illegal in the USSR. With the exception of the violent anti-religious policies in the 1930s and early 1940s, the state and the ruling Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) recognized and interacted with several major organized denominations, including Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism, for most of the country’s history. As Geraldine Fagan argued, it was this selective recognition by the Soviet state which laid the foundation for the set of four “traditional religions” with privileged legal status in contemporary Russia (Fagan 2013, 4–5).

Religious leaders were also occasionally mentioned in the Soviet press, thanks to their participation in informal diplomacy and the state-sponsored peace propaganda (see, for instance, Izvestiia, December 7, 1960: 3; Izvestiia, October 1, 1980: 5). Despite limitations and state control, the representatives of the recognized denominations had numerous opportunities to exchange their ideas and consolidate their position on religion in general through different conferences and organizations since the 1950s, when Zagorsk hosted the First Conference of All Churches and Religious Organizations of the USSR for the Advocacy of Peace (1952) of 27 delegations from Soviet denominations and foreign representatives (“Konferentsiia vsekh tserkvei i religioznykh ob”edinenii v SSSR v zashchitu mira (khronika) [Conference of All Churches and Religious Organizations of the USSR for the Advocacy of Peace (Chronicle)]” 1952). Since the 1950s, Buddhism and Islam played an important role in the context of Soviet ties to many postcolonial states with which the USSR exchanged religious delegations. At the same time, the presence of religion in Soviet public space was miniscule, and religious activities remained under strict control of the state for most of the Soviet period (Bennigsen et al. 1989; Sablin 2019).

The situation changed dramatically during perestroika, especially with the launch of the constitutional reform by the CPSU under Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev in 1988. Although at the Nineteenth CPSU Conference (June 28–July 1, 1988), which can be seen as the starting point of an open political discussion, religion was only briefly mentioned as a need of minorities, which the party vowed to satisfy (Kommunisticheskaia partiia Sovetskogo Soiuza [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] 1988, 2:2:158), during the last four years of the USSR it became a buzzword in Soviet politics and law. Furthermore, it was the Law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations,” adopted on October 1, 1990 (SSSR 1990), which can be considered one of the few concrete results of the reform-era USSR legislature (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1991d, 86).

This article relies on the perspective of conceptual history, with its focus on active uses of language and conceptual innovation aimed at affecting policy and the assumption that “we create, (re)define, evaluate, (ab)use and reject concepts to construct much of our social reality and that human interpretations of the world and consequently the exact meanings of political concepts are unavoidably contested.” The mass digitization of parliamentary records launched a parliamentary turn in conceptual history. This source material, which became much more accessible and can now be analyzed with digital tools, allows tracing how past political actors, rather than canonical thinkers or present-day social scientists, formulated and used concepts. Following Pasi Ihalainen, this article approaches parliamentary debates as nexuses of past political discourses, that is, as meeting places in which multi-sited political discourses intersected in the same time and space (Ihalainen 2021).

In the context of perestroika, parliamentary debates became the site of transcultural contact not only in the ethno-national (Stefano 2020), but also the religious sense (Krech 2012). Representatives of different religious organizations and non-affiliated deputies debated the notion of religion and presented several understandings of and approaches to it in the diffused Soviet legislature, consisting of the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies and the reformed USSR Supreme Soviet on the central level and the bodies of the union republics, such as the Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic). The article uses digitized parliamentary debates in the three bodies to investigate qualitatively which specific meanings were assigned to the word “religion” and “religious” by individual politicians and specific religious organizations during the last years of the Soviet Union (Ihalainen 2021; for a recent qualitative study with similar methodology, see Palonen 2021).

Many deputies, but especially those who were affiliated with the officially recognized Orthodox Christian and Muslim organizations, defined religion in a general sense as spirituality which was supposed to replace the Communist ideology and become the driver of state and social transformations. In practical terms, a concert of denominations was supposed to represent religion in general. The idea of a concert of denominations corresponded to the institutionalized diversity of the multinational Soviet State and the multireligious representation in the parliaments. Religious figures also highlighted individualized religious freedom, which was supposed to connect the USSR with emerging post-authoritarian globality (Fukuyama 1989), but the human rights interpretation remained marginal. Even though there were atheist voices as well, the primacy of the major organized religions in the debates ensured that perestroika increasingly meant desecularization, which put its beginning even before the collapse of the USSR (Kormina, Panchenko, and Shtyrkov 2015).

Religion was also seen by some participants of the debates as a primary or secondary marker of difference. As such, it was supposed to ensure a redefinition of collective political rights of religious or ethno-national groups, effectively decolonizing them; and, in some cases, also to reconnect these groups to the transboundary religious communities, those of Islam and Buddhism in the first place. In a situation of religious contact, the concrete meanings of religion were contested. Whereas the eventual conflict between established (“traditional”) organizations and other religious communities (Di Puppo and Schmoller 2020) was not evident in perestroika debates, the asymmetry between the Orthodox Church and other organizations played a key role in the contestation.

The much larger presence, compared to other organizations, of the Orthodox Church in the parliaments and the explicit claims of Orthodox figures to monopoly on religious ritual implicitly relied on the supposed share of the population professing Orthodox Christianity in the USSR as a whole and especially in the RSFSR, but the 1979 and 1989 general census did not collect information about religious affiliation. In practical terms, it relied on the pre-perestroika asymmetries: the Orthodox Church had the largest organizational structure in the USSR and acted as the de facto main religious organization in the post-1945 Soviet public sphere, especially in the Soviet peace movement (Fagan 2013). Desecularization hence did not necessarily mean decolonization, as the asymmetric presence of Orthodox Christianity engendered new hierarchies. This was especially true for the RSFSR, which was being reimagined along Russian nationalist lines with the symbolic participation of the Orthodox Church, and which Buddhist and other deputies opposed. Furthermore, there was no Buddhist representation in the USSR bodies, which resulted in the virtual absence of this denomination from the larger desecularizing Soviet space.

