Between Secrecy and Transparency

Conversions to Protestantism Among Iranian Refugees in Germany

Present-day scholarship on religious conversions diverts from classic Protestant paradigms of sudden conversions and instant transformations of the self. Instead, it stresses that converts make active choices that are influenced by specific contexts and historical changes. This becomes evident in an ethnographic study of one controversial aspect of the recent refugee influx in Germany: the so-called mass conversions of Iranian refugees from Shia Islam to Christianity, which have been highly publicized and criticized since the height of immigration in 2015. The analysis draws on interview data with Iranian refugee converts and their pastors in Protestant churches in North Rhine-Westphalia between October 2017 and January 2018. The study reveals the need to theorize the symbiotic connection between religious contacts, forced migration, and conversion to Christianity. It applies Rambo’s (1993) stage model of conversion and the analytical concept of secrecy (Jones 2014, Manderson et al. 2015, Simmel 1906) to demonstrate that the Iranian refugees’ conversions are shaped by contexts, crises, encounters, quests, interactions, commitments, and consequences (Rambo 1993) as they negotiate the forces of secrecy, risk, transparency, and the benefits of being a Christian. The goal of this paper is to find thematic patterns in their narratives that can be systematized and can build a foundation for further study.

Refugee crisis in Germany, conversion, Christianity, stages of conversion, Iranian refugees, thematic narrative analysis, ethnography, secrecy

Introduction

Ebrahim1 sits across from me in a small room in his new Protestant church in North Rhine-Westphalia. He is a 32-year-old refugee2 from Iran who, like most other refugees interviewed for this study, had converted to Christianity from Shia Islam in Iran and was religiously persecuted. Also like others, he explained that he practiced Christianity in secret and that a police raid of the underground house church he frequented in Teheran lead to his arrest and subsequent forced migration: “In Iran, I was praying in the church. The church is not always in one house. For example, one time it is there, tomorrow somewhere else. It is not consistent. This week one can pray, the next week not. Sometimes when the house is not safe, nobody can pray. Once I have prayed in a house and the neighbor used the telephone and the police came. Okay, you all go home, but don’t leave town. Then they called back and said I have to return to the police right away. And I left, done. Not again to the police. I didn’t wait. The lawyer said, leave immediately. If you stay, then problem. First leave, then think about a solution.”

Ebrahim’s conversion story and the stories of other Iranian refugees interviewed for this study are intimately connected to the processes of religious contacts, persecution, religious socialization, and forced migration from Iran to Germany, which is demonstrated below.

Ebrahim is one of many refugees who came to Germany during the height of the so-called refugee crisis in 2015, which gained intensity in the course of the Syrian civil war and other humanitarian and political crises. The German Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, or BAMF (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees), recorded approximately 1.1 million asylum applications in 2015 alone (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge 2016). Ensuing rapid cultural and religious contacts can be conceptualized with Pratt’s (1991) term contact zone: Middle Eastern, Iranian, North African, and German cultures, as well as multiple religions, negotiate their standings in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, translating into polarized publics. On one hand, we find adherents of a pro-immigration Willkommenskultur (welcoming culture). On the other hand, we find resistance groups with an anti-immigration, anti-Islam, and German nationalist agenda, such as the Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West (PEGIDA) (Frindte and Dietrich 2017).

Ebrahim encounters a climate of public mistrust of refugees and of skepticism of their place within German society. This climate is fashioned by media discourses in two major ways: first, refugees have been associated with the umbrella term “Muslims” and have been projected as “suspect communities” and as threats to an ascribed Christian European Culture (Müller 2018; see also Juran and Broer 2017).3 A second source of mistrust are the recent so-called mass conversions of Muslim refugees to Christianity that have been highly publicized and criticized. While reliable official counts of these conversions have not been published,4 German mainstream media and individual churches have reported a high influx. For instance, the Alpha and Omega Persian community in Hamburg was featured in the documentary Abschied vom Islam: Wenn Flüchtlinge Christen werden (Departure from Islam: When Refugees Become Christians) of the North German Broadcasting Company (NDR) for holding mass baptisms of recent Iranian refugees in public lakes and indoor public swimming pools. Another well-publicized church is the Dreieinigkeitsgemeinde der Selbständigen Evangelisch-Lutherischen Kirche (SELK) (Trinity Church of the Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church) in Berlin-Steglitz. This church has grown from 150 predominantly German congregational members before 2015 to almost 1600 predominantly Iranian members in 2017, as stated by its pastor, Gottfried Martens (personal communication, see also Ragg 2017).

German and international media coverage has been debating the authenticity of these conversions. The German magazine Der Stern asks whether or not the conversions are just a means to expedite asylum processes (Ivitis 2016) while nevertheless acknowledging that converting to another religion from Islam is not easy for refugees since they often face ostracism from families or accusations of apostasy in German refugee camps.5 One of the more critical accounts is the British The Lip TV, whose hosts claim a mutual insincerity between asylum-seekers and churches in Germany and accuse evangelicals around the world of misusing this “fraud” for their own propaganda purposes (2015). These media discourses lead to “a cultivation of the reputation for possessing secrets” (Jones 2014, 59) by reporting concealment, not necessarily a secret itself, which then gains social force (see also Taussig 1999).

In this environment, spiritual matters regarding Ebrahim’s and other Iranian refugee converts’ religion, previously reserved for the private realm, now are subject to public debate and regulated through the neoliberal concept of transparency (Manderson et al. 2015; Han 2015). The dynamics of secrecy and transparency are situated in social relations, institutions, and technologies, and demarcate the private/public divide (Manderson et al. 2015; Teft 1980). In Germany, this is evidenced by religious organizations going public about baptisms of recent refugees: for instance, the Association of Protestant Churches and the Association of Protestant Free Churches recently published new guidelines for handling baptism requests among asylum seekers and for discussing the consequences of apostasy for Muslims converting to Christianity.6 Moreover, the pastors of Protestant churches of the EKD, or Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland (Evangelical Church in Germany), who were interviewed for this study negotiate their standing given general social pressures to be transparent and feel compelled to bring the private sacrament of baptism, as well as refugees’ conversion processes in general, into the public debate. Some pastors publicly announced that they intend to make their baptism courses stricter to prevent refugees from obtaining their baptism certificates solely for asylum purposes. Others claim that they treat baptism as a type of Seelsorge (spiritual guidance) and that they perceive themselves as facilitators of a relationship between God and the converts. They argue that they, as mere humans, are not qualified to pass judgment on God’s work in refugees and refer to biblical history as evidence of God working repeatedly through migration (personal communication).

Secrecy and transparency also are means by which refugees shape their intersubjective lives within oppressive societal forces (Manderson et al. 2015). Refugees, as social persons, are the products of repeated individual and group socialization through hiding and revealing signs of their Christian conversion within various religious and political environments. In terms of secrecy, the converts learn to acquire Christian practices and rituals in secret in Iran and are concerned about hiding them from the Iranian public or even from family members. In Germany, they are pressed to be transparent and to propel their Christian identity into the open. When they apply for asylum, for instance, they are interviewed on the legitimacy of their faith by the German migration authorities. A controversial Glaubensprüfung (faith test) is administered and examines whether refugees are so spiritually moved by their new beliefs that this emotionality translates into their daily activities; they receive asylum if they can convince the interviewers that these activities would be continued in their home countries, which would then result in persecution (Franz 2017).7 The refugees’ preparation for such faith tests is extensive, and some hire lawyers to instruct them on appropriate answers, which additionally shapes their Christian selves. These pulls between secrecy and transparency are part of the converts’ reality and regulate their religious experience through technologies of social control (see Foucault 1977).