The concepts of the imperial situation and imperial universalism prove especially helpful in discerning the meanings of religion. The idea of the imperial situation complicates the notion of empire, understood as the hierarchical governance2 over and through difference, by suggesting that the composite society of the empire finds itself in constantly unstable balance. Social categories in the imperial situation are not holistic entities, since social boundaries are “conditional, fluid, and situational,” (Gerasimov et al. 2012, 19) and hence the difference itself is fluid and dynamic (Burbank and Cooper 2010; Gerasimov et al. 2009; 2012, 19–20). In this dynamic context, imperial universalism can be seen as an ideology of standing above difference and particularisms, which was used by elites or other groups in their attempts to stabilize and control the imperial situation (Crossley 2000, 37–38, 50–51).

Both the crisis of Soviet universalism (Webb and Webb 1936; Wallensteen 1984) and the rise of national particularisms, which were produced by the nation-centric Soviet system itself (Suny 1993), can be seen as the main drivers of, first, perestroika and, then, the dissolution of the USSR. Religion in this respect can illustrate very well the inherited entanglements between universalisms and particularisms (Laclau 1992, 86). In the context of perestroika, religion was frequently understood as a new ideological foundation (or perhaps a new ideology). In the universalist sense it could appeal both to religion in general, a synonym for a moral code, and to concrete religions, the anticipated concert of the religions which were practiced in the USSR. These religions were supposed to become the source of the new ideology and provide solutions to moral and material problems. In these general and collective understandings, religion did not, however, necessarily point to a new universalism for the reformed Soviet or a new Russian empire. Religion was also used to inscribe the transformed (post-)Soviet space into the globalized Western-centric universalism of human rights, with its individualized attitude towards religion (Renteln 1989).

In the context of the imperial situation, however, religion was also a potent marker of difference. As such, it denoted inter alia a separate self-sufficient category and inscribed its members into one of the global religious communities, appealing thereby to religious universalisms which spanned across the Soviet borders. Religion could also be a secondary marker for ethno-national categories, and as such it could be used in the construction of national particularisms (Agadjanian 2001). Just like in the case with the general understandings of religion, the claims to religious and national self-determination can also be seen as part of the anticipated universalism of human rights, albeit formulated not through individual but through the collective attitude towards religion (Dinstein 1976). These particularistic understandings of religion engendered power asymmetries (Brosius and Wenzlhuemer 2011), which translated into political tensions when the relations between concrete organizations came into question.

Given the interconnectedness between universalistic and particularistic understandings of religion, the current article splits the empirical material into two sections without implying a strict differentiation between the different approaches to religion. Furthermore, individual deputies interpreted religion in multiple ways. The first section hence unites the overarching understandings which use the term religion in general. It focuses on debates of morality and briefly discusses some of the concrete meanings which were attached to religion in its relation to the state. The second section focuses on the interactions between different denominations, anticipated to be in concert, and deals with the tensions between the groups practicing different religions and between those who claimed to represent them. It also addresses the understandings of concrete religions as attributes of specific nations.

The Soviet legislative bodies prove especially fruitful for exploring the multiple meanings of religion due to their open-ended debates and the diverse backgrounds of their members. The parliamentary debates can be understood as concrete manifestations of the imperial situation, since their participants articulated and perhaps even discovered different social categories in the context of a direct religious contact. The article studies the verbatim reports of three institutions – the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, the USSR Supreme Soviet, and the RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies.3 The USSR Congress of People’s Deputies was formally the supreme government body of the USSR in 1989–1991. Although only two thirds of the 2,250 deputies were elected, with the rest having been nominated by different organizations, while no parties other than the CPSU had access to the elections, it can be considered the country’s first parliament. Despite the issues with representation, with deliberation (due to the short sessions), with its sovereignty within the system (due the continued presence of the CPSU), and with the responsibility of the cabinet to it, the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies proved to be a deliberative institution of dissensus (Ihalainen, Ilie, and Palonen 2016) and a major forum where Soviet citizens had the opportunity to express their concerns freely and to the largest imaginable audience, thanks to the live broadcasts of the First Congress and the extensive coverage of the other four. The bicameral USSR Supreme Soviet, as the permanent parliament which was formed by the USSR Congress for developing and adopting legislation, was also a site of dissensus and deliberation (Lentini 1991).

The RSFSR was the only union republic which had its own Congress of People’s Deputies. Due to the power struggle within the Soviet elite and to the especial complexity of the RSFSR, comparable to the complexity of the USSR at large (Hale 2005), the RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies at times openly challenged the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies and acted as an alternative parliament. Unlike its USSR counterpart, the RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies of 1068 members was the first functioning legislature in Russian history which was elected through direct, universal, equal, and contested elections (Myagkov and Kiewiet 1996). The debates in the RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies highlighted both the level of a union republic and an alternative approach to the open-ended transformation of the USSR, which could have followed a decolonizing logic and that of the formation of a new imperial regime in which Orthodox Christianity or the “traditional religions” would have been considered a cornerstone of empire-building (see Sablin 2018). Furthermore, the RSFSR Supreme Soviet passed its own Law “On Freedom of Religions” soon after its USSR counterpart, and the two documents had significant differences, with the RSFSR one exhibiting a more desecularizing approach (SSSR 1990; RSFSR 1990).

General Meanings: Religion in a New Ideology

Several generalized meanings and connotations of religion pointed at its general character and sought to position it in the ongoing reform of the USSR and its parts. Here, the issues of ideology and morality proved especially important, as well as the relations between religion and the state. In general terms, religion was not necessarily understood as a single whole and the idea of a “concert” of the different religions practiced in the USSR was also present in the debates. Although perestroika called for broad public participation in the reforms, it was inherently an etatist movement. The possible use of religion as an element of revised Soviet universalism or as the foundation for a new universalism fueled the discussion of the relations between religion and the state.