This study traces the formation of refugees’ new Christian identities through various stages (Rambo 1993) in narratives collected from interviews. These stages involve their first contacts with Christianity in Iran, the Iranian government’s censorship of Christian practices, their social exclusion in Iranian society and in refugee camps in Germany after their forced migration, and their integration into new German church communities. The study does not focus on or make claims about the “authenticity” of these conversions. Instead, it examines the correlation between refugees’ conversion to Christianity, religious contacts, and forced migration within tense religious fields (Bourdieu 1990; Dianteill 2003) in Germany and Iran. It argues that the dynamics of secrecy (Herzfeld 2009; Jones 2014; Stünkel 2017) and transparency (Manderson et al. 2015; Han 2015) are highly influential in shaping refugees’ new Christian identities. While the analysis of transparency has been controversial in the social sciences and lacks conceptual clarity (see Alloa and Thomä 2018; Han 2015, among many), cultural processes of secrecy, specifically, have gained considerable attention in anthropological and social studies for their ability to reveal the impacts of censorship, control of knowledge, and of the disclosure and concealment of identities. In its early stages since the Enlightenment, the anthropological scholarship of secrecy was largely restricted to particular bounded domains, such as secret societies, trade secrets, state secrets, or unexplored geographic regions, that rule out secrecy’s potential to influence cultural meaning (Jones 2014; see also Herdt 2003). Simmel (1906) was among the first to recognize secrecy as central to the control of knowledge within societies and paved the way for the analysis of secrecy as a form of cultural production (Herdt 2003). Both anthropology and sociology began to focus on “secrecy’s potential as a generative mechanism for constituting self, society, and perhaps most importantly, culture” (Jones 2014, 54; see also Lowry 1980; Teft 1980).

Data and Methodology

Germany has seen predominantly Iranian Muslims converting to Christianity, despite the fact that the number of Iranian refugees is relatively small compared to the number of Syrian refugees, for instance. Table 1 shows that Iranian refugees comprise less than 10% compared to the total number of Syrian refugees in 2015.

| Rank | State of Origin | 2014 | 2015 | Shift 2014/2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Syria | 122,065 | 368,400 | +201.8% |

| 2 | Afghanistan | 41,405 | 181,360 | +338.0% |

| 3 | Iraq | 21,365 | 124,905 | +484.6% |

| 4 | Cosovo | 37,890 | 72,465 | +91.3% |

| 5 | Albania | 16,950 | 67,740 | +299.6% |

| 6 | Pakistan | 22,220 | 47,840 | +115.3% |

| 7 | Eritrea | 36,945 | 34,105 | -7.7% |

| 8 | Nigeria | 20,065 | 31,165 | +55.3% |

| 9 | Serbia | 30,840 | 30,050 | -2.6% |

| 10 | Iran | 10,905 | 26,550 | +143.5% |

Many Christian sources, including pastors of the Protestant EKD in North Rhine-Westphalia, suggest that these conversions originate in Iran (personal communication, see also Thomas 2018).8 These pastors explain the conversions as the result of divine intervention in Iran in the form of Wunder (miracles) or Erweckung (awakening, revival) and of Christ appearing in the refugees’ dreams. Christian news sources argue these conversion are the result of various online international missionary organizations that have been increasing their outreach through private satellite TV stations that circumvent Iranian censorship.9 The Christian Post reports a massive rise of Christian youths, which compels Iranian religious authorities, such as the Ayatollah Alavi Boroujerdi and Makarem Shirazi, to implement strategies counteracting foreign Christian influences (Zaimov 2017). The Iranian Christian news agency Mohabat News (2017) also underlines a high rate of converted Iranian youths in spite of a reported Islamic indoctrination through families and educational systems and in spite of the serious risks involved with denouncing Shia Islam. The Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) calls the Iranian underground church the fastest growing church in the world with over a million followers and with tech-savvy young people leading the way (Thomas 2018).

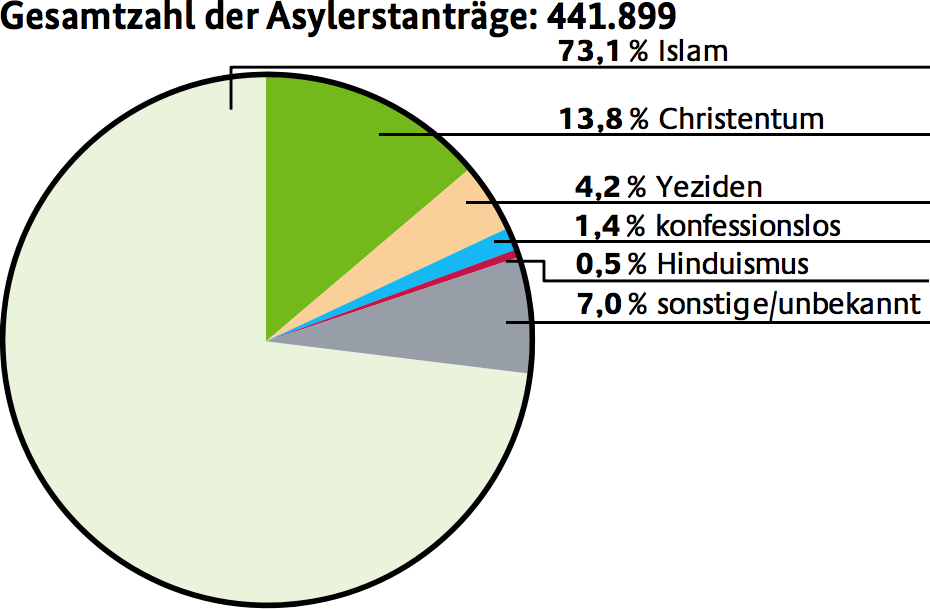

The data for this study is drawn from an ethnographic investigation that involves participant observations of and interviews with Muslim refugee converts in their EKD churches in North Rhine-Westphalia between October 2017 and January 2018. 19 of 21 interview participants are Iranian and this high number aligns with media claims that German churches predominantly host converts from Iran, as discussed above. Within Germany, North Rhine-Westphalia had the second highest number of asylum applications in 2015 (15.1%), preceded by Bavaria (15.3%) and followed by Baden-Württemberg (13%). Most asylum seekers identify with Islam (73, 1%), while Christianity and other religions follow distantly with 13.8% or less (Figure 1).

The interviews were semi-structured, posing open-ended questions and allowing for emerging themes to be explored further in follow-up questions (see Schütze 1983; Flick 2008). However, the interviewer ensured that the answers covered when, where, and how the refugees came into contact with Christianity, why they chose Christianity, as well as when, how, and why they left their original countries. As such, the interview questions elicit narratives of both conversion and forced migration as well as their symbiotic interaction. The interviews were conducted in places of the refugees’ choosing, including quiet rooms in churches, public coffee shops, and their homes. 17 interviews were conducted in German, two in English and two interviewees code-switched between English and German. The duration of the interviews ranged from 25 to 90 minutes and all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed in full.10 Table 2 shows the demographic information of all refugees interviewed.

| Name11 (Age) | Origin | Period of being Christian | Arrival in Germany | Previous religion and other affiliations (self-identified) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saad (42) | Iran | 21 years | 2015 | Zoroastrianism, Shiism |

| 2 | Milad (38) | Iran | 10 years | 2014 | Zoroastrianism, Shiism |

| 3 | Faride (34) | Iran | 4 years | 2015 | Zoroastrianism, Shiism |

| 4 | Hirbod (20) | Iran | 9 months | 2015 | Shiism, no religion |

| 5 | Sarina (34) | Iran | 1 year | 2015 | Shiism |

| 6 | Babak (35) | Iran | 6 years | 2016 | Shiism |

| 7 | Farbod (32) | Iran | 15 years | 2015 | Shiism |

| 8 | Hamid (21) | Iran | 8 years | 2016 | Shiism |

| 9 | Azar (20) | Iran | 3 years | 2015 | Shiism |

| 10 | Arash (20) | Iran | 2 years | 2016 | Shiism |

| 11 | Tabor (22) | Iran | 2 years | 2016 | Shiism |

| 12 | Ali (45) | Iran | 5 years | 2016 | Shiism |

| 13 | Reza (28) | Iran | 1 year | 2016 | Muslim, Kurdish |

| 14 | Shanita(30) | Iran | 4 years | 2015 | Shiism |

| 15 | Sharokh (35) | Iran | 7 years | 2015 | Shiism |

| 16 | Jaleh (26) | Iran | 1 year | 2016 | Shiism, Atheist |

| 17 | Ebrahim (32) | Iran | 17 years | 2015 | Shiism |

| 18 | Dalir (25) | Iran | 5 years | 2016 | Shiism |

| 19 | Soban (21) | Iran | 3 years | 2015 | Shiism |

| 20 | Aziz (38) | Iraq | 1 year | 2012 | Muslim, Yazidi |

| 21 | Hussam (28) | Iraq | 4 years | 2015 | Sunni |

The majority of converts interviewed describe their original religion as Shia Islam—the dominant religion in present-day Iran.12 Many emphasize that they were non-practicing, that they were born into this religion, and that they were unable to change it legally in Iran. The refugees’ ages range from 20 to 45 years and the periods of identifying as Christians also range widely, from 9 months to 21 years. Most interviewees came to Germany in 2015 (11) and 2016 (8), at the height of the so-called refugee crisis and of Germany’s open borders. It is also essential to point out that a majority (15 out of 19) of these Iranian refugees encountered Christianity in Iran. They describe their conversions and subsequent Christian practices as secretive and they eventually had to flee Iran after being persecuted for having left Shia Islam.13 They were being placed in one or more Auffanglager (reception camps) in Germany, where some felt compelled to continue hiding their new Christian orientations out of fear of retaliation for apostacy (see Peters and Vries 1976). All converts actively searched for new churches and eventually found Protestant church communities where they felt they could live openly as Christians.

Through the narratives that emerge from the interviews, the refugee converts ordered the flow of their experiences and made sense of events and actions in their lives (Riessman 1993, 2007). As such, the narratives must be analyzed as representations of these experiences, materialized through linguistic, cultural, and religious resources of the German society in the present environment. Narrative analysis as a methodology has been a privileged tool for researchers of personal, communal, and social identity construction (Brockmeier and Carbaugh 2001; De Fina and Georgakopoulou 2012; Eastmond 2007; Ochs and Capps 2002; Onega and Landa 2014, among many). While the narratology that emerged after the 1960s as a classical structuralist discipline was concerned with rules, deep structures, positivism, and dualism (Labov 1972; Labov and Waletzky 1967), more recent approaches are more suitable for this study since they highlight the dynamic function of narratives to explain, justify, describe, or interpret human experiences through different times, spaces, and sociocultural contexts (Bal 1997; Bruner 1987, 1990; Gómez-Estern and Benítez 2013; McAdams 2013; Stadlbauer 2013). Narrative analysis has become a heuristic tool for cultural analysis and is capable of tracing how refugees make sense of discontinuities and continuities in their conversions against the background of forced migration (see particularly Eastmond 2007; Gómez-Estern and Benítez 2013). The analysis of these types of narratives is important because they are “the only means we have of knowing something about life in times and places to which we have little other access” (Eastmond 2007, 249). As such, they are essential tools in uncovering the diversity behind over-generalized notions of “the refugee experience” (Eastmond 2007, 249).

In order to employ narrative analysis as a heuristic tool, one has to consider normative constructions of what is a story worth telling in a specific social and cultural setting (Gómez-Estern and Benítez 2013), which is partly shaped by the encounter and relationship between narrator and listener. All refugees who were asked to be interviewed readily agreed and some even expressed a desire to be transparent and to have their voices heard in light of the German public’s negative perception of refugees in general. As such, the interviews also function as vessels of outreach, which shows that the revelation of their secrets aims at sharing experiences, witnessing injustice, seeking rapport with the interviewer, and engaging in activism.

Consequently, the revelation of secrets is performative: it not only reveals what was hidden but also the politics behind it (Manderson et al. 2015). The narratives function as media of secrecy and “the secret’s mise-en-scène” (Manderson et al. 2015, S183), or the secrets’ settings, subjects, objects, temporalities, spatialites, and their mobilizing powers. As Jones (2014) aptly summarizes, “secrets are charged with social tension, surrounded by a palpable aura of risk to which ethnographers are not immune” (Jones 2014, 61). An ethnographer can become a ritual extension of that which they study (see also Taussig 1999).

Despite the refugee converts’ openness to being interviewed, their status is volatile and requires a careful evaluation of methodological, practical, ethical, and epistemological challenges of ethnography in general (see Duranti 1997; Bucholtz 2000, among many). Some participants have expressed the concern that the exposure of private information might influence their own or their families’ asylum procedures or lead to retribution for apostacy by community or family members. At the time of the interviews, most refugees experienced a state of liminality: some were awaiting their first interviews for asylum with BAMF. Some had finished their interviews and their asylum requests were pending. The asylum requests of some had been rejected, even though they cited their conversion to Christianity as a serious risk to personal harm if they were to return to Iran. Although Article 16a of the German Basic Law14 grants all persons persecuted on political grounds the right of asylum, the immigration authorities often treat these baptisms as a selbst geschaffener Nachfluchtgrund (self-created reason for fleeing after the fact, see Dienelt n.d.) and do not recognize conversion to Christianity as a determining factor in the asylum process. Most of them were either well into their German language and official integration courses at the time of the interviews or had already finished them. Only few of them were granted asylum and had moved from refugee camps to state-assisted apartments. Most of them were hoping to find work, either in their previous jobs as civil engineers, teachers, construction workers, and accountants, or to pursue vocational apprenticeships or university degrees. All of them were baptized and active members in their new churches.

In order to lessen any risks associated with this ethnography, the interviewer took the following precautions: (1) the refugees were provided a consent form that details their rights, the interviewer’s contact information and academic background, the nature and goals of the study, and how the data would be used and published; (2) they were assured that their names and any other markers of identity, such as names of small towns, would be anonymized; (3) they were asked to agree to be audio recorded but assured that the audio files would only be used for transcription purposes and stored on a private, password-protected computer and in a secure online storage; and (4) they were informed in advance that they would be asked to elaborate on their forced migration and conversion. Since these are sensitive topics that might lead to reliving personal trauma, the refugees were informed that they had the right to refuse answering any questions and to revoke their participation during or at any time after the interview, without any negative consequences.

Conversion Narrative Analysis

Conversion testimonies in this study are treated as instrumental for religious transformations and as lending weight to the validity of conversions (Rambo and Farhadian 2014). Conversion to Christianity, specifically, has relied heavily on testimonies and narratives historically, as exemplified by the continued influence of biblical conversion stories, such as that of Paul of Taurus (Acts 9) as a template for American evangelical born-again narratives (Bailey 2008), or of historical conversion accounts, such as that of Augustine’s fourth-century conversion in The Confessions (Hawkins 2014). Nevertheless, conceptualizing conversion is controversial, even within a particular religion or denomination, because of theological, cultural, and contextual variants. Helpful for the aim of this study are conceptualizations of conversion that position an individual’s religious change within a matrix of relationships, events, ideologies, or institutions and within wider political, social, cultural, and global changes, all of which are interactive and cumulative. These dynamic approaches to studying conversion have predominantly emerged in the fields of the psychology of religion (James 1902; Nock 1933; Rambo 1993; Rambo and Farhadian, Charles E. 1999, Rambo & Farhadian 1999; Rambo and Farhadian 2014); anthropology of conversion (Gooren 2010; Keane 2007; Meyer 1999, 2011); and sociology of conversion (Lofland and Stark 1965; Lofland and Skonovd 1981; Snow and Machalek 1983).

The following conversion narrative analysis can be categorized as thematic (Riessman 2007) and its goal is to find patterned responses (see Braun and Clarke 2006; Patton 2014). Importantly, thematic narrative analysis reveals local (micro) and societal or global (macro) contexts, causality, and emergent categories across various interviews, which then can be theorized (53). Rambo’s (1993) stage model of conversion serves as a guiding theory for interpreting these themes. Given that no model can explain the complete reality of conversion, this stage model is suitable to highlight the protracted conversion processes in this study. Furthermore, it is arguably one of the most comprehensive tools for conceptualizing conversions to date. The model proposes the following seven stages, which are arranged in temporal sequence but can also occur simultaneously and interactively throughout the conversion process, which makes the stages dynamic, flexible, and inclusive:

- context is the ecology of people, places, temporalities, events, experiences, and institutions that all operate on conversion. Context continues its influence throughout other conversion stages (20).

- crisis is a religious, political, cultural, or personal disorientation that can precede or follow the contact with a new religion (50). Crisis often leads to the reevaluation of basic beliefs, worldviews, and options.

- quest assumes that people seek to maximize meaning and purpose in their religious lives and to resolve inconsistencies in their relationships to the divine (56). Quest intensifies during times of crisis (56).

- encounter with a new religion happens through people, such as missionaries, or through salient features of a religion, such as objects of worship (87). Encounter reveals the levels of access to knowledge about a new religion (94).

- interaction with a new religious community teaches converts about this community’s interpretation of doctrines, lifestyles, and expectations of converts to become fully incorporated members (102).

- commitment involves observable events or rituals that demonstrate the converts’ surrender to a new religion, such as baptisms or oral conversion testimonies (135).

- consequences of conversion are multifaceted effects that occur on spiritual, sociocultural, psychological, linguistic, and affective levels of experience (142).