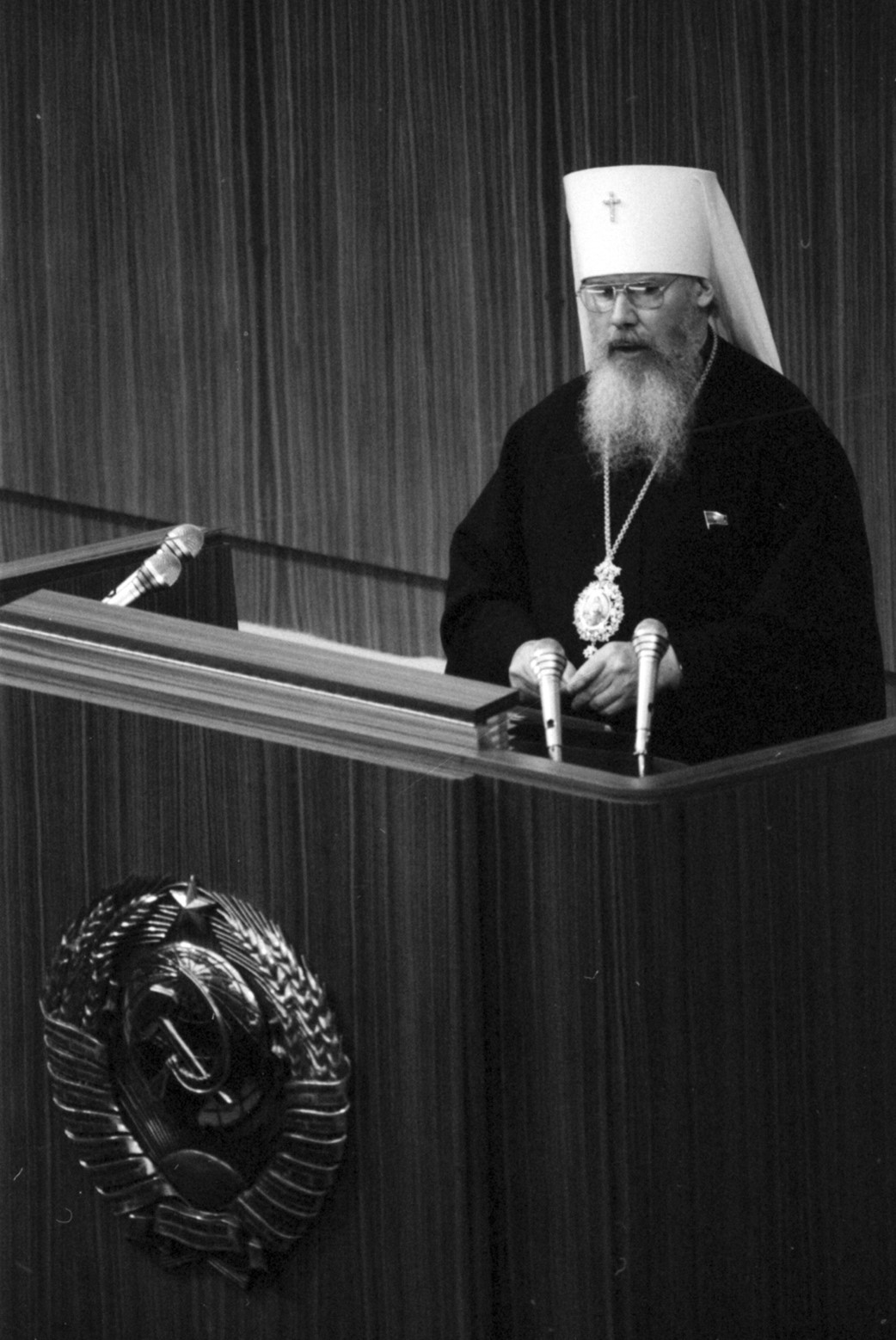

All three legislative bodies, the USSR and RSFSR Congresses of People’s Deputies and the USSR Supreme Soviet, included active religious figures for the first time since the parliamentary institutions of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War. Their numbers were, however, not particularly high. In the USSR Congress, seven religious figures served as deputies, while in the RSFSR Congress there were five (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989a, 1:43; I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:86). Addressing the First USSR Congress of People’s Deputies (May 25–June 9, 1989), Alexei Mikhailovich Ridiger (then Metropolitan Alexy and, since June 10, 1990, Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus’ Alexy II) (Figure 1) noted that it was for the first time (in Soviet history) that a religious figure could speak from such an honorable rostrum (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989b, 2:55). The non-Orthodox religious figures at the USSR Congress included Mukhammad-Iusuf Mukhammad-Sodik (Chairman of the Presidium of the Spiritual Board of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan) (Figure 2), Allakhshukiur Gummat ogly Pasha-Zade (Sheikh Ul-Islam, Chairman of the Spiritual Board of the Muslims of Transcaucasia), and Levon Abramovich Palchian (Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians Vazgen I). Additional religious figures were invited to participate in the debates on the Draft Law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations” at the USSR Supreme Soviet. They included Grigorii Ivanovich Komendant (Chairman of the All-Union Council of the Evangelical Christians-Baptists), Mikhail Petrovich Kulakov (Chairman of the All-Union Council of the Seventh-Day Adventists), and Adol’f Solomonovich Shaevich (Chief Rabbi of the Moscow Choral Synagogue) (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:83). It is noteworthy that no Buddhist religious figures were represented in the two central Soviet parliaments.

Religious organizations were not among those which could send their representatives to the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, so the representation of religious leaders was situational. Metropolitan Alexy, for instance, was nominated without contestation by the Soviet Foundation for Charity and Health (Ivanchenko and Liubarev 2006, 21). Mukhammad-Sodik was elected in the Tashkent Region of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and introduced himself as the representative of the “multimillion Muslims” of the USSR (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989a, 1:63).

Metropolitan Alexy positioned religion in perestroika in his speech at the First USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, asserting that together with economy and democratization, perestroika included the “moral renewal” of the society. According to Alexy, Soviet history demonstrated that morality and social development had a “profound relationship” to one another and that “the most beautiful social ideas” could not “be realized by means of coercive methods without referring to human morality, conscience, reason, moral choice, and inner freedom.” It was therefore “spiritual impoverishment” which was a major contributing factor to the difficult economic situation. Alexy maintained that morality and “moral principles” were supposed to “overcome human separation and spiritual alienation and thus unite us as brothers and sisters to build a happy future for ourselves and for our descendants.” Alexy stressed the universalism of morality, suggesting that everyone should “build their relationships with others, with the society, with nature on the basis of a universal moral code.”4 He also declared that the (Russian Orthodox) Church and religious associations of other denominations were ready to contribute to moral renewal and anticipated the adoption of the legislation on the freedom of conscience, which was needed for this (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989b, 2:56–57). At the Second USSR Congress of People’s Deputies (December 12–24, 1989), Metropolitan Alexy connected the moral crisis to the rise of criminality, suggesting that religious knowledge would help prevent crime. He also pointed to the meeting between Gorbachev and the representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church on April 29, 1988 as the starting point for the involvement of the Church in revival (II S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [Second Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989, 3:557–58).

Even though in both speeches he discussed religion in general, Alexy’s references to the Russian Orthodox Church as the harbinger and the leader of the reforms can be interpreted as the construction, or rather the reaffirmation, of the hierarchy of concrete denominations in the USSR. The large-scale return of religion to Soviet public space can be connected to the massive celebration of the 1000th Anniversary (Millenium) of the Christianization of Rus’ in June 1988, in which the Soviet government participated. Although the claim of the Russian Orthodox Church to the celebration of the event was challenged, in particular by Ukrainian commentators, it was staged as a Russian Orthodox (rather than a Ukrainian, Belarusian, or Catholic event) already during the planning. Over 4000 new parishes were established during and after the Millenium (Lupinin 2009, 32; Sorokowski 1987, 257). The Russian Orthodox Church had also mediated the talks between Pasha-zade and Vazgen I in the context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict since 1988. Like most Soviet conferences on religion, it was the Russian Orthodox Church which hosted the Meeting of Representatives of Religions, Churches, and Religious Associations of the USSR on December 7, 1989, ahead of the Second USSR Congress of People’s Deputies (Silant’ev 2010, 72).

Other religious figures prepared speeches with a similar generalized understanding of religion for the First USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, and although they had not been delivered (like the speeches of dozens of deputies), they were published as part of the proceedings. The Moldovan Priest Petr Dmitirevich Buburuz stressed that the revival of moral norms had to run parallel to the establishment of the rule of law. He specified that the social role of the Church (probably meaning both the Russian Orthodox Church and religion in general) had to be increased through religious education and upbringing, and that it could play an important role in charity, preservation of cultural heritage, environmental protection, and disarmament and peace campaigns (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989c, 4:172–75). The latter marked continuity with the pre-perestroika period, when religious figures were involved in the official Soviet peace campaigns.

Mukhammad-Sodik celebrated the inclusion of believers into Soviet society through perestroika, the reopening of places of worship, and the participation of religious organizations in multiple spheres, including inter alia the promotion of the “friendship of the peoples.” He summed up the general religious position: “We, religious figures, think that many undesirable phenomena in our society arise from the lack of spiritual and moral education. Therefore, the struggle for spiritual purification of our people is the most important task for all of us” (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:377–78, 380–81). Konstantin Vladimirovich Nechaev (Metropolitan Pitirim) raised similar issues, putting the morality of everyone at the center of all developments in the country and adding that the compatriots abroad were watching the country’s spiritual revival (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:390–92). Pasha-Zade noted that both perestroika and the “moral purification” of society were irreversible, and that religious norms would guarantee it (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:463–64).

As noted above, no Buddhist religious figures participated in the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies. The Buryat Erdem Dashibalbyrovich Tsybikzhapov (Deputy Chairman of the Central Spiritual Board of Buddhists of the USSR), who was elected to the First RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies (May 16–June 22, 1990), explicated the universalist argument in favor of religion, arguing for political rights for believers, but remained cautious about its ability to resolve the multiple crises of the Soviet state and society.

Although some scientists and many other [people] claim that there is no soul, humans need spirituality. It separates us from the animal world. In addition to food and sleep, a person should have something that would elevate him above it. […] But I do not mean to say that religion can lead us out of the impasse we are in. Religion has a direction where it can provide some educational, cultural, moral help to the entire population, including young people. Religion has never made a human evil or dangerous to society. It simply brought up, created an atmosphere in which a human became a person (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:180–81).

The discussion of morality was not exclusive to religious figures: Soviet dissidents had employed the notion of conscience before perestroika (Boobbyer 2005). Some lay deputies supported the moral approach to perestroika in the Soviet parliaments. Murad Rasil’evich Zargishiev of Dagestan also spoke of the “moral impasse” and the rights of believers, including educational and publishing activities, at the First RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies, and called for a special committee to be created in the RSFSR Supreme Soviet, which was eventually created, unlike in its USSR counterpart (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:427, 429). The Third RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies (March 28–April 5, 1991) nevertheless did not support the initiative of Valentina Viktorovna Lin’kova to issue an official statement of apology for the long-term violation of religious feelings to the “believers and clergymen of all religions operating in the Russian Federation” (III (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Third (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 5:94). During the debates of the Soviet law on religion in the USSR Supreme Soviet in May 1990, the Tajik filmmaker and politician Davlatnazar Khudonazarov maintained that the long-time struggle against religion ended in failure and that religion was a sphere that was not filled with anything else (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:253). The Kalmyk poet David Nikitich Kugul’tinov, who was a deputy of both the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies and the USSR Supreme Soviet and claimed to represent Buddhists in the debates on the USSR religious law, stressed that the state needed conscience (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:255).