Context and Crisis

When applying these stages to the narratives collected from the Iranian refugee convert, it can be observed that the context and crisis stages merge together. At the beginning of the narratives, the converts recount their conversions by introducing the times, places, participants, and initial behavior which together construct an orientation (Labov 1972). The narrated times and places are their childhoods and early adulthoods, which for most is the Islamic Republic of Iran after the 1978–79 Iranian Revolution. The converts quickly express their dismay for what they deem oppressive policies by the Iranian authorities, which include the regulation of religious contacts, punishment for denouncing Shia Islam, and enforcement of public Shia practices. Sharokh (35, a university student) criticizes this lack of religious choice and systematic oppression of Christians:

Sharokh: Ich will zuerst sagen, dass Muslime haben keine Auswahl in ihrem Heimatland zum Christen zu konvertieren und Jesus kennenzulernen, weil die großen Probleme in islamischen Ländern sind immer die Regime, die Angst haben, dass die Leute zu einer anderen Religion wechseln, dass sie die andere Religion besser kennenlernen … Damals war im Iran Krieg zwischen Irak und Iran, und dann die Leute haben Angst zu sagen sie glauben nicht an Islam oder wir sind gegen den Islam, weil im Koran ist vieles geschrieben, das nicht korrekt ist. Nach 1979, kommt eine Diktatur, Islamistische, Khomeini. Dann nach dem Khomeini kam auch der Khamenei. Der ist auch verrückt und schlimmer als Khomeini. Sie sind systematik gegen Christen und unterdrücken sie alle.

“I want to say first that Muslims have no option in their homeland to convert to Christianity and to learn about Jesus, because the big problems in Islamic countries are always the regimes who are afraid that people change to a different religion, that they learn more about another religion… Back then was a war in Iran between Iraq and Iran, and the people were afraid to say that they do not believe in Islam because many things written in the Qur’an are not correct. After 1979 came a dictatorship, Islamic, Khomeini. Then after Khomeini, came Khamenei. He is also crazy and worse than Khomeini. They are systematic against Christians and oppress them all.”

Sharokh describes Iran and other Muslim majority countries as autocratic disciplinary societies of surveillance, akin to Foucault’s (1977) metaphor of the panopticon—a state machinery that negotiates the relationship between systems of social control and the power-knowledge concept. He recounts historical elements of Iranian politics and interlaces them with value judgments, suggesting to the interviewer that the regimes are afraid of people leaving Islam, that the Qur’an is fallible, and that the Ayatollahs are simply crazy. This restraining context precedes the conversions and exposes conflicting factors that repress the process of conversion (Rambo 1993).

In addition to their dislike of contemporary Iranian regimes, the refugee converts also express strong criticism of the Muslim conquest of Persia of the seventh century and of the effects of Arab culture and Islam on the ethnic, national, and religious identities of Persians. Saad (42, a teacher), for instance, identifies with an Arische Zivilisation (Aryan civilization) that he primarily defines as non-Arab, non-Islamic, and as religiously influenced by Zoroastrianism. Milad (38, a basketball coach and former high school teacher) argues that Zoroastrianism was the religion of all Aryan people, specifically Kurds, Russians, Iranians, Indians, and Europeans. He perceives positive elements of Zoroastrianism, such as light, sun, and fire, as having been eliminated by Islam but as being revived in Christianity. Milad adds that these elements were eliminated by Islam but can be found again in Christianity. He also views Christ as the reincarnation of both Musa (Moses) and Zartosht (Zoroaster). Faride (34, a housewife) directly connects Zartosht and Christ since both advocate thinking positively, in her words, and behaving in a way that is beneficial to other people. Despite being too young to remember, they also express nostalgia for the Iran governed by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi before the 1978–79 revolution. They experience an emotional state of loss, which is often found in migration stories when refugees reimagine an idealized world (Gómez-Estern and Benítez 2013). This type of nostalgia functions to establish a continued Persian heritage and identity.

The converts narrate these macro contexts as longitudinal crises that precede and shape their conversions (Rambo 1993). Setting up these contexts as oppressive allows them to challenge Iran’s political and religious norms and to justify their choice of adopting a new religion vis-à-vis the interviewer. However, conversion is not only influenced by external macro contexts; it is also guided by internal motivations and aspirations in “the more immediate world of a person’s family, friends, ethnic group, religious community, and neighborhood” (Rambo 1993, 30), as described below.

Encounter and Quest

In the subsequent stages of their conversions, the converts describe how they encountered Christianity individually. Most had repeated chance encounters with Christians that were secretive and risky and that stimulated a quest to learn more about Christianity. They mainly encountered newly-converted relatives, distant Christian friends or employers, pastors, or missionaries. Sarina (34, a house wife), Shanita (30, a governmental employee), and Ebrahim (32, a construction worker) explain that their spouses secretly converted first and that they had noticed positive changes in their spouses’ personalities, such as Freundlichkeit (friendliness), Geduld (patience), and Ruhe (quietness, peace), which made them become interested in Christian teachings. Köse and Loewenthal (2000), in their conceptualization of conversion motifs, call the incentive behind this type of conversion affectional, pointing out that personal attachments or bonds play a central role in conversions in general (102, see also Lofland and Skonovd 1981).

However, for all three converts, convincing themselves and the interviewer of the merit of converting to Christianity entails lengthy and active quests to learn about the intellectual and theological principles of their new religion. These quests involved either reading about Christian theology and practices (Ebrahim, Sarina) or comparing biblical and Qur’anic teachings (Shanita). Similarly, Soban (21, a baker) initially was attracted to his employer’s good manners and subsequently read books about Christianity. Dalir (25, a fireman) describes that he had an Azerbaijani Christian grandmother who gave him a Bible that he fervently read before being convinced of the validity of Christian teachings. Babak (35, an accountant) first encountered Christianity through a distant Armenian Christian aunt and then traveled extensively to study Christianity. He explains:

Babak: Ich war 29 Jahre lang Muslim und dann Wechsel machen. Und die Republik sagte, warum? Du musst Muslim sein. Aber ich habe in viele Länder geguckt, Russland, Dänemark, Schweden. Ich bin gehen in alle Kirchen. Vor 2 Jahren und vor 5 Jahren habe ich in anderes Land gekuckt. Was ist christlich? Was ist ein Christ? Ich habe verstanden, dass Christ ist gut. Warum bin ich Muslim? Warum Muslim? Ich habe viel gefragt in den Kirchen über Jesus. Ich kann für mich denken.

“I was a Muslim for 29 years and then made the change. And the Republic said, why? You have to be Muslim. But I looked in many countries, Russia, Denmark, Sweden. I visited all churches. Two and five years ago, I looked into another country. What is Christian? What is a Christian? I understood that Christ is good. Why am I Muslim? Why Muslim? I asked a lot of questions about Jesus in the churches. I can think for myself.”

Babak’s testimony, and that of others, aligns with Rambo’s (1993) findings that quest in conversion accounts happens when people seek to maximize meaning in life, to establish a strong connection to the divine, to find avenues of transformation, and to remove a sense of tension (166). Babak, in particular, traveled far on his quest to learn more about Christianity and interjects this story with negative value judgments of religious oppressions he experienced in Iran. The converts’ descriptions of the lengthy processes of educating themselves through Christian scriptures and practices indicates their agency, determinacy, and rationality, which might be a possible response to the interview situation.

These narrated themes also align with Köse and Loewenthal’s (2000) intellectual motif of conversion,15 which the authors describe as becoming progressively more relevant in contemporary religious transformations through increasing global and digital access to religious information and knowledge. Scholars on religion and media have long shown that digital spaces allow people to shape new religious structures, categories, boundaries, and communities (see Hoover and Coats 2015; Hoover and Clark 2002; Morgan 2013, among many). Even more, scholarship that approaches the religion-media nexus from a media-anthropological point of view emphasizes the social impact of digital media, especially in how communication media provide individuals with tools and knowledge to construct new social or religious realities that often deviate from traditional religious norms. One example in the data for this study is the converts’ use of Christian websites and apps that evade Iranian censorship and that allow them to stream Christian documentaries and interact with Christians in different countries. Especially popular are international digital missionary organizations that stream programs via Satellite TV from outside of Iran, such as Mohabat TV’s Heart4Iran Ministries and Sat 7’s Iran Alive Ministry. The latter was founded by the Iranian-born minister Hormoz Shariat in Northern California in 2001 and is well known for its 24-hour Christian programming, counseling, and call centers, through which two of the converts interviewed repeatedly interacted with other Christians. This digital ministry claims that they have reached millions of Iranians, strengthened persecuted believers, and helped plant house churches in Iran.16 As such, digital access to and repeated digital interaction with international Christian organizations shapes the converts’ Christian orientation.