Some lay deputies drew explicit connections between religion and ideology. One deputy noted in a non-delivered speech, prepared for the First USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, that Marxism-Leninism was not omnipotent and that a dialogue with representatives of a religious worldview was needed (I S”ezd Narodnykh deputatov SSSR 1989e, 6:417). Another asserted at the Second USSR Congress of People’s Deputies that the CPSU proved passive and applauded the constructive initiatives of the religious figures (II S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [Second Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989, 3:563).

Most of those who connected religion and ideology, however, used the former as an abstract concept denoting irrational beliefs and the institutions based on them. In this respect, religion was mainly used to criticize the CPSU. Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov, the famous dissident, openly claimed that the CPSU and the church were organizations of the very same type (II S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [Second Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989, 3:185). The Georgian Tengiz Pavlovich Buachidze argued that any ideology could acquire features of a religion. He even called the presidency in the USSR, established by the Third USSR Congress of People’s Deputies (March 12–15, 1990), a “secular” authority, implying its independence from the CPSU (III (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [Third (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1990, 2:165). In her non-delivered speech for the First USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, the Tajik poet Gulrukhsor Safieva explained that the project of a new, secular religion had failed because the human was forgotten in the process. At the same time, Safieva doubted that religion could be an alternative to ideology, since it was a spiritual category not suited for playing “a progressive role in the material world” (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989e, 6:161–62). These negative connotations attached to the very notion of religion were rooted in Soviet atheist discourse (Smolkin 2018). Iurii Ivanovich Borodin, a medical doctor, expressed a rare positive opinion of ideology in connection to religion. He compared Christianity and Communism as ideologies with the same roots and goals and urged the CPSU to revive Communist ideals (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:182).

Some deputies suggested that religious expertise was indispensable for the resolution of the many violent conflicts which accompanied the crisis and collapse of the USSR, inviting religious figures to participate in the investigation of the Tbilisi Massacre—the violent dissolution of a demonstration on April 9, 1989 by the Soviet Army. Metropolitan Alexy was also included in the commission of the Congress of People’s Deputies for investigating the Nazi–Soviet agreements of 1939 (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989a, 1:549; 1989b, 2:192, 876), but in this context probably as an influential native of Estonia rather than a religious figure. Nikolai Nikolaevich Gubenko, who was nominated as the USSR Minister of Culture, stressed that he was in contact with the (Russian Orthodox) Church and urged restoring spirituality during the discussion of his candidacy in the parliament (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1989c, 226). After his confirmation, he suggested inviting religious figures as experts for determining what materials were pornographic as part of the state initiative of boosting public morals (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1991b, 8:64, 70). At the same time, Mukhammad-Sodik’s proposal to establish a permanent committee on religious affairs in the USSR Supreme Soviet was not adopted (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:379). Zargishiev’s proposal of a similar committee in the RSFSR Supreme Soviet (V (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Fifth (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:429), by contrast, was incorporated into the RSFSR law on religion (RSFSR 1990).

The RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies gave religion a more prominent role compared to the USSR institutions in general (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992b, 2:278). The debates on the RSFSR Declaration of State Sovereignty (ratified on June 12, 1990) included the issue of access of religious organizations to governance, and the final text guaranteed that all “RSFSR citizens, political parties, civil and religious organizations, mass movements, operating within the framework of the Constitution of the RSFSR,” had “equal legal opportunities to participate in the management of state and public affairs” (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1993, 4:180, 184, 478). The debates in the USSR institutions before and after the RSFSR declaration dealt with the matter as well, but the suggestions to allow religious organizations to participate in elections and to sponsor political parties did not pass (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:243; 1990h, 3:111–12).

Both the USSR and the RSFSR laws made religious organizations legal persons. Further discussions of adapting the Soviet state to the program of spiritual revival included the issues of military service, supervision, and education. Whereas the proposal to include alternatives to military service for religious reasons did not pass in the USSR legislature (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1989b, 195), it was introduced in the RSFSR law. In a similar manner, the USSR law on religion retained an official body for religious affairs under the Soviet cabinet, even though it was made consultative (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:253; 1990h, 3:91; SSSR 1990), whereas the RSFSR law abolished such a body in Russia (RSFSR 1990).

The issue of education proved especially contentious. Mikhail Antonovich Denisenko (Metropolitan Filaret of Galicia and Kiev, Exarch of Ukraine, then the locum tenens Patriarch of Moscow and All-Rus’, and later the Patriarch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church), who was an invited speaker at the debates on the Soviet law on religion, called for permitting religious education in public institutions (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990d, 15:205). Alexy voiced the same suggestion (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:93; 1990i, 3:169). Mukhammad-Sodik was even more direct, claiming that his voters of different faiths demanded that religion was taught in schools (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:252).

Among the opponents against the provision in the initial draft that school buildings could be provided for teaching religion, let alone against religious education in public schools, were the teacher Igor’ Mikhailovich Bogdanov, the physicist Sergei Mikhailovich Riabchenko, the cosmonaut Svetlana Evgen’evna Savitskaia, and other deputies. The provision was ultimately excluded (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:119–21; 1990i, 3:173, 181). The proposals to allow history of religion in public schools for education in moral values also did not pass (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990d, 15:209; 1990c, 15:254; 1990h, 3:112, 119).