In sum, the refugees’ encounters and quests can be categorized as affective, i.e. meeting and forming bonds with Christians, and as intellectual, i.e. searching for meaning after the encounters through literature, church visits, and digital access. Despite having their religious lives severely restricted in the Iranian context, the converts create, utilize, and sustain alternative participation networks that enable repeated religious encounters and, eventually, conversion.

Interaction and Commitment: in Iran

In the interaction stage, converts become part of new religious communities and learn to experience religion beyond the intellectual level (Rambo 1993). Here, commitment is often expressed through observable practices or rituals of transformations, such as baptisms, that consolidate the conversion and bear witness to the converts’ new religion, as prescribed by a specific religion’s orthodoxy and orthopraxy. While the converts interviewed for this study perceive baptism as the most authoritative ritual solidifying their new Christian identity, they were often not able to find pastors in Iran who would perform baptisms.

The converts’ narratives reveal two interaction stages with Christian communities: (1) in Iran, when they visited house churches and Armenian churches, and (2) in Germany, when they became members of Protestant church communities (the latter is discussed in Consequences below). They demonstrate a strong commitment to interacting with and belonging to a Christian community, although in Iran this interaction was short and laced with risk. Most of the interviewees regularly visited underground house churches in their neighborhoods in Iran to pray, to learn more about Christianity, and to socialize with other Christians. These house churches were held in private apartments and their locations frequently changed in order to avoid discovery. Ebrahim and Shanita also visited Armenian churches that, in addition to Assyrian churches, are tolerated church communities in Iran. Shanita explains that she was instructed not to talk in masses or participate in any church activities.

Shanita: Und dann ich war regelmäßig in der Kirche, aber Armenische Kirche. In Armenische Kirche darf ich nicht sprechen. Warum? Wenn ein Iraner oder Muslim in einer Armenischer Kirche war, das ist auch gefährlich. Das dürfen wir nicht. Das ist auch gefährlich. Und ich habe gesagt, okay, ich spreche nicht, aber ich will kommen.

“And then I was in church, regularly, but in an Armenian church. In an Armenian church, I am not allowed to speak. Why? When an Iranian or Muslim was in an Armenian church, that is also dangerous. We are not allowed to do that. That is also dangerous. And I said, okay, I don’t speak, but I want to come.”

Shanita further describes the church as heavily guarded by Iranian intelligence officers and surveilled by cameras to ward off any Muslims that seek to attend Christian masses. As such, the new converts not only risked their own well-being and freedom but became a risk factor for other Christians as well.

This type of enforced secrecy leads to encapsulation—the mechanisms of how marginalized religious communities create and maintain their religious worlds (Rambo 1993, 104). The house churches, especially, function as secret societies (Simmel 1906), where each member’s interaction depends on protecting ideas, objects, activities, or sentiments that have enough value to take a risk. The members control the distribution of information within the group and to the outside. Simmel distinguishes between two types of secret societies: those whose mere existence is secret from other members of society and those who only have parts of their workings hidden. The house churches fall into the latter category, since the Iranian authorities are aware of their presence but generally do not know who the members are or where the gatherings are held. Risk often engenders secrecy as a strategy to manage perilous social relations (Jones 2014).

This physical encapsulation is also accompanied by social, ideological, and spiritual encapsulation since the converts slowly transition into divergent patterns that render them outsiders (Rambo 1993). Social encapsulation occurs since many converts keep their conversions and subsequent Christian practices a secret from family members, either because they do not trust anyone or because they do not want to put their family at risk in the case of the police raiding their houses. These types of religious contacts, as Krech (2014) argues, challenge religious subjects to establish their identity within a religious field inwardly and outwardly and thus demarcate boundaries (64). Stünkel (2017) argues that the working power of secrecy in religious contact situations can cause in-group and out-group-distinctions and a mode of exclusion of the Other. These situations also lead to ideological and spiritual encapsulation, because the converts cultivate “a worldview and belief system that ‘inoculates’ the adherent against alternative or competitive systems of belief” (Rambo 1993, 106). While many converts describe that they continued to execute pro forma Shia Islamic rituals in order to avoid raising suspicion, such as visiting the mosque every Friday or fasting during Ramadan, they were increasingly convinced of the sacredness of their new Christian beliefs and, at the same time, of the wrongfulness of the mainstream’s beliefs.

Consequences

The consequences of the converts abandoning their Shia Islamic beliefs and practicing Christianity are discovery, persecution, and forced migration. Rambo (1993) argues that the consequences of conversion are generally complex and multifaceted, which is especially accurate in situations of forced migration. This study focuses on two types of consequences: (1) sociocultural and (2) spiritual/ideological consequences.

Sociocultural Consequences: In Iran and Germany

Sociocultural consequences of conversion highlight the converts’ lives beyond their personal religious transformation and their engagement in wider social systems, including the quality of life produced by these systems (Rambo 1993). Up to this point, the events were narrated in a consistent and sequential structure, but now there is a rupture in their story (Gómez-Estern and Benítez 2013; see also Bruner 1990): their secret identities as Christians are exposed. The converts explain that they were betrayed by friends, relatives, or neighbors, which led to their arrests, accusations of apostacy, various periods of imprisonment, corporal punishment by the Iranian police, and their forced migration. They had anticipated these consequences, but nevertheless had hoped to avert them. Arash (20, a sales person) and Hamid (32, a civil engineer), for instance, explain that they had to endure 80 lashes on the back for being part of a Christian house church and for claiming a Christian identity. Farbod (32, a construction worker) received 70 lashes after having his tattoo of a cross discovered. Most converts were forced to leave their apartments and home towns abruptly after being betrayed or after being released from prison the first time (see Ebrahim’s narrative in the introduction to this paper). Dalir recounts his wife betraying him:

Meine Frau hat das Bibelbuch zu Hause gefunden. Und hat gefragt, ist das Bibelbuch für dich? Und ich habe gesagt, ja. Und meine Frau schickt mir die Polizei und sagt, mein Mann ist Christ geworden. Und die Polizei kam, aber ich bin vorher weg.

“My wife found the Bible at home. And she asked, is that Bible for you? And I said, yes. And my wife sent the police for me and said, my husband has become a Christian. And the police came, but I was gone before.”

Many other converts also experienced severe losses as a consequence of leaving Islam and becoming Christian. Hamid sharply criticizes the Iranian police for taking away his apartment, car, job, and money as a penalty for becoming Christian. He stresses that he had a comfortable life in Iran before his new religious orientation was discovered. In all these cases, the benefits of becoming Christian outweigh risks to family relations as well as to physical and mental well-being.

Upon their arrival in Germany, the converts were assigned to refugee camps. They described staying in the camps and meeting other refugees as largely positive. However, some explained that they encountered Muslims in the camps that reinforced oppressive policies of religious intolerance. While the converts expressed a desire to openly practice their new Christian faith right away, they also realized that revealing their new orientations meant that their wellbeing and peace could be jeopardized. For some, the camps comprised microcosms of the processes of discrimination against religious minorities they experienced before, and they again felt the tensions between secrecy, transparency, and risk. Faride explains that her 6-year-old daughter was bullied in the camp by other children for not being Muslim and for not speaking Arabic. When her husband joined them in the camp, the camp supervisor moved them to a slightly more secluded area. Similarly, Jaleh (26, a metal worker) made a resolution after arriving in Germany that he would never talk about religion and politics with other refugees. He details the following incident:

Jaleh: Einmal kamen sie zu mir mit dem Messer. Meine zwei Freunde hatten ein Kreuz als Kette und eines war in Gold. Aber die Araber haben das im Streit kaputt gemacht und weggenommen. Nur weil wir Christen waren im Camp … Über zwei Sachen rede ich nie: Religion und Politik.

“Once they came to me with a knife. My two friends had a cross as a necklace, and one was in gold. But the Arabs broke it during a fight and took it away. Only because we were Christian in the camp … I don’t discuss two things: religion and politics.”

Nevertheless, all converts interviewed for this study were active members in their Protestant churches at the time of the interviews and some conducted church outreach or online missionary activities. Shanita, despite being initially afraid of other Iranians in her new church, now organizes Begegnungscafes (coffee meetings) every other week for Iranians and German church members and helps structure the Persian-language sections of Sunday’s sermons. Faride functions as a liaison between the clergy and the Persian community. She helps not only with translation, but also with the interpretation of scriptures. Both women also mentioned using various social media platforms, especially WhatsApp and Facebook, to reach out to Iranian Christians and Shia Muslims.17

Spiritual and Ideological Consequences: In German Churches

The spiritual and ideological consequences of the Iranian refugees’ conversions are narrated through new communication patterns that they acquired both in their new church communities and in the wider German society, where they also learn German and form new emotional bonds. In specific, the converts learn new systems of meaning and morality which derive from their new church communities’ interpretation of theological precepts and from their everyday experiences of living in contemporary Germany. Importantly, both of these are normative (Rambo 1993) and overlap.

When reflecting on their present Christian identities since their arrival in Germany, many converts emphasized the German word Freiheit (freedom).18 Soban explains that the best aspect of Christianity in Germany is freedom and he states, ich kann leben wie ich bin (I can live as I am). Similarly, Aziz (38, a food vendor) mentions, man hat hier Freiheit. Man hat Frieden. Und ich muss leben in Freiheit. Nicht immer Angst haben (One has freedom here. One has peace. And I must live in freedom. Not always being afraid). Reza (20, a shoemaker) describes several types of theological and social freedom which overlap in his narrative. This overlap is common in the narratives collected and captured in the excerpt below. Reza sets up multiple levels of moral evaluations through which he discusses freedom. These moral evaluations deserve closer attention and hence this excerpt is organized with line numbers to refer to each meaningful element in depth. The moral evaluations are external to the sequential narrative event flow (Labov 1972; Schiffrin 2009), but lend weight to the rationale behind conversions.

Reza:

| 1 | Bevor war ich ein Fisch in einem kleinen Aquarium. | Before, I was a fish in a small aquarium. |

| 2 | Aber jetzt, nein, ich liebe Gott. | But now, no, I love God. |

| 3 | Bevor Gott sagte, du musst das, das, das | Before, God said you have to do this, this, this. |

| 4 | Aber jetzt weiß ich, mein Gott ist groß. | But now I know my God is large. |

| 5 | Er ist freundlich. | He is friendly. |

| 6 | Ich habe keine Angst. | I have no fear. |

| 7 | Aber bevor hatte ich viel Angst. | But before I had a lot of fear. |

| 8 | Und jetzt bin ich in einem großen Meer. | And now I am in a large ocean. |

| 9 | Viele Möglichkeiten. | Many opportunities. |

| 10 | Ich kann denken. | I can think. |

| 11 | Ich kann fragen. | I can ask. |

| 12 | Ich kann lesen, lernen. | I can read, learn. |

| 13 | Und ich bin frei. | And I am free. |

Moral evaluations are often communicated through a variety of cultural and linguistic features, such as proverbs, visual representations, or metaphors (Ochs and Capps 2002). Reza frames this moral evaluation with a metaphor that symbolizes his physical and mental restriction in pursuing God in Iran and his subsequent liberation. The source domain of this metaphor—a fish that used to swim in a small aquarium (line 1) now swims in a big ocean (line 8)—establishes concrete and relatable interpretation for the more abstract target domain—Reza’s religious experience in Iran and Germany (see Lakoff 1991; Lakoff and Johnson 2003). It also helps the listener understand the gravity of his experience, as metaphors are not only devices of rhetorical embellishment but also central communicative staples in everyday life. Soban employs a similar conceptual metaphor when he states, Im Iran habe ich mich so gefühlt wie ein Vogel im Käfig. Und hier bin ich raus aus dem Käfig (In Iran, I felt like a bird in a cage. Here I am out of the cage). The evaluative and moral dimensions of these metaphors link them with the emotional and affective life as it is accounted, interpreted, and experienced through the telling (Gómez-Estern and Benítez 2013).

In lines 2–7, Reza explains the metaphor’s message of these varieties of freedom by comparing different perceptions of God. In Iran, God stood for the Iranian authorities that have the means to enforce Islamic practices and hence to speak for God. This is evidenced in line 3 when Reza states, Bevor Gott sagte, du musst das, das, das (Before, God said you have to do this, this, this). He elaborates in other parts of the interview that he was forced to uphold Islamic practices and rituals even though he did not believe in them. Many other converts also take issue with compulsory religious practices, as can be seen in Dalir’s criticism of the compulsory sadness, in his words, during the 40 days of ritual ceremonial mourning to commemorate the death of Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad. Jaleh criticizes sectarian divisions and explains that Shia and Sunni Muslims are generally friendly but that the Iranian government makes them fight each other. He denounces a celebratory day when Shia Muslims insult Umar ibn al-Khattab, an early Islamic caliph who is regarded as a leader of the ummah (Islamic community) in Sunni legal thought.

However, Reza also claims that he now knows that God is large (line 4) and he establishes the moral superiority of his contemporary beliefs. This is also expressed through emotionality when he describes his present relationship to God—a God he loves (line 2), a God who is friendly (line 5), and a God who does not need to be feared (line 6). These attributes echo present-day Protestant interpretations of an affirming God as they have emerged, for instance, in interviews with pastors of EKD churches (personal communication) and in a recent guide for EKD churches on how to handle the growing number of baptismal requests among asylum seekers, as discussed earlier.19 This guide lists biblical texts and messages that comprise the canon of the German Protestant tradition and that should be appropriated by all refugee converts. In addition to the traditional Ten Commandments (Exodus 20: 1–17) and the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6: 9–13), the guide also emphasizes passages that include attributes of a God who loves people, restores peace and hope, defies evil, provides comfort under tribulations, blesses people usually regarded as afflicted, and promises eternal life through Christ who also experienced poverty, suffering, and public hatred.20 Many of these attributes are echoed in the data. Later in the interview, Reza explains that God helped him and stood by him during his migration from Iran to Germany, when he hid in a Greek forest for 28 days with little food and water. Ebrahim also mentions that God has helped him in other difficult situations and praises immanence, redemption, and atonement in Christianity. He also experiences Frieden (peace), which is a common sentiment connected to conversions in general (Jindra 2014). Dalir states that God now fills his heart with joy since Gott ist der Erlöser, Gott ist persönlich (God is the redeemer, God is personal).

Finally, Reza narrates his religious life in Germany as laced with opportunities (line 9), freedom of thought (lines 10–12), and freedom in general (line 13). These types of freedom also align with the base domain of the second part of the metaphor: the fish is now able to swim in a big ocean (line 8). Christianity here functions as a religion of freedom, agency, and revelation—politically, theologically, and emotionally—as Reza sees prospects for a better future. Here, his moral evaluations align with local notions or standards of goodness (Ochs and Capps 2002, 45), such as the liberties of free thinking and speaking in German political thought. Ochs and Capps (2002) refer this term back to philosophers from Aristotle to MacIntyre, who “propose that moral judgments are based on standards for social roles, practices, and the good life in relation to person and community” (45).

Blending spiritual and ideological types of freedom also recalls well-documented accounts of the connection between conversion to Christianity and “modernity,” where modernity is a feature of people’s historical imagination, not an objective historical period (Keane 2007). Many scholars of conversion to Christianity, and specifically to contemporary Protestantism, demonstrate that converts construct new ways of life not only in interaction with their new Christian communities but also with the promises of neoliberal or capitalist societies (Keane 2007; Lofland and Stark 1965; Meyer 1999). This is especially true in “post-secular” societies (Habermas 2010), such as Germany, that exhibit tensions and negotiations between (de-)sacralization and (de-)secularization of social systems. While the converts are, of course, seeking to embody religious traditions, they nevertheless actively engage in complex assessments of how new religious options can confront modern challenges.

Keane (2007) explains this process by proposing a master narrative, the moral narrative of modernity, which he describes as a project of human moral and pragmatic self-transformation anchored in expectations to acquire staples of modernity: becoming emancipated human subjects who engage in self-realization, embrace freedom of thought and speech, and acquire de-fetishized perceptions of God. The modern staple of freedom of thought is frequently represented in the interviews. In addition to Reza’s narrative, it is also evident in Babak’s expert above: after he detailed his quest to visit churches in other countries to learn about Christianity, Babak ended the narrative with Ich kann für mich denken (I can think for myself). Ebrahim explains that his wife, who converted to Christianity first, has taught him to think for himself instead of blindly following Shia Islam. Jaleh criticizes what he calls the institutionalized discouragement of Iranian Shia Muslims to think for themselves. He tells a parable of a tourist in Iran visiting a cemetery and listening to someone reciting the Qur’an for a common burial ritual. When the tourist asked what it meant, nobody knew the meaning. Jaleh concludes that he feels troubled to think back to when he started to memorize and recite the Qur’an as a child without being able to translate Arabic and without knowing its meaning.