The supporters of returning religion to school in the RSFSR bodies (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992b, 2:283; II (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Second (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:221) succeeded only partially. The amendments to the RSFSR Constitution kept state education secular, with Dmitrii Egorovich Stepanov even maintaining that he still considered religion to be “opium for the people,” but the RSFSR law on religion allowed teaching religion from academic perspectives and explicitly allowed elective courses in religion at all educational institutions, which made the separation flexible (II (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Second (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992b, 5:187–92; 1992c, 6:248; RSFSR 1990).

Despite the official Soviet state’s celebrations of its own success in atheist policies (Smolkin 2018, 117–18, 180), the majority of those who spoke on religion in non-neutral terms in the late Soviet parliaments did so favorably, while the RSFSR parliamentary bodies took steps towards desecularization. Direct opposition to religion was rare. Riabchenko, for instance, urged not to make religion equal to morality and rejected the former’s monopoly on the latter (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990i, 3:171). The discussions also reflected in the press. Stanislav Nesterovich Pastukhov, a Pravda commentator, noted that religious education in public schools would lead to chaos in the context of religious diversity and, quoting Riabchenko, reminded his readers of religious conflicts and violence (Pravda, October 7, 1990: 2).

The relations between religion and atheism nevertheless proved contested. Vladimir Aleksandrovich Voblikov called for protecting the rights of atheists in the USSR law on religion (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990d, 15:207). Riabchenko urged protecting the scientific worldview in the context of banning state-sponsored propaganda of atheism in the new law, which resulted in clarifications on the status of science and guarantees for it (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:91, 106–10). The Chechen Sazhi Zaindinovna Umalatova, who called herself a Muslim, raised the issue of religious upbringing in families, but her proposal to protect children from imposed religion did not pass. Neither did her proposal to ban religious rituals in all official activities (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:103–6).

Particularistic Meanings: Religion as a Marker of Difference

The ideas of a multireligious unity experienced similar challenges as those of a multiethnic one. Religion in concrete terms was frequently understood as a secondary marker of ethnicity or nationality, which projected interethnic tensions and conflicts onto religious interactions. Furthermore, some were critical of the predominance of Orthodox Christianity and new asymmetries. Others viewed their religions as spanning the borders of the USSR or the RSFSR, thereby supporting respective religious universalisms.

The position of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was often seen as the main speaker for religion, was ambivalent. Vladimir Mikhailovich Gundiaev (Archbishop, since 2009 Patriarch of Moscow and All-Rus’ Kirill), who addressed the Second RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies (November 27–December 15, 1990) on behalf of the Russian Orthodox Church as an invited speaker, declared that the (Russian Orthodox) Church was neutral in politics. According to Kirill, it rejected the roles of leader and political alternative due to its eternal objectives. At the same time, he called for restitution of church property as an act of “of popular repentance” (V (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Fifth (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:276–77, 279).

The Fifth RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies (July 10–17, October 28–November 2, 1991), which during its first period of convocation swore Boris Nikolaevich El’tsin in as the popularly elected Russian President, invited Alexy II, then already the Patriarch. Alexy II addressed the Congress of People’s Deputies and El’tsin from Christian positions, claiming that the President was responsible not only before the people but also before God, and expressed his conviction that the President would foster the restitutions to the Church and other religious organizations. Even though Alexy II read an address from the Christian (Orthodox, Catholic, and Baptist), Muslim, Buddhist, and Jewish religious figures who were present at the assembly, he blessed El’tsin with the sign of the cross when passing the text to him (Congress of People’s Deputies RSFSR V, 1: 6–8). This moment was televised and photographed. The address itself relied on a general understanding of religion.

Dear Boris Nikolaevich! By the election of the people and God’s will you are awarded the highest political authority in Russia. Russia is not just a country, it is a continent inhabited by people of different nationalities, different convictions and faiths. We all wish a peaceful and favorable future for it, and we all pray for you and hope that you will serve the good of our Motherland, its speedy recovery from the painful wounds that were inflicted on it in the previous years of struggle with the spiritual foundations of human life. … The ideals of equality, freedom, and spiritual revival that you promised in the days leading up to the elections will hopefully be the constant pointers for you in all the years of your work as Russian President (II (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Second (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:8)

Given the asymmetries in favor of Orthodox Christianity on the USSR and RSFSR levels, the question of which concrete institutions were understood as religions came up frequently during the debates. The advocates of the general approach supported the idea of a concert of religions, which was connected to both the ideas of patriotism and the Soviet concept of a multiethnic people. In an undelivered speech, Pasha-Zade called the deputies the children of one God and one motherland and urged for unity of the “representatives of different peoples” and “of different convictions and beliefs” for the sake of the common goal. Pasha-Zade then continued that it was the duty of the heads of all denominations to work together for “bridging the gaps in the society,” so that religion could not be used to aggravate national tensions (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:461–63). In another undelivered speech, Mukhammad-Sodik stressed that he was backed by voters of diverse nationalities and religions. He then urged Vazgen I and Pasha-Zade to do everything in their powers to resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between the Armenians and the Azerbaijanis (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:377–80). The idea that the multiple religions in concert would strengthen the state was voiced both at the USSR and the RSFSR institution. Some deputies stressed the need for a multireligious revival in their home republics or regions (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:428; Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990b, 10:95–96; 1990h, 3:112).

The supporters of the concert approach made religion and nationality part of the same diversity conglomerate, in which religion was often a derivative category. Tsybikzhapov, for instance, claimed that religion was “the spiritual and cultural heritage that all peoples have had, the faith that has been traditionally passed down from the older generation to the newer generation, must be restored.” It was hence in the same realm of tradition as were language, music, and “national dress” (V (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Fifth (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:180)—the markers of difference which were at the core of the Soviet understanding of nationality, especially during the later decades. Zargishiev also viewed religious and national cultures as deeply interconnected (V (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Fifth (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:428).