Discussion

This paper has traced stages in Iranian refugees’ formation of their new Christian identities as they were shedding enforced secrecy and governmental regulations against practicing Christianity and immersed themselves into a society and church communities that project transparency and freedom. Rambo’s (1993) stage model allows organizing the conversion narratives in the 19 interviews conducted with Iranian refugee converts. It reveals thematic patterns across narratives, which provide a timely alternative story to the overgeneralizations of the so-called mass conversions since the height of immigration in 2015. These thematic patterns involve conversion stages that the refugees deem important for narrating the development of coherent new Christian identities, starting from their first contact with Christianity in Iran, the censorship of their Christian practices, as well as their social exclusion in Iran and in the refugee camps in Germany after their forced migration, to their integration into new German church communities. The ongoing negotiations between secrecy, risk, transparency, and the benefits of being a Christian show the cumulative effects of conversion, which are particularly profound in this example of a massive historical change and global migration. The dynamic application of this model allows for the following summaries.

IN IRAN: CONTEXT 1 & CRISIS 1 Secrecy, theocratic and autocratic society, religious censorship, nostalgia, continuity with an ethnic, national, religious, and cultural Persian heritage, pro forma Shia practices, resistance. |

||

ENCOUNTER & QUEST secret chance encounters:

quest:

|

INTERACTION 1 & COMMITMENT 1 secret ritual practices and commitment

encapsulation:

|

CONSEQUENCES 1 sociocultural consequences:

|

In Iran, CONTEXT 1 and CRISIS 1 melt together and constitute the preconditions of the Iranian refugees’ conversions (see Table 3). They describe this environment as persistent throughout their lives, which left them isolated and starved for a strong connection to God. The ENCOUNTER with Christianity was mainly materialized through Christians they met and their affective connections to them. They then started an intellectual QUEST to make Christianity meaningful and morally compatible with their own value systems. Their participation in Armenian and house churches in Iran despite considerable risks (INTERACTION 1 and COMMITMENT 1) led to severe consequences (CONSEQUENCES 1): the persistent crisis (CRISIS 1) that preceded the conversions is now embodied as they are penalized and forced to leave Iran abruptly. The agency of the converts crystallizes as they actively confront their environment’s limitations, resolve their ideological conflicts, fill a void left by an unsatisfying connection to God, and find avenues of transformation (Rambo 1993; see also Rambo and Farhadian 2014).

The converts are catapulted from a climate of secrecy and oppression in Iran (CONTEXT 1) into a climate of visibility, suspicion, and compulsory transparency in Germany (CONTEXT 2, see Table 4).

IN GERMANY: CONTEXT 2 pulls towards transparency and public accountability, religious persecution in German refugee camps, integration into new church communities and into German society, influence of CONTEXT 1 |

|

INTERACTION 2 & COMMITMENT 2 becoming a member in a Protestant church

|

CONSEQUENCES 2 Spiritual and ideological consequences:

|

CONTEXT 1 and CONTEXT 2 are the most comprehensive of all the stages since they show the intensity, duration, and continuity of forces that eventually lead to redefining their perceptions of God. In their new Protestant church communities, the converts experience more intense levels of learning about their religion, beyond mere intellectual levels (INTERACTION 2). Here, they learn a new German way of life, new Christian practices, and new communication strategies through which they interpret their new selves and their relationship to God. They commit to getting baptized (COMMITMENT 2), often in a large celebratory event with other Iranian refugee converts, which they see as the consolidation of their transformation. Together, the sociocultural, spiritual, ideological consequences reveal a radically transformed life.

Further Research

While the thematic patterns established in this study reveal insights into the how the refugees’ religious conversion was influenced through various contacts to Christianity, societal pressures of secrecy and transparency, and forced migration, the following questions arise and must be investigated further in order to better understand the scope, causes, and consequences of these religious conversions:

-

What is the specific impact of the intensities, durations, and locations of various contact situations on these conversions (see Bhabha 2004; Keane 2007; Pratt 1991)? The findings in this study reveal high-impact interreligious contact situations, such as Iranian Shia Muslims meeting Christians in Iran, and low-impact, longitudinal intrareligious contact situations, such as converts integrating into German Protestantism. These various types of impacts need to be theorized.

-

How do continuity and discontinuity shape these conversions? Scholarship on conversion tends to focus on discontinuities or breaks with the past, but continuities are equally revealing and need to be studied further (see Rambo and Farhadian 2014). In this study, discontinuities are rampant since the converts relocate to Germany and convert from Shia Islam to Christianity. However, the analysis has also revealed continuities, such as the converts’ affective connection to a Persian culture and nationality and to Zoroastrianism.

-

What differences can be found in these conversion accounts? While this study concentrates on similarities between the narratives collected in the 19 interviews, it excluded a discussion of differences, by design. A focus on differences in terms of social variables, such as social class, gender, or education, would be beneficial.

-

What specific impact do digital platforms have on these conversions? An in-depth investigation into this question is pressing since the present so-called refugee crisis is often hailed as the first of this magnitude in the digital age (see Sajir and Aouragh 2019; Wimmer et al. 2017, among many).

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the Käte Hamburger Kolleg “Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe” at the Center for Religious Studies (CERES) of Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany, for sponsoring this ethnography.

References

Akcapar, Sebnem Koser. 2006. “Conversion as a Migration Strategy in a Transit Country: Iranian Shiites Becoming Christians in Turkey.” International Migration Review 40 (4): 817–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00045.x.

———. 2009. “Re-Thinking Migrants’ Networks and Social Capital: A Case Study of Iranians in Turkey.” International Migration 48 (2): 161–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00557.x.

Alloa, Emmanuel, and Dieter Thomä. 2018. Transparency, Society and Subjectivity: Critical Perspectives. Springer.

Bailey, David C. 2008. “Enacting Transformation: George W. Bush and the Pauline Conversion Narrative in ‘A Charge to Keep’.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 11 (2): 215–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41940357.

Bal, Mieke. 1997. Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. 2nd ed. Toronto ; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division.

Bhabha, Homi K. 2004. The Location of Culture. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford University Press.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brockmeier, Jens, and Donal Carbaugh. 2001. “Introduction.” In Narrative and Identity: Studies in Autobiography, Self and Culture, edited by Jens Brockmeier and Donal Carbaugh, 1–22. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Bruner, Jerome. 1987. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Revised edition. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

———. 1990. Acts of Meaning: Four Lectures on Mind and Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bucholtz, Mary. 2000. “The Politics of Transcription.” Journal of Pragmatics 32 (10): 1439–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00094-6.

Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. 2016. Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2015: Asyl, Migration und Integration. Nürnberg.

De Fina, Anna, and Alexandra Georgakopoulou. 2012. Analyzing Narrative: Discourse and Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dianteill, Erwan. 2003. “Pierre Bourdieu and the Sociology of Religion: A Central and Peripheral Concern.” Theory and Society 32 (5): 529–49. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RYSO.0000004968.91465.99.

Dienelt, Klaus. n.d. “BVerwG: Flüchtlingsanerkennung aufgrund selbst geschaffener Nachfluchtgründe.” Accessed June 8, 2018. https://www.migrationsrecht.net/nachrichten-asylrecht/1242-bverwg-fllingsanerkennung-aufgrund-selbst-geschaffener-nachfluchtgr.html.

Duranti, Alessandro. 1997. Linguistic Anthropology. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Eastmond, Marita. 2007. “Stories as Lived Experience: Narratives in Forced Migration Research.” Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2): 248–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem007.

Flick, Uwe. 2008. Managing Quality in Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York, N.Y.: Vinatage Books.

Franz, Nicolai. 2017. “Unsere Entscheidungspraxis ist differenziert.” https://www.pro-medienmagazin.de/politik/2017/10/01/unsere-entscheidungspraxis-ist-differenziert/.

Frindte, Wolfgang, and Nico Dietrich. 2017. Muslime, Flüchtlinge und Pegida : Sozialpsychologische und kommunikationswissenschaftliche Studien in Zeiten globaler Bedrohungen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Gooren, H. 2010. Religious Conversion and Disaffiliation: Tracing Patterns of Change in Faith Practices. 2010 edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gómez-Estern, Beatriz Macías, and Manuel L de la Mata Benítez. 2013. “Narratives of Migration: Emotions and the Interweaving of Personal and Cultural Identity Through Narrative.” Culture & Psychology 19 (3): 348–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13489316.