Such a view was common for the those claiming to represent the Russian nation as well. Viktor Vladimirovich Aksiuchits, a Christian dissident, deemed the spiritual revival “religious-national” and argued for traditional values against ideology or revolution (V (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Fifth (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992b, 3:425, 427). Bela Anatol’evna Denisenko, a medical doctor, spoke of the Russian “ethnos” and claimed that the interest to religion was part of the Russian national resistance to Bolshevism (III (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Third (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992b, 2:121). There were voices which cautioned against equating religion with nationality and making the latter the only organizing principle. Fedor Vladimirovich Tsann-kai-si, for instance, opposed ethno-national essentialism and claimed that the Russian federation had to be rebuilt on multiple principles, including territoriality and religion, rather than just nationality (V (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Fifth (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992b, 3:166–67). Most speakers, however, remained in the realm of Soviet discourse and, when speaking about concrete religions, viewed them as part of particularistic ethno-national communities.

The attempts to assert and contest religious asymmetries featured prominently in the discussions. Buburuz, for instance, proposed making Easter and Christmas public holidays (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989f, 3:175). Pitirim stressed in an undelivered speech that the 1988 meeting between Gorbachev and the leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church, marking the 1000th anniversary of Christianity in Russia, was a testimony of the Church’s historical role (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:392). After Aleksandr Grigor’evich Zhuravlev used “Russia” as the historic name of the USSR and asked Pitirim to bless the Congress of People’s Deputies ahead of Christmas, however, the Kazakh composer Erkegali Rakhmadievich Rakhmadiev rebuked such “imperial chauvinism” and asked if this meant that Pitirim was to convert Muslims and Buddhists to Christianity (IV S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [Fourth Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1991, 2:164, 188–89).

The presence of different denominations in parliament and the public sphere was unequal. Tsybikzhapov noted that he was the only non-Christian religious figure in the RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:180). Kugul’tinov claimed that the USSR Supreme Soviet would have felt “uncomfortable” if a representative of the Buddhists had not participated in the debates on the USSR law (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:254). Some deputies noted the presence of Orthodox priests on TV as a positive development but called for the representation of other religions as well (II (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Second (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992d, 4:97). The issue of inequality was not necessarily centered on Orthodox Christianity. Other established organizations claimed their own centralisms. Mukhammad-Sodik, for instance, opposed the idea of registering small religious organizations, pointing out the dangers of their independence and uncontrolled interpretations of religion (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990c, 15:253).

Riabchenko’s abovementioned argument against religious education in public school buildings revolved around the idea that different groups would have unequal access to them. The Adventist Kulakov, who was invited to the debates on the Soviet law on religion, voiced a similar concern, but instead proposed allowing full school education in religious institutions (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:92, 98). The very discussion of the access of religious organizations to public schools involved inequality. Bozorali Solikhovich Safarov of Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), for instance, claimed that for Muslims it would make no sense, as their religion could not be taught in rooms with portraits. The introduction of such norms would ultimately mean unequal treatment of five (predominantly Muslim) union republics. He even exclaimed, “It’s not just one faith here!” (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990i, 3:172). Similar concerns of possible unequal access were voiced against the introduction of religious ceremony to the military (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990i, 3:160–61).

In order to reassert their denominations in the public political space of the transforming USSR, the leaders of Muslim and Buddhist organizations followed a similar strategy to that of the Russian Orthodox Church. Following the 1988 celebration of the 1000th anniversary of Christianity in Russia, the Tatar and Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics (ASSR) hosted the festivities honoring the 1100th anniversary of the conversion of Volga Bulgaria to Islam in 1989, which made its history on the Russian territory older than that of Christianity. During the celebrations, the position of Islam in the USSR was further reinforced through its inscription into the global religious universalism through the invitation of high-ranking guests.

The idea of a global Muslim community was also prominent for some deputies. In an undelivered speech, Mukhammad-Sodik, for instance, applauded the authorities of the Uzbek SSR for reopening mosques and returning Osman’s Quran to the believers. He then raised the issues of the hajj restrictions and the lack of religious literature (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989d, 5:378–79). Magomed Bagandalievich Bagandaliev of Dagestan passed an appeal of a group of Muslims to the RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies, in which they also demanded lifting the restrictions on travelling for hajj (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989f, 3:58–59). Nikolai Nikolaevich Engver of Udmurtia raised the issue of more Quran copies requested by his Muslim voters, which could possibly be resolved with the assistance of Saudi Arabia (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990e, 3:161). Some connected the idea of global religious unity to international relations. Abdul-Rakhman Khalil ogly Vezirov of Azerbaijan lamented the destruction of Muslim sacred sites in the Gulf War (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1991a, 2:73).

The 1989 celebrations also commemorated the 200th anniversary of the Spiritual Board of the Muslims of the European Part of the USSR and Siberia, which was thus traced to the Orenburg Muslim Spiritual Assembly, which practically meant the official recognition of Islam as one of the religions of the Russian Empire (Werth 2014). A similar anniversary, the 250th anniversary of the official recognition of Buddhism in Russia, was celebrated in the Buryat ASSR in 1991, with the Fourteenth Dalai Lama playing a prominent role at the festivities (Kovrov 1991). The idea of Buddhist transboundary unity was reinforced by Tsybikzhapov in the parliament. He stressed that Buddhism was a culture of the Orient, that Russia was not only a European but also an Asian country, and criticized the lack of diversity in the solemn swearing of the President, meaning Alexy II’s actions (II (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [Second (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:278–79).