Habermas, Jürgen. 2010. “The Concept of Human Dignity and the Realistic Utopia of Human Rights.” Metaphilosophy 41 (4): 464–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9973.2010.01648.x.

Han, Byung-Chul. 2015. The Transparency Society. 1 edition. Stanford, California: Stanford Briefs.

Hawkins, Anne Hunsaker. 2014. Archetypes of Conversion: The Autobiographies of Augustine, Bunyan, and Merton. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Herdt, Gilbert. 2003. Secrecy and Cultural Reality: Utopian Ideologies of the New Guinea Men’s House. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2009. “The Performance of Secrecy: Domesticity and Privacy in Public Spaces.” Semiotica 175: 135–62.

Hoover, Stewart M., and Lynn Schofield Clark, eds. 2002. Practicing Religion in the Age of the Media. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hoover, Stewart M., and Curtis D. Coats. 2015. Does God Make the Man?: Media, Religion, and the Crisis of Masculinity. New York: NYU Press.

Ivitis, Ellen. 2016. “Wenn Flüchtlinge zu Christen werden - wahrer Glaube oder Asyltrick?” Stern.de, February. http://www.stern.de/6718850.html.

James, William. 1902. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. The Gifford Lectures on Natural Religion Delivered at Edinburgh in 1901–1902. London: Longman, Green & Co.

Jindra, Ines W. 2014. A New Model of Religious Conversion: Beyond Network Theory and Social Constructivism. Boston: Brill.

Jones, Graham M. 2014. “Secrecy.” Annual Review of Anthropology 43 (1): 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-030058.

Juran, Sabrina, and P. Niclas Broer. 2017. “A Profile of Germany’s Refugee Populations.” Population and Development Review 43 (1): 149–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12042.

Keane, Webb. 2007. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter. The Anthropology of Christianity 1. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kéri, Szabolcs, and Christina Sleiman. 2017. “Religious Conversion to Christianity in Muslim Refugees in Europe.” Archive for the Psychology of Religion 39 (3): 283–94.

Köse, Ali, and Kate Miriam Loewenthal. 2000. “Conversion Motifs Among British Converts to Islam.” The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 10 (2): 101–10. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327582IJPR1002_03.

Krech, Volkhard. 2014. “From Religious Contact to Scientific Comparision and Back: Some Methodological Considerations on Comparative Perspectives.” In The Dynamics of Transculturality: Concepts and Institutions in Motion, edited by Antje Flüchter and Jivanta Schöttli, 39–73. Springer.

Labov, William. 1972. Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Labov, William, and Joshua Waletzky. 1967. “Narrative Analysis.” In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts, edited by June Helm, 12–44. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Lakoff, George. 1991. “Metaphor and War: The Metaphor System Used to Justify War in the Gulf.” Peace Research 23 (2/3): 25–32.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 2003. Metaphors We Live By. 2nd edition. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Lofland, John, and Norman Skonovd. 1981. “Conversion Motifs.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 20 (4): 373–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386185.

Lofland, John, and Rodney Stark. 1965. “Becoming a World-Saver: A Theory of Conversion to a Deviant Perspective.” American Sociological Review 30: 862–75.

Lowry, Ritchie P. 1980. “Towards a Sociology of Secrecy and Security Systems.” In Secrecy, a Cross-Cultural Perspective, edited by Stanton K. Teft, 297–318. New York, N.Y.: Human Sciences Press.

Manderson, Lenore, Mark Davis, Chip Colwell, and Tanja Ahlin. 2015. “On Secrecy, Disclosure, the Public, and the Private in Anthropology.” Current Anthropology 56 (S12): S183–S190. https://doi.org/10.1086/683302.

McAdams, Dan P. 2013. The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live by - Revised and Expanded Edition. Expanded, Revised edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, Birgit. 1999. Translating the Devil: Religion and Modernity Among the Ewe in Ghana. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Pr.

———. 2011. “Mediation and Immediacy: Sensational Forms, Semiotic Ideologies and the Question of the Medium.” Social Anthropology 19 (1): 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2010.00137.x.

Morgan, David. 2013. “Religion and Media: A Critical Review of Recent Developments.” Critical Research on Religion 1 (3): 347–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050303213506476.

Müller, Tobias. 2018. “Constructing Cultural Borders: Depictions of Muslim Refugees in British and German Media.” Zeitschrift Für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 12 (1): 263–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-017-0361-x.

Nock, Arthur Darby. 1933. Conversion: The Old and the New in Religion from Alexander the Great to Augustine of Hippo. Oxford: Oxford University Press, http://archive.org/details/Nock1933Conversion.

Ochs, Elinor, and Lisa Capps. 2002. Living Narrative: Creating Lives in Everyday Storytelling. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Onega, Susana, and Jose Angel Garcia Landa. 2014. Narratology: An Introduction. Routledge.

Patton, Michael Quinn. 2014. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. 4 edition. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Peters, Rudolph, and De Gert J. J. Vries. 1976. “Apostocy in Islam.” Die Welt Des Islams, New Series 17 (1): 1–25.

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Profession, 33–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25595469.

Ragg, Michael. 2017. “‘Eine Erweckung, über die wir nur staunen können’.” Katholische Nachrichten, January. http://www.kath.net/news/58037.

Rambo, Lewis R. 1993. Understanding Religious Conversion. Reprint edition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rambo, Lewis Ray, and Charles E. Farhadian. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Oxford University Press.

Rambo, Lewis Ray, and Farhadian, Charles E. 1999. “Converting: Stages of Religious Change.” In Religious Conversion: Contemporary Practices and Controversies, edited by Christopher Lamb and M. Darroll Bryant, 1 edition, 22–34. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Riessman, Catherine Kohler. 1993. Narrative Analysis. SAGE.

———. 2007. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. 1 edition. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Sajir, Zakaria, and Miriyam Aouragh. 2019. “Solidarity, Social Media, and the ‘Refugee Crisis’: Engagement Beyond Affect.” International Journal of Communication 13 (0): 28. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/9999.

Schareika, Nora. 2016. “Komplexe Ursachen einer Unkultur: Was Köln mit dem Islam (nicht) zu tun hat.” N-TV, January. https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Was-Koeln-mit-dem-Islam-nicht-zu-tun-hat-article16718251.html.

Schiffrin, Deborah. 2009. “Crossing Boundaries: The Nexus of Time, Space, Person, and Place in Narrative.” Language in Society 38: 421–45.

Schütze, Fritz. 1983. “Biographieforschung und narratives Interview.” Neue Praxis 13 (3): 283–93.

Simmel, Georg. 1906. “The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies.” American Journal of Sociology 11 (4): 441–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2762562.

Snow, David A., and Richard Machalek. 1983. “The Convert as a Social Type.” Sociological Theory 1: 259–89. https://doi.org/10.2307/202053.

Stadlbauer, Susanne. 2013. “Purity, Faith Development Narratives and the Resiginification of Islamic Ritual.” Narrative Inquiry 22 (2): 348–65.

Stünkel, Knut. 2017. “Secret/Secrecy.” KHK Working Paper Series 8. https://er.ceres.rub.de/index.php/ER/concepts.

Taussig, Michael. 1999. Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. 1 edition. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

Teft, Stanton K. 1980. Secrecy, a Cross-Cultural Perspective. New York, N.Y.: Human Sciences Press, Inc.

Thomas, Geroge. 2018. “EXCLUSIVE: ‘Jesus Is Building His Church’ Inside Iran, Millions Watching Christian Satellite TV.” CBN News, January. http://www1.cbn.com/cbnnews/world/2018/january/exclusive-jesus-is-building-his-church-inside-iran-millions-watching-christian-satellite-tv.

Wimmer, Jeffrey, Cornelia Wallner, Rainer Winter, Karoline Oelsner, Cornelia Wallner, Rainer Winter, and Karoline Oelsner. 2017. “Repeat, Remediate, Resist? Digital Meme Activism in the Context of the Refugee Crisis - (Mis)Understanding Political Participation,” December. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315620596-16.

Zaimov, Stoyan. 2017. “Iranian Youths Mass Converting to Christianity Despite Islamic Indoctrination, Government’s Efforts.” Christian Post Reporter, August. https://www.christianpost.com/news/iranian-youths-mass-converting-to-christianity-despite-islamic-indoctrination-governments-efforts-195421/.