The violent context of the Soviet transformations was especially challenging for the concert of religions as the new universalism or a part of one. The many interethnic conflicts, some of which became extremely violent, had a religious dimension. A group of Soviet deputies that went to the Fergana Region, for instance, reported to the parliament that the mobilization against the Meskhetian Turks and the Russians was carried out by pro-Islamic organizations (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1989a, 50–52). The tensions between the Armenians and the Azerbaijanis, which had been discussed in religious terms, were not confined to Nagorno-Karabakh itself. The Nagorno-Karabakh deputy Genrikh Andreevich Pogosian, for instance, pointed to the loss of Armenian Christian churches in the Nakhchivan ASSR of the Azerbaijani SSR as an example of religious institutions of one confession being mismanaged by the representatives of another one (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1989d, 3:91). Alexy spoke of the events in Western Ukraine and accused the supporters of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, namely the Ukrainian national organizations, of inciting the takeover of the churches of the Moscow Patriarchate and the supposed forced conversions (II S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [Second Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1989, 3:559–61). Mikhail Konstantinovich Pashaly appealed to Alexy, then already the Patriarch, for action against the attempts to subordinate the Church in Moldovan SSR to Romania on behalf of his Gagauz and Bulgarian voters (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:100). Some deputies evoked these conflicts when calling for strengthening the equality of all religions (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990h, 3:92).

The issues of the (then still potential) dissolution of the USSR and RSFSR also had a religious dimension. En Un Kim discussed the future of Osman’s Quran, a relic for all Soviet Muslims, in case Uzbekistan left the union, and suggested keeping it in the USSR (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990g, 3:215). Ianis Ianovich Peters of Latvia argued that the independence of the Baltic states required guarantees for minorities, including their right to exercise their own religion (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990f, 3:271). Vasilii Ivanovich Belov, a Russian nationalist writer, feared the possible dissolution of Russia and its turning into a territory between “the shared European home” and the “Muslim region,” urging the RSFSR Supreme Soviet to prevent it (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1990a, 1:244). After the departure of multiple republics from the new union talks, Munavarkhon Zakriiaevich Zokirov of Uzbekistan attempted to brush aside such fears of asymmetry in the new union, in which six out of nine anticipated republics would be “Muslim,” claiming that these republics in fact proved loyal to the Soviet cause (Verkhovnyi Sovet SSSR [Supreme Soviet of the USSR] 1991c, 19:284).

The discussion of Vladimir Il’ich Lenin’s possible burial can be seen as a manifestation of the amplified religious and nationalist particularisms. Anatolii Aleksandrovich Sobchak suggested burying Lenin, the symbol of Soviet internationalism and atheism, in accordance with the national and religious traditions of the (Russian) people just before Gorbachev closed the last Fifth USSR Congress of People’s Deputies (September 2–5, 1991). The congress itself dealt with the aftermath of the attempted coup by the Communist hardliners and marked the practical end of the USSR reform, paving the way for its dissolution on December 26, 1991 (V (vneocherednoi) S”ezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR [Fifth (Extraordinary) Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR] 1991, 19).

Conclusion

There was no consensus on what religion meant in the parliamentary debates of perestroika. During the early phase of the debates, religion as an abstract category was seen as a key foundation for a spiritual revival and for perestroika’s ultimate success. The particularistic understandings of religion, which were also present from the very beginning, proved more prominent, however, and the question which religion was to become the foundation of perestroika shifted to the foreground. The latter question connected religion to the multiple interethnic conflicts across the USSR and launched the discussions of new imperial hierarchies, which in the RSFSR could mean the domination of the Russian Orthodox Church and selected recognition of other religions.

The representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church attempted to claim the whole religious space of the USSR and, then, of the RSFSR. By making a particularistic (Orthodox Christian) understanding of religion the foundation of a new Russian ideology, they contributed to the homogeneous picture of Russian national history and culture, concealing if not denying the presence of the religious “other” (see the Introduction to this special issue). The attempts to turn Orthodox Christian particularism into a new Russian imperial universalism were reminiscent of the attempts of Russian nationalists to claim a similar space in the Russian Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, which contributed in the imperial revolution (Gerasimov 2017).

The state-centered approach to religion, which can be traced to perestroika’s overall etatism, made religion an important part of nation-building, which in the case of Russia connected Russian nationalism to Orthodox Christianity and, despite the lip service to diversity, was reflected in the explicitly Christian swearing-in of the first Russian President. The location of religion in the past also contributed to stronger particularisms as religion became an element of primordial nationalism with its idea of cultural difference rather than cultural affinity. Finally, both the etatism and the primordialism contributed to the attempted centralization of Russia’s traditional religions, four of which finally made it into public education and the army (Sablin 2018).

Acknowledgement

The research for this article was done as part of the project “ENTPAR: Entangled Parliamentarisms: Constitutional Practices in Russia, Ukraine, China and Mongolia, 1905–2005,” which received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement No 755504).

Sources

Pravda, October 7, 1990.

Izvestiia, December 7, 1960.

Izvestiia, October 1, 1980.

References

In the context of this article, the term perestroika is understood in the broad sense and refers to the whole era of economic “reconstruction,” the introduction of political openness (glasnost) and pluralism, and other reforms in the USSR.↩︎

The term empire was in fact explicitly articulated in the parliamentary debates, although in a political rather than analytical sense. Defining the RSFSR and decrying the power asymmetries in it and the USSR as whole, Murad Rasil’evich Zargishiev of Dagestan, for instance, asserted, “In my opinion, being a de jure republic, de facto it remains an empire, being, in turn, a part of another empire” (I S”ezd narodnykh deputatov RSFSR [First Congress of People’s Deputies of the RSFSR] 1992a, 1:427).↩︎

Using OCR (optical character recognition), the scanned records were made searchable. Then every located use of the word “religion” and its derivatives was analyzed. Further research could rely on the yet to be digitized records of the supreme soviets of the union and autonomous republics, including the RSFSR Supreme Soviet.↩︎

All translation by the author unless indicated otherwise.↩︎